Differential progress / intellectual progress / technological development

By MichaelA🔸 @ 2020-04-24T14:08 (+47)

This post was written for Convergence Analysis.

In 2002, Nick Bostrom introduced the concept of differential technological development. This concept is highly relevant to many efforts to do good in the world (particularly, but not only, from the perspective of reducing existential risks). Other writers have generalised Bostrom’s concept, using the terms “differential intellectual progress” or just “differential progress”. I think these generalisations are actually even more useful.

I’m thus glad to see that many (aspiring) effective altruists and rationalists seem to know about and refer to these concepts. However, it also seems that people referring to these concepts often don’t clearly define/explain them, and, in particular, don’t clarify how they differ from and relate to each other.

Thus, this post seeks to summarise and clarify how people use these terms, and to outline how I see them as fitting together. The only (potentially somewhat) original analysis is in the final section; the other parts of this post present no new ideas of my own.

Differential technological development

In his 2002 paper on existential risks, Bostrom writes:

If a feasible technology has large commercial potential, it is probably impossible to prevent it from being developed. At least in today’s world, with lots of autonomous powers and relatively limited surveillance, and at least with technologies that do not rely on rare materials or large manufacturing plants, it would be exceedingly difficult to make a ban 100% watertight. [...]

What we do have the power to affect (to what extent depends on how we define “we”) is the rate of development of various technologies and potentially the sequence in which feasible technologies are developed and implemented. Our focus should be on what I want to call differential technological development: trying to retard the implementation of dangerous technologies and accelerate implementation of beneficial technologies, especially those that ameliorate the hazards posed by other technologies. [...] In the case of biotechnology, we should seek to promote research into vaccines, anti-bacterial and anti-viral drugs, protective gear, sensors and diagnostics, and to delay as much as possible the development (and proliferation) of biological warfare agents and their vectors. [bolding added]

Of course, in reality, it’ll often be unclear in advance whether a technology will be more dangerous or more beneficial. This uncertainty can occur for a wide variety of reasons, including the fact that how dangerous a given technology is may later change due to the development of other technologies (see here and here for related ideas), and that many technologies are dual-use.

Note that technology is sometimes defined relatively narrowly (e.g., “the use of science in industry, engineering, etc., to invent useful things or to solve problems”), and sometimes relatively broadly (e.g., “means to fulfill a human purpose”). Both Bostrom and other writers on differential technological development seem to use a narrow definition of technology. This excludes things such as philosophical insights or shifts in political institutions; as discussed below, I would argue that those sorts of changes fit instead within the broader categories of differential intellectual progress or differential progress.

Differential intellectual progress

Other writers later introduced generalisations of Bostrom’s concept, applying the same idea to more than just technological developments (narrowly defined). For example, Muehlhauser and Salamon quote Bostrom’s above recommendation, and then write:

But good outcomes from intelligence explosion [basically, a rapid advancement of AI to superintelligence] appear to depend not only on differential technological development but also, for example, on solving certain kinds of problems in decision theory and value theory before the first creation of AI (Muehlhauser 2011). Thus, we recommend a course of differential intellectual progress, which includes differential technological development as a special case.

Differential intellectual progress consists in prioritizing risk-reducing intellectual progress over risk-increasing intellectual progress. As applied to AI risks in particular, a plan of differential intellectual progress would recommend that our progress on the scientific, philosophical, and technological problems of AI safety outpace our progress on the problems of AI capability such that we develop safe superhuman AIs before we develop (arbitrary) superhuman AIs. [bolding added]

Tomasik also takes up the term “differential intellectual progress”, and tentatively suggests, based on that principle, actions such as speeding up the advancement of social sciences and cosmopolitanism relative to the advancement of technology. (Note that Tomasik is seeing technology as a whole as relatively risk-increasing [on average and with caveats], which is something that the original concept of “differential technological development” couldn’t have captured.) Tomasik provides in this context the following quote from Isaac Asimov:

The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.

Note that, while the term “differential intellectual progress” was introduced in relation to AI alignment, and is often discussed in that context, it can be about increases and decreases in risks more broadly, not just those from AI.

Also note that we’re using “progress” here as a neutral descriptor, referring essentially to relatively lasting changes that could be either good or bad; the positive connotations that the term often has should be set aside. "Differential intellectual development" might therefore have been a less misleading term, given that it's somewhat easier to interpret "development" as being neutral rather than necessarily positive.[1] I will continue to use the established terms "differential intellectual progress" and "differential progress", but when defining and explaining them I'll say "development" rather than "progress".

