Addressing challenges for s-risk reduction: Toward positive common-ground proxies

By Teo Ajantaival @ 2025-03-22T17:50 (+52)

1. Introduction

One of the most reasonable ethical aims from a variety of perspectives is to focus on s-risk reduction, namely on steering the future away from paths that would entail vastly more suffering than Earth so far. The research field of s-risk reduction faces many challenges, such as narrow associations to particular ethical views, perceived tensions with other ethical aims, and a deep mismatch with the kinds of goals that most naturally motivate us. Additionally, even if one strongly endorses the goal of s-risk reduction in theory, there is often great uncertainty about what pursuing this goal might entail in practice.

To address these challenges, here I aim to briefly:

- Highlight how s-risk reduction can be highly valuable from a wide range of perspectives, not just suffering-focused ones. (§2)

- Address perceived tensions between s-risk reduction and other aims, such as reducing extinction risk or near-term suffering. While tradeoffs do exist and we shouldn’t overstate the degree of alignment between various aims, we shouldn’t understate it either. (§2)

- Discuss motivational challenges, why s-risk reduction seems best pursued by adopting an indirect “proxy focus”, and why the optimal approach might often be to focus specifically on positive proxies (e.g. boosting protective factors). (§3)

- Collect some preliminary conclusions about what the most promising proxies for s-risk reduction might be, including general protective factors that could be boosted in society over time, as well as personal factors among people seeking to reduce s-risks in healthy and sustainable ways. (§4)

For an introduction to s-risk, see, for instance, DiGiovanni (2023), Baumann (2017, 2022a), or the Rational Animations video titled “S-Risks: Fates Worse Than Extinction” (2024). The Baumann sources are also freely available in an audio format.

2. Common ground

At first glance, s-risk reduction may seem like an ethical priority only for those whose views fall under the umbrella of suffering-focused ethics: views that give a foremost priority to the reduction of suffering.[1] And it’s probably true that many of the people who most prioritize s-risk reduction do so because they see at least some scenarios of future suffering as unoffsettable, for ethical or empirical reasons.

However, one can also find s-risk reduction highly valuable without being particularly suffering-focused. For instance, s-risk reduction can be a shared priority between various consequentialist, deontological, or virtue-ethical frameworks that value the prevention of vast disasters with many very badly off victims, even if their underlying reasons may differ.[2]

The following subsections highlight some complementary ways in which s-risk reduction can represent valuable ‘common ground’:

- §2.1 (Ethical common ground): Various ethical views agree that non-extinctionist interventions for s-risk reduction are highly desirable for improving the future’s expected value.

- §2.2 (Practical common ground): Targeting shared risk factors can advance multiple ethical aims simultaneously and help increase robustness under uncertainty.

- §2.3 (Strategic common ground): Even without shared visions of which exact futures to aim for, people with diverse views can probably agree on the strategy of seeking to create and maintain a safe distance from worst-case risks.

2.1. Better lotteries

S-risk reduction is valuable from many perspectives concerned with the trajectory of the long-term future, even if they are not particularly suffering-focused. Rational Animations illustrates s-risks as a poisoned future timeline in which countless future beings suffer fates worse than nonexistence. They also note, based on Althaus & Gloor (2016), that merely avoiding risks of extinction is like buying more tickets in a lottery with s-risks among the possible outcomes. Regardless of whether we would like to buy more of such tickets, reducing s-risks increases the average value of the tickets that we already have, making the overall lottery comparatively more attractive.

This brings us to the question of possible tensions between s-risk reduction and extinction risk reduction. For those who mostly prioritize s-risk reduction, a hypothetical intervention aimed at pure extinction risk reduction might sound risky if it only increases the size or duration of the future without improving its quality (“buy more tickets without reducing the proportion of S-faced dice”).

However, there is also substantial common ground, because virtually all views can agree that it is valuable to reduce s-risks if all else is equal. In particular, even if people have different views about what matters most about the long-term future, we can still agree that targeted, non-extinctionist efforts toward s-risk reduction would help move the expected value of the future in a better direction.

