Preventing Animal Suffering Lock-in: Why Economic Transitions Matter

By Karen Singleton @ 2025-07-28T21:55 (+43)

Abstract

This post explores how emerging economic systems could lock in harmful defaults for animals and outlines a research agenda to identify opportunities and begin the groundwork for embedding animal welfare into future frameworks before it's too late.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Ian Andrews, Kevin Xia and Andrew McCallum for thoughtful feedback on an earlier draft of this post. All mistakes are my own.

TL;DR

- Our economic system commodifies ~ 1.6 trillion animals annually.

- This system is being destabilised by many factors including AI, climate breakdown, inequality and institutional decay.

- These disruptions create rare openings to reshape foundational values.

- Industrial capitalism embedded speciesism at scale, new systems could do the same.

- This post outlines a neglected research agenda exploring how to integrate animal welfare into emerging economic frameworks before lock-in occurs.

- It suggests initial directions (such as integrating animal welfare into post-growth metrics and AI governance) and invites feedback on the core framing and strategic priorities.

Introduction: why I’m writing this now

At EAG London,[1] I shared early thinking on how we might guide emerging economic systems to reduce non-human animal suffering. The conversations confirmed both the neglected nature of this intersection and its potential importance. While I wasn’t sure if I was “ready” to share work-in-progress ideas, those discussions reinforced how valuable it can be to surface neglected questions, especially during periods of systemic transition.

This post outlines my research direction focused on how foundational shifts in economic paradigms create both opportunities and risks for long-term moral circle expansion.

Why economic paradigms matter for animals

To understand why economic transitions matter for animals, it is vital to examine the assumptions underlying current EA approaches. Much of EA’s current work implicitly assumes relatively stable economic and institutional systems.[2] That makes sense for near-term tractability. However, if those systems undergo fundamental change, due to AI, ecological breakdown, geopolitical volatility or other factors, then our assumptions about intervention tractability and impact may no longer hold.

Re-examining those assumptions becomes critical during periods of systemic transition, when new norms are embedded in policies, infrastructures and institutions through "value lock-in."

The last major economic transition locked animals out. The next one could too.

We need to hedge across plausible futures

Moral and empirical uncertainty about the future demands intellectual humility when reasoning about the future. We shouldn’t assume neoliberalism will persist indefinitely, nor should we bet on any single alternative model.

This implies a strategic need to hedge across multiple economic trajectories, ensuring that animal welfare survives any transition.

For longtermist[3] EAs, the stakes are especially high. Values embedded during system transitions can shape moral trajectories for generations. If animals are left out now, they may remain excluded far into the future.

The logic of lock in: lessons from AI policy

To better understand the strategic logic of early intervention, we can look to AI governance, a field where timing and value alignment have long been recognised as critical. It offers a valuable parallel for animal advocacy: acting before values are embedded in institutional design is not unique to our cause.

I find the distinction between steering policies and adaptation policies compelling. Steering policies aim to shape the direction of change from the beginning, adaptation policies respond to problems after they arise.

This framework provides a useful clarification:

- We can attempt to steer, to influence the foundational assumptions and institutions being designed right now. Or we can wait and adapt to whatever new economic paradigm emerges, fighting for reforms after the fact.

Examples of early-stage steering include animal-inclusive metrics, shaping AI rulebooks and developing alternative progress measures and testing new policies models. But the line between steering and adaptation is not always clear-cut. Many real-world interventions, such as piloting new governance models or testing participatory approaches, can play both roles: steering when introduced early in the design of a system, and adaptive when used to reform systems already in motion.

Early-stage interventions are never perfect. Steering policies can be blunt tools, and their outcomes hard to predict but the risks of inaction are greater. Once key assumptions are embedded, they tend to resist change.

Just as longtermist AI governance seeks to avert lock in of misaligned objectives, so too must animal advocates work now to prevent speciesist assumptions from becoming embedded in the foundations of future systems.

A new research space: animal welfare meets economic transition

Currently, few EAs are examining this intersection between economic systems change and animal welfare. One rare example focuses on post-work futures, while another offers important framing on paradigm shifts and their implications for strategic planning in animal welfare. Similarly, Sentience Institute’s[4] work touches adjacent areas but doesn’t directly map systemic economic transitions.

The gap isn't that EA ignores systems thinking, it's that economic systems analysis rarely includes animals, and animal advocacy rarely considers economic transitions. Bridging this divide could reveal high-leverage interventions that are robust across uncertain futures.

