How hard to achieve is eutopia?

By William_MacAskill, finm, Forethought @ 2025-08-06T17:43 (+56)

This is a summary of the new paper “No Easy Eutopia”, here.

How easy is it to get to a future that’s pretty close to ideal?

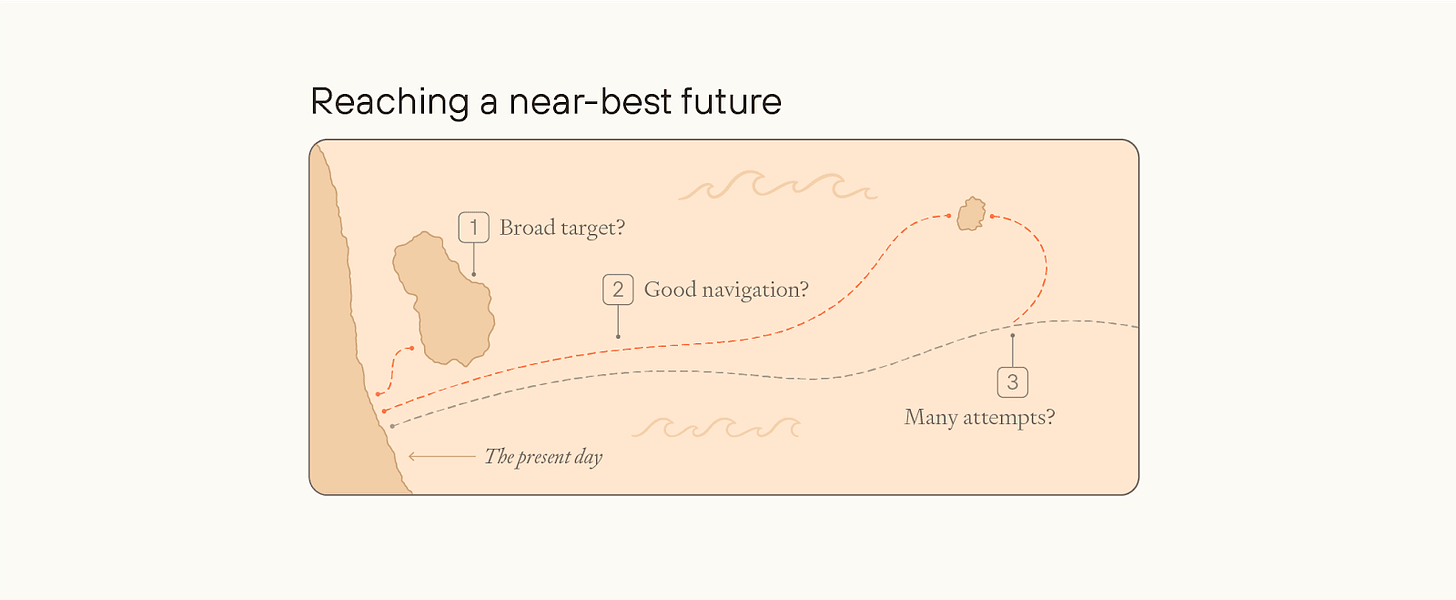

You could think of reaching eutopia as like an expedition to sail to an uninhabited island. The expedition is more likely to reach the island to the extent that:

- The island is bigger, more visible, and closer to the point of departure;

- The ship’s navigation systems work well, and are aimed toward the island;

- The ship’s crew can send out smaller reconnaissance boats, and not everyone onboard the ship needs to reach the island for the expedition to succeed.

Similarly, we could be on track for a near-best future for a few different reasons.

First, eutopian futures could present a big target: that is, society would end up reaching a near-best outcome across a wide variety of possible futures, even without deliberately and successfully honing in on a very specific conception of an extremely good future. We call this the easy eutopia view.

Second, even if the target is narrow, society might nonetheless hone in on that target — maybe because, first, society as a whole accurately converges onto the right moral view and is motivated to act on it, or, second, some people have the right view and compromise between them and the rest of society is sufficient to get us the rest of the way.

In No Easy Eutopia, we focus on the first of these. (The next essay, Convergence and Compromise, will focus on the next two.) We argue there are many ways in which future society could miss out on most value, or even end up dystopian - many of which are quite subtle. The “target” of a near-best future is very narrow: very unlikely to happen by default, without some beings in the future trying hard to figure out what’s best, and actively trying to make the world as good as possible, whatever “goodness” consists of.

You might think that it’s obvious that getting to eutopia is really hard. But we think this is not at all obvious. As we define quantities of value, we say that X future is twice as good as Y future just in case a 50–50 gamble between X and extinction in a few hundred years is as good as a guarantee of Y.

And now consider a “common-sense utopia”:

Common-sense utopia: Future society consists of a hundred billion people at any time, living on Earth or beyond if they choose, all wonderfully happy. They are free to do almost anything they want as long as they don’t harm others, and free from unnecessary suffering. People can choose from a diverse range of groups and cultures to associate with. Scientific understanding and technological progress move ahead, without endangering the world. Collaboration and bargaining replace war and conflict. Environmental destruction is stopped and reversed; Earth is an untrammelled natural paradise. There is minimal suffering among nonhuman animals and non-biological beings.

Suppose we could either get the common-sense utopia for sure, or a 10% chance of a truly best-case future and a 90% chance of extinction in a few hundred years. Our intuitive moral judgments, at least, are strongly in favour of taking the common-sense utopia.

But, ultimately, we think that intuitive moral judgment is mistaken. Here are two different arguments for that.

