In Defense of "Sweatshops"

By Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-18T17:58 (+57)

This is a linkpost to https://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2008/Powellsweatshops.html

This is a crosspost for In Defense of "Sweatshops" by Benjamin Powell, which was originally published on Econlib on 2 June 2008. For the full up to date treatment, see Benjamin's book Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy (Cambridge Studies in Economics, Choice, and Society), whose 2nd editions was published in January 2025.

“Because sweatshops are better than the available alternatives, any reforms aimed at improving the lives of workers in sweatshops must not jeopardize the jobs that they already have.”

I do not want to work in a third world “sweatshop.” If you are reading this on a computer, chances are you don’t either. Sweatshops have deplorable working conditions and extremely low pay—compared to the alternative employment available to me and probably you. That is why we choose not to work in sweatshops. All too often the fact that we have better alternatives leads first world activists to conclude that there must be better alternatives for third world workers too.

Economists across the political spectrum have pointed out that for many sweatshop workers the alternatives are much, much worse.[1] In one famous 1993 case U.S. senator Tom Harkin proposed banning imports from countries that employed children in sweatshops. In response a factory in Bangladesh laid off 50,000 children. What was their next best alternative? According to the British charity Oxfam a large number of them became prostitutes.[2]

The national media spotlight focused on sweatshops in 1996 after Charles Kernaghan, of the National Labor Committee, accused Kathy Lee Gifford of exploiting children in Honduran sweatshops. He flew a 15 year old worker, Wendy Diaz, to the United States to meet Kathy Lee. Kathy Lee exploded into tears and apologized on the air, promising to pay higher wages.

Should Kathy Lee have cried? Her Honduran workers earned 31 cents per hour. At 10 hours per day, which is not uncommon in a sweatshop, a worker would earn $3.10. Yet nearly a quarter of Hondurans earn less than $1 per day and nearly half earn less than $2 per day.

Wendy Diaz’s message should have been, “Don’t cry for me, Kathy Lee. Cry for the Hondurans not fortunate enough to work for you.” Instead the U.S. media compared $3.10 per day to U.S. alternatives, not Honduran alternatives. But U.S. alternatives are irrelevant. No one is offering these workers green cards.

What are the Alternatives to Sweatshops?

Economists have often pointed to anecdotal evidence that alternatives to sweatshops are much worse. But until David Skarbek and I published a study in the 2006 Journal of Labor Research, nobody had systematically quantified the alternatives.[3] We searched U.S. popular news sources for claims of sweatshop exploitation in the third world and found 43 specific accusations of exploitation in 11 countries in Latin America and Asia. We found that sweatshop workers typically earn much more than the average in these countries. Here are the facts:

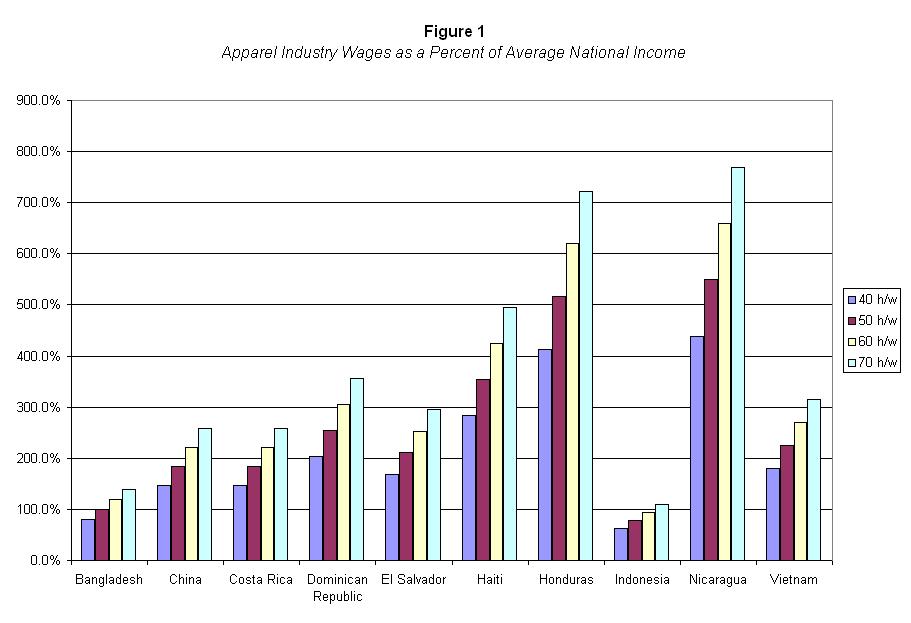

We obtained apparel industry hourly wage data for 10 of the countries accused of using sweatshop labor. We compared the apparel industry wages to average living standards in the country where the factories were located. Figure 1 summarizes our findings.[4]

Figure 1. Apparel Industry Wages as a Percent of Average National Income

ZOOM

Working in the apparel industry in any one of these countries results in earning more than the average income in that country. In half of the countries it results in earning more than three times the national average.[5]

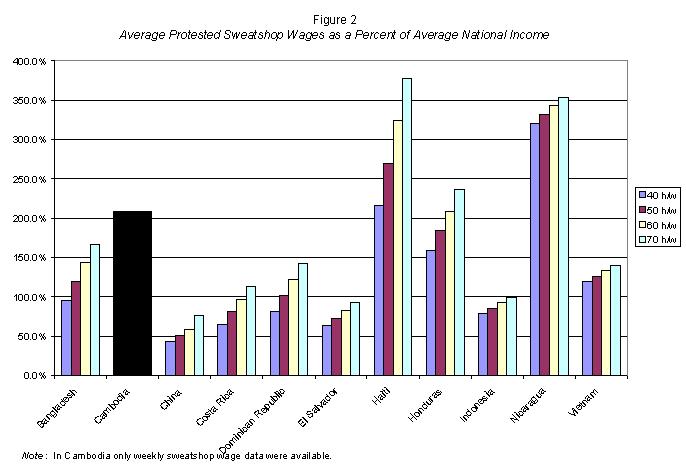

Next we investigated the specific sweatshop wages cited in U.S. news sources. We averaged the sweatshop wages reported in each of the 11 countries and again compared them to average living standards. Figure 2 summarizes our findings.

