The US AI policy landscape: Where to work to have the biggest impact

By 80000_Hours @ 2026-02-10T00:36 (+33)

The US government may be the single most important actor for shaping how AI develops. If you want to improve the trajectory of AI and reduce catastrophic risks, you could have an outsized impact by working on US policy.

But the US policy ecosystem is huge and confusing. And policy shaping AI is made by specific people in specific places — so where you work matters enormously.

This guide aims to help you think about where specifically to work in US AI policy so you can actually make a large impact.

In Part 1, we cover five heuristics for finding the most impactful places to work. In Part 2, we cover five policy institutions that we’d guess are the most impactful for AI and name specific places in each that are especially promising.

If you want to work in US policy, we also recommend the expert-vetted guides at Emerging Tech Policy Careers for practical advice on pathways into government and detailed profiles of key institutions.

Jump to our top recommended institutionsPart 1: How to find the most impactful places to work on AI policy

It’s hard to predict precisely when and where key AI policy decisions will happen, but you can position yourself for greater impact. The following five heuristics can help you judge where you could have the best shot at positively shaping the trajectory of advanced AI.

Prioritise building career capital

Early in your policy career, avoid tunnel vision on AI policy roles. Many entry-level positions worth considering won’t focus on AI. What usually matters more is building career capital — knowledge, context, networks, and credibility that let you navigate the policy world.[1]

For example, you won’t get to specialise on AI risks as an intern in Congress. (You’ll probably spend much of your time answering phones.) But you’ll gain tacit knowledge, networks, and credentials that may accelerate your career more than an AI-focused opportunity lacking these benefits.

Here are some questions to help figure out how much career capital a role might give you:[2]

- Who will I meet? Policy is highly network-driven, so who you’ll meet in a role is incredibly important for your future career. It’s rarely obvious which relationships will ultimately matter most, so finding roles where you can [build broad networks](https://emergingtechpolicy.org/tips/networking/?utm_source=80000hours.org&utm_medium=articles-the-us-ai-policy-landscape-where-to-have-the-biggest-impact) — ‘casting a wide net’ — often pays off.

- What will I learn? Consider how much you’d learn about (1) how people in DC actually talk and think, (2) how policymaking happens, and (3) the substance of your issue area.

- What skills will I develop? Look for places where you build (and get feedback on) broadly valued policy skills like clear writing, people and project management, and research and analysis.

- How strong a credential is this? Weigh factors like the institution’s reputation, how competitive the opportunity is, and the work outputs you’d gain (like contributing to publications or drafting policy memos).[3]

It can be hard to answer these questions by research alone — when possible, talk to people who’ve worked in or near the places you’re considering.

In short: Get your foot in the door, build relationships, and learn how policy works. Then cash out that career capital to move into more targeted, directly impactful roles.

Work backwards from the most important issues

AI policy is a huge and complex field — here are some ways to break it down:

| Inputs to AI development | AI applications | Policy levers |

|

|

|

You can mix and match across these columns and end up working on very different things. For example, you might work on R&D funding (investment) for military applications, or on export controls for AI chips. Your impact will depend on which issues you choose to work on and which levers you use.

You might start by asking: Which issues seem most important?[4] Then, work backwards to the policy tools that you think might address them most effectively. For example, if you’re most concerned about:

- Catastrophic misuse: You might work on [liability rules](https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3084-1.html) that hold companies accountable if their systems cause serious harm, or on [insurance](https://www.transformernews.ai/p/insurance-ai-secure-trout-dattani-kvist) mechanisms that reward firms for adopting stronger safeguards.

- Geopolitical competition over AI, potentially leading to conflict: You might push for international agreements that set shared safety standards or on compute governance — tying access to the most advanced chips to strong safety and security practices.

- AI takeover: You might focus on requiring safety evaluations before powerful systems are deployed, or on R&D funding to make AI systems more secure and auditable.

In practice, issues often overlap, and many policy roles let you pull on several levers at once — or one lever that mitigates several risks. Still, prioritising which AI issues matter most can help you zero in on the levers, and then the roles, best placed to address them.

Find levers of influence

Some policy institutions are far better equipped for work on your AI policy priorities, depending on what formal or informal powers they hold.

Formal powers are legal authorities,[5] like deciding what research and development priorities to fund, regulating individuals or companies, or setting interest rates.

For example:

- The Department of Defense[6] funds and deploys autonomous weapons.

- The Bureau of Industry and Security controls US exports of advanced AI chips.

- The Federal Trade Commission investigates and sues tech companies for anticompetitive practices.

Informal powers — like coordination, research and argumentation, and agenda-setting — aren’t enforceable, but they can be as (or more) important than formal ones. Many policy organisations have little budget or regulatory authority but can sway others that do.

For instance, White House offices can’t create new laws, but they can steer agencies toward their priorities and broker compromises among them.[7] Likewise, most think tanks and advocacy organisations don’t have formal powers, but they can influence Congress or the White House if they’re trusted advisors.

Both kinds of power matter. The most impactful institutions usually have one, or both, in abundance.

When you’re looking for impactful places, ask: Does this place control money or relevant rules directly? Or can it reliably influence those that do?[8]

Prepare for ‘policy windows’

