Do countries comply with EU animal welfare laws?

By Neil_Dullaghan🔹 @ 2020-08-17T01:18 (+68)

Summary

- Compliance with animal welfare laws is not automatic and often requires enforcement actions.

- While the European Union (EU) is often held up as a high global benchmark for the stringency of their animal welfare laws, many EU countries appear to fall short when applying these laws on the ground.

- ~33 million to ~97 million hens (9%-27% of EU total) a year may have illegally remained in conventional battery cages for up to five years if additional enforcement action was not taken.

- ~1 million to ~2.5 million sows (8%-19% of EU total) a year may have illegally remained in individual stalls for up to seven years if additional enforcement action was not taken.

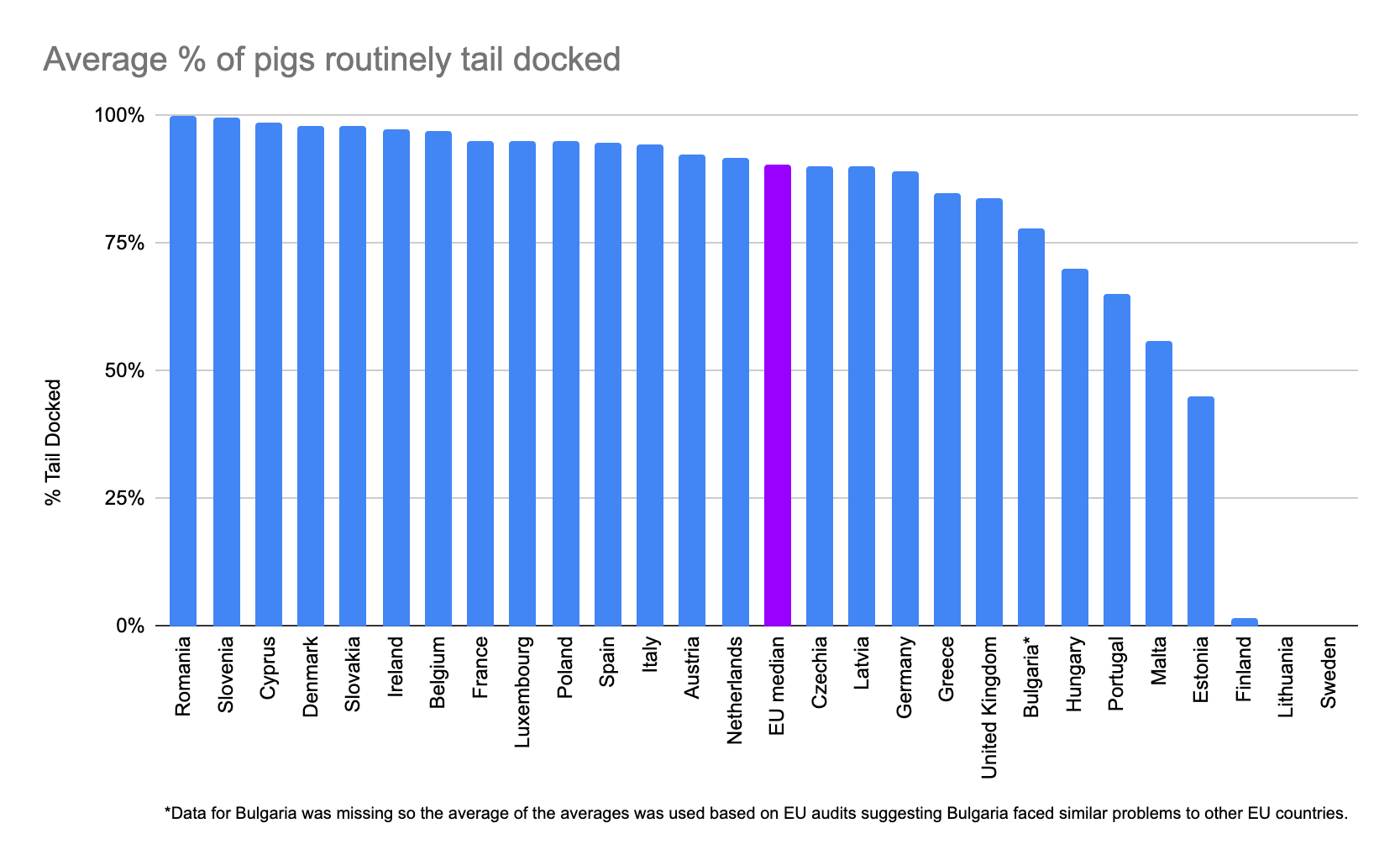

- ~52 million to ~116 million pigs (35%-86% of EU total) on average are being tail docked without the required alternative methods for reducing tail biting being implemented.

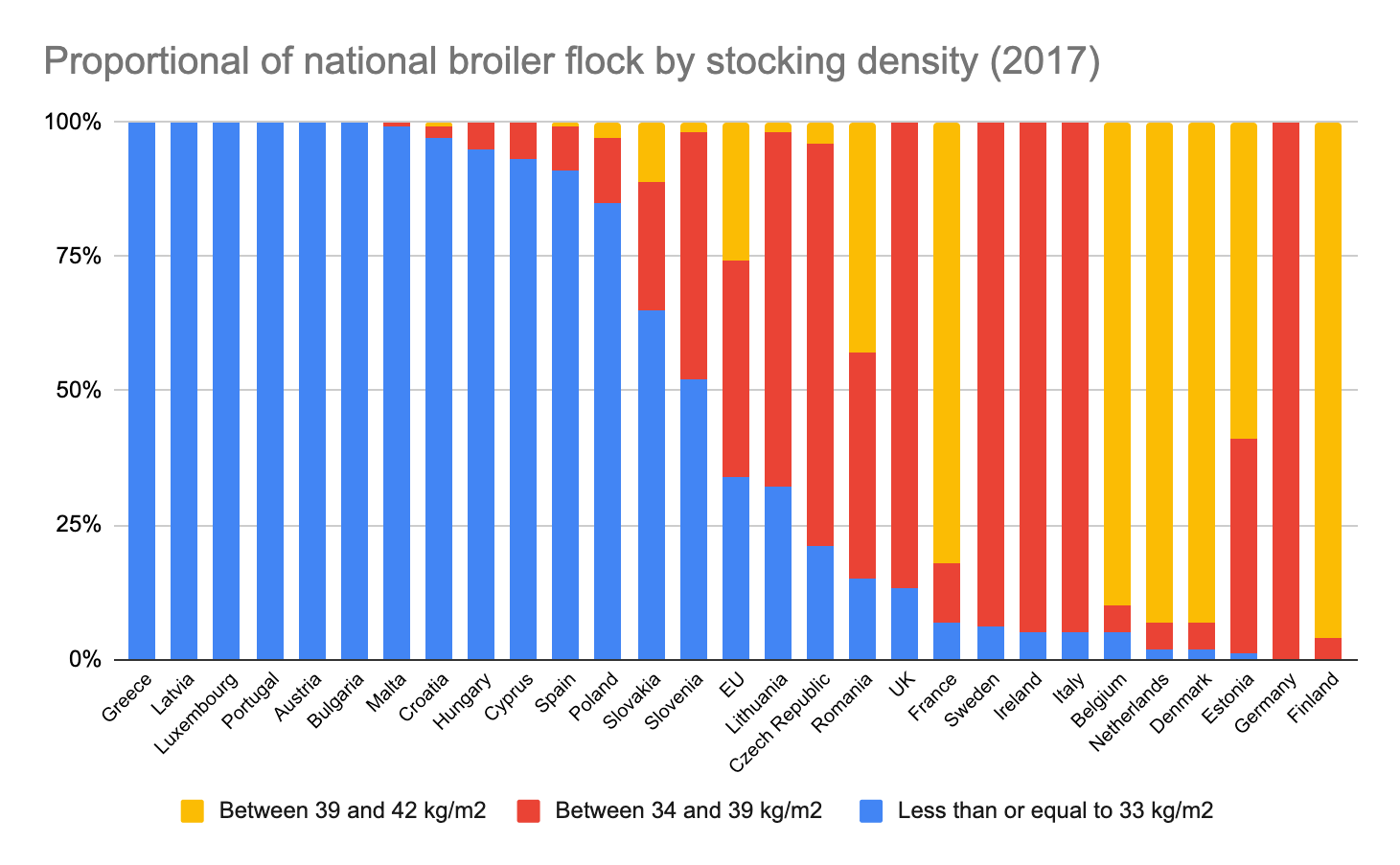

- ~1.5 billion to ~4.6 billion broiler chickens slaughtered each year (21%-66% of EU total) may be stocked at high densities without the required additional welfare conditions.

- Millions of Euros in EU rural development funds available for improving animal welfare goes unused or poorly used.

- National inspections and fines are an effective tool to reduce noncompliance, but only when the political will is there to apply them.

- Enacting national laws in countries with high public concern for animal welfare may be an effective first step to ensure later equivalent EU level laws are complied with in other EU countries.

- Litigation in administrative courts against lenient inspection authorities and noncompliance awareness campaigns led by animal welfare organizations may be useful tools for improving compliance.

Introduction

The European Union may be an arena where there are promising opportunities to improve farmed animal welfare through legislation due to historic legal precedents, high public concern for farmed animals, a professional animal protection movement, and new momentum for legislation (see our first post in this series outlining EU law as an arena for farmed animal welfare). Pushing for higher minimum farmed animal welfare standards in law has brought many victories in Europe, but laws are only as good as their implementation. As the animal welfare movement continues to push for higher legal standards for a wider range of farmed animals, one should also pay attention to whether these standards are being practiced in reality. In this report by Rethink Priorities, we focus on the European Union as an example of legislative protection of farmed animal welfare and detail the mechanisms by which compliance is sought. [1]

This is not intended to be the last word on noncompliance with animal welfare laws, but rather to shine a light on the issue and generate future research and work in this area. After outlining the general framework for compliance in the EU, we offer case studies of the major species-specific welfare directives (the conventional battery cage ban for egg-laying hens and partial restrictions on individual stalls for sows, narrow crates for calves, and restrictions on broiler stocking density and tail docking of pigs) as examples of this system succeeding and failing. It is hoped this will highlight what a robust system of compliance could look like, and what bottlenecks and opportunities can be seized on to improve animal lives. For those already familiar with how the EU compliance system works, or just want to read about how it has worked in practice, you may want to skip ahead to the case studies.

The cases below illustrate the farmed animal industry’s unwillingness to improve the lives of animals voluntarily, and even when required to do so by law. The bans on conventional battery cages and sow stalls were not widely acted upon until the EU, under pressure from already compliant countries and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), reaffirmed the deadlines would not be postponed and national authorities stepped up inspections in the face of potential trade bans and legal action. On the other hand, the partial ban on routine tail docking has been marred by perceived widespread noncompliance and a reluctance by the authorities to sanction producers, and requirements on broiler stocking density appear to not be monitored sufficiently for us to know if they are being met. The partial ban on narrow veal crates appears to have been the most successful due to the small number of countries affected.

This suggests that campaigns to pass farmed animal welfare laws may be less effective than assumed if they do not consider noncompliance. One may argue that so long as a law eventually leads to most producers providing higher animal welfare it is not cost-effective for animal welfare groups to act to ensure that all producers do so, nor that they do so by the arbitrary deadline set out in the legislation. However, as the cases below suggest, it appears that without additional pressure from animal groups, lobbyists, agricultural associations, and governments many noncompliant producers would have continued to operate for many years without curtailment, negatively affecting significant numbers of farmed animals. Furthermore, longterm noncompliance can also provide grounds and confidence for repealing the law. One should also keep in mind that we probably should not expend energies on enforcing laws with bad welfare outcomes or trying to increase compliance with laws that are inherently unenforceable due to vague wording and impractical measures. A question thus becomes are enforceable laws that would improve welfare actually complied with sufficiently enough for us not to worry about the noncompliers?

How bad is noncompliance with animal welfare laws in the EU?

What farmed animal welfare laws does the EU have?

It is important to remember that the EU is in large part a trading bloc designed to reduce internal barriers to goods and services and to protect members from competitors abroad by erecting high tariff barriers to third countries’ competing products. Any discussion of animal welfare laws should keep in mind that they are subject to this underlying motivation. In the absence of measures from the EU institutions to level the playing field among EU countries, one should probably expect a race-to-the-bottom in search of profit at the expense of animal welfare. Therefore, one should not be surprised that animal welfare is not prioritised or complied with, but rather that it has been given any legal standing or enforcement at all. In this report we focus on the species-specific laws that place partial restrictions on three systems most classically associated with industrial farming:[2] narrow crates for veal calves[3] (enforceable since 2007), conventional battery cages for egg-laying hens[4] (enforceable since 2012), and sow stalls (restrictive metal enclosures in which pregnant pigs are kept) for pigs[5] (enforceable since 2013), as well as setting stocking density standards for broiler chickens[6] (enforceable since 2010) and prohibiting routine tail docking of pigs (since 1994 and codified in the 2008 Pigs directive). The law providing very general protection of “all” farm animals[7] (since 1998) and the two major regulations concerning transport (since 1977 and updated in 2005) and slaughter (since 1974 and updated in 1993 and 2013) are too vague in nature and cover too many species to confidently make claims about rates of noncompliance so they have been omitted from this report.