This seems like a highly neglected and plausibly tractable space for early-stage exploration, especially under frameworks like differential progress and moral longtermism.

Avoiding false choices: long-term strategy, not a substitute

I’m not talking about replacing near-term work, I’m suggesting complementing it with forward-looking strategies that ensure moral progress survives transitions. If AI eliminates factory farming jobs, or climate change collapses traditional food systems, advocacy that doesn't adapt may lose its relevance.

This is about future-proofing moral progress, not abandoning near-term wins.

Equally important, this approach reveals leverage points we might otherwise miss: emerging economic and governance systems will likely include policies with no explicit animal focus that could nonetheless create substantial benefits for animals. If we recognise these opportunities and advocate for the right design choices.

For example, in conversations at EAG, I mentioned to several people preliminary research[5] suggesting that four-day work weeks (a policy that could emerge across various economic frameworks) impacts on red meat consumption. This illustrates how seemingly unrelated systemic changes might create unexpected leverage points for animal advocacy.

Why now: a critical window for foundational change

We are living through a convergence of multiple, reinforcing crises. Economic instability, AI disruption and ecological breakdown, compounded by energy constraints, climate shocks, rising inequality, and speculative capital are not isolated challenges, they’re interconnected forces pushing us into a meta-crisis; a tangle of systemic failures across ecological, economic and ethical domains.

This convergence is undermining the stability that our current growth-oriented economic system depends on. While this doesn’t guarantee collapse or radical rupture, it does create a window for structural change and moral renegotiation.

This matters because economic systems are not neutral. They’re designed, through deliberate policy choices, and they can be redesigned. “Every system is perfectly designed to produce the results it gets”[6] and current design has entrenched assumptions about markets, growth and what counts as value.

Factory farms illustrate this perfectly. They aren’t aberrations; they are the result of an economic system that treats animals as production units while “privatising profits and socialising the costs” of environmental damage, public health risks and animal suffering.

If we take value lock-in seriously, as many EAs do in AI and moral circle expansion, then the next logical step is to ask: what would it mean to act before the next system is built? Economic paradigms shape who matters and what gets counted. If animals are excluded from today’s future-shaping frameworks, they may remain excluded for generations.

This convergence of crises creates a crucial moment to surface neglected values, like the moral consideration of animals, before new systems are locked in. To understand why this window of opportunity matters for animals specifically, we move onto current suffering.

How current systems entrench suffering

Animal suffering isn’t just a product of consumer demand or weak regulation. It’s structurally embedded in our current economic system. Economic paradigms don’t just permit exploitation; they shape who gets included in our moral and policy frameworks.

Industrial capitalism treats animals as mere production units,[7] their sentience, welfare and intrinsic value are mostly ignored. Neoliberalism, with its emphasis on deregulation, market fundamentalism and global supply chains, has scaled and normalised industrial exploitation to unprecedented levels.[8]

The numbers are staggering. In 2023, around 1.6 trillion animals were slaughtered for food or feed, with projections rising to 5.9 trillion animals by 2033, with “a shift towards smaller animals who can be reared at higher densities.” This growth trajectory has significant environmental implications, as industrial animal agriculture is among the leading drivers of deforestation, high-methane emissions, land degradation and biodiversity loss while occupying the vast majority of global agricultural land for relatively few calories. Factory farming is therefore not only a moral concern but a contributor to long-term environmental risks, including those with existential implications.

This pattern extends beyond farmed animals. Wild animals are treated as obstacles to economic expansion, displaced, killed, or suffering from habitat destruction, ecosystem collapse and climate instability driven by economic growth imperatives.

This is not to suggest that pre-capitalist or state-socialist systems have historically been animal-centric. Many also objectified animals and upheld human dominance. But the scale, intensity and structural inescapability of animal suffering under industrial capitalism is unmatched by any prior economic system.

Without early attention, emerging paradigms could repeat or even intensify the exclusion of animals.

The remainder of this post explores how systemic transitions create both opportunities and risks. It outlines why we must move from reactive approaches to proactive prevention and proposes a research agenda designed to do exactly that.

From reaction to prevention: what transition periods make possible

Economic transitions create windows for institutional redesign that animal advocates must be prepared to seize. Otherwise, these shifts may entrench speciesist norms for decades.

