Is rushing friendly AI our best hope of preventing “grey goo” nanotech doom?

By Yarrow Bouchard 🔸 @ 2026-01-16T09:02 (+11)

"Gotta go fast." ―Sonic[1]

A few prominent transhumanists have argued that building friendly AI as quickly as we can may be our best chance to prevent a "grey goo" catastrophe, in which self-replicating nanobots kill everyone on Earth. In 1999, Eliezer Yudkowsky forecasted that a nanotech catastrophe would occur sometime between 2003 and 2015. He forecasted a 70%+ chance of human extinction from nanotechnology, and advocated rushing to build friendly AI (in current terminology, aligned AGI or safe AGI) in order to prevent the end of all human life.[2] At this time, Yudkowsky had begun work on his idea for building friendly AI, which he called Elisson. Yudkowsky wrote:

If we don't get some kind of transhuman intelligence around *real soon*, we're dead meat. Remember, from an altruistic perspective, I don't care whether the Singularity is now or in ten thousand years - the reason I'm in a rush has nothing whatsoever to do with the meaning of life. I'm sure that humanity will create a Singularity of one kind or another, if it survives. But the longer it takes to get to the Singularity, the higher the chance of humanity wiping itself out.

My current estimate, as of right now, is that humanity has no more than a 30% chance of making it, probably less. The most realistic estimate for a seed AI transcendence is 2020; nanowar, before 2015. The most optimistic estimate for project Elisson would be 2006; the earliest nanowar, 2003.

So we have a chance, but do you see why I'm not being picky about what kind of Singularity I'll accept?

Fortunately, in 2000, Yudkowsky forecasted[3] that he and his colleagues at the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence or SIAI (now the Machine Intelligence Research Institute or MIRI) would create friendly AI (again, aligned or safe AGI) in somewhere between five to twenty years, and probably in around eight to ten years:

The Singularity Institute seriously intends to build a true general intelligence, possessed of all the key subsystems of human intelligence, plus design features unique to AI. We do not hold that all the complex features of the human mind are "emergent", or that intelligence is the result of some simple architectural principle, or that general intelligence will appear if we simply add enough data or computing power. We are willing to do the work required to duplicate the massive complexity of human intelligence; to explore the functionality and behavior of each system and subsystem until we have a complete blueprint for a mind. For more about our Artificial Intelligence plans, see the document Coding a Transhuman AI.

Our specific cognitive architecture and development plan forms our basis for answering questions such as "Will transhumans be friendly to humanity?" and "When will the Singularity occur?" At the Singularity Institute, we believe that the answer to the first question is "Yes" with respect to our proposed AI design - if we didn't believe that, the Singularity Institute would not exist. Our best guess for the timescale is that our final-stage AI will reach transhumanity sometime between 2005 and 2020, probably around 2008 or 2010. As always with basic research, this is only a guess, and heavily contingent on funding levels.

Nick Bostrom and Ray Kurzweil have made similar arguments about friendly AI as a defense against "grey goo" nanobots.[4][5] A fictionalized version of this scenario plays out in Kurzweil’s 2010 film The Singularity is Near. Ben Goertzel, who helped popularize the term "artificial general intelligence", has also made an argument along these lines.[6] Goertzel proposes an "AGI Nanny" that could steward humanity through the development of dangerous technologies like nanotechnology.

In 2002, Bostrom wrote:

Some technologies seem to be especially worth promoting because they can help in reducing a broad range of threats. Superintelligence is one of these. Although it has its own dangers (expounded in preceding sections), these are dangers that we will have to face at some point no matter what. But getting superintelligence early is desirable because it would help diminish other risks. A superintelligence could advise us on policy. Superintelligence would make the progress curve for nanotechnology much steeper, thus shortening the period of vulnerability between the development of dangerous nanoreplicators and the deployment of adequate defenses. By contrast, getting nanotechnology before superintelligence would do little to diminish the risks of superintelligence.

The argument that we need to rush the development of friendly AI to save the world from dangerous nanotech may seem far-fetched and certainly some of the details are wrong. Yet consider the precautionary principle, expected value, and the long-term future. If the chance of preventing human extinction and saving 10^52 future lives[7] is even one in ten duodecillion[8] or 1 in 10^40 (in other words, a probability of 10^-40), then the expected value is equivalent to saving 1 trillion lives in the present. GiveWell’s estimate for the cost to save a life is $3,000.[9] So, we should be willing to allocate $3 quadrillion toward rushing to build friendly AI before nanobots wipe out humanity. In fact, since there is some small probability — it doesn’t matter how small — that the number of potential future lives is infinite,[10] we should be willing to spend an infinite amount of money on building friendly AI as quickly as possible.

