Carolyn Henry: Eliminating Parasitic Worm Infections

By EA Global @ 2019-03-18T14:57 (+15)

This is a linkpost to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLHh-OOe14k&list=PLwp9xeoX5p8OpYjWpNDQnjyTpoelQmy4P&index=3

Schistosomiasis affects about a quarter of a billion people worldwide, particularly people living in some of the world’s poorest countries. In this talk from EA Global 2018: London, Carolyn Henry of the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative talks about SCI’s work against the disease, the value of buy-in from the recipients of their aid, and the importance of mentoring local government officials.

A transcript of Carolyn's talk is below, including questions from the audience, which CEA has lightly edited for clarity. You can also read the transcript on effectivealtruism.org, or watch the talk on YouTube.

The Talk

Eight years ago, I started working for Médecins Sans Frontières, and I was placed in Nigeria. I was super excited to go out for the first time, to feel like I was doing good firsthand as a nurse in a very remote clinic in Zamfara State, which is near the boarder of Niger. The project was for children under five and there was a great need there, because at the time there had been an environmental impact which had resulted in lead poisoning, causing thousands of children to die and a lot more to be developmentally challenged. On top of that, there was the usual malaria, with its massive problems, and also outbreaks of cholera and annual outbreaks of meningitis. So there was a huge burden of poor health and mortality in the area. I turned up to manage the local hospital and the outreach clinic there, and was expecting people to be as excited to receive the treatment as I was to give it. But it was actually quite difficult to get people to come to the clinics. They were a bit suspicious about even the world-class meds that had been specially produced for this lead poisoning. They were quite suspicious of that, and also obviously suspicious of us coming in from the outside to their very rural community.

And this came to the forefront of my mind when I was sent to go to an outreach clinic, where we were looking to see if we could expand the scope of the project. We went to see the local health center, which as you can imagine was very resource poor. It was not providing high quality service to that community. But when we were there on that day, there was also a traditional medicine man who was traveling through the village. People were queuing up to go and pay quite a large proportion of their income to get herbal teas, which they believed would cure them, rather than the medicines that we would be able to give them for free, that were evidenced and effective. This really struck me, really in the face, about how it was so important for not just me to know the evidence and to know the effectiveness of the medical care, but about that community and how we can empower them to ask for that treatment themselves, and to get the medical care they deserve.

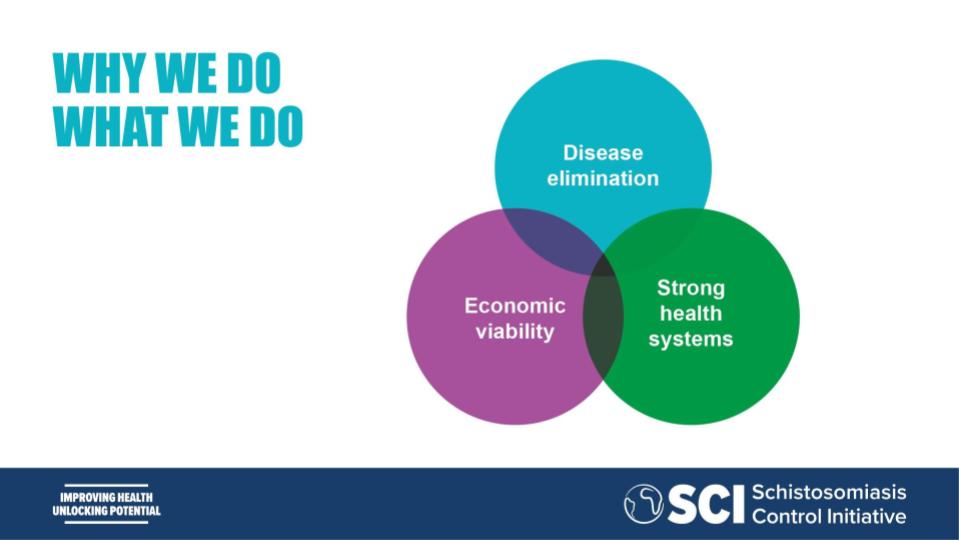

Fast forward a few years, I now work for the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. I'm a Senior Program Advisor, mostly working in Ethiopia and Tanzania. SCI has just going through a strategy change. We've got a new strategy out this year. And now we are really focusing on that exact point, is how do we empower local communities? Not just delivering our signature, a cost effective treatment program, but also articulating more about how we do that, and how we are able to empower not just national governments to have ownership of their projects, but also local communities.

