David Manley: Decoupling — a technique for reducing bias

By EA Global @ 2020-10-25T06:56 (+7)

This is a linkpost to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GNBIsChKWpc&list=PLwp9xeoX5p8OoBBqv8t7JhVcgbjtXq3f7&index=18&t=882s

Overcoming confirmation bias in our thinking requires decoupling: evaluating the strength of new evidence independently from our prior views. David Manley, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan, explains in this EA Student Summit 2020 talk how to implement some easy cognitive techniques that have been shown to help us successfully decouple, and how even informal decoupling approximates Bayesian reasoning.

Below is a transcript of David’s talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube.

The Talk

Melinda Wang (Moderator): Welcome to this session on decoupling, a technique for overcoming bias, with David Manley. I'm Melinda Wang, and I'll be your emcee. We’ll start off with a pre-recorded talk by David, and then transition to a live Q&A session where he'll respond to your questions.

Now I'd like to introduce you to our speaker, David. David Manley is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor. He teaches at the graduate and undergraduate level on a wide range of topics in philosophy. Here's David.

David: Hello, everyone. My name is David Manley. I teach philosophy at the University of Michigan, and I have started to teach a critical thinking course in the last two years. I looked all over for interdisciplinary work on the most systematic ways in which we make errors in our cognition, then tried to find tools that can help us overcome these errors. I put those together in a book called Reason Better [log in as a guest to read the book online].

This talk is about a tool that I think is one of the most important [ways to overcome cognitive errors]. It's called “decoupling,” and it’s especially helpful to us [when we face] something called “confirmation bias.”

You've probably heard that term. [I define it as] the tendency to acquire and evaluate evidence in a way that supports our preexisting views.

These preexisting views don't have to necessarily be things that we really want to be true, or are attached to. They may have just popped into your head and you found them plausible. Then you start to notice things that fit with your beliefs — things that sort of make sense — and you don't notice things that disconfirm them as much. This is one of the ways that confirmation bias works. And when we interpret evidence, we do so in a way that matches the idea that we already think is probably true.

There’s a lot of great evidence on confirmation bias. I should say that confirmation bias tends to be worse when we have some motive for a preexisting belief. For example, let’s say there are several people who have varying beliefs about an assertion like “capital punishment deters crime,” and you ask them, “How confident are you that capital punishment deters crime?” Then, you give them a pile of evidence [supporting] both sides. Maybe one study [claims it does deter crime] and another study [claims it doesn’t]. Then, you ask, “Now how confident are you about the belief that you started with?”

You might hope that, since you provided some evidence that went in both directions, they'd be less confident. But actually, almost everybody will be more confident in the belief that they started with. And in general, people are twice as likely to say that, on the whole, the new mixed evidence supports the view that they started with more than the other view.

Most of the time there's mixed evidence for things like this, so it's very hard to get people to dislodge a belief that they already hold. This can be the case even if they're not particularly attached to it.

What's really interesting about these studies is that people are trying hard. They are carefully examining the opposing evidence. If you give the test to undergraduates who know about the methodologies used for studies, they'll pick apart the opposing study, yet say, “I'm being extremely fair. I just never realized how weak the evidence is on the other side.” And when you say, “Look, there's a thing called confirmation bias. Let me tell you about it — people who participate in this study almost always end up more confident in the view that they started with. Read the studies and see what happens.” And people [complete the reading] and say, “I know you're going to think this is confirmation bias, but it just so happens that in this case, the evidence that you gave me, on the whole, supports my view more. There are more problems with the study on the other side.”

This is what we're dealing with. Confirmation bias is a very hard thing to overcome, and part of the reason why is that we don't see it happening. It'd be very convenient if you could just decide to believe something, but it doesn't work like that. We don't want to see that we're affecting the way that we think, and, for the most part, these processes are going on sort of “under the hood.” They're not open to our introspection.

Therefore, the idea that you can just check your motivations to see if you're being biased [is flawed]. This is called the “introspection illusion.” What's particularly pernicious about this illusion is that you think you're not being biased because you don't feel like you are. It feels like you're being really fair. You see that your opponent is looking at the very same evidence and coming to a different conclusion. Then you think, “Wow, that person must be biased because they're coming to a different conclusion from the same evidence. What's more, they should be able to tell that they're being biased by introspecting; therefore, they're being dishonest somehow with themselves or with me.” So of course, this generally leads people to think that their opponents are somehow arguing in bad faith.

