How to Think about Collective Impact

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-08-25T17:00 (+11)

This is a linkpost to https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/how-to-think-about-collective-impact

Universalizability Done Right

When thinking about big social problems like climate change or factory farming, there are two especially common failure modes worth avoiding:

- Neglecting small numbers that incrementally contribute to significant aggregate harms. (The rounding to zero fallacy)

- Catastrophizing any actions that contribute (however trivially or justifiably) to significant aggregate harms. (The total cost fallacy)

These two mistakes are at opposite ends of the spectrum, and you can see how striving to avoid one might make you more susceptible to the other. The general challenge is that people struggle to determine which morally-mixed actions—acts that provide some benefit to the agent at some collective cost—are or are not worth the negative externalities.

The Ideal Solution: Economic Policy

It would be ideal to relieve consumers of the moral burden by internalizing the negative externalities into the cost of consumption, e.g. via carbon taxes and such. It’s really bizarre to me that this is not more popular. If you oppose such Pigouvian taxes, you’re effectively saying, “I want to be able to impose costs on others for the sake of a lesser benefit to myself,” which seems blatantly unreasonable. I guess most people just aren’t that committed to being even minimally reasonable (or avoiding egregious selfishness, so long as it’s normal), which is a depressing thing to realize. But for those of us who actually want to make reasonable tradeoffs, it would obviously help if the true costs were reflected in the price, so we could simply judge whether or not the price was personally worth paying in any given case.

Individual Estimates in a Bad Policy Environment

Given that we don’t have such helpfully informative policies instituted, we’re left having to guess at how the social costs of our actions compare to the personal benefits. Since calculation is hard, many instead resort to the lousy heuristics mentioned in our introduction—either rounding to zero or focusing on the total cost—to get an indiscriminate verdict that your action is either clearly fine or clearly problematic. The first thing I want to draw attention to is that such indiscriminacy is surely wrongheaded. It’s just not true that all actions that contribute to collective harms—e.g. by using energy—are normatively the same (either all worth it, or all not). Some but not all such actions are worth the costs![1] The answer isn’t fixed in advance, so if your moral thinking doesn’t yield this situation-sensitive verdict, you’re not thinking right.

