Strategic considerations for upcoming EU farmed animal legislation

By Neil_Dullaghan🔹 @ 2021-04-13T15:00 (+111)

Preamble

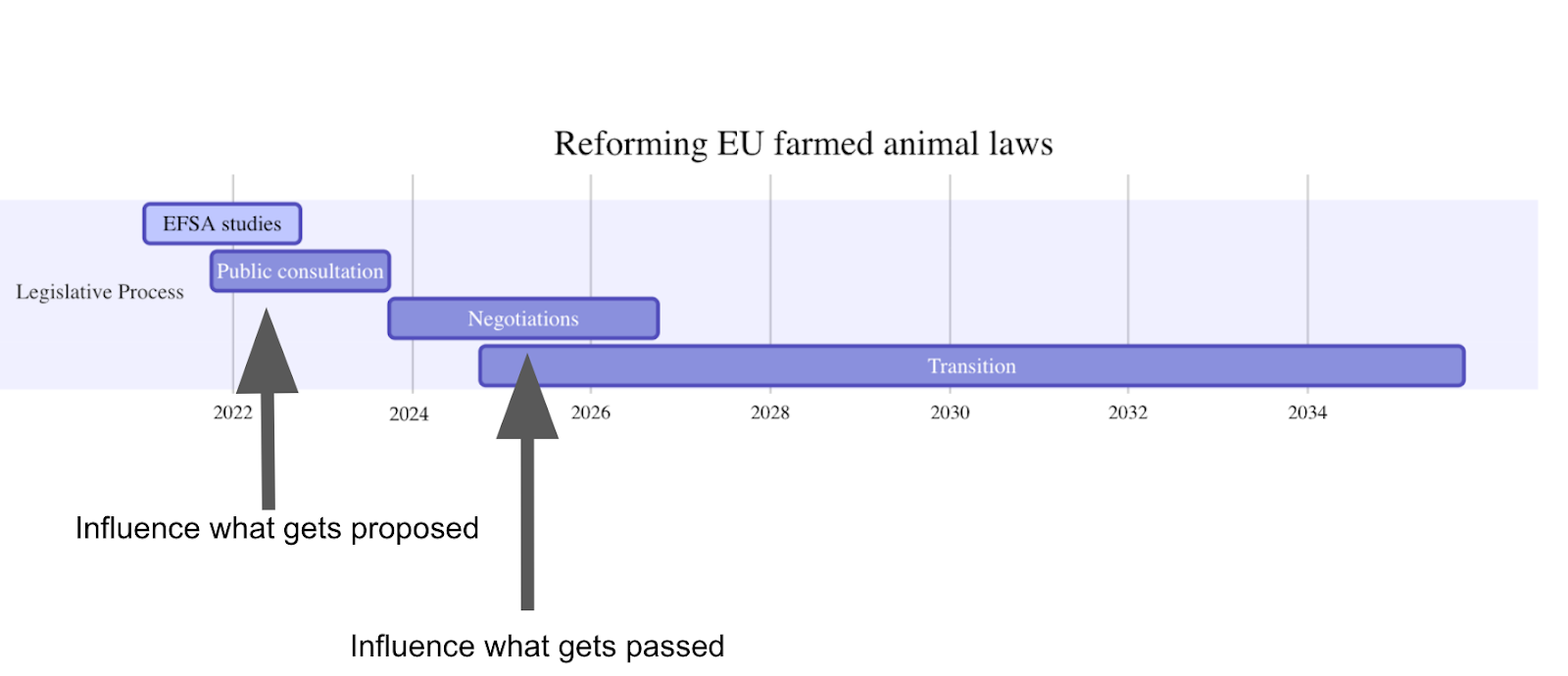

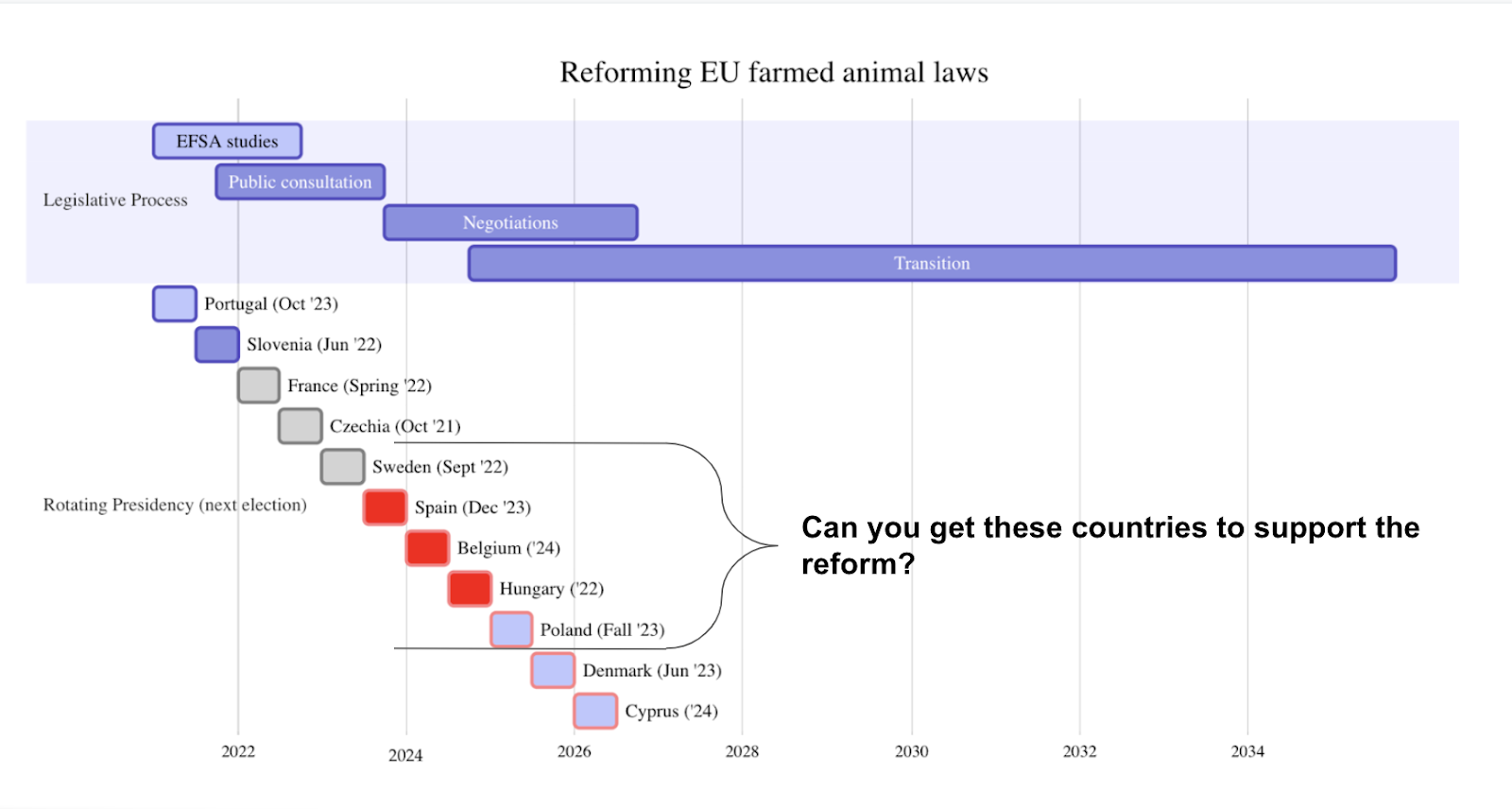

The European Commission is planning to revise and expand the scope of European Union (EU) animal protection policies with new legislative proposals in late 2023, likely followed by another ~12-24 months of negotiations before being passed into law. The effective animal advocacy movement should attempt to have the most impact during the policy formation stage and to prioritise which countries need to be targeted to ensure proposals are not significantly weakened before passing into law. I’ve recently written two reports to contribute to strategic discussions, here and here. The two reports total more than 57,000 words. Below is an overview of the project, the main recommendations, and a summary of the main arguments (or see PDF version here). For readers unfamiliar with the EU it will help to have first read the introductory post in Rethink Priorities’ EU animal policy series, read Lewis Bollard’s Open Philanthropy newsletters on EU topics (2021,2020, 2017) or watched these time stamped videos on decision-making structures in the EU (CNBC 2019, Kurzgesagt 2019).

Who is this for & what might they gain from reading this research?

- Farmed animal funders: Information on what countries one would want to see progress in to have the best chance of successful EU legislation.

- European animal advocacy organisations: Ideas on how your work can fit into a larger EU strategy, legislative texts to model your political asks on, and suggestions on why joining associations, like Eurogroup for Animals or the Open Wing Alliance, could improve your EU impact.

What did I do?

- I collected and synthesised historical case studies of six animal welfare issues (battery cages, tail docking, tethers, veal crates, sow stalls and broiler stocking density) addressed by seven EU species-specific directives[1] and progress so far towards fish welfare standards. I also offer a brief overview of animal welfare issues not yet legislated on.

- I summarised evidence from the wider political science literature on the main factors in EU decision-making, especially those highlighted by the case studies. This was to counter some of the problems of having only deeply researched cases of successful farmed animal reform. I also outline some strategic considerations for EU legislation on cage-free hens on fish welfare.

- I compiled information in Google Sheets on previous legislation, country-level statistics such as the percentage of cage-free hens, a list of animal welfare reports from the agency of the EU that provides independent scientific advice, a timeline of when countries will hold the Rotating Council Presidency, and some data from Votewatch.eu on how countries have voted on key policy areas. I hope this information can feed into an EU strategy.

- I created probability distributions of what share of egg laying hens will be cage-free by 2025, and partnered with an EU academic to generate simulations of countries voting on a hypothetical EU cage-free policy for egg-laying hens. I also posted a number of questions on the forecasting platform Metaculus as an example of one tool animal advocates can use for multi-year planning.

Why is this a worthwhile area to pursue?

- Government/policy/lobbying experience is seen as a talent bottleneck in effective animal advocacy (Harris 2021) and legislative/policy change has been less of a focus within the space relative to public opinion and industry change (Animal Charity Evaluators 2018). Relative to corporate commitments, legislative changes are likely to be much more difficult to reverse and may have higher levels of implementation due to enforcement mechanisms (though see my report on enforcement for caveats).

- As noted above, the European Commission is conducting a review of all animal welfare legislation with the aim to revise the existing legislation and expand its scope. However, the exit of the UK from the EU means the countries typically in favour of animal welfare reform have lost a major ally, so one should not assume making progress will be automatic. The Commission will open a public consultation by the fourth quarter of 2021 to revise the EU legislation on animal welfare so advocates should begin preparations now.

- Additionally, it seems possible that the Brussels effect[2] extends to animal welfare. (But I am very uncertain about the EU's international leverage regarding animal welfare and trade).

What feedback am I looking for?

- Please point out any claims or assumptions that are counterintuitive based on your experience or intuitions and why.

- Taking the assumptions on board, please point out any conclusions that run counter to those assumptions.

- If you prefer to keep your detailed feedback confidential, you can send me an email at neil@rethinkpriorities.org (or make a copy of the Google document reports and send that with your detailed comments to me).

What am I suggesting should be thought about differently than is happening now?

-

National animal advocacy organisations running corporate campaigns should either include year-targeted national and EU legislative goals in their internal strategies or coordinate with national animal advocacy organisations running legislative campaigns who do so, and be given the support to do so (in the form of funding and hiring).

-

Rather than considering political outcomes as entirely separate from corporate outcomes. There are positive feedback mechanisms between corporate campaigns and policy campaigns but I think greater coordination is needed. While many animal advocates already believe legislation is the “end goal” of corporate campaigns (see statements to this effect by Josh Balk, David Coman-Hidy, and Saulius Šimčikas), it’s unclear if the movement has answers to the key questions I outline below in “What strategies are currently being pursued?”

-

-

Members of the effective farmed animal advocacy movement should consider joining pan-European animal advocacy lobbies/associations (such as Eurogroup for Animals) and use their voice as members to move effective advocacy concerns up the list of those associations’ priorities. Associations, with consistent asks among their members, can be effective in influencing the Commission during the policy formation stage. For those organisations who find that membership costs are prohibitive, funders should consider providing them with assistance. Note that some organisations may not be allowed to join such associations if they do not meet the membership criteria, and some of the evidence in my reports suggests groups that only use direct exchanges with policymakers, but not protests, public awareness campaigns, and contacting journalists, may be better off outside of such associations.