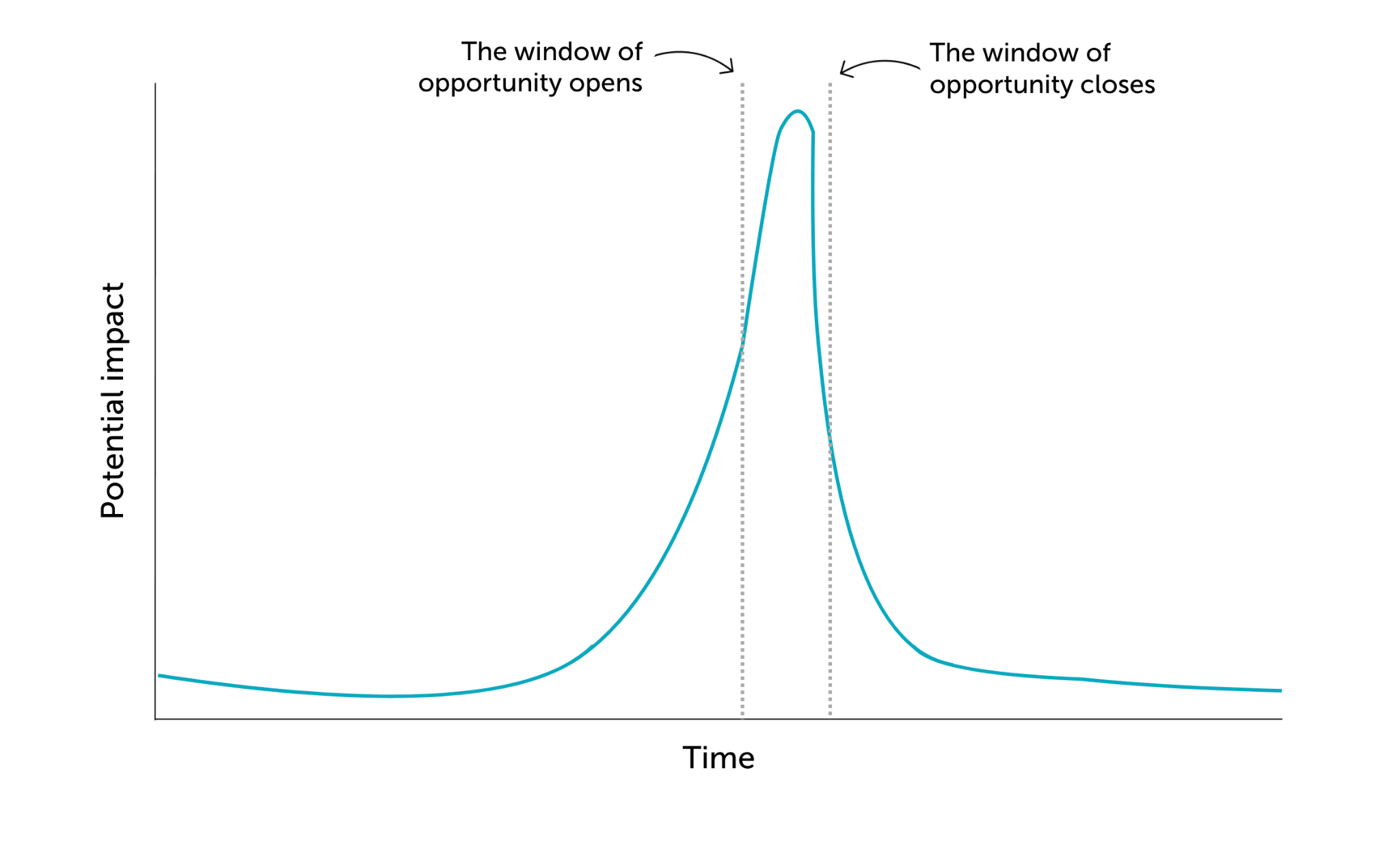

Timing matters a lot in policy. Sometimes a single crisis, scientific discovery, or article can catapult an issue onto the policy agenda overnight. Other times, it takes years of building evidence that something is needed before action finally breaks through.

These breakthrough moments are called ‘policy windows.’ It’s hard to predict when they’ll open. A few examples:

- 1.5 months after the 9/11 attacks, Congress passed the PATRIOT Act to vastly expand government surveillance and law enforcement powers.

- Four months after Upton Sinclair published The Jungle (1906), Congress passed new meat safety laws.

- Nine years after the Surgeon General linking smoking to lung cancer, Congress restricted cigarette advertising.

Your potential for policy impact can spike when a certain window opens:

For your career, this means:

- Build expertise and connections early. By the time an issue is ‘hot,’ you want to have the networks, credibility, and expertise to act quickly.[9] COVID-19, for example, turned long-time biosecurity specialists into go-to advisors trusted with major decisions almost overnight. If you only switch to working on an issue once a window of opportunity opens, you may be too late to make a big impact.

- Stay flexible. It’s hard to know which places will matter most in five years. Instead of working towards a narrow career goal, build broad career capital that you can ‘cash out’ in many directions.

- Think about your political affiliation.[10] Your party alignment (or lack thereof) can shape when windows open and close for you. This varies depending on where you work:

- In Congress, you almost always pick a party and stick with it, and switching later is rare.

- In the executive branch, civil servants are nonpartisan[11] and stay through presidential transitions. Political appointees are partisan and usually rotate out when power shifts.[12]

- Think tanks can be partisan or nonpartisan. These affiliations can constrain or boost your policy career depending on who’s in power.

In AI, there’s also the consideration of how quickly the technology is developing. Many think the most effective time to act is before AI systems get very powerful, which may be quite soon. If you think the most important AI policy decisions will be made in the next 3–5 years, you probably want to prioritise paths that focus on AI earlier while still developing career capital. That might mean:[13]

- Choosing shorter or part-time master’s programs over lengthy JDs or PhDs.[14]

- Applying for fellowships that can get you ‘in the room’ quickly, like Horizon or TechCongress.

- Considering congressional staff roles, which often require only a bachelor’s and may let you advance more rapidly.

Consider personal fit

Policy impact highly depends on your personal fit. If you’re especially well-suited for a particular policy role, you can often achieve vastly greater impact, and poor fit often leads to burnout.

Some traits matter for almost all policy work, like professionalism, humility, initiative, and being able to work with people who hold different views and values. But beyond that, different roles reward very different strengths. For example:

- Congress or White House roles might suit you if you could thrive in fast-paced, social, and politicised environments, work long hours, and cover a broad portfolio of issues.

- Think tank work can involve working on long-term research projects and distilling complex technical topics into policy recommendations.

- Federal agency roles often reward technical expertise and the ability to navigate bureaucracy.

- Advocacy roles tend to value networking, coalition-building, and persuasion skills to mobilise support for specific causes.

The stereotype of a suit-wearing, cocktail-reception-attending staffer captures only a slice of the policy world. Your most impactful role could be in any of the places we discuss below (or beyond), depending on your skills, interests, and preferred work style.

