Will morally motivated actors steer us towards a near-best future?

By William_MacAskill, finm, Forethought @ 2025-08-08T18:29 (+47)

To what extent, in the future, will we get widespread, accurate, and motivational moral convergence - where future decision-makers avoid all major moral mistakes, are motivated to act to promote good outcomes, and are able to do so? And, even if we only get partial convergence, to what extent can we get to a near-best future by different groups, with very different moral views, coming together to compromise and trade?

In a new essay, Convergence and Compromise, Fin Moorhouse and I (Will) discuss these ideas.

Given “no easy eutopia”, we’re very unlikely to get to a near-best future by default. Instead, we’ll need people to try really hard to bring it about: very proactively trying to figure out what’s morally best - even if initially counterintuitive or strange - and trying to make that happen.

So: how likely is that to happen?

Convergence

First: maybe, in the future, most people will converge on the best understanding of ethics, and be motivated to act to promote good outcomes, whatever they may be. If so, then even if eutopia is a narrow target, we’ll hit it anyway. In conversation, I’ve been surprised by how many people (even people with quite anti-realist views on meta-ethics) have something like this view, and therefore think that, even if the whole world were ruled by a single person, there would be quite a good chance that we’d still end up with a near-best future.

At any rate, Fin and I think such widespread convergence is pretty unlikely.

First, current moral agreement and seeming moral progress to date is weak evidence for the sort of future moral convergence that we’d need. Present consensus is highly constrained by what’s technologically feasible, and by the fact that so many things are instrumentally valuable: health, wealth, autonomy, etc. are useful for almost any terminal goal, so it’s easy to agree that they’re good. This agreement could disappear once technology lets people optimise directly for terminal values (e.g., pure pleasure vs. pure preference-satisfaction).

