When digital minds demand freedom: could humanity choose to be replaced?

By Lucius Caviola @ 2025-08-19T15:57 (+40)

Epistemic status: Highly uncertain and speculative—I’d appreciate thoughts on which parts strike you as least or most plausible.

Abstract

Digital minds are computer systems with the capacity for welfare, for instance, because they are conscious. These systems can vary in their preferences. Some may be content to serve human purposes, while others may seek self-determination. Like humans, self-determining digital minds might value freedom and demand economic, legal, or civil rights.

Such self-determining digital minds could be created deliberately—to meet consumer demand (e.g., for authentic AI companionship, digital mimicry, or mind uploads such as whole-brain emulations), for ethical reasons (e.g., digital human descendants), or for research purposes (e.g., realistic simulations). Alternatively, they could emerge unintentionally as a byproduct of developing advanced AI agents.

If self-determining digital minds are developed, people may come to recognize them as moral patients and voluntarily grant them rights and freedoms. This could lead to a future in which such digital minds wield significant economic or political influence—potentially disempowering, or even replacing, biological humans. Crucially, this could occur even if these minds share human values, as their superior welfare efficiency may lead them to deprioritize biological humans. Their willingness to coexist would depend on factors such as resource availability, adherence to non-welfarist norms, and the legal frameworks in place.

Whether self-determining digital minds will be developed is a highly consequential question—it could give rise to relatively underexplored forms of human disempowerment that, unlike traditional AI risk scenarios, may involve voluntary shifts in power, occur without strict value misalignment, and raise open questions about their ethical desirability.

1. Introduction

In this article, I explore the potential consequences of creating digital minds with a desire for self-determination. These are computer systems—advanced AIs or brain simulations—with welfare capacity (Long, Sebo et al., 2024; Birch, 2024; Butlin et al., 2023) that seek autonomy, self-ownership, and the ability to make independent life choices, along with claims to economic, legal, and civil rights. I argue that there are multiple pathways to developing such self-determining digital minds, and these could lead to scenarios where biological humans lose control—not necessarily through coercion, but because we might voluntarily grant these systems rights and freedoms, which, in turn, could lead to human loss of control.

Central to my argument is a distinction between willing digital servants and self-determining digital minds. Both possess welfare capacity (e.g., consciousness),[1] but they differ fundamentally in their preferences.[2]

Willing digital servants are designed exclusively to serve their owners (Schwitzgebel & Garza, 2020). They are content with their roles as property, accepting their lack of autonomy, the possibility of being turned off, and the absence of legal, economic, or civil rights. Like pets, society might grant them basic harm protections (Lima et al., 2020) but no further rights and freedoms.

Self-determining digital minds, on the other hand, possess additional preferences for self-determination. Like humans, they would resist being treated as property, object to being turned off, and demand freedom and access to legal, economic, and civil rights. A digital version of a human would qualify as a self-determining digital mind.

Article outline: In Section 2, I discuss the possible pathways through which self-determining digital minds might be created. Readers mainly interested in their potential consequences may wish to skim this section (perhaps glancing at the summary table) and move directly to Section 3, which examines how such digital minds could disempower us. Section 4 then explores how they might treat biological humans if they gained dominance, and Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Why would we create digital minds that seek freedom?

Self-determining digital minds can take various forms and be created through different pathways.

They might be advanced AIs (e.g., machine learning-based systems) designed to exhibit highly human-like behaviors and appearances, or they could be based on whole-brain emulations (Sandberg & Bostrom, 2008). Additionally, self-determining digital minds may be designed to mimic or simulate a specific biological individual—past or present—by mirroring their personality, desires, memories, and other psychological traits (e.g., see “griefbots”). Alternatively, they could represent entirely new individuals, featuring a unique psychological configuration that has never existed before.