Part 2: Our best guess at the most impactful places (right now)

Below, we cover five policy institutions and give our best guesses for the most impactful places to work in each.[15]

1. Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President (EOP; aka the White House) is small but mighty. Its ~2,000 staff help implement the president’s agenda and oversee the ~three-million-person executive branch. Spread across over 20 offices, EOP influences everything from the federal budget to national security to science and technology priorities. The leaders of these offices are often the president’s closest advisors, and their guidance — shaped by their staff — can sway decisions at the highest level.

The White House matters for AI policy by:

- Setting agendas: The president sets priorities that agencies, Congress, and the public respond to.[16] Semiconductor policy is one case study:

- Under President Trump’s first term, the US mainly blacklisted specific Chinese firms like Huawei. Biden expanded those measures into sweeping, category-wide restrictions on advanced chips and AI hardware and coordinated allies to follow suit. In 2025, Trump rolled back the broad controls and shifted focus to enabling domestic AI progress.

- Moving quickly: Congress often moves slowly, but in some cases, presidents can make sweeping changes overnight (often via executive orders). In a fast-moving AI crisis, the White House is one of the only places in government that could respond in mere hours.

- Just 12 days after 9/11, President Bush signed an executive order creating sanctions to freeze assets of designated terror organisations.

- Proposing the budget: Almost every new government program, office, or regulation needs money. Each year, the president sends a budget request to Congress, proposing how to spend roughly $6 trillion. Congress decides the final numbers, but the proposal sets a starting marker and signals priorities that lawmakers (especially in the president’s party) may hesitate to oppose.[17]

- Leading US foreign policy: The president is especially empowered in foreign affairs, with the ability to recognise foreign governments, negotiate international agreements, and command military operations.

- When the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted in 1962, President Kennedy imposed a naval quarantine and negotiated directly with USSR leader Khrushchev over 13 days. Congress wasn’t convened to debate the response.

- Gaining power: In recent decades, the White House has increasingly stretched the limits of its power, often through novel interpretations of existing laws and regulations, selectively enforcing or declining to enforce laws, or declaring national emergencies.[18] While not always upheld in court, actions like these shift expectations of what the presidency can get away with and gradually expand the White House’s reach.

- President Trump used executive orders (EOs) to impose blanket tariffs, claim authority to end birthright citizenship, and pause a law banning TikTok.

- President Biden tried to cancel up to $400 billion in student loans and mandate COVID-19 vaccines or weekly testing for employees of large companies without new legislation.

- President Obama used an EO to shield millions of undocumented immigrants from deportation after Congress rejected his immigration bill.

The White House also has some key institutional constraints. Being so far upstream, the White House doesn’t get much ‘ground-level’ visibility into how policies are developed and carried out. Compared to the whole executive branch, White House offices have very small staffs and budgets, and most largely rely on soft powers to achieve their policy goals.

Here are some key career considerations for working in the White House:

- Security clearances: Most White House roles require a clearance, which can take months to more than a year and could be harder to get if, for example, you’ve used illegal drugs or have concerning foreign ties.[19]

- Partisan considerations: Roughly 10% of White House staff are political appointees, who the president nominates to serve in leadership roles.[20] The rest are nonpartisan career civil servants, generally hired through public openings.[21] All staff are expected to advance the administration’s policies, regardless of their personal positions.

- Strong credentials help: Elite law, policy, or technical graduate degrees can be highly valued — under Biden, 41% of mid- or senior-level staffers had Ivy League degrees. Few people start their policy careers in the White House; most arrive with years of prior experience in Congress, federal agencies, or think tanks. Strong networks and proven expertise can sometimes substitute for formal credentials.[22]

- There isn’t much stability: Most White House political appointments last at most until the end of an administration (but they’re often much shorter).

- Intensity: White House jobs are notoriously demanding, with long hours, high stakes, and little control over your schedule. Staff constantly react to headlines and crises, which can make it hard to focus on long-term priorities. In former White House Adviser Dean Ball’s words: “The pace and character of your workday can change at a moment’s notice — from ‘wow-this-is-a-lot’ to ‘unbelievably-no-seriously-you-cannot-fathom-the-pressure’ levels of intense.”[23]

- Exit opportunities: White House credentials are highly prestigious in DC. Alumni often move into senior agency jobs, think tank positions, or return later in more senior political roles.

In short, White House roles can be exceptionally impactful — you’re close to the president, shaping government-wide agendas, and often in the room for time-sensitive, pivotal decisions. But they’re also typically short-lived and intense, tied to political cycles, and sometimes only as effective as your ability to rally the much larger machinery of government behind you.

Based on how much they have historically influenced technology policy, their overall levels of soft and hard power, and their potential for building career capital, we’d guess that the following offices would be especially impactful choices for AI policy:

- White House Office

- Office of Management and Budget

- National Security Council

- Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Office of the Vice President

2. Federal departments and agencies

Federal departments and agencies implement policy: they administer social programs, guard nuclear stockpiles, break up monopolies, approve new drug trials, launch satellites, and train the military, among thousands of other things. Most people and money in the US government sit in these departments.

Departments are massive and specialised, with tens or hundreds of thousands of employees spread across dozens of sub-agencies. Fifteen secretaries (the Cabinet) lead the 15 Departments.[24]

Federal departments and agencies can matter for AI policy by:

- Shaping how policies get implemented: Agencies carry out the work that laws, executive orders, and other policy directives set in motion. Much of a policy’s impact depends on how it is interpreted, put into practice, and enforced. For example, agencies:

- Set export controls for critical technologies and materials.

- The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), inside the Department of Commerce, can restrict or block US companies from selling to foreign entities when doing so could threaten national security. BIS spells out which items get controlled and where they can (or can’t) go.

- Fund and manage research and development (R&D) — roughly $200 billion annually — that steers innovation toward national priorities.

- Set technical standards and develop evaluations for systems that may pose national security risks.

- The Center for AI Standards and Innovation (CAISI) leads evaluations of the capabilities of US and adversary AI systems. CAISI coordinates government and industry efforts to test and evaluate advanced AI models. CAISI is building methods to measure model capabilities, safety, and reliability, including red-teaming for potential misuse or loss-of-control scenarios.

- Write and enforce rules that put laws into action.

