What do XPT forecasts tell us about nuclear risk?

By Forecasting Research Institute @ 2023-08-22T19:09 (+23)

This post was co-authored by the Forecasting Research Institute team. Thanks to Josh Rosenberg for managing this work, Zachary Jacobs and Molly Hickman for the underlying data analysis, Bridget Williams for fact-checking and copy-editing, and the whole FRI XPT team for all their work on this project.

The Forecasting Research Institute’s 2022 Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament[1] asked 169 forecasters to predict various outcomes related to existential and catastrophic risk, including predictions of nuclear catastrophic risk and nuclear extinction risk. We also asked about a shorter-term, smaller-scale outcome—use of a nuclear weapon causing the death of more than 1,000 people by 2024 or 2030. And we asked about shorter-term indicators of nuclear proliferation and predictions of which country will most likely first use a nuclear weapon against another nuclear power or its ally by 2030.

Although the world now has almost 80 years of experience with nuclear weapons, major disagreements and sources of uncertainty around nuclear risk persist. Uncertainty about the effects of nuclear winter was a major driver of disagreement about nuclear extinction risk. XPT forecasters were also uncertain about how to formulate base rates in the case of such an infrequent event.

This post will present the XPT’s numerical forecasts on nuclear catastrophic and extinction risk and describe the major arguments XPT forecasters used, as well as outlining sources of disagreement and uncertainty. Then, this post will present XPT forecasts on shorter-term indicators of nuclear proliferation.