Farmed animal welfare noncompliance in the EU

Unlike voluntary corporate commitments, legal commitments are usually mandatory and enforceable by third parties. Despite the apparent energy to develop new animal welfare laws in the EU, there is a possibility that too little attention is paid to developing robust systems to ensure these standards are met in reality. The EU ban on (narrow) veal crates appears to now be fully complied with, as is the ban on conventional battery cages for egg-laying hens, but only after half of EU countries missed the deadline for application of the latter. Compliance with the partial ban on sow stalls of three to four member states is still being verified seven years after the deadline,[8] and the majority of countries were late. As many as 90% of pigs in the EU are still subject to tail docking and ~35% on average per country are not provided with sufficient enrichment materials despite requirements being in place for more than two decades (Nalon and De Briyne, 2019). The Commission’s own evaluation revealed that 66% of chickens raised for meat are kept in the higher stocking densities allowed despite the required additional animal welfare conditions not being reported or met. While the Commission reports that compliance with the transport regulation is close to 100%, investigations by animal welfare organisations consistently find high levels of noncompliance, especially when it comes to ensuring that high standards are met for live animals that are transported outside of the EU (CIWF, 2018). Problems in the humane slaughter regulation with the use of the derogation for slaughter without stunning and inadequate stunning procedures have also been noted (ECA, 2018).

Even countries generally regarded as having high national animal welfare protection often fail to meet legal requirements. For example, in 2012 (before the majority of EU species-specific laws went into force), Dutch authorities published reports for broiler, pig, calf and cow farming showing compliance with animal welfare laws (national and EU) to be on average 67%, but when animal groups Dier & Recht and Varkens in Nood included laws that are not inspected nor reported on, the compliance level was at maximum 5% (Dier & Recht & Varkens in Nood, 2012) and subsequent reports have continued to document high rates of violations (Dier & Recht & Varkens in Nood 2014, 2016; Varkens in Nood, 2016). This is a country which ranks among the top in terms of legal provisions for animal welfare on the Animal Protection Index, so other EU countries are plausibly in a worse situation. However, the number and level of precision of regulations is not indicative of high concern for animals as some countries could have zero pieces of legislation on animal welfare and treat animals much better in practice. While EU laws are transposed into national law (translated from general EU goals into specific national laws and regulations), in this report we do not make claims about whether noncompliance with EU laws is better or worse than noncompliance with national laws.

Is the EU an exception regarding compliance with animal welfare laws or is compliance with animal welfare laws very low everywhere?

Countries in the EU are likely not alone, nor the worst in the list, in noncompliance with animal welfare laws but may appear so simply by being an area of the world where there are a lot of animal welfare laws to potentially violate. A 2009 overview of animal welfare in 49 developing countries found only 19 had some kind of legislation concerning animal welfare and/or animal protection (concerning pets, farm animals and/or wildlife) (Bracke, 2009). The overview’s general impression was that enforcement is particularly strict in regions where economic dependency on biodiversity and wildlife is great (e.g. some African countries) or when biosecurity measures need to be followed up for international trade purposes (e.g. South East Asia). In most regions however, it appears that the level of legislation as well as its enforcement is positively related to the country's material wealth; many poorer countries simply do not have the manpower and resources to enforce any rules.

India is one example where high costs, unreliable power sources, and under resourced or nonexistent domestic regulating authorities impede application of animal welfare laws (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2018, 2019). Despite a general consensus that conventional battery cages are illegal according to Indian animal welfare laws, in 2017 they still appeared to be widespread (Bollard, 2017). The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act has not been amended or updated since it was first created in 1960 and consequently, the fine for violations is 50 rupees, which is less than $1. [9] According to Indian law, animals cannot be legally slaughtered outside of licensed slaughterhouses, but this law is not enforced or regulated for the slaughter of chickens or goats. Animals are regularly slaughtered in live markets, and most of the slaughterhouses that do exist are not legally registered (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2018, 2019).

However, even in wealthier countries we also see problems. The USA has two major federal animal welfare laws relating to farmed animals (the 28 Hour transport Law, and the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act). Limited enforcement mechanisms and inadequate financial deterrents undermine the application of the humane slaughter provisions (Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, 2010; Matheny & Leahy, 2007), which specifically exempts poultry. The 28 hour law, prohibiting lengthy transport of live animals without rest, has rarely been enforced and the fine per violation ranges only from $100-$500 per shipment (Matheny & Leahy, 2007). Animal Welfare Institute has produced numerous reports that show while federal and state humane slaughter enforcement actions rose during the Obama administration, and especially in reaction to investigations by animal welfare groups, the absolute level of enforcement is low in comparison to other aspects of food safety enforcement and varies significantly by state (AWI, 2010, 2017a, 2017b, 2019, 2020b, 2020a).In neighbouring Canada, despite the historical public support for government enforcement of humane slaughter, there is little public reporting to indicate the success and consistency of such enforcement (NFAHW, 2012, 2019). The EU has both greater resources to enforce rules and also more rules to enforce than other regions.

Is animal welfare an exception regarding compliance in the EU or is compliance in other areas in the EU equally bad?

The academic literature is replete with assertions that noncompliance with EU level legislation in general is common, from transposing the EU laws into national legislation to implementing the laws in practice (Toshkov, 2012; Borghetto & Franchino, 2010; Hartlapp & Falkner, 2009; König & Luetgert, 2009; Falkner & Treib, 2008; Kaeding, 2008; Falkner et al., 2007; Haverland & Romeijn, 2007; Thomson et al., 2007; Mastenbroek, 2005; Sverdrup, 2004; Knill & Lenschow, 1998 is just a snapshot of the literature). However, it is actually quite difficult to get a reliable picture of the true rates of noncompliance in the EU. Many studies use quantitative data on the timely transposition of directives into national law, which does not cover the incorrect implementation or application of laws. Other studies use implementation and application reports prepared by consultancies or academics but, understandably due to the resources needed for such work, these studies often only cover a limited number of member states, time periods, and policy sectors.

A dataset on the number of judicial warnings for legal violations brought by the EU against member states (1978-1999) found 35% were due to member states formally transposing EU directives into national law on time, but failing to implement and enforce them subsequently on the ground (Börzel & Knoll, 2012). The Commission’s own recent numbers are that 41% of pending infringement cases are due to incorrect application of directives and regulations. Agriculture appears to have lower rates of noncompliance compared to environment and taxation, but the EU Commission does not disaggregate animal welfare policies specifically from general agricultural policies when presenting this data. The European Court of Auditors (ECA) estimated that violations of agricultural compliance standards appear to range from 21% - 29% in the period 2011 - 2015, with 50% of violations related to the keeping of animals, however this only covered a subset of animal welfare requirements (ECA, 2018, 2016).[10]

The main argument that the EU does not have a noncompliance problem points to the decline in the number of judicial cases against member states from 1,332 in 2007 to 800 today. However, if the cases of noncompliance brought to courts do not constitute a “random sample” of all instances of noncompliance, such a bias in the data would also bias the findings on the causes of noncompliance. A survey of experts’ assessment of which member states violate EU law most and least is in line with the commission’s infringement data, with France, Greece, and Italy being considered the main laggards and Denmark, Finland, and Sweden the compliance leaders, although this was conducted before the major animal welfare laws came into force (Börzel & Knoll, 2012).

Who is working on this problem?

Animal welfare groups consider enforcement to be a problem. Dier & Recht and Varkens in Nood, animal welfare groups in the Netherlands, have highlighted the lack of enforcement by Dutch authorities and pointed to better enforcement protocols developed by Wageningen University. The Swedish group Djurens Rätt, operating in a country with above average animal welfare standards in the EU, has highlighted that in addition to private financial issues of farmers, the lack of enforcement and controls is a major reason for noncompliance due to the limited percentage of farms that are inspected per year and the low penalties applied for noncompliance.[11] The EU acknowledges itself that enforcement of legislation has been insufficient (ECA, 2018) but is only now evaluating its 2012-2015 Strategy for the Protection and Welfare of Animals. Vier Pfoten also thinks enforcement is a huge problem, but highlights that trade dynamics are the most important factor.[12] EuroGroup for Animals places a greater emphasis creating new and revising existing laws so that they are easily enforceable in the first place. However, according to an Animal Charity Evaluators report on the allocation of movement resources in general, influencing policy and the law, including improving the implementation or enforcement of existing laws is relatively neglected within the effective animal advocacy movement.

Why does the EU have noncompliance issues?

The wider EU political science and legal literature has suggested a number of theories to explain noncompliance in general, not specific to animal welfare laws. There are three major sides in the debate: those who argue the main factor is the degree of “misfit” between the existing legislation in member countries and the new legislation proposed by the EU (Knill & Lenschow, 1998); those who argue there are “cultures of compliance” which are related to the legal traditions and administrative capacity of the state (Börzel et al., 2010; Falkner & Treib, 2008; Falkner et al., 2007); and those who argue that the number of actors in the system with veto powers (legislatures, regulatory agencies, autonomous regional governments) primarily defines compliance (König & Luetgert, 2009). Each of these theories might imply different actions to improve compliance. A “misfit” perspective might suggest focusing on incremental improvements to narrow the gap between countries before setting a floor with EU standards. A “cultures” perspective offers fewer opportunities for action because it suggests that compliance with animal welfare standards is unlikely to improve without larger structural changes to historically noncompliant countries like Italy. A “veto player” perspective could highlight specific actors that need to be targeted (agricultural ministers, the farming associations, consumers, retailers). Unfortunately, these theories are contradictory and also suffer from using different outcome measures and sample sizes: some measure how late standards were adopted, some measure whether they were transposed into national law, and others attempt to measure how well these laws were implemented in practice (Hartlapp & Falkner, 2009; Kaeding, 2008; Haverland & Romeijn, 2007; Thomson et al., 2007; Mastenbroek, 2005). This would be a good area for a follow up study.

One may start from the position of why would those working in animal farming ever comply with costly improvements to animal welfare that may put them at a competitive disadvantage compared to cheaper lower welfare products? There are various disincentives that can lead to lack of compliance, including a lack of understanding of the sometimes complex rules, financial costs, cost-benefit considerations, pressure from lobbies, a lack of administrative infrastructure, the burden of paperwork, or a lack of incentives as the cost of compliance might be disproportionate in relation to the level of penalties applied (Börzel & Buzogány, 2019; Escobar & Demeritt, 2017; Tallberg, 2002).

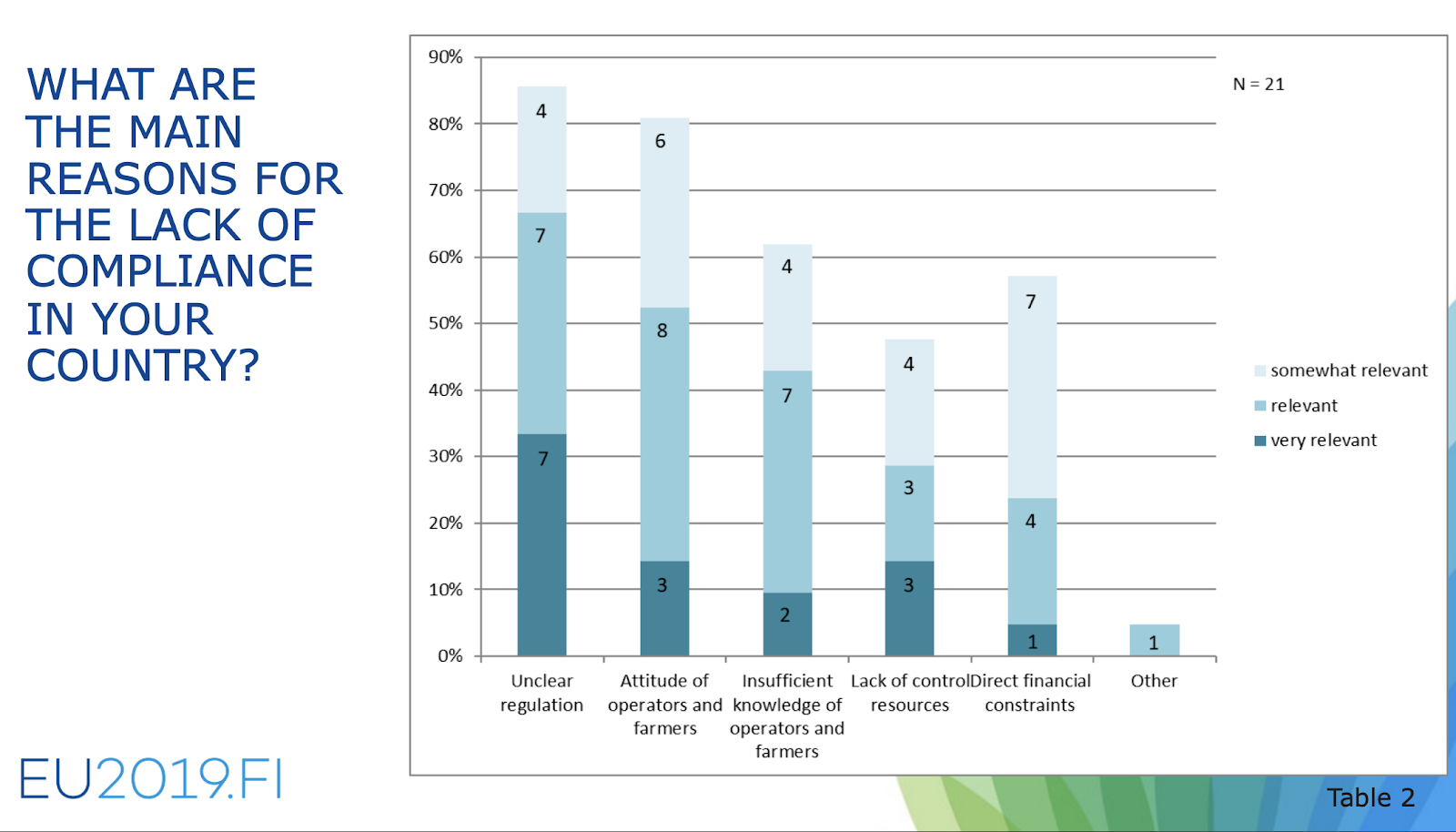

According to a 2019 survey of Chief Veterinary Officers[13] from EU member states (see figure below), unclear regulations and farmer attitudes are the most relevant reasons for noncompliance in animal welfare (Council of the EU, 2020). After reading various reports from EU audits of national inspections systems these farmer attitudes appear to be that farmers believe that other producers are not following the rules, that farmers do not understand the purpose of the legislation, or they see the proposed measures as incompatible with industrial farming.

