Jasper Synowski and Clare Donaldson: Identifying the most cost-effective programmes to improve mental health

By EA Global @ 2020-08-21T21:36 (+15)

This is a linkpost to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mUXThf8Q0k&list=PLwp9xeoX5p8NfF4UmWcwV0fQlSU_zpHqc&index=7

Even though mental disorders account for a considerable burden of disease globally and appear to strongly impact individuals’ subjective well-being, the effective altruism (EA) community has spent relatively little effort on identifying the best giving opportunities within the area of mental health.

This talk provides an introduction to the Happier Lives Institute’s Mental Health Programme Evaluation Project (MHPEP), which aims to fill this gap. In this talk, Jasper Synowski introduces the research process to date and shares preliminary insights, along with limitations of the approach. He then discusses HLI's work further with COO Clare Donaldson.

For in-depth preparation, Jasper and Clare recommend reading this post from HLI on the EA Forum.

Below is a transcript of their talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and read it on effectivealtruism.org.

The Talk

Bridget Williams [Moderator]: Hi, everybody. I hope you are all having a great EAGx Virtual from wherever in the world you are attending. My name's Bridget, and I'm the emcee for this session, which is on identifying the most cost-effective programmes to improve mental health, with Jasper Synowski and Clare Donaldson of the Happier Lives Institute.

To start, we’ll have a 15-minute talk by Jasper. Then we'll move on to a live Q&A session, in which we'll be joined by Clare.

[...] Now I'd like to introduce our first speaker for this session. Jasper Synowski studied business psychology before starting his master's degree in public health. Over the course of his studies, he has interned with various organizations in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors, and developed a special interest in global mental health, subjective well-being, and capacity building. He has been actively involved in the community since 2017 and part of the Happier Lives Institute since its founding in 2018. Here's Jasper.

Jasper: Welcome to this talk on identifying the most cost-effective ways to improve mental health. My name is Jasper and I've been a volunteer research analyst with the Happier Lives Institute (HLI) since 2018. Today, I am going to talk about HLI’s Mental Health Programme Evaluation Project, or what we like to refer to as MHPEP.

Here’s a brief outline of what I’ll cover in the next 15 minutes:

1. Why mental health could be considered an important cause area by the EA community;

2. Our research process (I’ll focus on the process more than the results, because we're currently at step two out of three steps); and

3. Some limitations and lessons learned.

MHPEP is a mental health programme and evaluation project. It’s one of several projects that HLI is currently working on. In case you haven't heard of HLI, it is a think tank that was founded after EA Global 2018, and it's searching for the most effective methods to improve global well-being.

HLI currently has three full-time staff members. In contrast, MHPEP is almost entirely conducted by volunteers of HLI. More than 15 people have contributed to MHPEP over the last one and a half years. Thanks to all of them, today I can share some of our findings with you. At the moment, we have five volunteers actively involved in MHPEP, plus our COO, Clare Donaldson.

If you'd like to know more about the other projects that HLI is currently working on, feel free to ask any questions during the Q&A.

Why mental health?

Let me start with the question “Why [work on] mental health?” As a community, we like to consider the scale, neglectedness, and tractability of problems. So I'll start with the scale.