Although we can't just directly look inside ourselves and see how biased we're being, there are things that we can do to step back and ask ourselves, such as “Am I in a situation where I might be in danger of confirmation bias?” I think it's very hard to do when you're evaluating evidence.

One thing you can do is notice signs of attachment, because attachment does make confirmation bias worse. Do you feel hungry for evidence — like, “Oh look, there's a piece of evidence that supports what I think”? Do you flinch away from information that might be evidence on the other side? If there's a thread sticking out of the sweater, so to speak — something that just doesn't feel quite right — do you yank on that thread to see where it's going to go like you would if it was in your opponent's sweater? Or do you just let it go?

[Just letting something go instead of being] really curious about whether it’s true is a sign of attachment. It's not that I think we can or should avoid attachment. Of course there are things that we want to be true. It's just that we have to be especially vigilant in those cases, and try some of the techniques (which I’ll talk about) that can help us overcome confirmation bias.

Another thing that we can do is look for something that Jonathan Baron has called “belief overkill.” [See also Gregory Lewis’s EA Forum post on “surprising and suspicious convergence”.] Belief overkill is essentially when all of the considerations seem to fall in favor of the viewpoint that you happen to think is right. It's not just that veganism is more humane and better for the environment, but once you've started to adopt veganism, you notice that some people say it's better for your health than any other diet, including the Mediterranean diet. Some people say it's better for your cognition (although you might worry a bit because you’ve heard that creatine increases cognition, but who knows). And veganism feels like maybe it's better for your sex life; you’ve heard that it makes people smell better.

So if you start to think that all of the considerations are in favor of veganism, that might be an indication that at this point we're just collecting ammunition [for our own point of view]. We’re looking for an arsenal of reasons; it’s not genuine curiosity about the truth. Because these things don't really hang together. There's no reason why, in addition to it being the most humane diet, it should also be the most healthy and help your sex life. Those are totally independent things. It seems very, very lucky that they all fall in the same direction. And you don't need them to all be true if you're vegan. Probably the fact that it's more humane and better for the environment is adequate.

If you notice belief overkill, that’s another reason to be especially vigilant. I’d also add that never having changed your mind about something since you were six years old is maybe a bad sign as well.

So what's going on with the evaluation of evidence when we're affected by confirmation bias? We think that something's already true. When new evidence comes along, it seems weak if it goes against what we already think — and strong if it fits with what we already think. Even if we're not motivated [to take one side over another, we look for evidence confirming] how we think the world is.

This is pernicious. Just imagine a case where I think that there's a 50/50 chance that a particular claim is true. I encounter a piece of really strong evidence for the claim and a piece of really strong evidence against it — equally strong evidence [on either side]. But if the evaluation is biased, I might take only the first piece of evidence. I become fairly convinced that the claim is probably true, and then when I look at the second bit of evidence, it seems like it's probably not that good. It's not very strong evidence because of the effect of confirmation bias. Therefore, I probably end up thinking the claim is still true.

[Alternatively], if I had seen the other bit of evidence first, I'd think the claim was probably false, and then I’d think that the evidence in favor of the claim was probably bad, and end up thinking the claim was probably false. But the order of the evidence shouldn't matter. We started off 50/50. We viewed two bits of evidence that were equally strong. We really should end up at 50/50 again. That's why it's pernicious to let our prior confidence affect how we evaluate the strength of evidence.

So what do we do?