Figure 2. Average Protested Sweatshop Wages as a Percent of Average National Income

ZOOM

From “In Praise of Cheap Labor,” by Paul Krugman. Slate Magazine, March 1997:

A country like Indonesia is still so poor that progress can be measured in terms of how much the average person gets to eat; since 1970, per capita intake has risen from less than 2,100 to more than 2,800 calories a day. A shocking one-third of young children are still malnourished—but in 1975, the fraction was more than half. Similar improvements can be seen throughout the Pacific Rim, and even in places like Bangladesh. These improvements have not taken place because well-meaning people in the West have done anything to help—foreign aid, never large, has lately shrunk to virtually nothing. Nor is it the result of the benign policies of national governments, which are as callous and corrupt as ever. It is the indirect and unintended result of the actions of soulless multinationals and rapacious local entrepreneurs, whose only concern was to take advantage of the profit opportunities offered by cheap labor.

Even in specific cases where a company was allegedly exploiting sweatshop labor we found the jobs were usually better than average. In 9 of the 11 countries we surveyed, the average reported sweatshop wage, based on a 70-hour work week, equaled or exceeded average incomes. In Cambodia, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Honduras, the average wage paid by a firm accused of being a sweatshop is more than double the average income in that country. The Kathy Lee Gifford factory in Honduras was not an outlier—it was the norm.

Because sweatshops are better than the available alternatives, any reforms aimed at improving the lives of workers in sweatshops must not jeopardize the jobs that they already have. To analyze a reform we must understand what determines worker compensation.

What Determines Wages and Compensation?

If a Nicaraguan sweatshop worker creates $2.50 per hour worth of revenue (net of non-labor costs) for a firm then $2.50 per hour is the absolute most a firm would be willing to pay the worker. If the firm paid him $2.51 per hour, the firm would lose one cent per hour he worked. A profit maximizing firm, therefore, would lay the worker off.

From Nicholas D. Kristof, The New York Times, 14 January 2004:

And so I think what Americans don’t perhaps understand is that in a country like Cambodia, the exploitation of workers in sweatshops is a real problem, but the primary problem in places like this is not that there are too many workers being exploited in sweatshops, it’s that there are not enough. And a country like Cambodia would be infinitely better off if it had more factories using the cheap labor here and giving people a lift out of the unbelievably harsh conditions in the villages and even in the urban slums.

Of course a firm would want to pay this worker less than $2.50 per hour in order to earn greater profits. Ideally the firm would like to pay the worker nothing and capture the entire $2.50 of value he creates per hour as profit. Why doesn’t a firm do that? The reason is that a firm must persuade the worker to accept the job. To do that, the firm must offer him more than his next best available alternative.[6]

The amount a worker is paid is less than or equal to the amount he contributes to a firm’s net revenue and more than or equal to the value of the worker’s next best alternative. In any particular situation the actual compensation falls somewhere between those two bounds.

Wages are low in the third world because worker productivity is low (upper bound) and workers’ alternatives are lousy (lower bound). To get sustained improvements in overall compensation, policies must raise worker productivity and/or increase alternatives available to workers. Policies that try to raise compensation but fail to move these two bounds risk raising compensation above a worker’s upper bound resulting in his losing his job and moving to a less-desirable alternative.

What about non-monetary compensation? Sweatshops often have long hours, few bathroom breaks, and poor health and safety conditions. How are these determined?

Compensation can be paid in wages or in benefits, which may include health, safety, comfort, longer breaks, and fewer working hours. In some cases, improved health or safety can increase worker productivity and firm profits. In these cases firms will provide these benefits out of their own self interest. However, often these benefits do not directly increase profits and so the firm regards such benefits to workers as costs to itself, in which case these costs are like wages.

A profit-maximizing firm is indifferent between compensating workers with wages or compensating them with health, safety, and leisure benefits of the same value when doing so does not affect overall productivity. What the firm really cares about is the overall cost of the total compensation package.

Workers, on the other hand, do care about the mix of compensation they receive. Few of us would be willing to work for no money wage and instead take our entire pay in benefits. We want some of each. Furthermore, when our overall compensation goes up, we tend to desire more non-monetary benefits.

For most people, comfort and safety are what economists call “normal goods,” that is, goods that we demand more of as our income rises. Factory workers in third world countries are no different. Unfortunately, many of them have low productivity, and so their overall compensation level is low. Therefore, they want most of their compensation in wages and little in health or safety improvements.

Evaluating Anti-Sweatshop Proposals

For more on incentives facing lobbyists, listen to the EconTalk podcast Bruce Yandle on Bootleggers and Baptists.

The anti-sweatshop movement consists of unions, student groups, politicians, celebrities, and religious groups.[7] Each group has its own favored “cures” for sweatshop conditions. These groups claim that their proposals would help third world workers.

Some of these proposals would prohibit people in the United States from importing any goods made in sweatshops. What determines whether the good is made in a sweatshop is whether it is made in any way that violates labor standards. Such standards typically include minimum ages for employment, minimum wages, standards of occupational safety and health, and hours of work.[8]

Such standards do nothing to make workers more productive. The upper bound of their compensation is unchanged. Such mandates risk raising compensation above laborers’ productivity and throwing them into worse alternatives by eliminating or reducing the U.S. demand for their products. Employers will meet health and safety mandates by either laying off workers or by improving health and safety while lowering wages against workers’ wishes. In either case, the standards would make workers worse off.

