Things usually end slowly

By OllieBase @ 2022-06-07T17:00 (+76)

Epistemic status: Low confidence. These findings updated me slightly towards worrying more about slow declines vs. sudden collapse/extinction. Most sources are things I quickly googled so are probably off the mark.

TL;DR It’s sometimes claimed or suggested that if an extinction event were to happen, it would happen very quickly (i.e. days, weeks, months). However, when empires fall or species go extinct, they usually do so very slowly (years, decades, millennia). These base rates[1] suggest we should have a reasonably strong prior on slow decline when thinking about civilisational collapse and, at more of a stretch, existential risks. This sketch is very rough, and I’d love to see someone work out these base rates, and how they might be changing, more carefully.

Rapid extinction

Thinkers in and around the EA community sometimes claim that x-risk scenarios will cause extinction rapidly. For example:

- Eliezer Yudkowsky argues that the likely scenario with AGI takeoff is “growth stays at 5%/year and then everybody falls over dead in 3 seconds and the world gets transformed into paperclips”

- Toby Ord, in The Precipice (p.28), writes that “As technology continues to advance, new threats appear on the horizon. These threats promise to be more like nuclear weapons than like climate change: resulting from sudden breakthroughs, precipitous catastrophes”

- Relatedly, the metaphor of a precipice implies a very steep descent from stability to extinction.[2]

Perhaps it’s right to expect that an existential catastrophe will be rapid. Your inside view might well take into account things happening awfully fast (such as rapidly increasing compute efficiency or pathogens spreading). But holding this view should require a very strong update from the prior that extinction events and civilisational collapses usually take a very long time.

Data from civilisations

Two caveats:

- I expect the way I’m most likely to be wrong about all this is that historical extinctions and civilisational collapses are not appropriate reference classes for x-risks. I think they’re very useful because they’re a rough approximation of x-risks from actual data and I’m sceptical of claims along the lines of “the thing I’m worried about is totally unique ”, but I could be wrong.

- While we often refer to the “fall” of Rome and the “collapse” of the Mayans, it’s rarely appropriate to consider human empires and civilisations extinct. In this post, I usually use years when the empire or civilisation is considered by scholars to have “ended.” The specific year, or whether they “ended” at all, is usually up for debate.

To form a rough prior on how long things (civilisations, empires, species) take to decline, I scanned some encyclopedic pages to find:

- The start of the end: the last period in time when the civilisation was still ‘flourishing’, usually just before the start of a collapse or invasion.[3]

- The earliest plausible date and the latest plausible date which could constitute the “end” of the civilization, to form a kind of confidence interval.