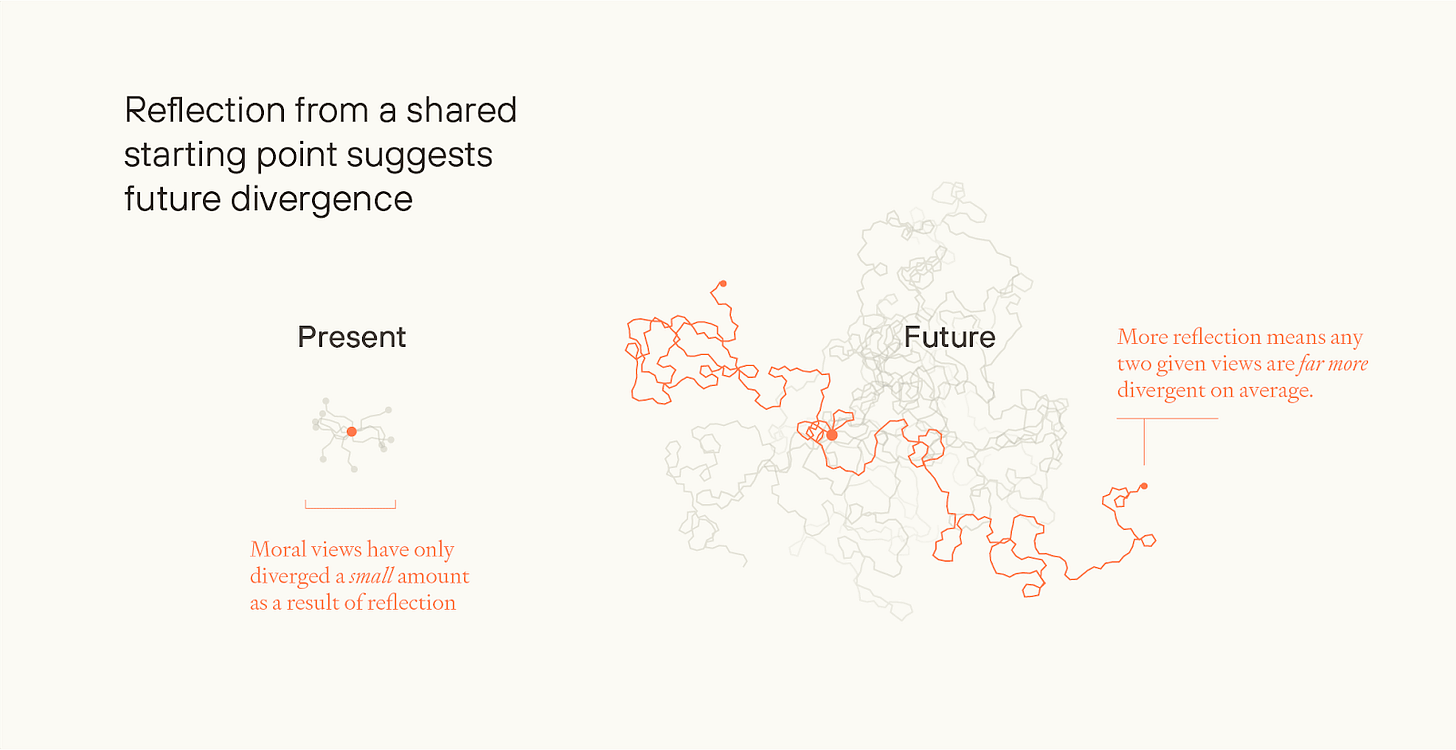

Compared to how much we might reflect (and need to reflect) in the future, we’ve reflected very little, to date. What might seem like small differences, today, could become enormous after prolonged moral exploration, especially among beings who can radically self-modify. Two people could be close to each other if they started off in the same spot and walked 10 metres in any direction. But if they keep walking for 100 miles, even slight differences in direction would lead them to end up very far apart.

What’s more, a lot of moral progress to date has come from advocacy and coalition-building among disenfranchised groups. But that’s not an available mechanism to avoid many sorts of future moral catastrophe - e.g. around population ethics, or for digital beings who will be *trained* to endorse their situation, whatever their actual condition.

Will the post-AGI situation help us? Maybe, but it’s far from decisive.

Superintelligent advice can make us reflect much more, but people might just not adequately reflect on their values, might not do so in time (see Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion), or might deliberately avoid reflection that threatens their identity, ideology, or self-interest. And if people had different starting intuitions and endorse different reflective procedures, then they could end up with diverging opinions even with superintelligent help.