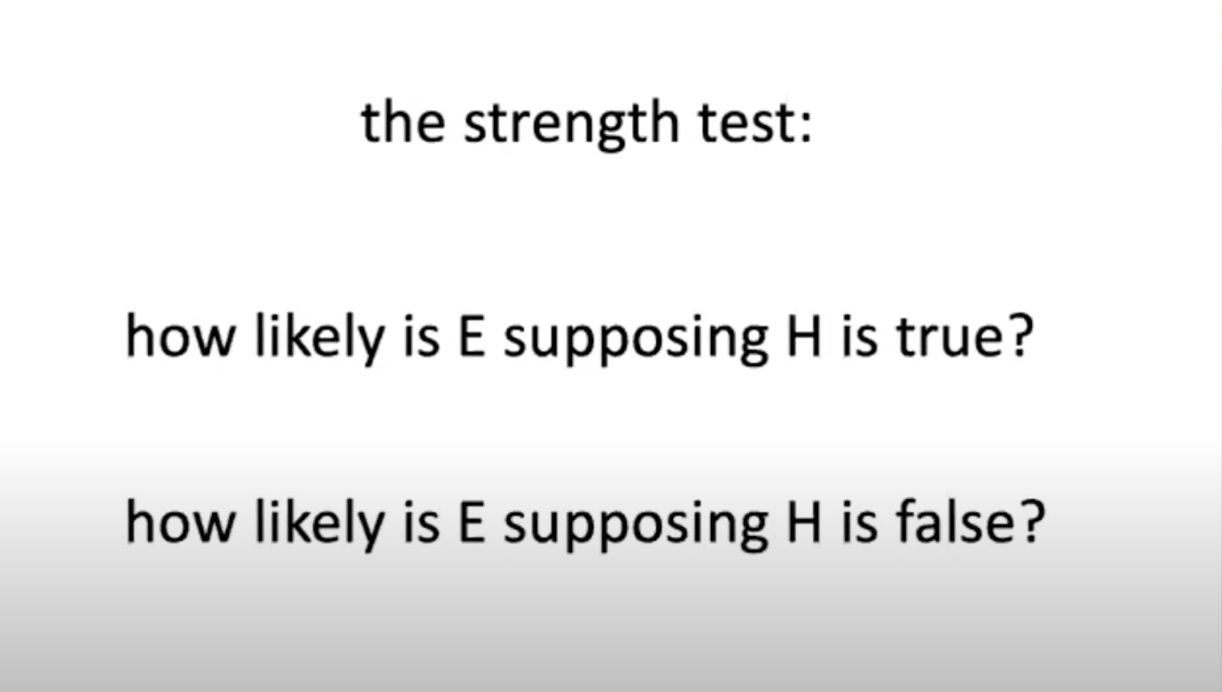

The way to test the strength of evidence is to completely set aside whether the hypothesis is true. Let’s say we're considering whether a potential bit of evidence [supports] Hypothesis H. Completely set aside whether or not H is true. Ask two hypothetical questions:

- Supposing H is true, how likely is it that we would have observed this fact?

- Supposing H is false, how likely is it that we would have observed this fact?

In the literature on gathering and updating evidence — if you look at statistics on epidemiology, etc. — this is the gold standard for the strength of evidence.

You may have heard of p-values. But in fact, the strength of the evidence is expressed as a ratio of the two values [resulting from the questions above], which is called the Bayes factor. I'm going to call it the “strength factor,” or just the strength of the evidence. It gives us all of the information we need to know about the strength of the evidence we're using. And it has nothing to do with whether we think H is true or not, or with how confident we are in H. I guess if H is a logical contradiction, then that causes problems for this test, but in all other kinds of cases, we can ask these two purely hypothetical questions.

For example, let’s say I'm wondering whether my friend is at home. I notice that his lights are on, and I think, “Is that evidence that he's home?” If my friend leaves his lights on all the time, regardless of whether or not he's home, then it's not evidence; the observation is just as likely to mean he’s not home as he's home. If my friend is super conscientious and always turns the lights off when he leaves, and always keeps them on when he's home — he’s a creature of habit in that way — then the lights being on is very strong evidence that he’s home. If my friend is pretty uncareful about these things, then it might be [weak] evidence that he is, and so on. We're just asking how likely it is that you'd leave the lights on if you're home and comparing that to how likely it is that you'd leave the lights on if you weren't home.

I'll be showing how to integrate these two things to come up with a new degree of confidence after gathering evidence. That's the subject of my next talk, “Gentle Bayesian updating.” (By the way, you don't need any mathematical background to follow that talk. It's a very gentle introduction.)