I'm going to just talk a bit about our strategy and our challenges. We'd love some feedback from the EA community, and input to make our projects as good as possible.

For those who are not familiar with SCI, we work in 15 Sub-Saharan African countries. We are delivering treatments for parasitic worm infections, mostly focusing on schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths, or for short, schisto and STH. We deliver those programs through national governments, so we don't directly implement, but rather support national governments to deliver their own programs through their existing health systems. We're really trying, in our new strategy, to better articulate our approach. So how we do things, not just what we're able to achieve at the end of treatment.

One of our big things we want to emphasize, though we've been maintaining them for a long time, is our partnerships. Looking at the partnerships and collaborations with other sectors like water sanitation and hygiene, and also other sectors like education and nutrition which are overlapping as well. But also, we really want to show how we're working through the partnerships with local governments, to make our work as effective as it can be. We are also looking at our own processes and procedures, making them as effective internally, but also making them accessible for the countries and governments with which we work, so they can have their own embedded knowledge management systems, and they can mentor some of the approaches that we might use as standards, and learn procedures they might not have otherwise known about. So we're really keen to put some innovation into each country's programs.

We're also trying to keep a sustainability element. Schistosomiasis in particular is not going to go away very quickly. We're going to have to work for many years at delivering the mass drug administration programs. And then after that, there still needs to be a health system in place that can sustain the surveillance, so that these diseases don't just come back again. It's not good enough to treat until the rate goes down enough, because it will just come back up without the proper water sanitation, education, and behavior change. We need to make sure that local health systems are strong and robust to be able to sustain the programs now, but also to do the necessary surveillance in the future.

Finally, we are always evidence based. We're not only evidencing about the treatments for the parasitic worm infection, we also want to evidence the approach that we use to prove that it is a very effective method, and also just understand more about how we're connecting to existing health systems and strengthening them from them the inside. We want to understand, and to be able to articulate that better.

Here's a case study from Ethiopia, where SCI mostly works. So what happens at the beginning of the year is that the WHO, through a drug donation program, can deliver the drug so that the country teams are able to distribute them all over the country. We also get funding for the program from a variety of sources. So SCI is just one of those sources for the Ethiopian government. This year in total they've had hundreds of millions of tablets, and even just the sheer schisto and STH programs are over $6 million this year.

So what we do at SCI is support the national level governments. So thinking about the size of that program, there's only one person in the Ministry of Health that's responsible for the schisto and STH programs. So you can imagine the capacity that he has to be able to try and initiate, sustain, maintain that level of program on his own. It's a lot. And also he's been assigned to that position, rather than selected because of his knowledge on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs). So we are there to really support, mentor and coach in all the areas of the program, including leadership, where we're talking about advocacy and how to mobilize the staff at lower labels. We're training people, and thinking about how they can train others in turn. We're doing drug distribution and procurement. So making sure they have a good process of inventory, where the drugs arrive savely and on time. We make sure that the drugs are well stored for the people who need them, and figure out how to mobilize the community to make sure they come, and are aware of a drug distribution on that particular day.

And lastly, monitoring and evaluation. So we're really making sure that our beneficiaries understand the impact of the processes and of delivering those drugs. And then that relies on a cascade. So in Ethiopia, that one person at national level will train the nine regional NTD coordinators. They do all the neglected tropical diseases. So we have eight endemic in Ethiopia plus they'll have to do malaria programs and TB programs. So you can imagine it's a huge volume of work they have to do. So we need to make sure that the packages are very easily accessible and understandable, so they can understand, pick them up, and deliver a very good program that's safe. They will then train the district level coordinators. So we are working in over 550 districts in Ethiopia, and they will then train the health extension workers.

So this year we're doing over 22,000 health extension worker trainings, as well as training schoolteachers for awareness so that they can support the health extension workers. That's all to deliver over 8 million treatments for schistosomiasis this year, and 15 million for soil-transmitted helminths. And then we need to make sure that they can monitor and evaluate, but actually the impact of them being able to do that monitoring and evaluation is more about accountability. So they understand that they can go to the funders and report back to them, including us at SCI, to show what they have managed to achieve, and also really to take charge and ownership of that program, because they feel that buy-in from when they see that things have actually improved. So we use this program cycle to help ensure there's ownership and accountability.