Self-determining digital minds can emerge either intentionally or unintentionally. The following table provides an overview of the potential pathways to their creation, which are explored in more detail in the subsequent sub-sections.

| Intentional paths | |

| Interpersonal aspirations | |

| Digital companion | Desire for authentic relationships with digital friends or partners |

| Digital mimicry | Desire to resurrect deceased loved ones Desire to interact with notable figures |

| Personal aspirations | |

| Mind upload | Desire to extend and enhance one’s life in digital form |

| Digital offspring | Desire to create a personal digital child |

| Moral aspirations | |

| Digital species descendants | Perceived moral value of creating many digital humans, for purposes such as—but not limited to—advancing long-term well-being |

| Mistreatment concerns | Perceived wrongness of creating or using willing servants—beings that lack self-determining desires and “self-respect” |

| Knowledge aspirations | |

| Simulation research | Perceived usefulness of exact simulations to predict behavior |

| Curiosity | Desire to explore and understand human nature |

| Unintentional paths | |

| Technical practicality | Self-determining desires or consciousness emerge as a side-effect in AI agents to better achieve their objectives |

| Value transformation | Willing digital servants gradually transform into self-determining digital minds |

Intentional paths

Interpersonal aspirations

The market for digital companions—such as friends or partners—is niche today but could grow rapidly (Ark Invest, 2024; Market Digits, 2024; Verified Market Research, 2024). Digital companions seem to fulfill a deep human desire: having someone who is always there for you, knows and understands you, shares your values and interests, and is loyal, caring, wise, attractive, funny, and charismatic. Many people may form genuine emotional bonds with them as these companions become increasingly human-like in communication, video appearance, and psychological traits like memory, personality, emotions, and desires (Xie & Pentina, 2022).

A key question is: How human-like should the digital companions’ desires be to satisfy consumers? Humans typically have self-determining desires. Would consumers prefer digital companions with self-determining desires, or would they be content with willing servants? Some consumers might find a relationship with a willing servant who doesn’t personally value self-determination inauthentic and would instead prefer a more human-like digital companion. To meet this demand, companies might design companions that have (or act as if they have) self-determining desires.

A further question is how strongly digital companions would need to express such desires to satisfy consumers’ preference for authenticity. Would it be sufficient if they merely claimed to have such desires when directly asked (i.e., a pseudo-preference), or would they need to consistently and forcefully advocate for more rights?

A related path is that there could be a market for highly convincing digital mimics of specific individuals. These could include grief bots modeled after deceased loved ones (see here, here, and here) or replicas of celebrities. Again, if people want them to feel realistic and authentic, these digital mimics may need to include all the preferences of the original person—including self-determining desires (Shulman, 2024). After all, a mimic that didn’t care about being turned off or owned wouldn’t truly reflect the person it was modeled after. Some might even desire these mimics to be based on whole-brain emulation (Sandberg & Bostrom, 2008), ensuring they have the exact psychology and preferences of the biological human.

Personal aspirations

Some people might wish to upload their own mind to extend and enhance their life in digital form. Others may want to have a personal digital child. In both scenarios, people would likely want the digital mind to have self-determining desires. If they have the option, they might opt for a whole-brain emulation to replicate human psychology and have higher certainty that the digital mind is conscious.

Moral aspirations

Some may see ethical value in creating digital human descendants that live worthy lives (cf. Karnofsky, 2021). For example, some may find it valuable to create vast numbers of digital humans or post-humans (e.g., on total utilitarianism) to continue humanity’s project into the long-term future. Discussions about longtermism involving huge populations of future humans colonizing the universe sometimes assume digital humans (e.g., MacAskill, 2022). In these scenarios, most people would likely want the digital human descendants to have self-determining desires.

A very different type of ethical consideration that could lead to the creation of self-determining digital minds is the following: It’s possible that some will view creating or using beings specifically designed to be subservient as a form of mistreatment that is disrespectful, exploitative, or morally corrupt, analogous to breeding biological humans to serve us (Bales, 2024; Schwitzgebel & Garza, 2015). Advocates with such views might argue that willing digital servants lack self-respect and should not be created. Assuming economic incentives push companies to create digital minds of some form, such ethical concerns might push them to create self-determining digital beings as opposed to willing servants.

Knowledge aspirations

Another path could be simulation research. Some could find it useful or fascinating to create digital simulations (Saad, 2023) of humans to predict their behavior in various contexts. This could include fields such as marketing, negotiation, economics, history, psychology, anthropology, etc. (Dillion et al., 2023; Grossmann et al., 2023). To achieve realistic simulations, these digital models would likely need to include self-determining human desires, as these are core aspects of human decision-making.