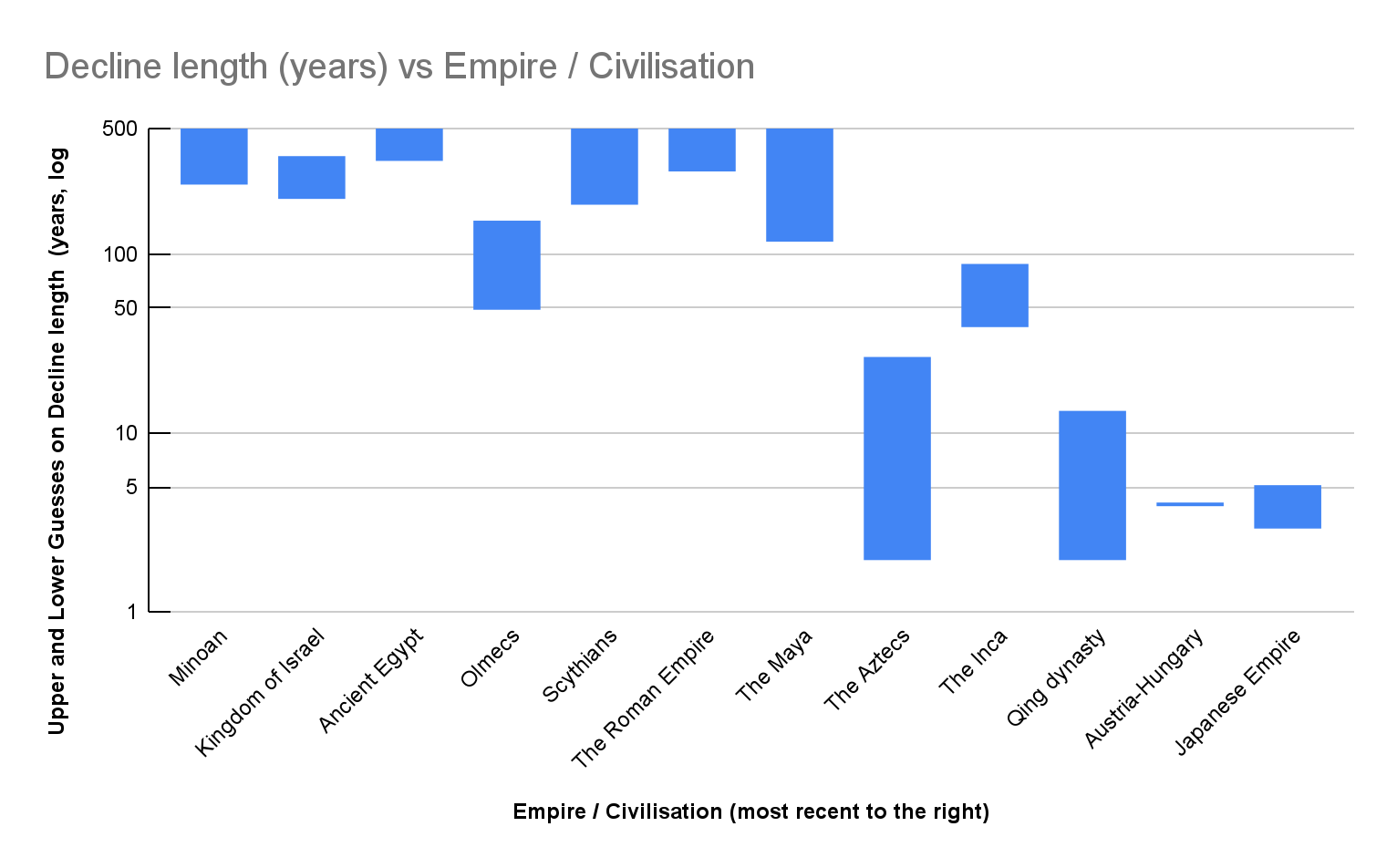

This sheet lists some empires, their last points of flourishing, their earliest reasonable dissolution points and their latest reasonable dissolution points. From this, I calculated a lower guess on decline length and an upper guess on decline length (in years). You can see this summary graph below. I expect anyone could review these dates and find points of disagreement, even by reviewing the same sources I did. Furthermore, I’d love to see someone expand this list (perhaps using this useful list compiled by Luke Kemp).

You don’t need to read this data too carefully to notice that rapid dissolution is clearly the exception to the rule.

One interesting thing to note, however, is that declines do seem to be happening faster over time. The data is certainly weak but the trend is also relatively clear.

Why is this? Here are some hypotheses (some of which overlap):[4]

- Empires and nation states are interacting with each other more and more over time.

- Economic growth is accelerating, and this allows challengers to rise much more quickly and defeat the incumbent empire more quickly.

- Many empires end when conquered, and wars happen much more quickly now (I’m not sure why - maybe because planes are faster than walking?)

- The "fitness landscape" of empires changes faster due to accelerating global cultural and technological changes.

Data from species

An obvious response to claims based on the above dataset is that these are all civilizations that are part of humanity and that we should think very differently about humanity itself. But we do have evidence for how long species extinction events usually take.

There have been 5 major extinction events in history, where mass extinction is defined as over 70% of species going extinct (from Our World in Data’s excellent resource on this):

Extinction Event | Age (mya) | % of species lost | Cause of extinction | Approx. length of decline |

End Ordovician | 444 | 86% | Intense glacial and interglacial periods created large swings in sea levels and moved shorelines dramatically. Tectonic uplift of the Appalachian mountains created lots of weathering, sequestration of CO2 and with it, changes in climate and ocean chemistry. | ~30 million years |

Late Devonian | 360 | 75% | Rapid growth and diversification of land plants generated rapid and severe global cooling. | 500,000 to 25 million years |

End Permian | 250 | 96% | Intense volcanic activity in Siberia. This caused global warming. Elevated CO2 and sulphur (H2S) levels from volcanoes caused ocean acidification, acid rain, and other changes in ocean and land chemistry. | 200,000 to 15 million years |

End Triassic | 200 | 80% | Underwater volcanic activity in the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) caused global warming, and a dramatic change in chemistry composition in the oceans. | <10,000 years |

End Cretaceous | 65 | 76% | Asteroid impact in Yucatán, Mexico. This caused global cataclysm and rapid cooling. Some changes may have already pre-dated this asteroid, with intense volcanic activity and tectonic uplift. | 1,000 to 71,000 years |

You’ll often see the causes of these extinction events described as “rapid” or “sudden” but it’s worth putting these numbers in context (even the term “event” is somewhat confusing). Most of these mass extinctions occurred over a timescale of over a million years, with some claims of more “rapid” extinction events lasting tens of thousands of years.

- E-O: A series of extinctions that took place over 30 million years (445 to 415 million years ago).

- L-D: Estimates range from 500,000 to 25 million years, extending from the mid-Givetian to the end-Famennian. Some consider the extinction to be as many as seven distinct events, spread over about 25 million years.