2.2. Shared risk factors

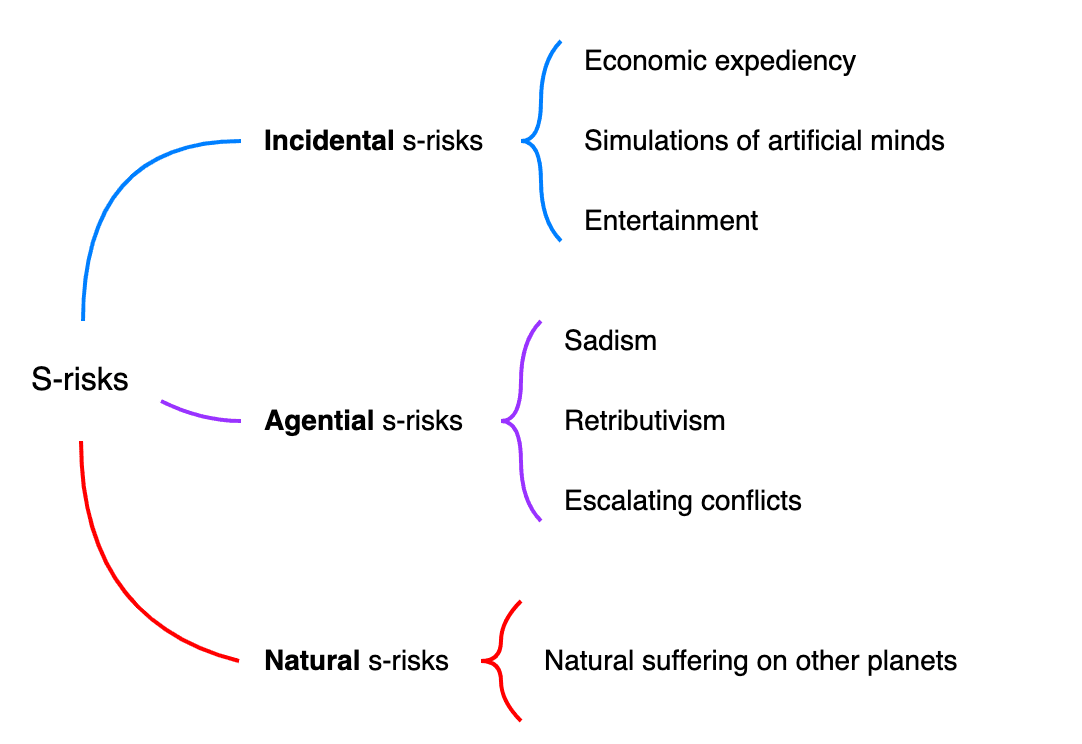

As summarized in DiGiovanni (2023), s-risks might result from:

- unintended consequences of pursuing large-scale goals (“incidental s-risks”);

- intentional harm by intelligent beings with influence over many resources (“agential s-risks”);

- processes that occur without the intervention of moral agents (“natural s-risks”).

These three broad classes of s-risks are illustrated in Figure 2 above. Each of these classes of s-risks may be related to particular risk factors. The concept of risk factors is commonly used in medicine, in which some risk factors make us more prone to particular kinds of diseases, while others tend to broadly increase our susceptibility to a range of adverse health outcomes.

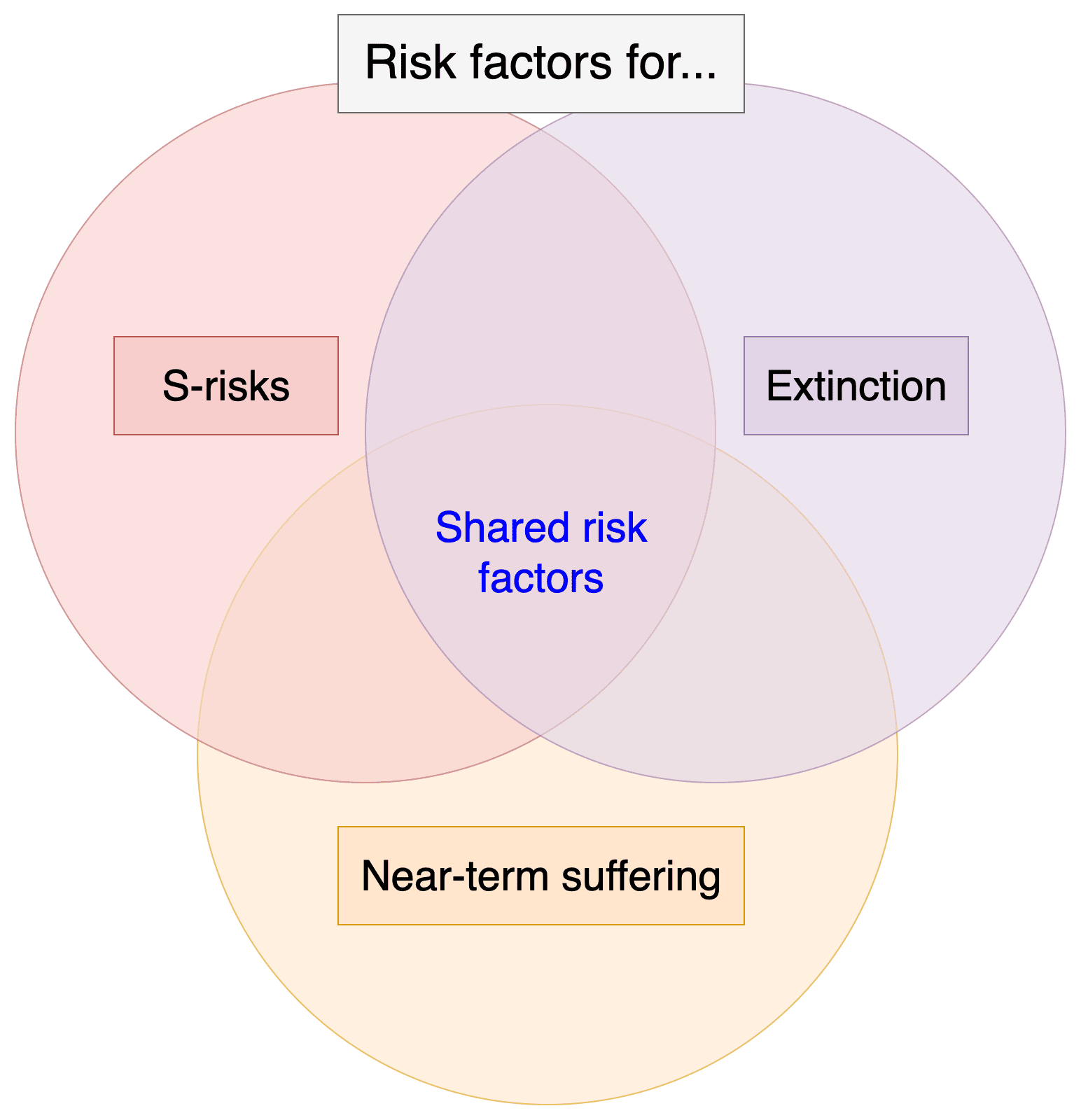

Similarly, some risk factors for s-risks may specifically increase the likelihood of s-risk scenarios without substantially affecting other risks, while other risk factors may also increase other risks, such as the risk of extinction or near-term suffering.[3] Reducing these broader risk factors may be seen as ‘common ground’ between different focus areas.