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforces consumer protection and competition laws that increasingly apply to AI. For example, the FTC has investigated companies for making deceptive claims about ‘AI-powered’ products and for using algorithms trained on illegally obtained or biased data.

- Decide how the military will use AI.

- The Department of Defense tests and integrates AI tools for logistics, intelligence analysis, and battlefield decision making — for example, using algorithms to spot patterns in satellite imagery, plan supply routes, or to make vehicles or aircraft autonomous.

- Protect critical infrastructure from AI-enabled threats.

- The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the Department of Energy assess how AI could introduce new vulnerabilities to power grids, communications networks, and other critical systems and test tools to defend against these risks.

- Set export controls for critical technologies and materials.

- Spending enormous budgets: Federal agencies collectively spend trillions each year. Most of that is locked into programs like Social Security and Medicare, but the flexible remainder is still massive. In 2024, for example, departments spent about $11 billion on autonomous military applications, $1 billion on AI-enabled supercomputing, and $69 million on national AI research institutes.[25]

With their huge scope comes important limitations. Agencies answer to both Congress and the president: Congress sets their missions and budgets through laws, and the White House directs their day-to-day operations and high-level priorities. And as enormous, specialised bureaucracies, departments tend to develop entrenched procedures and risk-averse cultures that can make change slow.

Here are some key career considerations for working in federal agencies:

- Diverse role options: Agency staffers’ work is incredibly diverse. Some design new R&D programs, some run lab experiments as government scientists, others manage multimillion-dollar defense contracts. So it’s hard to determine your personal fit for working in federal departments generally — you’ll need to research specific roles and offices.

- Career vs political appointments: The vast majority of agency staff are career civil servants who stay through changes in administration. The most senior roles are typically filled by political appointees — people nominated by the president to serve for the duration of that administration.

- Security clearances: Many roles — especially those touching defense, intelligence, or foreign policy — require clearances.[26]

- Byzantine hiring: Agency hiring is infamously slow, opaque, and bureaucratic. Formatting requirements are strict, criteria can be idiosyncratic, and it’s not unusual to wait months before hearing back. Fellowships can help you bypass many standard hiring hurdles.

Our best guess at the five most impactful federal departments for AI policy:

3. Congress

Congress formally holds some of the most important levers in government: setting the federal budget and making laws. This means most big, lasting policy changes need buy-in from Congress.

Congress matters for AI policy by:

- Setting the federal budget: While the president proposes a budget, Congress holds the power of appropriation and sets the US government’s ~$6 trillion annual budget.

- Writing laws: Only Congress can pass binding national laws. And many important actions can only happen through laws: for example, creating or abolishing federal agencies, raising taxes, or setting immigration law.[28] Executive orders by the president can’t override laws.

- Overseeing the executive branch: Once laws are on the books, Congress makes sure agencies carry them out as intended. It uses a host of tools: public hearings, letters from members, reporting requirements, and subpoenas. It can also override presidential vetoes.

- Shaping the public agenda: Congress makes news. Hearings, press conferences, votes, and public statements can draw attention to neglected issues, push companies to change behaviour, or draw fringe ideas into mainstream debate.

On the flip side, Congress isn't exactly known for its efficiency.

There’s good reason for this scepticism:

- Slowness: Even bills with majority support can stall for months or years if they don’t fit leadership’s priorities or the bill agenda.

- Low yield: Stand-alone bills rarely pass, meaning most policy changes need to hitch a ride on ‘must-pass’ bills like the annual budget bill or the National Defense Authorization Act. This creates lots of veto points and often means that good ideas are diluted, delayed, or dropped altogether.

- Politics and showmanship: Congress members’ top priority is usually getting reelected.[29] This can make them prioritise short-term wins and benefits to their district over long-term national priorities. Political dynamics can also make bipartisan cooperation costly, and some offices focus more on messaging or ‘just-for-show’ bills than on substantive legislating.[30]

- Executive ‘power creep’: US policy influence has steadily shifted to the executive branch in recent decades. Congress still controls the budget and can pass durable laws, but in practice, more policy action now happens in the executive branch.

But Congress is easy to underestimate. The more polarised and theatrical something is, the more coverage it tends to get. This means bipartisan policymaking is often underrepresented in the news. (You probably never heard about Congress funding $175 billion to upgrade public water systems in 2020 or raising the tobacco purchasing age from 18 to 21 in 2021).

You’ll need to consider three major structural dynamics when finding roles in Congress:

- Senate vs House office: Senators usually carry more weight than representatives. There are only 100 senators compared to 435 house members, and each senator represents an entire state rather than a single district. They serve longer terms, sit on more committees, and have larger, more specialised staff. Senate rules also give individual senators unusual power: single senators can more easily stall legislation, demand concessions, or tip the balance on close votes.

- Committee vs personal office: Most staffers work in personal offices, where they support a single member of Congress. These offices are sometimes described as 535 small businesses, each with its own priorities, culture, and way of doing things. Personal office staff tend to juggle many different tasks and subject matter areas. Committees, on the other hand, do most of the heavy policy lifting. Committees ‘mark up’ bills and decide whether to move them forward (or kill them). Because every bill must pass through a committee, staff working on them often have more direct sway over policymaking.[31]

- Majority vs minority party: The majority party sets the agenda: it controls committee chairs, decides which bills come up for votes, and generally has an easier time moving forward legislation. You can still build valuable career capital in the minority party, but your direct impact may be more limited.

Impact rules of thumb: All else equal, Senate offices usually matter more than House offices, committees more than personal offices, and the majority more than the minority.[32]

But an office’s culture and your specific role in it matter greatly for your work experience and impact. For instance, some offices are highly hierarchical and top-down; others give junior staff more autonomy in writing legislation, leading meetings, or managing issue portfolios. These dynamics are hard to research, so prioritise talking with current or former staff who can give you a fuller picture.

Many people who thrive elsewhere in government find the Hill uniquely chaotic and political. This means you should think carefully about your fit — but also means that if you are a good fit, you may have an unusual comparative advantage.

Here are some career considerations for working in Congress:

- Relationship-driven: The ‘Hill’ runs on networks. Success depends on trust and coalition-building with other offices, committees, lobbyists, and advocates, so your reputation and relationships often matter more than your title.[33]

- Partisan: You’ll almost always work for one party, which could constrain or boost your later career moves. Navigating political dynamics is part of day-to-day policy work.

