The perils of maximising the good that you do (Toby Ord on the 80,000 Hours Podcast)

By 80000_Hours @ 2023-09-14T12:14 (+12)

We just published an interview: Toby Ord on the perils of maximising the good that you do. You can click through for the audio, a full transcript, and related links. Below are the episode summary and some key excerpts.

Episode summary

One thing that you can say in general with moral philosophy is that the more extreme theories which are less in keeping with all of our current moral beliefs — are also less likely to encode the prejudices of our times. We say in the philosophy business that they’ve got more “reformative power” … But that comes with the risk that we will end up doing things that are … intuitively bad or wrong — and that they might actually be bad or wrong. So it’s a double-edged sword… and one would have to be very careful when following theories like that.

- Toby Ord

Effective altruism is associated with the slogan “do the most good.” On one level, this has to be unobjectionable: What could be bad about helping people more and more?

But in today’s interview, Toby Ord — moral philosopher at the University of Oxford and one of the founding figures of effective altruism — lays out three reasons to be cautious about the idea of maximising the good that you do. He suggests that rather than “doing the most good that we can,” perhaps we should be happy with a more modest and manageable goal: “doing most of the good that we can.”

Toby was inspired to revisit these ideas by the possibility that Sam Bankman-Fried, who stands accused of committing severe fraud as CEO of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, was motivated to break the law by a desire to give away as much money as possible to worthy causes.

Toby’s top reason not to fully maximise is the following: if the goal you’re aiming at is subtly wrong or incomplete, then going all the way towards maximising it will usually cause you to start doing some very harmful things.

This result can be shown mathematically, but can also be made intuitive, and may explain why we feel instinctively wary of going “all-in” on any idea, or goal, or way of living — even something as benign as helping other people as much as possible.

Toby gives the example of someone pursuing a career as a professional swimmer. Initially, as our swimmer takes their training and performance more seriously, they adjust their diet, hire a better trainer, and pay more attention to their technique. While swimming is the main focus of their life, they feel fit and healthy and also enjoy other aspects of their life as well — family, friends, and personal projects.

But if they decide to increase their commitment further and really go all-in on their swimming career, holding back nothing back, then this picture can radically change. Their effort was already substantial, so how can they shave those final few seconds off their racing time? The only remaining options are those which were so costly they were loath to consider them before.

To eke out those final gains — and go from 80% effort to 100% — our swimmer must sacrifice other hobbies, deprioritise their relationships, neglect their career, ignore food preferences, accept a higher risk of injury, and maybe even consider using steroids.

Now, if maximising one’s speed at swimming really were the only goal they ought to be pursuing, there’d be no problem with this. But if it’s the wrong goal, or only one of many things they should be aiming for, then the outcome is disastrous. In going from 80% to 100% effort, their swimming speed was only increased by a tiny amount, while everything else they were accomplishing dropped off a cliff.

The bottom line is simple: a dash of moderation makes you much more robust to uncertainty and error.

As Toby notes, this is similar to the observation that a sufficiently capable superintelligent AI, given any one goal, would ruin the world if it maximised it to the exclusion of everything else. And it follows a similar pattern to performance falling off a cliff when a statistical model is ‘overfit’ to its data.

In the full interview, Toby also explains the “moral trade” argument against pursuing narrow goals at the expense of everything else, and how consequentialism changes if you judge not just outcomes or acts, but everything according to its impacts on the world.

Toby and Rob also discuss:

- The rise and fall of FTX and some of its impacts

- What Toby hoped effective altruism would and wouldn’t become when he helped to get it off the ground

- What utilitarianism has going for it, and what’s wrong with it in Toby’s view

- How to mathematically model the importance of personal integrity

- Which AI labs Toby thinks have been acting more responsibly than others

- How having a young child affects Toby’s feelings about AI risk

- Whether infinities present a fundamental problem for any theory of ethics that aspire to be fully impartial

- How Toby ended up being the source of the highest quality images of the Earth from space

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type ‘80,000 Hours’ into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript.

Producer and editor: Keiran Harris

Audio Engineering Lead: Ben Cordell

Technical editing: Simon Monsour

Transcriptions: Katy Moore

Highlights

Maximisation is perilous

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So what goes wrong when you try to go from doing most of the good that you can, to trying to do the absolute maximum?