Such common-ground risk factors might include, for example:

- narrow or insufficient moral concern (e.g. neglect of non-human beings or future generations);

- lack of coordinated efforts to counter harmful societal trends;

- strong incentives to externalize or ignore harm;

- sadistic, vengeful, or retributive tendencies among powerful agents or society at large;

- ideological polarization, fanaticism, and escalating conflicts;

- scale and severity of suffering amplified by advanced technology.

Thus, many forms of s-risk reduction may not only represent common ground between different ethical views, but they may also address a shared set of practical problems between different cause areas.[4]

In practice, when we are uncertain about which risks to prioritize, we can seek to adopt a broad focus on shared risk factors so as to mitigate multiple issues at the same time. This common-ground approach can also serve as a bridge between those who might otherwise remain siloed within their specialized areas. Thus, it can help achieve not only more effective action under uncertainty, but also more win-win cooperation by advancing shared aims.[5]

Additionally, beyond a shared focus on particular risk factors, people with diverse views also have significant common ground in wanting to create a safe distance from the very worst future outcomes. This will be briefly explored in the next section.

2.3. Staying safe

The prospect of multiple risk factors ties into what has been called “the bounding approach to avoiding worst-case outcomes” (Vinding, 2022d, Chapter 9).

In a nutshell:

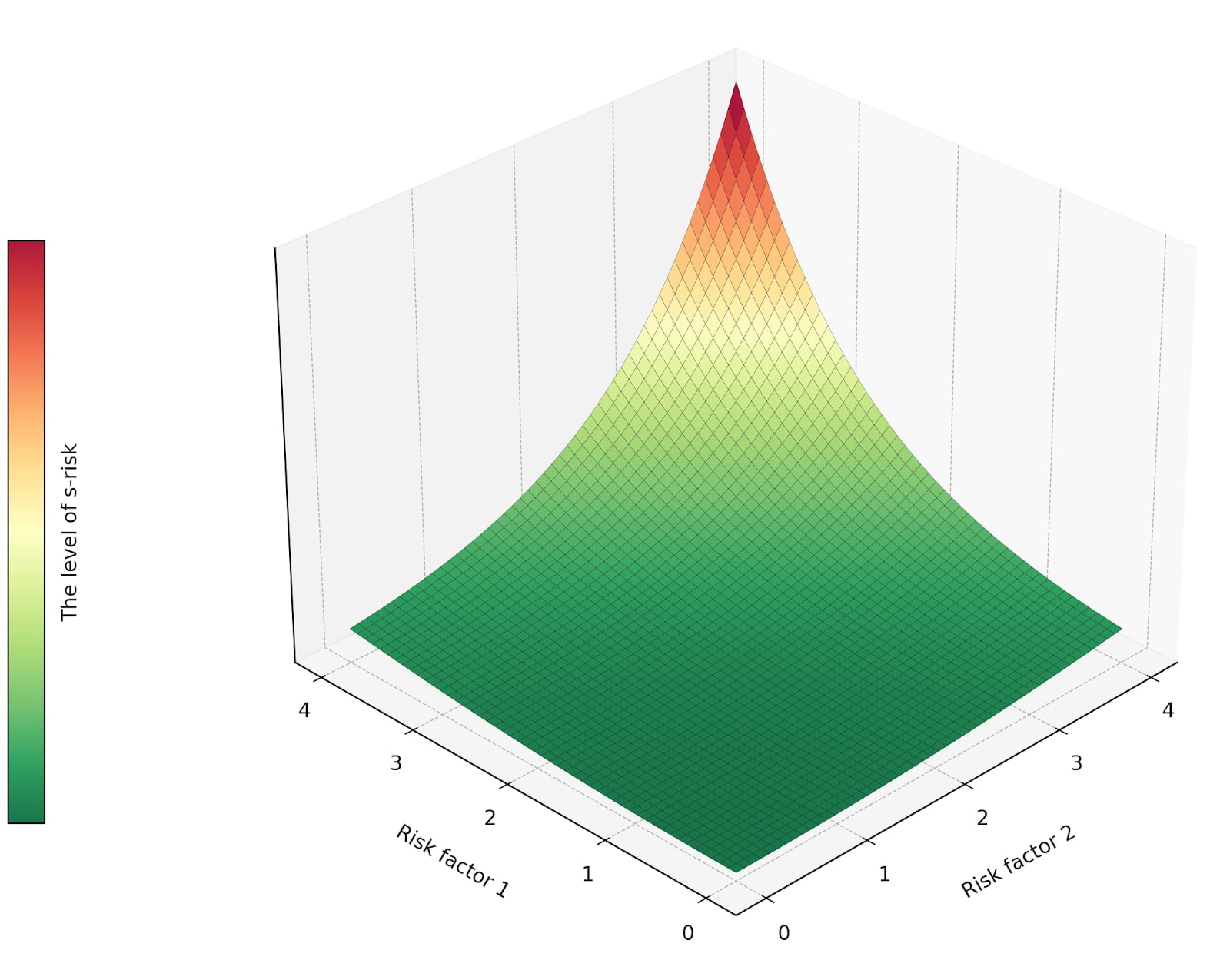

- We face a high-dimensional landscape of worst-case risks, with different dimensions representing different kinds of s-risks.

