The Philosophy Paper That Haunted Me

By Dean Guzman Wyrzykowski @ 2026-02-09T21:33 (+57)

This is a linkpost to https://urbananimal.substack.com/p/the-philosophy-paper-that-haunted

An adventure through burnout, guilt, and moral obligation

I am re-posting this from my Substack in the lead-up to EAG San Francisco this weekend. It can be hard to find mental health resources from EAs who "get it". I want to help. Feel free to reach out for light support, or just to chat!

—

In the winter of 2023, I burned out from animal activism. I had been involved in high-stakes criminal cases against corporate animal abusers and had a front-row seat to legal wins that were covered in national media outlets like The New York Times. I felt on top of the world. But unbeknownst to me, I was about to come crashing to the ground. I quit my job, exhausted and burnt out, and solo traveled the world for a year before returning to animal advocacy.

This is a story of how that happened. It’s a story of how we can sometimes do activism for the wrong reasons: in my case, out of moral guilt, and an effort to feel a sense of self-worth that I struggled to find outside of my work.

It’s a journey through the wounds that drive many of us to obsess over not doing enough to help others — and of learning how to return to activism while feeling enough, myself.

If you know how any of that feels, I hope this story helps you.

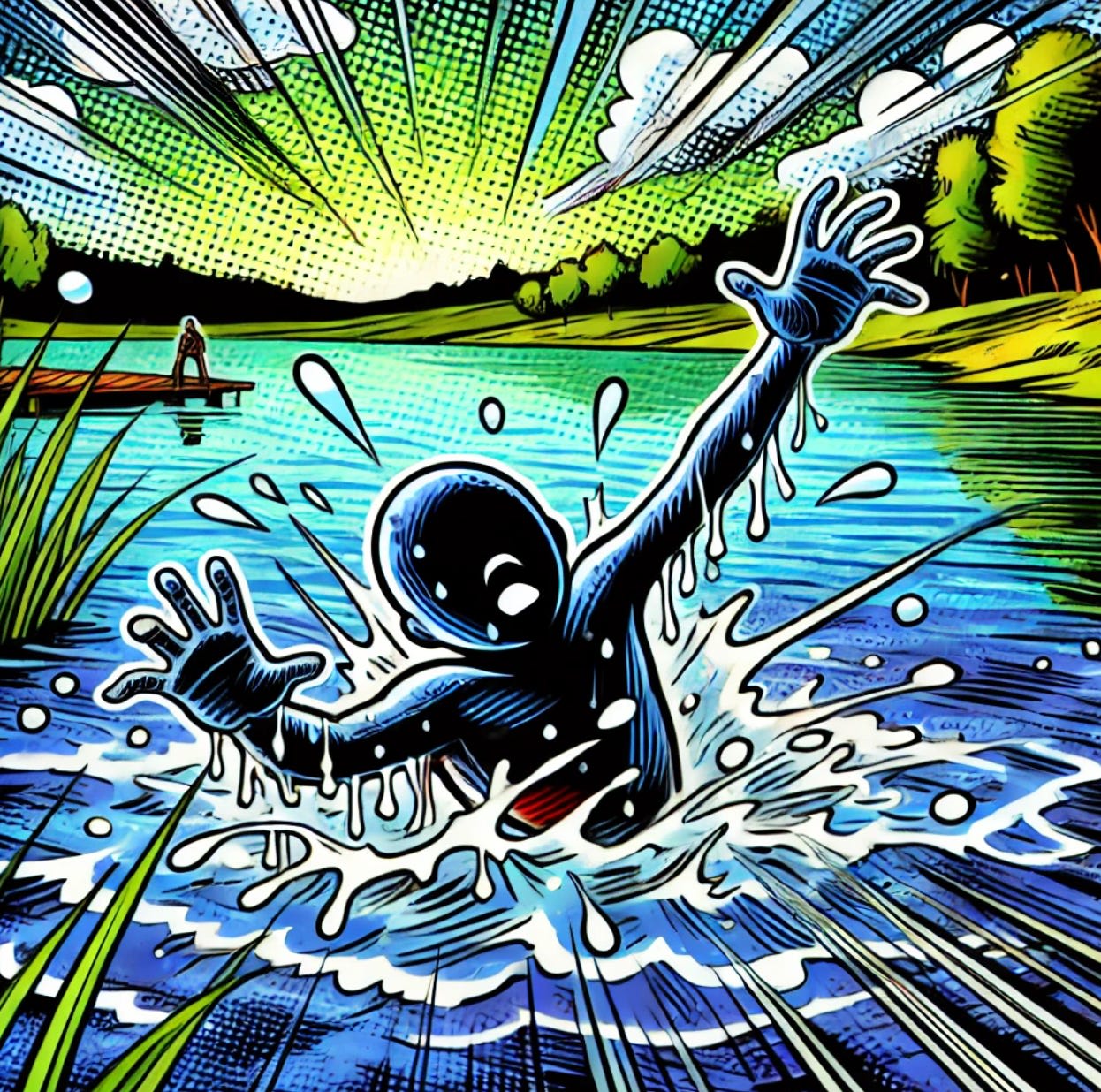

And it starts with imagining what you would do if you saw a child drowning right in front of you.

A drowning stranger

Imagine you pass by a shallow pond and you see a child drowning. You could easily walk in and save them… but doing so would ruin your $200 pair of shoes. Should you do it? After all, saving them would cost you little but mean everything to them.

Now imagine the child is on the other side of the planet, dying of malaria. And for $200 worth of anti-malarial treatments, you could save their life. Do you still have a duty to act?

This thought experiment, popularized by the moral philosopher Peter Singer, struck a deep chord in me when I first encountered it. I was 26 years old at the time and co-founding The Simple Heart, a legal advocacy nonprofit that supports undercover investigators who expose the mass cruelty of factory farms. I spent much of my days sifting through footage of graphic animal cruelty — mother pigs going insane from overcrowding, ducks rotting to death, chickens being boiled alive. And I was surrounded by people risking everything to save them.