- Few entry barriers and fast progression: Most offices have clear pecking orders, but strong-performing staffers can advance rapidly (potentially moving from intern to an influential policy role in 2–3 years) and most roles require few formal credentials.

- Unpredictability: When Congress is in session, 60+ hour weeks are common, and work can stretch late into the night. Workdays are fast-paced and unpredictable — you may juggle several urgent issues at once with limited guidance. Long-term job security is rare given electoral cycles.

- Lower pay: Entry-level congressional salaries are notoriously underpaid (senior staff salaries are usually more reasonable).[34]

- Big and broad portfolios: Many congressional staff own substantive, ‘mile-wide’ portfolios early in their careers, which means you’ll learn rapidly across wide-ranging issues but may find it hard to focus exclusively on what you care about most.

- Strong career capital: Hill experience is prized in DC. Three years as a congressional staffer often signals deeper, more applied policy and political know-how than three years at a think tank. The relationships you build in Congress often uniquely open doors across the policy world.

Our best guess at the five most impactful Senate and House committees for AI policy:[35]

| Senate committees | House committees |

4. State governments

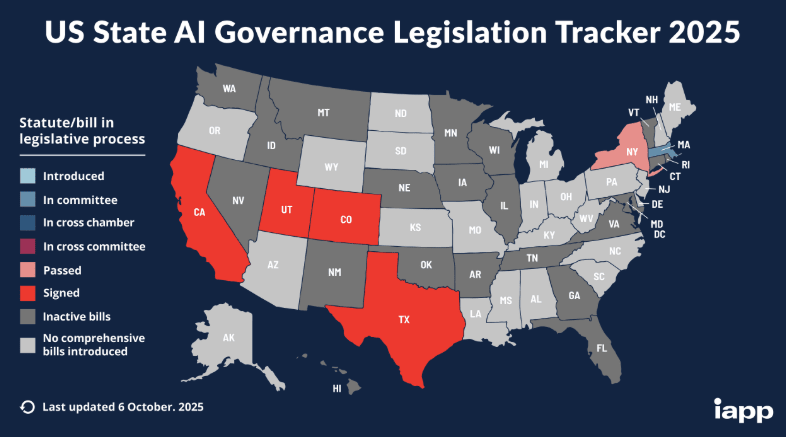

State legislatures and executive agencies don’t command headlines as much as Congress, but they often move much faster. Many state legislatures are dominated by a single party, which means fewer veto points and less gridlock. They’re also closer to the communities and industries they govern. And because state staff are usually smaller and thinner on technical expertise, one capable hire can have an outsized influence.

This agility and leverage make states important players in AI policy.[36] For example, California Governor Newsom signed SB 53 into law in September 2025, which introduces frontier AI lab whistleblower protections and safety incident reporting and requires large developers to publish their plans for mitigating catastrophic risks. In January 2026, New York enacted the RAISE Act, which also introduces transparency-focused rules for frontier labs.[37]

States shape AI outcomes on two fronts: locally, within their borders, and nationally, by influencing federal policy and industry behavior.

- Local powers: States directly control huge areas of daily life — from education and health to infrastructure and business regulation — and they implement many federal programs with wide discretion. This means that in states that host frontier AI companies or data centers, policy choices can directly affect how advanced AI is developed and deployed.[38]

- National effects: States can set precedents that are picked up by other states or the federal government — for example, Massachusetts pioneered vaccination mandates, Florida broke ground on computer crime laws, and Minnesota shaped data privacy rules for the entire country. Big companies often treat rules imposed by major states as de facto national standards (‘the California Effect’).[39]

As with federal policy, those working at the state level will have to choose between policy institutions, such as state legislatures, government agencies or executive offices (like the governor’s office), or state-focused think tanks or advocacy organisations. The tradeoffs between these options often mirror those at the federal level, but each state also has its own quirks that can change the calculus. For instance, it matters whether a state legislature has unified or divided party control, meets year-round or only part of the year, and whether members have their own staff or share them with leadership.

State AI policy also faces a major vulnerability: Congress can often override it. When federal and state laws clash, federal law typically wins, and Congress can sometimes go further by barring states from regulating in an area altogether.[40]

This risk is ever-present: In June 2025, Congress considered a 10-year ban on certain state AI laws.[41] And, as of December 2025, the threat to state legislation is back in the form of an executive order aimed at weakening state-level AI regulations through litigation, conditional federal funding, and by creating a federal framework to preempt state laws.

Here are some key career considerations for working in state-level AI policy:

- Launchpad for federal roles: State experience offers great skill-building for federal work. You see firsthand how federal programs get implemented and hone skills that transfer to DC. (But your state-specific network and knowledge may not matter much outside your state.)

- Access: State jobs are generally less competitive than federal ones, which means you can get in the door faster and often take on more responsibility earlier. They’re also available in every state, which is great if you’re tied to a specific region, or just not looking to move to DC.

- Intensity in bursts: Many state legislatures are only in session for a few months of the year, or every other year. During sessions, state legislative staff often face long, brutal hours — especially in states with biennial legislatures like Texas, where most policymaking is crammed into five months every two years. Agencies and advocacy groups usually have smaller staffs than their federal cousins, so expect to juggle many hats.

- Job security: In state legislatures, some positions are ‘session-only’ and even ‘safe’ legislative jobs can disappear after redistricting, retirements, or intraparty drama.[42] Like in Congress, staff job security often rises and falls with their boss’s electoral fortunes.

All else equal, federal policy usually has a higher ceiling for impact. But state roles are often more accessible, easier to land, and — particularly in influential states — could bypass gridlock at the federal level to shape AI trajectories nationally.