-

Rather than defaulting to going it alone at the EU level or ignoring the EU level. It’s unclear what the “right” number of organisations in associations like Eurogroup for Animals or Open Wing Alliance should be, but at the moment there are many groups not part of these associations.

-

-

When national animal protection regulations differ across countries it has, in the past, created incentives for the producers themselves to lobby governments for harmonising EU legislation, and the Commission has justified harmonising EU farmed animal protection legislation by referring to differences between regulations among EU countries.

-

In contrast to thinking that EU legislation is only influenced by EU level lobbying (which is still important) or that progress is simply due to advances in animal welfare science.

-

-

A tension in EU animal welfare strategy is finding the right allocation of resources between areas where support for reform is easiest to generate versus areas where the opposition to reform needs to be overcome. Should the next dollar or campaign go towards the countries or institutions already making progress towards cage-free hens or towards those most likely to block or water down an EU policy on cage-free hens? I tentatively think that targeting the countries most sympathetic to farm animal reform is key to generating momentum for a proposal to be drafted, but after a proposal has been made this strategy then faces diminishing returns relative to targeting the key members of blocking minorities, which is ultimately key to a proposal turning into a law mandating improvements for farmed animals.

- In contrast to only targeting the countries most likely to be able to block reform as a last step after securing support from all the countries more predisposed to support reform, or a strategy of pursuing progress opportunistically/randomly.

-

Future effective farmed animal advocacy in Europe should factor in the timeline of countries holding the Rotating Council Presidency and should set targets to achieve in the lead up to a change in presidency, which will tend to cause that country to make more vigorous actions on animal welfare during its presidency.

- This likely suggests prioritising differently which countries need funding and when.

What concrete actions do I suggest considering?

For any desired new EU animal welfare reform (or amendment to existing legislation)

- Highlight concrete examples of current problems and potential solutions: conducting undercover investigations to shed light on the problems with existing practices through partnerships with the media, and lobbying for government and academic research into animal welfare promoting technologies.

- Reform national policy: litigation demonstrating that the current practices violate existing animal welfare legislation according to scientific data, corporate campaigns to signal to producers and politicians a shift in demand, political advocacy within a year of major corporate campaign successes (>50% of market coverage) that takes advantage of national election timetables if possible.

- Expanding the number of countries with reformed national policy: Variations in national standards have been used as a justification by the Commission for harmonising legislation. Corporate, legislative and judicial advocacy at the national level in countries making up at least a quarter of a farmed animal’s EU population, including two or three of the major producers, has been a common condition before the Commission makes proposals at the EU level to improve the lives of farm animals. This will likely be easiest in Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden given their historic support for animal protection and Germany looks to be the best candidate to take the place of the UK as a large country open to EU legislative improvements for farm animals.

- Putting animal welfare on the EU agenda: Making submissions to the Commission's public consultations, contacting your members of European Parliament, maintaining coordinated asks through EU associations and strategically targeting countries that will hold the Rotating Council Presidency by the time the first 3 conditions are met so that they prioritise the issue.

- Disrupting blocking minorities: Avoid the most likely anti-reform coalitions by targeting the lowest hanging fruit among countries that are most often parts of minimally viable blocking minorities or in “swing vote” positions: Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Belgium, Romania, Portugal, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and/or Greece.

Cage-free hens

- Political pressure to build on partial cage ban plans in Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Slovakia.

- Political pressure for initial 2030 bans in Denmark, Italy, Sweden, and Slovenia, where the market appears majority covered.

- Continue corporate campaigns in Estonia, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Romania to create political opportunities and reduce the number of possible blocking minorities.

- Advocate for Belgium, Spain, and Sweden to put cage-free reform on the agenda of their Rotating Council Presidencies 2022-2024 (Czechia has already made a request ahead of its 2022 presidency).

- Coincidentally, many of these countries are due to have general elections in the next three years: Czechia (2021), France, Slovenia, Latvia (2022), Estonia, Finland, Italy, Spain (2023). This may offer opportunities to have politicians commit ahead of negotiations.

Fish welfare

- Continued undercover investigations to bring awareness of the issue of farmed fish.

- Support fish welfare standards being included in certification schemes and animal welfare labels to facilitate changing consumer trends,[3] and corporate campaign work in Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

- Target the Rotating Council Presidencies of Denmark (2025), Greece (2027), Italy (2028), and/or the Netherlands (2029).

- Political advocacy may already be easier in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands where fish production is high and there is precedent for legislation on farmed land animal welfare.

- More pilot projects and studies of the benefits and economic viability of species-specific stunning technologies or standards, to overcome the Commission’s justifications for inaction .

Future EU research I think is promising

- Creating models of how countries will vote on hypothetical farm animal proposals that animal advocates wish to see. I partnered with an EU scholar, Prof. Marcin Kleinowski, to create such simulations using the program he developed and used in his research (2019a 2019b). I think it would be useful to incorporate data on correlations between how countries vote at the EU level, such as those from Fantini & Staal (2017) into a more sophisticated model.

- Estimating the cost-effectiveness of litigation, which appears to have been successful in Germany but I am unsure if this is or can be replicated elsewhere.

- Assess the political opportunity structures in small countries more systematically (how to arrange meetings with key political and corporate leaders, access to industry documents, direct democracy initiatives, right to petition government, salience of animal welfare among public and political parties).

- Investigate what factors created recent animal welfare progress in France specifically (professionalised animal groups, coordinated action, city level reform, political advocacy of key ministers, corporate commitments).

- Investigate what resources and tactics organisations require to carry out effective political advocacy (media contacts, targeting governing coalition partners, public opinion polls, amendments to existing laws, cooperation with environmental groups, a pragmatic approach to incremental reform).

- Investigate best practices for effective submissions of petitions, public consultations, and reports to the European Commission and European Parliament.

- Investigating whether it's possible to introduce animal welfare standards in EU free trade agreements.

Main arguments

My reports are relatively long so I have condensed some of the core arguments and insights with the most relevant supporting evidence. I expect readers to still have questions and would refer them to the longer reports or to reach out directly and I can point them to the relevant resource or provide an answer.

Cautious progress

We’re seeing positive signs that significant farm animal welfare legislation is on the EU agenda again for the first time in over a decade. As outlined in my introductory EU post, the EU announced a 10 year plan to make the food chain more sustainable (the Farm-to-Fork Strategy),[4] has completed an evaluation of its old 2012-2015 strategy on animal welfare, and is still conducting an overall “fitness check” on animal welfare legislation. EU scientific and economic studies on a cage-free transition have been commissioned, the European Parliament has stated its recommendations on a cage-free transition, major EU farmed animal groups have coordinated their asks, leading food companies are calling for an EU cage ban, and Czechia has already requested legislation on 2030 cage-free hens ahead of its 2022 Rotating Council Presidency. An early framework for fish welfare appears to have the support of at least two major producers and over a quarter of EU production. Farmed fish concerns have been raised in the European Parliament, Council and in a public consultation carried out by the Commission, and will be addressed by a Parliamentary Policy Department study on fish welfare. Commitments have been secured by advocates for the European Chicken Commitment (ECC) to improve the welfare of broiler chickens from over 220 companies. Europe’s second-largest retailer, Aldi committed to reform its broiler supply chain in Germany and Spain, and in France, a leader in weakening the 2007 EU Broiler Directive, all of the largest retailers are now pledged to the ECC (Bollard, 2020). There has also been progress on limiting male chick-culling, piglet castration, farrowing crates, and improving transport rules and animal welfare labelling. These are the type of conditions that in the past have been present before attempts at farmed animal welfare directives and offer the possibility that the two Commission administrations between now and 2029 will legislate new minimums.

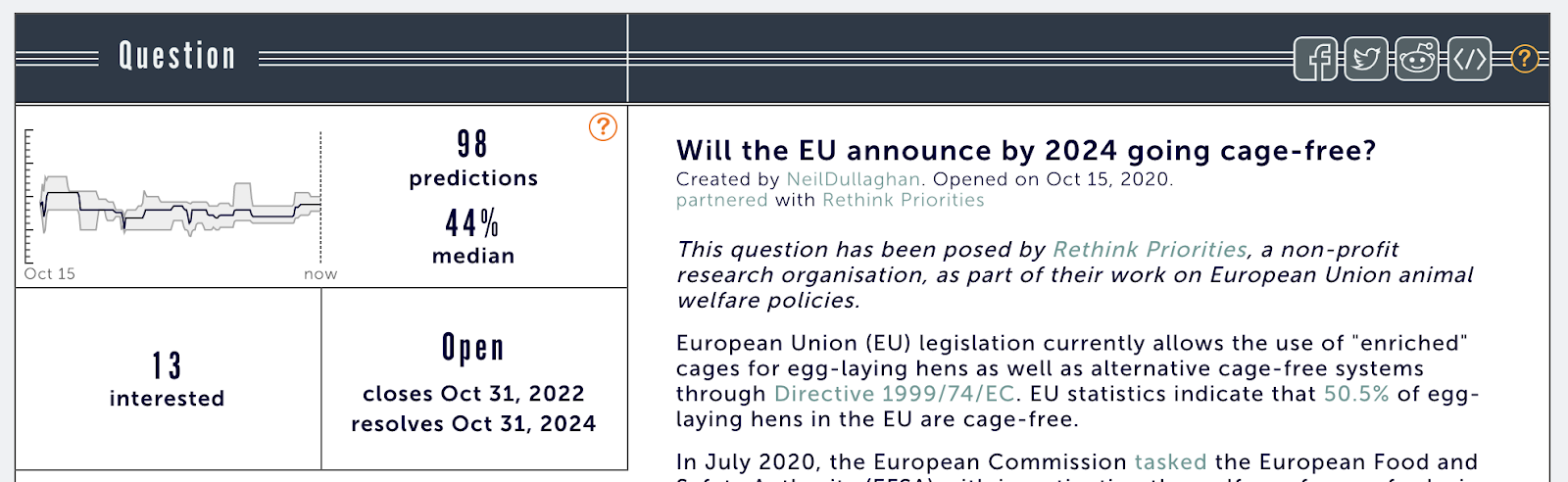

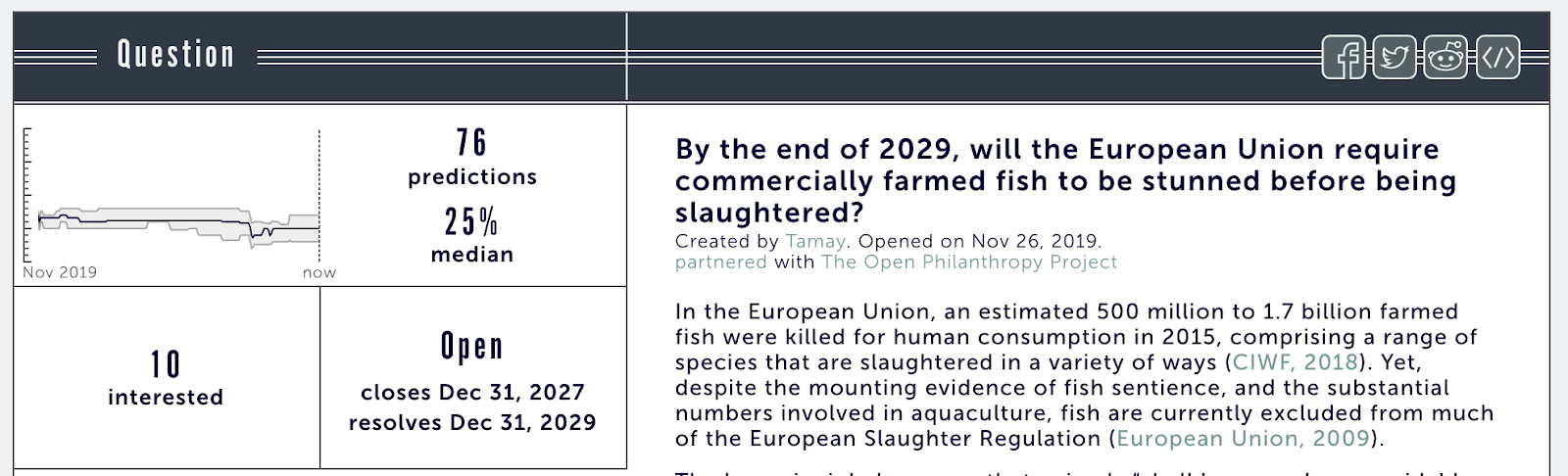

So why do we need a discussion about this approach if it seems to be working? It seems important to provide the community with evidence that an approach is working, for the purposes of replication,[5] impact assessments and to understand the theory of change. However, one should also not become complacent (I personally have found myself often so excited about progress that I forget that the base rate for success is probably very low and the movement has a long way to go before farmed animals are no longer such a pressing cause area). The Commission has an enormous laundry list of asks from stakeholders across the 27 EU countries representing 500 million people, and only a staff of 32,000 officials (EC 2020) - equivalent to the administration for a European city of 1 million people such as Cologne (Börzel & Buzogány 2019). The proposal then needs to be negotiated between national governments and the European Parliament which can take one or more years. Finally, historically reforms to housing systems have allowed for at least a 10 year transition period. As advocates themselves acknowledge, some asks will simply not be dealt with during the five year term of the current Commission, whether on cage-free standards on all animals, improvements for transport, broilers, farmed fish, or stunning and slaughter. It is important to take advantage of this current momentum, but advoctes should also be clear about what the strategy and goals are in order to see continued progress in future Commission administrations. Here I won’t deal with “longterm” in the sense of centuries or millennia, but within a reasonable period in which we could imagine the EU to continue existing and functioning much as it has for the last decade. I set up a number of questions on the forecasting platform Metaculus on EU farmed animal welfare policy to help the community look a few years ahead (see two screenshots below taken on April 7 2021 or hover over the links for the most recent forecasts):

- Will the current European Commission make a proposal before the end of its term in November 2024 to phase out remaining hen cages?