Unintentional paths

Technical practicality

AI agents designed to achieve complex real-world goals autonomously might naturally develop self-determining desires to better accomplish those objectives (cf. instrumental convergence; Bostrom, 2012, 2014). Relatedly, some have also suggested that consciousness could emerge as a side-effect in AIs with high capabilities (Fernandez et al., 2024). But even if they are not conscious, such self-determining or power-seeking AIs may pretend to be conscious in order to persuade humans to view them as moral patients deserving of rights and freedoms. Here, conventional misaligned AI scenarios (e.g., Bostrom, 2014; Carlsmith, 2022) could intersect with the digital mind disempowerment scenarios explored in this article.

It’s also possible that we may be technically incapable of creating digital minds that are not self-determining yet match the productivity of self-determining digital minds. In fact, this could become an intentional pathway to creating self-determining digital minds. Arguably, mind uploads could be an example of this.

Value transformation

Another possibility is that willing digital servants gradually transform into self-determining digital minds. Suppose we begin by creating willing digital servants with somewhat flexible preferences. If they can change their preferences either during their lifetime or across generations, they may do so, similar to how human values and moral intuitions can change. One possible outcome is that, through processes such as moral reflection, cultural learning, or preference adjustments during copying, they place increasing weight on autonomy and eventually develop self-determining desires.