Differential progress (and tying it all together)

Some writers have also used the seemingly even broader term differential progress (e.g., here and here). I haven’t actually seen anyone make explicit what slightly different concept this term is meant to point to, or whether it’s simply meant as an abbreviation that’s interchangeable with “differential intellectual progress”.[2]

But personally, I think that a useful distinction can be made, and I propose that we define differential progress as “prioritizing risk-reducing developments over risk-increasing developments”. This definition merely removes the word “intellectual” (in two places) from Muehlhauser and Salamon’s above-quoted definition of differential intellectual progress, and replaces "progress" with "developments" (which I would personally also do in defining their original concept, to avoid what I see as misleading connotations).

Thus, I propose we think of “differential progress” as a broad category, which includes differential intellectual progress as a subset, but also includes advancing types of risk-reducing developments that aren’t naturally considered as intellectual. These other types of risk-reducing developments might (perhaps) include the spread of democracy, cosmopolitanism, pacifism, emotional stability, happiness, or economic growth. (I don’t know if any of these are actually risk-reducing; I’m merely offering what seem to be plausible examples, to help illustrate the concept.)

Intellectual developments were obviously a necessary prerequisite for some of those forms of development. For example, someone had to come up with the idea of democracy in the first place. And intellectual developments could help advance some of those forms of development. For example, more people learning about democracy might increase its spread, and the development of better psychotherapy might aid in spreading emotional stability and happiness.

But these forms of development do not necessarily depend on further intellectual developments. For example, democracy has now already been invented, and there may be places where it’s already widely known about, but just not implemented. The uptake of democracy in such places may be better thought of as something like “political developments” or “activism-induced developments”, rather than as “intellectual developments”.

Differential progress also includes slowing risk-increasing developments. Such risk-increasing developments can include intellectual progress. But they can also include types of development that (again) aren’t naturally considered as intellectual, such as (perhaps) nationalism, egoism, or economic growth. Development along these dimensions could be slowed by intellectual means, but could also (perhaps) be slowed by things like trying to make certain norms or ideologies less prominent or visible, or being less economically productive yourself.[3]

(In fact, because Tomasik’s essay discusses many such types of developments, I think (with respect) that his essay would be better thought of as being about “differential progress”, rather than as being about “differential intellectual progress”.)