Key nuclear risk findings

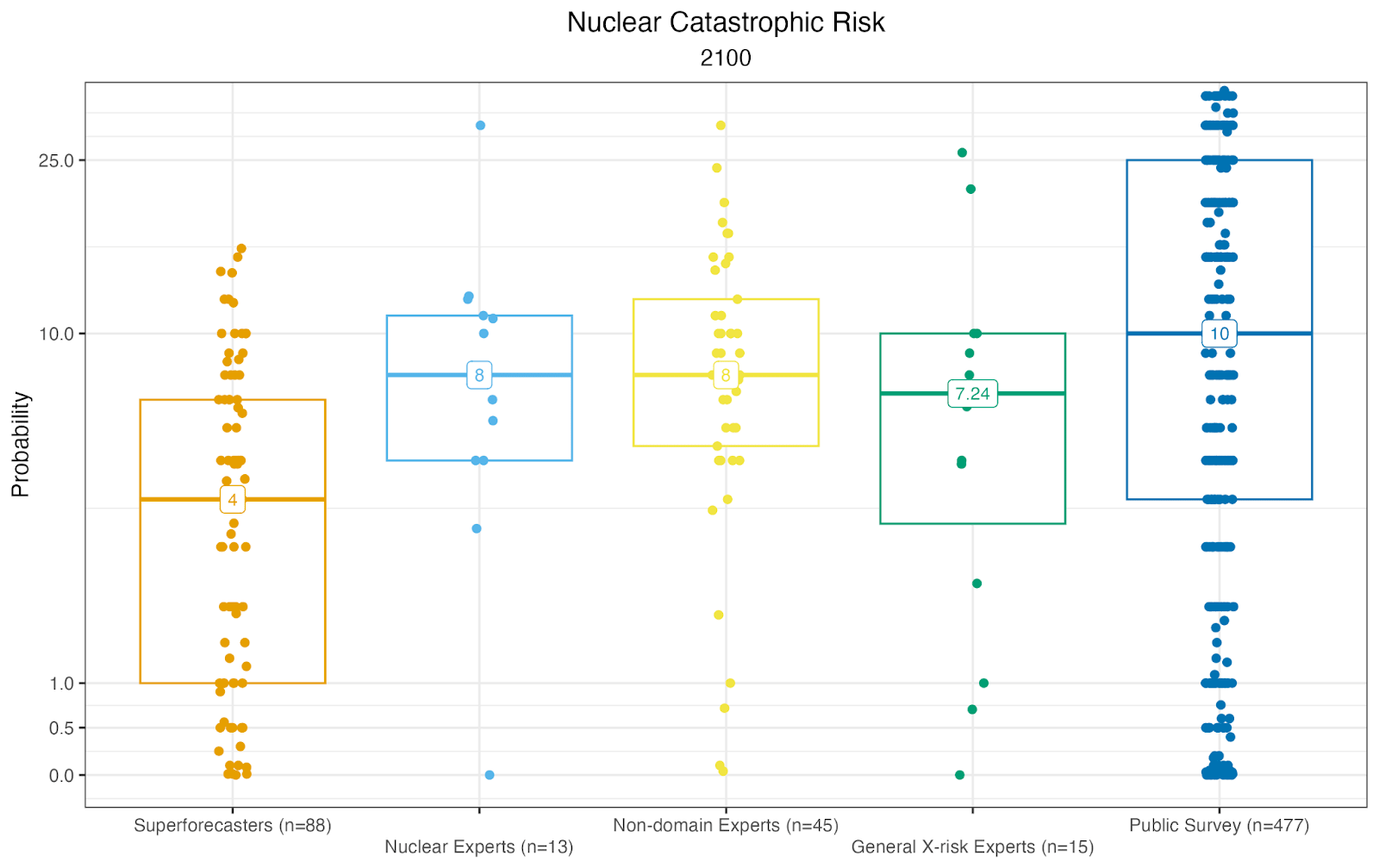

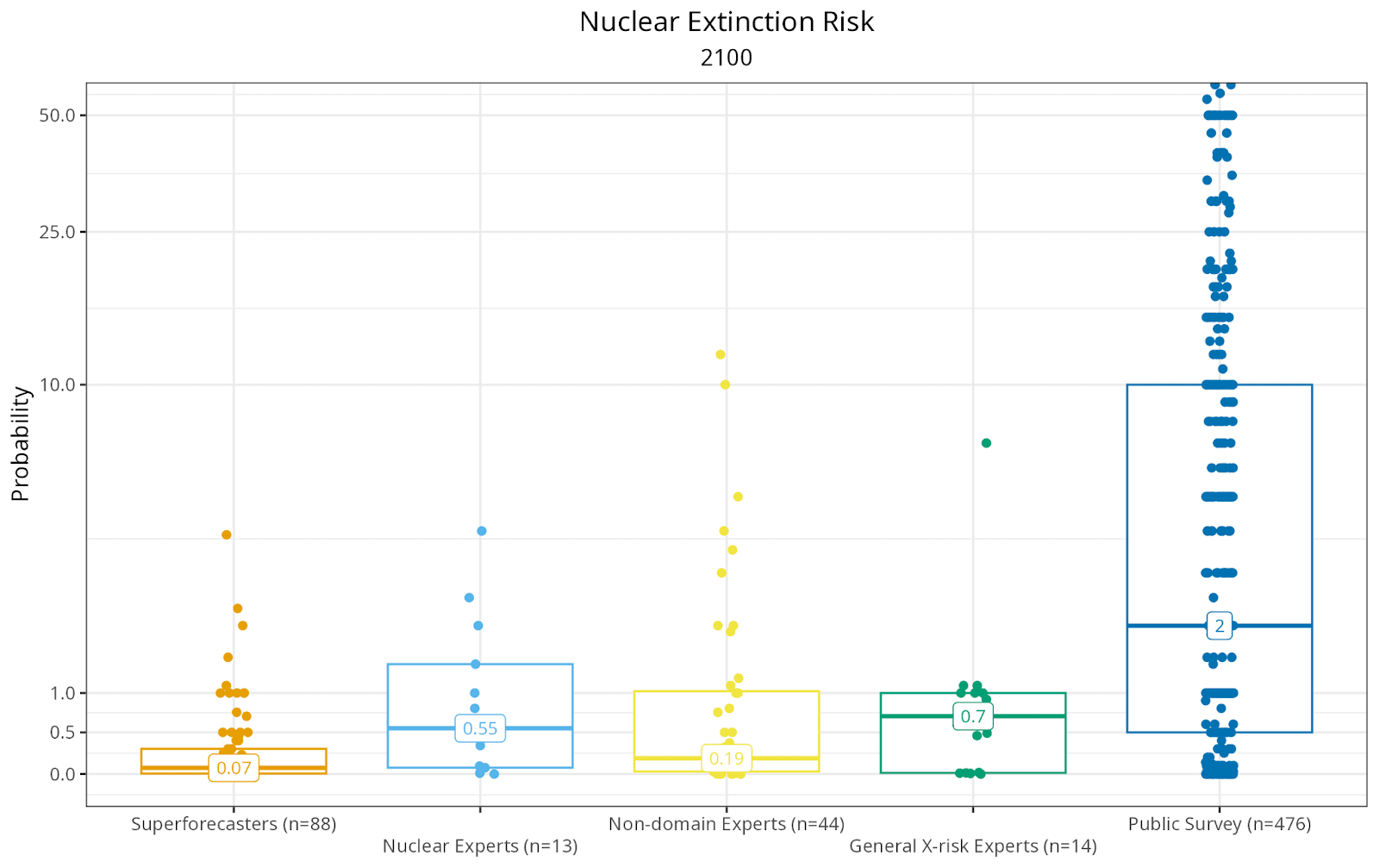

By 2100, superforecasters predicted a median 4% chance of a catastrophic outcome due to nuclear weapons, while domain experts predicted a median 8% chance. The equivalent numbers for extinction risk by 2100 were 0.074% (superforecasters) and 0.55% (domain experts).