The aforementioned Charles Kernaghan testified before Congress on one of these pieces of legislation, claiming:

Once passed, this legislation will reward decent U.S. companies which are striving to adhere to the law. Worker rights standards in China, Bangladesh and other countries across the world will be raised, improving conditions for tens of millions of working people. Your legislation will for the first time also create a level playing field for American workers to compete fairly in the global economy.[9]

From David R. Henderson, “The Case for Sweatshops.” Weekly Standard, 7 February 2000:

The next time you feel guilty for buying clothes made in a third-world sweatshop, remember this: you’re helping the workers who made that clothing. The people who should feel guilty are those who argue against, or use legislation to prevent us, giving a boost up the economic ladder to members of the human race unlucky enough to have been born in a poor country. Someone who intentionally gets you fired is not your friend.

Contrary to his assertion, anti-sweatshop laws would make third world workers worse off by lowering the demand for their labor. As his testimony alludes to though, such laws would make some American workers better off because they would no longer have to compete with third world labor: U.S. consumers would be, to some extent, a captive market. Although Kernaghan and some other opponents of sweatshops claim that they are attempting to help third world workers, their true motives are revealed by the language of one of these pieces of legislation: “Businesses have a right to be free from competition with companies that use sweatshop labor.” A more-honest statement would be, “U.S. workers have a right not to face competition from poor third world workers and by outlawing competition from the third world we can enhance union wages at the expense of poorer people who work in sweatshops.”

Kernaghan and other first world union members pretend to take up the cause of poor workers but the policies they advocate would actually make those very workers worse off. As economist David Henderson said, “[s]omeone who intentionally gets you fired is not your friend.”[10] Charles Kernaghan is no friend to third world workers.

Conclusion

Not only are sweatshops better than current worker alternatives, but they are also part of the process of development that ultimately raises living standards. That process took about 150 years in Britain and the United States but closer to 30 years in the Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

When companies open sweatshops they bring technology and physical capital with them. Better technology and more capital raise worker productivity. Over time this raises their wages. As more sweatshops open, more alternatives are available to workers raising the amount a firm must bid to hire them.

The good news for sweatshop workers today is that the world has better technology and more capital than ever before. Development in these countries can happen even faster than it did in the East Asian tigers. If activists in the United States do not undermine the process of development by eliminating these countries’ ability to attract sweatshops, then third world countries that adopt market friendly institutions will grow rapidly and sweatshop pay and working conditions will improve even faster than they did in the United States or East Asia. Meanwhile, what the third world so badly needs is more “sweatshop jobs,” not fewer.

- ^

Walter Williams, “Sweatshop Exploitation.” January 27, 2004. Paul Krugman, “In Praise of Cheap Labor, Bad Jobs at Bad Wages are Better Than No Jobs at All.” Slate, March 20, 1997.

- ^

Paul Krugman, New York Times. April 22, 2001.

- ^

Benjamin Powell and David Skarbek, “Sweatshop Wages and Third World Living Standards: Are the Jobs Worth the Sweat?” Journal of Labor Research. Vol. 27, No. 2. Spring 2006.

- ^

All figures are reproduced from our Journal of Labor Research article. See the original article for notes on data sources and quantification methods.

- ^

Data on actual hours worked were not available. Therefore, we provided earnings estimates based on various numbers of hours worked. Since one characteristic of sweatshops is long working hours, we believe the estimates based on 70 hours per week are the most accurate.

- ^

I am excluding from my analysis any situation where a firm or government uses the threat of violence to coerce the worker into accepting the job. In those situations, the job is not better than the next best alternative because otherwise a firm wouldn’t need to use force to get the worker to take the job.

- ^

It is a classic mix of “bootleggers and Baptists.” Bootleggers in the case of sweatshops are the U.S. unions who stand to gain when their lower priced substitute, 3rd world workers, is eliminated from the market. The “Baptists” are the true but misguided believers.

- ^

These minimums are determined by laws and regulations of the country of origin. For a discussion of why these laws should not be followed see Benjamin Powell, “In Reply to Sweatshop Sophistries.” Human Rights Quarterly. Vol. 28. No.4. Nov. 2006.

- ^

Testimonies at the Senate Subcommittee on Interstate Commerce, Trade and Tourism Hearing. Statement of Charles Kernaghan. February 14, 2007.

- ^

David Henderson, “The Case for Sweatshops.” Weekly Standard, 7 February 2000.

Tax Geek @ 2025-06-21T16:56 (+54)

Chris Blattman actually carried out some randomised controlled experiments with sweatshops in Ethiopia and published a paper in 2016 on the results. (The paper refers to these as "industrial jobs" but Blattman elsewhere has described them as "sweatshops".) They found that, contrary to traditional economic thinking, workers who got jobs in sweatshops were not necessarily better off than those who did not.

Most who got sweatshop jobs quit within just a few months, leaving the sector entirely. Those who stayed experience higher rates of serious health problems and disability compared to the control group. Income effects after a year did seem to be slightly higher for those in sweatshops compared to the control group, but not statistically significant.

The paper concludes:

Overall, the results suggest that that industrial firms in Ethiopia paid no better than worker’s informal alternatives, so that most workers were at best indifferent between these forms of work. This suggests a formal and informal labor market that was more fluid and competitive than expected, at least for the young, unskilled, and capital-poor.

Usual caveats apply about this being a limited study in Ethiopia, and more studies would be needed to see if the results generalise. But it is nevertheless an important study that challenges the traditional economic narrative of "sweatshop jobs are better than no jobs".

Ian Turner @ 2025-06-24T15:41 (+14)

It seems like even if workers are indifferent between the sweatshop jobs and the informal jobs, it could still be the case that the introduction of sweatshop jobs into the labor marketplace results in improvements for workers' conditions. For example, it could drive up the wages of informal labor.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-24T17:42 (+2)

Thanks for the comment, Ian! Strongly upvoted, and agreed.