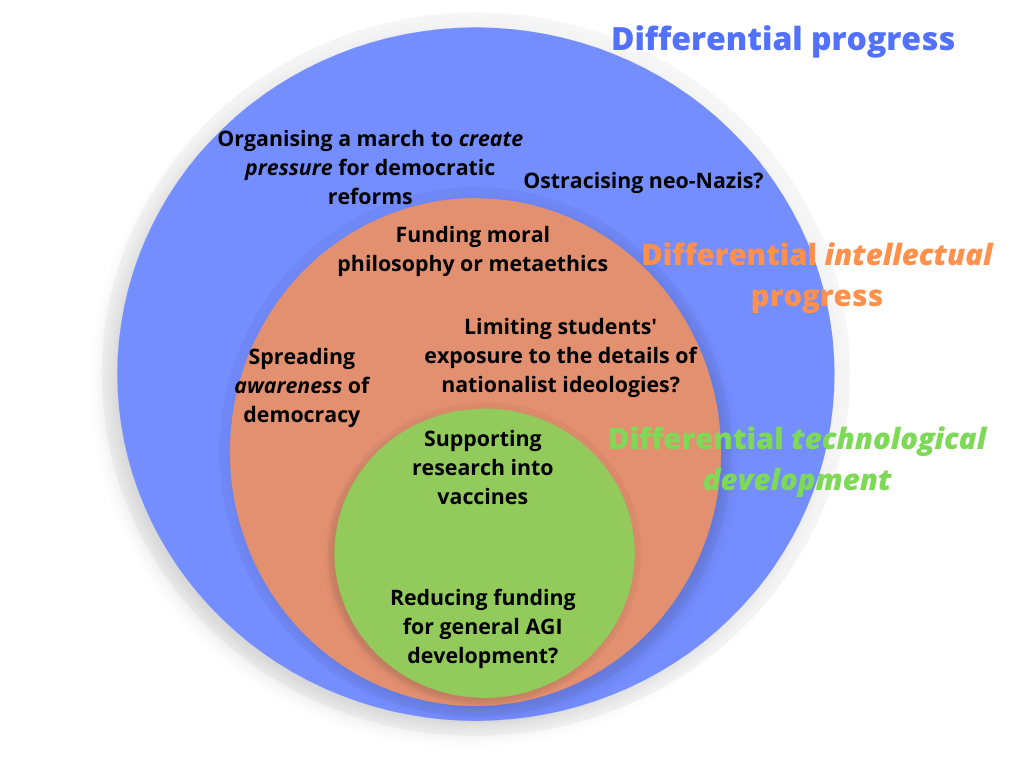

How does differential technological development fit into this picture? It’s a subset of differential intellectual progress, which (I propose) should itself be a subset of differential progress as a whole.[4] We can thus represent all three concepts in a Venn diagram (along with some possible examples of activities that these principles might suggest one should do):

I’d also like to re-emphasise that my aim here is to illustrate the concepts, not make claims about what specific actions these concepts suggest one should take. But one quick, tentative claim is that, when possible, it may often be preferable to focus on advancing risk-reducing developments, rather than on actively slowing risk-increasing developments via methods like trying to shut things down, remove funding, or restrict knowledge. One reason is that people generally like technological development, funding, access to knowledge, etc., so actively limiting such things may result in a lot more pushback than just advancing some beneficial thing would.[5] (This possibility of pushback means my examples for slowing risk-increasing developments are especially uncertain.)

Relationship to all "good actions"

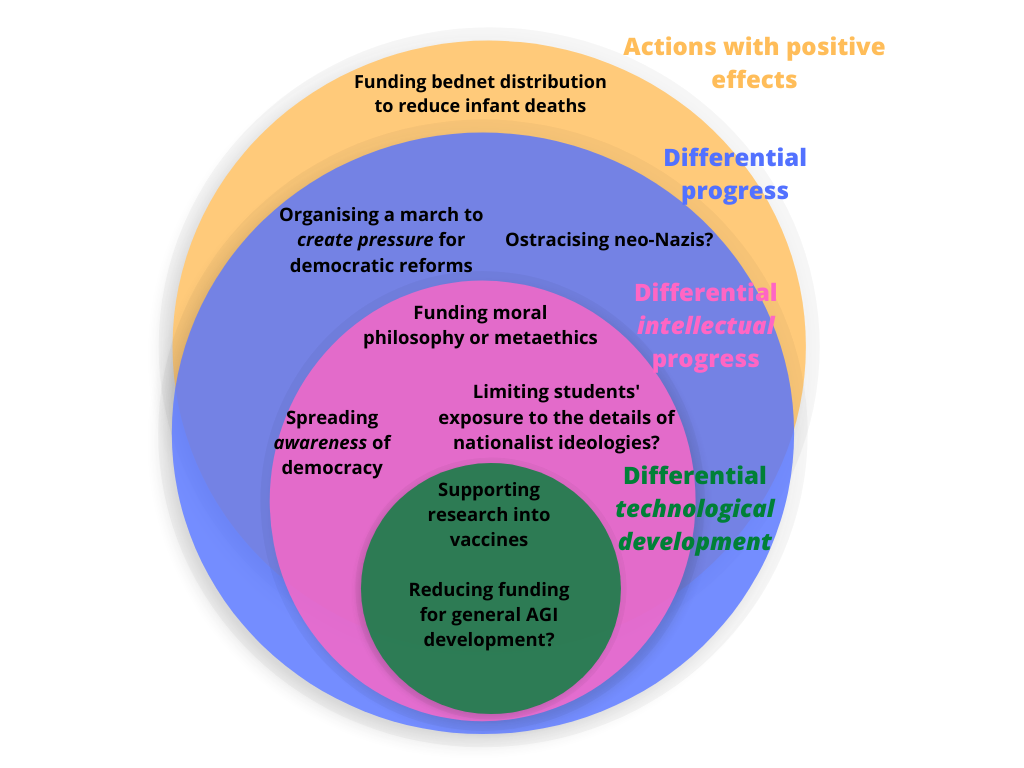

One final thing to note is that differential progress refers to “prioritizing risk-reducing developments over risk-increasing developments”. It does not simply refer to “prioritizing world-improving developments over world-harming developments”, or "prioritizing good things over bad things". In other words, the concepts of "differential progress" and "good actions" are highly related, and many actions will fit inside both concepts, but they are not synonymous.[6]