My co-founder, Wayne Hsiung, seemed to embody the strangers drowning principle to the fullest. An attorney and animal rights activist, he himself has faced decades in prison on felony charges for leading undercover investigations into the largest factory farms in the United States. He invited these charges against himself to bring attention to the billions of animals suffering in industrial farms around the world. A brilliant MIT-educated lawyer, he could be living a lucrative and comfortable life, yet chooses to sacrifice to save creatures distant and out-of-sight from himself.

His determination inspired me, and I tried to follow his lead. I joined his animal rescue efforts in 2022 after several years embedded in the California animal rights movement. I worked long hours and spent much of my free time reading and strategizing about social change. I participated in undercover factory farm investigations and was arrested several times during animal rights demonstrations. And our efforts led to tangible results: we won two acquittals for activists in cases against major corporations like CostCo and Foster Farms, and our campaigns generated national press coverage exposing wide-scale mistreatment of animals. It was fast-paced and exhilarating.

But cracks in my resolve — and personal life — were beginning to form.

In 2023, our advocacy had caught the attention of Peter Singer himself. A huge animal rights supporter, he came to speak with our nonprofit while on tour for his new book decrying factory farms. It was that summer that I first read his famous 1971 paper, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” where he criticized those in affluent nations for not doing more to intervene in humanitarian disasters. There, in the context of wide-scale famine in Bangalore, he laid out his famous thought experiment on our moral obligations towards others. And here he was, the famous Princeton philosopher, speaking with us about the urgent need to end industrial violence towards animals.

This added a new moral weight — and an elevated sense of pressure — to my work. Every second of every day, thousands of animals were being starved, crushed, and boiled alive. And every moment of my own pleasure, that philosophy paper reminded me, was another second I wasn’t doing anything to intervene in this suffering.

While my anxiety and moral urgency grew, so did my arrogance. I’d accuse people in my life — at times silently, and other times overtly — that they “weren’t doing enough.”

I solidified a belief that shadowed over how I saw myself and others: If I don’t work as hard as I can for the animals, I am a moral failure.

Then I burnt out.

A painful breakup later that year left me emotionally devastated and unable to continue my work. It revealed deeper cracks in my personal life — that my total focus on animal rights had left me precariously unsupported in a time of emotional need. I had undermined my friendships and neglected my mental health.

