Moral Theories Lack Confidence

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-05-30T20:25 (+14)

This is a linkpost to https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/moral-theories-lack-confidence

Be careful how you personify them

It can be convenient to personify moral theories, attributing to them the attitudes that would be fitting if the theory in question were true: “(Token-monistic) utilitarianism treats individuals as fungible mere means to promoting the aggregate good.” “Kantianism cares more about avoiding white lies than about saving the life that’s under threat from the murderer at the door.”

If a theory has false implications about what attitudes of care or concern are actually morally fitting, then the theory is false. That’s how fittingness objections to moral theories work, and I think such objections are perfectly legitimate in principle. The main challenge to making such objections stick is just that critics are often mistaken about a theory’s implications for fitting attitudes. (Follow the above links for details.)

Such reasoning is especially dubious when it comes to doxastic attitudes, like judging a verdict to be “obvious”. Not only do moral theories literally lack doxastic attitudes, you can’t read off from them conclusions about what we—as believers in the theory—ought to find obvious. The simple reason for this is that no moral theory can tell us how confident we ought to be in the theory itself.

Why this matters

Sometimes confused people object to utilitarianism for making “confident” claims about deeply unclear or uncertain matters. (The most famous such confused person was Bernard Williams.)[1] Harvard philosopher Jimmy Doyle once endorsed the following argument:

Utilitarianism says it’s clear that Jim should kill the Indian; it’s not clear that Jim should kill the Indian; therefore utilitarianism is false.

But utilitarianism doesn’t say anything about what is “clear”. It may clearly entail that Jim should kill the Indian, but being clearly entailed by a theory—even a true theory!—doesn’t mean that a proposition is clearly true. After all, perhaps we ought to give some credence to (reasonable albeit mistaken) rival theories that yield different verdicts.

Simply put: The logic of ‘obviousness’ is such that you cannot reason from the truth of a theory U, and the fact that a verdict V is obviously implied by U, to the conclusion that V itself is obvious:

U, Obv(U→V), ∴ Obv(V) ❌

The obviousness of a conclusion follows only if every premise is obvious:[2]

Obv(U), Obv(U→V), ∴ Obv(V) ✅

But utilitarianism does not claim to be obvious. It could be non-obviously true. So we should not expect its controversial verdicts to be obvious, even if they follow straightforwardly from the truth of the theory—that is, even if Obv(U→V).

People, not theories, should be uncertain

You may think the critics have an easy fix at this point: simply switch to instead talk about what believers in the theory—utilitarians, rather than utilitarianism—will find obvious. But again, these attributions falsely assume that utilitarians must have perfect confidence in their theory. More plausibly, everyone ought to split their credence across a range of different theories.[3] We should, in short, be morally uncertain.

This relates to my old refrain that it’s no virtue of non-utilitarian theories that they remain silent on all the toughest questions in decision theory and population ethics.