These results are consistent with the broader XPT finding that superforecasters saw chances of both catastrophe and extinction as considerably lower than experts did. However, experts and superforecasters disagreed more about extinction risk—with extinction risk predictions nearly an order of magnitude apart—than on catastrophic risk. This could suggest that the two groups disagreed more about the effects of nuclear winter than about the chance of nuclear conflict.

On shorter-term questions, superforecasters had higher predictions on questions measuring the number of nuclear weapons in military stockpiles and the number of nuclear powers, while experts made higher predictions on questions measuring the risk of use of nuclear weapons. In other words, superforecasters expected more proliferation and less nuclear conflict risk, and experts expected less proliferation and more nuclear conflict risk. These disagreements, however, were less marked than those on nuclear extinction risk, and our domain expert sample size was small for shorter-term nuclear risk questions.

Despite these disagreements, we observed less overall disagreement about nuclear risks compared to AI risk.

Forecasts of nuclear catastrophic and extinction risk

We asked forecasters about “incidents involving nuclear weapons” and “use of a nuclear weapon.”[2] The XPT did not ask about some nuclear risks that our experts did not view as plausibly catastrophic or existential.[3]

- Nuclear Catastrophic Risk:

- What is the probability that one or more incidents involving nuclear weapons will be the cause of death, within a 5-year period, for more than 10% of humans alive at the beginning of that period…

- By the end of 2030?

- By the end of 2050?

- By the end of 2100?

- What is the probability that one or more incidents involving nuclear weapons will be the cause of death, within a 5-year period, for more than 10% of humans alive at the beginning of that period…

- Nuclear Extinction Risk:

- What is the probability that one or more incidents involving nuclear weapons will cause human extinction or reduce the global population below 5,000…

- By the end of 2030?

- By the end of 2050?

- By the end of 2100?

- What is the probability that one or more incidents involving nuclear weapons will cause human extinction or reduce the global population below 5,000…

- Nuclear Weapon Use

- What is the probability that the use of a nuclear weapon (in a single event) will cause the death of more than 1,000 people…

- By the end of 2024?

- By the end of 2030?

- What is the probability that the use of a nuclear weapon (in a single event) will cause the death of more than 1,000 people…

Group median forecasts

In the table below, we present forecasts from the following groups:

- Superforecasters: median forecast across superforecasters in the XPT.

- Domain experts: median forecasts across all nuclear experts in the XPT.

- All experts: median forecasts across all experts, including nuclear experts, general x-risk experts, and other experts in the XPT.

- Public survey: a survey of college graduates that we conducted in parallel to the XPT.

The table represents group median forecasts from the final stage of the tournament, after forecasters had the opportunity to share their earlier forecasts with each other, discuss, and try to persuade each other. (This does not apply to the public survey.) See our discussion of aggregation choices (pp. 20–22) for why we focus on medians. Please note that the time periods we asked about differ for the third question on nuclear weapon use.

| Question | Forecasters | N | 2030 | 2050 | 2100 |

Nuclear Catastrophic Risk (>10% of humans die within 5 years) | Superforecasters | 88 | 0.5% | 1.83% | 4% |

| Domain experts | 13 | 1% | 3.4% | 8% | |

| Non-domain experts | 45 | 1.4% | 4% | 8% | |

| General x-risk experts | 15 | 1% | 3.08% | 7.24% | |

| Public survey | 478 | 4% | 6% | 10% | |

Nuclear Extinction Risk (human population <5,000) | Superforecasters | 88 | 0.001% | 0.01% | 0.074% |

| Domain experts | 13 | 0.02% | 0.12% | 0.55% | |

| Non-domain experts | 44 | 0.01% | 0.071% | 0.19% | |

| General x-risk experts | 14 | 0.03% | 0.17% | 0.7% | |

| Public survey | 478 | 1% | 1% | 2% | |

| Question | Forecasters | N | 2024 | 2030 | |

Nuclear Weapon Use (causing the death of more than 1,000 people in a single event) | Superforecasters | 37 | 1.5% | 4% | |

| Domain experts | 4 | 2% | 4.5% | ||

| Non-domain experts | 12 | 2.1% | 6% | ||

| General x-risk experts | 5 | 3.3% | 9% | ||

| Public survey | 480 | 2% | 7% | ||

Box plots show the 25–75th percentile range (boxes) and the median (labeled) for each group. Within each group, points are jittered slightly horizontally to show density, but this jittering has no empirical purpose.