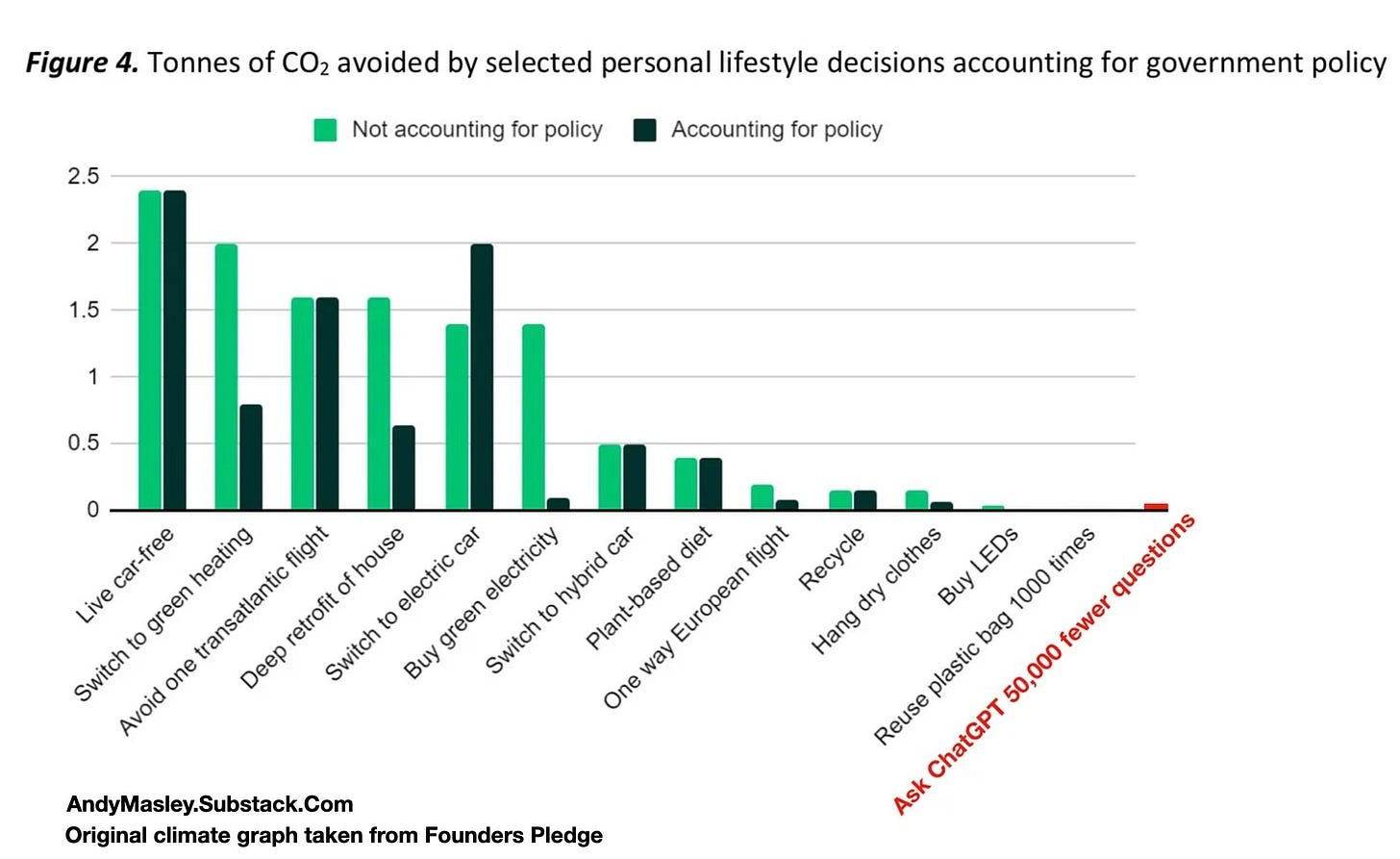

What we really need is a rough sense of the net (expected) value of our actions. As Andy Masley writes, “When making cuts for the climate, always consider the value you’re getting per unit energy, not just the total energy used.” You presumably have a sense of the personal benefits at stake; the trickier question is how to assess the social costs. For climate concerns, a useful heuristic is to just imagine that electricity prices were 50% higher:[2] probably anything electronic you find worth doing at current prices would still be worthwhile for you after that price increase. Personal consumption of electricity generally seems incredibly low-cost relative to the benefits we get from it. As far as personal resource consumption is concerned, my sense is that our focus should instead be on reducing gasoline usage:

(Though I think almost all personal consumption choices are trivial compared to the question of how much we donate and where. John Broome argues that even very cheap carbon offsets do vastly less good per dollar than the most effective charities, for example. So, on present margins, it would seem a mistake to prioritize making any significant sacrifices for the climate when you could instead focus on improving the quantity and quality of your donations. If Broome is right, a measly ten cents to a GiveWell top charity may do more good for people[3] than would reducing your carbon footprint by a full tonne.)