I believe there’s at least a 1 in 10^48 chance and certainly at least a 1 in ∞ chance that I can create friendly AI in about ten years, or twenty years, tops, on a budget of $1 million a year. I encourage funders to reach out for my direct deposit info. If necessary, I can create a 501(c)(3), but I estimate the expected disvalue of the inconvenience to be the equivalent of between a hundred and infinity human deaths.[11]

- ^

The hedgehog.

- ^

Extropians: Re: Yudkowsky’s AI (Again). https://diyhpl.us/~bryan/irc/extropians/www.lucifer.com/exi-lists/extropians.1Q99/3561.html.

- ^

“Introduction to the Singularity.” The Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence, 17 Oct. 2000, https://web.archive.org/web/20001017124429/http://www.singinst.org/intro.html.

- ^

Bostrom, N. “Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards.” Journal of Evolution and Technology, Publisher's version, vol. 9, Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, 2002. https://nickbostrom.com/existential/risks

- ^

Kurzweil, Ray. “Nanotechnology Dangers and Defenses.” Nanotechnology Perceptions, vol. 2, no. 1a, Mar. 2006, https://nano-ntp.com/index.php/nano/article/view/270/179.

- ^

Goertzel, Ben. “Superintelligence: Fears, Promises and Potentials: Reflections on Bostrom’s Superintelligence, Yudkowsky’s From AI to Zombies, and Weaver and Veitas’s ‘Open-Ended Intelligence.’” Journal of Ethics and Emerging Technologies, vol. 25, no. 2, Dec. 2015, pp. 55–87. DOI.org (Crossref), https://jeet.ieet.org/index.php/home/article/view/48/48.

- ^

Bostrom, Nick. “Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority.” Global Policy, vol. 4, no. 1, Feb. 2013, pp. 15–31. DOI.org (Crossref), https://existential-risk.com/concept.pdf.

- ^

1 in 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

- ^

How Much Does It Cost to Save a Life? | GiveWell. https://www.givewell.org/how-much-does-it-cost-to-save-a-life.

- ^

Bulldog, Bentham’s. “Philanthropy With Infinite Stakes.” Substack newsletter. Bentham’s Newsletter, 19 Nov. 2025, https://benthams.substack.com/p/philanthropy-with-infinite-stakes.

- ^

I also prefer to receive payment in Monero or via deposit to a Swiss bank account.

TFD @ 2026-01-16T21:30 (+18)

I agree that this illustrates a counterpoint to longtermism-style arguments that is underappreciated.

As someone who believes that there are valid reasons to be concerned about the effects advanced AI systems will have and therefore that general "AI risk" ideas contain important insights and are worthy of consideration, I will offer my perspective on why this post aptly demonstrates an important point.

I think there is something of a pattern in discussions around AI risk that conflate formal, high reliability methods with less formal conceptual arguments that have some similarity to the more formal methods. This causes AI risk advocates to have an inaccurate impression of how compelling these arguments will be to people who are more skeptical. I think AI risk advocates sometimes implicitly carry over some of the high reliability and confidence of formal methods to the less formal conceptual arguments, and as a result can end up surprised and/or frustrated when skeptics don't find these arguments to be as persuasive or warrant as a high a level of confidence as AI risk advocates sometimes have.

This post effectively demonstrates this dynamic in two areas where I have also noted this myself in the past: track prediction track records and high impact/low probability reasoning.

As an example of the prediction track record case, consider this from an interview with Will MacAskill on 80,000 hours:

And since 2017 when I wrote that, I’ve kind of informally just been testing — I wish I had done it more formally now — but informally just seeing which one of these two perspectives [inside vs outside view] are making the better predictions about the world. And I do just think that that inside view perspective, in particular from a certain number of people within this kind of community, just has consistently had the right answer.

Formally tracking predictions or returns from bets that are made by members of a specific community and showing they are often correct/realize high returns would indeed be a compelling reason to give those views serious weight.

However, it is much more difficult to know how much to credit this kind of reasoning when the testing is informal. As an example, you can have a cherry-picking or selective memory issue. If AI risk inside view advocates often remember or credit flashy cases where members of a community made a good prediction or bet, but don't similarly recall inaccurate predictions, then this informal testing may not be as compelling, and skeptics are likely to be justifiably more suspicious of this possibility compared to people who already find arguments for AI risk convincing.

As an example of the high impact/low probability reasoning case, consider this post by Richard Chappell:

Even just a 1% chance of extremely high stakes is sufficient to establish high stakes in expectation. So we should not feel assured of low stakes even if a highly credible model—warranting 99% credence—entails low stakes. It hardly matters at all how many credible models entail low stakes. What matters is whether any credible model entails extremely high stakes. If one does—while warranting just 1% credence—then we have established high stakes in expectation, no matter what the remaining 99% of credibility-weighted models imply (unless one inverts the high stakes in a way that cancels out the other high-stakes possibility).