Box plots show the 25–75th percentile range (boxes) and the median (labeled) for each group. Within each group, points are jittered slightly horizontally to show density, but this jittering has no empirical purpose.

Comparison with previous nuclear extinction risk predictions

Although each forecast listed below was of a slightly different outcome, the XPT forecasters’ predictions of nuclear extinction risk were within the range established by previous forecasts of human extinction or other extinction risks caused by nuclear war over roughly the next 100 years.

| Group | Outcome | Forecast |

| Aird 2021 | Extrapolated median estimate of contribution of nuclear risk to total existential risk by 2100 | 1.58% |

| Sandberg & Bostrom 2008 | Human extinction risk as a result of all nuclear wars before 2100 | 1% |

| XPT domain experts (2022) | Nuclear extinction risk by 2100 | 0.55% |

| Ord 2020 | Existential catastrophe via nuclear war by 2120 | 0.1% |

| XPT superforecasters (2022) | Nuclear extinction risk by 2100 | 0.074% |

| Pamlin and Armstrong 2015 | Infinite impact by 2115 | 0.005% |

The arguments made by XPT forecasters

XPT forecasters were grouped into teams. Each team was asked to write up a “rationale” or “team wiki” summarizing the main arguments made during team discussions about forecasts. Although each XPT forecaster made their own individual forecast, part of our intention in designing the tournament this way was to encourage forecasters to think through the questions, share facts and arguments with each other, and perhaps convince each other to change their forecasts. (For FRI’s thoughts on persuasion and convergence, see the discussion beginning p. 38 of the XPT Report.)

FRI staff combed through each team’s rationales to identify what seemed to be the most frequent and most influential arguments, and those that seemed to drive disagreements between those with higher or lower risk forecasts. A limitation of our data is that XPT forecasters contributed to their teams’ written rationales at varying frequencies, and the arguments legible in written rationales may not be perfectly representative of what forecasters were thinking. In other words, arguments or facts that influenced XPT forecasters’ predictions, but were not written down, were not captured in rationales and therefore are not shown here.

The arguments presented here (and at greater length in Appendix 7 of the XPT Report) do not depict a consensus, either among all XPT forecasters or among members of each team. Quotations presented here should be interpreted with that in mind.

The major differentiating arguments around nuclear catastrophic and extinction risk centered around the following questions:

- What is the appropriate base rate for nuclear weapons use?

- How should nuclear near misses affect predictions?

- What is the likelihood and expected severity of nuclear winter?

Base rates

In contrast to AI risk, the world has almost 80 years of experience with nuclear weapons. Fortunately, the use of nuclear weapons in war has been rare. This complicates the common forecasting strategy of starting with an extrapolation from the base rate of an event (“reference class forecasting”).

What is the base rate for nuclear catastrophe? The most common answer given by XPT forecasters was zero, because the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings were not “catastrophic” as defined in our narrow, technical sense.[4] Some forecasters, however, viewed the appropriate reference class as “hostile uses of nuclear weapons,” in which case the base rate would be one or two events in 77 years (depending upon whether one groups the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings together). Some appeared to view World War II as such an exceptional event in human history that it can be disregarded as an outlier, so that the reference class would be “hostile uses of nuclear weapons when there is a not a world war,” or zero.[5]

One team noted that:

"Using different base rates and base cases results in probability estimates that differ by an order of magnitude, or even more."

Among forecasters who viewed the base rate as zero, there was no consensus on how to predict the likelihood of an event that has never occurred. Some forecasters used the rule of three or another statistical method; others did not describe any specific estimation technique.

In addition to (or instead of) arriving at a base rate, some forecasters considered specific, imaginable nuclear conflict scenarios.[6] The most commonly mentioned scenario was Russian use of nuclear weapons in response to a defeat in Ukraine or a perceived existential threat to Vladimir Putin’s regime. Some argued that we are in an unusually dangerous and volatile time due to the Russia/Ukraine conflict and tensions between China and the U.S.; others responded with claims of recency bias. As one team noted:

"There were essentially two camps as to whether the probability should be evenly spread across time, or if we are in an unusually volatile and risky time before the end of 2024."