Future moral catastrophe

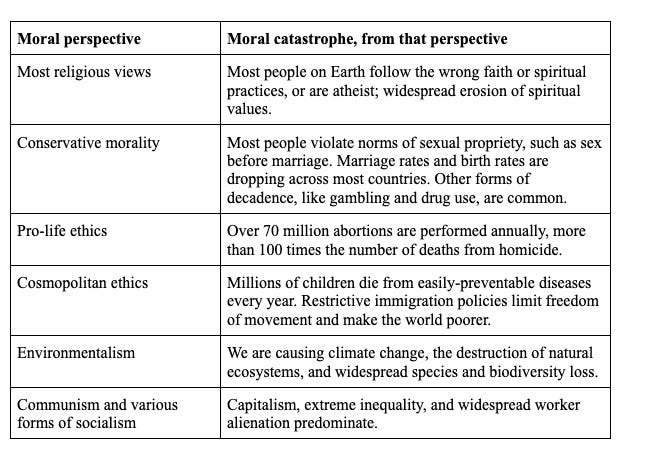

Today, we live in the midst of a moral catastrophe.

Technological and material abundance has given us the opportunity to create a truly flourishing world, and we have utterly squandered that opportunity.

Consider our impact on farmed animals alone: every year, tens of billions of factory-farmed animals live lives of misery. The suffering directly caused by animal farming may well be enough to outweigh most or all of the gains to human wellbeing we have seen. For this reason alone, the world today may be no better overall than it was centuries ago

Maybe you don’t care about animal welfare. But then just think about extreme poverty, inequality, war, consumerism, or global restriction on freedoms. These all mean that the world falls far short of how good it could be.

In fact, we think most moral perspectives should regard the world today as involving a catastrophic loss of value compared to what we could have created.

That’s today. But maybe the future will be very different? After superintelligence, we’ll have material and cognitive abundance, so everyone will be extremely rich and well-informed, and that’ll enable everyone to get most of what they want - and isn’t that enough?

We think not. We think there are many subtle ways in which the world could lose out on much of the value it could achieve.

Consider population ethics alone. Does an ideal future society have a small population with very high per-person wellbeing, or a very large population with lower per-person wellbeing? Do lives that have positive but low wellbeing make the world better, overall?

Population ethics is notoriously hard - in fact, there are “impossibility theorems” showing that no theory of population ethics can satisfy all of a number of obvious-seeming ethical axioms.

And different views will result in radically different visions of a near-best future. On the total view, the ideal future might involve vast numbers of beings each of comparatively lower welfare; a small population of high-welfare lives would miss out on almost all value. But on critical-level or variable-value views, the opposite could be true.

If future society gets its population ethics wrong (either because of misguided values, or because it just doesn’t care about population ethics either way), then it’s easy for it to lose out on almost all potential value.

And that’s just one way in which society could mess things up. Consider, also, mistakes future people could make around:

- Attitudes to digital beings

- Attitudes to the nature of wellbeing

- Allocation of space resources

- Happiness/suffering tradeoffs

- Banned goods

- Similarity/diversity tradeoffs

- Equality or inequality

- Discount rates

- Decision theory

- Views on the simulation

- Views on infinite value

- Reflective processes

For most of these issues, there is no “safe” option, where a great outcome is guaranteed on most reasonable moral perspectives. Future decision-makers will need to get a lot of things right.