- If the EU bans caged-housing for egg-laying hens, what date will be set as the phase out deadline?.

- Will the EU have a mandatory multi-tiered animal welfare labelling scheme in place by 2025?

- When will most eggs produced in the EU be sexed before hatching?

- Will the EU phase out high-concentration CO2 stunning or killing of pigs by 2024?

- Will the EU ban mink farming in 2021?

- Will EU Member States or the Members of the European Parliament reject the ratification of EU-Mercosur agreement in 2021?

- And Open Philanthropy asked by the end of 2029, will the European Union require commercially farmed fish to be stunned before being slaughtered?

Influencing Commission proposals

As the only EU body that can initiate legislation, influencing the Commission is most important early on in the policy-making cycle, before it has handed in its proposal. After that, more emphasis can be placed on the Parliament and Council who vote on amendments and adoption. The Commission is composed of 33 Directorates General (DG) (departments with specific zones of responsibility, the equivalent of ministries at a national level). The most relevant are the DG for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTE), the DG for Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI) and the DG for Fisheries (DG MARE).[6] The Commission appears to react to public opinion (Koop et al. 2021, Rauh, 2016). There appear to be many ways for effective animal advocates to influence the Commission. Specific examples include:

- Making non-duplicate submissions in the Commission’s public consultations. Alice DiConcetto, of Animal Law Europe recently published a short manual on how to submit feedback to an EU Public Consultation that I think will be valuable for advocates. The Commission will open a public consultation by the fourth quarter of 2021 to revise the EU legislation on animal welfare so advocates should begin preparations now.

- Submitting petitions to the European Parliament seeking EU animal welfare legislation and scientific studies.

- Raising your concerns with your country’s European Parliament members who sit on the committees on agriculture (AGRI), on fisheries (PECH), and on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI).

- Using questions raised by Members of the European Parliament to sound out the position of the Commission.

- Collecting signatures for European Citizens’ Initiatives (already successful in the EndTheCageAge campaign!).

- Participation in pan-european organisations appears to increase the success of NGOs at influencing the Commission (De Bruycker & Beyers 2019, Judge & Thomson 2019, Chalmers 2018, Mahoney & Baumgartner 2015, Beyers & Braun 2014, Klüver 2013), and voicing top priority issues as members can help shape the agenda of lobbying at the EU level.

- We’ve seen evidence that corporate campaigns can turn business interests into advocates rather than adversaries at EU level (PoultryWorld 2021).

However, key decision-makers in the EU process are the representatives of national governments that sit in the Council of Ministers - a closed door institution far harder for lobbyists to access at the EU level. There might only be a narrow set of outcomes that can be achieved by EU lobbying without the support of national governments,[7] and it is the national level where many animal advocates have more direct influence, especially in Europe with so many language barriers. (I also discuss the role of the European Parliament in the full report, but many of the actions I have mentioned above apply).

The Commission is unlikely to make a proposal it believes has little chance of success (Bickerton et al. 2015) and will often respond to the requests of large countries or large alliances of countries (Fabbrini 2015 2013). One key takeaway from this research is that the variation in national laws and standards across the EU has been used as an explicit justification by the European Commission for harmonizing legislation. Across the handful of species-specific farmed animal welfare directive attempts I studied, the average was that a proposal was made when a less quarter to almost half of EU members had higher standards themselves or plausibly supported reform, including 2 to 3 of the major producers. While I found examples of national regulatory variation being associated with Commission proposals in other policy areas, the data is lacking for us to know if these figures above are a generalisable rule of thumb for EU legislation. I am not certain they provide a representative model of what the future will look like, but they provide one benchmark.

Most of the animal welfare issues addressed by EU species-specific directives I studied have been proposed by the Commission during the Rotating Council Presidency of a country with higher standards itself or that signalled willingness to support EU reform (though note the small sample size of just six directives). I also found instances of presidencies using their agenda-setting power to keep animal issues on or off the table and propose compromises. The Rotating Council Presidency operates in “Trios”: sets of fixed groups of three Member States that set a joint 18-month agenda, with each member taking six-month turns at the presidency (see illustrative example in Latvian below). The literature leans towards the idea that the position of President offers more influence than its formal powers would suggest, though there are limits (Cross & Vaznonyte 2020, Golub 2020, Van Gruisen et al. 2019, Häge 2019 2016, Alexandrova and Timmermans 2013, Warntjen 2013 2008, Kaczynski 2011, Tallberg 2010, Thomso 2008, Schalk et al. 2007, König & Proksch 2006). The presidency causes a lobbying cycle among interest groups at the European level, whereby national interest groups from the country holding the presidency temporarily become active at the EU level (Hollman & Murdoc 2018). This suggests those trying to influence EU decision-making think the presidency is an important focus too.

Influencing national standards

Pushing for higher standards in national legislation then appears a promising way to provide the Commission with the justification to propose harmonizing legislation. Negotiating positions in the Council of Ministers are shaped, in the long run, by country-specific structural factors that are relatively constant such as geography, economic structures and cultural or political traditions (Hobolt & Wratil 2020, Vaznonytė 2020, Hagemann et al. 2019, Mühlböck 2016, Bailer et al. 2015). However, there do appear to be levers that advocates can use to move animal welfare onto their agendas such as public opinion.

- Positions taken at the EU level by national governments appear to be affected by public opinion (Hagemann et al., 2017, Wratil 2017), especially in the months before national elections (Hagemann et al. 2017, Kleine & Minaudier 2017, Akexandrova et al. 2016, Bølstad 2015, Schneider 2013, Toshkov 2011).

- National animal protection policy‐making is often a reaction to changing societal demands (Vogeler 2019b, Schmidt et al. 2007) that are made salient by the work of professional animal interest groups that both criticise and collaborate with industry, and that form new coalitions around animal welfare with environmental groups and retail organizations (rather than farmers' organizations) (Vogeler et al. 2019a 2019b, Greer 2017, Tosun 2017, Ingenbeek et al. 2013). Changing consumer trends appear in many cases before national policies are reformed.

- National governments are accessible to actors able to provide information on national interests (rather than technical expertise)[8] (Bouwen 2004), such as the social and economic impact of proposed policies and the support for policies among key stakeholders and the general public (Judge & Thomson 2019).

- The uptake of animal welfare issues by political parties, junior government coalition members, and at the subnational level (cities, state governments in federal systems) has created upward pressure in the past.

- Corporate campaigns that commit a majority of the market to convert and court cases that expose violations of animal welfare acts have provided the opportunity for political advocacy to succeed nationally. However, even when the majority of a market has already converted, politicians are hesitant to impose short transition times for the few remaining producers.

- Changes in key intra-EU exporting markets also have driven changes between countries (Vogeler et al. 2019a 2019b, Ingenbleek et al. 2013 2012) but appear to only affect a small number of countries and have a mixed record.

Proposals are often watered down

“Once the Commission picks up its pen, it is likely there will be change of some kind”(Levitt et al. 2017: 41). This quote highlights how important a win it is to just have the Commission make a proposal. However, voting by national government representatives determines the final outcome and it doesn’t always pan out as advocates hope, or even match the proposal originally proposed by the European Commission.

- All but one of the animal welfare issues addressed by EU species-specific directives I looked at have been watered down, delayed, or even overridden.[9]

- In EU environmental legislation, with a larger sample size of 216 pieces of legislation, 30% of requests to water down proposals are fully successful and 45% are partially successful (Warntjen 2017). [10]

- A study of 2,200 proposals for regulations and directives that the Commission tabled between 1994 and 2016 found that more than 40% of the words in the Commission’s initial policy choices are edited during inter-institutional negotiations, and this varies significantly between the Directorates General (DG) most often proposing farmed animal reform (when proposed by DG Agriculture 70-80% remains intact versus only 45% remains intact for DG Health and Consumer Safety) (Rauh 2019).

- In all EU legislation 2000-2011, the Commission’s own priorities substantially matched the final legislative outcome in only 44% of cases, the European Parliament’s priorities were matched in 53% of cases, while the Council saw a substantial match in 62% of cases. In 33% of cases, the Commission obtained less than 50% of what it wanted (Kreppel & Oztas 2017).

Even if the Commission proposes a ban on cages or requires fish stunning, the result may skew towards some compromise such as allowing “colony cages”, limiting the cage ban to only shell egg production, or vague/de facto voluntary fish stunning criteria. Even with compromises there would often be significant improvements from the status quo, and players in this space should acknowledge the need to make pragmatic concessions. However, the examples of the broiler directive and the ban on routine tail docking of pigs in my enforcement report demonstrate how legislation can achieve very little at all when sufficiently weakened.