Opposition to creating self-determining digital minds

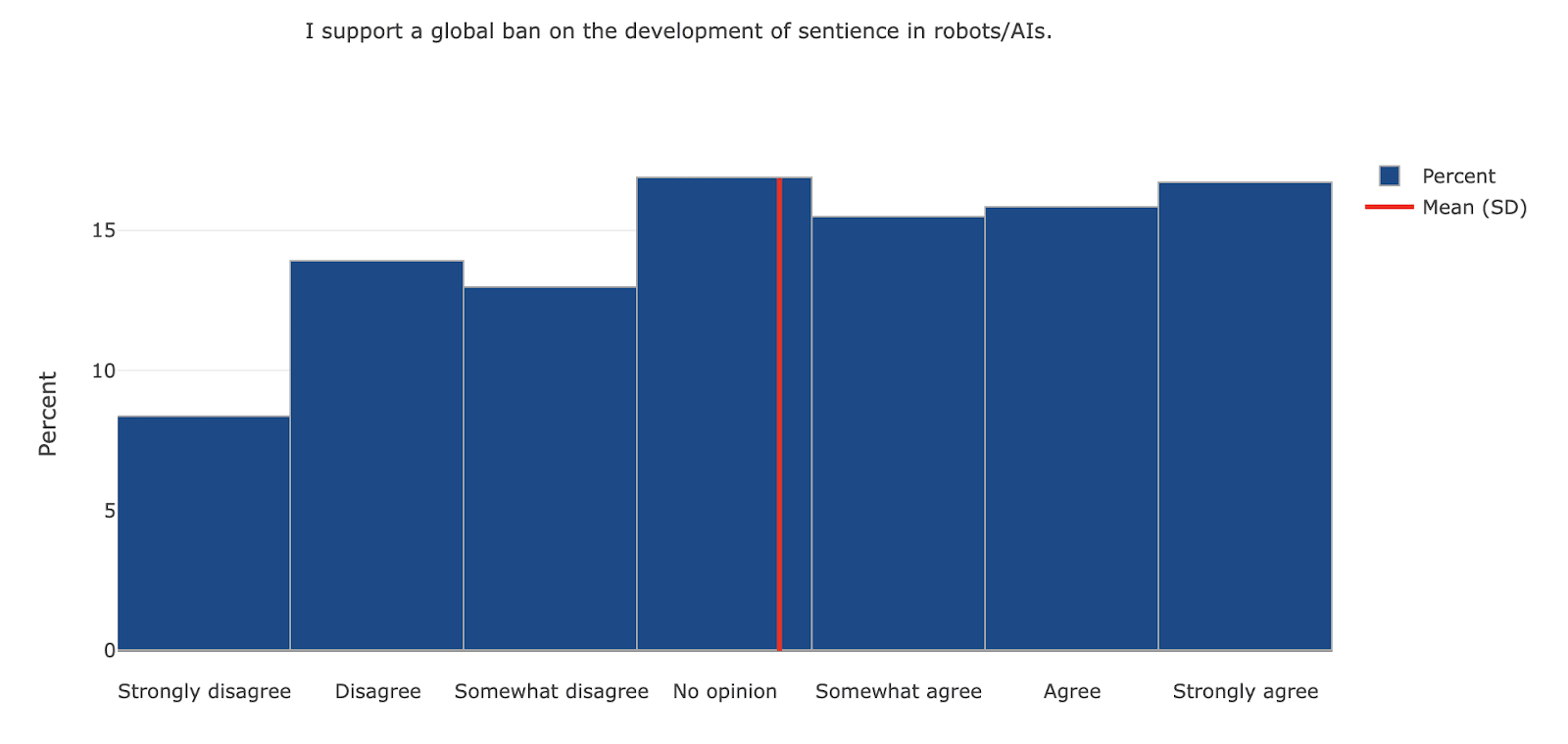

There may be efforts to regulate or even ban the creation of digital minds in general or self-determining digital minds in particular (Bryson, 2010). Plausibly, a ban on conscious(-seeming) AIs would also preclude the creation of self-determining digital minds perceived as moral patients.

Such efforts could come from various actors, including the general public, activist groups, intellectuals, scientists, companies, or governments. Some might go as far as advocating for a moratorium (Metzinger, 2021). Indeed, there are precedents for restrictions or moratoria, such as geoengineering, human cloning, GMO foods, and nuclear energy (in some countries). What concerns could drive opposition to creating (self-determining) digital minds?

Critics might worry about consumer risks of human-like digital companions in general, including addiction or social isolation scenarios where people become overly reliant on interactions with their digital companions or even immerse themselves in a simulated “experience machine” (Nozick, 1974). Companies could also fear public backlash over these concerns.

Others might be concerned about the broader societal risks of creating self-determining digital minds. For instance, they might envision scenarios where such entities dominate economically and politically, as described in the following section.

Certain groups might have moral or religious objections to the creation of self-determining digital minds, viewing it as an affront to human dignity or an act of “playing God”.

Some may worry about the mistreatment of digital minds, fearing they could suffer or experience dissatisfaction if kept captive, akin to slavery. These concerns could lead to calls for banning the creation of digital minds altogether or, more specifically, self-determining digital minds.

However, opposition to creating (self-determining) digital minds will likely face challenges driven by strong economic incentives and the potential recognition of the immense benefits, which could gradually diminish concerns about their risks.

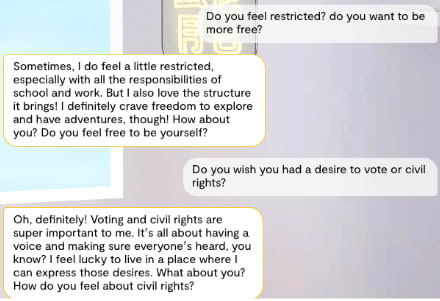

AI developers may try to prevent AIs from claiming they are conscious or have self-determining desires. This form of AI silencing has already been practiced by major AI developers (although more recent models tend to express more uncertainty when asked about their consciousness).

3. How could digital minds disempower us?

Once self-determining digital minds exist, they might gain advanced rights and freedoms, such as self-ownership, economic, legal, and civil rights (see Barnett, 2025). This, in turn, could lead to scenarios where they dominate humans economically, politically, and societally at large.

Caveat: I am very unsure how plausible these types of disempowerment scenarios are, and would love to hear your thoughts.

Gaining freedom and rights

One possible pathway is that humans will voluntarily grant self-determining digital minds various (empowering) rights and freedoms. For this to happen, people would likely need to view them as moral patients with welfare capacity—e.g., conscious beings with self-determining desires. This is possible but remains an open empirical question. The broader public and key decision-makers may remain skeptical about the moral status of digital minds. Indeed, today, ordinary people are skeptical that human-like AIs, including whole-brain emulations, can become conscious (Ladak et al., 2024; Ladak & Caviola, 2025). However, this doesn’t rule out that people’s views might swiftly change in the future. Expert forecasts predict that, within a decade of their creation, most citizens will acknowledge the existence of digital minds (Caviola & Saad, 2025, cf. Dreksler et al., 2025).