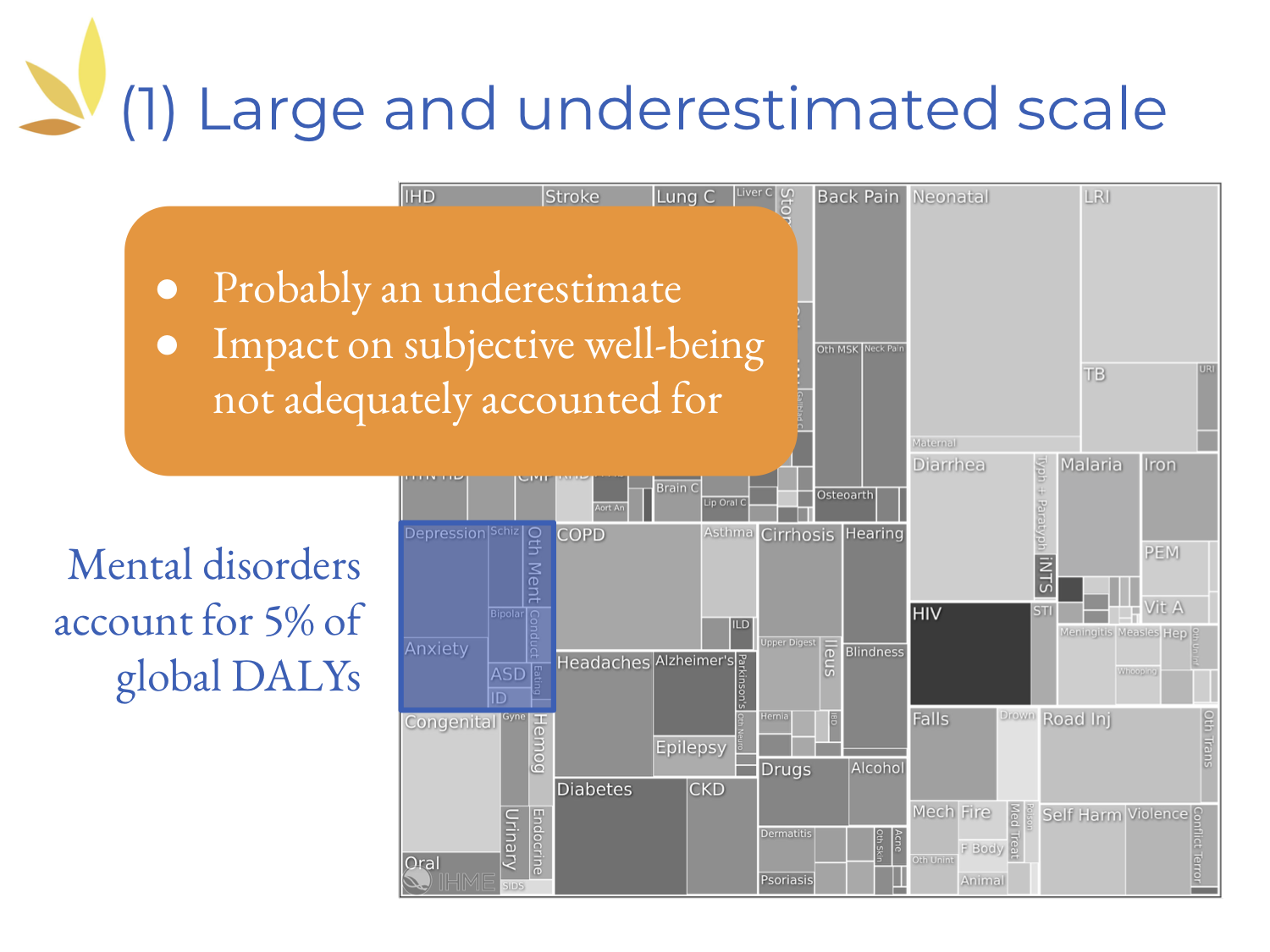

This graph shows the global burden of disease measured in so-called DALYs, or disability-adjusted life years. DALYs consist of both years lived with disability and years of life lost due to a certain disease or cause. So the size of the different rectangles that you can see here represent the burden of disease attributable to a certain cause or disease.

For example, in the top left corner you can see heart disease, followed by diarrhea, HIV, malaria, and violence. And finally, you can see that mental disorders account for roughly 5% of global DALYs.

There are a few interesting things to note. First, you can see that depression and anxiety are responsible for a large share of that 5%. To give you a sense of what that means, every year 264 million people suffer from depression and 284 million suffer from anxiety. It's also worth pointing out that substance use disorders are not included — and that 5% is probably an underestimate for several reasons, the most important one being that no years of life lost are attributed in this calculation to mental disorders.

In addition, the impact of mental disorders on subjective well-being is probably not adequately accounted for because DALYs are calculated using [self-reported] preferences — and people tend to underestimate how badly mental disorders affect their subjective well-being.