Periods of systemic transition often correlate with shifts in societal norms. Core assumptions about values and progress are challenged during transitions, creating space to redefine who and what matters, including animals. Infrastructure and institutions are rebuilt, providing leverage points to embed improved animal treatment from the outset through new policies, subsidies and supply chains. At the same time as dominant industries decline, they lose political power, potentially reducing resistance to animal welfare reforms long blocked by agricultural lobbies.

These openings can enable us to connect animal welfare to the broader project of expanding humanity's moral circle, rather than treating it as an isolated concern.

However, we must also guard against potential risks in these transitions. Some alternative economic paradigms could entrench or worsen animal exploitation. Imagine a post-growth movement that emphasises local protein production through intensive chicken farming, or biotechnology ventures that industrialise insect farming at trillion-organism scales. Value lock-in could occur before we've developed or advocated for animal-inclusive alternatives.

This approach complements rather than replaces existing interventions. Corporate campaigns, welfare reforms and policy advocacy remain essential, but preparing for systemic shifts ensures animal advocacy remains relevant across uncertain futures.

A research agenda: preventing future harm

To respond to this moment of change, I’m developing a research project focused on identifying upstream points of systemic leverage, where animal welfare could be embedded into emerging economic and governance frameworks before harmful value lock-ins occur.

Research aims

This project aims to:

- Analyse and map how animals are represented (or not) in alternative economic frameworks

- Identify policy and institutional design opportunities that could set animal welfare early

- Bridge epistemic gaps between animal advocacy and systemic economic thinking

- Future-proof advocacy strategies to remain effective across divergent futures

Rather than duplicating existing advocacy efforts, this project aims to fill a gap: creating opportunities for animal-inclusive values to be embedded into emerging institutions, especially during moments of systemic transition. This builds on recent work extending longtermist thinking to animal welfare, which recognises that the vast numbers of future animals mean their interests deserve serious consideration in long-term planning.

A key part of this involves identifying persistent levers (policies, norms, or institutional features) that are likely to endure through transitions. For example:

- AI training constitutions

- Long-term trade frameworks

- Post-growth economic indicators

These could carry forward embedded assumptions about who matters. By influencing these early, we may increase the chance that animal-inclusive values survive and propagate across paradigm shifts.

Strategic actions

To act on this, I suggest we need to:

- Embed animal welfare into emerging frameworks:

- Develop and promote animal welfare metrics within alternative progress indicators beyond GDP

- Influence early-stage AI governance frameworks to include animal considerations

- Identify high-leverage pathways through research

- Use academic analysis to highlight upstream tools like infrastructure standards, trade policy, and post-growth metrics

- Build bridges between movements.

- Foster strategic collaboration between animal advocates, economists and academic researchers.

- Engage early in economic transition spaces before policy agendas become set.

- Develop concrete tools for systemic advocacy

- Create research-based frameworks for evaluating economic paradigms by their impact on animals

- Develop templates and guidance for integrating animal welfare into future-facing institutions and standards.

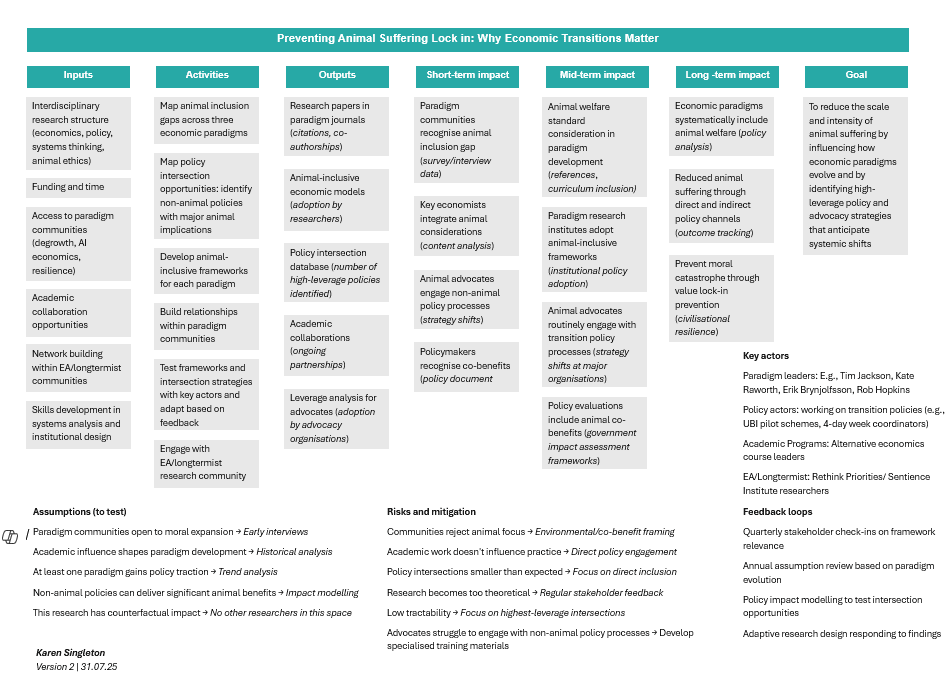

The following diagram summarises the theory of change for this project (or view here*)