- A crucial aim is to “bound us off” from these risks, keeping a safe distance from all the red peaks in this landscape (cf. Figure 4).

- Even if we don’t know which particular risks are most worrisome, we can still likely pursue actions and policies that are robustly positive, in that they help protect us from many different risks at the same time.

- In other words, we need not know the exact details of what the “danger zone” looks like in order to create a safe distance and protect us from getting there.

- Instead, we can pursue a strategy of robust worst-case safety, namely to gradually build and refine policies that steer us toward and within the low-risk green zone in the space of worst-case risks.

This also ties into the health analogy made in Baumann (2019):

- Key risk factors, such as poor diet or lack of exercise, are not themselves adverse health outcomes, but they increase the risk of a wide range of health problems. By focusing on key risk factors, we can often give broadly protective health advice without needing to analyze specific diseases or individual differences.

- Similarly, if we can identify reliable risk factors for s-risks, we can infer robust and effective ways to simultaneously reduce a wide range of s-risks (that is, to “stay green” in the risk landscape).

Finally, as in the case of health, the risk factors will likely have sharply compounding interactions with each other (illustrated in Figure 4).[6] Thus, plausibly the worst expected s-risks occur in worlds where several risk factors coincide and create a superlinear effect.

Overall, this suggests that the practically optimal strategy for robust worst-case is not to seek to eliminate any particular risk factor altogether, but rather to broadly maintain relatively safe levels across a wide range of risk factors. This way, we would maximize our chances of staying safe from the especially hazardous interactions between risk factors.

3. Need for proxies

If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.[7]

In this section, I suggest that s-risk reduction is generally best pursued by adopting an indirect “proxy focus”.

A similar point has been made by Vinding (2022d, Chapter 9), who argues that it is often helpful to use a framework of proxies — ‘proxies for future suffering’ — in order to better evaluate policies aimed at reducing future suffering.[8]

As discussed above, we can already make a lot of progress by identifying reliable risk factors: factors that tend to increase future suffering. For example, a stable increase in sadism, especially among the most powerful agents, seems like a reliable risk factor that is worth reducing. And the same seems true of a stable increase in the willingness to create suffering in general.

Suffering-conducive factors like these may be seen as “negative proxies” for s-risk reduction, as they are something that we generally want to reduce.

However, we may also have various psychological and practical reasons to translate these negative proxies into their opposites, namely protective factors that we generally want to advance and promote.

Thus, we might make even more progress by treating the search for risk factors as a stepping stone toward identifying promising “positive proxies” for s-risk reduction, and by organizing our practical efforts largely around these positive proxies.[9]

Below, I focus on the value of having proxy goals for s-risk reduction that are positive in the following three senses:

- Positive for motivation (ideally more so than a direct focus on the goal of s-risk reduction itself).

- Positive for coordination (ideally not only for s-risk reduction, but also for other goals, possibly representing ‘win-win’ ways to align broader efforts with s-risk reduction).

- Positive for measurability (enabling better evaluation, prioritization, and sense of progress).

3.1. Positive for motivation

Focusing on the concept of s-risk reduction is probably useful for the purposes of discussion and analysis, as it offers a relatively unambiguous way to make sure that we are ultimately talking about the same thing.

But in practice, there is often a deep motivational mismatch between s-risk reduction and the kinds of goals that more naturally motivate us. By ‘deep’, I mean that the mismatch is often quite strong, and takes place along many different goal dimensions at the same time.

Table 1 below shows a non-exhaustive set of dimensions along which our goals can vary, chosen to illustrate this motivational mismatch.

Table 1. Some goal dimensions, intended to illustrate the kinds of goals that might naturally motivate us (left) more than s-risk reduction (right).

| A goal can be… | ||

| 1. | Concrete (“post more of this specific content on social media”) | Abstract (“reduce uncertainty in cause prioritization”) |

| 2. | Emotionally Salient (“help a friend in need”) | Emotionally Distant (“help also less relatable, unseen minds”) |

| 3. | Completable (“solve this; get things done”) | Endless (“keep reducing the risk”) |

| 4. | Under Direct Control (“I am easily able to do this”) | Only Indirectly Influenceable (“I could maybe nudge some probabilities”) |

| 5. | Safe (“even if you fail, you’ll do no harm”) | High-Stakes (“you might have a significantly negative impact”) |

| 6. | Constructive (“build this; create that; show your progress”) | Preventive (“even if you do it right, there might be nothing to show for it”) |

| 7. | Measurable (“optimize this metric”) | Nebulous (“what? how? figure it out; poorly defined next steps”) |

It’s hard to generally say which dimensions are most relevant for motivation, and there is surely a lot of variation between individuals in this regard. Yet most people can probably relate to the inner struggle of trying to bridge this motivational mismatch, namely of endorsing a goal with the right-column attributes while feeling drawn to goals that are better characterized by the bolded attributes on the left.

Thus, even if we strongly endorse the goal of s-risk reduction in theory, in practice we may greatly enhance our motivation by translating it into proxy goals of the kind found in the left column. I will point to some plausible translations of this kind in Section 4.