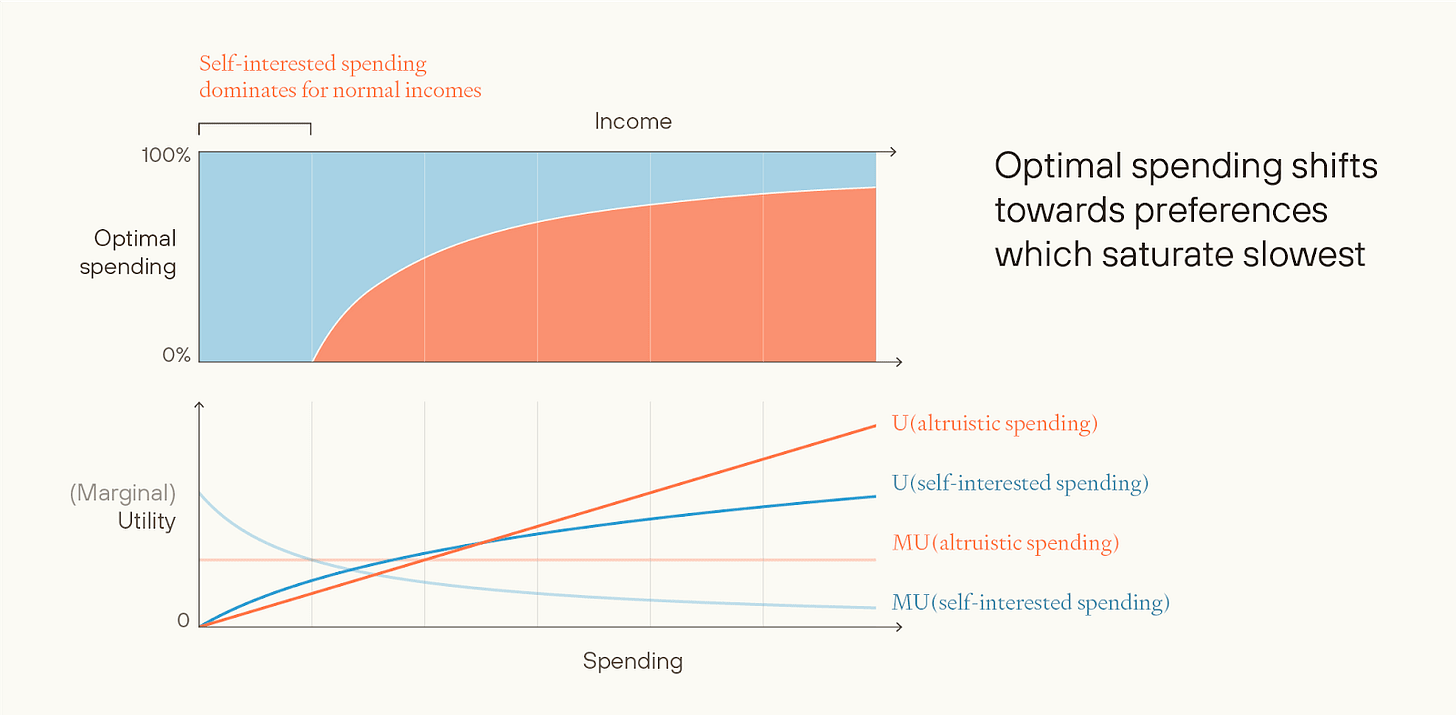

Sometimes people argue that material abundance will make people more altruistic: they’ll get all their self-interested needs met, and the only preferences left to satisfy will be altruistic.

But people could have (or develop) nearly linear-in-resources self-interested preferences, e.g. for collecting galaxies like stamps. (Billionaires put barely a greater fraction of their wealth towards charity, despite having many orders of magnitude more wealth than the middle class.) Or they could act on misguided ideological preferences - this argument doesn’t give a reason for thinking that they’ll become enlightened.

A more general argument against expecting widespread, accurate, motivational moral convergence is this: If moral realism is true, the correct ethics will probably be quite alien; people might resist learning it; and even if they do, they might have little motivation to act in accordance with it. If anti-realism is true, the level of convergence that we’d need seems improbable. Ethics has many “free parameters” (e.g. even if you’re a hedonistic utilitarian - what exact sort of experience is best?), and on anti-realism there’s little reason to think that differing reflective procedures would end up in the same place.

Then, finally, we might not get widespread, accurate, motivational moral convergence because of “blockers”. Evolutionary dynamics might guide the future, rather than deliberate choices. False but memetically powerful ideas might become dominant. Or some early decisions could lock in later generations to a more constrained set of futures to choose between.

Compromise

Even if widespread, accurate, motivational convergence is likely, maybe trade and compromise among people with different values will be enough to get us to a near-best future?

Suppose that in the future, most people are self-interested or favour some misguided ideology, but that some fraction of people end up with the most enlightened values, and want to devote most of their resources to promoting the good. Potentially, these different groups could engage in moral trade.

Suppose, for example, there are both environmentalists and total utilitarians. The environmentalists primarily want to preserve natural ecosystems; the utilitarians primarily want to spread joy as far and wide as possible. If so, they might both be able to get most of what they want: the environmentalists control the Earth, but the utilitarians can spread to distant galaxies.

Moreover, many current blockers to trade could fall away post-superintelligence. With AI help, there could be iron-clad contracts, and transaction costs could be tiny relative to the gains. And there might be many dimensions along which trade could occur. Some groups might value local resources, and others distant resources; some groups might be risk-averse, and others risk-neutral; some groups might time-discount, and others not.

I think this is the most likely way in which we get close to eutopia. But it’s far from guaranteed, and there are major risks along the way. I see three big challenges.

First, post-superintelligence, a lot of different groups might start to value resources linearly (because they’ve had the sublinear part of their preferences satisfied already). And it seems a lot less likely that you can get positive-sum trade between groups with linear preferences.