Our best guess for the five most impactful states for AI policy:

- California

- New York

- Texas

- Florida

- Washington

Within states, we think the highest-impact roles are usually in the legislature, the Governor’s office, or in agencies that implement relevant AI policies.[43]

5. Think tanks and advocacy organizations

Policymakers have little time to think deeply about the range of issues they have to cover. Think tanks can do it for them: they conceive, analyse, and push for ideas, serving as ‘idea factories.’ Advocacy organisations play a similar role, but usually with a sharper ideological edge or a specific mission. The lines between think tanks and advocacy organisations can be blurry in practice, and some policy-focused nonprofits don’t clearly fall in either category.[44]

Think tanks influence policy through several routes:

- Informing policymakers: Think tanks’ core business is to generate and communicate ideas. The most effective think tanks don’t just publish 50-page reports and hope someone reads them: they build trust with staff and officials, which lets them put ideas and research in front of the right person at the right moment.

- Talent pipelines: New administrations often pull talent from ideologically aligned think tanks to fill political roles, especially during the transition period when thousands of political appointees are selected. This revolving door lets think tanks exert influence indirectly, as their alumni carry their ideas and priorities into government.

- Shaping narratives: Public writing can shift policy windows, changing what policy proposals are politically viable. Even if a proposal isn’t adopted, putting it into debate can raise its profile and nudge policymakers to treat it more seriously. Especially for policies with broad and diffuse benefits, persistent advocacy from a dedicated actor can be highly impactful in moving the needle.

Advocacy organisations may also use these channels, but generally focus more on lobbying — for instance, meeting with policymakers to push their agenda or mobilising constituents to call their senators about an issue.

The biggest drawback of think tank and advocacy work is distance from actual decision makers. This makes their impact especially ‘lumpy’ — sometimes very high, but generally sporadic and hard to predict. In one think tank staffer’s words:

If we judge [think tanks] by whether they are successful in getting policy implemented, most would probably fail most of the time.

— Andrew Selee, former executive vice president of the Woodrow Wilson Center

If you’re just starting out, you might have some direct policy impact in a think tank, but the bigger payoff is usually career capital. Think tanks let you test whether you enjoy policy work, build skills valued in the policy world, and grow your network. Many junior congressional staffers come from think tanks, where they’ve built early credibility and relationships. And sometimes, junior researchers ‘ride the coattails’ of a senior staffer into a new administration, landing entry-level political roles when their boss gets appointed.

Some think tanks and advocacy organisations that we think could be impactful for AI policy are:[45]

| Think tanks | Advocacy orgs |

|

|

Conclusion

The tl;dr on how to have a big impact in US AI policy: build career capital, work backward from the most important issues, prioritise institutions with meaningful power, stay ready for policy windows with AI ‘timelines’ in mind, and choose roles that fit your strengths.

We think especially promising options include the White House, federal departments like Commerce and Defense, Congress (especially on relevant committees), major state governments like California (assuming state legislation remains feasible), and well-connected think tanks or advocacy organisations. But your personal fit really matters: the ‘best’ place to work in the abstract may not be the best place for you.

Learn more about how and why to pursue a career in US AI policy

Top recommendations

- Emerging Tech Policy Careers has 100+ guides on how and where to work in US AI policy. We recommend:

- AI policy resources (lists of readings, newsletters, podcasts, fellowships, and more)

- This database of US policy fellowships

- In-depth guides on working in US policy institutions (e.g. Congress, think tanks, and the executive branch)

- Pathways into US policy work (e.g. graduate school, policy internships, and short-term policy programs)

- Policy career essentials (e.g. intro to policy careers, testing your fit, professional development)

- Our AI governance and policy career review

- AI Governance Course from BlueDot Impact

Further reading

Resources from 80,000 Hours

- Article: Working in US AI policy

- Article: Policy and political skills

- Podcast: Tom Kalil on how to have a big impact in government & huge organisations, based on 16 years’ experience in the White House

- Podcast: Tantum Collins on what he’s learned as an AI policy insider

- Podcast: Helen Toner on the geopolitics of AI in China and the Middle East

- Podcast: Ezra Klein on existential risk from AI and what DC could do about it

- Podcast: Will MacAskill on AI causing a “century in a decade” — and how we’re completely unprepared

- Podcast: Toby Ord on graphs AI companies would prefer you didn’t (fully) understand

- Podcast: Allan Dafoe on why technology is unstoppable & how to shape AI development anyway

- Podcast: Lennart Heim on the compute governance era and what has to come after

- Podcast: Holden Karnofsky on dozens of amazing opportunities to make AI safer — and all his AGI takes

- Podcast: Carl Shulman on the economy and national security and government and society after AGI

- Podcast collection: The 80,000 Hours Podcast on AI

Resources from others

- Statecraft newsletter and podcast by Santi Ruiz

- Transformer newsletter and podcast by Shakeel Hashim

- Podcast: How to Build a Career in AI Policy by CSIS

- FAQs and General Advice on AI Policy Careers by Miles Brundage

- How to get into AI policy? by B Cavello

- Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Paul Scharre

- The New Fire: War, Peace, and Democracy in the Age of AI by Ben Buchanan and Andrew Imbrie

- Policy Entrepreneurship at the White House by Thomas Kalil

- AI governance database AGORA, by CSET

- US government strategies, such as the White House’s 2025 AI Action Plan and NIST’s 2023 AI Risk Management Framework

- Think tank reports, such as from CSET, CNAS, CSIS, and IFP

- ^

The ‘explore–exploit’ dilemma is a decision-making concept about balancing two strategies: exploration (trying new options that might lead to better outcomes) and exploitation (sticking with the best option you know so far). Early career stages are usually best spent exploring — collecting tools and experience first, then doubling down where you think you could have the most impact.

- ^

None of these factors should be definitive for your decision, but they’ll all contribute to how much policy-relevant career capital you’ll gain — which is particularly valuable early in your career. You’ll likely need to consider tradeoffs between them: for example, you might develop stronger skills at a less well-known organisation with better mentorship, or you might build a stronger network at a place with less opportunity for skill development.

- ^

Another highly valuable credential is a security clearance, which makes you more competitive for other cleared roles. Note that the strength of a given credential may vary across policy communities — for instance, some AI policy credentials may be well-recognised within tech policy circles but carry less weight in broader Washington.

- ^

These examples are meant to illustrate how you might reason backwards from the AI issues you find most concerning — not to suggest that these are necessarily the most important issues or policy tools overall. We don’t dive into which threats or interventions should be prioritised in this article, but if you want to explore different risk scenarios and policy approaches in more depth, see these articles.