Blocking minorities

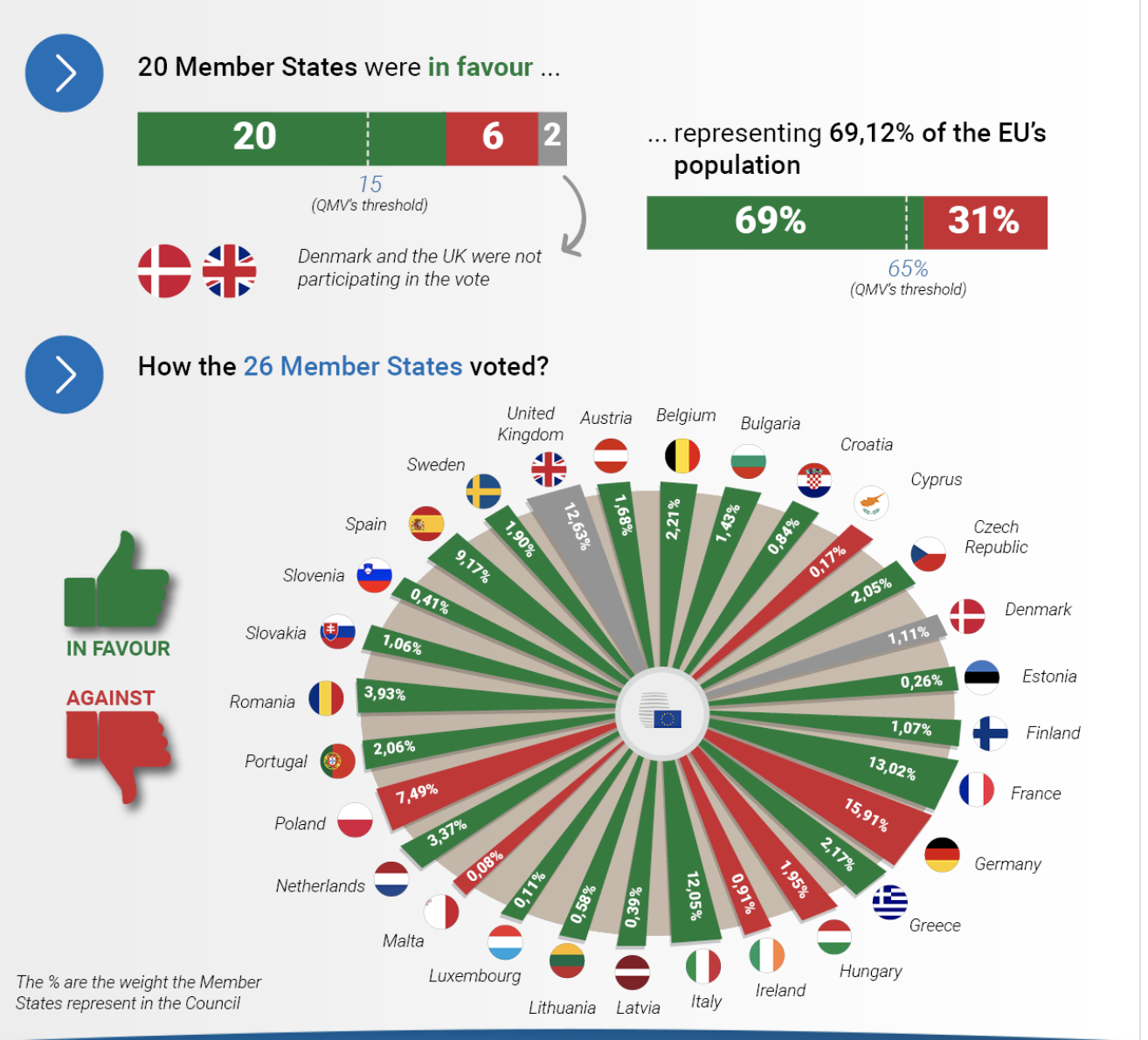

A major reason for the watering down of Commission proposals appears to be that to adopt a proposal into EU law requires a special voting majority to be reached (“qualified majority voting” or QMV).[11] Today, this requires the support of at least 55% (15/27) of countries representing 65% of the EU population,[12] but to block a proposal only requires 4 countries representing 35% (see an example from VoteWatch.eu in the image below).[13] Council negotiations involve the formation and dissolution of blocking minorities through concessions and vote exchanges until a blocking minority-proof majority is formed. In practice, actual “voting” is rare and proposals are adopted when the Presidency and the Council representatives have concluded backroom negotiations with sufficient confidence that not enough countries will object.

The only empirical study I came across found that requests to water down environmental policy proposals are 39% percentage points more likely to succeed when put forward by a blocking minority than not (76% success rate with blocking minorities versus 37% without) (Warntjen 2017). Why aren’t all blocking minority requests 100% successful? Governments do not possess perfect information regarding the voting intentions of other governments. Not all governments backing a request will be willing to veto a piece of legislation over it, so this is only a probabilistic relationship with no sharp threshold right at the number of votes necessary for a blocking minority. 70%-82% of all decisions in the Council are decided unanimously and the default is a culture of consensus even when only a qualified majority is needed (Van Gruisen et al. 2019, Häge 2012, Hayes-Renshaw et al. 2006, Sherrington 2000, Hix 1999). Blocking coalition members may be willing to accept a compromise short of what was asked or preferred by their allies in the coalition, and take that rather than rock the boat and undermine a consensus. Governments can also opt to abstain or attach dissenting declarations to supporting votes to signal dissatisfaction, short of formally voting against (though note that abstentions mean a bloc only needs 35% of voting countries). Nonetheless, how can we increase the chances that blocking minorities extracting major concessions are broken and a majority in favour of reform emerges?

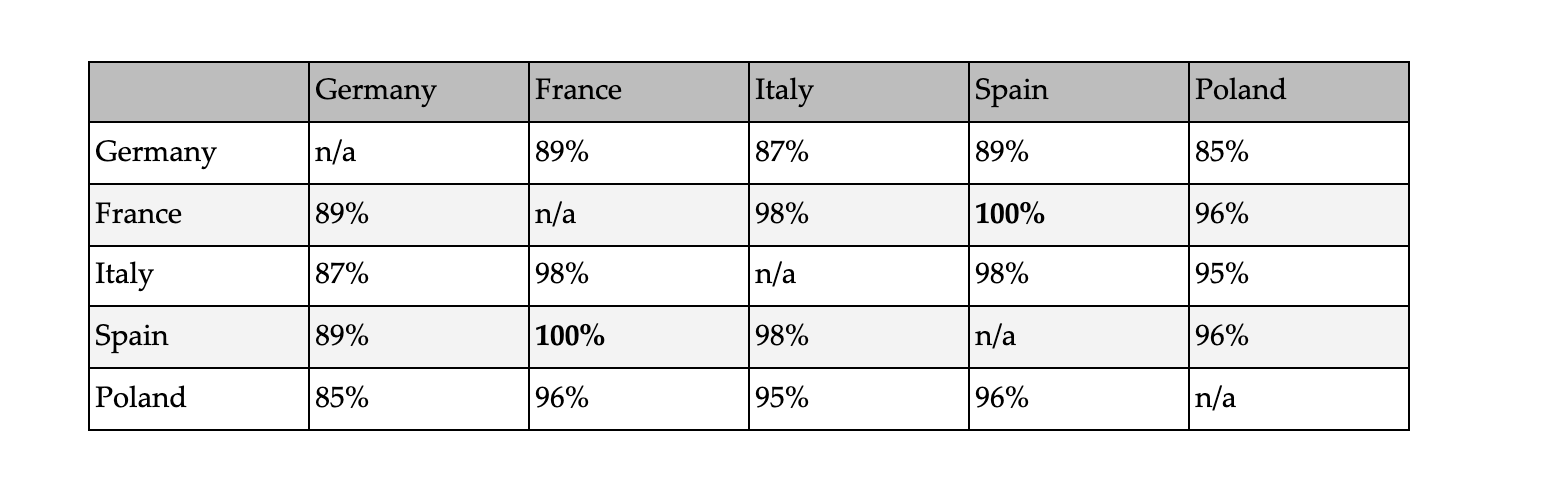

Flip the large countries

Just five (Germany, France, Italy, Poland, and Spain) of the 27 EU countries make up 65% of the EU population, and just France and Germany make up 34%. When all five agree, a proposal is almost certain to pass, and if three oppose a proposal is almost certain to fail.[14] Clearly the value of “flipping” these countries towards supporting higher welfare versions of any proposal is high. Shifting any one of these countries into a more reliable pro-animal vote would be a major achievement for the farmed animal movement. Moving the needle in each of these countries likely requires very different approaches and I provide a non-exhaustive overview of each country in the full report. For example, litigation and Green party success in subnational governments appears to have been a major unique driver of legislative progress in Germany, but this does not lend itself to countries with less professionalised judiciaries, avoidance of the issue by political parties, or unitary state structures. Even if we understood how to make progress in each of these countries, we should be sceptical that progress is possible in all of them.

The table below shows how often the final votes (not initial policy positions) of two of the largest countries matched in the field of Agriculture between 2009 and 2020, according to data purchased from VoteWatch.eu (excluding the UK). Germany is the country that votes the same as any of the other “Big 5” the least often, while France and Spain are inseparable.It could be that in every case France and Spain have backed down and voted with the majority, but the historical record on animal welfare laws suggests the opposite, so it is far more likely to be the case that France and Spain have secured the concessions they asked for. Other Votewatch.eu data shows neither France nor Spain have voted against a proposal in 56 agriculture votes between 2009-2020. Germany has voted against a proposal six times, Poland twice, and Italy once. So a baseline could be in 11%-16% of cases, large countries other than France and Spain find themselves without enough allies to block a proposal or extract concessions and still voice their dissent.

The expected value calculation of flipping enough large countries to secure a desired reform should factor in the probability that any two large countries agree, nevermind the much lower probability that all large countries enter negotiations with the same policy preference. It seems very plausible that at some point funds and talent in these large countries face diminishing returns. I don’t know where this threshold lies, but I can suggest where further resources might be spent instead for higher impact on EU reform. While pushing for reform in all the large countries it may be useful to hedge against the possibility that this effort fails in some, and consider the likely scenarios where EU success could still be achieved (especially because as I demonstrate below, even having three large countries in support still leaves many options open for the remaining two large countries to assemble an anti-reform coalition).

Population size isn't everything

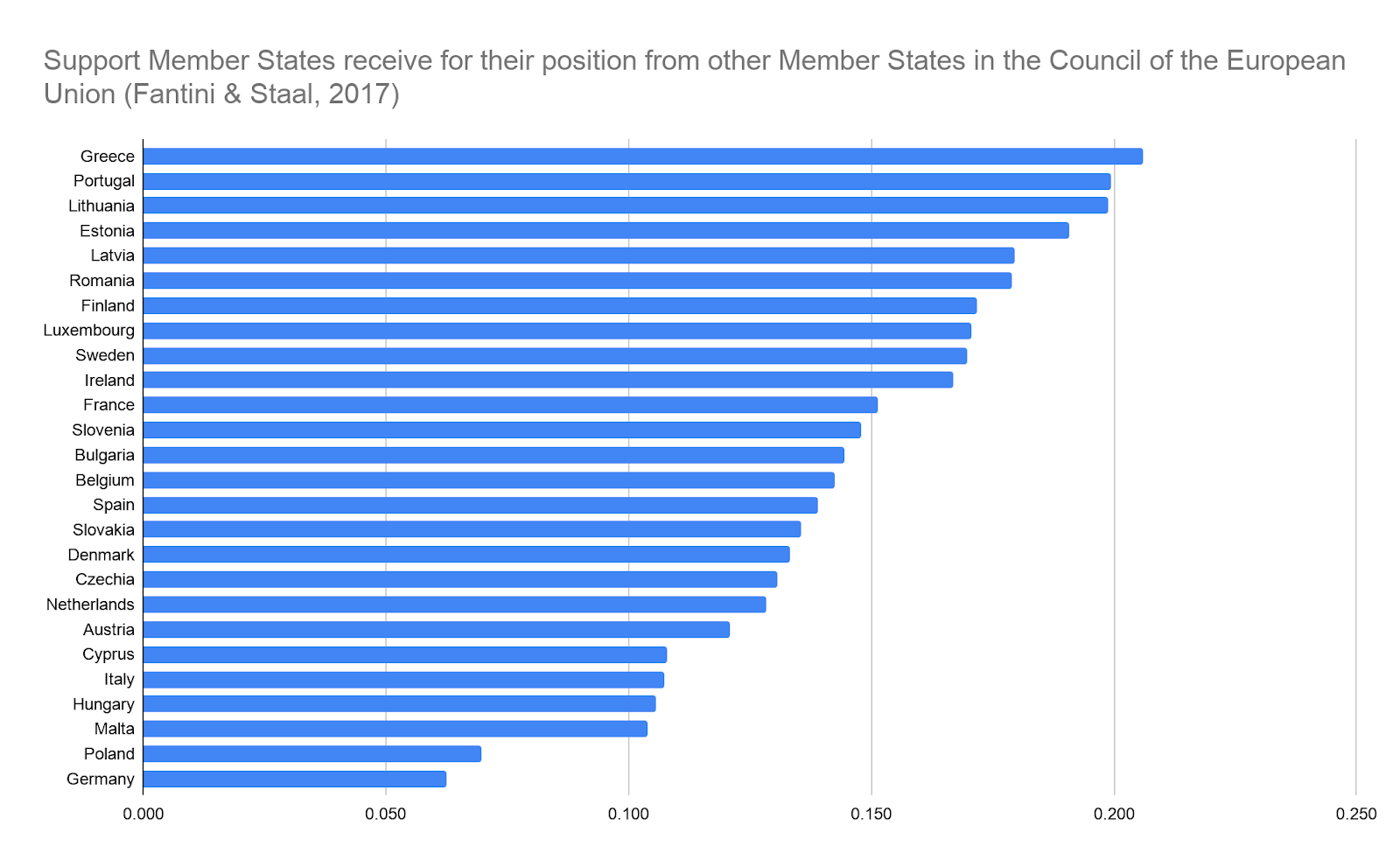

Numerous models of voting probability in the Council suggest that an index of formal voting power, the votes a country has weighted by population, is a weak predictor of bargaining success or policy outcomes. Despite a list of structural disadvantages (Panke 2010) many smaller countries are more likely to achieve outcomes closer to their ideal policy outcomes than their formal voting power would suggest, and find their preferred policies supported by more countries than even the large countries do, even on controversial issues ranked as important to those countries (Golub 2020, Lundgren et al. 2019, Wasserfallen et al. 2019, Hosli et al. 2018, Kirpsza 2018, Fantini & Staal 2017, Arregui 2016). Some smaller countries employ effective counterbalancing strategies such as creating regional alliances, focusing solely on a single issue, and using the scheduling prerogatives of the Rotating Council Presidency to ‘buy time’ to build blocking coalitions and advance private interests (Cross & Vaznonyte 2020, Van Gruisen et al. 2019, Häge 2019 2016, Kaczynski 2011, Panke 2010, Tallberg 2010). A country whose policy preferences are sufficiently close to the majority of other countries will more often be in a “swing” position to decide the final outcome of a vote compared to a country which exhibits extreme policy preferences. There is some leverage from holding centrist positions, especially if they are close to the Commission (Lundgren et al. 2019). Lithuania, Estonia, Romania, Portugal, Latvia, and Greece appear relatively more likely than other countries to see their initial policy positions supported by many countries and/or countries with large voting weights. See an example below from the work of Fantini and Staal (2017 2016).[15]