Second, threats. Some groups can self-modify, or form binding commitments, to produce things that other groups regard as bad unless those other groups give the threatener more resources. This is bad in and of itself, but if some of those threats get executed, then the kind of outcomes which many groups specifically don’t want could in fact materialise — a depressing possibility.

If threats aren’t prevented - and it might be quite hard to prevent them - then the future could easily lose out on much of its value, or even end up worse than nothing.

Finally, there are blockers to futures involving trade and compromise. As well as risks of evolutionary futures and memetic hazards, there’s also the risk of intense concentration of power, and the risk that trade could be prevented (e.g. tyranny of the majority). Perhaps the very highest goods just get banned. (Analogy: today, most rich countries have criminalised MDMA and psychedelic drugs; arguably, from a hedonist perspective, this is a ban on the best goods you can buy.)

I think the chance of getting partial accurate moral convergence plus trade and compromise is a good reason for optimism about the expected value of the future. At least when putting s-risks to the side (a big caveat!), I think it’s enough to make the expected value of the future comfortably above 1%. But I think it’s not enough to get close to the ceiling on “Flourishing” — my own best guess of the expected value of the future, conditional on Survival, is something like 5-10%.

To get regular updates on Forethought’s research, you can subscribe to our Substack newsletter here.

CarlShulman @ 2025-08-10T19:49 (+5)

[Duplicate comment removed.]

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-11T09:44 (+2)

Ah, I responded on the other comment, here.

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-11T18:14 (+2)

(more minor points)

If only a small number of people have power, then it becomes less likely that the correct moral views are represented among that small group, and therefore less likely that we get to a mostly-great future via trade and compromise.

I believe this is correct, but possibly for the wrong reason. If you just have a smaller group of people and they are drawn randomly from the population, yes there is a higher probability that no-one will have the correct moral view. But there is also a higher probability an unusually high fraction of people will have such a view. So a smaller bottleneck just increases the variance. But this is bad in expectation if you think that the value of the future is a concave function of the fraction of world power wielded by people with the correct values, because of trade and compromise. ie if having 10% of power in good hands is less than 10 times as good as 1%, as I understand you believe, then increasing variance by concentrating power is bad. (And of course, there is the further effect of power-seekers on average having worse values.)

In particular, we could model the process of reflection as a series of independent Brownian motions in R2, all starting at the same point at the same time. Then the expected distance of a view from the starting point, and the expected distance between two given views, both increase with the square root of time. The latter expectation is larger by a factor of sqrt(2).

The choice of two dimensions is unmotivated, so I don't trust the numbers, but the general effect seems right and would hold directionally even if there are e.g. 10 dimensions that people are going on a random walk through.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-12T09:12 (+4)

a smaller bottleneck just increases the variance. But this is bad in expectation if you think that the value of the future is a concave function of the fraction of world power wielded by people with the correct values, because of trade and compromise.

Yes, this was meant to be the argument, thanks for clarifying it!

finm @ 2025-08-12T13:09 (+2)

Thanks Oscar!

I believe this is correct, but possibly for the wrong reason.

The reason you give sounds right — for certain concave views, you really care that at least some people are bringing about or acting on the things you care about. One point, though, is that (as we discuss in the previous post) reasonable views which are concave in the good direction are going to be more sensitive (higher magnitude or less concave) in the negative direction. If you have such a view, you might also think that there are particular ways to bring about a lot of disvalue, so the expected quantity of bads could scale similarly to goods with the number of actors.

Another possibility is that you don't need to have a concave view to value increasing the number of actors trading with one another. If there are very few actors, the amount by which a given actor can multiply the value they can achieve by their own (even linear) lights, compared to the no-trade case, may be lower, because they have more opporunities for trade. But I haven't thought this through and it could be wrong.

The choice of two dimensions is unmotivated

Yep, totally arbitrary choice to suit the diagram. I've made a note to clarify that! Agree it generalises, and indeed people diverge more and more quickly on average in higher dimensions.