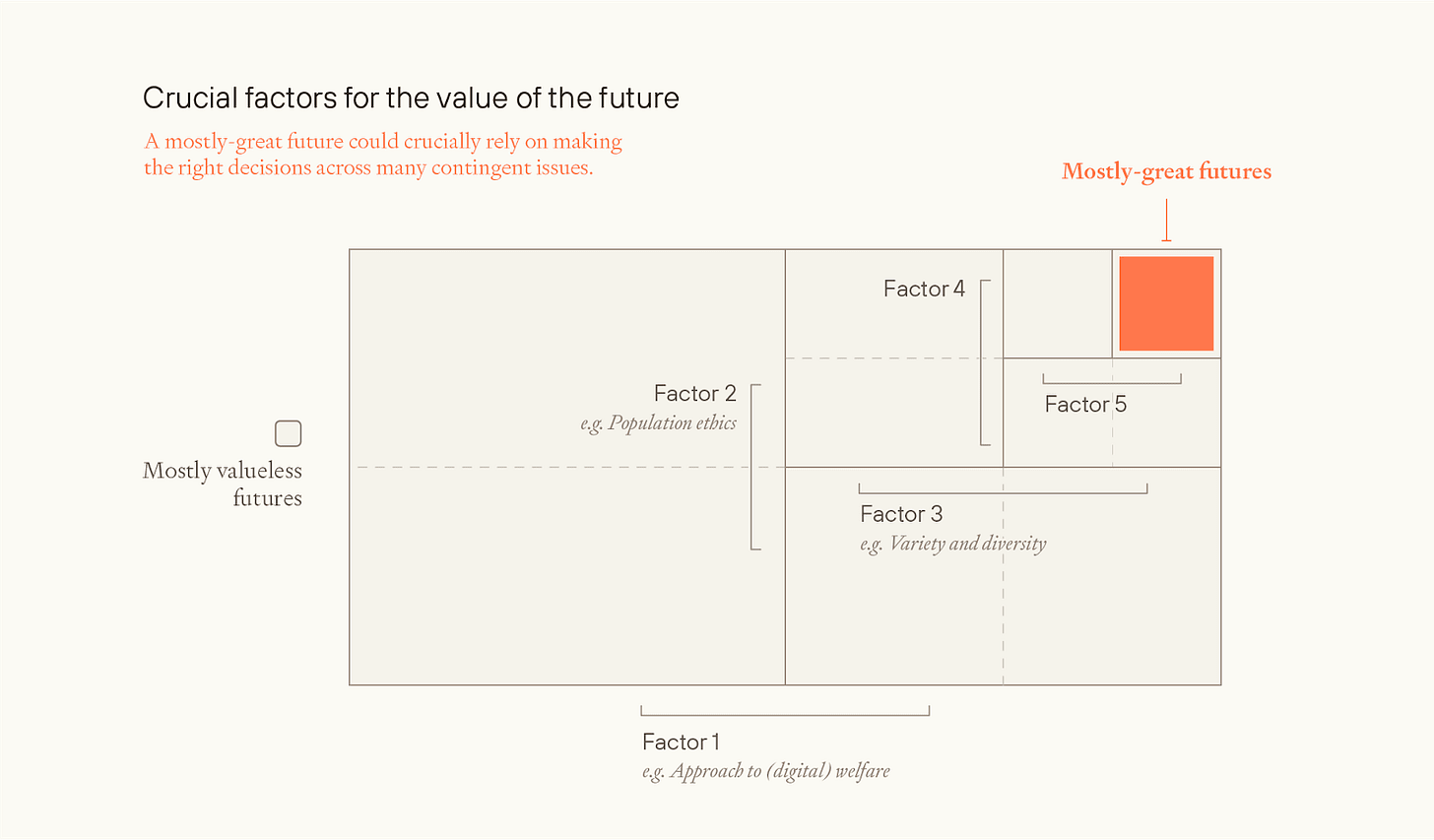

And it seems like getting just one of these wrong could be sufficient for losing much or most achievable value.

That is, we can represent the value as the product of many factors. If so, then a eutopian future needs to do very well on essentially every one of those factors; doing badly on any one of them is sufficient to lose out on most value.

How maximum achievable value varies with total resources

A different form of argument is more systematic.