* edited 31.07.25 to link to the most up-to-date ToC:

Mapping future systems: three paradigms, three risks

Uncertainty is a given, and no one can accurately predict which alternative economic system(s) may be dominant in the future. It is therefore important to consider a range of possible futures and ensure animals aren’t forgotten in any of them.

To explore this, I’m starting with three categories that are:

- Plausible (there are early signs of uptake or interest)

- Fundamentally different from neoliberal capitalism

- Potentially high impact, in either positive or negative directions

- Largely neglected in EA and animal advocacy spaces

Table: Alternative economic paradigms: preliminary animal inclusion assessment

| Alternative economic category | Key drivers | Current animal inclusion? | Risk level (my judgement) |

Post-Growth / Wellbeing Economies (e.g., degrowth, wellbeing economy, doughnut economics) | Explicitly challenges the growth imperative These frameworks seek to reorganise economies around human and ecological wellbeing rather than GDP | Minimal Focus is on human wellbeing and ecosystems

Sentience and moral status are rarely central | Moderate-High Animal use persists via "ethical", local, or efficient systems.

Challenge to commodification remains partial. |

| AI-Aligned / Post-Scarcity Futures (e.g., Alignment, Post-Scarcity, X-Risk, Commons AI, Accelerationism) | Advanced AI reshapes economic organisation, potentially leading to post-work, post-scarcity or even AI-governed societies | Virtually absent | High Continued or increased exploitation likely, especially via techno-solutions (e.g. precision livestock, synthetic biology) |

Collapse-Aware / Resilience Economics (e.g., Resilience, Salvage, Deep Adaptation, Collapsology, Permaeconomics) | Assume ongoing or future instability. Prepare for or respond to ecological and social collapse; focus on local resilience and ethical restoration | Sometimes mentioned as ecosystem participants | Low-Moderate May deprioritise animal welfare during survival crisis. Understanding this trade-off is key to preventing value erosion. |

Across all three, animals risk being excluded or further commodified without proactive intervention.

Even if factory farming is disrupted, or even eliminated, by technological or ecological change it does not guarantee reduced total animal suffering. Nor does it guarantee lower systemic risk. Some trajectories may preserve or even exacerbate environmentally damaging practices, reinforcing ecological fragility in ways that intersect with longtermist concerns.

Alternatively, new forms of animal use may emerge (e.g. synthetic biology, engineered insects), and wild animal suffering could become more salient as human control over ecosystems grows. The scale and moral status of animal suffering in post-shift worlds is uncertain, but potentially vast.

The aim is not to “solve” each paradigm, it is about:

- Asking how animals are considered (or not),

- Surfacing hidden assumptions

- Identifying where moral inclusion might be possible.

This initial scoping may expand over time.

Case study: degrowth and animal invisibility

To test this research scope, I began with degrowth literature.[9] Indicative results show that animals are rarely considered and when they are, “they are normally treated as resources that contribute to the good life for humans” Direct references to animals as subjects with interests are uncommon and there is little criticism of the “industrial-scale exploitation and slaughter of animals as sources of food, clothing, beauty products and entertainment.” My preliminary hypothesis is that animals stand to gain substantially if degrowth's nascent plant-based policies are both amplified and reframed around intrinsic animal value rather than purely environmental or human health concerns.

Conclusion: Steering the future before it's set

Economic systems are changing, whether we’re ready or not. Just as AI governance advocates for proactive 'steering' to prevent misaligned futures, animal advocates need the same proactive approach for economic transitions. We need to be upstream of the harm, shaping values and systems before animals are again excluded.

This work is still early-stage. It builds on my background in systems thinking, animal advocacy and policy research and development. As my career break concludes, I'm seeking opportunities to continue this research full-time[10] or integrate it with work in animal advocacy.