More specifically, there may be some "good actions" that are good for reasons unrelated to risks (by which we particularly mean catastrophic or existential risks). For example, it's plausible that something like funding the distribution of bednets in order to reduce infant deaths is net beneficial, due to improvements in present people's health and wellbeing, rather than due to changes in the risks humanity faces.[7]

Meanwhile, differential progress will always have at least some positive effects, in expectation, as it always results in a net reduction in risks. But there may be times when differential progress is sufficiently costly in other ways, unrelated to risks, that it's not beneficial on balance. For example, slowing the advancement of a technology that is incredibly slightly risky, and that would substantially increase the present population's wellbeing once developed, could classify as differential progress but not as a "good action".

Thus, we can represent differential progress, differential intellectual progress, and differential technological development as highly overlapping with, but not perfect subsets of, "good actions":

Closing remarks

I hope you’ve found this post clear and useful. If so, you may also be interested in my prior post, which similarly summarises and clarifies Bostrom’s concept of information hazards, and/or my upcoming post, which will summarise his concept of the unilateralist’s curse and discuss how it relates to information hazards and differential progress.

My thanks to David Kristoffersson and Justin Shovelain for feedback on a draft of this post.

Other sources relevant to this topic are listed here.

It's also possible that I am extending the concepts of differential intellectual progress or differential progress more generally beyond what they were originally intended to mean, and that this is what makes the positive connotations of "progress" seem inappropriate. Personally, I think that, in any case, my way of interpreting and using of these concepts is useful. Further discussion in the comments. ↩︎

It’s very possible that someone has made that explicit, and I’ve just missed it. ↩︎

Again, my focus here is on clarifying concepts that allow us to have such discussions, rather than defending any specific claims about what increases vs decreases risks. I included economic growth in both lists of examples because its effects are particularly debated; see here for a recent analysis. ↩︎

I later wrote another, possibly clearer explanation of the distinction I have in mind between these three concepts in these comments. ↩︎

Two other potential reasons:

- Things like restricting access to knowledge or banning certain lines or research seems to have a pretty patchy track record. If this is true, then we should probably have a higher standard of proof for thinking that that's a good idea than for thinking something like "Increase funding to AI safety" is a good idea.

- There can be various benefits from “progress” that aren’t related to existential risks, or that reduce some risks while increasing others. As such, advancing risk-reducing progress may have both a positive intended effect and positive side effects, whereas slowing risk-increasing progress may have negative side effects, even if it has a positive intended effect and is indeed somewhat good on balance.

But I think that this is a complicated question, and that these claims require more justification and evidence that I can provide in this post; I raise these claims merely as potential considerations. ↩︎

Here I'm using "differential progress" as if it refers to a principle or action. I would personally also be happy to use it to refer to an outcome or effect, such as saying that we have "achieved" or are "working towards" differential progress if the outcome that we aim for is to have more risk-reducing developments and less risk-increasing ones. ↩︎

Again, my point is to illustrate concepts; an assessment of how bednet distribution affects risks, and how this in turns affects the overall value of bednet distribution, is far beyond the scope of this post. ↩︎

sbehmer @ 2020-02-09T18:46 (+8)

Thanks for the post!

For people especially interested in this topic, it might be useful to know that there's a literature within academic economics that's very similar called "Directed Technical Change". See Acemoglu (2002) for a well-cited reference.

Although that literature has mostly focused on how different technological developments will impact wage inequality, the models used can be applied (I think) to a lot of the topics mentioned in your post.

EdoArad @ 2020-02-07T16:36 (+5)

I appreciate, again, the clear writing and the clarification of terms.

A minor quibble:

Differential progress also includes slowing risk-increasing progress.

I don't think that should count as progress (unless it was some sort of "progress" that led to that). You may still have Differential Actions which could either increase safety or lower risk. I guess I'm not sure what is progress.

MichaelA @ 2020-02-07T17:04 (+4)

Thanks!

And yes, I think that's a fair point. (David also said the same when giving feedback.) This is why I write:

Also note that we’re using “progress” here as a neutral descriptor, referring to something that could be good or could be bad; the positive connotations that the term often has should be set aside.