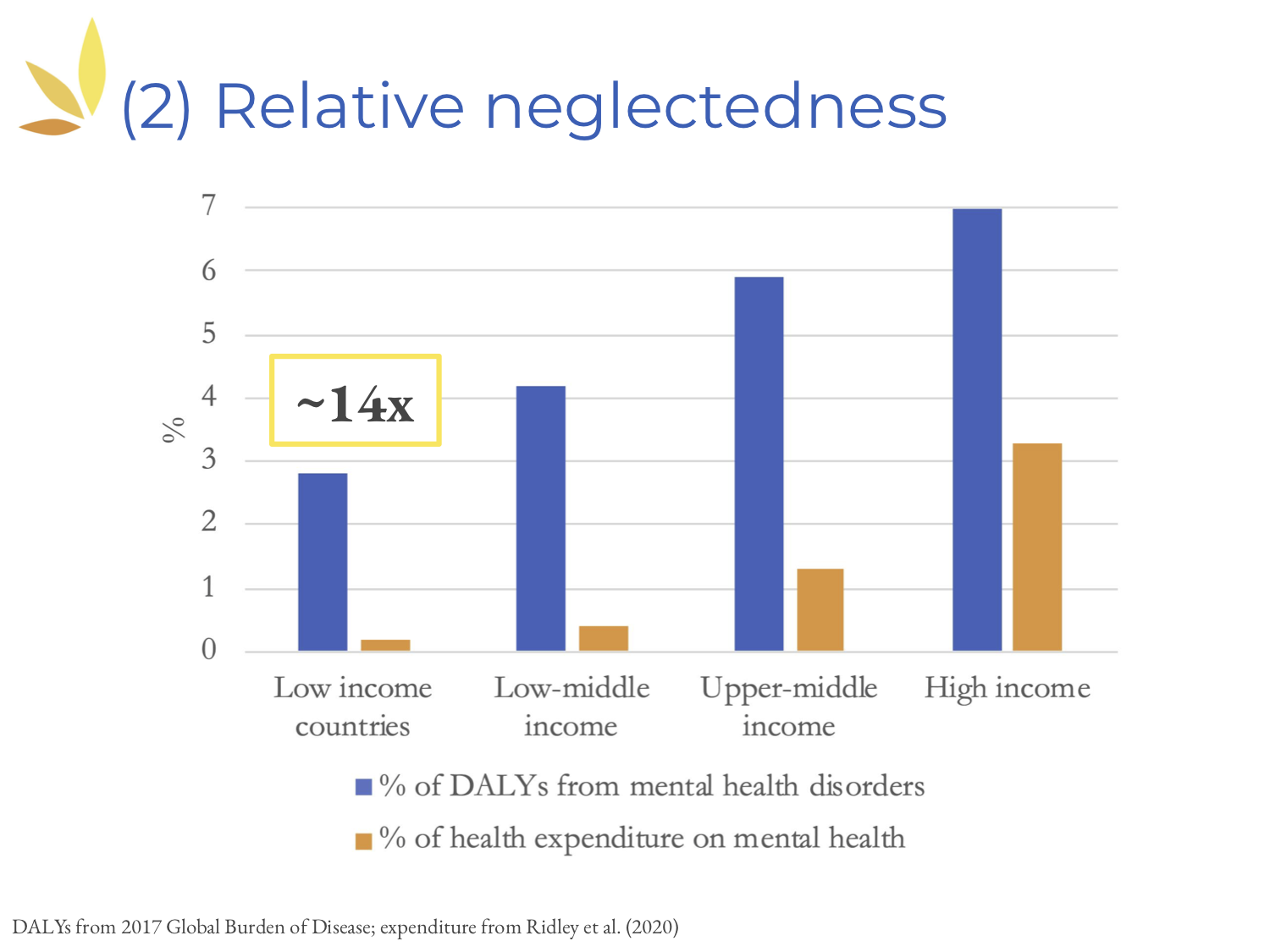

Next, let's look at neglectedness. This time, the blue bars [above] represent the proportion of DALYs attributable to mental disorders in different countries. These are compared with the proportion of health expenditure on mental health, shown in the orange bars. As you can see, in almost all countries, there's a huge discrepancy between the two. This is the most striking in low-income countries, where the factor is 14.

To add to this, it's interesting to look at so-called development assistance. Between 2006 and 2016, roughly 85 cents were spent on each DALY caused by mental disorders, compared to $144 spent on each DALY caused by HIV or AIDS.