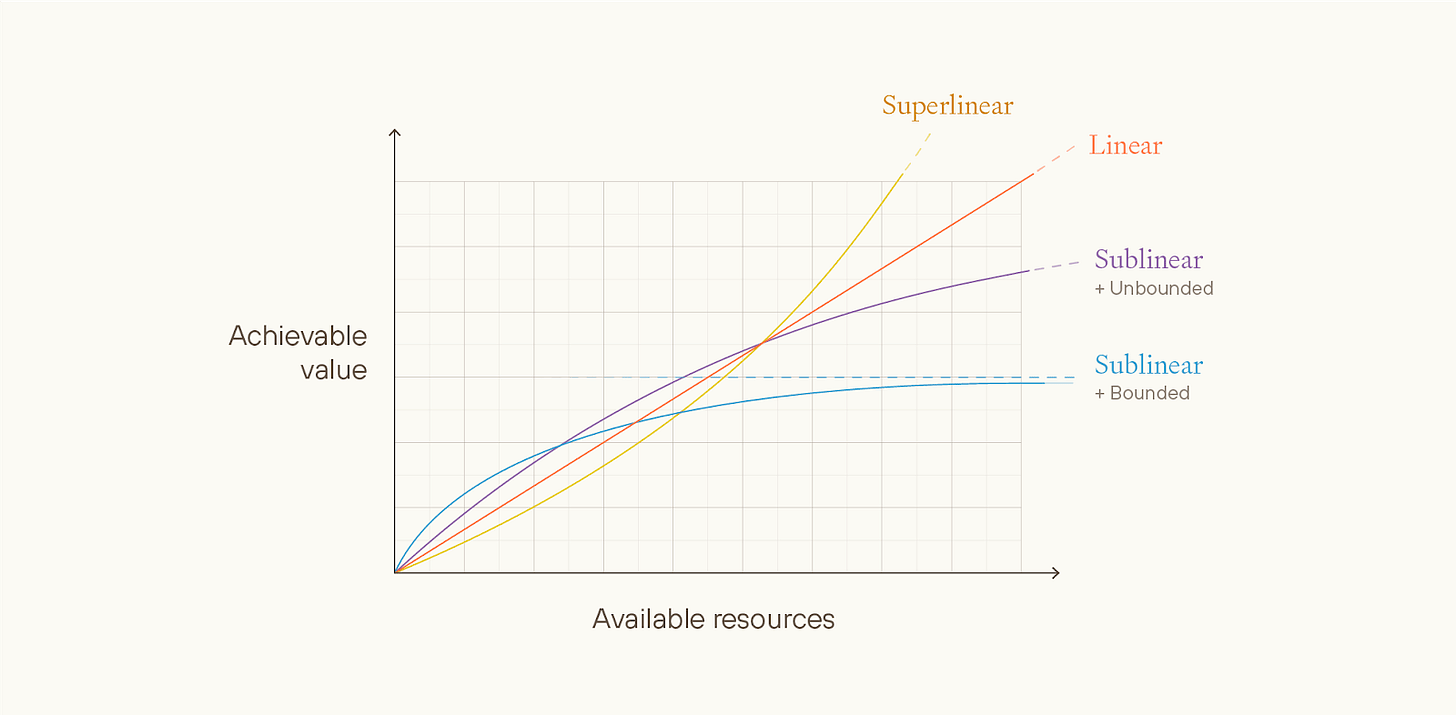

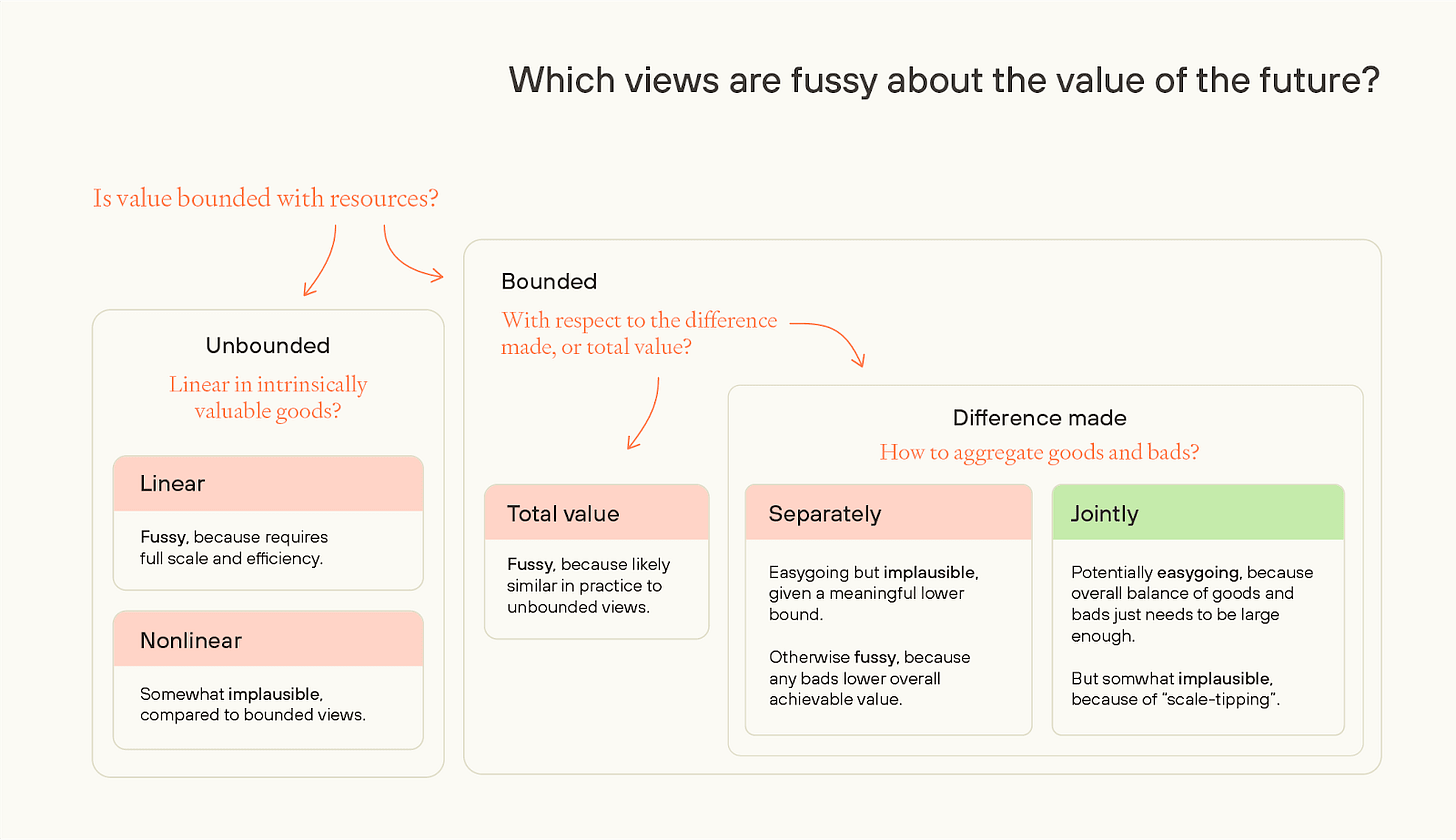

Some ways of valuing futures make it look comparatively easy to reach eutopia, because they regard a wide range of futures as close in value to the best feasible future. We’ll call these views easygoing. Other views make eutopia look comparatively hard; we’ll call these views fussy.

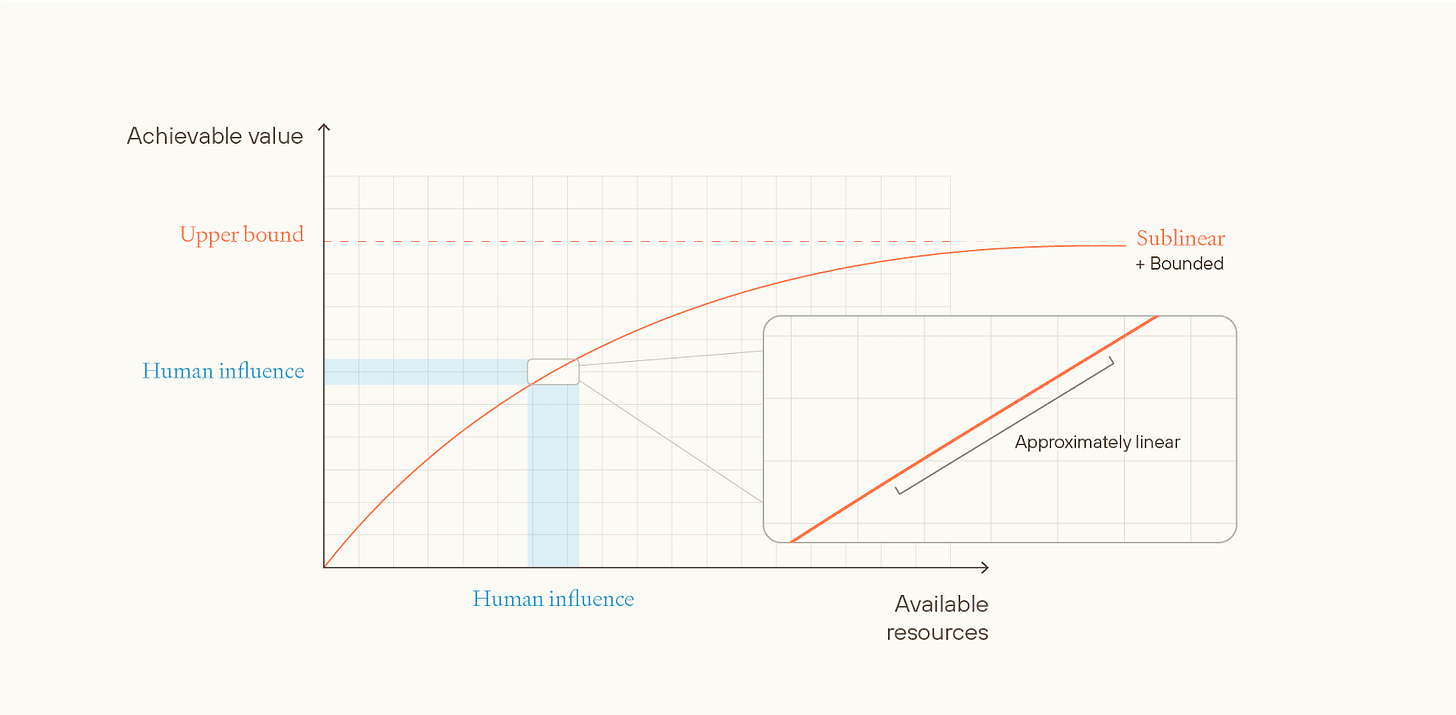

We can distinguish between different ethical views in terms of how much achievable value varies with total resources that could be used towards creating good outcomes, on these different views.