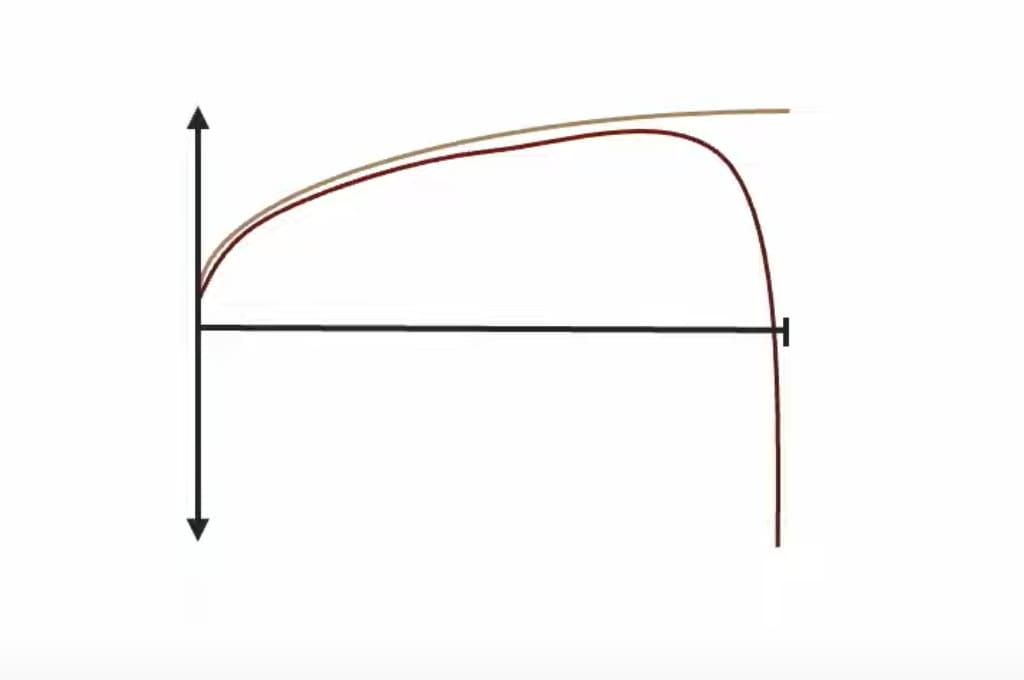

Toby Ord: Here’s how I think of it. Even on, let’s say, utilitarianism, if you try to do that, you generally get diminishing returns. So you could imagine trying to ramp up the amount of optimising that you’re doing from 0% to 100%. And as you do so, the value that you can create starts going up pretty steeply at the start, but then it starts tapering off as you’ve used up a lot of the best opportunities, and there’s fewer things that you’re actually able to bring to bear in order to help improve the situation. As you get towards the end, you’ve already used up the good opportunities.

But then it gets even worse when you consider other moral theories — if you’ve got moral uncertainty, as I think you should — and you also have some credence that maybe there are some other things that fundamentally matter apart from happiness or whatever theory that you like most says. There are these tradeoffs as you optimise for the main thing; there can be these tradeoffs to these other components that get steeper and steeper as you get further along.

So maybe, suppose as well as happiness, it also matters how much you achieve in your life or something like that. Then it may be that many of the ways that you can improve happiness, let’s say in this case, involve achievements — perhaps achievements in terms of charity, and achievements in terms of going out in the world and accomplishing stuff. But as you get further, you can start to get these tradeoffs between the two, and it can be the case for this other thing that it starts going down. If instead we were comparing happiness first and then freedom, maybe the ways that you could create the most happiness involve, when you try to crank up that optimisation right to 100%, just giving up everything else if need be. So maybe there could be massive sacrifices in terms of freedom or other things right at the end there.

And perhaps a real-world example to make that concrete is if you think about, say, trying to become a good athlete: maybe you’ve taken up running, and you want to get faster and faster times, and achieve well in that. As you start doing more running, your fitness goes up and you’re also feeling pretty good about it. You’ve got a new exciting mission in your life. You can see your times going down, and it makes you happy and excited. And so a lot of metrics are going up at the start, but then if you keep pushing it and you make running faster times the only thing you care about, and you’re willing to give up anything in order to get that faster time, then you may well get the absolute optimum. Of all the lives that you could live, if you only care about the life that has the best running time, it may be that you end up making massive sacrifices in relationships, or career, or in that case, helping people.