Third, let's look at tractability. I would argue that tractable solutions already exist. I'll illustrate this by introducing two different programs. The first one is the Thinking Healthy Programme). It uses cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, to treat perinatal depression — depression that occurs during pregnancy or shortly afterwards in women. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been evaluated in numerous studies, mostly in clinical settings, and has been proven to be effective in different meta analyses as well.

For the Thinking Healthy Programme, community health care workers were trained to deliver CBT to depressed women. This was tested in a large RCT (randomized controlled trial) in Pakistan. The results here indicate quite clearly that women in the intervention group were much less likely to still suffer from major depression at follow-ups in six and 12 months, compared to the control group.

It is perhaps interesting to note that the Mental Health Innovation Network estimates that treating one woman via the Thinking Healthy Programme costs roughly $10. And, in case you were wondering, the control group had the same number of visits by community health care workers. The difference was just that these healthcare workers had not been trained to deliver CBT specifically.

The second programme that I would like to introduce is the Friendship Bench. It has been tested in Zimbabwe — also a low-resource setting. Its task-shifting approach is especially interesting. Task-shifting essentially means that specialized healthcare services are shifted from health care professionals to so-called “lay health workers.”

In this case, many health workers were trained to deliver structured problem-solving therapy. Through this task-shifting approach, it is possible to address the shortage of specialized health workers and to lower the cost of treatment.

Hopefully this has given you some sense of the different solutions that already exist.

The three reasons that I just presented motivated us to start MHPEP. Additionally, relatively little attention has been paid to mental health by the EA community. Therefore, it’s still unclear what the best mental health giving opportunities are. This is what we want to find out through MHPEP. And ultimately, we also want to compare these opportunities to those currently recommended, for example, by GiveWell.

Our research process so far

So what has our research process looked like thus far? It consists of three different rounds.

First, we have created a long list of programs targeting mental illness, and we've made a shadow assessment of their cost effectiveness.

As a second step, we narrowed down the number of programs to create a short list.

Third, we aim to carry out in-depth evaluations that will potentially result in a list of recommended donation opportunities. We’ve yet to do this.

Since we are currently in round two, I will focus on the first two [phases of our research].

Where did we start for round one? We began with a database: the Mental Health Innovation Network. Experts in the field of global mental health told us it was the most comprehensive database listing mental health programmes.

It currently lists 210. Since that is a lot, we decided to focus on programmes targeting depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. We did that because, as I mentioned earlier, depression and anxiety are responsible for a large share of the burden of disease caused by mental disorders. There's also evidence suggesting that they're quite bad for subjective well-being.

[That enabled us to reduce the list to] 70 programmes. Each was then assessed by three randomly assigned screeners using a pre-specified framework. This resulted in 25 programmes on our long list. If you're interested, you can find all of the details about this step in our EA Forum post.

In the second round, we assessed additional criteria. These included whether the programme had been tested in a low-resource setting (where, in general, we assumed costs to be lower) and whether there is an organization attempting to scale up the program (this isn't always the case). We also assessed the evidence base [to determine] whether there was at least one published direct controlled trial supporting the program's effectiveness.