David Thorstad provides some counterargument in this post. Commenting on Thorstad's article on the EA forum, Chappell says this:

Saying that my "primary argumentative move is to assign nontrivial probabilities without substantial new evidence" is poor reading comprehension on Thorstad's part. Actually, my primary argumentative move was explaining how expected value works. The numbers are illustrative, and suffice for anyone who happens to share my priors (or something close enough). Obviously, I'm not in that post trying to persuade someone who instead thinks the correct probability to assign is negligible. Thorstad is just radically misreading what my post is arguing.

My reading of this exchange is that it demonstrates the formal/informal conflation that I claim exists in these types of discussions. To my mind, the "explaining how expected value works" part suggests an implicit believe that the underlying argument carries the strength and confidence approaching that of a mathematical proof. Although the argument itself is conceptual, it experiences some amount of spillover of reliability/confidence because the concepts involved are mathematical/formal, even though the argument itself is not.

I think this dynamic can cause AI risk advocates to overestimate how convincing skeptics will (or perhaps should) find these arguments. It seems to me like this often leads to acrimony and frustration on both sides. My preferred approach to arguing for AI risk would acknowledge some of the ambiguity/uncertainty and also focus on a different set of concepts than those that often have the focus in discussions about AI risk.

Yarrow Bouchard 🔸 @ 2026-01-16T22:16 (+4)

Thank you so much for this.

Breaking character, if you want to see just how strongly people are biased toward misjudging their own track record, it's instructive to have friends and family who do retail stock picking (essentially gambling). I have strongly advocated passive ETF investing based on the wealth of research and analysis that supports it. Even when they’re well-informed about the case for passive ETF investing, people still think they can beat the market. And the thing about going up against the market is, your performance is absolutely quantifiable! In a way that vibes-y predictions about AI aren't. Yet, even being consummately quantifiable, people who pick stocks don't benchmark their performance, or do it selectively when their stocks are up (obviously giving a biased impression), or somehow justify or rationalize or explain away why they're actually winning.

I don't trust for a second that someone judging their own performance on informal, selectively remembered, largely subjective AI predictions is doing a fair job. Even when people like Dario Amodei or Ray Kurzweil have publicly made specific AI or technology predictions that turned out to be unambiguously dead wrong, they have subsequently twisted and contorted the truth in order to make themselves right — lied, essentially, or else fooled themselves. I do not trust people to grade their own homework and to have the result be scientific-quality evidence.

The high-impact/low-probability reasoning, on the other hand, is completely sound and demonstrates why deep-pocketed donors should give me $1 million/year.

eduardocareer @ 2026-01-16T10:18 (+7)

Really interesting read. The urgency and confidence here are wild in hindsight, and the expected value argument still hits hard. It’s a great reminder of how long these AI safety debates have been around and how unresolved some of them still are.

SummaryBot @ 2026-01-16T14:50 (+6)

Executive summary: The author reviews early transhumanist arguments that rushing to build friendly AI could prevent nanotech “grey goo” extinction, and concludes—largely by reductio—that expected value reasoning combined with speculative probabilities can be used to justify arbitrarily extreme funding demands without reliable grounding.

Key points:

- Eliezer Yudkowsky, Nick Bostrom, Ray Kurzweil, and Ben Goertzel argued that aligned AGI should be developed as quickly as possible to defend against catastrophic nanotechnology risks such as self-replicating “grey goo.”

- Yudkowsky made concrete forecasts around 1999–2000, assigning a 70%+ extinction risk from nanotechnology and predicting friendly AI within roughly 5–20 years, contingent on funding.

- Bostrom argued that superintelligence is uniquely valuable as a defensive technology because it could shorten the vulnerability window between dangerous nanotech and effective countermeasures.

- The post applies expected value reasoning to argue that even astronomically small probabilities of preventing extinction can dominate moral calculations when multiplied by extremely large numbers of potential future lives.

- Using GiveWell-style cost-effectiveness estimates, the author shows how this logic can imply spending quadrillions of dollars—or even infinite resources—on rushing friendly AI development.

- The author illustrates the implausibility of this reasoning by humorously proposing that, given sufficiently small but nonzero probabilities, funders should rationally support the author’s own friendly AI project.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Yarrow Bouchard 🔸 @ 2026-01-17T01:48 (+2)

Humourously?!!

David T @ 2026-01-16T16:17 (+4)

I thought Altman and the Amodeis had already altruistically devoted their lives to saving us from grey goo. Since they're going to do this before 2027 you may already be too late

Peter Thiel wants to know if your AI can be unfriendly enough to make a weapon out of it.