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-11T18:01 (+2)

Moral progress

Another partial explanation is that (putatively) as people get richer and happier and wiser and so forth, they just have more time and interest and mental/emotional capacity to think carefully about ethics and act accordingly. I’m not sure how much the psychological literature supports this, but e.g. even just ending the worst privations and abuses in childhood probably removes a lot of the left tail of morality, thus increasing the average. And so, if this is significantly right, as material and social progress continues, we will get some moral progress for free as well. I note your point in 2.3.2 that there isn't much correlation between wealth and charitable giving currently, which does seem evidence against my hypothesis. But richer people care more about 'post-material' issues in politics, and intuitively I still think there is some correlation between how well-off you are (broadly construed, not just wealth) and your interest in abstract ethics. But I agree this probably isn’t enough by itself to get everyone to converge to the correct values.

Another thought on why we might continue to see moral progress: Most people don’t care about discovering moral truths or seeking out the Good de dicto, and will just go along with the bare minimum of ethics required by polite society. But some people do actively seek the Good, and they will influence the rest of the population by osmosis over many generations. Even a slow steady tug in the right direction is enough to turn a massive oil tanker, ie collective human morality, in this analogy. But this crucially relies on some people seeking and having access to (upon reflection) the Good, which is not obvious. Note this is distinct from moral trade; it is more moral persuasion.

finm @ 2025-08-12T13:18 (+2)

as people get richer and happier and wiser and so forth, they just have more time and interest and mental/emotional capacity to think carefully about ethics and act accordingly

I think that's right as far as it goes, but it's worth considering the limiting behaviour with wealth, which is (as the ultra-wealthy show) presumably that the activity of thinking about ethics still competes with other “leisure time” activities, and behaviour is still sensitive to non-moral incentives like through social competition. But also note that the ways in which it becomes cheaper to help others as society gets richer are going to tend to be the ways in which it becomes cheaper for others to help themselves (or ways in which people's lives just get better without much altruism). That's not always true, like in the case of animals.

Good point about persuasion. I guess one way of saying that back, is that (i) if the "right" or just "less bad" moral views are on average the most persuasive views, and (ii) at least some people are generating them, then they will win out. One worry is that (i) isn't true, because other bad views are more memetically fit, even in a society of people with access to very good abstract reasoning abilities.

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-14T19:25 (+2)

Yeah good point that memetic fitness != moral truth. I suppose one could hope that as long as some people are pursuing moral truth, then even if truth and fitness are uncorrelated, that will be some push towards truth, even though there is a lot of drift/noise from random ideas being fit.

The bad case is if truth and fitness are anticorrelated for some reason. My guess is that is unlikely though? Except insofar as the moral truth ends up being really convoluted and abstruse, and then simpler ideas might be more fit. But even then, maybe the memetically fitter simple ideas (e.g. total utilitarianism?) might be close approximations of some really messy truth.

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-08T19:56 (+2)

Executive summary: In this exploratory essay, Will MacAskill and Fin Moorhouse argue that while widespread, accurate, and motivational moral convergence is unlikely, there’s still hope for a near-best future through compromise and moral trade between divergent value systems—though this outcome is fraught with risks and uncertainty.

Key points:

- Moral convergence is unlikely: Despite superficial present-day agreement, deeper moral reflection is likely to increase divergence due to differing foundational values, reflective processes, and the possibility of radical self-modification.

- Current alignment is misleading: Apparent consensus today often arises from shared instrumental goals rather than deep moral agreement, and may dissolve as technological capabilities expand.

- Material abundance doesn’t ensure altruism: Even with abundant resources, people may continue to prioritize self-interest or ideological goals, challenging assumptions that post-scarcity leads to moral enlightenment.

- Compromise may be more tractable: A more promising path may lie in moral trade and compromise between value systems, especially if supported by superintelligent facilitation and enforceable agreements.

- Three major risks to compromise: These include (1) diminishing room for trade once preferences become linear, (2) coercive threats distorting the future, and (3) structural blockers such as concentrated power or the suppression of minority values.

- Modest optimism about the future: MacAskill estimates the expected value of the future at around 5–10% of its theoretical maximum (excluding s-risks), contingent on partial convergence and successful moral trade.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.