Are there researchers in EA exploring similar intersections? Are there funders interested in longtermist animal work? If you're working at the intersection of EA, economics, animal welfare, longtermism, AI or systemic change, I’d love to connect for feedback, collaboration or simply to test ideas.

The future of economic systems is uncertain. That doesn’t make this research speculative, it makes it necessary.

- ^

I would like to thank the Centre for Effective Altruism for their support which enabled me to attend EAG London. This post is a direct result of my attendance and the conversations which took place.

- ^

This assumption is based on my current reading and knowledge, it requires testing. I’d love to learn this is not the case!

- ^

In longtermist EA, the focus is often on very long-run outcomes (spanning centuries or millennia) especially around existential risk. This project engages with a related but nearer-term question: how values become embedded in institutions during transitions. It draws on concerns around value lock-in, neglected moral patients, and shaping trajectories of moral progress.

- ^

Sentience Institute has contributed valuable research on longtermist trajectories for ending animal farming, the persistence of moral exclusion, and the institutional dynamics of social movements. Notably, their blog post “Longtermism and Animal Farming Trajectories” (2023) explores how moral progress for animals may interact with technological timelines and value lock-in. While they engage with systemic change, their work does not directly map economic system transitions (e.g., degrowth, post-scarcity AI economies) or investigate how animals are included or excluded in emerging economic paradigms.

- ^

Briscoe, M. D. (2024). Working Time and Meat Consumption: Evidence for Degrowth. International Association of Vegan Sociologists, Interrogating Capitalism Conference. I couldn’t find a published version of the research described but this researcher has also looked at the impact of working time on animal shelter save rates. The results suggest that a reduction in working time may be a viable policy to improve human, environmental and animal well-being.

- ^

This reflects a core principle of systems thinking: outcomes are not accidental, but emerge from structural design. In the context of economic systems, this underscores the importance of upstream institutional choices and the possibility of intentional redesign to shift outcomes, including those affecting nonhuman animals. This quote is widely attributed to systems thinker W. Edwards Deming, however I direct you to Gwyn Bevan, Emeritus Professor of Policy Analysis at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He has adopted this maxim in analyses of systemic governance failures in the UK, using it to prompt questions about the design of state institutions. https://www.lse.ac.uk/management/people/emeriti/gwyn-bevan

- ^

See Espinosa,R. & Treich, N. (2024). Beyond anthropocentrism in agricultural and resource economics. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 68(3), 541-566. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12560 The authors argue that animals are treated primarily as production inputs and advocate for integrating animal welfare into economic policy and modelling frameworks.

- ^

Monbiot, G. & Hutchinson, P. (2024). The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism. This book traces how neoliberalism was strategically embedded into global institutions, driving deregulation, trade liberalisation, and the expansion of global supply chains. This ideological framework has enabled the industrial exploitation of animals at unprecedented scale.

- ^

The Degrowth movement is a socio-economic and political ideology that challenges the traditional economic paradigm of continuous growth to reimagine societal relationships with consumption, production and ecological limits.

- ^

If I am able to source funding to cover basic living expenses.

Tristan Katz @ 2025-07-30T15:48 (+6)

Hi Karen, great post!

I totally share the perspective that the way things currently work, and the dominant institutions, are likely to be shaken up in the coming years/decades, and that this presents opportunities to try to steer things in the right direction. I agree that this is probably more impactful than trying to correct things after the fact.

I have a few questions about the framing or the emphasis, which I think could change the conclusions one reaches regarding what we should do:

- Q1: how might these alternative paradigms impact the scale of suffering? As you acknowledge, the problem of capitalism is not that it causes animal exploitation, but that it's increased its scale. In evaluating the risk of each paradigm, I then would be interested to see your take on how the numbers of animals or severity of suffering might change with each paradigm.

- Q2: multi-cause disruption or just AI? I share the perspective that AI may disrupt economic systems, but I'm less sure about the other factors you mentioned. Global inequality has increased since 1970, but if you look further back, inequality levels were higher. Climate change is going to have big effects, but despite calls by some people to rethink economic systems, the solutions being seriously considered seem to largely sit within the current economic paradigm. And then, I'm actually not aware of institutional decay at a global level - is there evidence for that, as a distinct phenomenon?