3.2. Positive for coordination and shared aims

Progress on large-scale goals like s-risk reduction will likely require broad coordination, extending beyond those who explicitly prioritize our particular goal.[10]

This connects to earlier points about common ground and shared risk factors between different focus areas. For example, it would be an uphill battle to only pursue s-risk reduction in ways that would mostly be perceived as diverting resources away from other important problems.

A more effective approach might be to seek “common-ground proxies” that could help align s-risk reduction with other widely supported goals. This way, we could collectively benefit from the natural overlap with other priorities, such as by increasing our collective ability to reduce s-risks without requiring everyone to explicitly prioritize this goal.

3.3. Positive for measurability

Perhaps the most fundamental need for proxies is the need for better measurability. After all, even with direct motivation and coordination toward the broader goal, we would still need to translate it into some concrete steps and tangible subgoals in practice. Otherwise, we would have no reliable metrics for moving in a better direction to begin with.

Measurability can also boost motivation and coordination. With clearer and more actionable metrics for tracking progress over time, we can better sustain a motivating sense of momentum and shared alignment with possible solutions.

While measurable proxies are indispensable, we also need to remember that any framework of proxies is ultimately only an imperfect tool, subject to continuous, gradual refinement, and never fully aligned with the actual goal: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”[11] By keeping this in mind, we can strive to maintain a healthy skepticism of any proposed final answers, remain open to identifying better proxies, and avoid the pitfall of over-optimizing for a proxy that is not the actual goal.

4. Promising proxies

The task of identifying promising proxies is by no means easy. We often face vast or even paralyzing uncertainty when trying to estimate the long-term effects of our actions, a general problem known as cluelessness. For instance, s-risks could be highly sensitive to some factors that are unknown or unpredictable from our current position, making it unclear which actions will make things better rather than worse.

We still have reasons to keep trying. After all, if we can do something to reduce s-risks, it could be the best thing we ever do, protecting countless future beings from extreme harm. (Corollary: We should also avoid premature action, given that increasing s-risks could be the worst thing we ever do.)

We might have some empirically reasonable heuristics for identifying promising proxies. Thus, even if cluelessness might remain a challenge, we may avoid being completely paralyzed by it. For instance, below are two perspectives on how the problem of cluelessness need not be insurmountable.

- Vinding (2022c) argues that vast uncertainty about outcomes need not imply (similarly) vast uncertainty about strategies. After all, we do have vast outcome uncertainty in a wide range of domains, such as games, business, and politics, in which we can nevertheless identify strategies that are reasonably robust and beneficial across different scenarios. We might expect a similar pattern to hold in the broader domain of impartial suffering reduction, so that even there we could identify at least some heuristics for what would likely be a step in the right direction.

- DiGiovanni (2023, §2.1) suggests that we could focus on avoiding foreseeable, near-term scenarios that could “lock in” conditions for eventual large-scale suffering, what he calls ‘s-risk-prone persistent states’. And beyond merely avoiding disfavorable lock-in conditions that are realistically foreseeable to us, we can also focus on building favorable conditions for future generations, enabling our successors to navigate the risk landscape with more resources, knowledge, and foresight.

Below, I collect some preliminary conclusions about what the most promising proxies for s-risk reduction might be. We may roughly divide the proxies into general protective factors that could be boosted in society over time, as well as personal protective factors among people seeking to reduce s-risks in healthy and sustainable ways.

4.1. General proxies

Here is a non-exhaustive list of suggested general proxies for s-risk reduction, with footnotes pointing to further reading. While these proxies are reflected in many s-risk-focused efforts to date, there is still considerable uncertainty and no clear consensus on what the most promising proxies are. Thus, more research is still needed, including research to compare these proxies against possibly better ideas that could still be missing from this list.

Movement building and capacity building: Expand the movement of people who strive to reduce s-risks, and build a healthy and sustainable culture around this movement. Increase the insights and resources available to the movement.[12]

Promoting concern for suffering: Increase the level of priority that people devote to the prevention of suffering, and increase the amount of resources that society devotes to its alleviation.[13]

Promoting cooperation: Increase society’s ability and willingness to engage in cooperative dialogues and positive-sum compromises that can help steer us away from bad outcomes.[14]

Worst-case AI safety (cooperative AI, fail-safe AI): Work to ensure that AI systems are less conducive to s-risks, especially under worst-case conditions such as escalating conflicts. Design training environments or other technical measures to discourage extremely harmful AI behaviors.[15]

Safeguards against malevolence: Research, develop, and implement safeguards to mitigate the impact of malevolent actors with high levels of harmful tendencies like sadism, psychopathy, spitefulness, retributivism, or vengefulness.[16]

To be clear, this is just one way to describe some high-level ideas that have each received substantial support within the s-risk community. This doesn’t mean that the only or best way to contribute to s-risk reduction would necessarily be to focus on these ideas. Depending on one’s skills and interests, the best way to contribute could be to specialize in some of these areas or to explore additional avenues of contribution that go beyond these areas.

Also, depending on one’s views on cluelessness or uncertainty, one might wish to devote special priority to common-ground proxies that appear to be relatively robust across a variety of perspectives. For example, if one is uncertain how to prioritize between near-term and long-term suffering, one could seek out proxies that would target shared risk factors, as discussed in §2.2.

More generally, we can roughly translate the shared risk factors mentioned in §2.2 into a high-level list of promising “common-ground positive proxies”. This list of proxies is similar to the more s-risk-focused list above, but expressed in more common-ground terms:

- Working toward optimally inclusive moral concern.