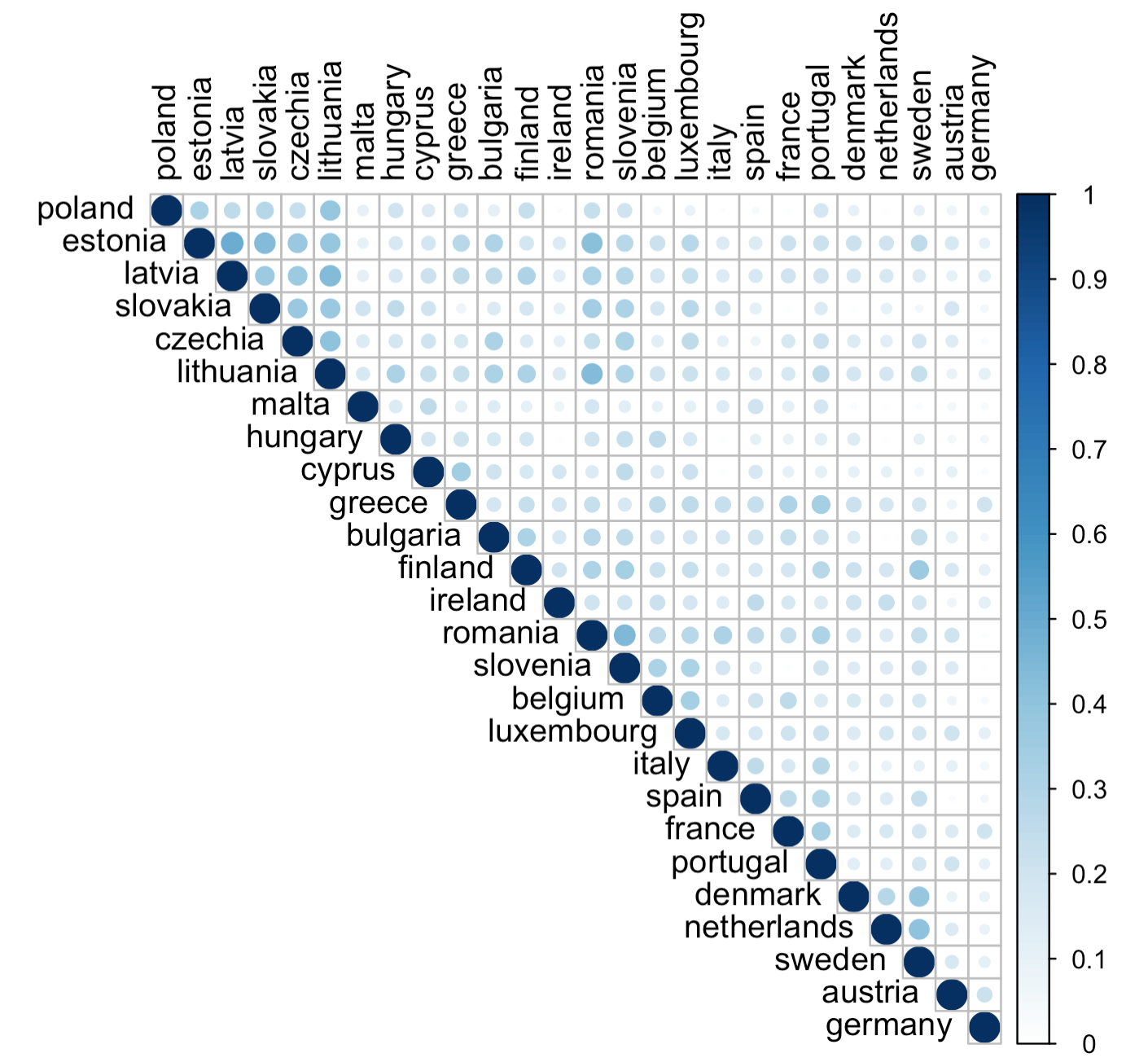

The levels of support Member States receive for their positions calculated by Fantini & Staal (2017) are the result of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient using the levels of disagreement (e.g., yes-vote, abstention, no-vote) that can be found in 1,762 votes contained in the Monthly Summary of Council Acts published by the Council Secretariat from February 2004 until December 2012. “The calculated correlation coefficients thus measure the alignment of policy preferences between Member States and can therefore be used to determine the average support a Member State gets for its position in the Council.” As it is using a non-parametric measure (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient), the measure is without unit (without parameters), and it is adjusted by voting weight (according to the authors).

A smaller country usually means a smaller bureaucracy for advocates to engage with, where it's entirely possible for an animal welfare organisation to get a meeting with the Prime Minister. There is a large literature on political opportunity structures (POS) that I did not conduct a systematic review of nor find ready made datasets to use (though see a discussion about the work of Ruedin (2011) and Vráblíková (2013) in the full report). This is an area for future research.

Coalitions

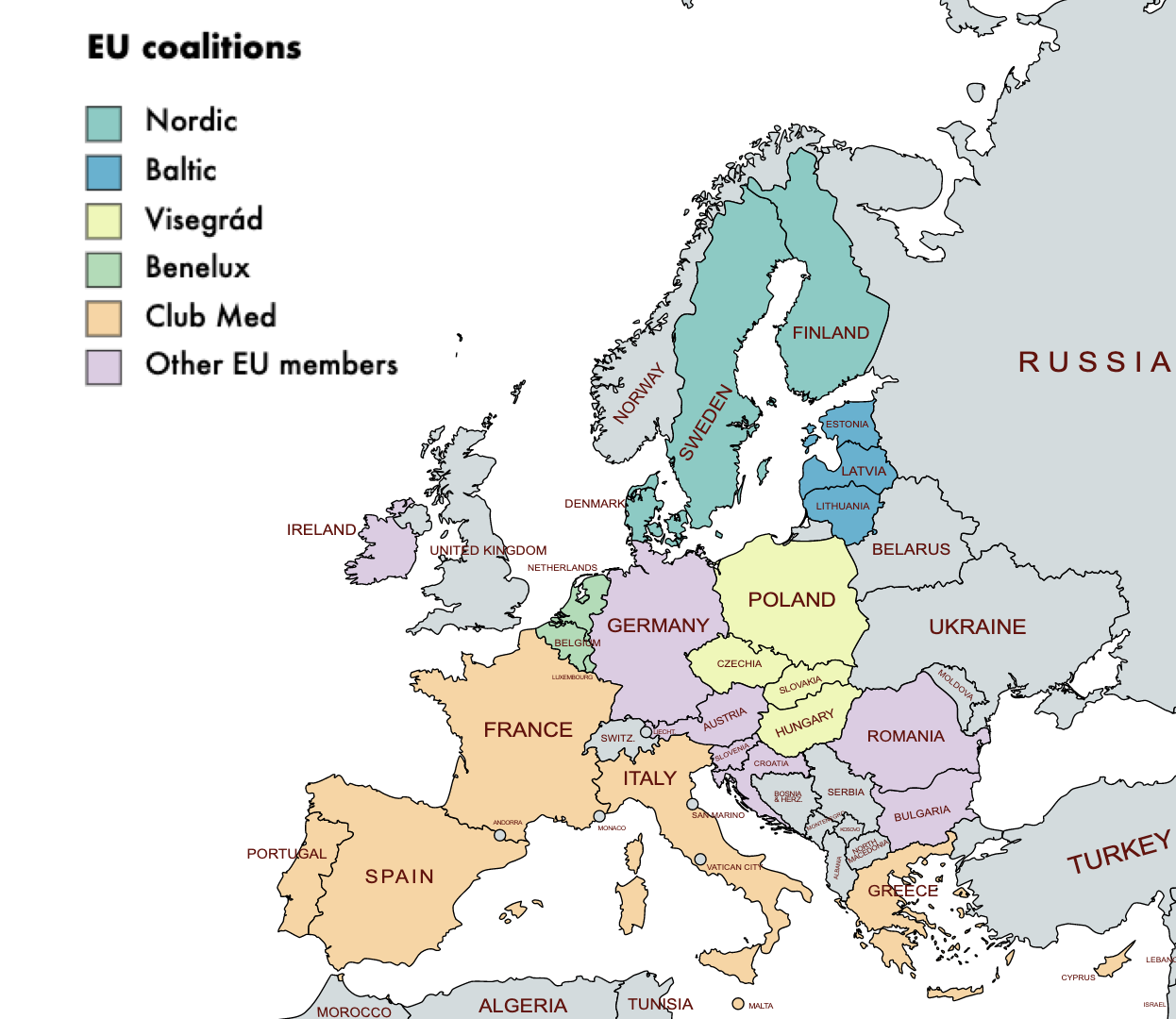

The potential blocking power of countries comes not just from their population size, but from finding allies that can create a blocking minority (Häge 2012, Dür & Mateo 2010, Novak 2010). Voting coalitions appear to coalesce in patterns (Kleinowski 2019b, Doina 2018, Fantini & Staal 2017, Frantescu 2017, Huhe et al. 2017, Mercik & Ramsey 2017). The Baltic (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), Benelux (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg), Nordic (Denmark, Sweden, Finland), and Visegrád countries (Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia) often coalesce, respectively, even forming institutions around these partnerships. The small southern states (Greece, Portugal, Malta, Cyprus) tend to vote together and with Spain or France and Italy as part of “Club Med”.

There are of course some policy-specific coalitions. There has been a coalition around animal welfare policy of Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden (and previously the UK), with support often coming from Germany and Luxembourg (note that this is based on voting patterns in the 1990s I found- but in more recent times, since 2016 there has been a "Vught alliance" on animal issues among Germany, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden). Among these are countries with the smallest share of their workforce employed in agriculture. This group has often been where early successes in farm animal welfare legislation have occurred. This makes up only six countries with 28% of the EU population however- not even enough for a pro-reform blocking minority. There may be other EU countries with conditions associated with higher support for animal welfare policies (rising rates of non-agricultural employment, urban populations, with higher per capita incomes)[16] such as Belgium, Czechia, and Malta that could become members.

Overall, the research I discuss in the report (Kleinowski 2019a 2019b, Doina 2018, Fantini & Staal 2017 2016, Frantescu 2017, Huhe et al. 2017, Mercik & Ramsey 2017) suggests France is a powerful player often able find allies in Italy, Spain, Poland and Romania, while Germany performs poorly at finding allies and is often outvoted in general. If one has no other information on the probability of country A voting in a certain way, then one could take the voting correlations between countries from Fantini and Staal (2017) (converted into the figure below) as a base for calculating a measure for support for country A’s positions. One could then use this measure as an approximation for predicting winning or blocking coalitions for country A’s position by specifying cut-off levels for this measure of support. This research points to de facto ‘allies’ in EU policy – in the sense that they tend to support the same positions,[17] and those whose interests are not aligned and tend to oppose each other’s positions. It might be possible though via corporate campaigns, litigation, and political advocacy to shift the positions of some countries and make them less reliable allies for those countries opposing reform.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients based on non-unanimous Council votes 2004-2012

Getting the groupings above to agree to a higher welfare reform, or breaking them apart are two strategies for generating a majority in the Council. If one can make progress among some key allies, then it widens the opportunity space for welfare reforms to be passed even in the likely event that attempts to all flip all the large countries fail. One concern is that some of these apparently influential smaller countries like Greece and Romania also have among the highest national shares of the workforce employed in agriculture (12.1% and 22.9% respectively). However, conditional on already having secured support from some major producers and the animal welfare bloc (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) it’s unclear what the benefit is of pouring resources instead into a more tractable country that is unlikely to shift one of these voting coalitions.

Can I make some back of the envelope expected value calculations here?