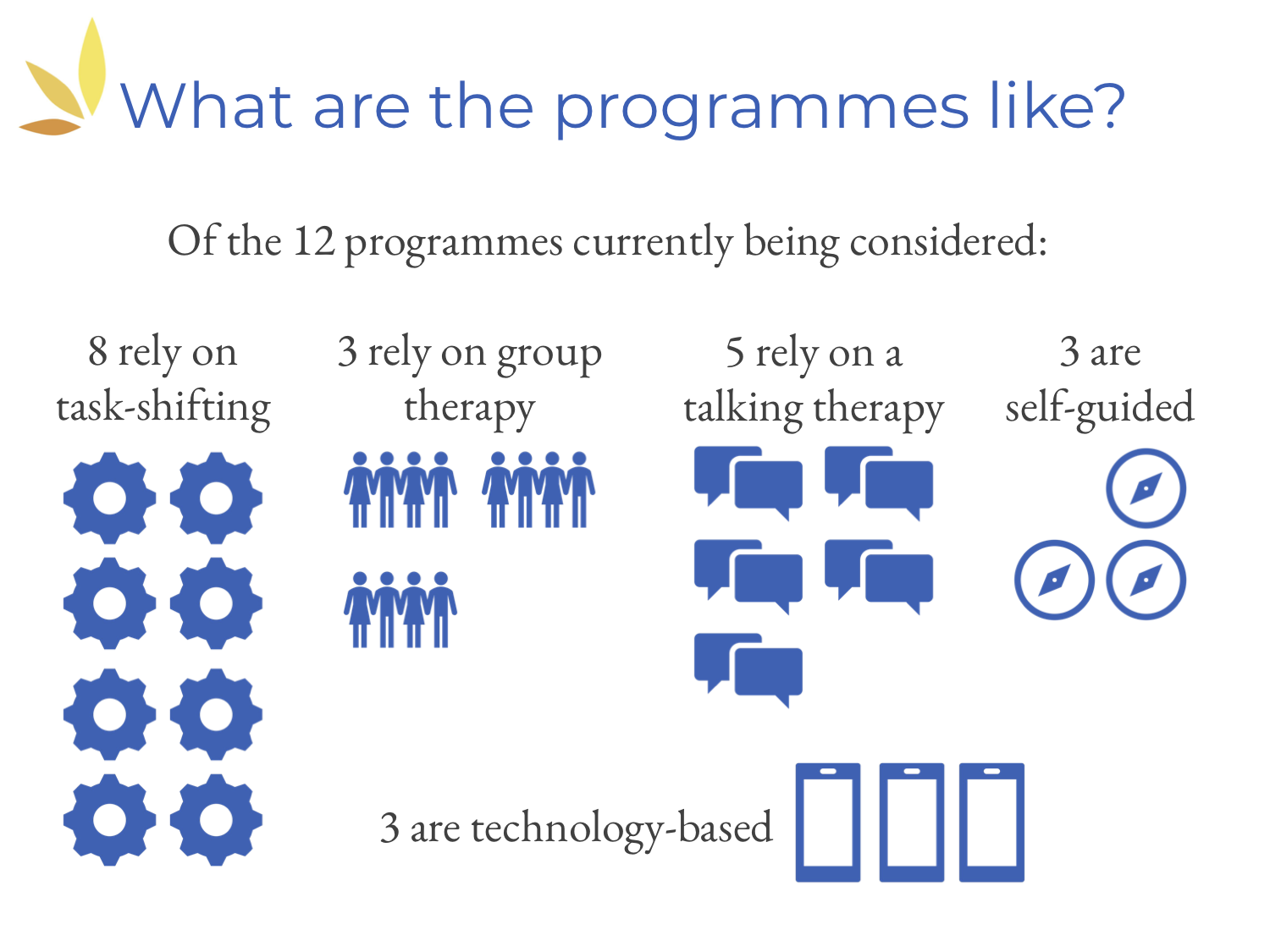

By doing that, we further narrowed down the number of programs to 12. Perhaps you're wondering what these programs are like.

We've created [the above] slide, which shows that more than half of the interventions rely on the task-shifting approach, almost half rely on some sort of talking therapy, a few rely on group therapy, a few are self-guided, and a few are technology-based (for example, they might use mobile solutions like apps).

I'd like to stress that this is not the final set of recommendations. We're still in round two, and plan to reach out to the organizations as a next step to carry out in-depth analysis. Then we’ll be able to make some recommendations.

Limitations and lessons learned

Before I conclude, I would like to share some limitations and lessons learned.

Our biggest limitation is probably that we used the Mental Health Innovation Network as a starting point. This database has not been systematically updated since 2015, which means that we may have missed out on quite a few programmes which have been established or set up more recently. Also, for many programmes, the information available on the network is quite limited. Therefore, especially in the first round — when we didn't have much time to assess each intervention completely — we may have excluded some potentially promising programmes.

Second, we have not considered any macro-level initiatives. The Mental Health Innovation Network lists mostly micro-level interventions, which are based on randomized controlled trials or other controlled trials. It does not contain many initiatives, for example, that aim for policy change at the macro level. For us, this has the advantage that in the future, we can compare our recommendations to GiveWell's, for example. But of course, it's possible that we have missed highly promising programs.