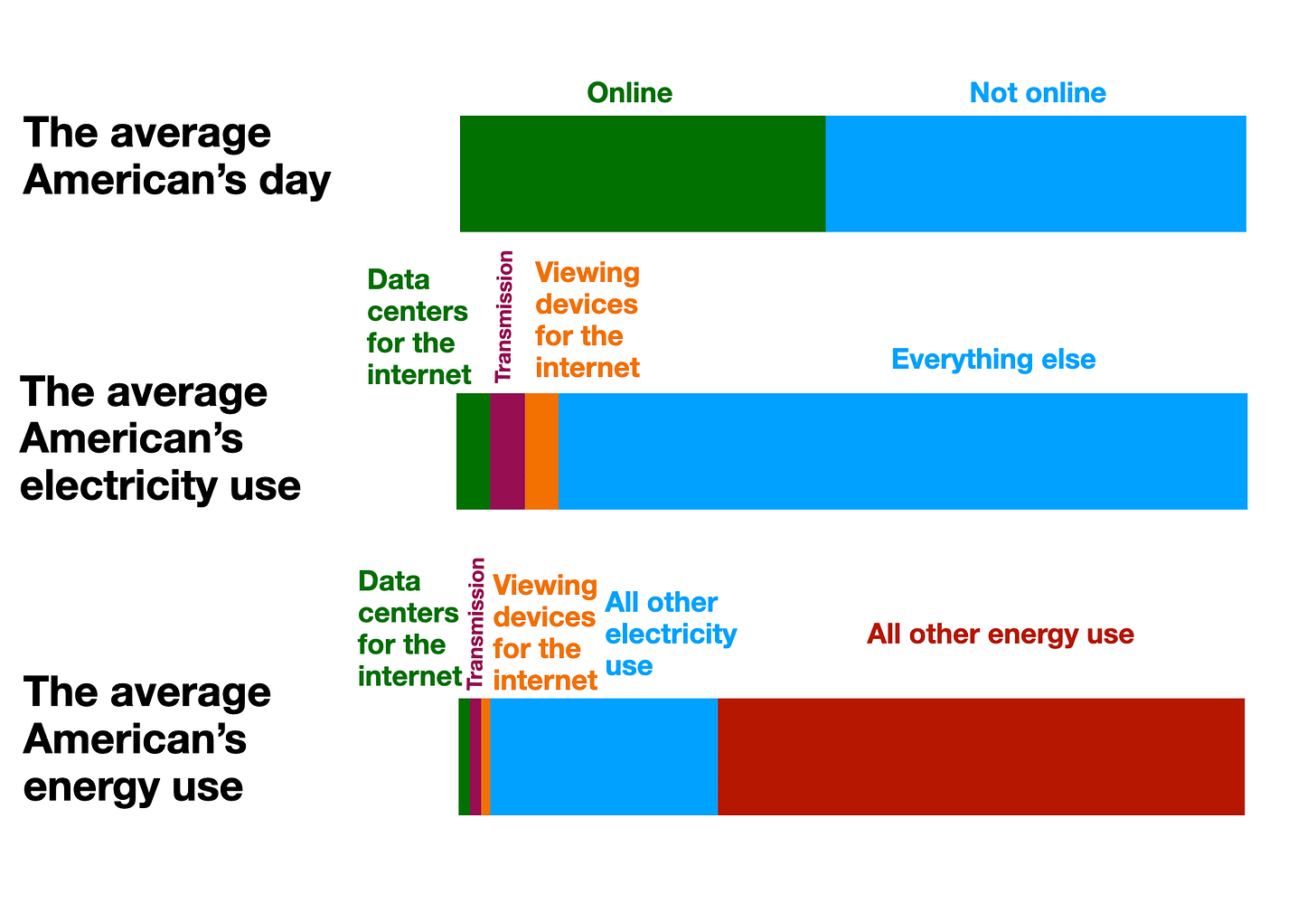

A helpful heuristic is to look at your overall energy usage, and consider which cuts would be most “cost-effective” for you. It would be crazy to make significant personal sacrifices for a 0.01% reduction of your daily energy budget, for example, if there were alternative lifestyle changes you could make that you would find less personally costly and that would also do orders of magnitude more good. In relation to that point, I appreciated Andy Masley’s observation that computing is efficient:

I’ve seen a lot of articles about AI include vaguely ominous language about how data centers already use 4% of America’s electricity grid, and might grow to 6%… I think the authors should consider adding “It’s a miracle that this is only projected to climb to 6% given that Americans spend half their waking lives using the services data centers provide. How efficient! Also, 6% of our electricity budget is only 2% of our total energy use.”