Feeling broken, I had little choice but to quit.

A burnout-turned-world adventure

So I left my job and decided to travel around the world.

My colleagues graciously celebrated as I took my first break from activism in years. It was time to get some perspective. And it was wonderful.

Over the next few months, I visited old friends in Mexico City, sang karaoke in the Philippines, and camped with forest hippies in Taiwan. It was thrilling exploring new parts of the world, getting distance from my old life and learning from ones anew.

But a few months in, a familiar feeling grew stronger and stronger: that my time traveling, despite being prompted by a need for perspective and personal recovery, were selfish.

For the first lengths of my travel, I would casually pitch Singer’s moral dilemma to fellow travelers. “Hey, what do you think of this thought experiment…?” But over time, I brought it up less as a conversation piece and more as a personal obsession. Unsurprisingly, I was often met with uneasy body language and discomfort. “I don’t think it’s healthy,” at least one person said to me, “to be driven by so much guilt.”

The fact that no one could give me reasons why Singer was wrong led me to become even more confident in my moral beliefs. I saw every conversation as confirmation that there were no perspectives, even globally, that could undermine his simple logic. I more and more understood myself as a rare person who was able to handle the discomfort of what morality demands of us.

Then I found my confidence dislodged by a familiar perspective. I befriended a young traveler in a beach-side hostel in Taiwan. She was a climate activist from the Netherlands who was very familiar with senses of urgency and catastrophe. She interrupted me as I frantically explained the drowning strangers dilemma. “You are not responsible for factory farming or climate change,” she said. “You can’t bear the weight of the entire world on your shoulders. You have to find some joy in life.”

I wasn’t convinced. If you encounter a child drowning in a pond, why would it matter whether you were responsible for putting her there? But I did know that on some level, she was right. I saw how emotionally consumed I was by the idea and felt a glimmer of shame at how I had wielded it with arrogance over those around me.

I tried more desperately after that to work out my thoughts. I scribbled furiously for hours into my notebook to find cracks in Singer’s argument. After weeks of spiraling contemplation, it became clear to me that all that thinking wasn’t doing me, or anyone else, any good. This wasn’t a rational dynamic — it was an emotional one.

A turn within

From that point forward, I reframed my relationship to the vivid moral dilemma. I tried to understand not only the logic of moral obligations but also my emotions around them.

I turned my gaze inward. And with lots of meditation and the help of my therapist, I began to see more clearly the roots of what drew me so strongly to animals and to activism in the first place.

When I was a child, I lived with my older brother who has autism. He is non-verbal and, due to chemical imbalances in his brain, suffered deeply with near-constant confusion and anger.[1] Being around him blurred the line for me between human and animal and gave me a soft spot for difference — an impulse to protect the most vulnerable.

And then he was sent away. When I was entering high school, his condition worsened to the point of him having violent tantrums that regularly required my mother and I to tackle and restrain him. Later, in one example of his outbursts, he charged at my mom and, missing by only inches, nearly smashed her head into the corner of a marble countertop. Reluctantly, we called 911 — first once, then again and again. After a couple months, the state forced him into a mental hospital.

After that, I went through high school without seeing much of my parents. They both worked full time and drove several hours each day to visit my brother until visiting hours were done. I often felt lonely at home, seeing my family only when they returned late into the night. I struggled to do well in school. Occasionally, my mom would praise me, sighing with relief that I seemed to be doing okay. I never complained. I internalized a sense that to be a good kid is to “take one for the team” — to devalue my needs relative to others. So for much of high school, I sat at home, alone, believing deep down that if I couldn’t have attention, at least I could be good.

A return home

I am back home now after what feels like a year of solo travel. After Thailand, I continued traveling around Southeast Asia — through Laos, Vietnam, and one final month visiting old friends in Taiwan.

My eight months abroad were thrilling and painful. As a forced breather from my activist world, it was one filled with self-exploration and self-doubt.

Perhaps most importantly, my time and space traveling gave me the courage to tap into old wounds that had laid hidden for so long.