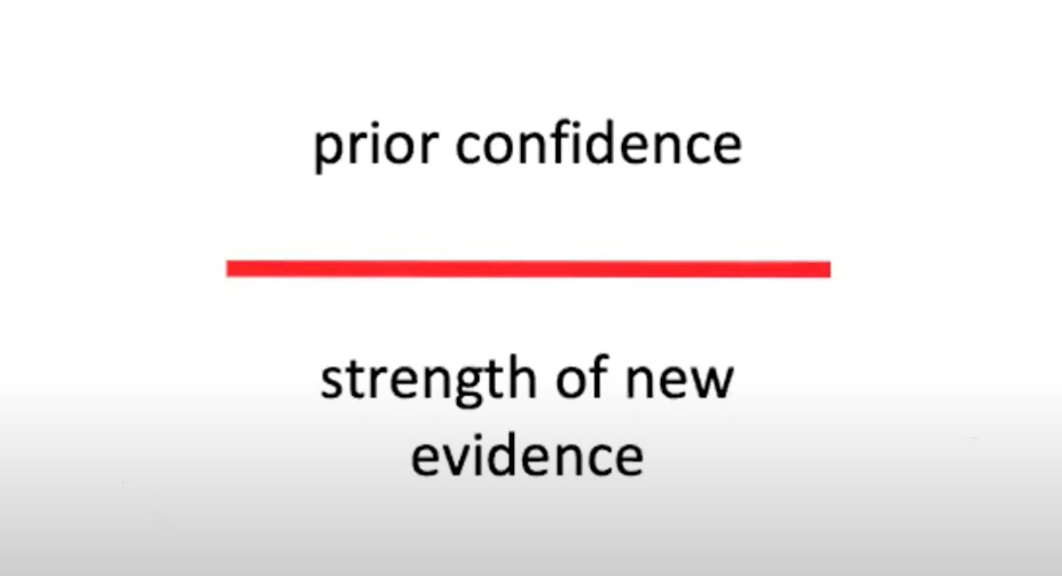

The key thing here is we need to decouple our prior confidence from the strength of the new evidence — that is, we need to evaluate the strength of the evidence on its own and not in a way that's colored by that prior confidence. Eventually, we're going to put them together to [arrive at a new level] of confidence.

But the tricky thing is that you can't just tell people to decouple and not allow their prior confidence to affect how they evaluate the evidence. That doesn't really work as a strategy because of the introspection illusion and something called the bias blind spot where we don't notice that we have a bias, even if we've been told about the existence of this bias and the fact that almost everybody has it.

Practically speaking, what can you do? There are some things that work. If you run one of those studies where you give people mixed evidence and then watch how their beliefs are affected, rather than telling them to try not to be biased, you might say: “When you consider this piece of evidence, ask yourself how you would have responded to that evidence if you had the opposite view.”

[Or think of what you could do if you were in that situation.] Suppose you review a piece of evidence and just think, “Ah, this isn't a very good study. It goes against the view that I had.” And then you ask yourself, “How would I have treated this study if I had the opposite view? Would I have treated this as pretty strong evidence?” Then it becomes a little harder to treat whatever little flaws you may have found [in the study] as super important.

Or, from the [opposite angle], let’s say you find something that seems to support your point of view, and you think, “This is wonderful,” but then you ask yourself, “How would I look at this study if I held the opposite view? I probably would've tried to find some flaws.” That might help you notice some flaws you wouldn't have found otherwise.

There's another similar approach. Rather than asking what you would have thought if you had the opposite view, ask yourself, “What if this particular study actually came up with a different result [than the one I favor]? Would I have evaluated the methodology differently?” You might acknowledge to yourself that you would have found some flaws in the study, treated the evidence a little differently, or not have endorsed it so wholeheartedly — instead worrying about who paid for the study, maybe.

From a Bayesian standpoint, this strategy forces us to decouple the way that we evaluate the evidence from our prior confidence. It forces us to do what is really required to evaluate the strength of the evidence: step back from what we actually think is true about the hypothesis and just evaluate the evidence on its own merits.

Of course, we're not just going to forget about past evidence. We should integrate those two things [the new evidence and the past evidence], as I describe in my next talk.

Thank you very much. I'll take questions now.

Q&A

Melinda: Great. Thank you so much for that talk, David. We're going to get started with some of the questions here.

The most up-voted question alludes to “System 1” thinking [our quick, instinctual reactions] and “System 2” thinking [a slower, more deliberative approach]. How can you distinguish between the two states? You may be an amateur at analyzing evidence. So you may be more prone to confirmation bias, as you mentioned. But when you're an expert in a particular field, your gut reaction [might be a better signal of the quality of an argument]. How would you be able to distinguish between those two states?