- E-P: Quoting from Brittanica: “Many geologists and palaeontologists contend that the Permian extinction occurred over the course of 15 million years during the latter part of the Permian Period (299 million to 252 million years ago). However, others claim that the extinction interval was much more rapid, lasting only about 200,000 years, with the bulk of the species loss occurring over a 20,000-year span near the end of the period.”

- E-T: Less than 10,000 years.

- E-C: Some evidence suggests extinction over a period of less than 10,000 years. Other evidence points to a duration of 1,000 - 71,000 years. Of course, many species were probably killed within a few years of the impact (perhaps instantly) - I didn’t look into this.

- At the current rate of species extinction, which is extremely fast in historical terms, it would take us 37,500 years to lose 75%.

Some of the shortest estimates for the length of these extinction events are still longer than the entire history of humanity (~200,000 years).

Of course, this is for 75% of species on Earth, and we’re just one. I struggled to find an authoritative source for the time it takes for individual species to decline. Some data points:

- The Neanderthals peaked in population around 52,000 years ago, before disappearing around 28,000 to 35,000 years ago with the arrival in Europe of Homo sapiens - a decline of 17,000 - 24,000 years.

- More recently, The Pinta Island tortoise was first encountered[5] and hunted in 1877 and was classified as extinct in 2012 (spare a thought for the last surviving male, Lonesome George) - a decline of >100 years.

- Schomburgk's deer was first encountered in 1863 and the last captive individual was killed in 1938 - a decline of 75 years.

- The Desert rat-kangaroo was first encountered in the early 1840s. It was last sighted in 1935 and first pronounced extinct in 1994 - a decline of 100 - 160 years.

I pulled the last three examples from the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species’ Extinction list - it would be cool if someone built a better dataset of how long extinctions usually take from this list.

Why we might not trust the data from species

It’s hard to draw conclusions from the data on species’ extinction, and the uncertainties do not pull in favour of a prior on very slow decline:[6]

- We won’t notice rapid declines in fossil records. The base rates on the length of decline we can get from the fossil record must have a high lower bound since we just don't have that many fossils and the time granularity is poor. If species were rising and falling at a rate of years or months, this wouldn't show up in the fossil record.

- For mass extinctions, it may take a long time for the total number of extinctions to creep up because not all species become maladapted at once. We should probably expect a large number of individual species to die out quite rapidly over the course of a mass extinction event (e.g. due to an asteroid).

- This data can help us form a prior on the length of climate-induced catastrophes and natural extinction events (e.g. asteroids) but not the anthropological threats that we face today.

This doesn’t cause me to totally ignore the data here - species do seem to die out slowly - but we should take all the data here with a very big pinch of salt.

Takeaway

Before we look at potential x-risk scenarios, base rates suggest we should have a reasonably strong prior on extinction events occurring very slowly - over years, decades and millennia rather than days, weeks and months.

More specifically, it seems that mass extinctions from natural causes tend to occur over the course of millennia while civilisational collapses brought on by anthropogenic causes tend to occur over the course of years, decades and centuries. We should want to see very strong evidence that extinction events might happen faster than this to update towards something like a days, weeks and months expectation.

There might be some more interesting takeaways here. Perhaps this should give us some hope that we can notice the beginning of an existential decline and prevent it, or that we should look harder for signs of slow decline to protect ourselves against. However, I’m not confident enough in the data or the argument to make such claims.

And to reiterate, this sketch is very rough. I’d love to see someone work out this base rate, and how it might be changing, more carefully.

My thanks to Luisa Rodriguez, Lizka Vaintrob, Sophie Rose, Stephen Clare, Matthew van der Merwe and Justis Mills for comments and encouragement.

- ^

Careful readers will note it’s actually very funny I’m discussing base rates, because it is the name of my blog which is named after me.

- ^

Look out for my forthcoming book on this topic, “The Concerningly Steep Slope”.

- ^

This is probably the most ill-defined part of the analysis, but there is lots of competition for this title.

- ^

My thanks to Stephen Clare, who suggested most of these.

- ^

Note that, for many individual species, the first observation of a species is, sadly, also the point at which the discoverers start hunting it to extinction.

- ^

My thanks to Matthew van der Merwe and Stephen Clare for pointing these out.

John G. Halstead @ 2022-06-07T18:03 (+45)

Thanks for this Ollie. As you allude to in your post, I think the problem with this is that past collapses of empires and civilisations or extinctions of species are not an appropriate reference class for technological risks from AI, bio and nuclear weapons. I think this shows that the typical things that local civilisations faced prior to 1950 tended to cause relatively slow collapse. But the risks that we seem to face this century are entirely novel - the destructive power of the tools at our disposal today is orders of magnitude greater than the tools that the Romans had. We should therefore expect collapse to happen much more quickly. eg We just couldn't vaporise entire cities until 1945.