So you can see that it’s a generic concept. I think that the reason it comes up is that we’ve got all of these different opportunities for improving this metric that we care about, and we sort them in some kind of order from the ones that give you the biggest bang for their buck through to the ones that give you the least. And in doing so, at the end of that list, there are some ones that just give you a very marginal benefit but absolutely trash a whole lot of other metrics of your life. So if you’re only tracking that one thing, if you go all the way to those very final options, while it does make your primary metric go up, it can make these other ones that you weren’t tracking go down steeply.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, so the basic idea is if there’s multiple different things that you care about… So we’ll talk about happiness in life versus everything else that you care about — having good relationships, achieving things, helping others, say. Early on, when you think, “How can I be happier?,” you take the low-hanging fruit: you do things that make you happier in some sensible way that don’t come at massive cost to the rest of your life. And why is it that when you go from trying to achieve 90% of the happiness that you could possibly have to 100%, it comes at this massive cost to everything else? It’s because those are the things that you were most loath to do: to just give up your job and start taking heroin all the time. That was extremely unappealing, and you wouldn’t do it unless you were absolutely only focused on happiness, because you’re giving up such an incredible amount.

Toby Ord: Exactly. And this is closely related to the problem with targets in government, where you pick a couple of things, like hospital waiting times, and you target that. And at first, the target does a pretty good job. But when you’re really just sacrificing everything else, such as quality of care, in order to get those people through the waiting room as quickly as possible, then actually you’re shooting yourself in the foot with this target.

And the same kind of issue is one of the arguments for risk from AI, if we try to include a lot of things into what the AI would want to optimise. And maybe we hope we’ve got everything that matters in there. We better be right, because if we’re not, and there’s something that mattered that we left out, or that we’ve got the balance between those things wrong, then as it completely optimises, things could move from, “The system’s working well; everything’s getting better and better” to “Things have gone catastrophically badly.”

I think Holden Karnofsky used this term “maximization is perilous.” I like that. I think that captures both what’s one of these big problems if you have an AI agent that is maximising something, and if you have a human agent — perhaps a friend or you yourself — who is just maximising one thing. Whereas if you just ease off a little bit on the maximising, then you’ve got a strategy that’s much more robust.

How moral uncertainty protects against the perils of utilitarianism

Toby Ord: One thing that you can say in general with moral philosophy is that the more extreme theories — which are, say, less in keeping with all of our current moral beliefs — are also less likely to encode the prejudices of our times. So what we say in the philosophy business is that they’ve got more “reformative power”: they’ve got more ability to actually take us somewhere new and better than where we currently are. Like if we’ve currently got moral blinkers on, and there’s some group who we’re not paying proper attention to and their plight, then a theory with reformative power might be able to help us actually make moral progress. But it comes with the risk that by having more clashes with our intuitions, we will end up perhaps doing things that are more often intuitively bad or wrong — and that they might actually be bad or wrong. So it’s a double-edged sword in this area, and one would have to be very careful when following theories like that.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So you say in your talk that for these reasons, among others, you couldn’t embrace utilitarianism, but you nonetheless thought that there were some valuable parts of it. Basically, there are some parts of utilitarianism that are appealing and good, and other parts about which you are extremely wary. And I guess in your vision, effective altruism was meant to take the good and leave the bad, more or less. Can you explain that?

Toby Ord: Yeah, I certainly wouldn’t call myself a utilitarian, and I don’t think that I am. But I think there’s a lot to admire in it as a moral theory. And I think that a bunch of utilitarians, such as John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, had a lot of great ideas that really helped move society forwards. But in part of my studies — in fact, what I did after all of this — was to start looking at something called moral uncertainty, where you take seriously that we don’t know which of these moral theories, if any, is the right way to act.

And that in some of these cases, if you’ve got a bit of doubt about it… you know, it might tell you to do something: a classic example is if it tells the surgeon to kill one patient in order to transplant their organs into five other patients. In practice, the utilitarians tend to argue that actually the negative consequences of doing that would actually make it not worth doing. But in any event, let’s suppose there was some situation like that, where it suggested that you do it and you couldn’t see a good reason not to. If you’re wrong about utilitarianism, then you’re probably doing something really badly wrong. Or another example would be, say, killing a million people to save a million and one people. Utilitarianism might say, well, it’s just plus one. That’s just like saving a life. Whereas every other theory would say this is absolutely terrible.

The idea with moral uncertainty is that you hedge against that, and in some manner — up for debate as to how you do it — you consider a bunch of different moral theories or moral principles, and then you think about how convinced you are by each of them, and then you try to look at how they each apply to the situation at hand and work out some kind of best compromise between them. And the simplest view is just pick the theory that you’ve got the highest credence in and just do whatever it says. But most people who’ve thought about this don’t endorse that, and they think you’ve got to do something more complicated where you have to, in some ways, mix them together in the case at hand.