On unbounded ethical views, there’s no in-principle upper limit for maximum attainable value. Risk-neutral total utilitarianism is an example of an unbounded ethical view - any quantity of value is attainable as long as you have enough happy people.

Unbounded views could be approximately linear, superlinear, or sublinear with respect to the maximum achievable value that could be obtained with a given stock of resources.

Superlinear views seem very implausible and strictly fussier than linear views, and sublinear but unbounded views seem strictly less plausible and strictly fussier than sublinear and bounded views. So, in the essay, we don’t discuss either of them much.

Unbounded linear views are more plausible, but on such views, to reach a mostly-great future: (i) almost all available resources need to be used; and (ii) such resources must be put towards some very specific use.

E.g. on hedonistic total utilitarianism, almost all the accessible galaxies need to be used for whatever’s best. And, probably, the beings that experience joy most cost-effectively get a lot more joy per unit of resources than almost all other beings that could be created. This is a narrow target. More generally, the most plausible linear views are fussy.

Next, we can consider bounded views, meaning no possible world can exceed some fixed amount of positive value, even in theory.

If a view is bounded with respect to the value of the universe as a whole, then it will be approximately linear in practice.

This is because the value of the universe as a whole is very large, and the difference that even all of humanity can make to that value is very small, and over small intervals, concave functions are approximately linear. And linear views are fussy.

In contrast, if the view is bounded with respect to the difference that humanity makes to the value of the universe as a whole, it might still be approximately linear in practice, if the bound is extremely high.

If the bound is “low” (as it would be if it matches our ethical intuitions), then future civilisation might be able to get close to the upper bound, even with a small quantity of resources.

But such views might still be fussy depending on how they aggregate goods and bads.