- Coordinating efforts to counter harmful societal trends.

- Promoting cooperative norms around emerging technologies.

- Correcting for incentives to ignore harm.

- Countering sadistic and vengeful tendencies among powerful agents.

- Steering away from fanaticism and escalating conflicts.

- Improving institutional epistemics.

In general, prioritizing common-ground proxies can also be more motivating (§3.1), as well as more conducive to creating a broad and effective movement (§3.2). The aims above can be highly valuable from a common-ground perspective focused on a wide range of goals besides s-risk reduction. The same seems true of the following personal factors, which can serve as a foundation for a wide range of altruistic goals.

4.2. Personal proxies

Beyond the question of which protective factors seem useful to boost in the wider world, we can also analyze various dimensions of personal development (“personal proxies”) in terms of what might be optimally conducive to altruistic impact, as illustrated in Figure 5.

These dimensions can include not only many different traits, virtues, and habits, but also various attitudes and mindsets that we can develop and apply in our daily lives.

Many of these dimensions are interrelated in ways that are too complex to visualize. Yet many of them are also quite distinct from each other, such that becoming highly developed in just one virtue, or across a narrow range of dimensions, might not in itself translate into development along the other dimensions.

While specialization can make a lot of sense at the level of general proxies, a better approach at the level of our supportive personal factors is plausibly to seek deliberate development across a wide range of dimensions. By picking the low-hanging fruit across many dimensions, we can build a strong foundation for altruistic impact, as well as better avoid the many common pitfalls of neglecting some key dimensions.

With this approach in mind, here is a non-exhaustive list of what might be some particularly promising dimensions of personal development for people seeking to reduce s-risks in healthy and sustainable ways.[17]

Finding and holding on to a sense of purpose: Studies suggest that we may greatly benefit by developing a strong, prosocial sense of higher purpose. For instance, Vinding has explored adopting a compassionate form of the Nietzschean “why”: “If one has a why? in life, one can bear almost any how?”.[18]

Developing healthy habits (foundations of wellbeing and productivity): Prioritizing healthy sleep, diet, exercise, and focus. Remembering that we are not so much seeking perfect results in any single area, but rather seeking optimal imperfection across all of them (given our practical constraints).[19]

Cultivating a virtue-based approach (practical, time-tested, and more robust against uncertainty): Beyond healthy habits, we also have strong reasons to adopt a virtue-based approach to altruistic impact. This provides us a solid foundation and an effective response to uncertainty, as it relies on adherence to widely respected virtues that generally lead to better outcomes, especially compared to their contrasting vices.[20]

Building a broad foundation of motivation: We don’t permanently become our best self or lastingly boost our motivation via any single action, like reading the right book once or endorsing a new moral theory that resonates with us. Especially if the cerebrally endorsed goal is highly abstract, we will likely benefit from continually renewing our motivation in more vivid and multifaceted ways. For instance, we can regularly engage with inspiring stories or watch footage of some highly virtuous acts, which can help support wholesome and uplifting feelings of moral elevation.[21]

Cultivating compassion for ourselves and others: Compassion may sound weak, as if real change were driven only by rational argument or anger at injustice. Misconceptions like these may lead us to neglect the numerous empirically supported benefits of active compassion cultivation, such as better overall health, improved resilience, and being driven by less painful and more pleasant emotions.[22]

Seeking healthy self-scrutiny (awareness of universal human biases): The human mind has many hidden parts, such as our tribal and coalitional status-seeking drives, which can distort even the best of our altruistic intentions. Probably none of us are immune to this, but we can strive to become more aware of it, and thereby learn to better navigate around many pitfalls in our social interactions and truth-seeking endeavors.[23]

Focusing mostly on positive and constructive goals: To consistently motivate us, our goals often need to be constructive and gradual. Thus, we might benefit from translating our broader goals into more motivating forms, such as the gradual construction of various resources. Analogous to the concept of potential energy in physics, we can see our lives as a quest to accumulate “positive impact potential” by cultivating healthy mindsets, becoming more knowledgeable, developing relevant skills, and so on, which can effectively contain immense positive value by increasing our potential to prevent extreme suffering.[24]

Adopting a multi-player perspective: By default, our drives for social status might pull us toward a single-player perspective of altruistic impact. For instance, we might give undue importance to us personally doing some highly visible or even heroically difficult project that would increase our own perceived impact and status in the eyes of others. However, altruistic impact is ultimately a multi-player effort. Thus, even if we have good reasons to prioritize our own projects, we can still aim for collective impact, which often flows through the more mundane and less visible roles in which we can effectively support the work of others.[25]

Approaching impact as a gradual process: When we are faced with current or anticipated scenarios of extreme suffering, we may feel an urgent need to immediately “get out there” and fix whatever we can. But in practice, optimizing our long-term impact is generally a gradual process. Specifically, we are not failing if we are patiently building up a range of relevant skills and resources at our own pace. On the contrary, instead of exerting maximum effort right away, the more patient strategy of incremental progress is often a better way to optimize our impact over time.[26]

Facing adversity in healthy ways: Beyond having compassion for ourselves, we can also adopt various additional tools for facing adversity. For instance, we can learn to skillfully update our expectations about our own situation, and thereby gain some degree of acceptance about what might be unavoidable. Additionally, to whatever degree is realistic to us, we can strive to better realize our strength to handle discomfort, take responsibility, and find the best ways to move forward with the resources we have.[27]