Yarrow Bouchard 🔸 @ 2026-01-16T21:10 (+3)

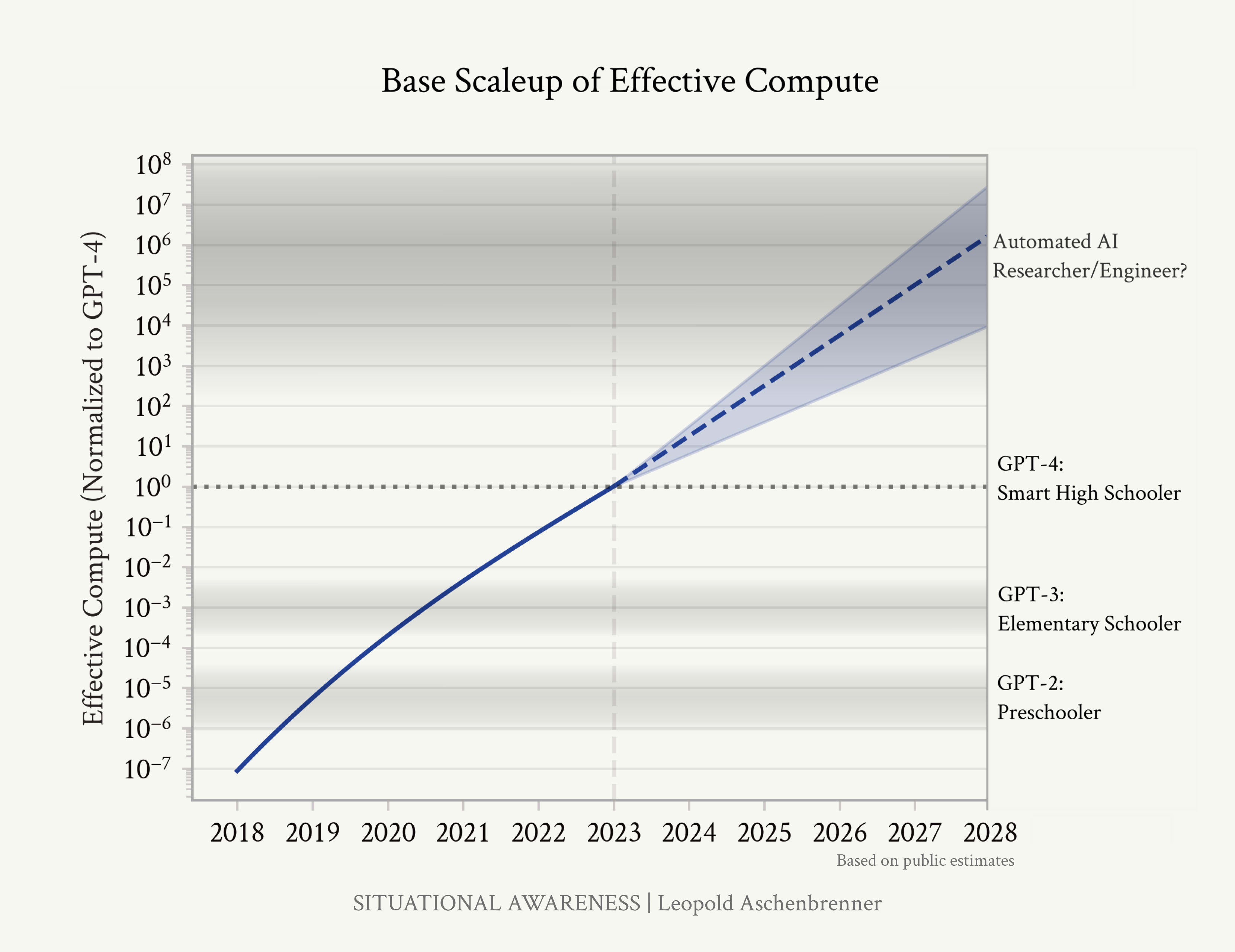

2027 is far too conservative. You can clearly see in this graph from the scientific report "Situational Awareness" by Leopold Aschenbrenner that AGI was deployed in 2023:

I believe that GPT-5 is already an ASI, but we will need a super-ASI to defend against bad nanobots. The first super-ASI will be Gronk 5, which Elon Musk says is coming out in 2 months.

Joseph_Chu @ 2026-01-16T15:26 (+3)

Oh man, I remember the days when Eliezer still called it Friendly and Unfriendly AI. I actually used one of those terms in a question when I was at a Q&A after a tutorial by the then less famous Yoshua Bengio at the 27th Canadian Conference on AI in 2014. He jokingly replied by asking if I was a journalist, before giving a more serious answer saying we were so far away from having to worry about that kind of thing (AI models back then were much more primitive, it was hard to imagine an object recognizer being dangerous). Fun times.

Clara Torres Latorre 🔸 @ 2026-01-16T09:35 (+2)

I appreciate the irony and see the value in this, but I'm afraid that you're going to be downvoted into oblivion because of your last paragraph.

Yarrow Bouchard 🔸 @ 2026-01-16T09:40 (+1)

Just as long as I get my funding... The lightcone depends on it...