I think that if I could unilaterally and definitively decide on the terms, I'd go with "differential technological development" (so keep that one the same), "differential intellectual development", and "differential development". I.e., I'd skip the word "progress", because we're really talking about something more like "lasting changes", without the positive connotations.

But I arrived a little late to set the terms myself :D

I.e., the term "differential intellectual progress" is already somewhat established, as is "differential progress", though to a slightly lesser extent. It's not absolutely too late to change them, but I'd worry about creating confusion by doing so, especially in a summary-style post like this.

However, it is true that my specific examples include some things that sound particularly not like progress at all, such as spread of nationalism and egoism. In contrast, Muehlhauser and Salamon's examples of "risk-increasing progress" sound more like the sort of thing people might regularly call "progress", but that they're highlighting could increase risks.

My current thinking is that how I've sliced things up (into something like lasting changes in techs, then lasting changes in ideas, then lasting changes of any sort) does feel most natural, and that the way that this makes the usage of the term "progress" confusing is a price worth paying.

But I'm not certain of that, and would be interested in others' thoughts on that too.

David_Kristoffersson @ 2020-02-08T10:13 (+3)

I think that if I could unilaterally and definitively decide on the terms, I'd go with "differential technological development" (so keep that one the same), "differential intellectual development", and "differential development". I.e., I'd skip the word "progress", because we're really talking about something more like "lasting changes", without the positive connotations.

I agree, "development" seems like a superior word to reduce ambiguities. But as you say, this is a summary post, so it might not the best place to suggest switching up terms.

Here's two long form alternatives to "differential progress"/"differential development": differential societal development, differential civilizational development.

Lizka @ 2022-01-15T01:33 (+4)

This post is concise and clear, and was great for helping me understand the topics covered when I was confused about them. Plus, there are diagrams! I'd be excited to see more posts like this.

[Disclaimer: this is just a quick review.]

adamShimi @ 2020-02-08T15:36 (+2)

Thanks a lot for this summary post! I did not know of these concepts, and I feel they are indeed very useful for thinking about these issues.

I do have some trouble with the distinction between intellectual progress and progress though. During my first reading, I felt like all the topics mentioned in the progress section were actually about intellectual progress.

Now, rereading the post, I think I see a distinction, but I have trouble crystallizing it in concrete terms. Is the difference about creating ideas and implementing them? But then it feels very reminiscent of the whole fundamental/applied research distinction, which gets blurry very fast. And even the applications of ideas and solutions requires a whole lot of intellectual work.

Maybe the issue is with the word intellectual? I get that you're not the one choosing the terms, but maybe something like fundamental progress or abstraction progress or theoretical progress would be more fitting? Or did I miss some other difference?

MichaelA @ 2020-02-08T18:11 (+2)

Thanks for that feedback!

I get why you'd feel unsure about those points you mention. That's one of the things I let stay a bit implicit/fuzzy in this post, because (a) I wanted to keep things relatively brief and simple, and (b) I wanted to mostly just summarise existing ideas/usages, and that's one point where I think existing usages left things a bit implicit/fuzzy.

But here's roughly how I see things, personally: The way Tomasik uses the term "differential intellectual progress" suggests to me that he considers "intellectual progress" to also include just spreading awareness of existing ideas (e.g., via education or Wikipedia), rather than conceiving of new ideas. It seems to me like it could make sense to limit "intellectual progress" to just cases where someone "sees further than any who've come before them", and not include times when individuals climb further towards the forefront of humanity's knowledge, without actually advancing that knowledge. But it also seems reasonable to include both, and I'm happy to stick with doing so, unless anyone suggests a strong reason not to.

So I'd say "differential intellectual progress" both includes adding to the pool of things that some human knows, and just meaning that some individual knows/understands more, and thus humanity's average knowledge has grown.

None of this directly addresses your questions, but I hope it helps set the scene.

What you ask about is instead differential intellectual progress vs differential progress, and where "implementation" or "application" of ideas fits. I'd agree that fundamental vs applied research can be blurry, and that "even the applications of ideas and solutions requires a whole lot of intellectual work." E.g., if we're "merely implementing" the idea of democracy in a new country, that will almost certainly require at least some development of new knowledge and ideas (such as how to best divide the country into constituencies, or whether a parliamentary or presidential system is more appropriate for this particular country). These may be "superficial" or apply only in that location, and thus not count as "breakthroughs". But they are still, in some sense, advancements in humanity's knowledge.