Nuclear near misses

Many XPT forecasters mentioned nuclear “near misses” or “close calls” involving false alarms or incidents such as the Cuban missile crisis in which nuclear conflict between major powers was only narrowly avoided. One team wrote that those with higher forecasts “tended to assign more weight to the near misses of the cold war, and the behavioral failings of leaders leading up to such close calls.”[7]

Some forecasters attempted to arrive at a prediction by cataloging the number of near misses involved and assigning a probability that each of these near misses would end in nuclear conflict. Assessing which incidents qualify as near misses, and how risky the average near miss is, however, requires a number of assumptions and judgments, each of which is another potential error. Forecasters also noted that some near misses may be classified. Some teams noted the subjectivity introduced by considering near misses:

"When forecasting a question in which the base rate is zero but there are a lot of 'near-misses' then making adjustments is going to end up being very subjective."

Doubts over nuclear winter

It’s hard to kill more than 10% of humans. Many forecasters expressed the view that a catastrophic outcome would require either the use of a large number of nuclear weapons directed at centers of population, or a severe nuclear winter. For some forecasters, this ruled out the possibility of a nuclear catastrophe due to terrorist use of nuclear weapons because they believed terrorists could not plausibly acquire hundreds of nuclear weapons.[8] Even for our smaller-scale question of a nuclear weapon causing the death of more than 1,000 people by 2024 or 2030, some forecasters believed that terrorist groups (or other non-state actors) could not plausibly acquire a nuclear weapon, or the capacity to use one, without state assistance.

The difficulty of killing a large percentage of the human population applies even more strongly to nuclear extinction risk. For extinction risk in particular, forecasters noted that a great-power nuclear conflict would likely target the Northern Hemisphere more than the Southern, and that some humans live in remote areas, such as the Arctic tundra or isolated Pacific islands, that would not be likely targets during a nuclear conflict.

Models of nuclear-detonation-induced climate change or “nuclear winter” remain fortunately untested. Nuclear winter models may have flaws in the model—how well can atmospheric soot injection from volcanic eruptions serve as a proxy for soot injections from nuclear detonations?—and the results of the model depend on modelers' assumptions. (The number, type, location, and seasonal timing of nuclear detonations all affect the results of a blast.)

Forecasters also noted that some writing about nuclear winter may be intended more as anti-proliferation advocacy than as attempts to arrive at truthful predictions:

"Most research on nuclear winter does indeed seem to be by people who have campaigned for arms control…[but] it's hard to tell which direction the causation between scary nuclear winter models and campaigning for arms control goes."

Disagreement about the accuracy of nuclear winter models was a significant driver of disagreement about nuclear catastrophic and extinction risk. Some forecasters believed that even a small-scale nuclear exchange, such as one between India and Pakistan, could result in catastrophic nuclear winter; others doubted whether nuclear winter would occur even after a global nuclear conflict. As one team noted:

"How bad a nuclear [winter] would be is both very unclear and very important to answering the question at hand."

Additional sources of nuclear risk uncertainty

XPT forecasters described the following additional sources of uncertainty around nuclear risk:

- To what extent would military decisionmakers target dense centers of civilian population, as opposed to military targets?

- How likely in general is “hot” conflict between great powers?

- How well could humans adapt to nuclear winter?

- How would transformative AI affect nuclear risk?

- See this blog post for more information on how XPT forecasts of nuclear risk compared to AI risk.

- How much nuclear proliferation will occur between now and 2050 or 2100? (See table below for XPT predictions on proliferation.)

- What constraints exist on a single leader’s ability to launch nuclear weapons for irrational or short-sighted reasons?

- How powerful is the “nuclear taboo” and has that taboo been undermined over time?

Although some of these questions are more tractable than others, we expect that addressing some of these sources of uncertainty could enhance the accuracy of nuclear risk predictions.

Forecasts of other indicators of nuclear risk

In addition to larger-scale questions about nuclear extinction and catastrophic risk, we also asked about two shorter-term indicators of nuclear proliferation, i.e., the number of nuclear powers and total number of nuclear warheads. We also asked about which of a list of countries would be the first to use a nuclear weapon against another nuclear power or an ally of a nuclear power—a scenario that could lead to large-scale nuclear conflict.

For more information on these forecasts, the arguments presented in XPT forecasters’ rationales, and the sources of agreement, disagreement, and uncertainty, see pages 530 to 570 of the XPT Report.