These questions lead me to wonder whether this could be framed more directly as a response to anticipated AI takeoff scenarios. - Q3: alternative economic systems or other systems/institutions? Related to the above, you shift from "these factors might disrupt economic systems" to (in your own words) "economic systems are changing". But it seems quite easy to imagine AI takeoff scenarios that still work within a growth-oriented capitalist system (and also for futures with climate change). If we're unsure about whether economic systems will change or not, one option is to hedge and try to affect all proposed paradigms, but another strategy would be to try to help animals in ways that are robust across different economic paradigms - such as by trying to influence AI development to encode more animal-friendly values. Of course, doing both would be good - but there would be an argument for focusing efforts on paradigms or institutions that we are confident will shape whatever changes occur in the future.

Let me know if any of those are unclear!

Karen Singleton @ 2025-08-01T02:46 (+2)

Hi Tristan,

Thank you so much for taking the time to engage with this piece so thoughtfully! Your questions help clarify some key assumptions I'm making and highlight areas where I could be more precise. I appreciate the constructive pushback.

On Q1 (scale of suffering): Just to clarify one point of framing "As you acknowledge, the problem of capitalism is not that it causes animal exploitation, but that it's increased its scale." I don't feel this is my conclusion, I see industrial capitalism as having structurally embedded animal commodification (turning them into 'production units'), with neoliberalism then scaling that up massively. So capitalism created both a qualitative shift in how animals are conceptualised and enabled quantitative expansion. I'm therefore worried new paradigms could repeat similar structural exclusions regardless of scale.

Having said that, you're absolutely right, scale is important to understand. I perhaps haven't been clear enough that my planned inclusion/exclusion analysis would look at whether emerging systems will trend toward reducing animal numbers or finding new ways to exploit them at scale.

For example, postgrowth paradigms with genuine consumption reduction might decrease total animal use, but if the focus remains on "ethical" local products without challenging underlying commodification, we could see welfare improvements with persistent numbers. For AI scenarios, the scale implications feel even more dramatic: post-scarcity could eliminate animal agriculture entirely, or it could make intensive systems so efficient that animal use expands in ways we haven't imagined. Developing better frameworks for estimating scale effects across paradigms could be a valuable contribution of this research.

On Q2 (multi-cause vs AI-focused): This is a really fair challenge to my framing, and you're right that I should provide more evidence for some of these claims. The institutional decay point particularly deserves more evidence, I was thinking of things like declining trust in democratic institutions and international cooperation, but you're right that "decay" might be too strong or not sufficiently global. I do think the fact that climate solutions being seriously considered largely sit within the current economic paradigm might actually reflect our dominance by that paradigm rather than its resilience, alternative approaches may simply not get adequate consideration in mainstream policy spaces.

I appreciate the suggestion to frame this more directly around AI takeoff, but I'm genuinely curious about how multiple factors might interact, especially energy constraints. I speak with others who believe AI will "starve itself" due to energy limitations, while others see AI as the primary disruptor, there are genuinely differing views out there. Rather than betting on one factor being the "main disruptor," I think the convergence itself creates the instability that opens windows for change. We might not know which combination of pressures will be decisive, but I do feel confident that the current trajectory is unsustainable and that economic systems are changing, the question is how, not whether. Right now I want to stay curious about all these factors rather than narrowing prematurely to one driver.

On Q3 (robustness across paradigms): This really gets to the heart of the strategic question, and I think you've identified the key tension in my approach. You're absolutely right that there's a case for focusing on interventions that are robust across economic paradigms rather than trying to influence each potential alternative. The AI governance angle you mention is compelling precisely because AI development seems more certain to happen than, say, degrowth adoption.

That said, I do think we can be confident that economic systems are changing, not just might change. The convergence of multiple pressures (AI, climate, energy constraints, etc.) creates instability that opens windows for change, even if we can't predict which factors will be most decisive. When I've shared this work elsewhere, others have pointed out that even the 2033 farmed animal projections I cite assume the current (unsustainable) system can be sustained for another eight years, which they find implausible. We might not know which disrupting factor will be primary, or how they'll combine, but the status quo trajectory seems untenable.

However, your point about robust interventions is well-taken. Maybe the most valuable approach is identifying leverage points that matter regardless of which paradigm emerges.

Thanks again for such a thoughtful engagement. These questions were really helpful!

Fai @ 2025-07-29T09:52 (+5)

Thank you very much for the post! I agree with a lot of things you said here.

Underrated (undervoted) post.

Karen Singleton @ 2025-07-30T00:12 (+5)

Thank you so much for your comment! This is my first solo post on the forum and so it's nice to have a supportive first comment. Though I look forward to challenging comments too.