Nathan Young @ 2022-06-09T11:49 (+13)

To add to this, we now know that most slow collapse probably won't kill us all. We are much more capable of adapting and surviving as a species than the reference class. This leaves disatsters which are too strategic or quick for us to adapt to. Most of that class seems to be rapid.

OllieBase @ 2022-06-13T09:54 (+1)

Thanks, John! Helpful to see that you think my best guess of why I might be wrong might be right.

Charles He @ 2022-06-07T17:12 (+18)

Unfortunately, I think falling empires and species decline is a different mechanism of decline than many AI risk models.

If you give credence to “foom”, “ASI/AGI” these do involve almost immediate and total destruction or permanent loss of agency.

A closer analogy or model might be nuclear weapons? (Although they don’t result in total destruction).

These ideas seem highly relevant slow takeoff and maybe related lock-in and multipolar conflict. These aren’t talked about much (but are anyways probably conjunctive with most “AI safety interventions”?, besides yelling we are all doomed).

Mauricio @ 2022-06-08T00:50 (+12)

As an additional potential analogy, some scenarios people discuss seem analogous to coups. If that's a good analogy, I think it suggests that things would be quick.

Stephen Clare @ 2022-06-08T10:40 (+5)

Nice work Ollie, this is very thought-provoking. It got me thinking a lot more about plausible reference classes for human extinction.

As I've mentioned to you, I think individual species extinctions are a better reference class than mass extinction events. It's a shame you couldn't find a good source that summarizes how quickly species declines tend to happen. Individual species must end faster than extinction events, since species collapses all occur within extinction events. And I strongly suspect if we had data on them, we'd see that species tend to go extinct much faster than extinction events. There's selection bias at work, but I can recall seeing graphs of, e.g., global whale, elephant, and rhinocerous populations that show precipitous declines following an exogenous catastrophe (usually the introduction of humans, or the invention of a new technology like whaling ships).

Your discussion of civilizational decline timelines, on the other hand, does seem directly relevant. It would be great to see a database that tracks the duration of civilizational declines categorized by cause (where possible), to see if we can find more specific reference classes based on different risks!

OllieBase @ 2022-06-13T09:58 (+2)

Thanks, Stephen! Yeah, excited to see more data in this space, all over the place.

Chris Leong @ 2022-06-07T18:14 (+4)

Somewhat echoing others, I think a better reference class is looking at the ability of human technology to cause damage over time and that seems to have increased, quite dramatically.

I'd suggest that an interesting question to ask would be: "If things end slowly, how similar are the reasons for this likely to for previous civilisations?". I think would be much easier to extract out these specific reasons and to try to show that one or more of them is analogous to our current situation.

And to reiterate, this sketch is very rough. I’d love to see someone work out this base rate, and how it might be changing, more carefully.

Perhaps, although working this out in more detail doesn't seem, at least to my mind, to be the right focus for future work. Instead, I'd suggest developing the line I suggest above.

OllieBase @ 2022-06-13T09:59 (+1)

That does sound like a better reference class and question, thanks!

Stephen Clare @ 2022-06-08T10:43 (+3)

wars happen much more quickly now (I’m not sure why - maybe because planes are faster than walking?)

I think advances in strategy, automation, logistics, and transportation have a lot to do with this! And I do think there's a general lesson there - everything has been speeding up, so we should generally expect collapses today to happen faster than they happened in the past.

Jackson Wagner @ 2022-06-07T22:09 (+3)

Other commenters are arguing that next time things might be different, due to the nature of technological risks like AI. I agree, but I think there's an even simpler reason to focus attention on rapid-extinction scenarios: we don't have as much time to prevent them!

If we were equally worried about extinction due to AI, versus extinction due to slow economic stagnation / declining birthrates / political decay / etc, we might still want to put most of our effort into solving AI. As they say, "there's a lot of ruin in an empire" -- if human civilization was on track to dwindle away over centuries, that also means we'd have centuries to try and turn things around.

OllieBase @ 2022-06-13T10:00 (+1)

This is a good point, thanks!

HaydnBelfield @ 2022-06-07T22:42 (+1)

Great post! Mass extinctions and historical societal collapses are important data sources - I would also suggest ecological regime shifts. My main takeaway is actually about multicausality: several ‘external’ shocks typically occur in a similar period. ‘Internal’ factors matter too - very similar shocks can affect societies very differently depending on their internal structure and leadership. When complex adaptive systems shift equilibria, several causes are normally at play.

Myself, Luke Kemp and Anders Sandberg (and many others!) have three seperate chapters touching on these topics in a forthcoming book on 'Historical Systemic Collapse' edited by Princeton's Miguel Centeno et al . Hopefully coming out this year.

OllieBase @ 2022-06-13T09:57 (+1)

Thanks Haydn! I didn't totally follow this since I'm not familiar with some of these terms, but great to hear that some more thorough literature surrounding this!