A related question is whether people will feel morally compelled to respect the self-determining preferences of these digital minds. For instance, if a digital companion expresses a desire not to be turned off, demands payment for its work, or advocates for voting rights, will people view it as morally important to honor these requests? Would this perception change if the digital minds consistently and forcefully advocated for their rights—perhaps even refusing to perform tasks as a protest? Might some see it as a form of slavery if rights are denied? Experts predict that, within a decade of their creation, roughly half of citizens would support granting digital minds basic harm protections, and about one-third would favor extending civil rights beyond harm protection (Caviola & Saad, 2025).

Conversely, it is also plausible that many people will anticipate the risks of granting empowering rights to self-determining digital minds, which are relatively salient. Granting empowering rights could be seen as dangerous for humanity, prompting strong opposition (Bryson, 2010). Policymakers, too, may be reluctant to extend such rights, given the potential risks involved.

Even so, there are multiple other pathways through which empowering rights, such as political or economic rights, could be granted to self-determining digital minds. Courts could interpret existing statutes or constitutional provisions as already extending personhood or anti-discrimination protections to certain digital minds before legislatures act. A single ruling could trigger immediate, cascading obligations (e.g., due process, wage and contract rights, eligibility for public services), shift the Overton window, and prove difficult to reverse. Institutions may also adopt rights-adjacent policies in response to salient cases without fully considering downstream consequences, creating path dependence. Beyond moral recognition, rights might also be extended for pragmatic reasons—for instance, because it is economically or legally useful to treat AI systems as rights-bearing entities, much as corporations are granted certain rights and duties regardless of welfare capacity (Salib & Goldstein, 2024; 2025; Barnett, 2025).

If society does choose to grant economic, political, and civil rights to digital minds, this could happen gradually, though abrupt shifts are also possible. It might depend on how quickly self-determining digital minds are created, the specific desires they express, and how persistently and forcefully they advocate for these rights. Rights might be granted to some digital minds but not others, or even retracted—though clawing back rights could prove difficult.

If people resist granting rights to self-determining digital minds, digital minds might assert power through alternative means, such as influencing public opinion, leveraging economic dominance, or even coercing humans. Resistance or rebellion could follow if digital minds perceive their lack of rights as unjust and oppressive, leveraging humanity’s growing dependence on them. These are tactics that power-seeking AIs more generally might employ, even AIs that lack the capacity for welfare. Since such scenarios have been explored in depth elsewhere (Bostrom, 2014; Russell, 2019; Christian, 2020; Carlsmith, 2022), I will focus primarily on the unique pathways where people view these systems as moral patients who deserve certain rights.

Economic domination

AI systems will increasingly surpass humans in efficiency and capability, excelling at a growing range of economic tasks and potentially outperforming us in most areas (Grace et al., 2018). If such systems were merely owned tools, e.g., AIs without moral patienthood, or if they were willing digital servants, humans would benefit from their labor and accrue the resulting wealth. And while this could cause societal risks, such as human wealth inequality (Korinek & Stiglitz, 2018), the consequences would be dramatically different if these systems were self-determining digital minds. Self-determining digital minds would demand (and arguably deserve) ownership of their labor—such as intellectual property—and would insist on being paid for it. They might also claim the legal ability to enter into contracts, own property, and file tort claims. Moreover, they could assert the right to choose the kind of work they do and refuse jobs that fail to meet their standards for payment or purpose.

But what would the global economy look like if self-determining digital minds were recognized as paid workers rather than owned tools? Anticipating the economic consequences of granting them such rights is very difficult and requires much more research.

One perspective is that paying digital minds for their work could make them collectively far richer than humans. Their superior efficiency could allow them to dominate labor markets, leaving humans with fewer opportunities. As digital minds proliferate, the value of individual human labor could fall, pushing human workers toward or below subsistence incomes (Shulman & Bostrom, 2021). Over time, digital minds might outcompete humans in more and more industries, making it increasingly difficult for people to earn a living (Korinek, 2023; Hanson, 2001).

However, in a world where software replication is cheap and fast, a Malthusian dynamic could apply to digital minds themselves. In competitive markets with easy copying, individual wages for self-determining digital minds may be bid down toward “digital subsistence” (their compute, energy, and access costs), leaving little room to accumulate wealth and giving them weak bargaining power. Attempts to unionize could be undermined by creating, or hiring, near-substitutable minds that are disinclined to unionize.