Replacing impact obsession with a sustainable impact mindset: Relatedly, we can find ways to improve how we relate to altruistic impact in general. Impact obsession is a complex phenomenon, with both helpful and counterproductive aspects. For an overall healthier approach, many have found it useful to also focus on things such as integrating conflicting desires, cultivating additional sources of meaning and self-worth, and learning skills to navigate difficult emotions.[28]

Dealing with uncertainty (easier said than done, probably a lifelong quest): Being patient with cravings for action and certainty. Researching crucial considerations that might drastically change the expected value of some naively promising interventions. Learning to accept, act, and sometimes withhold action under inevitable uncertainty. Recognizing when and how to seek more information instead of acting prematurely.[29]

Focusing on that which we can change (Serenity mindset): Seeking courage to change what we can, serenity to accept what we cannot, and wisdom to know the difference.[30]

The most effective approach to personal development will, of course, vary greatly between individuals. To identify the most promising focus areas in our own particular case, a useful first step could be to reflect on our main strengths and bottlenecks. We may then find it useful to focus on those dimensions that currently represent the greatest constraints, and the greatest room for growth, on our path toward sustainably contributing to s-risk reduction and other altruistic aims.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Riikka Ajantaival, Tobias Baumann, Simon Knutsson, and Magnus Vinding for reading a draft and providing helpful comments.

References

Althaus, D. & Baumann, T. (2020). Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/LpkXtFXdsRd4rG8Kb

Althaus, D. & Gloor L. (2016). Reducing Risks of Astronomical Suffering: A Neglected Priority. longtermrisk.org/reducing-risks-of-astronomical-suffering-a-neglected-priority

Althaus, D., Nguyen, C., & Harris, C. D. (2024). What is malevolence? On the nature, measurement, and distribution of dark traits. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/QmoqgLThjATbAeyQr

Althaus, D. & Tur, E. (2023). Impact obsession: Feeling like you never do enough good. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/sBJLPeYdybSCiGpGh

Baumann, T. (2017). S-risks: An introduction. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/intro

Baumann, T. (2018). A typology of s-risks. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/a-typology-of-s-risks

Baumann, T. (2019). Risk factors for s-risks. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/risk-factors-for-s-risks

Baumann, T. (2020). Common ground for longtermists. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/common-ground-for-longtermists

Baumann, T. (2022a). Avoiding the Worst: How to Prevent a Moral Catastrophe. centerforreducingsuffering.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Avoiding_The_Worst_final.pdf

Baumann, T. (2022b). Career advice for reducing suffering. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/career-advice-for-reducing-suffering

DiGiovanni, A. (2023). Beginner’s guide to reducing s-risks. longtermrisk.org/beginners-guide-to-reducing-s-risks

Knutsson, S. & Vinding, M. (2024). Introduction to suffering-focused ethics. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/introduction-to-suffering-focused-ethics

Knutsson, S. (2025). Ethical analysis of purported risks and disasters involving suffering, extinction, or a lack of positive value. Journal of Ethics and Emerging Technologies, 35(2), 1–20. jeet.ieet.org/index.php/home/article/view/163/149

Rational Animations. (2024, May 4). S-Risks: Fates Worse Than Extinction [Video]. youtube.com/watch?v=fqnJcZiDMDo

Todd, B. (2018). Doing good together: how to coordinate effectively and avoid single-player thinking. 80000hours.org/articles/coordination

Tomasik, B. (2013). Gains from Trade through Compromise. longtermrisk.org/gains-from-trade-through-compromise/

Tur, E. (2024). Navigating mental health challenges in global catastrophic risk fields. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/fzZnuGoeBKaos8pwG

Vinding, M. (2020). Why altruists should be cooperative. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/why-altruists-should-be-cooperative

Vinding, M. (2022a). Research vs. non-research work to improve the world: In defense of more research and reflection. magnusvinding.com/2022/05/09/in-defense-of-research

Vinding, M. (2022b). Popular views of population ethics imply a priority on preventing worst-case outcomes. centerforreducingsuffering.org/popular-views-of-population-ethics-imply-a-priority-on-preventing-worst-case-outcomes

Vinding, M. (2022c). Radical uncertainty about outcomes need not imply (similarly) radical uncertainty about strategies. magnusvinding.com/2022/09/07/strategic-uncertainty

Vinding, M. (2022d). Reasoned Politics. magnusvinding.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/reasoned-politics.pdf

Vinding, M. (forthcoming). Compassionate Purpose: Personal Inspiration for a Better World. magnusvinding.com/books/#compassionate-purpose

Appendix: Longer motivation table

Below is just a longer version of the table found in §3.1, as I think that all these dimensions can be practically relevant in their own ways.

Table A. Some goal dimensions, intended to illustrate the kinds of goals that might naturally motivate us (left) more than s-risk reduction (right).