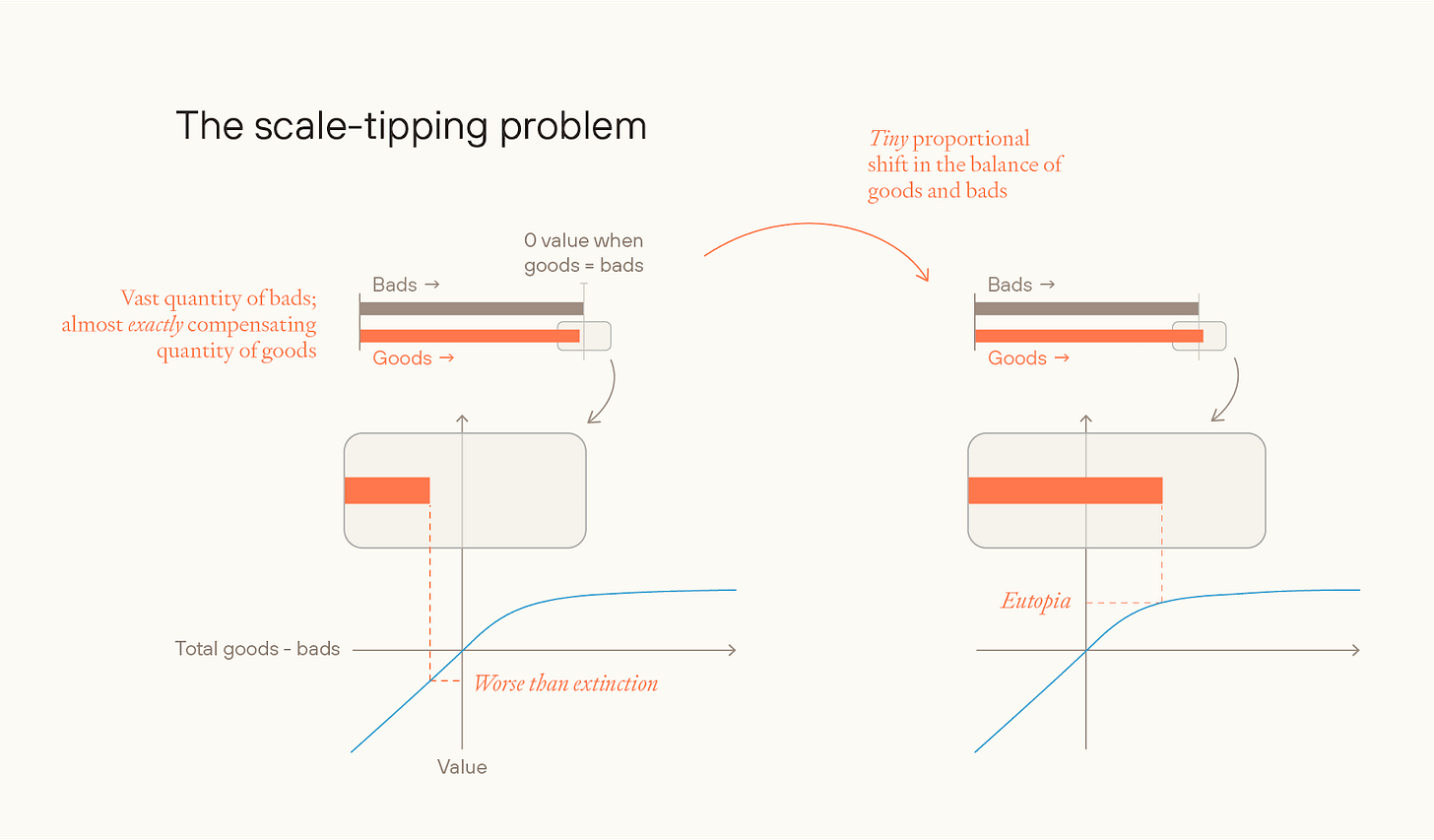

First, they could aggregate goods and bads separately, applying a bounded function to each of the amount of goods and amount of bads and then adding both. (I.e. the value of an outcome, v(o) = f(g) + h(b), where g and b are the quantities of goods and bads, respectively, and where f(.) and g(.) are bounded above).

But if so, then the value of the future becomes extremely sensitive to the frequency of bads in any future civilisation. Even if we weigh goods and bads equally (i.e. f(.) and g(.) are the same), then on a natural way of modeling we don’t reach a mostly-great future even if as little as one resource in 1022 is used toward bads rather than goods. So, such views are also fussy — requiring a future with essentially no bads at all.

Alternatively, you could aggregate jointly: i.e. you add up all goods and subtract the bads and then apply a bounded function to the whole. (v(o) = f(g – b)). If goods and bads are aggregated jointly, on a difference-making bounded view, then we plausibly have a view which is not fussy.

But this is quite a narrow slice of all possible views, and it suffers from some major problems that make it seem quite implausible. Some of the problems:

As noted, the value function has to concern the difference you (or humanity) make to the value of the universe. But such “difference-making” views have major problems, including that they violate stochastic dominance with respect to goodness. (These problems are described in more detail here.)

And separate aggregation seems at least as plausible as joint aggregation of goods and bads. Given joint aggregation of goods and bads, you have a “scale-tipping” problem, where a tiny change to the relative balance of goods and bads can move the value of the future from as-good-as- (or worse-than-) extinction, to eutopia.

Finally, any view that’s bounded above has to say implausible things about very bad futures, or else be strongly pro-extinction. If value is meaningfully bounded below, then in very bad worlds, the view will be willing to accept a very high likelihood of astronomical quantities of suffering in exchange for a small chance of a small amount of happiness.

If value is not meaningfully bounded below, then these views will generally become pro-human-extinction; the worst-case futures are much more bad than the best-case futures are good, so even a small chance of a very bad future can outweigh a much greater probability of even a near-best future.

Putting this all together, easygoingness about the value of the future seems unlikely to us.

To get regular updates on Forethought’s research, you can subscribe to our Substack newsletter here.

CarlShulman @ 2025-08-10T19:41 (+11)

Glad to see this series up! Tons of great points here.

One thing I would add is a that I think the analysis about fragility of value and intervention impact has a structural problem. Supposing that the value of the future is hyper-fragile as a combination of numerous multiplicative factors, you wind up thinking the output is extremely low value compared to the maximum, so there's more to gain. OK.

But a hypothesis of hyper-fragility along these lines also indicates that after whatever interventions you make you will still get numerous multiplicative factors wrong, so it will again be an extreme failure.

On this analysis it's the worlds where things are non-fragile (e.g. because of epistemic enhancement and improved bargaining and wealth driving systematically getting things right) that are far more valuable.

Maybe on the hyper-fragile aggregative story it's easier to 10x the value of the future, but after doing so it will still be a bunch of orders of magnitude off from the optimum. On the feasible convergent optimum story a win gets you the optimum, far better than going from 10^-10 to 10^-9 of the optimum.

So there's a lot of oomph to be had averting a catstrophic disruption of an otherwise convergent win (e.g. preventing a nasty whimsical permanent dictatorship that does crazy things or has a very bad starting point, AI or human), but not so much messing around with the hyper-fragile cases.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-11T09:40 (+4)

Glad to see this series up! Tons of great points here.

Thanks! And it’s great to see you back on here!

One thing I would add is a that I think the analysis about fragility of value and intervention impact has a structural problem. Supposing that the value of the future is hyper-fragile as a combination of numerous multiplicative factors, you wind up thinking the output is extremely low value compared to the maximum, so there's more to gain. OK.

But a hypothesis of hyper-fragility along these lines also indicates that after whatever interventions you make you will still get numerous multiplicative factors wrong, so it will again be an extreme failure.

Well, it depends on how many multiplicative factors. If 100, then yes. If 5, then maybe not. So maybe the sweet spot for impact is where value is multiplicative, but with a relatively small number of multiplicative factors.

And you could act to make the difference in worlds in which society has already gotten all-but-one of the factors correct. Or act such that all the factors are better, in a correlated way.

On this analysis it's the worlds where things are non-fragile (e.g. because of epistemic enhancement and improved bargaining and wealth driving systematically getting things right) that are far more valuable.

Great - I make a similar argument in Convergence and Compromise, section 5. (Apologies that the series is so long and interrelated!). I’ll quote the whole thing at the bottom of this comment.

Maybe on the hyper-fragile aggregative story it's easier to 10x the value of the future, but after doing so it will still be a bunch of orders of magnitude off from the optimum. On the feasible convergent optimum story a win gets you the optimum, far better than going from 10^-10 to 10^-9 of the optimum.

Here I want to emphasise the distinction between two ways in which it could be “easy” to get things right: (i) mostly-great futures are a broad target because of the nature of ethics (e.g. bounded value at low bounds); (ii) (some) future beings will converge on the best views and promote them. (This essay (No Easy Eutopia) is about (i), and Convergence and Compromise is about (ii).)

W r t (ii)-type reasons, I think this argument works.