In short: read Andy Masley. He has assembled so much helpful info for putting our energy use in perspective.

What about Universalizability?

A new tool is needed if you don’t trust the standard “social price of carbon” estimates, and also don’t merely want to work out which lifestyle changes should be prioritized but more broadly want to know which forms of energy use are truly worthwhile at the end of the day (since it’s at least possible that almost all of our energy use turns out to be unjustified—though I don’t personally believe that). That’s where a kind of universalizability comes in: if everyone used energy like we personally do, would the total benefits outweigh the costs? By considering the total harms of carbon emissions, and then dividing the costs proportionately across incremental contributions, we may get a better sense of the average social cost of (a fixed unit of) carbon emissions, in order to balance this against the personal benefits we—and others—get from energy consumption.

“What if everyone did that?” is widely considered to be an illuminating moral question. But if not interpreted carefully, it can lead to absurd conclusions, like that it’s immoral to pursue any career outside of the food sector (since if everyone did that, we’d all starve to death). As this example shows, it’s important to properly determine the scope of the “that” that you’re universalizing. A couple of tips for avoiding absurdity:

- Consider the most abstract decision procedure that yields the action in question, and test whether that underlying cognitive process—e.g., to pursue the career you want (all things considered, including changing market prices, and without violating anyone else’s rights, etc.)—rather than its contingent output in your specific case, is universalizable. Note that it seems to work fine to let people choose from among legitimate careers in response to market signals and personal preference: we get all the food we need that way. So pursuing a personally desired (and otherwise legitimate)[4] career turns out to be perfectly universalizable after all.

- Since different people have different starting preferences, it can make more sense to ask “what if everyone felt free to do that?” rather than “what if everyone did that?” The results are similar to those obtained via abstraction, but it may be a simpler heuristic to follow.

When applied to resource use, naive invocations of “what if everyone did that?” reasoning can easily fall into the total cost fallacy. Two key remedies to bear in mind:

- Consider total benefits as well as total costs. This can be difficult because the people who make these arguments often aren’t the ones experiencing much personal benefit from the targeted activity. People vary, and it’s dangerously easy to demand that other people stop doing things that you personally don’t get much value from. To ward against this error, I think it’s really important to inculcate a strong default disposition of respect for others’ preferences: if they’re willing to pay money for something, and report finding it worthwhile, you should be very wary of overriding their verdicts about the personal value they get from events in their own life.

- Secondly, take care once again to delineate the scope of “that” as charitably as possible. Many categories (including “energy use”, “datacenter use”, and “AI use”) clump together many relevantly different subcategories—some of which may be more or less costly, and less or more valuable, than others. As I previously wrote: “ignoring relevant differences and treating everything in a broad category as taboo is a sign of lazy ideological thinking.”

Putting these two points together, merely feeling like “I would prefer a world in which nobody used AI over the current state of the world” (which I understand that many people—especially academics in my social circles—feel) is not a sufficient justification for judging that all AI use is unjustified or fails universalizability tests.

A key thing to bear in mind is that many uses (including the ones you’re likely most worried about) are going to happen whether we like it or not. When academics chat to each other on social media about AI, for example, it simply is not within their power to convince companies to stop using AI for personalized marketing, corporate administration, or whatever else is gobbling up most of the datacenter use. Consumer chatbot use is (I gather) fairly minor by comparison. And even there, the people we can most easily influence may be among those who are already least likely to misuse the technology.

As outlined in How to Save the World, a key insight from moral philosophy (Donald Regan’s co-operative utilitarianism in particular) is the need to distinguish cooperators from independent agents when trying to come up with a good plan of action. The best plan in the world may be worse than useless if others aren’t willing to play their parts in it. You need to make a plan that works well given who is actually willing to cooperate, and given the reality of what’s beyond your control (including the actions of independent, non-cooperating agents).