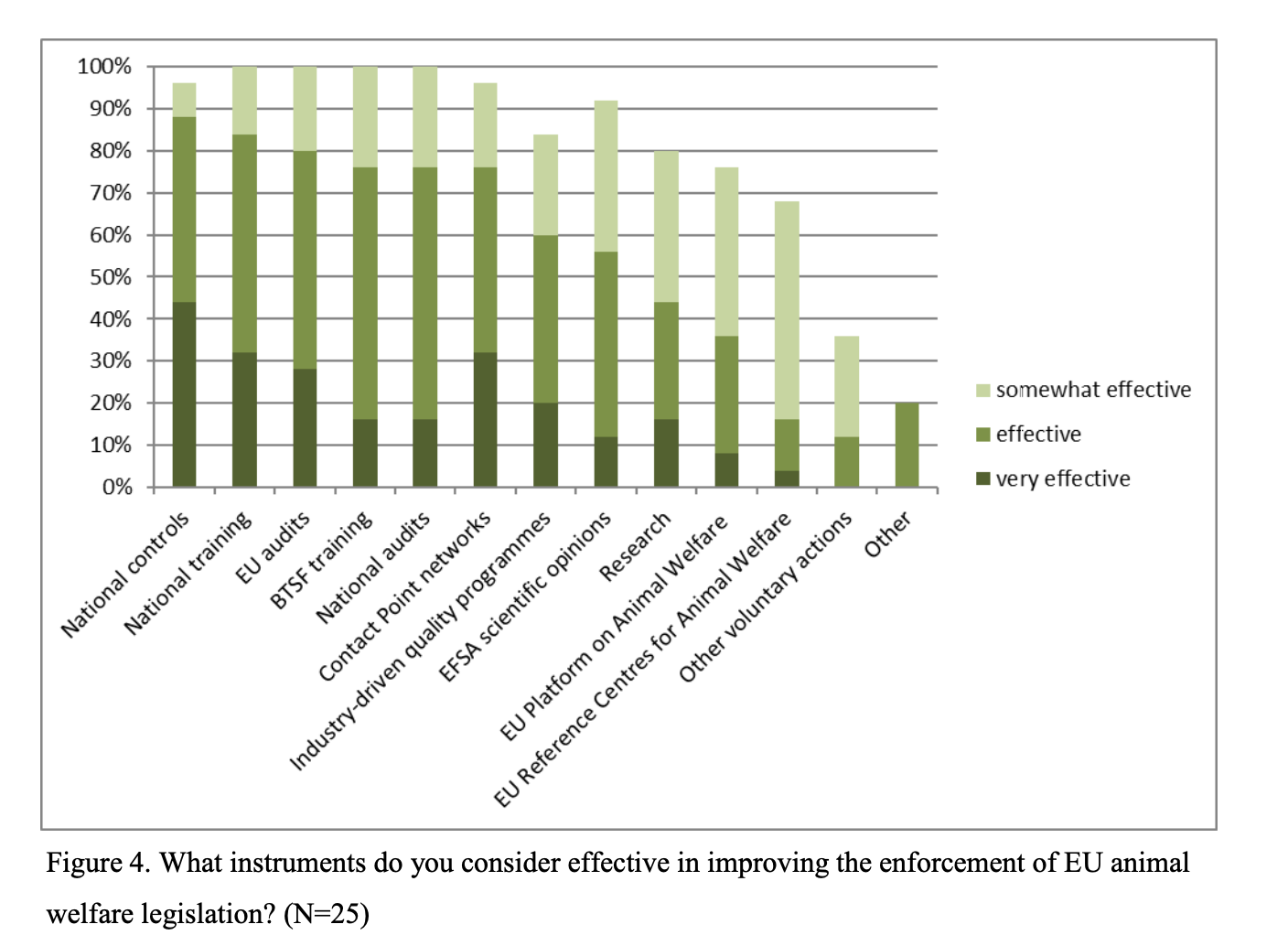

The next obstacles are insufficient knowledge, financial constraints, and “lack of control resources”, which refers to inspections (EU Platform on Animal Welfare, 2019).[14] The same survey showed which enforcement methods were considered to be effective tools (see second figure below), such as national inspections (88%), national audits (76%) and EU audits (80%) (Council of the EU, 2020). Enforcement barriers are, in reality, about failures of member states to properly apply and enforce EU law.

This mostly mirrors a 2013 survey of representatives of national and regional governments, NGOs, think tanks, farmers, farm unions, slaughterhouses, and the processing and breeding industry. The study highlighted knowledge transfer, production costs, public concern, weak inspection frequency and sanctions, and collaboration between government, agri-business, and NGOs as the bottlenecks and supportive measures which determine compliance (Bock et al., 2014).

The EU compliance system

In general, the Commission enacts a directive that member states are entrusted to translate into national laws that define how the directive will be implemented and the Commission conducts audits to check that member states are enforcing the law. The EU Commission is required to make a report to the the heads of state and ministers of member states every 5 years and to make proposals on the progress of legislation. Member states are required to carry out inspections and they report their findings to the EU Commission. Veterinary experts may be dispatched by the EU Commission to make inspections of facilities in member states and audit the national inspection services.

The EU utilises a "management-enforcement ladder": a twinning of cooperative and coercive measures that, step by step, improve states' capacity and incentives for compliance. Increasing enforcement generally involves higher penalties and higher chances of being caught, while increasing management involves transition periods, education about animal welfare practices, and financial incentives. For example, a carrot used is to increase the payments that farmers receive for exceeding minimum animal welfare requirements, while a stick is reducing these payments or issuing fines. We here class the rungs in this management-enforcement ladder as “information”,“transition periods”, “incentives”, “inspections”, “infringements”. This is simply a stylised categorization of a range of activities and tools that are often overlapping and not necessarily concatenate, and are not relevant in each case. Alternatives to Commission enforcement, such as the delegation of direct monitoring, investigation and sanctioning powers to a specialised EU agency (Collins and Earnshaw, 1992), which increasingly takes place in a narrow band of subject matters such as financial markets, medical technologies, aerospace and fisheries (Scholten, 2017), have so far failed to materialise in animal welfare. One should again remember that a major goal of members of the EU is to protect the interest groups in their countries, of which the animal farming industry may be powerful depending on the country and that animal welfare requirements are often treated as a consumer information or food safety issue.

Information

The most common concern expressed in the Chief Veterinary Officers survey above was unclear regulation. The wording of EU legislation directly or indirectly concerning animal welfare often does not conform with the scientific meanings of these terms. This can lead to confusion and variation in interpretation of the legislation (Lundmark, 2016; Lundmark et al., 2014; Lundmark et al., 2013). Measures that are unambiguous and easily verifiable by one-off inspections of fixed assets such as housing systems plausibly start off from a position of being more likely to succeed than requirements related to the daily management of the animals (feeding, watering, handling, light, etc.). Unlike the design of facilities (cages, stalls), the latter are dependent on the way animals are treated on a daily basis, which requires more inspections, more paperwork, more changes to the behaviour of farmers themselves. That said, changing to new housing systems often requires costly retraining and management practices too.

Where such ambiguities arise, the Commission seeks to offer guidance documents and training to both farmers and inspectors on proper implementation and application. The effectiveness of such instruments is limited, which is perhaps not surprising since these are recommendations only, and anything that implies going above legal standards can only be voluntary. [15] There are usually no more than 100 participants per Commission training event - many of whom are lobby representatives - so the audience is limited compared to the number of European farmers concerned. It is difficult to assess how much of the content of these events is made available online and how widely is it read. The Commission has now begun setting up “Reference Centres” on certain animal species[16] to conduct research into animal welfare indicators and best practices, and to disseminate this knowledge. It is unclear what impact these networks of research institutions will have, but animal groups we spoke with are somewhat sceptical of how influential the provision of this science-based information will be.[17]

Animal welfare laws rarely include specific enforcement mechanisms, instead deferring to general principles outlined elsewhere. The transport regulation does include enforcement provisions (article 26) requiring a member state that finds a breach to notify the member state of departure and those that granted authorisations or certificates. The purpose is to prevent recurrence of these breaches. However, the required notifications are rarely given in a systematic way and even where they are, the member state who receives the information rarely act on them in such a way as to prevent recurrence of these breaches. As a result the same breaches are repeated year after year (CIWF, 2018). This suggests that even when enforcement provisions are included in the directly applicable legislation there is still the problem of a lack of political willingness to use them effectively.

Transition periods

EU legislation often gives producers a lengthy phase out period when a particular production system is banned is to ensure that producers will, before the ban comes into force, reach the point where their existing infrastructure and equipment come to the end of their working life and would in any event need to be replaced. While we shouldn't expect to see majorities of producers phasing out existing infrastructure and equipment earlier than economically necessary, if producers and authorities take the law seriously we should see evidence that they are not installing new soon to be illegal infrastructure before the deadline. Transition periods have been acknowledged by the Commission to not be very effective however (SEC(2012) 55 final). While long transition times before deadlines or grace periods after deadlines have passed may send a positive signal to industry that they will be given time to prepare and for details to be worked out (Knill and Tosun, 2009; Perkins and Neumayer, 2007), it is just as likely to provide industry with time to lobby for watering down the provisions or extending the deadline.

Incentives

In economic terms, animal welfare is not very important for farmers’ production decisions because while no costs are attached to the degradation of animal welfare, as long as the welfare level does not affect productivity, costs are often associated with improving animal welfare. The EU provides some financial instruments to compensate producers for higher production costs and to incentivize reform. A discussion of the problems in this system and how to reform it merits a much more substantial discussion than can be provided here, so instead we lay out the basics of how the system works today and some issues specific to animal welfare.