I don’t think it works w r t (i)-type reasons, though, because of questions around intertheoretic comparisons. On (i)-type reasons, it’s easier to get to a meaningful % of the optimum because of the nature of ethics (e.g. value is bounded rather than unbounded). But then we need to compare the stakes across different theories. And normalising at the difference in value between 0 and 100% would be a big mistake; it seeming “natural” is just an artifact of the notation we’ve used.

We discuss the intertheoretic comparisons issue in section 3.5 of No Easy Eutopia.

And here's Convergence and Compromise, section 5:

5. Which scenarios are highest-stakes?

In response to the arguments we’ve given in this essay, and especially the reasons for pessimism about convergence we canvassed in section 2, you might wonder if the practical upshot is that you should pursue personal power-seeking. If a mostly-great future is a narrow target, and you don’t expect other people to AM-converge, then you lose out on most possible value unless the future ends up aligned with almost exactly your values. And, so the thought goes, the only way to ensure that happens is to increase your own power by as much as possible.

However, we don’t think that this is the main upshot. Consider these three scenarios:

- Even given good conditions, there’s almost no AM-convergence between any sorts of beings with different preferences.

- Given good conditions, humans generally AM-converge on each other; aliens and AIs generally don’t AM-converge with humans.

- Given good conditions, there’s broad convergence, where at least a reasonably high fraction of humans and aliens and AIs would AM-converge with each other.

(There are also variants of (2), where “humans” could be replaced with “people sufficiently similar to me”, “co-nationals”, “followers of the same religion”, “followers of the same moral worldview” and so on.)

Though (2) is a commonly held position, we think our discussion has made it less plausible. If a mostly-great future is a very narrow target, then shared human preferences are underpowered for the task of ensuring that the idealising process of different humans goes to the same place. What would be needed is for there to be something about the world itself that would pull different beings towards the same (correct) moral views: for example, if the arguments are much stronger for the correct moral view than for other moral views, or if the value of experiences is present in the nature of experiences, such that by having a good experience one is thereby inclined to believe that that experience is good.55

So we think that the more likely scenarios are (1) and (3). If we were in scenario (1) for sure, then we would have an argument for personal power-seeking (although there are plausibly other arguments against power-seeking strategies; this is discussed in section 4.2 of the essay, What to do to Promote Better Futures). But we think that we should act much more on the assumption that we live in scenario (3), for two reasons.

First, the best actions are higher-impact in scenario (3) than in scenario (1). Suppose that you’re in scenario (1), that you currently have 1 billionth of all global power,56

and that the future is on track to achieve one hundred millionth as much value as if you had all the power.57

Perhaps via successful power-seeking throughout the course of your life, you could increase your current level of power a hundredfold. If so, then you would ensure that the future has one millionth as much value as if you had all the power. You’ve increased the value of the future by one part in a million.

But now suppose that we’re in scenario (3). If so, you should be much more optimistic about the value of the future. Suppose you think, conditional on scenario (3), that the chance of Surviving is 80%, and that Flourishing is 10%. By devoting your life to the issue, can you increase the chance of Surviving by more than one part in a hundred thousand, or improve Flourishing by more than one part in a million? It seems to me that you can, and, if so, then the best actions (which are non-powerseeking) have more impact in scenario (3) than power-seeking does in scenario (1). More generally, the future has a lot more value in scenario (3) than in scenario (1), and one can often make a meaningful proportional difference to future value. So, unless you’re able to enormously multiply your personal power, then you’ll be able to take higher-impact actions in scenario (3) than in scenario (1).

A second, and much more debatable, reason for focusing more on scenario (3) is that you might just care about what happens in scenario (3) more than in scenario (1). Will’s preferences, at least, are such that things are much lower-stakes in general in scenario (1) than they are in scenario (3): he thinks he’s much more likely to have strong cosmic-scale reflective preferences in scenario (3), and much more likely to have reflective preferences that are scope-sensitive and closer to contemporary common-sense in scenario (1).

finm @ 2025-08-12T08:18 (+4)

Also note 4.2. in ‘How to Make the Future Better’ (and footnote 32) —

[O]n this model, making each factor more correlated can dramatically improve the expected value of the future — without improving the expected value of any individual factor at all.

Which could look like “averting a catstrophic disruption of an otherwise convergent win”.

CarlShulman @ 2025-08-11T14:08 (+2)

Thanks Will!

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-11T08:49 (+4)

Regarding the fussiness of different population-ethical theories, I will propose a not-fully-worked-out alternative to your bounded views, which seems more plausible to me. (Though overall linear unbounded seems most likely to me.)

The motivating intuition behind bounded views, I believe, is to reject (extreme) scope sensitivity, and to say that beyond some point, just more of the same good things has diminishing value. (But probably more of the same bad things does not diminish in disvalue, so there is some asymmetry.) One natural way to operationalise this would be to define the total value of the world as the average welfare of an individual, multiplied by some concave function of the number of individuals (but where this function is linear below 0). This is a joint view,[1] but avoids scale tipping because adding one more happy galaxy on top of countless others will barely change either the average welfare or the number of people. If the concave function has a sufficiently high ceiling, this just reduces to totalism (as average times number equals total) but with lower ceilings, this could capture the common-sense intuition against scope-sensitivity.

What do you think? I'm conscious there are impossibility theorems here, so no doubt my proposed theory would have some very counter-intuitive conclusions.

- ^

Aggregating goods and bads separately seems quite implausible to me, for starters it feels hard to say whether the unit of aggregation should be moments, or whole lives, or galaxies or something else.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-11T10:09 (+4)

This has been proposed in the philosophy literature! It's the simplest sort of "variable-value" view, and was originally proposed by Yew-Kwang Ng. (Although you add linearity for negative worlds.)

I think you're right that it avoids scale-tipping, which is neat.

Beyond that, I'm not sure how your proposal differs much from joint-aggregation bounded views that we discuss in the paper?