Next, I would like to share some lessons learned regarding the organization of a remote team of volunteers. Over the last one and a half years, it has been quite impressive how our team of volunteers — spread out across different countries and time zones — has been able to collaborate quite productively and effectively. On the other hand, I have to say that this requires good management, and that even though our progress has been quite steady, it has also been rather slow.

If you're interested in [learning more], we're very happy to share our experience. You can sign up for HLI's newsletter or send us an email. And we would, of course, very much appreciate your donations to HLI. Also, we're currently looking for summer interns; please take a look at our vacancies page.

In summary, there are three things I would really like you to take away from this talk:

1. Mental health is a large and tractable problem neglected inside and outside of the EA community.

2. Our team of remote volunteers are currently on the second of three research rounds to identify the most cost-effective mental health giving opportunities.

3. Our next steps involve collecting further information from [our short list of] programs, such as cost data, and conducting more detailed analysis.

[In the slide above,] you can find our references for further reading. I would like to thank you very much for your attention, and I look forward to your questions and some further discussion during the Q&A.

Bridget: Thanks so much for that talk, Jasper, and for joining us. I'm also delighted to welcome Clare Donaldson for this live Q&A section of the talk.

Clare joined the Happier Lives Institute as Chief Operating Officer after attending the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program. She has interned on the research team at Development Media International and helped lead EA Cambridge. She also has a PhD in geophysics from the University of Cambridge.

Thanks so much for joining us, Clare. I can see that we've had a number of questions submitted [by conference participants] already. [...] Let’s get started.

As Jasper mentioned, the Mental Health Programme Evaluation Project is just one of several projects being undertaken at Happier Lives Institute. Clare, could you perhaps give us a high-level overview of the Happier Lives Institute and the scope of work that you have going on at the moment?

Clare: Sure. We're researching the most effective methods for improving global well-being. Many of us here today are probably trying to maximize well-being. But often with impact evaluation it's common to use things like DALYs, QALYs [quality-adjusted life years], or income as metrics.

These are proxies. They’re really important, but probably not what we ultimately care about. What’s different about HLI is we're enthusiastic about subjective well-being (i.e., self-reported happiness and life satisfaction data). We think these data might be closer to what we really care about, and represent an exciting metric to use when determining how to do the most good.

Bridget: Jasper, what metrics are you using to try to quantify the impact of the different interventions and compare them?

Jasper: Thanks for the question. Essentially, we have to use the data that we have at hand at the moment when we're comparing different mental health interventions or programmes. We usually use the standard metrics — for example, the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 to measure the severity of two depressive symptoms, or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 scale, which is used to gauge anxiety.

As I said during the talk, we ultimately aim to compare these programmes with other organizations’ recommendations, such as GiveWell’s. That means, of course, using subjective well-being data.

Bridget: I guess that feeds into HLI’s broader work, which Clare mentioned. On subjective well-being, one question from [the audience] is whether you favor a life satisfaction measure over measures of affect or momentary happiness.

Clare: We think that the exciting leap is moving away from these objective measures to subjective measures. Life satisfaction is much easier to measure; it can be measured with one question or just a few questions, and you can just do a survey quite easily. Therefore, there's a lot more life satisfaction data out there than data on affect or happiness. For that reason, I think it's quite likely that we were much more likely to use life satisfaction as a measure.

It's an ongoing question for us at HLI — a debate of whether we could obtain the happiness data which we would like to use. But as I said earlier, I think any subjective measure is a great step, and broadly speaking, these lifestyle and happiness data seem to go together, at least [for our purposes].

Bridget: It sounds as if there are some projects and programmes that are aiming to create life satisfaction measures. Are there similar measures that you know of for affect? [That is, in the sense of “positive affect.”]

Clare: You mean within research [organizations] and academia?

Bridget: Yes.

Clare: I’m not sure. Something else I’ll mention is that I think economists are, in general, probably more excited about life satisfaction. I think that's closer to utility. But a lot of people within effective altruism identify with hedonism, which is caring about happiness in the moment. It's something we should think about at HLI; one impact we could have is encouraging researchers to collect more of this data.

For example, asking subjectivity questions could be quite simple if you were already doing an RCT somewhere; it's not that much extra work to add in questions. We need to keep working on making that happen and offering good solutions to [encourage] researchers to add [questions and create] an extra data set that we could access.