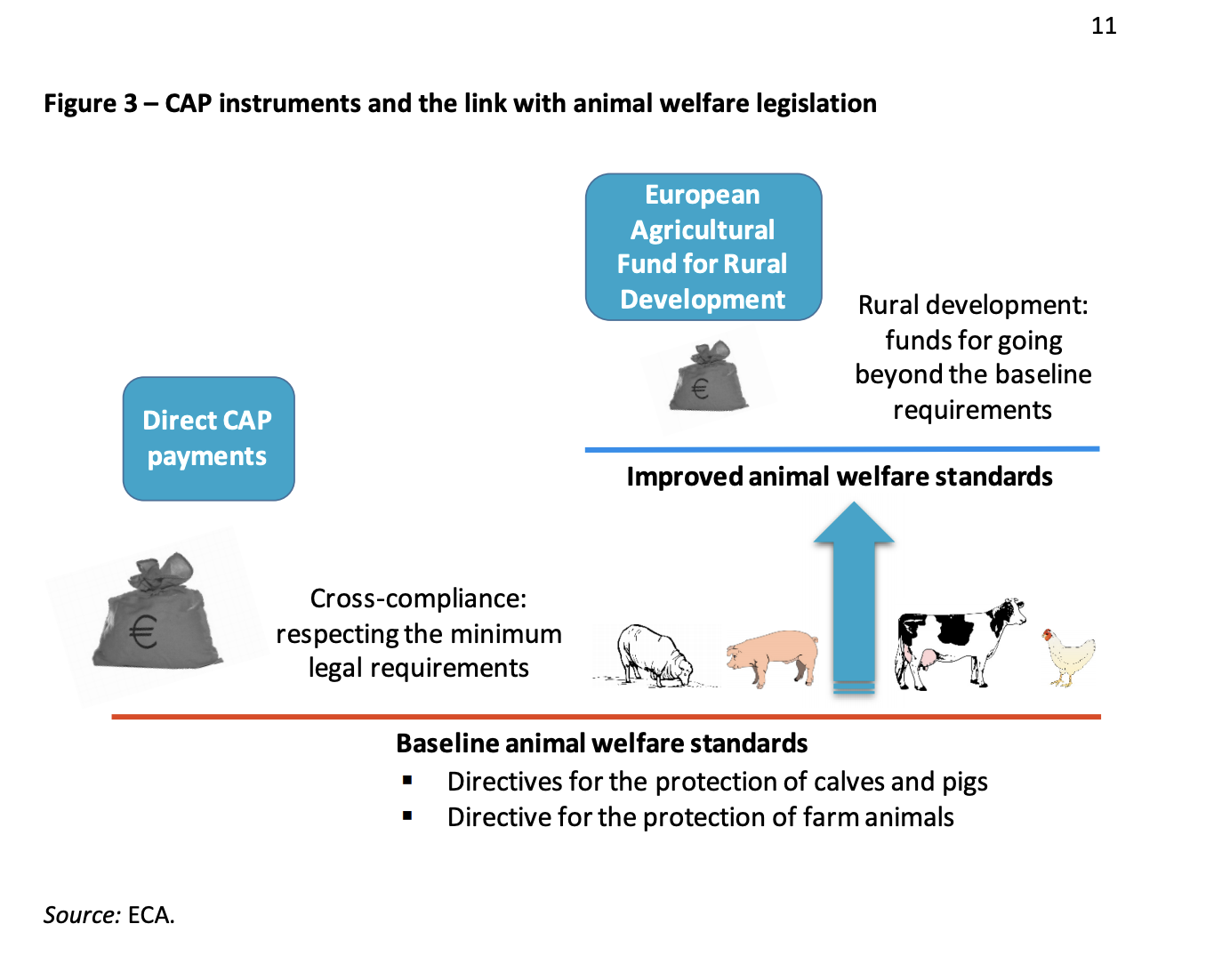

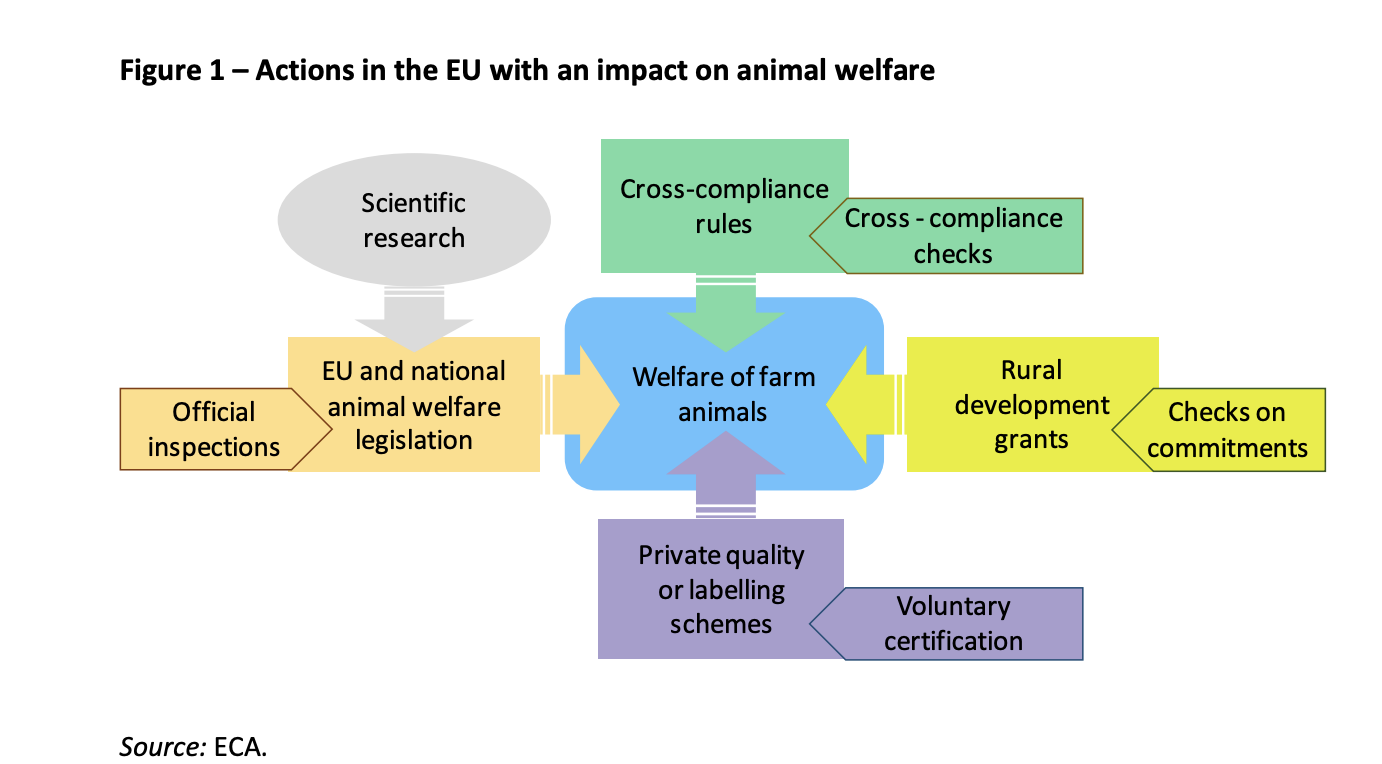

The figure below, from a European Court of Auditors report, illustrates the two main economic pillars: Common Agricultural Policy) (CAP) payments are provided directly to farmers primarily to ensure the economic viability of farms but can be reduced if found to be in breach of minimum standards, and additional “Rural Development Funds” can be applied for by member states and farmers to go beyond these minimums (ECA, 2018). Together direct CAP payments, Rural Development Funds and market related expenditure account for ~37% of the total €160 billion EU budget (EC, 2020b).

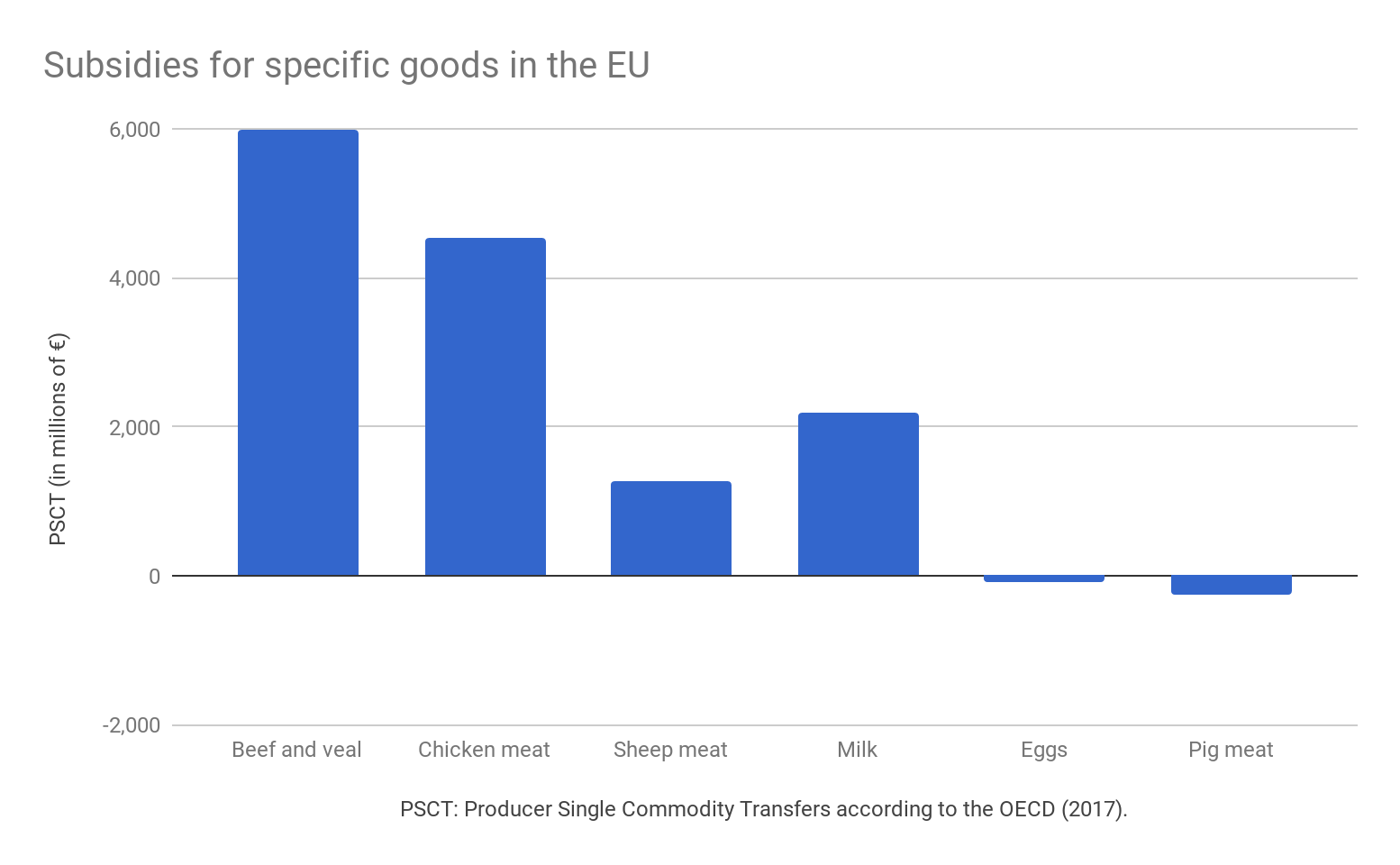

The main purpose of CAP direct payments is to provide income support to farmers to compensate them for the public goods and services they provide (minimum of €196 ($227 USD) per hectare), not to directly support animal welfare. Few countries make use of the CAP tools to address animal welfare objectives[18]. In fact, CAP payments have served to produce large quantities of animal products at an artificially lower cost, encouraging higher consumption. Rethink Priorities researcher Daniela R. Waldhorn calculated how much money the EU transferred to farmers for the production of specific animal products in 2016, as shown in the figure below.

CAP payments (subsidies) are not distributed evenly, such that 80% of the €12.9 billion in payments go to 20% of the 125,000 farms (Gogłoza, 2019). You can see how much a farm in your country received at farmsubsidy.org. Most CAP payments are linked to farmers’ compliance with basic rules for food safety, animal health and welfare, and good agricultural and environmental conditions. However, compliance is not an eligibility condition for payments but only triggers administrative penalties when not respected. “Small” farms (small being defined differently across countries) are not included in these figures as they are not subject to administrative penalties if they do not comply with cross‑compliance obligations. In some countries such “small” farms make up over 50% of farms in a country.