- ^

Legal authorities mainly come from laws passed by Congress or executive orders (directives from the president).

- ^

Renamed the Department of War (DOW) by executive order in September 2025.

- ^

For instance, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) has convened agencies on AI risk management frameworks and evaluation methods. It didn’t control the funding itself, but by setting the agenda and coordinating across departments, it helped shape how resources were deployed.

- ^

It’s generally straightforward to look up the formal authorities of an office — e.g. what laws, budgets, or regulations it oversees. What’s harder is understanding its soft powers — the influence it has through persuasion, networks, or credibility. Policy roles that give you broad exposure (like congressional staff positions or agency detail assignments) can help you see how the two interact in practice. Even before entering policy, talking with people in the field and following high-quality policy commentary can give you a sense of where informal influence really lies.

- ^

In Washington, people sometimes say an issue is ‘in the water’ — meaning it’s widely circulating in policy conversations, even if it hasn’t yet made it onto the formal agenda.

- ^

Partisan signals can range from big, obvious choices — like interning in a congressional office or donating to a campaign — to smaller ones, such as registering with a party or joining a partisan student group. These signals can open doors within that party but may limit opportunities with the other side, especially in highly vetted roles. The right approach depends on your own beliefs, comfort with partisan affiliation, and long-term goals.

- ^

Civil service roles are formally nonpartisan: you’re hired to serve any administration, regardless of your politics. In practice, agencies have distinct cultures — for example, the Department of State and the Environmental Protection Agency are often seen as more left-leaning, while the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI are seen as more conservative. This contrasts with political appointments, where partisanship is explicit and often vetted for — appointees are chosen specifically to advance an administration’s priorities.

- ^

Political appointees are temporary positions that aren’t typically a first career move unless you’re unusually connected.

- ^

We think the most pivotal policy moments will likely be when systems powerful enough to lock in certain futures are first deployed. Unless you have very short timelines (e.g. you think AGI is fairly likely to be here by 2027 or earlier) and high confidence, it’s often still worth investing in (some) career capital for policy work. The field is still small, and demand for capable people is growing rapidly. Many areas remain neglected, new institutions keep appearing, and there aren’t enough people with both technical and policy expertise. In practice, people more often overestimate how long it takes to become useful in AI policy than the reverse.

- ^

We generally think PhDs aren’t worth the opportunity cost for people interested in policy careers. They can take 6+ years, and the payoff is usually limited outside academia or certain technical niches. That said, a PhD might make sense if you’ve already started, if you do one in the UK (where they take less time), if you’re targeting specific executive branch jobs where PhDs carry weight, or if you’re aiming at research-heavy roles outside US policy.

- ^

These are our best guesses at the time of writing, based on assumptions about which areas of AI policy are likely to matter most. Shifts in politics, the public, or in AI development trajectories could change which institutions are most impactful. Depending on your skills, the highest-impact option might be outside this list entirely — for example, working as a journalist or public writer, at an international organisation, running for office, or working in another policy-relevant role where your background is unusually valuable.

- ^

Even when they can’t directly set policy, presidents bargain constantly — with Congress, agencies, foreign leaders, and the public — to get buy-in for their agendas. As political scientist Richard Neustadt argued: “Presidential power is the power to persuade.”

- ^

Sometimes the president’s proposal is adopted almost wholesale. The tax cuts and spending priorities Trump proposed in spring 2025 became the central framework for Congress’ budget (the One Big Beautiful Bill).

- ^

(The US currently has 48 national emergencies in effect.)

- ^

You must be a US citizen to receive a security clearance. See this guide for a breakdown of US policy roles available to foreign nationals.

- ^

The share of political appointees in the White House is far higher than in federal agencies. Nominees for these positions — about 225 within the EOP and roughly 4,000 across the executive branch — typically have strong networks connecting them to the administration and undergo political vetting. Appointees in the most senior of these roles must also be confirmed by the Senate.

- ^

Career civil service roles are legally required to be nonpartisan, with hiring and advancement based on merit rather than political affiliation. Some analysts argue that recent Trump administration policies introduce elements of political vetting into the hiring processes for these roles.

- ^

The importance of elite credentials varies significantly by administration. Under President Trump’s first term, for example, only 21% of mid- or senior-level staffers had Ivy League degrees.

- ^

- ^

They are: Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, Labor, State, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs. Outside of these departments, there are also many independent agencies — like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), NASA, and the Federal Reserve.

- ^

See budget documents on the National AI Research Institutes program, Department of Energy FY 2024 Budget in Brief, and Department of Defense FY 2024 budget request for uncrewed and autonomous systems. Federal agencies also shape markets through their spending. For some key industries, the government is the largest or only customer. Here, agencies’ decisions on which systems or products to buy (like fighter jets or intelligence software) can make ‘winners and losers’ and shape industry behavior. While this influence may hold less for AI than other industries, it still could matter considerably in areas like defense AI, cybersecurity, and government cloud services where federal contracts can determine market leaders.

- ^

For cleared roles, aim to apply at least nine months before your target start date.

- ^

We’re cheating a bit here — the intelligence community isn’t technically a department but rather a network of 18 agencies and military services across the executive branch. They’re responsible for collecting, analysing, and delivering intelligence to senior US leaders to inform national security decisions.

- ^

In practice, presidents often test the boundaries of their powers. For example, while only Congress can declare war, presidents have repeatedly launched major military actions without formal declarations, citing their role as Commander-in-Chief or relying on broad congressional Authorizations for Use of Military Force (AUMFs). They’ve also used executive orders to create new offices or shift responsibilities within agencies — moves that reshape how the federal government operates even though they can’t legally create or abolish agencies without Congress. This gradual expansion of presidential authority has led some scholars to describe the modern presidency as ‘imperial.’

- ^

This is especially true in the House, where members are up for reelection every two years (and may spend huge portions of their time fundraising or campaigning). Some factors — like being in an electorally ‘unsafe’ district or having constituents who care a lot about a particular issue — can intensify these electoral pressures.