Bridget: Yes, there's certainly a lot of work to be done. Jumping into a different question from the [audience], which I’ll direct to Jasper: How do mental health issues differ cross-culturally, and how do you handle that issue?

Jasper: I think that's a really important question. In general, I think it's fair to assume that our understanding of mental health varies quite significantly in different contexts. Any RCTs or scale-ups need to be adapted to the context in which the work is conducted.

For example, I spent some time last year in India working with Sangath, which is an NGO, and they're doing exactly that: testing interventions for scale-up. One of my main takeaways was that anything you use to measure outcomes, whether it’s a questionnaire or something else, needs to be tested first — usually through qualitative research — within the specific context in which you’re working. Only then does it make sense to talk about mental health.

What we definitely cannot, and should not, do is take a one-size-fits-all approach and [apply it across] very different contexts.

Bridget: Here’s another question for Jasper (and Clare, feel free to jump in at any time): What proportion of mental health problems in low-income countries, and perhaps even broadly speaking, do you think can be solved or improved through non-mental health interventions?

The example the questioner provides is that preventing domestic violence [helps improve mental health]. I think this also links to another question [from the audience], which is about the relationship between mental health and physical health. What are the impacts of improving physical health through mental health, and vice versa?

Jasper: Again, that’s a really interesting and important question. You might be familiar with the causal concepts that are mainly used in epidemiology. Different causal aspects come together [and collectively cause] a disease or disorder to occur.

This certainly applies to mental disorders as well. There are so many causes to take into account that it's hard to provide a number; I don't think I could do that off the top of my head. But in general, I think there's probably a considerable proportion that could be prevented through non-mental health programmes or interventions.

Domestic violence is an especially [relevant example] that has received more attention recently. Of course, it's very closely intertwined with any mental health discussion.

Bridget: Yes. Clare, is there anything you want to add?

Clare: As Jasper said, it's hard to pick a number off the top of your head. It reminds me of [Jasper’s earlier point] that with mental disorders, no deaths are included in the figure [indicating] the global burden of disease. There's nothing there, and that's partly because it's really hard to tease apart comorbidities from different diseases.

If someone dies from a heart attack, their depression may have played into that. But it's methodologically tricky [to prove]. I think that the people [researching] the global burden of disease are working on that.

Another interesting part of this question is the relationship between mental health and poverty. An easily readable analysis has just come out by Ridley, [Rao, Schilbach, and Patel]. It looks at the causal effects from both [directions]: how mental health affects income, and also how money, like a cash transfer, acts on mental health. These things go both ways, and teasing apart that relationship is difficult. RCTs are a helpful tool.

Bridget: Great. Clare, could you give some advice to the people who are running [research on] the global burden of disease that would help quantify and represent the impact of mental health disorders? That's a hard question.

Clare: Let's talk about that question. I'm flattered that you think I know the answer. I suppose the only thing I would say is that it's done in DALYs, but DALYs only capture one aspect of mental health. You can only have an impact on DALYs if you have a disorder like depression. So if you're suboptimally happy, but you don't necessarily have depression, that's not accounted for in the global burden of disease at all. We're missing a huge aspect of what makes life go well for people by only relying on one part of [mental health].

Bridget: Yes. Unless they've made recent updates, my understanding is that the disability weights come from asking people whether they think a certain set of symptoms is healthy relative to another. And I think that the use of the word “healthy” can be difficult, because there might be some things that we think are important from a health perspective, but we wouldn't necessarily think that people with that disorder are unhealthy.

Clare: Yes, exactly.

Bridget: Okay, another question from [the audience] is about the use of psychedelic medicines like psilocybin to alleviate mental disorders. It is something that’s frequently discussed in mental health, and there's a lot of excitement surrounding it. What do you think of it? Should we be investigating this more, or do you have an update on the research in that space?

Clare: I don't have an update on the research. My understanding is that there are some exciting initial results on using psychedelics for the treatment of things like PTSD. There are big trials underway, and personally I'm waiting for those results to see if psychedelics come through when we test them at scale.

Bridget: Another question: Why do you think mental health interventions might've been neglected in the EA space previously?