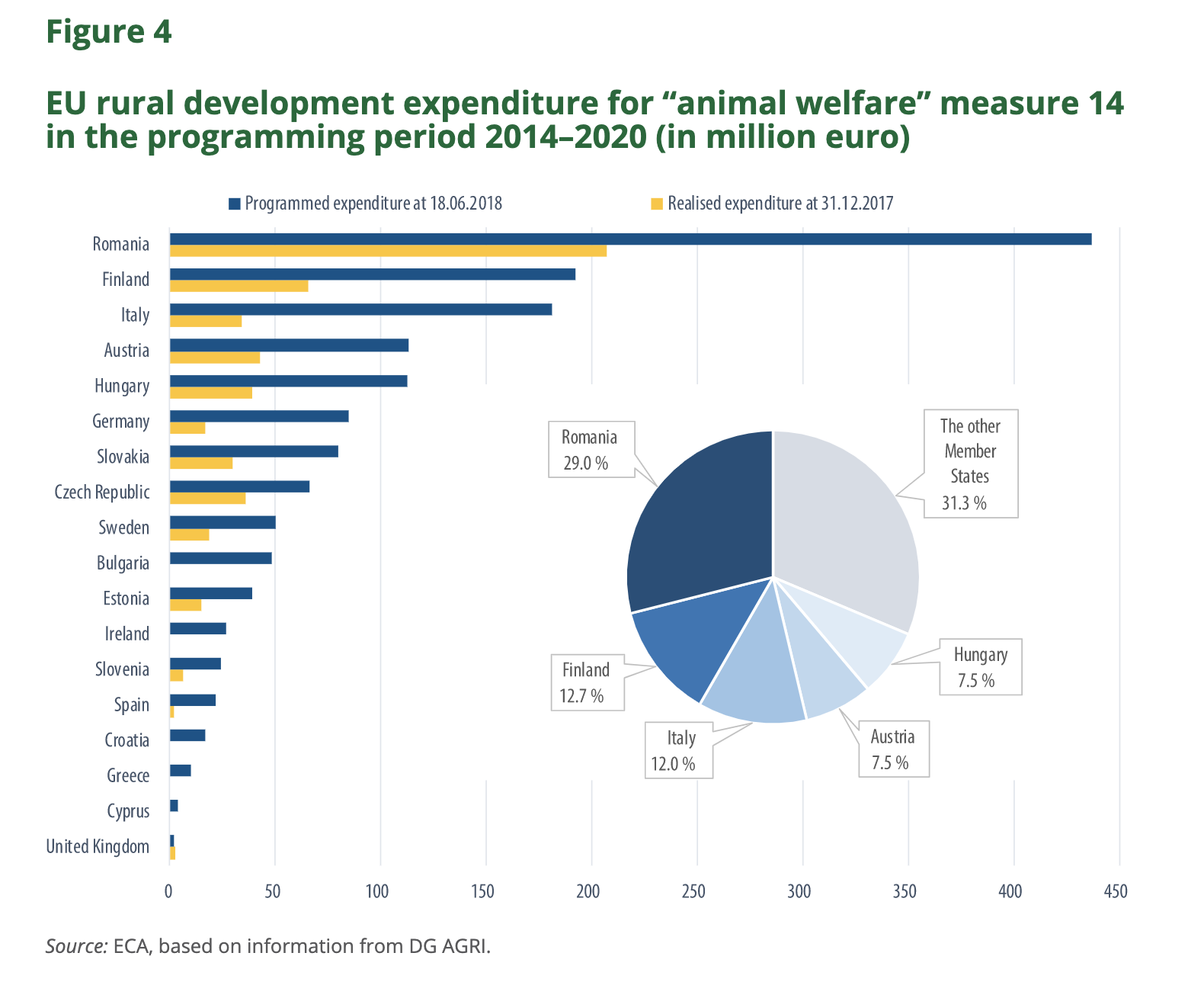

Member states also can draft Rural Development Programs to draw on funds from the EU based on a set of measures set out by the EU. Countries themselves define the conditions applied to the measures included, which may include Measure 14: "promoting food chain organisation, animal welfare and risk management in agriculture", but it is not mandatory. These programs are then approved by the Commission. For the 2014–2020 period, the funds allocated to the animal welfare measure of the Rural Development Funds account for €1.5 billion (1.5 % of the total EU rural development funds), an increase from the €1 billion in 2007–2013 (ECA, 2018). 10 member states have not used the rural development funds for animal welfare in the most recent reporting period. It may be understandable that countries omit animal welfare conditions from their programs altogether because there may not be enough of a market for farmers to transition to higher welfare standards and maintain competitiveness regardless of transition costs being covered, or that countries simply have other priorities when designing these programs. However, even among those who do include animal welfare conditions in their programs a lot of the available money appears to simply be left on the table, as can be seen from the difference in programmed and actual expenditure in the figure below (ECA, 2018). One plausible explanation is simply that some countries do not have the institutional capacity to effectively apply for and distribute these funds in what is often a huge and complicated bureaucratic system.

When Rural Development Funds are drawn upon, the Commission does not check whether the money is going to farmers who were planning to implement such animal welfare provisions anyway even without this financing, nor does the department of the Commission responsible for dispersing funds check with the department responsible for noncompliance to ensure stated requirements are met (ECA, 2018). In fact, the ECA concluded that the impact of €2.5 billion for animal welfare payments between 2007 and 2020 is not able to even be assessed because the Commission does not have information on the expected or actual results and impact of rural development funds provided for animal welfare. It also seems likely to be the case that EU funds are dispersed by national governments not as an incentive to comply with standards, but as standing payments to favoured interest groups, and so do not actually serve as much of an incentive (Evans & Pegg, 2019; Gebrekidan et al., 2019). Due to Covid-19, the deadlines for EU countries to submit annual reports on the implementation of their Rural Development Programs have been postponed so we do not know when the most up to date data will be available.

Inspections

Member states translate EU rules into obligations at the farmer level and verify whether these obligations were respected via national inspection agencies. Member states are responsible for putting in place systems which prevent, detect and correct instances of noncompliance, carrying out on‑the‑spot checks, applying penalties and recovering unduly paid funds from farmers who have breached the rules. Except in the area of competition law, the EU has only indirect enforcement powers - the supervision of the application of the law by public authorities (Rowe, 2009). The Commission is obliged to verify that the member states carry out their responsibilities via the Commission Directorate General's Health and Food Audits and Analysis unit (which we will refer to as DG SANTE for simplicity), previously called the Food and Veterinary Office (FVO), and to apply financial corrections when it is found that their systems are deficient. The ECA concluded this cross-compliance system had not been an effective policy (ECA, 2016).

DG SANTE has relatively few resources to ensure standards are being met. While the opportunities for noncompliance have increased over time due to an increase in the size of the EU and the number of laws, the Commission’s enforcement capacities have not. Brussels’ bureaucracy has always been comparatively small, equaling the administration size of a European city of 1 million people such as Cologne (Börzel & Buzogány, 2019). In 2011 it was reported that there were only nine full time equivalent employees for performing audits and inspections (EC, 2011b), and it may be as low as three individuals today.[19] The coverage of farms is around 1% of agricultural holdings making up 250 days of on-site visits per year (EC, 2013a). To put this in context, if authorities would focus exclusively on the dairy sector, visiting 1% of farms annually, it would take them 100 years to visit all dairy farms in the EU (DG SANTE, 2017). An analysis of DG SANTE audits has shown that the EU has used different standards for compliance inspections in Northern and Southern European countries (Zonderland & Enting, 2006). DG SANTE can point out problems in national inspection services but not correct for noncompliance itself, so it is unclear if increasing DG SANTE visits would necessarily provide better results.

Enforcement of EU legislation falls under the competence of member states, who are better resourced and placed to inspect their own farms than the Commission agencies, but there appears to be a wide variation in the frequency of national inspections, even in high animal welfare countries like Germany (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft, 2015).[20] Some states do not check farms according to risk indicators, even when performing risk-based inspections is an EU legal requirement. [21] Member state authorities usually delegate the responsibility for carrying out the risk analysis for farm and transport inspections to local authorities. None of the member states visited by the ECA by 2018 had put in place systems to check the existence, quality and implementation of the local risk analyses (ECA, 2018). Due to an exemption on inspecting small farms and different definitions of what constitutes a “small” farm, in Eastern European countries where “small” farms make up the majority of the sector, most go unchecked.[22] A 2016 DG SANTE report on broilers found most member states (65% of those studied, which accounted for 80% of the annual EU production of chicken meat) did not have effective and complete systems to monitor, collect and assess information regarding on-farm welfare at the slaughterhouse level (FVO, 2016). Part of the problem in monitoring compliance appears to stem from a delegation of cross-checking between two levels of inspection. Official inspections by national veterinary services verify the correct application of European Union animal welfare rules while cross-compliance inspections follow up with the application of penalties.

While some states like France carried out “dual purpose” inspections by paying one visit to the farmer and using an integrated checklist of both breaches and penalties, others such as Poland had no formal cooperation between the two authorities. The number of staff available in the competent authorities of the member states to carry out animal welfare inspections has been substantially reduced in some member states in order to cut costs. This may be in contrast to the market-driven mechanisms in Europe, such as voluntary retailer schemes, which may be enforced better than national laws because the retail companies have more people per producer to do the enforcement than the government has (Broom, 2017) and because corporations are subject to regulations on consumer information (such as false advertising), hence corporations come under a much wider scope for inspections.

The Commission and national authorities can also receive information from citizens and NGOs who flag possible cases of noncompliance. This complaint mechanism has developed into the “chief source for detecting infringements” (EC, 2003). Such NGO data is not considered official data and therefore cannot officially provoke an audit, but it may unofficially do so. For example, the Commission contacted Spanish authorities in light of noncompliance revealed by farm visits carried out by Compassion in World Farming ( Borg,2013 ), a guilty court verdict for Greece may have been instigated following investigations by Compassion in World Farming and other animal welfare groups showing widespread breaches of the slaughter regulation (CIWF, 2009), and the European Parliament debated and published a report on pig tail docking on the basis of petitions[23] filed by Dyrenes Beskyttelse (Danish Animal Welfare Society), and Humane Society International. In 2012 the investigation by Dier & Recht and Varkens in Nood mentioned above led to a debate in the Dutch House of Representatives and questions in the European Parliament (Dier & Recht & Varkens in Nood, 2012). The results of the investigation were also confirmed by a report by the ECA. Dutch politicians discussed the abuses, but no major improvements were made at the time. A second report in 2014 was also discussed in the Dutch House of Representatives alongside clear recommendations. Subsequently, budget and staff cuts to the Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority were marginally reversed, but still insufficient to ensure adequate coverage of animal farms.

Due to Covid-19 there has been a reduction in the overall number of physical on-the-spot checks and leeway has been given for the timing of inspections (which are often unannounced). This is in order to minimise physical contact between farmers and the inspectors carrying out the checks. Member states will be able to use alternative sources of information to replace the traditional on-farm visits, such as the use of satellite images or geo-tagged photos to prove that infrastructure investments took place, however, this is not useful for inspections which must be carried out inside buildings. This could mean fewer compliance checks will be conducted during the pandemic, but it could also spur innovation and streamlining of the inspection process.

Infringements

On the national level, payments to farmers, transporters, organisers, and slaughterhouse owners/operators can be reduced, or administrative penalties applied, if they are found to be in breach of legislation. However, national penalties are often not proportionate to the seriousness of the violations. The penalty for the same infringement can vary from 0% to 20% depending on the member state (ECA, 2016).[24] The Commission cannot tell member states what penalties they should impose, but is responsible for ensuring that penalties are “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”. At present penalties are often too low and applied too infrequently to be effective or dissuasive. Eurogroup for Animals has proposed that since sanctions could play an important role in improving enforcement of EU rules, they should be harmonised at the EU level (EC, 2013b, n. 12.2). This option was discarded in EU discussions as it was argued it would either 'under' or 'over' compensate costs, and developing uniform cost models for each infringement would be a very burdensome exercise (EC, 2013b, n. 2.2.1.1.).

In cases that are brought to the attention of the Commission, it can launch (or threaten to launch) infringement proceedings that would bring a member state to the Court of Justice of the EU and possibly incur financial sanctions (e.g., up to tens of millions of euros per semester of persistent noncompliance, plus a compensatory bulk sum, and the legal costs).[25] Emphasis is placed on early compliance through negotiation, with court action and financial penalties meant to constitute exceptions and last resorts. The advantages of a centralised judicial system are clear: it is comparatively well funded and commands a large and experienced legal staff. Across the entire spectrum of EU legislation, the court sides in more than 90% of closed cases with the Commission against the member states (Börzel & Buzogány, 2019) and the Commission can use the threat of escalation in negotiations with member states, who often back down before a court judgement in as much as 86% of all cases (Toshkov, 2016). This may be due to non-financial costs such as damage to political reputations.

However, infringement procedures are not regarded as the means to bring the best possible enforcement, given disincentives like the huge delays between first warnings and final court decisions as well as the costs per case (Pelkmans et al., 2013). The average number of pending infringement proceedings against an EU country is 25, and the average duration of infringement proceedings is 38 months, while it takes on average 28 months between the delivery of the Court’s judgment and the closure of the case confirming that the member state has complied with the judgment (EC, 2020a). Moreover, the Commission does not pursue all infringements it is alerted to and has wide discretion about using the infringement procedure, even where a member state’s breach of obligations is obvious, and retains the right to terminate the procedure at any point regardless of the member state’s compliance with its demands (Craig & Burca, 2011; Eliantonio, 2016). The number of complaints submitted to the Commission has been rising, but only 4.8% of these led to further investigation by the Commission (De Bernardin, 2019). This is not explained by the use of alternative informal complaint mechanisms (like EU Pilot)[26] instead as complaints there are rising too despite a downward trend in cases through these alternatives too (De Bernardin, 2019).

A study of infringement cases (1978-1999) found that in half of the policy sectors, there are only a handful of infringement proceedings (Börzel & Knoll, 2012). In the sectors internal market, environment, enterprise, industry, and agriculture, by contrast, member states commit large numbers of violations. Italy is the compliance laggard in virtually all policy sectors while the Scandinavian member states, the UK, and the Netherlands have consistently good compliance records. A more recent study (2003-2014) found some countries, like Italy, Greece, in the past France, more recently Luxembourg, make up every year a disproportionately big share of all infringement proceedings (Toshkov, 2016).

With regard to animals specifically, there have been 71 cases against 24 member states since 2002, 30 of these cases concerned animals used for scientific purposes, 13 were concerning animal health requirements in the trade of dogs, cats and ferrets, 13 concerning the housing of laying hens and 11 concerning the housing of sows.[27] 62% of closed cases came after the Commission gave just a formal notice of warning, without further steps being initiated. Only 4 countries have been referred to the court for breaching animal-related laws.[28] According to the Commission, these procedures were successful in achieving compliance with the rules (however, without providing detail) (ECA, 2018).The ECA reviewed the Commission’s 2012 to 2015 audit reports on animal welfare in 5 member states, the related action plans for dealing with noncompliance, and their follow-up, and found that these member states addressed almost half of the Commission’s recommendations in two years or less (again, without providing more detail) (ECA, 2018).

However, there also seem to be consistent instances of these “negotiations” and infringement proceedings lasting years or being “resolved” without action being taken by the noncompliant member states. According to the Commission, delays to enforcement procedures in the past have been due to the large number of member states involved (ECA, 2018). The largest number of countries that infringement proceedings were started against at one time regarding animal welfare was 14. This may be concerning given that on the issue of tail docking alone, under the current circumstances, the Commission would have to launch over 20 infringement procedures (considering the majority of member states are evidently noncompliant) (Nalon & De Briyne, 2019). The unwillingness of the Commission to bring such cases against them may mean member states adopt a lacklustre approach to EU animal welfare.