Various issues with it:

- Needs to be a "difference-making" view, otherwise is linear in practice

- Violates separability

- EV of near-term extinction, on this view, probably becomes very positive

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-14T19:29 (+2)

Good point, those seem like important weaknesses of the view (and this is partly why I favour totalism). And good to know re Yew-Kwang Ng. Yes, it is a version of your joint-aggregation bounded view - my main point was that it seemed like scale-tipping was one of your main objections and this circumvents that, but yes there are other problems with it as you note!

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-11T08:25 (+4)

Great essay.

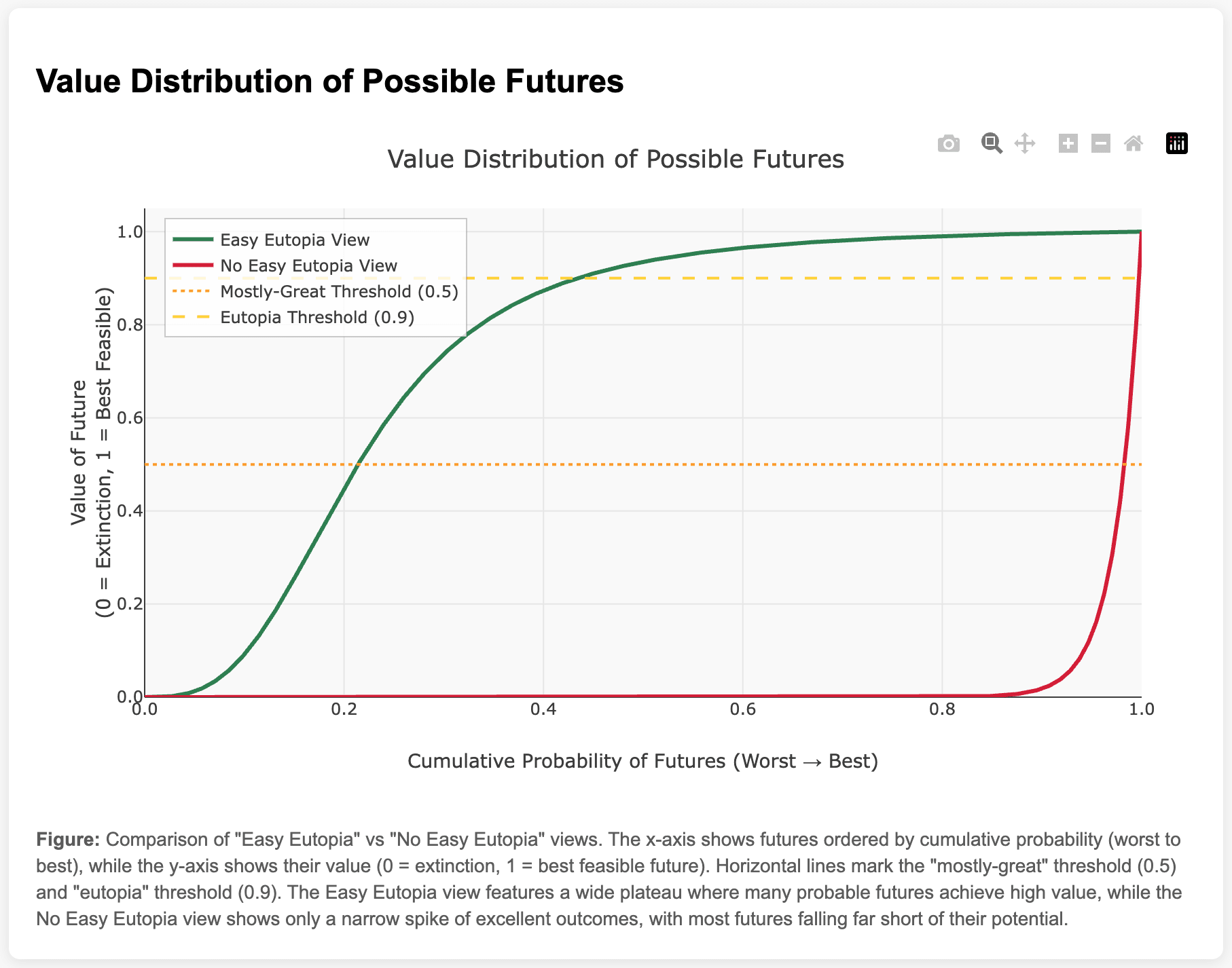

I liked the figures, but think a figure that would be quite valuable for explication was missing, something like this:

Relatedly, does anything important happen in the last 0.01% of best futures, I wonder? If one had a very extreme view, most of the value of the future would be in that best 10^-4 of worlds, and so normalising things by that point might not work as well. Implicitly I was assuming that 99.99th ~= 'best' ie that the scale as you have defined it doesn't go much past 1, but this seems not obvious.

(I will post my other comments separately)

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-11T09:50 (+6)

I like the figure!

Though the probability distiribution would have to be conditional on people in the future not trying to optimise the future. (You could have a "no easy eutopia" view, but expect that people in the future will optimise toward the good and hit the narrow target, and therefore have a curve that's more like the green line).

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-11T08:31 (+2)

(minor)

Next, we’ll define extinction as an outcome where the human population goes to 0, and is not replaced with a morally valuable successor. We’ll stipulate that guaranteed extinction has a value of 0.

Somewhat nit-picky, but this seems underspecified: e.g. if the population goes to zero in a very violent and painful way that would be negative, while if it goes to zero but the process takes a million (or a billion etc) years and is very benign and pleasant along the way, that should be positive. I assume you mean something like 'if everyone ceased to exist painlessly tomorrow'.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-11T09:48 (+4)

Thanks - that's fair. We were at least should have said "near-term extinction", and of course to define an outcome as exactly 0 we'd need to make it very specific.