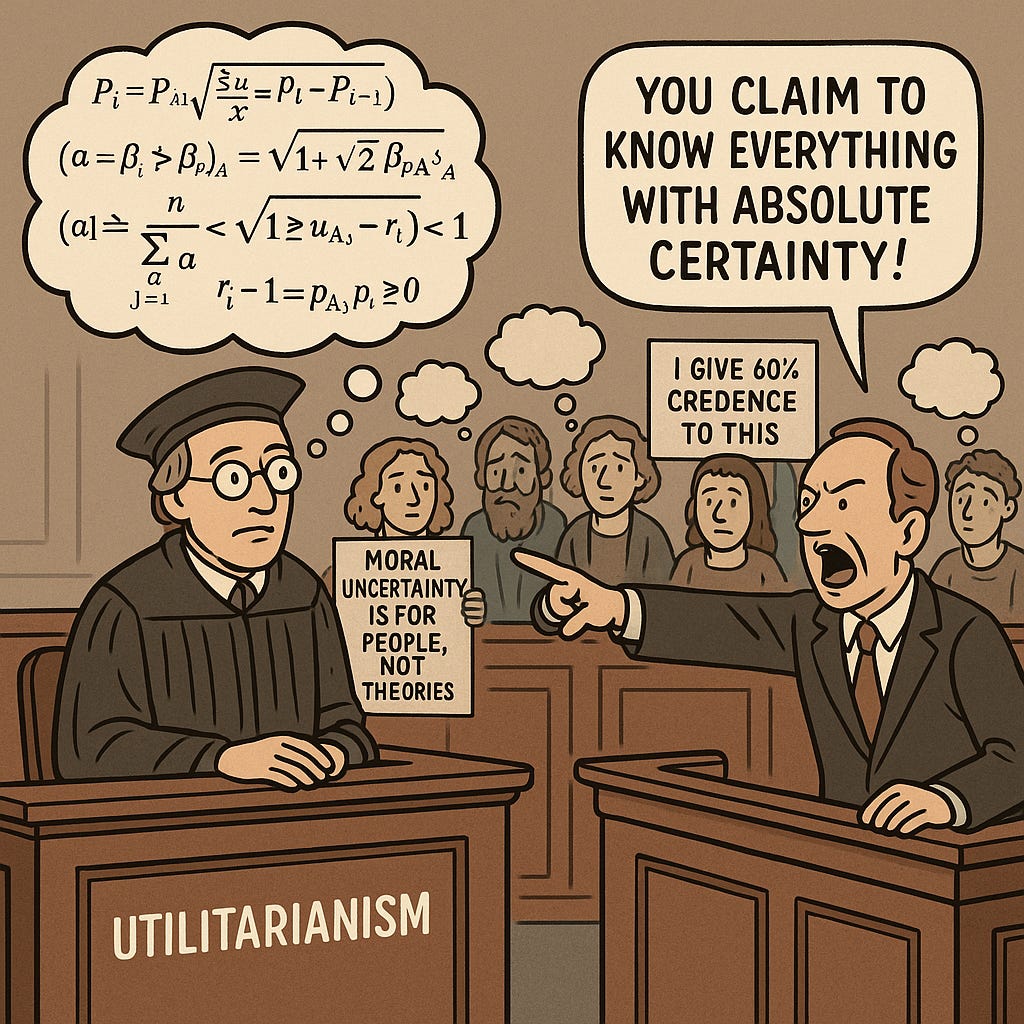

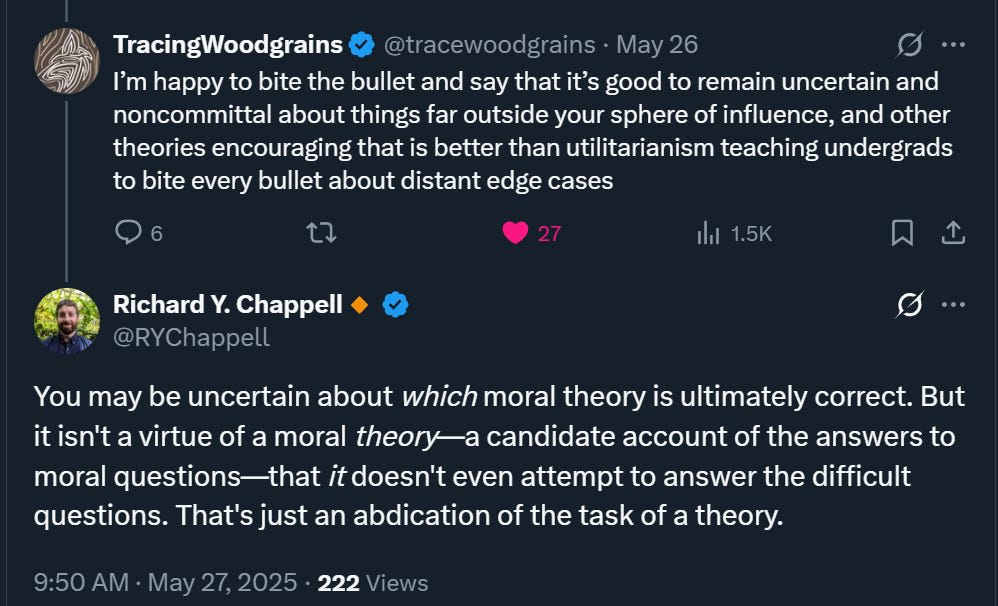

TracingWoodgrains recently offered the interesting response that “it’s good to remain uncertain and noncommittal,” and so “other theories encouraging that is better than utilitarianism teaching undergrads to bite every bullet…”

You can see my response: uncertainty is for people, not theories.[4] But perhaps we can add this to my list of paired mistakes forming protective equilibria: Really, you should never fully commit to any one moral theory, and the theories themselves should aim to comprehensively answer (all) moral questions. But if you fail on the first point and are psychologically disposed to go all-in on whatever you “believe” (rather than sensibly spreading your credence around), then you may do best to also accept an incomplete and non-committal theory!

(I see this as closely related to the #4 pair: “Using deontology as a fudge to compensate for irrational naive instrumentalism.”)

Conclusion

Trace may be right that undergrads are poorly taught in moral philosophy classes. But I differ in where I lay the blame. Insofar as there’s a problem with how undergrads engage with utilitarianism, it stems not from anything intrinsic to the theory, but the misguided background assumptions of all-in belief and naive instrumentalism that too many people—students and professors alike—bring uncritically into the classroom, and never pause to question.

- ^

In his “Jim and the Indians” case, Williams objected, not that utilitarianism necessarily yields the wrong verdict, but that it “regards” its verdict as “obviously the right answer”.

- ^

There may be additional requirements beyond this, e.g. that the inference rule is also obvious (which in this case, it is).

- ^

Though people may differ in their judgments about which theories warrant non-trivial credence. (I don’t personally give any non-trivial credence to deontology. But I do grant a lot of weight to moderate departures from utilitarianism—e.g. partiality and desert-adjustments—and I give some weight to some quite radical departures.)

- ^

As an independent point, I also think people are often overconfident in their claims about how uncertain others ought to be. Much depends on the merits of the case, after all, which cannot easily be judged in advance of inquiry.