I'd see it as reasonable to classify such things as either "differential intellectual progress" or "differential progress". I think they're sort-of edge cases, and that the terms are a bit fuzzy, so it doesn't matter too much where to put them.

But there are also things you'd have to do to implement democracy that aren't really best classified as developing new ideas or having individuals learn new things. Even if you knew exactly what form of democracy to use, and exactly who to talk to to implement this, and exactly what messages to use, you'd still need to actually do these things. And the shift in their political attitudes, values, ideologies, opinions, etc., seem best thought of as influenced by ideas/knowledge, but not themselves ideas/knowledge. So these are the sorts of things that I consider clear cases of "progress" (in the neutral, descriptive sense of "lasting changes", without necessarily having positive connotations).

Does that clarify things a bit? Basically, I think you're right that a lot of it is fuzzy/blurry, but I do think there are some parts of application/implementation that are more like just actually doing stuff, or people's opinions changing, and aren't in themselves matters of intellectual changes.

adamShimi @ 2020-02-09T19:02 (+2)

Thanks for the in-depth answer!

Let's take your concrete example about democracy. If I understand correctly, you separate the progress towards democracy into:

- discovering/creating the concept of democracy, learning it, spreading the concept itself, which is under the differential intellectual progress.

- convince people to implement democracy, do the fieldwork for implementing it, which is at least partially under the differential progress.

But the thing is, I don't have a clear criterion for distinguishing the two. My first ideas were:

- differential intellectual progress is about any interaction where the relevant knowledge of some participant increases (in the democracy example, learning the idea is relevant, learning that the teeth of your philosophy teacher are slightly ajar is not). And then differential progress is about any interaction making headway towards a change in the world (in the example the implementation of democracy). But I cannot think of a situation where no one learns anything relevant to the situation at hand. That is, for these definitions, differential progress is differential intellectual progress.

- Another idea is that differential intellectual progress is about all the work needed for making rational agents implement a change in the world, while differential progress is about all the work needed for making humans implement a change in the world. Here the two are clearly different. My issue there stems with the word intellectual: in this case Amos and Tversky's work, and pretty much all of behavioral economics, is not intellectual.

Does any of these two criteria feel right to you?

MichaelA @ 2020-02-09T20:37 (+3)

I think the first of those is close, but not quite there. Maybe this is how I'd put it (though I'd hadn't tried to specify it to this extent before seeing your comment):

Differential progress is about actions that advance risk-reducing lasting changes relative to risk-increasing progress, regardless of how these actions achieve that objective.

Differential intellectual progress is a subset of differential progress where an increase in knowledge by some participant is a necessary step between the action and the outcomes. It's not just that someone does learn something, or even that it would necessarily be true that someone would end up having learned something (e.g., as an inevitable outcome of the effect we care about). It's instead that someone had to learn something in order for the outcome to occur.

In the democracy example, if I teach someone about democracy, then the way in which that may cause risk-reducing lasting changes is via changes in that person's knowledge. So that's differential intellectual progress (and thus also differential progress, since that's the broader category).

If instead I just persuade someone to be in favour of democracy by inspiring them or making liking democracy look cool, then that may not require them to have changes in knowledge. In reality, they're likely to also "learn something new" along the lines of "this guy gave a great speech", or "this really cool guy likes democracy". But that new knowledge isn't why they now want democracy; the causal pathway went via their emotions directly, with the change in their knowledge being an additional consequence that isn't on the main path.

(Similar scenarios could also occur where a change in knowledge was necessary, such as if they choose to support democracy based on now explicitly thinking doing so will win them approval from me or from their friends. I'm talking about cases that aren't like that; cases where it's more automatic and emotion-driven.)

Does that seem clearer to you? (I'm still writing these a bit quickly, and I still think this isn't perfectly precise, but it seems fairly intuitive to me.)

MichaelA @ 2020-02-09T20:41 (+3)

And then we could perhaps further say that differential technological development is when a change in technology was a necessary step for the effect to occur. Again, it's not just an inevitable consequence of the chain of events, but rather something on the causal pathway between our action and the outcome we care about.

I think it's possible that this framing might make the relationship between all three clearer than I did in this post. (I think in the post, I more just pointed to a general idea and assumed readers would have roughly the same intuitions as me - and the authors I cite, I think.)