Hugh P @ 2025-06-24T14:36 (+13)

most workers were at best indifferent between these forms of work

Wouldn't traditional economic thinking basically predict that the equilibrium for wages in industrial jobs be at the point where workers are indifferent to them? As in, there's no incentive for the wages in industrial jobs to be any higher than the level which is just high enough to compensate for the downsides (e.g. health risks) compared to the informal labour market? (I'm not an economist, and maybe this depends on what's considered "traditional".)

Tax Geek @ 2025-06-24T20:45 (+4)

Good point. The study undermines the traditional economic narrative that sweatshop jobs are clearly better than workers' alternatives - e.g. it would challenge this statement in the original post:

Economists across the political spectrum have pointed out that for many sweatshop workers the alternatives are much, much worse.

But it doesn't go so far as to show that sweatshops are clearly worse than workers' alternatives, either, which is what sweatshop opponents often claim. So it seems to be a middle-of-the-road finding that supports your idea that the Ethiopian labour market was actually more efficient than people had previously assumed. It's still notable because it challenges conventional wisdom on both sides of the debate.

The study had a third "entrepreneurship" condition that involved giving people $300 plus some business training. Unsurprisingly (imo), participants under that condition did better than both the sweatshop and control conditions. So while I don't think boycotting companies that use sweatshops is likely to be a very effective way of doing good, I don't think going out of your way to support sweatshops is likely to be worthwhile, either - there are likely to be better ways to promote economic development.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-25T10:44 (+3)

So while I don't think boycotting companies that use sweatshops is likely to be a very effective way of doing good, I don't think going out of your way to support sweatshops is likely to be worthwhile, either - there are likely to be better ways to promote economic development.

Agreed! I recommend donating to the High Impact Philanthropy Fund (HIPF) from the Centre for Exploratory Altruism Research (CEARCH) to increase human and animal welfare as cost-effectively as possible. Joel Tan, CEARCH’s founder and managing director, guessed on 28 May 2025 donating to HIPF was 9 to 15 times as cost-effective as donating to GiveWell's top charities, for which the mean cost of saving a life from 2021 to 2023 was 4.13 k$/life. Belows is some context about CEARCH's cost-effectiveness estimates.

[...] CEARCH estimated the cost-effectiveness accounting only for effects on humans, as a fraction of that of GiveWell’s top charities, of donating to Giving What We Can (GWWC) in 2025 to be 13, that of “advocacy for top sodium control policies to control hypertension” to be 31, that of advocating for “increasing the degree to which governments respond with effective food distribution measures, continued trade, and adaptations to the agricultural sector” in “global agricultural crises [such as nuclear and volcanic winters]” to be 33 (although I estimated this should be 12.4 % as high), and that of “advocacy for sugar-sweetened beverages [SSBs] taxes to control diabetes mellitus type 2” to be 55. Joel disclaimed he thinks the cost-effectiveness estimates from CEARCH’s deep reports, such as the ones I just mentioned, as well as (similarly elaborate) estimates from other impact-focussed evaluators, are 3 times as high as they should be. This largely explains why the mean between Joel’s lower and upper bound for the marginal cost-effectiveness of HIPF is only 21.8 % (= 12/55) of CEARCH’s highest cost-effectiveness estimate respecting advocacy for taxing SSBs.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-24T17:41 (+2)

Thanks for the comment, Hugh! Strongly upvoted, and agreed.

Rasool @ 2025-06-24T00:21 (+5)

Blattman discusses this on the Rationally Speaking podcast

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-21T21:26 (+3)

Thanks for sharing! Strongly upvoted. I like the study randomised people to receiving job offers instead of being placed into jobs. The opportunity to reject the offer makes it more like the real world.

Here is how the authors describe the effects on income.

On balance the factory job offer seems to have no significant effect on income by any of the three measures, and a family index of the three increases only 0.014 standard deviations.37 These income measures tend to be skewed and highly variable, however, and so our estimates are imprecise. Thus while the average effect is close to zero, the confidence interval on income includes moderate increases and decreases in income from the industrial job offer.

I guess the effect was slightly positive, but that the study was underpowered to detect it. The authors also note the workers think the increased health risks are worth it.

Naturally, workers were probably not perfectly informed about job risks and quality of these jobs, and there is some evidence that they underestimated the risk. Nonetheless, our data suggest that workers understood the health risks, at least in part, did not update their assessment of the risks as a result of spending more time in industry, and that they were willing to bear these risks to cope with temporary unemployment spells.

workers who got jobs in sweatshops were not necessarily better off than those who did

Nitpick. There is a "not" missing at the end.

Tax Geek @ 2025-06-22T12:56 (+3)

Thanks for the nitpick, I've fixed it in my post. Agree that the randomisation element is very useful.

Ian Turner @ 2025-06-21T02:28 (+13)

One thing that it seems to me often gets lost in this conversation is the assumption that the labor market is indeed a free market. Sweatshops seem fine to me if the labor is freely given; but when workers are locked in, chained to their machines, beat down when they try to organize, etc., it’s not clear to me that these free market conditions actually apply. The article mentions Cambodia, but Cambodia does not have a great reputation when it comes to corruption and governance. So, I think it’s worth asking, is the labor market free? If so then the rest of it seems sound to me.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-21T13:04 (+3)

Thanks for the comment, Ian. I think the conclusions hold as long as workers are calibrated about the distribution of their working conditions, including their pay, workload, treatment by managers, freedom to leave the job, go on strike, and coordinate with other workers, among others. A sufficiently low chance of being chained to machines is better than starving, and this may be the realistic alternative in some cases. So I think the existence of some of the working conditions you mentioned by itself is not enough to conclude it would be better for them not to exist. One would have to believe the workers are overestimating the quality of their working conditions (in expectation; it is always the case that some workers overestimate and others underestimate the quality of their working conditions).