David: This is a great question, because we sometimes think that we should overlook System 1 and always override it with System 2 — the more conscious, deliberate, aware system. But there is something called skilled intuition, which involves making really fast and accurate gut judgments [based on] recognizing learned patterns. People who have a great deal of experience in certain environments may offer really quick, clear, reliable feedback. They can develop skilled intuitions where they might recognize that something is going on. Maybe you're a doctor and you recognize something going on in a way that you can't quite articulate. Those kinds of skilled intuitions do exist, but they really require special environments, and I think we're very often not in those environments.

Most of the people who think they have skilled intuition of this kind actually don't. Ask yourself: Have they been in environments where, over and over and over, those gut reactions have been tested and the person has received clear, quick, reliable feedback?

Somebody in the [livestream chat] also mentioned that you can test the reliability of these intuitions using calibration. If you start to feel that something is 80% probable, for example, over and over, write it down each time — and then see how often it turns out to be true. If it's about 80% of the time, then your calibration is right on target. But unfortunately, I think that most of the time, when people believe they have something like skilled intuition, they don't, or at least we should be very careful.

Melinda: It seems like the development of skilled intuition is something that's habit-forming. You have to come to it deliberately. You access it initially, but then it becomes incorporated into [your behavior] as an intuitive process. What are some concrete ways that you'd propose to students for them to make this a more habit-forming practice?

David: Well, if you want to develop skilled intuition on some topic, check every time for clear, quick, reliable feedback. It might be ambiguous. For example, people who are predicting the stock market moving up and down will say things like, “Oh, it's going to move up,” and then if eventually it moves up, they say they're right. So you need to make predictions with clear deadlines and clear outcomes, [to ensure that you’re truly] checking to see how reliable the feedback is.

But for many kinds of things, we don't get that kind of feedback. So there's no way for us to develop skilled intuition.

Melinda: That segues into a question that was posed about implicit bias. What are some ways that we can tackle implicit bias — or can we?

David: It's a bit of a tricky issue. The term “implicit bias” refers to a set of associations that can be tested. You can go and look up the implicit bias test. It's difficult to know exactly what [the results] mean. For example, in these tests, Black people often appear to implicitly associate being Black with negative attributes. That doesn't mean that they're racist. It might mean that their brain is aware of a [stereotype] that exists. So I think it’s very hard to know exactly how to measure [and interpret the implications of] implicit bias.

As for overcoming it, there are ways in which we can sort of quarantine ourselves from certain information that might bias us. For example, if you're looking at several job applications or resumes, you could try to quarantine yourself from facts that might bias you in one direction or another, and that aren't relevant to the person's abilities.

You can actually take an implicit bias test immediately after having called to mind a paradigm, a sort of anti-stereotype paradigm, and if you do that, then typically the bias [shrinks or disappears] for a time. So that's another thing that you can do if you're worried about implicit bias in particular cases: call to mind an anti-stereotype that will help reduce it. Basically, you can try to deliberately explore your own cognition and go from there. But it is tough.

The best thing to do if you think there's a fact that could be biasing you is to blind yourself by selectively picking out certain information to consume. That's probably the best approach, because we can't see the ways in which biases affect our cognition.

Melinda: It’s a really challenging problem. [Audience member] Sam also asks, “Given that confirmation bias is a major issue in social media, in what ways do you think social media companies or the regulators overseeing these companies can use these techniques to overcome some of the biases that we experience?”

David: It's very tricky, because they are optimizing for engagement, and the things that engage us are things that appeal to our confirmation biases and make us think, “Oh, this is a great example of what I've always thought about those people on the other side.” Unfortunately, anything that optimizes for engagement like that is going to have the effect of just increasing our confirmation bias and putting us in echo chambers.

I'm not sure there's a way, given that that's the model that [social media companies use] for revenue. Barring using a different model like a subscription model, where they're not necessarily just trying to optimize for engagement all the time, it's difficult to know what else we would expect them to do. It's a similar situation with the news media.

Melinda: Given that we've run out of time, I'm going to take one more question about your guide to critical thinking. [Audience member] Martin asked whether it will stay accessible after the conference.

David: Yes. At least for the next six months or so, you'll be able to use that link. If you ever need it or it doesn't seem to be working, just let me know. You can email me at dmanley8@gmail.com.

Melinda: Wonderful. That concludes our session on decoupling. Thank you so much for attending, everyone.

David: Thank you.