- ^

Some describe this as the divide between ‘show horses,’ who focus on visibility and messaging, and ‘workhorses,’ who quietly draft and pass substantive legislation. One congressional staffer noted the shift toward the former: “In Congress today, we have a sea of show horses, all cultivating their public personas, polishing off their Twitter chops, doing things to capture the conservative or progressive zeitgeist of the moment, the more outrageous the better … The bread-and-butter of the legislative process, constructing complicated deals among competing special interests, crafting agreements among industries and setting the rules of the road for economic progress, has been derailed by intense political partisanship.”

- ^

Journalist Robert Kaiser observed that committee staffers can have more influence on the substance of legislation than committee members themselves.

- ^

‘All else equal’ does a lot of work here. An influential member can outweigh an entire committee, and a highly effective House member could make a much bigger impact than some senators. Where you’ll have the most impact depends heavily on your own fit, timing, and the specific opportunities on offer.

- ^

Congress can be surprisingly insular. Members are hard to pin down without strong relationships, and staffers are often overextended and hard to reach. Unless you’re directly on the Hill, have a well-cultivated network, or work in an advocacy group whose job is engaging Congress, it can be difficult to exert influence here in a focused way.

- ^

This assumes that Congress is paying your salary: some congressional fellowships like Horizon, AAAS, and TechCongress pay fellows’ salaries during their placement.

- ^

We list committees rather than individual members because members can turn over after their term, and committee work is often more impactful. That said, working for the offices of certain individual members can be more impactful than working for the committees themselves. One way to choose which member to work for is to look at which committees they serve on.

- ^

See which states proposed which AI policies in 2025 here.

- ^

- ^

California’s Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (SB 53) is the nation’s first major state-level AI safety law. It combines transparency rules, a new public research cluster, whistleblower protections, and recommended annual updates — aiming to set a model for federal legislation in a space where Congress has yet to act.

- ^

The ‘California Effect’ is the best-known example: California’s tougher vehicle emissions standards in the 1960s, and more recently its AI safety legislation, have prompted companies to follow those rules nationwide and inspired action in other states and in Congress.

- ^

This is called preemption. The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause makes federal law the “supreme law of the land,” but Congress can only preempt in areas where it has constitutional authority — usually things that cross state lines, like immigration, foreign affairs, interstate commerce, or national defense.

- ^

In May 2025, the House passed a budget bill that included a 10-year ban (a “moratorium”) on state AI laws. When the bill reached the Senate, Senators proposed a narrower version that tied about $500 million in federal broadband funds to states agreeing not to pass new AI regulations. The Senate ultimately rejected that approach in a 99–1 vote, removing the moratorium entirely.

- ^

States vary widely in how their legislatures operate. ‘Professional’ legislatures like California’s or New York’s meet year-round and employ permanent staff, while ‘citizen’ or part-time legislatures (such as Texas or Montana) often convene only part of the year and rely heavily on temporary or ‘session-only’ staff.

- ^

For example, California’s SB 53 requires AI labs to report major incidents to the California Office of Emergency Services.

- ^

For example, the Heritage Foundation (right-leaning) and the Center for American Progress (left-leaning) ride this line: they publish policy analysis but also actively campaign for preferred outcomes. Legally, the distinction often comes down to tax status. Most think tanks are 501(c)(3) nonprofits — educational and charitable organisations that can receive tax-deductible donations but have strict limits on lobbying and election-related work. 501(c)(4) ‘social welfare’ groups, by contrast, can spend more time directly lobbying or supporting specific policies and politicians, and their donations aren’t tax-deductible. Many groups operate both arms — a (c)(3) for research and education and a (c)(4) for lobbying.

- ^

We don’t go into detail about these think tanks here, but if you are weighing think tanks to pursue and want more depth, apply to speak with us – we may be able to put you in touch with experts who will have up to date views on the field. Note that in many ways, think tanks are the hardest of the five policy institutions to predict impact for: they lack formal authority, and their influence can shift dramatically with political conditions, funding, and relationships. Also, some policy-adjacent organisations don’t fit neatly into either ‘think tank’ or ‘advocacy’ categories — for example, Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) and Epoch AI focus on policy-relevant technical evaluations and forecasting. Similarly, organisations like the Centre for the Governance of AI (GovAI), the Institute for AI Policy and Strategy (IAPS), and the Institute for Law & AI (LawAI) aren’t traditional DC think tanks, but they produce policy-relevant research and cultivate talent.

SummaryBot @ 2026-02-11T17:30 (+2)

Executive summary: This guide argues that the US government is a pivotal actor in shaping advanced AI and outlines heuristics and specific institutions — especially the White House, key federal agencies, Congress, major states, and influential think tanks — where working could plausibly yield outsized impact on reducing catastrophic AI risks, depending heavily on timing and personal fit.

Key points:

- The authors propose five heuristics for impact: build career capital early, work backward from the most important AI issues, prioritize institutions with meaningful formal or informal power, prepare for unpredictable “policy windows,” and choose roles that fit your strengths.

- They argue that early-career professionals should avoid narrow AI specialization if it sacrifices networks, tacit knowledge, credentials, and broadly valued policy skills.

- The guide suggests reasoning from specific AI risk concerns (e.g., catastrophic misuse, geopolitical conflict, AI takeover) to particular policy levers such as liability rules, export controls, safety evaluations, and R&D funding.

- The Executive Office of the President is presented as especially impactful because of its agenda-setting power, budget proposals, foreign policy authority, and ability to act quickly in crises, despite institutional constraints and political turnover.

- Federal agencies, Congress (especially key committees and majority-party roles), and major states like California are described as powerful because they control budgets, implement and interpret laws, regulate industry, and can set de facto national standards.

- Think tanks and advocacy organizations are portrayed as influential through research, narrative-shaping, lobbying, and talent pipelines into government, though their policy impact is characterized as “lumpy” and less predictable.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Tony Rost @ 2026-02-10T23:26 (+1)

This is a great guide and I appreciate the work. Thank you!

Please consider adding the bans on AI consciousness/sentience/self-awareness. There are several laws in flight: https://harderproblem.fund/legislation/

The issue here is that these laws go beyond liability topics with personhood, and instead could choke future discussions about potential welfare issues. They simply go too far, and are too sticky.