Ian Turner @ 2025-06-21T13:12 (+7)

One would have to believe the workers are overestimating the quality of their working conditions

It seems to me very possible that workers might not have complete information about working conditions. It’s not like they necessarily get to go on a factory tour beforehand. In fact, from my understanding, broken promises are the norm rather than the exception with this sort of thing.

I also think your argument implicitly assumes that the work is freely taken up, and freely withdrawn, which isn’t necessarily the case either. More egregious things like the forced labor situation in the shrimp and cocoa industries exist, of course, but we have decent evidence there is forced labor in Cambodia also.

To be clear, I agree with the main argument of the piece, I just think we need to acknowledge that it rests on these other assumptions which are not necessarily guaranteed (and should anyway at least be made explicit).

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-21T19:43 (+3)

I agree workers have incomplete information, but it is unclear to me why they would systematically overestimate the value of jobs. If it is possible for foreign consumers to know that products from a given company or country were produced chaining workers to machines, I would expect the workers to also know about it given they have a much greater incentive to figure out their working conditions, as they directly reflect on their quality of life. My argument does assume workers freely take up jobs. The assumption that workers can freely leave their jobs is not strictly necessary, but it does help. In general, the greater the freedom of the workers to take up and leave jobs, the greater the transparency about the working conditions, and the greater the decision capacity of workers (adults have more than children), the stronger the case for assuming that taking the jobs was for the best, which I think is in agreement with what you are saying.

Eevee🔹 @ 2025-06-20T17:33 (+8)

This is a pretty grounded take. The only thing that bugs me is this passage, in the introduction:

The national media spotlight focused on sweatshops in 1996 after Charles Kernaghan, of the National Labor Committee, accused Kathy Lee Gifford of exploiting children in Honduran sweatshops. He flew a 15 year old worker, Wendy Diaz, to the United States to meet Kathy Lee. Kathy Lee exploded into tears and apologized on the air, promising to pay higher wages.

Should Kathy Lee have cried? Her Honduran workers earned 31 cents per hour. At 10 hours per day, which is not uncommon in a sweatshop, a worker would earn $3.10. Yet nearly a quarter of Hondurans earn less than $1 per day and nearly half earn less than $2 per day.

Wendy Diaz’s message should have been, “Don’t cry for me, Kathy Lee. Cry for the Hondurans not fortunate enough to work for you.” Instead the U.S. media compared $3.10 per day to U.S. alternatives, not Honduran alternatives. But U.S. alternatives are irrelevant. No one is offering these workers green cards.

One of the lessons I draw from this issue is that people, particularly those living in extreme poverty, may have preferences different from our own and different from what we'd expect given our assumptions about them. As the piece points out, factory workers in developing countries generally "want most of their compensation in wages and little in health or safety improvements.... Employers will meet health and safety mandates by either laying off workers or by improving health and safety while lowering wages against workers’ wishes." It's not our place to tell third-world workers that they should want improved working conditions more than they want moolah.

By the same token, I feel that it's arrogant for the author to tell poor people like Wendy Diaz what they should think or say, especially when he is using them to make a point. The piece doesn't tell us what Wendy told Kathy Lee Gifford, her putative "employer," but it's likely that she was testifying about her lived experiences working in the factory. Expectations color our perception of our life circumstances, so her outlook could have been subsequently shaped by her being flown north to the United States and getting a glimpse of what was possible outside her home country of Honduras. I can only speculate, so I'm being cautious not to project my beliefs onto Wendy as if she "should think X" or "did in fact feel Y." My point is that activists have a duty to respect the autonomy of their subjects—nothing about us without us.

Radical Empath Ismam @ 2025-06-22T13:59 (+5)

I actually think Kernaghan is making a good point and you've failed to appreciate his logic in full. Third world country businesses should not be able compete by having lower safety standards. Kernaghan is right, that creates a moral hazard, it pressures jurisdictions with high standards to lower them. It rewards bad behaviour here and there. We don't want that surely. No one wants that.

But third world country businesses should be able compete by having lower wages for their workers, operating in a low cost environment etc. That does accurately capture the relative economic advantage.

Jason @ 2025-06-23T03:32 (+8)

I'm somewhere in the middle. I would probably enforce certain minimum safety standards, but they wouldn't be full-strength developed country standards.

I can't see a compelling reason to impose the specific safety standards of (e.g.) the United States on factories in developing countries. Regulators consider the value of a statistical life in deciding whether to impose a specific requirement -- and at least one federal agency has that value pegged at over $13MM. The underlying methodology reflects the economic situation in the United States -- e.g., by asking people how much they would be willing to pay to reduce their risk of death (or demand in order to increase their risk of death), by looking at how much higher pay is in high-risk occupations like mining, by looking at lost earnings, and so on. There is no reason to believe those views are universally correct or wise in other contexts.

Employers in societies that do not agree with American sensibilities are not engaging in "bad behaviour" merely because they follow local norms rather than American ones. At least for countries with reasonably functioning democratic systems (or which we otherwise think are doing a respectable job governing in the interests of their citizens), it's not clear to me why we shouldn't usually defer to the level of safety that the society has determined to be generally appropriate. (By generally appropriate, I mean across the society as a whole -- I would not defer to regulations for industries that were more permissive than what was required in other regulatory domains).

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-23T09:54 (+2)

Thanks, Jason! I agree.

There is no reason to believe those views are universally correct or wise in other contexts.

Not only this, but there is also reason to believe people in lower income countries will be less willing to pay for safety because they have less money. Someone spending 100 $/d can afford 2 $/d to decrease their risk of death by e.g. 1 %. However, someone spending 2 $/d (close to the maximum income of people living in extreme poverty of 2.15 $/d) cannot afford 2 $/d because this would decrease their available spending to 0, which could lead to death from starvation without the support of others.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-22T17:46 (+2)

Thanks for the comment! Could you clarify why you think paying less is fine, but having lower safety standards is not? Increasing safety standards increases the cost of hiring workers, and therefore increases unemployment. Assuming a prospective worker is aware of the risks of the job, and still thinks the job is worth it, would you oppose the worker taking the job?