Another legal route is to use national administrative courts to bring action against national inspection authorities and noncompliant producers in order to uphold or revise animal welfare standards, as national courts are increasingly becoming an area for private enforcement (Hofman, 2019). National infringement actions often come with suspensions of activities by the alleged transgressor, unlike EU legal action. There has been relatively little comparative work on how successful this approach is. For the moment it appears that public interest group litigation before national courts to enforce key provisions of EU directives is in principle able to remedy compliance problems, but only if a set of demanding conditions is met (Slepcevic, 2009;Stephenson 2005). There are few examples of this method (although see a case won by the animal welfare group Wakker Dier in regard to provision of newly hatched chicks with food and water under the general farm protection directive). From reading audits conducted by DG SANTE of national inspection services it is clear that national authorities often fail to apply rules as stated in the directive so there may be many promising opportunities for litigation.

Case studies

We now look at how these mechanisms have worked in practice in the species-specific animal welfare directives in the EU. The restrictions on battery cages, sow stalls, and veal crates were all agreed in a similar timeframe and followed a similar structure of over a decade transition period for existing housing infrastructure to be phased out. The restrictions on pig tail docking and broiler stocking density required changes to daily monitoring and environment of animals. These were all species-specific which made it easier to get a sense of the number of animals affected, compared to the general farm protection directive and regulations on transport and slaughter which cover a wide range of animals and harder to validate conditions (like what constitutes unnecessary suffering).

Conventional battery cage ban

Conventional battery cages are systems to house chickens used for eggs production. The animals are tightly stacked together in barren cages in a closed building with forced ventilation and with or without a lighting system. In 1999, EU countries agreed that no new conventional battery cages should be installed after 2003 and to phase out existing conventional battery cages in farms with more than 350 hens by 2012, but allowed alternative “enriched” cages which have minimum space requirements per caged bird, as well as perches, litter, and a nesting box (directive 1999/74/EC).[29] These allow slightly more movement to hens who are caged collectively, but still limit natural behaviours such as exercising. Note that we do not here make a judgement that so-called enriched cages offer hens a life worth living or the degree to which they may be better than conventional battery cages without these furnishings.

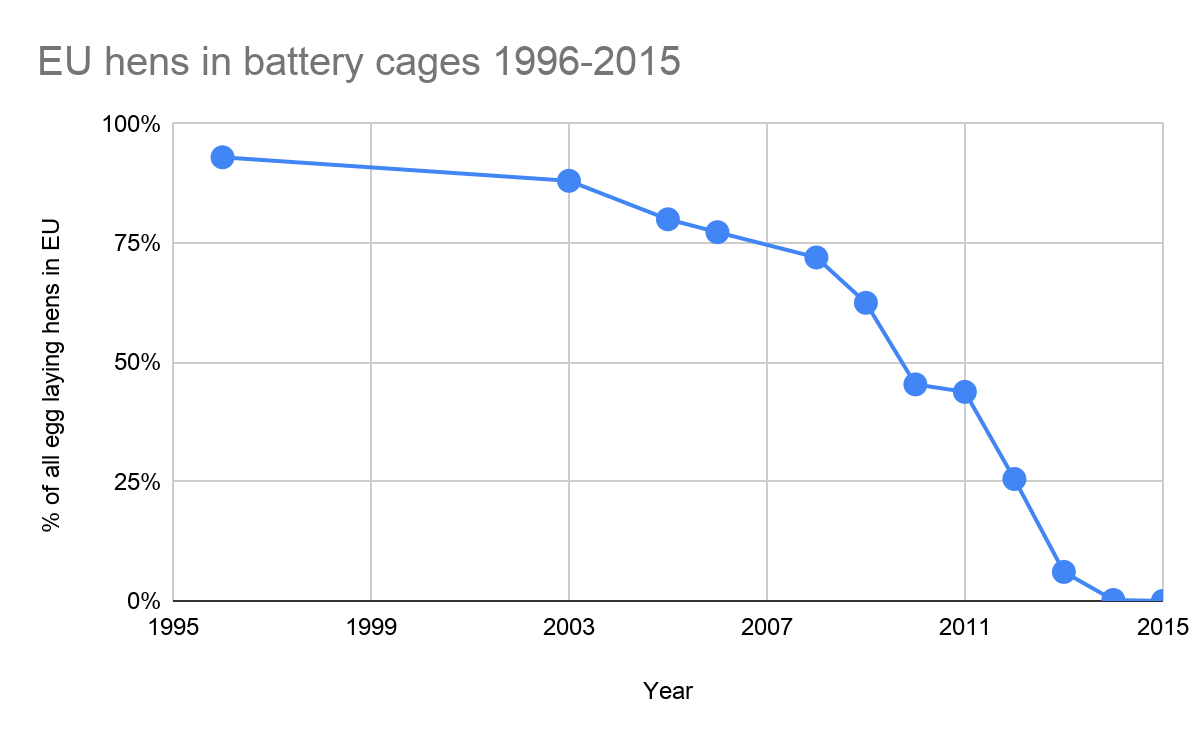

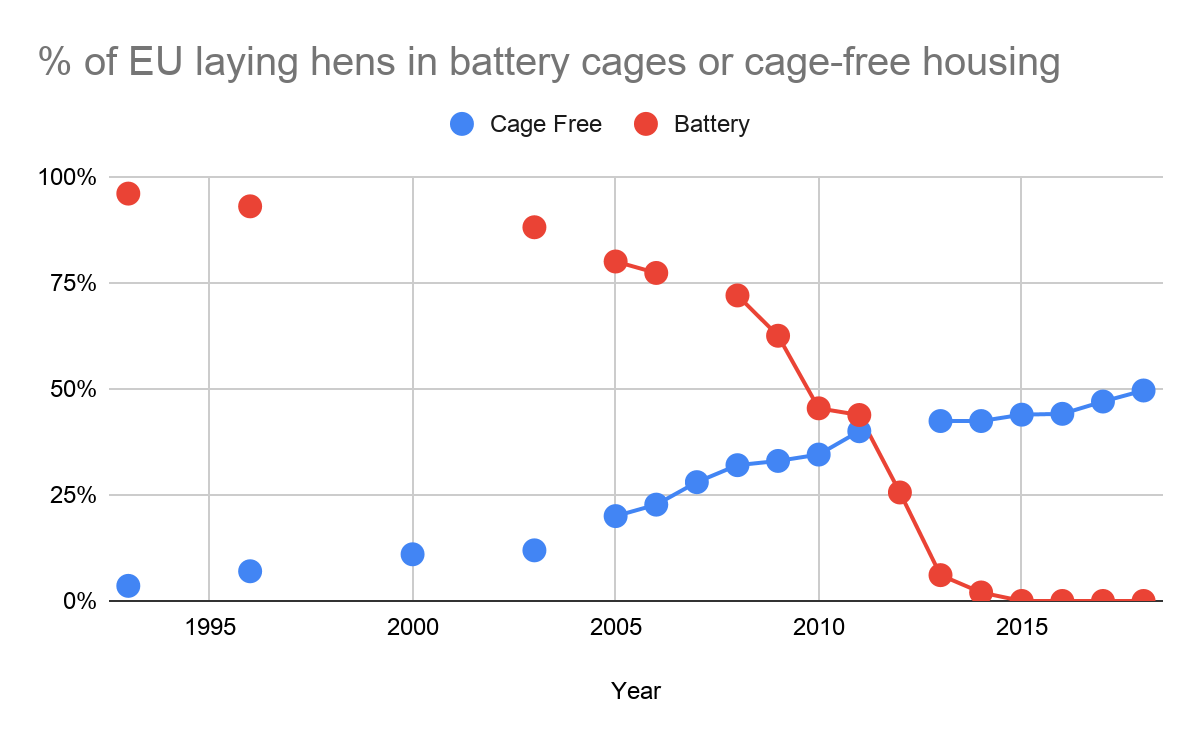

In 1996, 93% of the 271 million hens in the EU were housed in conventional battery cages (EC, 1998). In an ideal world following the letter of the law automatically, the expected number of hens in such cages would’ve been 0 in 2012. It was estimated in 2006 that there would still be at least 150 million hens kept in conventional battery cages by 2012 (FAWC, 2007). In 2010 this estimate was revised to be 100 million hens still being kept in battery cages by 2012 (Agnew, 2010). In reality that number was estimated to be 46–84 million (14–30% of total EU egg laying hens) by the time the deadline for the ban came along,[30] which suggests something changed that sped up the transition in the interim for 64–104 million hens (assuming the estimates in 2006 and 2010 were based on reliable data). 13 member states were found to be in breach of the ban in 2012, but by 2013 there were only allegedly 800,000 hens in conventional battery cages (0.2% of total EU egg laying hens) (EC, 2014) and by 2014 there were 0, in farms with more than 350 hens (EC, 2015).

There is not very reliable year-on-year data for the percentage of EU hens in conventional battery cages unfortunately. However, using the limited data available, which includes projections by official sources and numbers reported by media sources, there is a clear downward trend. Note that in the 10 years between 1996 and 2006 there was a 17% reduction in conventional battery caged hens, while after 2010 there were similar or higher rates of reduction within a single year. This is slightly confounded by the addition of numerous countries into the EU who had majority battery cage systems in 2004.

The rather sudden drop in the share of hens in conventional battery cages within a matter of months—and if not, then within a couple of years—does raise the question as to whether the numbers were fudged. It certainly would not be the first time a member state has massaged data to meet EU requirements (Carassava, 2004). However, the significant increase in shell egg prices in the EU following the deadline,[31] the drop in egg production,[32] and the decrease in the number of hens[33] in this period does suggest that countries really were transitioning.[34] A similar trend occurred in Germany prior to its own 2009 national ban on conventional battery cages (O’Keefe, 2012a).[35] A confounder is that the EU entered a debt crisis in this period and so we may have expected to see falls in production and some farmers going out of business anyway. The reality of the transition was of course made possible by the mass culling of layer hens by noncompliant producers and the closure of many farm operations.

One might ask why did countries take so long to act, if indeed it only took them a few years to abolish the practice? On the other hand, a farmer transitioning before the existing conventional battery cages reached the end of their normal productive lifespan and before a competitor did so would mean incurring costs and risking a competitive disadvantage years before it was necessary. Maybe we should instead ask why there was progress at all before 2012.

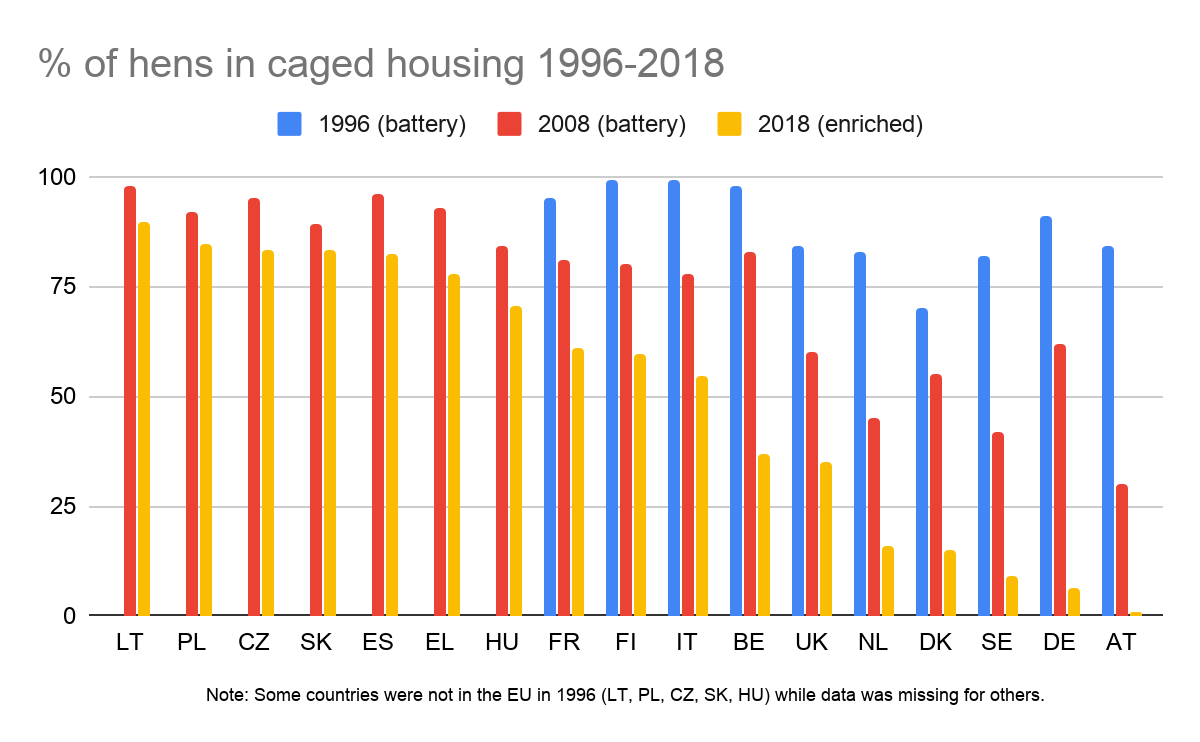

In 2008, 278 million hens were in cage systems, and only 20 million of these (7%) were in enriched cages (Poultry Site, 2009). One can see below that the countries which had the lowest share of their hens in conventional battery cages in 2008 did not simply have the same share in “enriched” cages by 2018, but rather increased the share of hens in cage-free systems. On the other hand, countries which had the highest percentage of their hens in conventional battery cages in 2008, and thus the largest change to make to meet the 2012 deadline, still have a caged-housing system for the majority of hens 10 years later. This is despite an assumption that because enriched cages are more expensive, it makes it less profitable for producers to keep hens caged rather than cage-free.