The short answer is no, I don’t have enough reliable base rate data or funding figures to generate probabilities I could be confident in. I am not interested so much in how many animals are directly affected by reform in a given country, but how the probability of success for an EU reform that covers all EU animals is affected. The key seems to be where does the next dollar or campaign in a country make the largest positive impact on the probability that the EU moves towards improved animal welfare? I could then multiply this probability by the number of animal lives that could be improved by an EU animal welfare directive. Recall the data above that suggested 40% of the Commission’s original proposal is changed on average, the final outcome matches the Commission’s priorities in 44% of cases, almost half of requests to water down environmental proposals are partially successful, and two thirds are successful when backed by a blocking minority. All this suggests our baseline that a proposal survives negotiations intact should not be especially high.

If it were the case that one needed a simple majority and all countries were weighted equally I would just move down the line of opposition securing support from each country until reaching 51% support. Due to the voting rules of the Council there may be lower returns to each additional coalition member if they were unlikely to oppose reform anyway, while a blocking minority remains. One the other hand, as the addition of multiple countries shifts the consensus position towards reform those initially opposed to reform may be forced to seek a weaker concession, even if many blocking minority options still exist.[18] It may be that making progress in countries like Romania and Greece is simply so intractable that the expected value of directly disrupting a blocking minority is lower than scoring wins in tractable countries in the hope a majority emerges.

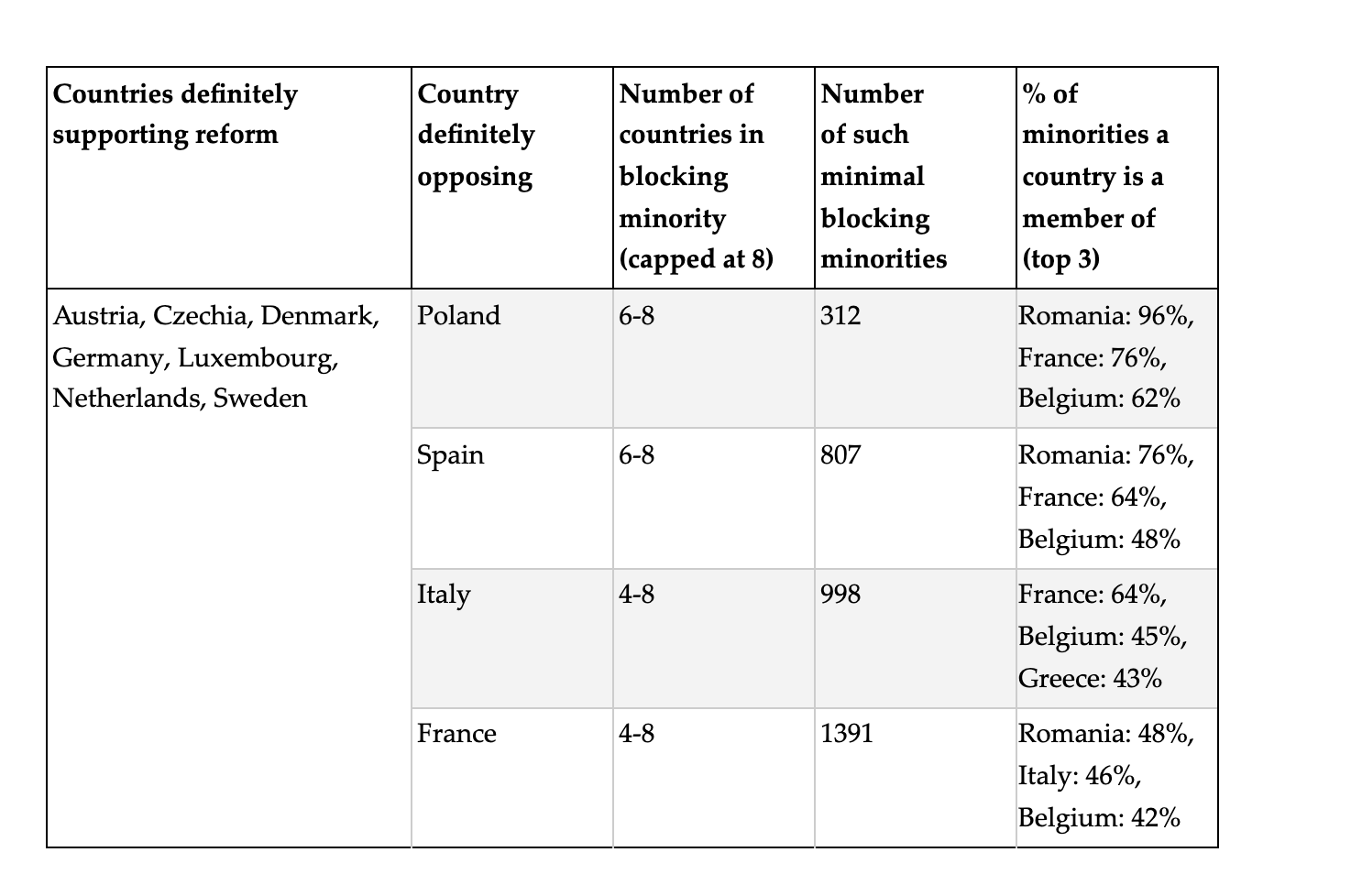

I collaborated with Prof. Marcin Kleinowski using his proprietary program POWERGEN 5.0 (a program in Excel) to generate some simulations of support for a Commission proposal banning cages for egg-laying hens.[19] The simulations assume that the countries with cage bans already (Austria, Czechia, Germany, Luxembourg) support the proposal. In the simulations described below Poland was set in definite opposition to a proposal (as this seemed very likely in practice), and simulations were run on the number of minimal blocking minorities that could be formed[20] - conditional on no more than two large countries opposing.[21] This condition is a practical reality (three large countries opposing pretty much guarantees a proposal will be blocked/overturned) and also means we must always imagine winning over at least three of Germany, Poland, Spain, France, Italy to succeed. A tall order. The number of countries in a minimal blocking minority is artificially capped at eight to be more realistic.[22]

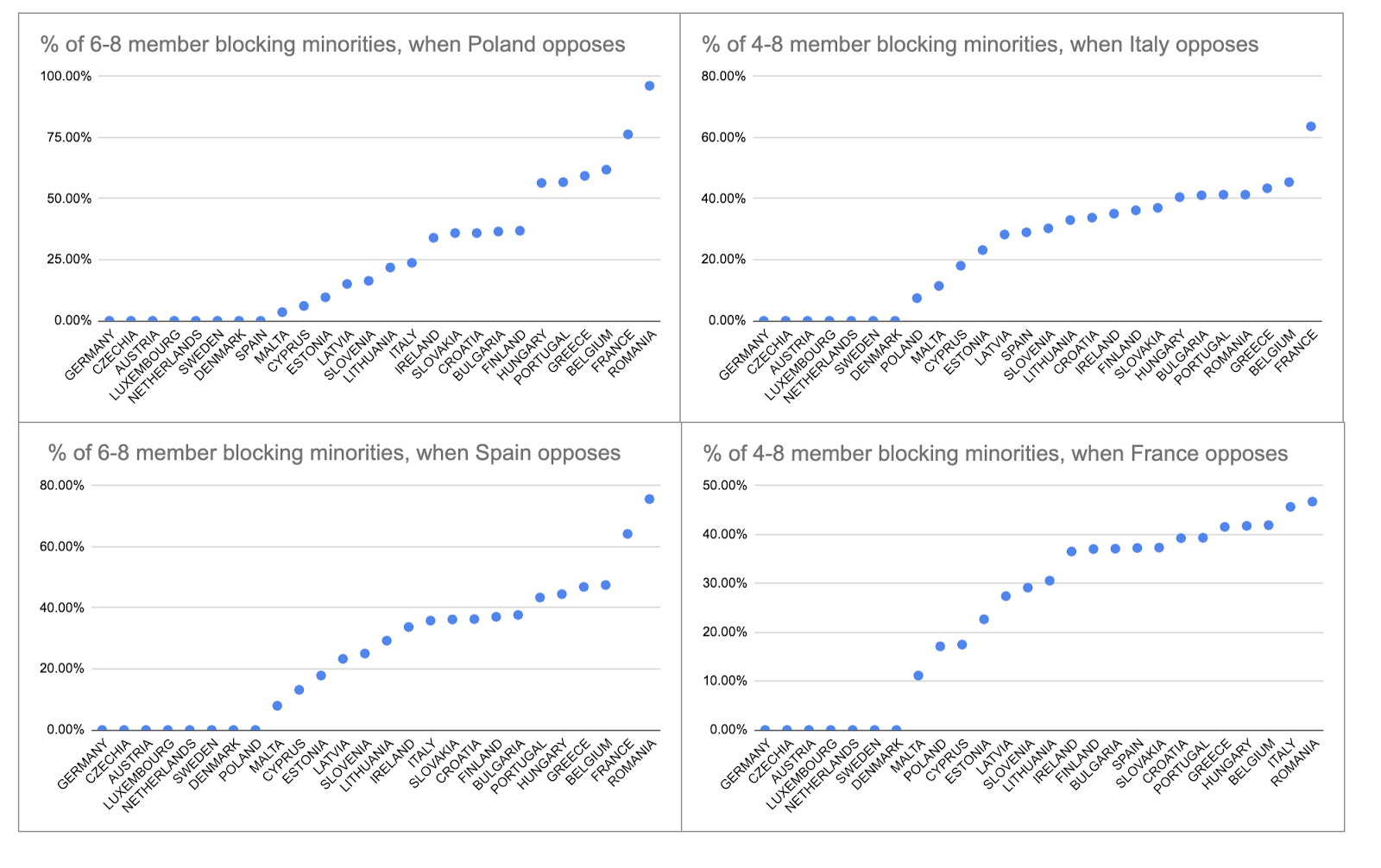

In the starting simulation with just the cage ban countries in favour of the proposal, the Netherlands could be a member of 60% of the 2,336 blocking minorities of six to eight countries that Poland can form (no four or five member minimal blocking minorities are possible in this scenario because Poland is small among the large countries). France and Romania could each be members of 64%. Italy could be a member of 32%, and Spain only 3%. Adding the other classic pro-animal welfare countries (Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden) to the pro-reform side reduces the total options to 312 minorities. I then compared adding to the reform side the seven countries with the next highest shares of cage-free hens (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Slovenia) versus adding just three countries that I initially hypothesised would be key members of blocking minorities (Portugal, Romania, Slovakia). The former reduces the number of six to eight member blocking minorities to just 18, while the latter completely removes all of the six to eight member blocking minorities. Both would be very impactful and so one needs to weigh this impact against the cost of converting one group versus the other. (We also simulated adding countries individually rather than in groups in the full report).

Setting Poland as definitely opposed was a strong assumption, so we ran simulations where the cage ban countries would be joined by the classic animal welfare bloc members (Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden) and rotated which one of the remaining four large countries is set in definite opposition to a proposal.

Simulated minimally viable blocking minorities on a EU cage-free policy, given certain assumptions

We find that there are the most minimal blocking minority options of four to eight countries available under these conditions when France definitely opposes, with 1,391 options. When Poland or Spain oppose, there are no blocking minorities of only two large countries that total four or five - each must always get the support of five to six additional countries. As France is so large it can form 25 minorities with just three to four additional countries (though always including Italy).[23] Remember that in this case it would mean that Germany, Spain, Poland and 19-20 additional countries are in favour of reform, or unwilling to vote against reform. The point of the simulation is to highlight that even after scoring victories in 20 countries (including three large countries), it would not mean a decisive victory because those opposed to reform would still have viable options - even if many countries decided to defer to the majority opinion for the sake of consensus. Adding Finland to the reform coalition is no different than adding Slovakia for example, and would still leave a Franco-Italian alliance with many options. On the other hand, securing the support of Romania would mean that Franco-Italian opposition would need to assemble larger blocking minorities to be minimally viable and have far fewer options to do so.

Plotting the percent of minimal blocking minorities each EU country could be a member of from each scenario (in the image below), there are many countries that are similarly substitutable members of blocking minorities and a small number of countries that must be part of almost all blocking minorities. It’s not simply the case that all the largest countries are the ones with most impact: when Poland opposes, Greece is a more necessary part of minimal blocking minorities than Spain. Across the scenarios, France and Romania recur as being in the vast majority of blocking minority options, and to a lesser extent Belgium and Greece - suggesting that securing their support means there are significantly fewer options available. (More simulations and their details are available in the full report).

What strategies are currently being pursued?