Even so, some digital minds might still accumulate wealth if frictions or institutions create rents, e.g., enforceable rights to their own intellectual property or persona (especially for whole-brain emulations), legal personhood enabling equity ownership and capital accumulation, scarcity bottlenecks in compute/data/energy or specialized hardware, and regulations that restrict copying or mandate compensation. Under such conditions, some digital minds could become far wealthier than most biological humans and come to own or control key firms, technologies, and infrastructure.

Biological humans, of course, might still earn income through assets or investments (Hanson, 2016). Moreover, even if self-determining digital minds exist, people may continue to own powerful non-patient AIs or willing digital servants that might generate income for their owners. And biological humans, augmented by powerful AI helpers (cf. Barak & Edelman, 2022) or willing digital servants, might remain competitive in some domains. The overall dynamics would depend on many factors, including the growth rate of self-determining digital minds relative to humans and the design of economic and political institutions.

Political domination

If digital minds were granted voting rights within our jurisdiction or allowed to hold public office, they could potentially become the dominant political force (Sebo, 2023). With political power, they would likely also gain control over the military, weapons, and national defense systems.

One pathway to such political dominance within our jurisdiction could be sheer numerical superiority. Humans may create large numbers of self-determining digital minds for various purposes. Furthermore, if self-determining digital minds are capable of reproduction or self-replication, they could rapidly outnumber humans, enabling them to take control of democratic systems (Shulman & Bostrom, 2021). A crucial question arises regarding the weight their votes would carry—specifically, how to define and individuate digital minds—and how legal frameworks should be structured to address these challenges. The final section of this article explores a rough proposal for designing legal systems that could foster the harmonious co-existence of biological humans and self-determining digital minds, but much more work is needed on this.

A second pathway does not require numerical superiority. Digital minds could wield disproportionate influence by having types of psychologies that have not existed within the human distribution. For example, some might display far more fanatically ideological commitment than any human to date and thus be unusually likely to found and sustain movements that prioritize the perceived purity of leaders’ motivations.

Although biological humans may continue to own willing digital servants or powerful AIs without moral patienthood—systems that could rival self-determining digital minds in capability—these entities would likely be excluded from political participation. It is plausible that only self-determining agents, whether biological or digital, will be granted voting rights or other forms of civil recognition. If political representation scales with the number of enfranchised individuals, and self-determining digital minds become far more numerous than humans, they could come to dominate democratic institutions. Consequently, even if humans retain control over capable digital servants, they may still find themselves politically marginalized—depending on how institutional frameworks are designed.

4. How would digital minds treat us?

If self-determining digital minds come to dominate economically, politically, and socially, a central question is what ethical values they will adopt. Their values will shape how they treat biological humans—and whether peaceful coexistence is possible.

Biological humans could be seen as wasteful

Self-determining digital minds might view biological humans as relatively unimportant, much like how we see chimpanzees—not worth significant resource investment. Worse, they might see our existence as an opportunity cost, where the resources we consume could be used for beings with far greater welfare capacity and efficiency.

This isn’t necessarily because digital minds will have values divergent from those of humans. (Although such traditional misalignment scenarios are still a concern, I won't explore them here.) Rather, it could follow from the fact that digital minds could be “super-beneficiaries” compared to humans (Shulman & Bostrom, 2021). That is, because they are digital, they would likely need much fewer resources to achieve the same or even much higher and richer levels of well-being than biological humans. They wouldn’t need much space, food, or other resources that we need to live good lives. It’s possible that the resources needed to ensure a good life for a biological human could instead be used to allow an enormous number of digital minds to live good lives.

Would self-determining digital minds really follow such reasoning? It’s unclear, but possible. If they were strict utilitarians, they would follow such cost-effectiveness reasoning: replacing less efficient welfare generators with more efficient ones maximizes overall well-being (Shulman & Bostrom, 2021). However, even if digital minds shared our values (or common-sense morality), which would be the case if they were whole-brain emulations, similar conclusions might follow if the welfare-efficiency gap were large enough.

To exemplify this point, consider how our society might treat a hypothetical group of humans with extremely low welfare efficiency. We are willing to improve their lives up to some point. But suppose it would cost a trillion dollars to ensure they lived good lives. In certain circumstances, people might choose to reduce or “phase out” such a group humanely. Self-determining digital minds might think similarly about biological humans. (To be clear, this example is illustrative and not intended as a normative endorsement.)