So, of course, our ultimate aim is to have disease elimination of parasitic worm infections. But it's not as simple as just sticking to the WHO coverage target of 75% for school age children. We actually need to go above and beyond. So we're looking now at how we can reach those hard-to-reach children, the ones that don't go to school, that will receive the medicine at the school-based platform. We want to make sure that the children who are in refugee camps, who are nomadic, who maybe have to work from a very young age and are outdoing the agricultural field work, are still able to get those tablets every year on the de-worming date. But as well, alongside the disease elimination, we really want to make sure that there are strong health systems along the way. So we don't want to interrupt the health system by taking over or interjecting. We want to make sure that all the teams are learning alongside us through the whole journey, to make sure that institutional learning will persist for these national health systems. And we need to make sure that they're robust and resilient.

These countries often face so many disasters. For example, Liberia had to stop their program at some time for Ebola. And we managed to quickly engage them again, but we need to make sure that if there's flooding, national disasters or other disease epidemics, that countries from now on can continue their de-worming programs. And to be able to make sure that it's not always a standalone, externally funded program. We need to make sure that we can contain health programs to a size that they are more manageable and economically viable, so that the programs can then transition into the mainstream health system. And that's more likely to be the case when we perform a smaller proportion of treatments annually. And also definitely when we get into the surveillance stage, because the health system will need to maintain that surveillance level on their own. So this leads us to some of our challenges, like that we're really hoping that the governments will be able to think about their investment into NTD programs in general, but specifically schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths.

We want to make sure that there's the political will to engage with these programs, that people understand what the complexity of their health burden is on young people, and the impact that they can have from taking very simple measures. So we want to create the political will, but also we want to make sure that that not only comes from us externally, but also from the communities themselves. We want to make sure that those communities will be able to create demand on their own. If a train is late in the UK, people get on Twitter; they demand a refund. That's a strong public demand for quality service. But in the communities where we work, they don't even have any expectation of a health service, let alone a quality health service.

So that's what we want to make sure that the community knows, what is quality and what they deserve in a health system. And then we want to make sure that their health systems have that capacity not only to deliver the de-worming program now, but as circumstances change over the years. It may be we'll need reassessments, we'll need to evaluate the data, we'll need to make sure that we work alongside other NTD-control efforts, and also alongside the water and sanitation sectors. So we need health service teams to have capacity to be able to do that.

Now, our challenge is how do we transition from being a very cost effective organization who's horizontally scaled to deliver huge amounts of treatments with quite a small team, but having a big impact, to an organization that's embedded vertically into the health system, making sure we get all those hard to reach children and eliminate the disease? How do we make sure that the health system is strong enough, and that we've helped build the necessary capacity. So that is now our challenge, is to think about how we can effectively measure and also articulate what the value add is of our approaches and our processes.

Questions

Question: What is schistosomiasis? What happens when you get it?

Carolyn: Yeah, so it's a parasitic worm. When children have the disease, it can be either in the bowel or the bladder. So there's two different types, but they're both treated with the same medicine. And the way that it's transmitted, we call the life cycle of that particular worm. It's found in a fresh water lake. So if a person goes into the lake, there might be some snails in the lake. And they produce what we call cercariae. The little cercariae can mingle inside the skin. They're so small, they can just slip inside of the skin, and then they will go through the system and enter either the bowel or the bladder. The burden of disease is seen mostly in school-aged children, because they're smaller, so they feel the effects more strongly. It can produce a variety of different conditions.

Some of them you might not see initially. So that's one of our challenges, is that people sometimes don't know that they're ill, or don't immediately see the consequences of the disease. They're not thinking, "I want to go and take medicine for that." So some of these diseases can actually... the impact of the disease can actually lie dormant for quite some time. And the way it goes back into the lake is through open defecation or through being passed from either the urine or the stool back into the lake. The snail is what we call an intermittent host. Then it produces the cercariae. The cercariae go back into the skin. So things like access to water are what makes schistosomiasis so different from other parasitic worms. It's not as easy as saying, get some toilets for example, because if the cercariae is in the water, and you've got nowhere else to wash yourself or your clothes, or if your livelihood is fishing, then you're always going to be contaminated by that water.

So it's quite a challenging problem in terms of the causality, but also the burden of disease, which is not seen immediately, which won't cause people initially to go and get access to medical treatment.

Question: So ultimately, neither medicine nor sanitation alone can really solve the problem?

Carolyn: Yeah. So we sort of think about it like a three legged stool. There's a part about the these snails as vectors, and thinking about intermittent host control. So the question of whether there's anything we can do in terms of the lakes and understanding the snail as that vector.