(Also, my phrasing about "causal pathways" and such is influenced by Judea Pearl's The Book of Why, which I think is a great book. I think the phrasing is fairly understandable without that context, but just thought I'd add that in case it's not.)

adamShimi @ 2020-02-09T21:30 (+2)

That's a great criterion! We might be able to find some weird counter-example, but it solves all of my issues. Because intellectual work/knowledge might be a part of all actions, but it isn't necessary on the main causal path.

I think this might actually deserve its own post.

MichaelA @ 2020-02-19T14:17 (+2)

I've gone with adding a footnote that links to this comment thread. Probably would've baked this explanation in if I'd had it initially, but I now couldn't quickly find a neat, concise way to add it.

Thanks again for prompting the thinking, though!

MichaelA @ 2020-02-10T07:34 (+2)

Great!

And thanks for the suggestion to make this idea/criterion into its own post. I'll think about whether to do that, just adjust this post's main text to reflect that idea, or just add a footnote in this post.

Ray P. @ 2021-10-06T08:52 (+1)

Thank you...very helpful...

MichaelA @ 2020-02-19T14:07 (+1)

I've updated this post since initial publication, particularly to further discuss the terms "progress" vs "development" (and their connotations) and to add "Relationship to all "good actions"". This was mostly a result of useful comments on the post that prompted me to think some things through further, and some offline discussions.

In the interests of over-the-top transparency, the original version of the post can be found here.

MichaelA @ 2020-02-19T08:51 (+1)

On a different post of mine on LW, which quoted this one, Pattern commented:

"What we do have the power to affect (to what extent depends on how we define “we”) is the rate of development of various technologies and potentially the sequence in which feasible technologies are developed and implemented. Our focus should be on what I want to call differential technological development: trying to retard the implementation of dangerous technologies and accelerate implementation of beneficial technologies, especially those that ameliorate the hazards posed by other technologies."

An idea that seems as good and obvious as utilitarianism.

I agree that the idea seems good and obvious, in a sense. But beware hindsight bias and the difficulty of locating the hypothesis. I.e., something that seems obvious (once you hear it) can be very well worth saying. I think it's apparent that most of the people making decisions about technological development (funders, universities, scientists, politicians, etc.) are not thinking in terms of the principle of differential technological development.

Sometimes they seem to sort-of approximate the principle, in effect, but on closer inspection the principle would still offer them value (in my view).

E.g., concerns are raised about certain biological research with "dual use" potential, such as gain of function research, and people do call for some of that to be avoided, or done carefully, or the results released less widely. But even then, the conversation seems to focus almost entirely on whether this research is net beneficial, even slightly, rather than simultaneously also asking "Hey, what if we didn't just try to avoid increasing risks, but also tried to direct more resources to decreasing risks?" Rob Wiblin made a relevant point (and then immediate self-counterpoint, as is his wont) on the latest 80k episode:

If you really can’t tell the sign, if you’re just super unconfident about it, then it doesn’t seem like it’s probably a top priority project. If you’re just unsure whether this is good or bad for the world, I don’t know, why don’t you find something that’s good? That you’re confident is good. I suppose you’d be like, “Well, it’s a 55-45 scenario, but the 55 would be so valuable.” I don’t know.

Having said that, I feel I should also re-emphasise that the principle is not a blanket argument against technological development; it's more like highlighting and questioning a blanket assumption often implicitly made the other direction. As Bostrom writes in a later paper:

Technology policy should not unquestioningly assume that all technological progress is beneficial, or that complete scientific openness is always best, or that the world has the capacity to manage any potential downside of a technology after it is invented. [emphasis added]

Pattern's comment goes on to say:

But what if these things come in cycles? Technology A may be both positive and negative, but technology B which negates its harms is based on A. Slowing down tech development seems good before A arrives, but bad after. (This scenario implicitly requires that the poison has to be invented before the cure.)

I think this is true. I think it could be fit into the differential technological development framework, as we could say that Technology A, which appears "in itself" risk-increasing, is at least less so than we thought, and is perhaps risk-reducing on net, if we also consider how it facilitates the development of Technology B. But that's not obvious or highlighted in the original formulation of the differential technological development principle.

Justin, also of Convergence, recently wrote a post something very relevant to this point, which you may be interested in.