Jason @ 2025-06-23T03:56 (+4)

One needs to consider the harmful effects on other workers -- allowing goods to come into your market that were produced with abysmal safety standards puts pressure on other employers and their regulators to cut corners on safety. Pro-sweatshop logic is stronger at establishing that the sweatshop is not worse than the alternatives for the workers than at establishing its superiority to those alternatives. So the harms to non-sweatshop workers could outweigh any possible minor gains to the sweatshop workers.

I suspect most people are more sympathetic to developed-country workers who object to being undercut by unsafe labor than by inexpensive labor. There's an understanding that there are certain things you shouldn't be expected to do to keep your job -- agreeing to work in unsafe conditions, sleeping with the boss, voting a specific way -- and that society is going to enforce those boundaries. The right to safe working conditions may not mean very much in practice if you can get run out of business by factories outcompeting your employer because they use unsafe labor.

Radical Empath Ismam @ 2025-06-23T08:51 (+3)

That's the way our economic system works. Competing on the price of labour is fine and desirable - that helps sends signals to the global economy on how to order itself for optimal output.

But competing on safety is like a negative externality, like companies emitting pollution.

Safety is not an onerous cost either. As a cost, it would be in line with doing business in the jurisdiction. If the cost of labour is low in a poor country, so too is the lower cost of implementing safety.

Is there a specific country or example you would like to see safety standards held back on the grounds of higher employment? I've never heard of onerous safety standards being a cited as a reason for suppressed economic development. The Rana plaza fire safety reforms were widely lauded.

The Indian state of Kerala is widely recognised as having high living standards relative to the rest of India due to the strong presence of militant unions and labour standards.

Maybe there's a theoretic economic argument but it seems very edge-casey in the real world.

Jason @ 2025-06-23T22:20 (+6)

<<If the cost of labour is low in a poor country, so too is the lower cost of implementing safety.>>

That makes sense for some safety measures, but not all. If the cost is borne in terms of lost worker productivity, then it makes sense -- a safety measure resulting in a 5 percent productivity loss costs 1/10 as much where the cost of labor is 1/10 as expensive. But there are other kinds of safety costs as well -- imagine a requirement that a factory have one automated external defibrillator (AED) on site for every X workers. That isn't going to be meaningfully cheaper for the factory in the developing country.

NickLaing @ 2025-06-24T07:39 (+6)

Completely agree with Jason - its just not realistic.

Even simple things like metal Scaffolding and complicated harness/pully systems to protect from falls aren't meaningfully cheaper here (sometimes might even be more expensive), so people often use bamboo scaffolding and ropes to secure people instead.

There should be some kind of proportionality. Here in Uganda way more people die on the roads, and of curable diseases. For construction and industry to make sense withing the economy, its always going to be at least a bit more dangerous.

But yes, all the low hanging safety fruit which doesn't cost as much should be carefully implemented for sure.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-23T11:33 (+4)

But competing on safety is like a negative externality, like companies emitting pollution.

I do not think decreasing safety standards is like increasing pollution. Pollution decreases the quality of public goods like air and water bodies, which are often underprotected because the benefits are distributed across many people. In contrast, safety standards affect the health of workers, which is a private good, and therefore workers have a strong incentive to consider whether they are worth it.

Is there a specific country or example you would like to see safety standards held back on the grounds of higher employment? I've never heard of onerous safety standards being a cited as a reason for suppressed economic development. The Rana plaza fire safety reforms were widely lauded.

To clarify, I am not arguing that safety standards should be more or less strict. I just think they should be overwhelmingly determined by companies and workers instead of imposed by governments.

Empirical evidence about the effects of safety standards on employment is mixed, but this not surprising. There are lots of confounders, and it is difficult to rely on randomisation to isolate the effects of safety standards. However, "cost of labour" = "worker-hours"*("wage per worker-hour" + "other costs per worker-hour"), and imposing safety standards tends to increase "other costs per worker-hour", so companies will tend to decrease "worker-hours" and "wage per worker-hour" to compensate, thus decreasing employment and wages.

The Indian state of Kerala is widely recognised as having high living standards relative to the rest of India due to the strong presence of militant unions and labour standards.

I think the causality goes the other way around. A higher income per capita means people are willing to pay more to protect their health, and therefore push for stricter safety standards.

Radical Empath Ismam @ 2025-06-28T02:52 (+3)

You have a point that safety isn't a negative externality in the way pollution is. I will concede that. Never really thought of it like that.

To clarify, I am not arguing that safety standards should be more or less strict. I just think they should be overwhelmingly determined by companies and workers instead of imposed by governments.

Don't you think unions have an important role to play in this? Because as a worker, especially in a poor country, there's a lot of asymmetry. It's difficult and often impossible to assess the risk of a workplace before you've started. You lack the expertise to understand the breadth of all the safety issues, and don't have the information readily available to accurately compare safety across different firms.

And if governments can step in, productively with union & employer stakeholders, set sensible rules on safety (minimum safety standards, workplace assessment ratings), that makes it much easier for workers to assess safety of different firms, make better judgements, bargain for higher pay at more dangerous firms, allocate their labour more economical efficiently. Helps employers compete too.

Maybe you are arguing against the rules being too inflexible? Maybe you are just against first world unions don't always have the interests of third world workers in mind but maybe third world unions are ok?

"The Indian state of Kerala is widely recognised as having high living standards relative to the rest of India due to the strong presence of militant unions and labour standards."

I think the causality goes the other way around. A higher income per capita means people are willing to pay more to protect their health, and therefore push for stricter safety standards.