We can also see below that the share of chickens in cage-free systems increased dramatically from the mid 2000s. This was both the time when a mandatory egg production labelling law (Regulation (EC) No 589/2008) came into place (egg packs must carry one of the following terms: ‘free range eggs’, ‘barn eggs’ or ‘eggs from caged hens’), but also when the EU expanded to a set of Eastern European countries with very high shares of conventional battery caged hens. Since these new Eastern European countries that joined in 2004 still had high shares of hens being kept in battery cages in 2008 and enriched cages in 2018, they cannot account for the increasing share of hens in the EU that are cage-free. So the change in EU cage-free hens must almost entirely be driven by those countries shown above as early adopters of cage-free systems (Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, UK). The mandatory labelling may then have played a large role in increasing the share of hens in cage-free systems but it is unclear what role it played, if any, in increasing the share of hens in enriched cages rather than conventional battery cages.

So whatever X factor (retailer-led product differentiation, public concern, corporate campaigns, political leadership, egg labelling) led to the increase in cage-free hens in the mostly northern countries (Denmark, Sweden, UK, Germany, the Netherlands) still hasn't occurred in the rest.[36] This at first glance appears to offer good evidence that legislation created improvements for millions of hens in Southern and Eastern European countries that would not otherwise have come about due to the factors driving cage-free housing in the other countries.[37] The question for those interested in compliance is to what extent, if any, additional actions beyond simply enacting legislation increased the speed or scope of compliance with the legislation.

Information

Initially, in 1999, the Commission had agreed to confirm which housing systems would be acceptable and give a definitive date for implementation of the ban by January 2005.[38] However, this did not come until January 2008 (EC, 2008), after campaigns to keep the ban from Compassion in World Farming and members of the European Coalition for Farm Animals (ECFA) (CIWF, 2008). Ambiguity about the commitment to the standards at first glance seems to have been a powerful force in leading many countries to miss the deadline. A 2004 report provided to the Commission details that in almost all EU countries there were virtually no hens in enriched cage systems and this stemmed from uncertainty about whether and in what form the laying hens directive would be confirmed (AGRA & CEAS, 2004). A UK Farm Animal Welfare Council report specifically noted that the delay in the Commission’s report “has meant that the industry has not felt sufficiently confident to make the commercial decisions necessary to invest in alternatives to the conventional cage system” (FAWC, 2007).

Transition period

Existing conventional battery cage buildings were assumed to have a productive lifespan of 30 to 40 years and so even a 13 year transition period would cause substantial costs for egg producers who had recently installed new conventional battery cages. Many farmers were simply reluctant to make the investments and incur the costs of compliance early on, only to find themselves undercut by competitors who did not and could sell cheaper products. The biggest enemy of farmers are not animal groups, but their neighbours. Many were hoping the egg industry would successfully lobby for the ban to be delayed. However, the lateness of the Commission’s report put huge demand on the manufacturers of compliant cage systems that likely simply did not have the capacity to deliver and install cages so that every country could be compliant by the deadline.

Contrast this to the situation of Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden which instituted earlier national bans and were already in compliance with the EU law by 2012.[39] It is also apparent that countries that were transitioning earlier were able to benefit from a market of noncompliant countries by selling conventional battery cage hardware to producers waiting to transition later (AGRA & CEAS, 2004). However, even if in 1999 the Commission had made a binding commitment to maintain the deadline and given clear information on acceptable alternatives to conventional battery cages from the beginning, why would farmers have transitioned any earlier than absolutely necessary?

Back in 2004, industry was already assumed to make the switch to enriched cages as close to 2012 as possible (AGRA & CEAS, 2004). Note again that in 2008 many countries had upwards of 70% of hens still in conventional battery cages when the Commission confirmed that the 2012 deadline would not be postponed. This gave countries four years to comply. Given the productive lifespan of approximately 13 months for egg-laying hens, in order for a flock to be fully compliant by the deadline birds would need to have been housed in compliant cages no later than the end of 2010. DG SANTE reports from 2012 reveal that after 2009 many countries began training programmes for farmers and compiling registries of housing systems.

However, the number of countries found to be noncompliant, and decreases in the number of laying hens in certain countries between 2011 and 2012 suggests many producers were still putting new birds in conventional battery cages after 2011 suggesting they had no intention to comply with the law. Some countries were quite persistent in their efforts to find a way out, continuing to allow new conventional battery cages in 2011, even though this was supposed to have stopped in 2003.[40] In 2005, pressure was already being applied by several southern European countries to extend that deadline until at least 2017 and even as far as 2022 (FarmingUK team, 2005). Poland spearheaded an effort even in 2010 for the Commission to grant extensions until 2017 (Berkhout, 2010), but already compliant member countries, pressure from animal groups on these (mostly southern and eastern) soon to be noncompliant countries, and a resolution from the European Parliament (EP, 2010) contributed to the Commission sticking to the deadline. This might suggest that pushing a key number of countries to adopt their own earlier national bans could create the internal pressure the Commission needs to hold fast on deadlines. This is a hypothesis a future report will discuss in more detail.

Incentives

Given that many member states had more than 70% of their hens in conventional battery cages in 2008 (as shown in the chart above) and the EU entered a financial crisis in the years before the deadline, it may not be surprising that many countries missed the deadline. Higher production costs have been cited as one of the major obstacles in adhering to EU layer welfare standards before the crisis (Van Horne & Achterbosch, 2008; Van Horne et al., 2007; Van Horne & Bondt, 2006). Eggs were viewed as an excellent source of affordable protein and governments in poorer countries (such as Romania, where the average family income was €250 per month) were reluctant to enforce the ban so as to avoid creating further volatility and potential food shortages locally (Chippindale, 2010). The low market demand for higher welfare eggs in some member states had been a commercial disincentive for early adoption for producers (House of Commons, 2011), while in countries that transitioned earlier (Germany and Austria) retailer schemes were already in place to facilitate consumer awareness of and demand for higher standards for hens.

In refusing requests to extend the deadline, the Commission specifically proposed to the Polish authorities that they use the existing possibilities within the rural development programmes for bringing housing systems into line with those standards by that deadline. It is certainly the case that some countries offered transition assistance (such as Spain and Portugal (Hanson, 2012) France,[41] Italy, [42] Belgium[43]) and EU Rural Development Funds for upgrading the rearing systems for laying hens were made available, but only some member states (like Ireland[44] and Bulgaria[45]) used them for better compliance with the legal requirements. The reason for the apparent reluctance of member states to draw on this fund and tie payments to animal welfare measures is unclear, but suggests there was money being left on the table (CIWF, 2011b; ECA, 2018). And even countries where producers did make use of financial assistance did not uniformly meet the deadline.

Inspections

The Commission was reluctant to deploy its limited inspection resources on checking compliance until two to four years before the deadline (the latest time by which countries could have put hens in conventional battery cages and still be in compliance by 2012). The data provided to the Commission by member states at the end of 2010 was “far from optimal” in the words of Joanna Darmanin, Head of Cabinet, Directorate General Health and Consumers, but the Commission has no power to penalise those member states that had failed to provide the required data, and simply requested sufficient information about the state of play before April 2011.[46]

Commissioner Dalli said inspection teams were ready to go “all out” from January 1, 2012 with increased surveillance targeted at noncompliant member states based on submitted lists of compliant and noncompliant producers (EC, 2011a). Reviewing the DG SANTE reports from 2012, nine countries were visited after the deadline,[47] though not all of these were listed as noncompliant so it is unclear whether the inspections themselves or fear of inspection actually induced compliance, if they did at all. Reportedly inspections of the 13 member states that missed the deadline were postponed because they would only have proved what these countries had freely admitted (FarmingUK Team, 2013).

DG SANTE reports detail how inspections by some national authorities were stepped up in the years immediately before and after the deadline. This included intensive monitoring, enforcement notices, and good cooperation between inspection authorities. In the case of Romania, enforcement was achieved solely through inspections without the need for sanctions, while in Bulgaria a large number of inspections was not enough to ensure compliance until sanctions were later imposed. It is also notable that in countries instituting earlier national bans, such as Sweden, the inspection systems were strengthened too (AGRA & CEAS, 2004).

Animal welfare groups also highlighted noncompliance with the ban. Noncompliant producers were found in 2012 by Association for the Free Rearing of Hens (L214) (Lewis, 2012) and Vier Pfotens (PW Reporters, 2012), while Compassion in World Farming demonstrated that operators in Greece were still flouting the ban in mid 2014 (Clarke, 2014).

Infringements

Between 2008 and 2010, DG SANTE audited 20 member states and examined the state of enforcement of the ban by national authorities (EC, 2011c). Whilst all member states had mechanisms to do so, some had not imposed sanctions on noncompliant producers or had imposed fines that were not financially onerous (ranging from the low hundreds of euros to tens of thousands).[48] It was worthwhile for producers (in Italy and Poland) to pay the fine because the profit was so large from the sale of the additional eggs produced by overstocking. In other countries there were unwritten agreements not to issue sanctions to farmers (Hungary) or a reluctance to impose large fines that would be contested in court (Malta, Romania). Subsequent DG SANTE reports in 2012 and 2011 show that some countries had increased the fines to dissuasive levels or imposed other financial penalties (Bulgaria, Netherlands, Slovenia), but others continued to issue only low penalties (Latvia, Italy). Other countries took more forceful measures such as using police to ensure illegal eggs went to rendering plants, reclaiming profits resulting from overstocking in unenriched cages, and threatening and practicing the impounding and culling of hens.

Apparently the Commission had been in a state of denial. It was quoted as saying “we are not prepared to contemplate that people will not have converted. We think they all will” and that only after member states had submitted data which demonstrated the state of noncompliance will they “start to kick it into high gear and have a strategy on how to deal with it” (House of Commons, 2011). The Commission then had few options on the table, including delaying the deadline, creating a new labelling code for “illegal” eggs, increasing inspections and beginning infringement proceedings, and an internal trade ban.[49] The Commission faced pressure to stick to the deadline from already compliant countries and from animal groups, like Compassion in World Farming’s “Keep the Ban” and “the Big Move”[50] campaigns in addition to a network of animal welfare groups in the European Network for Farm Animal Protection. Legitimising illegal eggs through a new egg label struck most as counterproductive. Despite WTO rules not providing for a ban on imports due to animal housing systems, an intra-community trade ban did appear to occur. The Czech Republic and Bulgaria effectively banned Polish egg imports because of the latter’s failure to conform (Poultry Site, 2012a, 2012b), and the UK reached a voluntary agreement with business not to sell illegal eggs[51] and on the use of UV light to scan for illegal egg imports (Gov.uk, 2011; Poultry Site, 2011).[52] EU countries informally made a non-binding 'gentleman's agreement' that national authorities would ensure all noncompliant eggs were broken, processed, and only used within the country of origin for processed products.

Once the deadline passed the Commission was quick to issue warning letters to the 13 countries not enforcing the ban (and giving them a six month grace period). By the end of that summer all but a few member states were compliant. Compassion in World Farming’s “Defend the Big Move” campaign highlighted continued breaches by Italy and Greece after the deadline had passed. In 2013, the Commission brought Italy and Greece to court, where around 20 million hens still remained in conventional battery cages. Both were found guilty in 2014 but in the end only had to pay legal costs, not financial penalties (CIWF, 2014; WATTAgNet, 2014) (possibly due to the financial crisis). The cases against them were not formally closed until October-November 2015 suggesting battery cages may have remained in use there for almost 4 years after the deadline.

Impact of enforcement

How many hens would have “automatically” ended up in compliant housing systems simply from the law existing, absent further enforcement actions? We can clearly see that there was indeed pressure by industry to postpone the deadline and producers were still being granted and installing the soon to be illegal cages even past the latest possible time one could do so and meet the deadline, suggesting they hoped to continue raising hens in battery cages for quite some time after 2012, and Poland had asked for a 5 year postponement. Approximately 33 million birds were culled 2011-2012,[53] and since it is unlikely producers would intentionally have begun raising birds they expected to be slaughtered before reaching the end of their productive lifespan we can suggest that at least these 33 million would have remained in battery cages if not for enforcement (or threat of enforcement) of the ban. A further 46–84 million hens were still in battery cages after the deadline passed and either reached the end of their planned productive lifespan, were transferred to other housing systems or were culled by 2014. Up to 20 million of these hens remained in conventional battery cages in Greece and Italy up to 4 years after the ban despite escalating EU legal action. When Compassion in World Farming exposed illegal Greek cages in July 2014, it suggested the producers were planning for another 18 months of cage production (taking them up to January 2016) (Clarke, 2014). It seems plausible some if not most noncompliant producers in these countries were simply allowed to remain noncompliant until the end of the productive lifespan of their existing battery cage installations. The other 26-64 million hens outside of Italy and Greece then may have remained in battery cages for a similar time if not for some effect from the intra-community trade ban, pressure campaigns from industry and animal welfare groups, increased inspections, increased fines, and infringement proceedings launched by the Commission. It seems plausible then to think 33 million to 97 million hens (33 million culled before the deadline plus the upper estimate of 64 million post-deadline) would not have automatically been in compliant housing simply from the law existing. This is very roughly 9%-27% of the 365 million or so egg-laying hens in the EU per annum at that time.