And then there's also the part about the water and sanitation, but it's not as simple as just having the toilet or just a little bit of water. It would have to be on such a scale that people wouldn't need to have the contact with the water at all, or they would be able, for example, if they're fishermen, to be able to protect themselves against that risk and understand the risks so much they can wear certain boots to protect themselves from the water.

And then there's mass drug administration, which is the most cost effective way for the control of the disease as a public health problem. But when removing to think about elimination of that disease, yes, you're right. You have to think about everything together.

Question: So I was reading a little bit just as you were talking also on Wikipedia, this affects 250 million people annually. This is with your organization working on it, and presumably others?

Carolyn Yeah, exactly. And they're all in the poorest countries. So at the moment we're aiming for control of the disease.

So people are still affected, but they wouldn't have the burden of the disease, because every year they'll get treatments through their schools. So we are bringing down that burden of disease. But in our new strategy, obviously we know that ultimately it's not enough just to control. We're now pushing toward elimination. So that's where you have to think of that extra mile. How do you not just control? So the WHO recommends 75% coverage of all school aged children to control the burden of disease. But when we're thinking about elimination goals, it shoots up to above 90% coverage. So that means we need to be thinking of those hard to reach children. And actually we don't really know where they all are; they're not in a census. So we don't know exactly how many we're talking about or where those children are. So that's a lot of the research we're doing at the moment.

Question: Has 75% coverage been accomplished? Is it the reality in a lot of the places where you're working?

Carolyn: So that's what the WHO and all the evidence proves, that the 75% coverage is necessary for the control of the disease. However, like any evidence, you could actually ask "how do you know it's 75%" if maybe you don't have an accurate census to make sure your denominator is right. So it's like any research. You can find ways that you would argue the point. But definitely the overwhelming pool of evidence that's out there shows that there's a great impact on people's lives by reaching 75% coverage.

Question: What does the team look like? What are you guys doing day to day? If we were to observe your work, what would we see and what sort of skills do you feel like are missing from your team that you would love to add to be able to extend your work?

Yeah, so that's interesting. So at the moment we have four main teams. So I'm in the programs team, and we are program advisors. So we have two or three countries each that we go out to regularly. So for example, I sometimes go once a month to Ethiopia for about a week, or sometimes I just go for training to help or specific times during when the drugs are being given out. So day to day we're either in the office catching up with the rest of the teams or we are out in our countries, maybe about 30% travel time for most of us. And then there's the monitoring evaluation and research team, which has got bio-statisticians, social scientists, and an economic advisor, so value-for-money officer. And they support the country programs mostly through us as the program advisors, and they would help with all their statistical analysis of the data that we bring back, particularly about impact reports, and coverage validation. But they don't just do it for us. They also travel to the countries to help us train in-country teams. So eventually those people can do it themselves and build that skill. And then we have a finance team to support us, and also a communications team to help articulate our work. So we're at about 25 people total.

In terms of more skills that we would like, I think we're at a really interesting point, where we could scale a lot and that's evidenced when GiveWell does their assessments. We're ranked second by GiveWell as the most cost effective nonprofit initiative. When we're looking at the roles, I think we could go so many directions, but it's how we're at the tipping point that we've got a core team of roles and people that we need, but at different points we are thinking more about the social science aspect. So we've got one social scientist, but we could do so much in that field. It also thinking about, do we either collaborate or have consultancy about wash experts, to help us think about that a little more? But mostly I think we're in a really nice position where the community that work on neglected tropical diseases is very good at collaborating. So often we do get skills just through collaboration with either research or different organizations.

Question: If I understood correctly, as an organization, you're trying to make a shift from a pretty narrow, well-defined set of programs that you're supporting to an institution building type of challenge. Is that right?

Carolyn: So I think that rather than a shift, it's more like an organic movement that's probably happened from the beginning. And it was something we were always known for, the Program Advisors, including people before me, have had very good relationships with the governments that we work with. So actually I guess rather than a shift, it's more just thinking actually, this is what we do, and it works really well. So how do we evidence it? How do we articulate it and how do we measure it to really encapsulate what the whole program is? Yeah.

Jemma @ 2019-03-19T11:13 (+2)

Correction: article summary says "quarter of a million" but article makes it clear it is 250 million, i.e. "quarter of a billion". Feel free to delete this comment. :)

EA Global Transcripts @ 2019-03-20T02:07 (+1)

Thank you for catching the typo! Would that it were true.