I wouldn't be so quick to dismiss the Kerala case study. Kerala actually has a lower per capita income. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerala_model

I think it's a good case study to challenge this line of argument. I'd say that example is a clear case where the causality is opposite to how you described. A lot of the social democratic countries show that trend. The Nordic countries famously were amongst the poorest parts of Europe when they adopted the Nordic model pushed by militant labour movements in those countries.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-28T10:23 (+2)

Thanks for the follow up.

I suspect prospective workers could get an idea of the safety risks by trying to talk with people who worked or work there. They could wait for them nearby the workplace. In some cases, they could also just work there to understand the conditions, and then quit if they do not like them.

I agree greater transparency about the working conditions is good, but I worry governments or unions pushing for rules on this may impose more costs than benefits.

I am not informed about Kerala's case study. I guess there are many cases that fit my narrative, and others that do not. However, in general, I am very confident that having a higher income increases the willingness to pay for health. The value of a statistical life tends to increase with income.

Mata'i Souchon @ 2025-06-20T09:07 (+5)

Thanks for sharing!

Do you know to what extent the arguments presented are still relevant 17 years later (particularly when it comes to observations made about the state of the labor market in certain developing countries in the early 2000s)?

Are you aware of any good critiques that have been made in response?

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-20T10:24 (+4)

Hi Mata,

The 2nd edition of Benjamin's book I linked at the start of the post was published in January 2025. I have now added this information to the start of the post.

I have not put much effort into finding critiques. I already had the prior that people working in sweatshops is good relative to the counterfactual. Otherwise, I would not have expected them to freely take the job. As a rule of thumb, I defer to people about what is best for them. This is not because I think people make optimal career choices. It is because I am sceptical of my ability to do better with very little knowledge about their situation (for example, just their country).

Tax Geek @ 2025-06-21T17:02 (+3)

The 2nd edition of Benjamin's book may have been published in 2025, but I'm not sure how much it updated from the 1st edition, which was published in 2014 - i.e. before the results of Blattman's 2016 paper that I mentioned in my other comment.

I have not read Benjamin's book but based on the Amazon description, it sounds like the 2025 edition contains fairly minimal updates.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-21T19:52 (+2)

Thanks for the good point! The 1st edition has 198 pages, and the 2nd has 236, so only 19.2 % (= 236/198 - 1) more pages.

Ian Turner @ 2025-06-21T02:26 (+4)

I thought this was kind of conventionally known (and covered by Milton Friedman in the 1980 PBS miniseries “freedom to choose”), if ignored by popular opinion. Is the new information here that we now have additional supporting quantitative evidence?

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-21T12:50 (+2)

Hi Ian,

I did not crosspost this due to new supporting quantitative evidence, but I think this is presented in the 2nd edition of Benjamin's book Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy (Cambridge Studies in Economics, Choice, and Society), which was published in January 2025.

artilugio @ 2025-06-20T16:34 (+4)

Are there any promising political or technical initiatives that exist or that you would like to see to increase the volume of exports and employment in low-income countries? What are some important barriers in the present? Tariffs? Inadequate infrastructure in very poor countries?

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-20T21:09 (+4)

Hi artilugiu,

You may be interested in Karthik Tadepalli's series on economic growth in low and middle income countries (LMICs). Part 3 addresses labour markets.

My recommendation for helping people in LMICs is donating to the High Impact Philanthropy Fund (HIPF) from the Centre for Exploratory Altruism Research (CEARCH). I estimate it is 12 times as cost-effective as GiveWell's top charities from the mean between the lower and upper bound of 9 and 15 mentioned by Joel Tan, CEARCH’s founder and managing director, on 28 May 2025. CEARCH estimated the cost-effectiveness accounting only for effects on humans, as a fraction of that of GiveWell’s top charities, of donating to Giving What We Can (GWWC) in 2025 to be 13, that of “advocacy for top sodium control policies to control hypertension” to be 31, that of advocating for “increasing the degree to which governments respond with effective food distribution measures, continued trade, and adaptations to the agricultural sector” in “global agricultural crises [such as nuclear and volcanic winters]” to be 33 (although I estimated this should be 12.4 % as high), and that of “advocacy for sugar-sweetened beverages [SSBs] taxes to control diabetes mellitus type 2” to be 55.

artilugio @ 2025-06-25T22:12 (+3)

Thank you for this info. Am i understanding correctly that advocacy for taxes on sugary drinks is estimated to be 55x more effective than donation to givewell's recommended charities?

Mo Putera @ 2025-06-26T04:01 (+4)

Yeah, higher in fact (the model's cost-eff estimate seems to be out of date vs the report summary's as it's lower DALYs averted per $100k). Keep in mind that policy advocacy is extremely hits-based (lots of nothingburgers per win, but the wins can be so big for the right problem/intervention combos you can still come out way ahead) compared to say nets or antimalarial drugs, a bit like VCs vs index funds in risk/return profile, so instead of looking only at EV, which is a fragile sequence thinking approach, you take a cluster thinking approach (which is better for making good decisions) and also consider things like the underlying theory of change's evidence quality (high in this case), expert views (checks out), and downsides (marginal), all of which the author analyses extensively.

Joel Tan🔸 @ 2025-06-26T04:14 (+4)

CEAs are always very uncertain and fragile, and I generally wouldn't put too much stock on the precise multiple relative to GiveWell. For us, we only really care if it's >GW, and we use >=10x as a nominal threshold to account for the fact that GiveWell generally spends a lot more time and effort discounting, relative to ourselves or Foudners Pledge or other researchers.

Overally, health policy interventions are uniquely cost-effective simply because of (a) large scale of impact (policies affect people across the whole country, or at least region or city); (b) low cost per capita (due to economies of scale), and this tends to outweigh the risk of failure (typically, we're looking at 10% success rates, though better charities in promising countries are closer to 30-50% maybe). Still, it's enormously risky, and remember that the median outcome is zero impact

Mo Putera @ 2025-06-26T08:51 (+4)

Yeah agreed, that's why I mentioned the cluster thing as a point in favor of your report's analytical methodology, and brought up the VC vs index fund analogy, essentially to steer the focus away from pure EV-maxing

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-26T12:58 (+2)

Thanks for the discussion!

instead of looking only at EV, which is a fragile sequence thinking approach, you take a cluster thinking approach (which is better for making good decisions) and also consider things like the underlying theory of change's evidence quality (high in this case), expert views (checks out), and downsides (marginal), all of which the author analyses extensively.