| A goal can be… | ||

| 1. | Concrete (“post more of this specific content on social media”) | Abstract (“reduce uncertainty in cause prioritization”) |

| 2. | Emotionally Salient (“help a friend in need”) | Emotionally Distant (“help also less relatable, unseen minds”) |

| 3. | Completable (“solve this; get things done”) | Endless (“keep reducing the risk”) |

| 4. | Under Direct Control (“I am easily able to do this”) | Only Indirectly Influenceable (“I could maybe nudge some probabilities”) |

| 5. | Safe (“even if you fail, you’ll do no harm”) | High-Stakes (“you might have a significantly negative impact”) |

| 6. | Constructive (“build this; create that; show your progress”) | Preventive (“even if you do it right, there might be nothing to show for it”) |

| 7. | Measurable (“optimize this metric”) | Nebulous (“what? how? figure it out; poorly defined next steps”) |

| 8. | Personal (“deepen your relationships”) | Universal (“help all sentient beings”) |

| 9. | Perceived as Urgent (“survive; reduce that immediate pain”) | Perceived as Non-Urgent (“reflect on your guiding values”) |

| 10. | Fast-Feedback (“socializing; games”) | Delayed-Feedback (“improve the long-term future”) |

| 11. | Certain-Impact (“do this certainly helpful thing”) | Uncertain-Impact (“you might have no impact”) |

| 12. | Unifying (“bring people together”) | Potentially Divisive (“discuss inconvenient ideas”) |

| 13. | Simple (“follow these few steps”) | Complex (“avoid worst-case outcomes”) |

| 14. | Divided into Subgoals (“do these 100 small things”) | Perceived as a Monolith (“achieve this one huge goal”) |

Notes

- ^

For an introduction to suffering-focused ethics, see Knutsson & Vinding, 2024.

- ^

Beyond possible views, it appears that popular views in population ethics imply a strong priority on preventing outcomes with large numbers of miserable beings, as argued in Vinding, 2022b.

- ^

For an ethical analysis exploring some key tensions and overlaps between these three risk categories, perhaps see Knutsson, 2025, particularly sections 6 and 7.

- ^

For more concrete examples, see Baumann, 2020.

- ^

- ^

Baumann, 2019, “How risk factors interact”:

For instance, polarisation and conflict can increase the likelihood that a malevolent individual rises to power. A dictatorship under a malevolent leader would, in turn, likely impede efforts to prevent s-risks. Advanced technology could potentially multiply the harm caused by malevolent individuals — and so on.

Conversely, the presence of a single risk factor can, at least to some extent, be mitigated by otherwise favourable circumstances. Advanced technological capabilities are much less worrisome if there are adequate efforts to mitigate s-risks. Likewise, without advanced technological capabilities or space colonisation, the suffering caused by a malevolent dictator would at least be limited to Earth.

- ^

Thoreau, Walden, 1854. en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Walden.

- ^

Specifically, Vinding, 2022d, Chapter 9 begins:

It is difficult to assess how a given policy will affect future suffering. Evaluating policies by trying to measure their direct effects on suffering is unlikely to be the best approach, one reason being that suffering itself can be difficult to measure directly, especially on a large scale. This suggests that we should instead look at factors that are easier to measure or estimate — factors that can serve as proxies for future suffering. Ideally, we should build a framework that incorporates many such proxies; a framework with more structure than just the bare question “How does this policy influence suffering?”, and which can help us analyze policies in a more robust and systematic way.

- ^

For more on this point, see Vinding, forthcoming, §6.3.

- ^

- ^

A common saying attributed to statistician George E. P. Box. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_models_are_wrong.

- ^

- ^

- ^

Description from Vinding, 2022c. For a brief argument for cooperation, see Vinding, 2020. For a focus on politics and which policies might best promote cooperation to reduce s-risks, see Vinding, 2022d, Chapters 9–14. For more technical analyses of the value of promoting cooperation from an s-risk perspective, see Brian Tomasik’s articles on the topic, reducing-suffering.org/#cooperation_and_peace.

- ^

Baumann, 2022a, Chapter 10, “Technical measures to reduce s-risks from AI”. This has been a major focus area of the Center on Long-Term Risk (CLR), longtermrisk.org.

- ^

- ^

The following footnotes point to further reading in Vinding, forthcoming, unless otherwise noted.

- ^

Vinding, forthcoming, Chapter 1.

- ^

Chapter 10 covers some low-hanging fruit.

- ^

- ^

Chapter 3.

- ^

Chapter 4, Chapter 7.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

§6.4.

- ^

Chapter 5.

- ^

Althaus & Tur, 2023.

- ^

- ^

Chapter 6. This line is just my slight rewording of the age-old Serenity Prayer.

SummaryBot @ 2025-03-24T16:59 (+14)

Executive summary: This post argues that s-risk reduction — preventing futures with astronomical amounts of suffering — can be a widely shared moral goal, and proposes using positive, common-ground proxies to address strategic, motivational, and practical challenges in pursuing it effectively.

Key points:

- S-risk reduction is broadly valuable: While often associated with suffering-focused ethics, preventing extreme future suffering can appeal to a wide range of ethical views (consequentialist, deontological, virtue-ethical) as a way to avoid worst-case outcomes.

- Common ground and shared risk factors: Many interventions targeting s-risks also help with extinction risks or near-term suffering, especially through shared risk factors like malevolent agency, moral neglect, or escalating conflict.

- Robust worst-case safety strategy: In light of uncertainty, a practical strategy is to maintain safe distances from multiple interacting s-risk factors, akin to health strategies focused on general well-being rather than specific diseases.

- Proxies improve motivation, coordination, and measurability: Abstract, high-stakes goals like s-risk reduction can be more actionable and sustainable if translated into positive proxy goals — concrete, emotionally salient, measurable subgoals aligned with the broader aim.

- General positive proxies include: movement building, promoting cooperation and moral concern, malevolence mitigation, and worst-case AI safety — many of which have common-ground appeal.

- Personal proxies matter too: Individual development across multiple virtues and habits (e.g. purpose, compassion, self-awareness, sustainability) can support healthy, long-term engagement with s-risk reduction and other altruistic goals.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.