Applied to our present case, I see no good reason to ask academics and other high-functioning professionals to boycott AI (if they would otherwise find good uses for it) just because some uses by other groups (some companies, cheating students, etc.) are bad. Any suitably charitable form of universalization, as applied to a decent use of AI, will simply ask about universalizing such decent uses of AI, which is surely net-positive. (Imagine if the technology was only ever used responsibly and well!) When critics, refusing to decouple the good and bad uses of a product, urge responsible users to boycott it, this is both (i) a misuse of universalizability reasoning, and (ii) likely to have negative actual effects (due to reducing good use while having no effect on bad use).

Could you change wider social norms?

The best case for boycotts may instead rest on a kind of political hope, rather than on rigorous universalizability reasoning. I assumed above that our moralizing makes no difference to those outside of our social circles. But one might take this assumption to be too pessimistic, and rather hold that the history of social change shows that we (sometimes) can change society-wide norms by taking a strong stand.

It’s ultimately an empirical question, for any given issue, how feasible it would be to institute a society-wide taboo or otherwise radically change prevailing norms. Philosophically, I guess the main thing I’d want to insist on is just that you give some thought to trying to assess whether the attempt is best regarded as positive or negative in expectation (and, ideally, whether it is more positive than other options available to you). You need some degree of sensitivity to probabilities and stakes if you want your moral efforts to have a non-random expectational valence (and hence be truly justified and responsible) rather than just playing moral roulette.[5]

- ^

Further: there are a lot of actions in both categories, so it’s not like a blanket verdict will serve as a “close enough” approximation. We really need to distinguish reasonable vs wasteful resource use, in practice as well as theory.

- ^

Claude Opus 4.1 and GPT-5 Thinking converged on this as a reasonable estimate of how much electricity prices would rise on average in response to a carbon tax internalizing the full social price of carbon. Feel free to correct this if you have a more reliable source.

- ^

Taking wild animal interests into account may change this specific verdict, but doesn’t affect the general point that well-targeted donations are a much bigger deal than one’s personal carbon footprint. It just changes one’s preferred “target” charity.

- ^

One might try to pin down the content of “legitimate” here by considering which careers it would be best to have generally regarded as morally illegitimate. (Perhaps just any that predictably cause more social harm than good?)

- ^

I think there’s something fundamentally unserious about the sort of moral philosopher who endorses the cluelessness objection to consequentialism and yet is deeply committed to activism—which, by their own lights, they have no reason to think does more good than harm. (Compare my response to Srinivasan’s question about “how would we go about quantifying the consequences of radically reorganizing society?” Seems like you need an answer before you can know whether “radically reorganizing society” is a good idea or not!) See also:

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-26T19:42 (+2)

Executive summary: This exploratory post argues that when assessing morally mixed actions—like personal energy use or AI adoption—we should avoid both trivializing small harms and catastrophizing them, instead using tools like Pigouvian taxes, rough cost–benefit heuristics, and carefully framed universalizability tests to distinguish reasonable from wasteful resource use.

Key points:

- Two common mistakes in thinking about collective harms are the rounding to zero fallacy (ignoring small contributions) and the total cost fallacy (treating all contributions as equally catastrophic).

- The ideal solution is to internalize externalities through policies like carbon taxes, which would make tradeoffs transparent and remove the moral burden from individuals.

- In the absence of such policies, individuals should estimate the expected net value of their actions, focusing on cost-effective reductions (e.g., gasoline use over electricity) and remembering that donations to highly effective charities typically outweigh lifestyle sacrifices.

- Universalizability reasoning (“what if everyone did that?”) can help but must be applied carefully: one should abstract to decision procedures, respect others’ preferences, and distinguish between subcategories of resource use to avoid absurd or overly broad conclusions.

- Boycotts of technologies like AI, when motivated by indiscriminate universalization, risk suppressing good uses without affecting bad ones; a more sensible approach is to encourage and model responsible use.

- Shifting social norms through moral stands is possible, but its effectiveness is empirical; activists should assess probabilities and stakes rather than acting on hope alone.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.