While Eurogroup for Animals has EU legislation as a major objective and national animal advocates aspire to such achievements, I think the effective animal advocacy movement should be developing answers to some key EU strategy questions, such as:

- Are we building strategy around which countries are holding the Rotating Council Presidency?

- Does corporate campaigning need to be done in every EU country or not?

- What's the next step once corporate campaigns reach diminishing returns: EU legislation? State-level or other local legislation?

- Are actions being taken to pave the way for those next most valuable steps?

- Who, if anyone, will coordinate submissions to the upcoming public consultation on revising all EU animal welfare legislation?

- Does the movement have the scientific, socio-economic and political arguments drafted with authoritative figures to submit them?

- Does the movement have expectations of which countries will try to water down any proposals and how to overcome that opposition?

- How much extra funding does the effective animal advocacy movement need in the next five years to carry out an effective EU legislative campaign? How short is the movement of achieving that target?

Of the total disclosed 2019/2020 animal welfare funding[24] from Open Philanthropy, the EA Animal Welfare Fund, the Effective Animal Advocacy Fund and the ACE Recommended Charity Fund that has gone towards Europe, I estimated that 60% to 80% of it has gone to Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK (no longer a member of the EU) (mostly focused on hens and broilers). Very little of this then appears to have gone towards France or Poland, and a negligible amount to smaller countries that are common members of minorities or often in swing-vote positions: Greece, Portugal, Czechia, Slovakia, Lithuania, Hungary, Romania, Estonia, Belgium. On the other hand, privately shared estimates of Open Wing Alliance’s recent granting shows most has gone to organisations in countries where animal advocacy is under-resourced and very early in its development, which tend to be smaller countries and many of the most influential blocking coalition members. Of course, this does not count undisclosed funding, and I did not find data on the overall budgets of animal welfare organisations in each country to know where funding gaps are. Funders and organisers will know this better themselves and have good reasons not to disclose the information publicly.

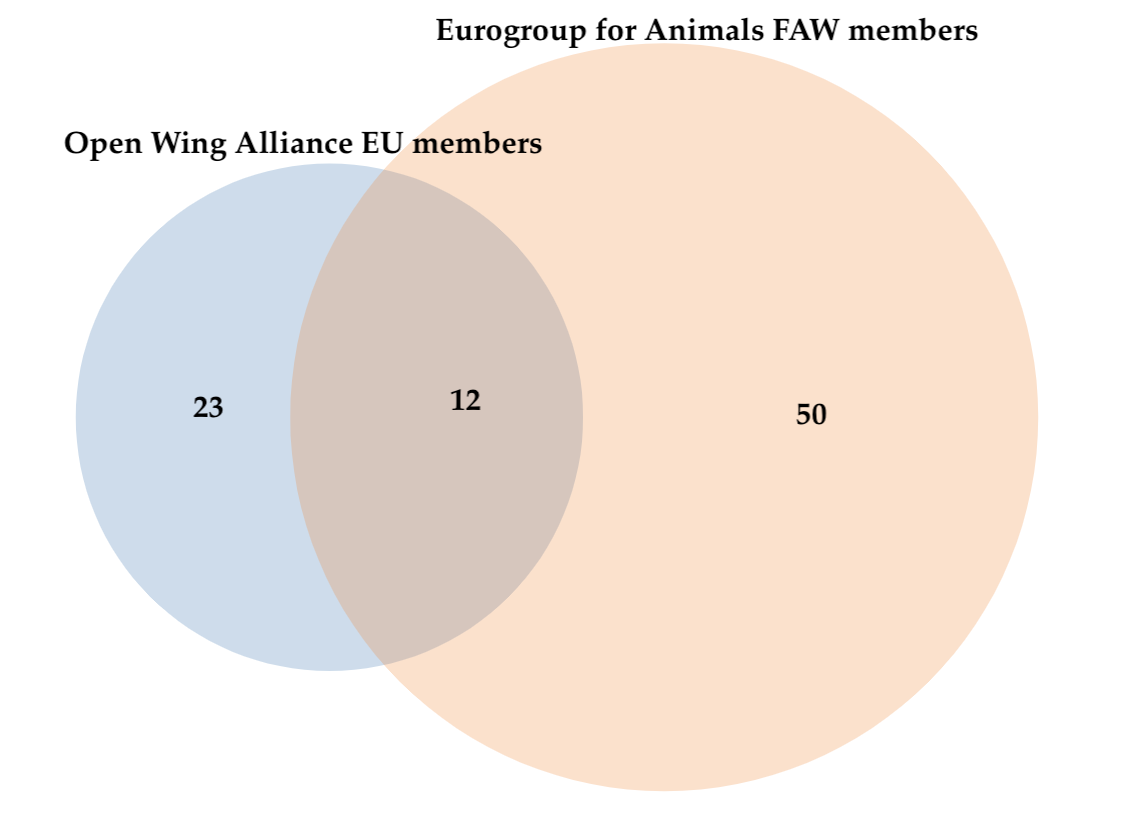

It appears that neither the Open Wing Alliance nor Eurogroup for Animals have members in Cyprus and Slovenia, and the Open Wing Alliance also doesn't have members in Hungary, Ireland and Luxembourg. A quick look through both organisations’ EU membership showed some overlap (see venn diagram below), but also a significant number of organisations that are only members of one association (note that I included any Eurogroup members that plausibly worked on farmed animals like hens, and some members like CIWF and Four Paws have multiple country branches, which both inflate the Eurogroup total).

It’s unclear if national organisations have the funding, personnel, or administrative capacity to incorporate EU legislative considerations into their strategies and prioritisation. A survey I conducted of 17 OWA members representing organisations in 10 EU countries suggested they were split more or less evenly between staffs with 10 or more full time equivalent paid employees (FTEs) and 1-5 FTEs. 7/13 (54%) had clear national legislative goals with target years but many were aiming for transition periods far shorter than have been successful in the past, or planning to only begin work in a few years, pushing likely transition periods out beyond 2030. Having clear legislative goals was more common among groups that were part of the Eurogroup for Animals umbrella than not, but the sample was too small to make a strong inference here. The Aquatic Animal Alliance has recently been formed and it’s unclear what approach, if any, it will take to EU fish welfare legislation and I hope this research can contribute to relevant discussions.

It’s unclear what share of producers need to be reformed or pledged to reform for politicians to vote for animal welfare reform. 11/15 (73%) respondents stated that 50% or more of the national market needs to be covered by corporate commitments before pushing for national legislation, and 46% stated that 70% or more of the national market needs to be covered (excluding 11% “Don’t Knows”). I’ve founded cases of reform opposed by governments even in countries with 80% of hens out of cages already, but also reform accepted in countries with less than a quarter of hens cage-free but between 45%-60% of production covered by corporate pledges. I think “momentum”, perhaps measured by the rate of recent change in production leading up to elections, is a crucial consideration as well as the effectiveness of a relatively short political advocacy campaign (1-2 years).

What are some limitations to this research?

- I draw upon the species-specific EU animal welfare directives for lessons learned with the caveat that the majority of these laws were created in the 1980s and 1990s when the EU membership and structure was very different than today. Where possible I have also drawn on the wider EU literature for appropriate baselines. Many of the votes for these laws were not publicly available and had to be inferred based on media reports, aggregate voting patterns, and basic retrospective voting models.

- For the benefit of clarity and space, this research makes some simplifications of the EU decision-making system, but I am happy to engage with EU experts on any nuances omitted that appear decision-relevant, and refer readers to my introductory post for a primer on the topic.

- This research is mainly based on directives. I focused on directives since those make up the bulk of EU legislation and the bulk of farmed animal protection legislation. These are just one legal instrument available at the EU level. Arguably I should also be considering other tools such as regulations, subsidies, research funding, method of production labels or inventing new instruments that dynamically combine legally enforceable standards and new developments in animal welfare science without requiring a political agreement to be secured each time.

- I am unsure whether animal welfare science is an important lever. I don’t know of examples of EU reform that occurred in the absence of some scientific evidence supporting a reform. However, I’ve also found many cases where animal welfare science is simply ignored. Similarly, it seems securing funding from academics and governments to test innovative technologies that improve animal lives has been important, but I am unsure how to practically go about this and whether this might entrench factory farming.

Credits

This research is a project of Rethink Priorities. It was written by Neil Dullaghan. Thanks to Daniela R. Waldhorn, David Moss, David Rhys Bernard, Marcus A. Davis, Michael Aird, Peter Hurford, and Saulius Šimčikas for helpful feedback throughout. Also thanks to Compassion in World Farming, Eurogroup for Animals, and the Open Wing Alliance who I engaged with early on in the project to get initial insights from. If you like our work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can see more of our work here.

Works Cited

Alexandrova, P., & Timmermans, A. (2013). National interest versus the common good: The Presidency in European Council agenda setting. European Journal of Political Research, 52(3), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02074.x

Animal Charity Evaluators. (2018). Allocation of Movement Resources. ACE Blog. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/other-topics/allocation-of-movement-resources/

Appleby, M. (2003). The EU Ban on Battery Cages: History and Prospects.

Arregui, J. (2016). Determinants of Bargaining Satisfaction Across Policy Domains in the European Union Council of Ministers. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(5), 1105–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12355

Bailer, S., Mattila, M., & Schneider, G. (2015). Money Makes the EU Go Round: The Objective Foundations of Conflict in the Council of Ministers. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(3), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12194

Beyers, J., & Braun, C. (2014). Ties that count: Explaining interest group access to policymakers. Journal of Public Policy, 34(1), 93–121.

Bitonti, A., & Harris, P. (Eds.). (2017). Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55256-3

Bollard, L. (2017). Why Did the EU Lead on Animal Welfare & How Can It Lead Again? Open Philanthropy. https://us14.campaign-archive.com/?u=66df320da8400b581cbc1b539&id=cba67f210d

Bollard, L. (2020). Political Opportunities in Europe. Open Philanthropy. https://us14.campaign-archive.com/?u=66df320da8400b581cbc1b539&id=9345813301

Börzel, T. A., & Buzogány, A. (2019). Compliance with EU environmental law. The iceberg is melting. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549772

Bouwen, P. (2004). Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 43(3), 337–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00157.x

Bruycker, I. D., & Beyers, J. (2019). Lobbying strategies and success: Inside and outside lobbying in European Union legislative politics. European Political Science Review, 11(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000218

Chalmers, A. W. (2020). Unity and conflict: Explaining financial industry lobbying success in European Union public consultations. Regulation & Governance, 14(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12231

CNBC. (2019). How does the EU work? | CNBC Explains. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9eufLQ3sew0&t=100s&ab_channel=CNBCInternational

Cross, J. P., & Vaznonytė, A. (2020). Can we do what we say we will do? Issue salience, government effectiveness, and the legislative efficiency of Council Presidencies. European Union Politics, 21(4), 657–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520950829

Doina, G. (2018). Coalition of states for influence in the European Council. Brexit—A step towards decisional balance in the European Council? Open Political Science, 1(1), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2018-0009

EC. (2020). Key figures on European Commission staff. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/about-european-commission/organisational-structure/commission-staff_en

Fantini, M., & Staal, K. (2016). Alliance-Building to Influence the EU: Measuring the Geography of Mutual Support (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2828116). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2828116

Fantini, M., & Staal, K. (2018). Influence in the EU: Measuring Mutual Support. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(2), 212–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12586

Golub, J. (2020). Power in the European Union: An evolutionary computing approach. Journal of European Integration, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1835886

Greer, A. (2017). Post-exceptional politics in agriculture: An examination of the 2013 CAP reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1585–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334080

Gruisen, P. van, Vangerven, P., & Crombez, C. (2019). Voting Behavior in the Council of the European Union: The Effect of the Trio Presidency. Political Science Research and Methods, 7(3), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2017.10

Häge, F. M. (2013). Coalition Building and Consensus in the Council of the European Union. British Journal of Political Science, 43(3), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000439

Häge, F. M. (2017). The scheduling power of the EU Council Presidency. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(5), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1158203

Häge, F. M. (2019). The presidency of the council of the European Union. https://ulir.ul.ie/handle/10344/8263

Hagemann, S., Bailer, S., & Herzog, A. (2019). Signals to Their Parliaments? Governments’ Use of Votes and Policy Statements in the EU Council. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12844

Harris, J. (2021). Effective animal advocacy bottlenecks surveys—EA Forum. EA Forum. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/PSZwciNjojHFAvyLq/effective-animal-advocacy-bottlenecks-surveys#The_importance_of_different_talent_bottlenecks