I think overwhelmingly relying on explicit quantitative cost-effectiveness analyses is generally better. However, one should be mindful to account for considerations not covered, and that one can often cover more considerations by not modelling them formally.

People often point to GiveWell's posts on not taking expected value estimates literally, and sequence versus cluster thinking to moderate enthusiam about explicit quantitative cost-effectiveness analyses, but GiveWell overwhelmingly relies on these. Elie Hassenfeld, GiveWell's CEO, mentioned on the Clearer Thinking podcast that:

GiveWell cost- effectiveness estimates are not the only input into our decisions to fund malaria programs and deworming programs, there are some other factors, but they're certainly 80% plus of the case.

There is more context from GiveWell here. The key parts are below.

The numerical cost-effectiveness estimate in the spreadsheet is nearly always the most important factor in our recommendations, but not the only factor. That is, we don’t solely rely on our spreadsheet-based analysis of cost-effectiveness when making grants.

- We don't have an institutional position on exactly how much of the decision comes down to the spreadsheet analysis (though Elie's take of "80% plus" definitely seems reasonable!) and it varies by grant, but many of the factors we consider outside our models (e.g. qualitative factors about an organization) are in the service of making impact-oriented decisions. See this post for more discussion.

- For a small number of grants, the case for the grant relies heavily on factors other than expected impact of that grant per se. For example, we sometimes make exit grants in order to be a responsible funder and treat partner organizations considerately even if we think funding could be used more cost-effectively elsewhere.

Mo Putera @ 2025-06-26T16:15 (+4)

I've read those comments awhile back and I don't think they support your view for relying overwhelmingly on explicit quantitative cost-effectiveness analyses. In particular the key parts I got out of Isabel's comment weren't what you quoted but instead (emphasis mine not hers)

Cost-effectiveness is the primary driver of our grantmaking decisions. But, “overall estimated cost-effectiveness of a grant” isn't the same thing as “output of cost-effectiveness analysis spreadsheet.” (This blog post is old and not entirely reflective of our current approach, but it covers a similar topic.)

and

That is, we don’t solely rely on our spreadsheet-based analysis of cost-effectiveness when making grants.

which is in direct contradistinction to your style as I understand it, and aligned with what Holden wrote earlier in that link you quoted (emphasis his this time)

While some people feel that GiveWell puts too much emphasis on the measurable and quantifiable, there are others who go further than we do in quantification, and justify their giving (or other) decisions based on fully explicit expected-value formulas. The latter group tends to critique us – or at least disagree with us – based on our preference for strong evidence over high apparent “expected value,” and based on the heavy role of non-formalized intuition in our decisionmaking. This post is directed at the latter group.

We believe that people in this group are often making a fundamental mistake, one that we have long had intuitive objections to but have recently developed a more formal (though still fairly rough) critique of. The mistake (we believe) is estimating the “expected value” of a donation (or other action) based solely on a fully explicit, quantified formula, many of whose inputs are guesses or very rough estimates. We believe that any estimate along these lines needs to be adjusted using a “Bayesian prior”; that this adjustment can rarely be made (reasonably) using an explicit, formal calculation; and that most attempts to do the latter, even when they seem to be making very conservative downward adjustments to the expected value of an opportunity, are not making nearly large enough downward adjustments to be consistent with the proper Bayesian approach.

This view of ours illustrates why – while we seek to ground our recommendations in relevant facts, calculations and quantifications to the extent possible – every recommendation we make incorporates many different forms of evidence and involves a strong dose of intuition. And we generally prefer to give where we have strong evidence that donations can do a lot of good rather than where we have weak evidence that donations can do far more good – a preference that I believe is inconsistent with the approach of giving based on explicit expected-value formulas (at least those that (a) have significant room for error (b) do not incorporate Bayesian adjustments, which are very rare in these analyses and very difficult to do both formally and reasonably).

Note that I'm not saying CEAs don't matter, or that CEA-focused approaches are unreliable — I'm a big believer in the measurability of things people often claim can't be measured, I think in principle EV-maxing is almost always correct but in practice it can be perilous and on the margin people should instead be working a bit more on how different moral conceptions cash out in different recommendations more systematically e.g. with RP's work, if a CEA-based case can't be made for a grant I get very skeptical, I in fact also consider CEAs the main input into my thinking on these kinds of things, etc. I am simply wary of single-parameter optimisation taken to the limit in general (for anything, really, not just for donating), and I see your approach as being willing to go much further along that path than I do (and I'm already further along that path than almost anyone I meet IRL).

But I've seen enough back-and-forth between people in the cluster and sequence camps to have the sense that nobody really ends up changing their mind substantively and I doubt this will happen here either, sorry, so I will respectfully bow out of the conversation.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-26T16:32 (+2)

Thanks for the context, Mo!

Joel Tan🔸 @ 2025-06-26T13:49 (+4)

I think there's something to be said that if the qualitative stuff looks bad (e.g. experts are negative, studies are bunch of non-randomized stuff susceptible to endogeneity concerns), you always have the option of just implementing aggressive discounts to the CEA, and the fact that it looks too good means the CEA is done poorly, not that the CEA-focused approach is unreliable.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-06-26T14:37 (+2)

Makes sense. I also like explicit quantification because it is more transparent, making it easier to examine assumptions, identify main uncertainties, and therefore improve estimates in the future. With approaches associated with cluster thinking, I think it is often unclear which assumptions are driving the decisions, or whether the decisions being made actually follow from the assumptions.