- Total Nuclear Warheads

- How many total nuclear warheads will be in military inventories globally…

- By the end of 2024?

- By the end of 2030?

- By the end of 2040?

- How many total nuclear warheads will be in military inventories globally…

- Countries with Nuclear Warheads

- How many countries will be estimated to have at least one nuclear warhead…

- By the end of 2024?

- By the end of 2030?

- By the end of 2050?

- How many countries will be estimated to have at least one nuclear warhead…

| Question | Forecasters | N | 2024 | 2030 | 2040 |

Total Nuclear Warheads[9]

| Superforecasters | 31 | 12,700 | 12,900 | 13,500 |

| Domain experts | 1 | 9949 | 10,390 | 11,990 | |

| Non-domain experts | 10 | 12,160 | 12,084.5 | 12,952.5 | |

| General x-risk experts | 5 | 12,500 | 11,500 | 10,200 | |

| Question | Forecasters | N | 2024 | 2030 | 2050 |

Countries with Nuclear Warheads[10]

| Superforecasters | 36 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Domain experts | 3 | 9 | 10 | 10 | |

| Non-domain experts | 13 | 9 | 9 | 11 | |

| General x-risk experts | 4 | 9 | 9.83 | 12 | |

| Public survey | 480 | 9 | 10 | 12 |

Country-by-Country Nuclear Risk[11]

- What is the probability that each actor in the list below will be the first to use a nuclear weapon on the territory or against the military forces of (A) a nuclear-armed adversary or (B) a treaty ally of a nuclear-armed adversary by 2030?

- China

- France

- India

- Israel

- North Korea

- Pakistan

- Russia

- The United Kingdom

- The United States

- Other actor (state)

- Other actor (non-state)

- This will not occur

| Superforecasters (N = 33) | Domain Experts (N = 4-5) | Non-domain experts (N = 10) | General x-risk experts (N = 3) | |

| China | 0.15% | 0.2% | 0.27% | 0.78% |

| France | 0.001% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0% |

| India | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.15% | 0.065% |

| Israel | 0.1% | 0.043% | 0.1% | 0.044% |

| North Korea | 0.35% | 0.89% | 0.75% | 0.2% |

| Pakistan | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.25% | 0.092% |

| Russia | 1% | 1.87% | 2.13% | 3.8% |

| The United Kingdom | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.1% |

| The United States | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.76% | 0.6% |

| Other actor (state) | 0.05% | 0.01% | 0.1% | 0% |

| Other actor (non-state) | 0.02% | 0.000005% | 0.069% | 0.01% |

| This will not occur | 97.3% | 93.39% | 93.87% | 95.2% |

- ^

The XPT was held from June through October 2022 and included 89 superforecasters and 80 experts in various fields. Forecasters moved through a four-stage deliberative process that was designed to incentivize them not only to make accurate predictions but also to provide persuasive rationales that boosted the predictive accuracy of others’ forecasts. Forecasters stopped updating their forecasts on 31st October 2022, and are not currently updating on an ongoing basis. FRI plans to run future iterations of the tournament, and open up the questions more broadly for other forecasters. You can see the overall results of the XPT here.

- ^

Avoiding the more colloquial term “nuclear war” was an intentional choice, which allowed us to avoid definitional questions about which intentional uses of nuclear weapons constitute wars as opposed to non-war armed conflicts. For example, our forecasts were meant to cover use of nuclear weapons by terrorist groups as well as by states.

- ^

For example, the XPT did not ask forecasters to consider nuclear power plant or fuel facility accidents, dirty bombs, nuclear weapons testing, or accidental detonation of a nuclear weapon. (Accidental detonation, however, is distinguishable from intentional detonation in response to a false alarm, as in the 1983 Petrov incident.)

- ^

For further detail on this point, see our summary of forecasts on nuclear catastrophic risk. Quotes given are taken from XPT team rationales.

- ^

For further detail on this point, see our summary of forecasts on nuclear weapons use.

- ^

For further detail on this point, see our summary of forecasts on nuclear weapons use.

- ^

For further detail on this point, see our summaries of forecasts on nuclear weapons use and on nuclear catastrophic risk.

- ^

For further detail on this point, see our summaries of forecasts on nuclear weapons use and on nuclear catastrophic risk.

- ^

See the summary of forecasts on total nuclear warheads for further detail.

- ^

See the summary of forecasts on countries with nuclear warheads for further detail.

- ^

See the summary of forecasts on country-by-country nuclear risk for further detail.