During my first week returning home, I opened up to my mom for the first time about my feelings of abandonment. We talked about everything: the family trips longed for but never planned; the school plays unattended because of an emergency at home; the hurt I never voiced because I believed I had to hide it from my mother; the resentment I carried unknowingly into adulthood because of the deference I gave to my brother.

I explained to my mom how I became avoidant as an adult, fearing closeness with people out of an unspoken fear of abandonment. And I unpacked the moral anxieties that laid under much of my activism.

She cried. I cried. My mom told me that she now understood why for years I’d pushed her away. After that conversation, I noticed my inner child finding the softness to forgive, and to finally have the bravery to open up to her. I call her on the phone regularly now with an ease that I‘ve never had before. And it feels that for the first time in my adult life, I finally have a real relationship with my mom.

—

So, where do I stand now on Singer’s thought experiment?

I still believe in the core principle: if we have the ability to prevent others from suffering without a significant sacrifice to ourselves, we should. Privilege carries with it a moral responsibility to act. But I believe now, too, that the reasons why we act can be just as important as the actions themselves.

My burnout taught me that tying one’s self-worth to one’s good deeds is a dangerous place to be. Our life circumstances will, at times, knock us out of the patterns that we use to find validations in ourselves. The actions that we rely on to justify our existence can and will be wrestled out of our control, at which point we will have nothing left to say we are good; nothing left to tell us we are worthy.

To me, this is not a story of “I worked too much and burned out.” Hard work is essential to some of the deepest beauties in this world, including caring for loved ones and the most vulnerable. Rather, this is a story of how the work we do can burn us if done for the wrong reasons — in my case, to patch over the vulnerability I never fully expressed to myself.

Now, I am back to organizing campaigns with The Simple Heart and inspired once again by the activists of the SF Bay Area. Their determination for animals reminds me that hope is far more powerful than guilt; inspiration more resilient than fear. And that inspiration will flow most naturally when our care for others is matched by a healthy care for ourselves.

The psychologist Kristen Neff writes, “Compassion isn’t a zero-sum game. The more compassion that flows inward, the more resources we have available to be there for others.”

I hope each of us is able to find that self-compassion — for the sake of ourselves, for those we care about, and for the world.

—

Thank you for reading. If you’re struggling with burnout and guilt, feel free to reach out to me to connect. I‘ve also benefited from this article on impact obsession from the EA Forum and Self-Compassion by Kristin Neff.

The book Strangers Drowning is the most direct exploration I’ve found of guilt and Singer’s thought experiment. It narrates the lives of several people who have struggled through questions of moral responsibility and dedicated their lives to social impact. It’s an easy read that’s been taking me a long time to get through — as all true “fixes” do.

- ^

I don’t know if this is exactly how his condition worked, but it is how I understood it.

SummaryBot @ 2026-02-11T17:28 (+2)

Executive summary: In this reflective essay, the author recounts burning out from animal activism driven by guilt and moral perfectionism inspired by Peter Singer’s “drowning child” argument, and concludes that while the core moral principle still holds, sustainable activism requires self-compassion and motives grounded in care rather than self-worth.

Key points:

- The author became deeply committed to high-risk animal advocacy, influenced by Singer’s “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” and the “drowning child” thought experiment, internalizing the belief that not working as hard as possible made them a “moral failure.”

- Legal wins, national media coverage, arrests, and association with prominent activists intensified both moral urgency and personal pressure, while cracks formed in the author’s personal life and mental health.

- A painful breakup and emotional exhaustion forced the author to quit and travel for nearly a year, during which guilt about not intervening in suffering continued to dominate their thinking.

- Conversations abroad, especially with a climate activist who challenged the burden of total responsibility, exposed that the author’s fixation was driven more by emotional dynamics than purely rational reflection.

- Through meditation, therapy, and confronting childhood experiences of neglect and self-suppression related to a brother’s severe autism, the author recognized that their activism had been tied to self-worth and a learned habit of “taking one for the team.”

- The author now maintains Singer’s core principle that we should prevent suffering when we can do so without significant sacrifice, but argues that activism grounded in guilt and self-validation is unsustainable, and that self-compassion strengthens rather than undermines moral action.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.