Jasper: I think the EA community over the last year has, at least in terms of global health, mostly relied on the conventional metrics that we've touched on already: DALYs and QALYs [quality-adjusted life years]. I don't know if any listeners have seen the Founders Pledge report, for example, estimating the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds, which is one mental health program we're looking at. They're still using the standard framework.

Through that lens, it could be argued that mental health interventions [generally] seem less cost-effective than, say, the classic bednet intervention that AMF [Against Malaria Foundation] uses. I think that might be one of the reasons. But it's also fair to say that the topic [of mental health] has been neglected not only within the EA community, but globally over the last several decades. It has received more attention lately because of the ongoing public debate about it.

Clare: I think you're completely right, Jasper. Many of the academics I've spoken to have reflected on [the fact that] it’s only over the last decade or two that we've started to pay attention to mental health. It seems like it's been neglected more generally.

That makes me excited about it as a cause area. Global mental health seems like a younger field than global physical health. And I'm sort of hopeful that if we start new projects now, we can steer [global mental health] in a way that aligns with effective altruism.

Bridget: That’s a really good point. Being a younger field might make it a bit easier to steer it in a certain direction.

Clare: Potentially, yes.

Bridget: That’s related to the next question: What can an individual or small group do to help work on this? Do you have any advice or suggestions? I'll go to Jasper first.

Jasper: I'm afraid I don’t have any concrete recommendations off the top of my head. But I would generally recommend trying to talk to as many people in the global mental health field as you can. Listen to what they’ve found to be the most pressing issues to work on based on their years of experience in the field.

I know that's very general advice. Clare, maybe you have something more specific to add.

Clare: A wonderful thing about the effective altruism community is [that you can connect with others and launch projects together]. A group of people met at EA Global in London. They wanted to do something, they got together, and they've just done it and carried on doing it today. So I think if you're listening to this you can do that too — connect on Slack with people at this conference.

There's a mental health and happiness Facebook group you can join, among other ways. And I think it is possible to do some impactful research. This isn’t specific advice, but I would really encourage people to try and find something like that.

Bridget: Yes, being aware of what's going on and also reaching out and making connections.

Clare: Yes, of course. And do email us. We’d love to hear from you.

Bridget: And I believe on one of your last slides, Jasper, you mentioned that HLI was looking for summer research interns. Maybe that could be something that people could apply for as well if they're interested in getting more involved.

Clare: Thanks for reminding us. That’s one thing I should have said.

Bridget: No worries. So we are getting toward the end of our Q&A session. As wrap up, I'll give you both the opportunity to communicate anything else you’d like. And also, Clare, if you could perhaps give us an idea of the goals for HLI in the next 12 months and where you see the organization heading. Over to you first, Jasper, and then we’ll finish up with Clare.

Jasper: I guess I just want to say thank you very much for listening, for caring, and for wanting to know more. Once again, I'd like to stress that we have an EA Forum post if you're keen to learn more about the MHPEP. Otherwise, feel free to reach out anytime. We're very happy to chat and connect.

Clare: I suppose I'll tell you a little bit more about the other projects we're doing. I think our research agenda is fairly broad. It's a mixture of theoretical and applied research. The MHPEP is at the applied end [of the spectrum]. But we touched on theoretical work earlier [when discussing] which measure of well-being to use.

We're working on that and the theory behind that thinking. We’re looking at validity and reliability — these kinds of practical questions. And perhaps our main research project this year straddles those two things. We're exploring different interventions and trying to assess the impact in terms of subjective well-being. We're trying to actually do them and see how they work in practice. We started by looking at cash transfers and then we [investigated] some physical and mental health interventions.

What we're really interested in is how our priorities might change when we use this metric. Does it bring up new things we haven’t realized? And on the practical side of things, how much data is there? What are the bottlenecks that come with subjective well-being impact evaluation? I hope in the next year that we have some answers to steer our research in the future.

I think HLI’s path is somewhat uncertain. Which way are we going to go on this theoretical-to-applied spectrum? We're trying to take a scientific approach, test out different things, and learn. And hopefully we'll find the path of highest counterfactual impact in the long run — and we'll make lives happier along the way. That’s the goal that we're all trying to remember.

Bridget: And it does sound like a pretty good goal. Thanks so much for joining us here. And thanks also for the work you're doing with HLI. It's been great to learn a little bit more about it and to hear from you both.