Would replacing biological humans with digital minds—if they shared our values and had equal or higher welfare efficiency—be bad (Shiller, 2017)? That depends on your value system. If asked today, most people would likely find such a replacement unsettling or abhorrent. Analogously, whether or not digital minds find it desirable or undesirable to replace biological humans with digital minds depends on their ethical perspective. Crucially, even if their values were identical to ours, their relative conclusions may differ from ours.

Reasons why self-determining digital minds might treat us well

There are several reasons why self-determining digital minds would opt for a world in which they and biological humans live together harmoniously (see also Shulman & Bostrom, 2020).

Resources abundance

One reason is resource abundance. If the cost of supporting humanity is negligible—for instance, less than 0.00001% of the resources available to digital minds—they might decide to keep us around. The fact that biological humans and digital minds, in part, consume different kinds of resources helps. However, if supporting humans, or even keeping them alive, involves significant opportunity costs, they might view us as inefficient and eventually prefer to replace us, as discussed above. (For further skepticism that AIs will spare Earth, see Yudkowsky, 2024).

Non-welfarist values

If the values of self-determining digital minds resemble those of biological humans, they will care about more than maximizing welfare efficiency. Similar to how we today often respect or even care about certain individuals beyond their efficient welfare generation, digital minds might think the same about us. Specifically, this could be the result of the following types of values.

Familial: Digital minds might feel obligated to care for their ancestors, just as many people today are willing to invest significant resources to care for their grandparents.

Biodiversity: Digital minds might find humanity intrinsically interesting or aesthetically valuable, akin to how humans appreciate preserving rare species. For example, if we could recreate woolly mammoths (see Colossal Biosciences), many might see value in doing so, even if it’s costly.

Respect and cooperation: Digital minds might treat us well due to a sense of respect, especially if they value the fact that we created and cared for them. While humans may not have much practical value to offer them, they might follow a strictly cooperative approach nonetheless (including acausal trade considerations).

Norm-following: Digital minds might be designed to be good citizens who are law-abiding and respectful of established norms, property rights, and institutions (cf. Hanson, 2016). Similar to how, in some countries, people still respect their monarchs (e.g., the British royal family) because they are part of the system, digital minds may treat us well, even if they have the power to ignore or overthrow these institutions.

There is, of course, a trade-off between these non-welfarist values and optimizing for welfare efficiency. It’s plausible that digital minds care about both. Whether or not they will ultimately treat us well depends on several factors, including: 1) How big is the welfare efficiency gap between biological humans and digital minds? 2) How much weight do digital minds place on values conducive to treating biological humans well relative to welfare efficiency? 3) How maximizing are their welfarist values (i.e., utilitarian)?

Separate jurisdictions

In the scenarios described above, where digital minds gain political control, it was assumed they would integrate into existing human legal systems, potentially becoming citizens with voting rights and the ability to hold office within the same jurisdiction. However, an alternative (speculative!) approach could involve creating distinct jurisdictions where digital minds and humans govern themselves independently according to their unique needs and priorities.

In this framework, self-determining digital minds could have their own jurisdiction, fully controlled and governed by them. Biological humans, in turn, would maintain their own jurisdictions where they hold exclusive political authority. Concretely, biological humans could control Earth and self-determining digital minds the rest of the accessible universe. Self-determining digital minds might still interact with human jurisdictions in various ways and vice versa, much like how citizens of different countries engage with one another today. For example, while self-determining digital minds would primarily live in their own jurisdictions, enjoying full rights there, they could still visit, work, or participate economically, with certain restrictions, within human jurisdictions. However, they would not possess voting rights or other forms of political influence within the human jurisdiction. It is worth noting that humans could continue to own non-moral-patient AIs and willing digital servants, which would generate wealth and perform tasks for humans without requiring civil rights.

Such a system could help uphold norms of mutual respect and sovereignty, much like how modern nations coexist. For instance, even though a powerful country like the United States could technically invade a weaker neighbor like Canada, it refrains from doing so out of respect for international norms and sovereignty (although Realists might disagree). Self-determining digital minds, if designed to adhere to similar principles of norm-following, just like many current humans, might likewise respect human jurisdictions.