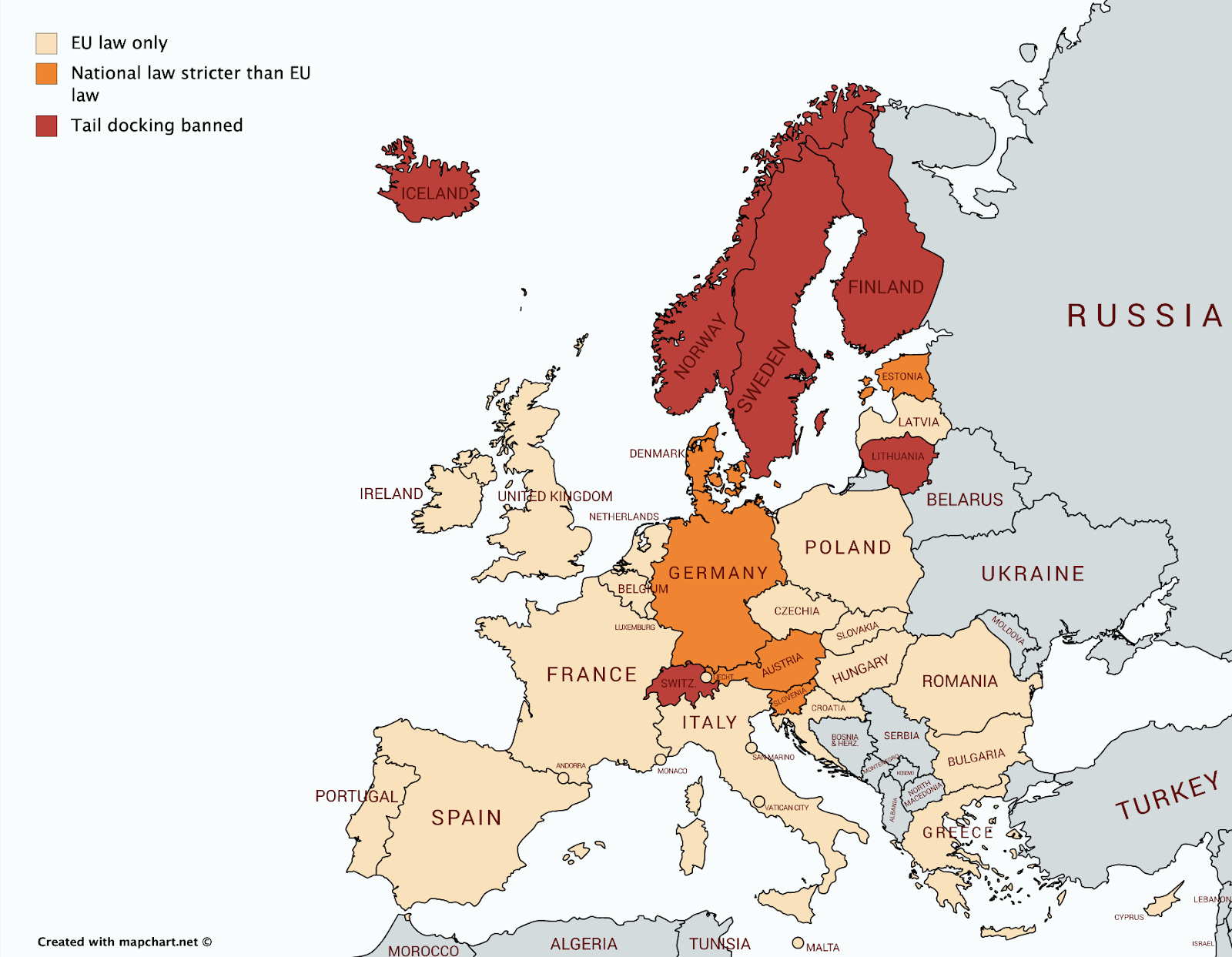

The pigs directive

The first EU-wide rules on pig welfare were established in 1991 (directive 91/630/EEC) and enforceable since 1994 to curb the practice of tail docking, which is commonly used to prevent pigs biting each other’s tails. This was followed by a 2001 directive (2001/88/EC) requiring a phase-out of the use of individual stalls for pregnant sows by 2013, except for the first four weeks of gestation and one week before farrowing. The pigs directive (2008/120/EC) consolidated minimum standards for the protection of pigs, the prohibition of the tethering of sows, banned routine tail docking, established requirements for environmental enrichment for pigs and sought to improve the flooring surfaces on which pigs are kept. We take the sow stall restriction and tail docking restriction in turn.

Sow stall restrictions

The 2001 directive (2001/88/EC) laid out that no new individual stall housing systems were to be installed after 2003 and existing infrastructure was given a ten-year transition period until early 2013. From 2013, all pregnant sows in the EU were to be housed in loose group systems rather than individual stalls from four weeks after “service” up to seven days before expected farrowing

In 1998, the average percent of breeding sows in 13 EU countries in individual stalls was 45%, but all the major producers used this system for more than half of their pigs. The use of stalls was actually increasing as producers switched to stalls in advance of an EU ban on the use of tethers due to come into force in 2006 (CIWF, 2000).[54] By 2010, in Germany and Denmark, both large pig producers, 50%-80% of pig producers were estimated to be noncompliant, with other countries assumed to be in worse positions (Schulze zur Wiesch, 2010). The Commission also claimed that it had learned the lessons from the problems then unfolding in noncompliance with the conventional battery cage ban, and an implementation plan included “all the tools available at EU level are being used to put pressure on the member states so they comply by the legal deadline” including data collection, stakeholder meetings, providing information about financial support, training veterinarians, and preparatory work for infringements (EC, 2012).

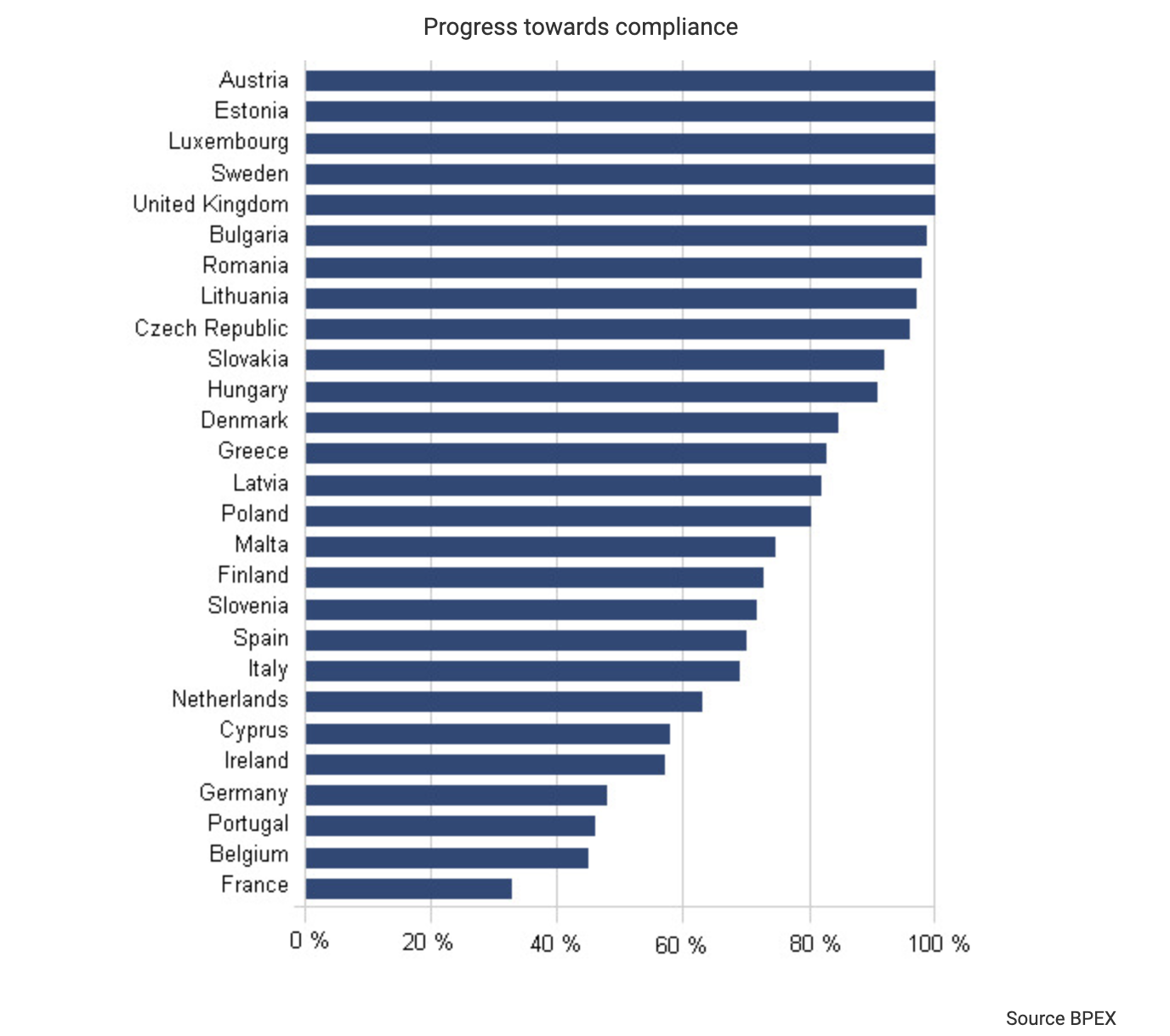

While the UK, Sweden, and Luxembourg were compliant well ahead of the deadline due to earlier national laws restricting stalls, when the January 2013 deadline passed as many as 22/27 countries were noncompliant (see figure below from countdownto1-1-13.co.uk, which was set up by the British Pig Executive to monitor compliance) though ~6 of these countries were at least 90% compliant. Reportedly 2 million to 5 million of the 13 million sows in the EU would be in illegal individual stalls,[55] including ~52-67% of sows in Germany and France which were two of the largest pig producers in the EU.

In February 2013, Commissioner Borg demanded member states to provide regular updates of relevant data and Farm Ministers to apply dissuasive sanctions to noncompliant producers (Pig333, 2013). In the space of a few weeks from December 2012 to February 2013, rates of compliance shot up dramatically by an average of 18% but by more than 30% in some countries. However, the UK National Pig Association (NPA), a trade association for the pig industry, claimed that “some countries such as Italy and Spain have convinced the commission that they are compliant when we know discussions with their own producer groups suggest that’s not the case” (Case, 2013) and a member of the UK National Farmers' Union visited a supposedly compliant pig farm in the Netherlands and discovered that sows were not being kept in groups as required by the legislation (FarmingUK Team, 2013) so it is possible some of these numbers were manipulated.

Transition period

In 2010, the pig industry, and especially Southern and Eastern countries, had sought an extension to the 2013 deadline but was refused by the Commission (PigProgress, 2010; WATTAgNet, 2010). However, even producers in countries with typical higher animal welfare standards, such as Denmark, had been hoping for a delay (SYSADM, 2009). In 2011 it was reported that many producers in the EU had still not even started planning for the transition to “loose” housing systems, with producers in Germany claiming that implementation instructions had not been provided (Abbot, 2011; Schulze zur Wiesch, 2010). In order to comply, farmers could either decrease the numbers of pigs in farms to create more space, make large capital investments to extend existing or construct new buildings in order to maintain the same amount of pigs at the farm, or choose to stop farming pigs altogether. At that stage the conversion was no longer worthwhile for many piglet producers who may have wanted to get out of production in four or five years anyway. Pig herds were reportedly shrinking in the 12 months prior to June 2012 in all main pig producing countries (FarmingUK Team, 2012),[56] and one reason is likely that during the changeover to group housing, many companies no longer invest in new pigs or drop out of the market, so that the inventory drops significantly. Again it seems however, many producers and authorities continued business as usual during the transition period with no serious intention to be ready for the deadline.

Incentives

We found limited to no evidence of financial incentives used to promote the transition. One region in German provided funds for the switchover, but was found to still have noncompliant producers in 2013, (Imhäuser, 2012) while industry associations in the Netherlands were refused financial aid for the less than 10% of producers who were still noncompliant in 2012 due to financial problems or lengthy approval procedures (SYSADM, 2012). Many producers across the EU cited difficulties in obtaining financing as a reason for a lack of investment in compliant housing (The Pig Site, 2011).

Inspections

DG SANTE visited 5 countries in 2010-2012,[57] and found evidence in 4 that compliance would not be met in time and in the one country where authorities were confident compliance would be met (Hungary) it would later be found noncompliant. In April 2012 the Commission was informed by 16 member states that they would be compliant by the deadline (EC, 2012) although Compassion in World Farming suggested the true number was closer to 10 with a few countries not even able to provide data (WATTAgNet, 2012) (in the end only 5 were compliant). Commissioner Dalli informed the Agriculture Council in June 2012 that at least nine countries would miss the deadline. The Commission stated it would only take action after the deadline had passed and it was clear which countries were noncompliant (Abbot, 2012). Belgium, Hungary, Spain and Portugal had not had an inspection to establish that they were compliant by the deadline and none were scheduled for 2013, despite being noncompliant (FarmingUK Team, 2013).