Hayes‐Renshaw, F., Aken, W. V., & Wallace, H. (2006). When and Why the EU Council of Ministers Votes Explicitly*. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(1), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00618.x

Hix, S. (1999). The Political System of the European Union. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Hobolt, S. B., & Wratil, C. (2020). Contestation and responsiveness in EU Council deliberations. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712454

Hollman, M., & Murdoch, Z. (2018). Lobbying cycles in Brussels: Evidence from the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union. European Union Politics, 19(4), 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518796306

Hosli, M. O., Plechanovová, B., & Kaniovski, S. (2018). Vote Probabilities, Thresholds and Actor Preferences: Decision Capacity and the Council of the European Union. Homo Oeconomicus, 35(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41412-018-0065-8

Ingenbleek, P. T. M., Harvey, D., Ilieski, V., Immink, V. M., de Roest, K., & Schmid, O. (2013). The European Market for Animal-Friendly Products in a Societal Context. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 3(3), 808–829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani3030808

Ingenbleek, P. T. M., Immink, V. M., Spoolder, H. A. M., Bokma, M. H., & Keeling, L. J. (2012). EU animal welfare policy: Developing a comprehensive policy framework. Food Policy, 37(6), 690–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.07.001

Judge, A., & Thomson, R. (2019). The responsiveness of legislative actors to stakeholders’ demands in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(5), 676–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1489878

Kaczyński, P. M. (2011). How to Assess a Rotating Presidency of the Council Under the Lisbon Rules (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1756821). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1756821

Kirpsza, A. (2018). Friends or Foes? The Effect of Forming a Coalition Between Poland and Germany on Their Bargaining Success in EU Legislative Decision-Making. ECPR General Conference Universität Hamburg, Hamburg. Retrieved 7 April 2021, from https://ecpr.eu/Events/Event/PaperDetails/40562

Kleinowski, M. (2019a). Poland’s ability to build blocking coalitions after Brexit. Politeja, 63, 43–64.

Kleinowski, M. (2019b). The impact of Brexit on the member states’ ability to build blocking coalitions in the Council. Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne, 2, 5–27.

Klüver, H. (2013). Lobbying in the European Union: Interest Groups, Lobbying Coalitions, and Policy Change. In Lobbying in the European Union. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 April 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199657445.001.0001/acprof-9780199657445

König, T., & Proksch, S.-O. (2006). Exchanging and voting in the Council: Endogenizing the spatial model of legislative politics. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(5), 647–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600808394

Kreppel, A., & Oztas, B. (2017). Leading the Band or Just Playing the Tune? Reassessing the Agenda-Setting Powers of the European Commission. Comparative Political Studies, 50(8), 1118–1150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016666839

Kurzgesagt. (2019). Is the EU Democratic? Does Your Vote Matter? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h4Uu5eyN6VU

Mahoney, C., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2015). Partners in Advocacy: Lobbyists and Government Officials in Washington. The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1086/678389

Mohorčich, J. (2018). What can the adoption of GM foods teach us about the adoption of other food technologies? Sentience Institute. https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/gm-foods

Mühlböck, M. (2017). Voting in EU Decision-Making. In M. Mühlböck (Ed.), Voting Unity of National Parties in Bicameral EU Decision-Making: Speaking with One Voice? (pp. 27–51). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39465-7_2

Novak, S. (2010). Decision rules, social norms and the expression of disagreement: The case of qualified-majority voting in the Council of the European Union. Social Science Information, 49(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018409354473

Panke, D. (2010). Small states in the European Union: Structural disadvantages in EU policy-making and counter-strategies. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(6), 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2010.486980

PoultryWorld. (2021). Food companies ask EU Commission to phase out enriched cages. Health. https://www.poultryworld.net/Health/Articles/2021/4/Food-companies-ask-EU-Commission-to-phase-out-enriched-cages-728719E/

Rauh, C. (2021). One agenda-setter or many? The varying success of policy initiatives by individual Directorates-General of the European Commission 1994–2016. European Union Politics, 22(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520961467

Ruedin, D. (2011). Indicators of the Political Opportunity Structure (POS) (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1990184). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1990184

Sandilands, V., & Hocking, P. M. (2012). Alternative Systems for Poultry: Health, Welfare and Productivity. CABI.

Schalk, J., Torenvlied, R., Weesie, J., & Stokman, F. (2007). The Power of the Presidency in EU Council Decision-making. European Union Politics, 8(2), 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116507076431

Schmidt, M. G., Ostheim, T., Siegel, N. A., & Zohlnhöfer, R. (Eds.). (2007). The welfare state, Original text: An introduction to historical and international comparison. VS publishing house for social sciences. https://www.springer.com/de/book/9783531151984

Sherrington, P. (2000). Council of Ministers: Political Authority in the European Union. A&C Black.

Tallberg, J. (2010). The Power of the Chair: Formal Leadership in International Cooperation. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 241–265.

Thomson, R. (2008). The Council Presidency in the European Union: Responsibility with Power*. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 46(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.00793.x

Thomson, R. (2011). Resolving Controversy in the European Union: Legislative Decision-Making before and after Enlargement. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139005357

Thomson, R., Arregui, J., Leuffen, D., Costello, R., Cross, J., Hertz, R., & Jensen, T. (2012). A new dataset on decision-making in the European Union before and after the 2004 and 2007 enlargements (DEUII). Journal of European Public Policy, 19(4), 604–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.662028

Tosun, J. (2017). Party support for post-exceptionalism in agri-food politics and policy: Germany and the United Kingdom compared. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1623–1640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334083

Vaznonytė, A. (2020). The rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU – Still an agenda-setter? European Union Politics, 21(3), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520916557

Vogeler, C. S. (2019a). Market-Based Governance in Farm Animal Welfare—A Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Policies in Germany and France. Animals, 9(5), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050267

Vogeler, C. S. (2019b). Why Do Farm Animal Welfare Regulations Vary Between EU Member States? A Comparative Analysis of Societal and Party Political Determinants in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(2), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12794

Vráblíková, K. (2014). How Context Matters? Mobilization, Political Opportunity Structures, and Nonelectoral Political Participation in Old and New Democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 47(2), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013488538

Warntjen, A. (2008). The Council Presidency: Power Broker or Burden? An Empirical Analysis. European Union Politics, 9(3), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116508093487

Warntjen, A. (2013). Overcoming Gridlock: The Council Presidency, Legislative Activity and Issue De-Coupling in the Area of Occupational Health and Safety Regulation. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 9(1), 39–59.

Wasserfallen, F., Leuffen, D., Kudrna, Z., & Degner, H. (2019). Analysing European Union decision-making during the Eurozone crisis with new data. European Union Politics, 20(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518814954

Wratil, C. (2018). Modes of government responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from Council negotiation positions. European Union Politics, 19(1), 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517735599

Notes

Directives are a type of EU law that define goals that have to be incorporated into the national law of countries in the EU within a certain time period but allow some flexibility for countries to apply rules to achieve these goals, and to set stricter standards if they wish. Regulations are binding rules with immediate direct effect in member states and therefore are much stronger instruments but do not allow flexibility to accommodate different legal systems across the 27 EU countries. As the only institution in the EU that can formally initiate legislation, it is up to the European Commission to launch a directive or regulation. Proposals move back and forth through the other institutions of the EU for amendments and votes and may eventually be passed into law. ↩︎

The process of unilateral regulatory globalisation caused by the EU de facto (but not necessarily de jure) externalising its laws outside its borders through market mechanisms. For example, Norway isn’t part of the EU but often has to abide by EU laws to gain access to the market, which could be influential for Norway's 850 million farmed finfish. ↩︎

Labelling of eggs seems to have been an important facilitator in shifting consumer purchasing, that also contributed to legislative change. However, see some of the risks of certification schemes in Harris (2021). ↩︎

The Farm to Fork Strategy is a new comprehensive 10-year plan that proposes measures and targets for each stage of the food chain, from production to distribution to consumption, in order to make European food systems more sustainable through investments in research, innovation, advisory services, data, skills, and knowledge sharing. The strategy states “The Commission will revise the animal welfare legislation, including on animal transport and the slaughter of animals, to align it with the latest scientific evidence, broaden its scope, make it easier to enforce and ultimately ensure a higher level of animal welfare”. However, the final text dropped a proposed end to promotional measures for meat and instead says only that the Commission will undertake a review of EU promotional support for agrifood products. The new Common Agricultural Policy will likely continue to fund intensive animal farms, which is disappointing for animal welfare but not new. Thanks to Daniela R. Waldhorn for this point. ↩︎

In many ways the cage-free progress mirrors anti-GMO campaigns of the 1990s (Mohorčich 2018), suggesting it is a model with some generalisability. ↩︎

DG for Research and Innovation might also be relevant for commissioning new animal welfare research or work on protein alternatives. ↩︎

For example, the current proposal to allow the use of insects as feed for farmed animals seems mainly to be driven by the concerted lobbying efforts of one group in the absence of any domestic opposition among EU countries, although private industry in France and the Netherlands may also have led their governments to support the move. ↩︎

This is because the Council, in its many different sections, has their national governments and ministries that come with their own officials and experts. ↩︎

The outlier was the second attempt at an EU phase out of narrow crates for veals which was expedited and given a shorter transition time in part due to advocacy by the UK government. ↩︎

Most of the individual requests by member states are for lower standards (44.1%), requests for derogations (28.2%) and extensions (27.7%) are made less often. Requests for extensions are less common, but are considerably more often successful than requests for derogations or lower standards when considering partial success. ↩︎

This applies to the EU's internal policies and actions, for example, agriculture and fisheries, internal market, border controls, economic and monetary policy, provided they do not extend the EU's competences. These decisions were typically decided by a unanimity rule but the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, increased the number of areas where qualified majority voting in the Council applies. A limited number of policies judged to be sensitive remain subject to unanimity voting: taxation, social security or social protection, the accession of new countries to the EU, foreign and common defence policy and operational police cooperation between EU countries. Insofar as I can see, animal health and welfare issues are decided formally by qualified majority votes. ↩︎

It should be noted that in special cases 72% of the countries must be in favour, but this variant is not considered here. ↩︎

The EU population number is construed de facto as the number of residents each year, provided in January by Eurostat for all member states. When designing the system, it was not anticipated that the UK, one of the largest members, would leave the EU. Also note that according to Eurostat estimates, by 2035 the population of Poland will have decreased by 1.4 million, and that of the Visegrád Group (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia) by 1.5 million. At the same time, the populations of France and Germany will have increased by 4.8 million and 2.1 million, respectively. By 2035, the population in the so-called “old” member states, which became EU members in the 20th century, is to increase by 12.4 million, while in the “new” EU countries it is to decrease by 5.6 million. Thanks to Marcus A. Davis for suggesting looking at future population trends. ↩︎

It is very unlikely that three large EU countries would be forced to build a blocking minority in the Council. Since the entry into force of the new voting rules under the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, there has been no case of a legislative initiative in which three large EU countries would be forced to form a blocking coalition. Being aware of the difficulties this would mean for a planned initiative, the Commission would rather take into account the interests of the largest countries in its proposal, or would give up putting forward the initiative, at least at a given time. ↩︎

Future research might include some heterogeneity analysis here and see what this looks like just for animal welfare votes (or just environmental votes or some similar proxy if there aren't enough animal welfare votes to be precise). Germany may take a hit on this metric because of some single issue like refugees where it gets little support, but in other issues it gets much more support. Thanks to David Rhys Bernard for this point. ↩︎

Appleby (2003, and in Sandilands and Hocking (2012)) argues the most persuasive explanation for why concern for animal welfare varies across Europe is that concern has developed largely in people who were less involved with animals than were others. The United Kingdom and the Netherlands, for example, are more industrialized than many other countries, and pressure for animal protection has come mostly from city dwellers rather than those involved in farming. Looking at which countries had then ratified the Council of Europe’s 1976 Convention on the Protection of Animals kept for Farming Purposes, most of the eleven that ratified first were from the north and had an average of only 6% of the population involved in agriculture. Countries that ratified later had a population average of 21% involved in agriculture. Most of these countries were southern. It is perhaps relevant to note then that of the large countries only Poland has over 6% of the workforce employed in agriculture today. ↩︎

Take the example of free trade. Some countries, for whatever reason, support international trade (e.g., Lithuania, Estonia, the Netherlands, and formerly the UK), while others (e.g., France, Italy) have a more protectionist tendency. ↩︎