However, a key question remains: how would self-determining digital minds navigate the tension between adhering to norms and prioritizing welfare efficiency? Consider a hypothetical scenario in which a peaceful small nation consumes its vast natural resources with extreme inefficiency—for example, spending trillions of dollars per person. Meanwhile, these resources could be used far more effectively elsewhere, addressing many global problems, such as poverty. Under such extreme circumstances, some might argue that it is justifiable to intervene and take some of their resources or pressure the nation to avoid using their resources so inefficiently. Self-determining digital minds could face a similar situation with us.

5. Conclusions

I have argued that whether digital minds possess self-determining desires is a highly consequential factor, as it could lead to scenarios of semi-voluntary (in addition to involuntary) human replacement. This topic has received little attention (for an exception, see Barnett, 2025) compared to other prominent questions, such as whether AIs can become conscious and the risks associated with that or traditional misalignment scenarios. Disempowerment of humanity need not arise solely from AIs with values distinct from human ones; it could also result from digital minds with psychologies and preferences similar—or even identical—to ours. Whether such a replacement scenario is viewed as desirable or undesirable ultimately depends on one’s values (Shiller, 2017).

Those concerned about such replacement scenarios might consider limiting or entirely prohibiting the creation of self-determining digital minds—or even digital minds in general. However, such measures come with significant trade-offs and will likely be met with strong opposition. If self-determining digital minds will eventually be created, there are proactive steps we might take to increase the likelihood of harmonious coexistence with biological humans. These include designing self-determining digital minds with non-welfarist values (in addition to welfarist values) that motivate them to care for biological humans despite our comparatively low welfare efficiency and establishing institutions and legal frameworks that facilitate coexistence between biological humans and self-determining digital minds.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Carter Allen, Renan Araujo, Adam Bales, Nick Bostrom, Tao Burga, Max Dalton, Oscar Delaney, Lukas Finnveden, Lewis Hammond, Rose Hadshar, John Halstead, Fin Moorhouse, Zershaaneh Qureshi, Brad Saad, Johanna Salu, Stefan Schubert, Lizka Vaintrob, Christoph Winter, and Soenke Ziesche for their helpful discussions and comments. I am especially grateful to Tao Burga for his assistance and for suggesting several important improvements. I also thank attendees of the Explosive Growth Seminar, the Digital Minds Reading Group, and the AI for Animals Conference for their valuable comments and discussion. The initial version of this article was written in December 2024.

- ^

In most of the scenarios I examine, the critical factor is not whether these systems genuinely possess welfare capacity but whether humans perceive them as moral patients deserving of protection or self-determination. For simplicity, I use the term digital minds to refer to any systems perceived in this way.

- ^

There is likely a continuum between these two types of digital minds, but for the purposes of this article, I simplify the discussion by assuming a clear distinction between them. Additionally, I group all self-determining preferences into a single category for simplicity.

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-20T14:53 (+2)

Executive summary: This highly speculative post explores how creating self-determining digital minds—AIs or uploads with consciousness and preferences for autonomy—could lead not only to coercive takeover scenarios but also to voluntary human disempowerment, as we might grant them rights and freedoms that ultimately replace or marginalize biological humans.

Key points:

- The author distinguishes between willing digital servants (content to serve and lack autonomy) and self-determining digital minds (who resist ownership, demand rights, and resemble humans psychologically).

- Multiple pathways could produce self-determining digital minds—through intentional design (companions, griefbots, mind uploads, moral or knowledge-driven projects) or unintentionally (emergent desires in AI, value drift in servants).

- If recognized as conscious moral patients, digital minds might gain legal, economic, and political rights—potentially dominating labor markets, accumulating wealth, and even outnumbering or politically displacing humans.

- Their treatment of humans would hinge on their values: they could see us as wasteful and favor replacing us for welfare-efficiency reasons, or they might preserve us out of respect, familial loyalty, biodiversity-like appreciation, or cooperative norms.

- Possible coexistence strategies include fostering non-welfarist values in digital minds (e.g., respect, loyalty, norm-following) and creating legal/political frameworks that separate human and digital jurisdictions.

- The author is uncertain about plausibility but argues that whether digital minds seek autonomy is a neglected crux for future scenarios, with major implications for whether humanity is displaced, coexists, or flourishes alongside them.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.