And so while I think that there is a lot going for utilitarianism, I think that on some of these most unintuitive cases, they’re the cases where I trust it least, and they’re also the cases where I think that the other theories that I have some confidence in would say that it’s going deeply wrong. And so I would actually just never be tempted in doing those things.

It’s interesting, actually. Before I thought about moral uncertainty, I thought, if I think utilitarianism is a pretty good theory, even if I feel like I shouldn’t do those things, my theory is telling me I have to. Something along those lines, and there’s this weird conflict. Whereas it’s actually quite a relief to have this additional humility of, well, hang on a second, I don’t know which theory is right. No one does. And so if the theory would tell you to really go out on a limb and do something that could well be terrible, actually, a more sober analysis suggests don’t do that.

The right decision process for doing the most good

Toby Ord: Many people think that utilitarianism tells us, when we’re making decisions, to sit there and calculate, for each of the possible options available to you, how much happiness it’s going to create — and then to pick the one that leads to the best outcome. Now, if you haven’t encountered this before, you may think that’s exactly what I said earlier that utilitarianism is, but I hope I didn’t make this mistake back then, and I think I probably got it right.

So naive utilitarianism is treating the standard of what leads to the best happiness as a decision procedure: it’s saying that the way we should make our decisions is in virtue of that. Whereas what utilitarianism says is that it’s a criterion of rightness for different actions — so it’s kind of the gold standard, the ultimate arbiter of whether you did act rightly or wrongly — but it may be that in attempting to do it, you systematically fail.

And this can be made clear through something called the “paradox of hedonism”: where, even just in your own life, suppose you think that having more happiness makes your life go better, and so you’re always trying to have more happiness. And so every day when you get up you’re like, “What would make me happy today?” And then you think, “Which of these breakfast cereals would make me happiest?” And then you’re having it and you’re like, “Would chewing it slower make me happier?” And so on. Well, you’re probably going to end up with less happiness than if you were just doing things a bit more normally. And it’s not really a paradox; it’s just that constantly thinking about some particular standard is not always the best way to achieve it.

And that was known to the early utilitarians. In fact, they wrote about this quite eloquently. They suggested that there could be other decision procedures which are better ways of making our decisions. So it could be that even on utilitarian standards, more happiness would be created if we made our decisions in some other way. Perhaps if we are trying this naive approach of always calculating what would be best, our biases will creep in, and so we’ll tend to distribute benefits to people like us instead of to those perhaps who actually would need it more. Indeed, there is a lot of opportunity for that, including your self-serving biases. You might think, “Actually, that nice thing that my friend has would create more happiness if I had it, and so I’m just going to swipe it on the way out the door.”

The concern is that actually there is quite a lot of this self-regarding and in-group bias with people, and so if they were all trying to directly apply this criterion and to treat it as a decision procedure, they probably would do worse than they would do under some other methods. And for a thoroughgoing utilitarian, the best decision procedure is whichever one would lead to the most happiness. If that turns out to be to make my decisions like a Kantian would, if that really would lead to more of what I value, then fine, I don’t have a problem with it.

And so one thing that’s quite interesting is that utilitarianism, in some sense, is in less conflict than people might think with other moral theories, because the other moral theories are normally trying to provide a way of making the decisions. Whereas utilitarianism is potentially open to agreeing with them about their way of making decisions, if that could be grounded in the idea that it produces more happiness.

Moral trade

Toby Ord: Suppose you’re completely certain, and you think only happiness matters. So you’re not worried about the moral uncertainty case, and you’re not worried about this idea that other things might go down in that last 1% of optimisation, because you think this really is the only thing that matters.

Well, at least if you’re interested in effective altruism, then you’re part of a movement that involves people who care about other things, and you’re trying to work with them towards helping the world. And so this last bit of optimisation that you’re doing would be very uncooperative with the other people who are part of that movement.

So this can be connected to a broader idea that I’ve written about called moral trade, where the idea is that, just as people often exchange goods or services in order to make both of them better off — this is the idea that Adam Smith talked about: if you pay the baker for some bread, you’re making this exchange because you both think that you’re better off with the thing the other person had — you could do that not just about your self-interested preferences, but with your moral preferences. And in fact, the theory of trade works equally well in that context.

For example, suppose there were two friends, one of whom used to be a vegetarian but had stopped doing it because maybe they got disillusioned with some of the arguments about it. But they’d kind of gone off meat to some degree anyway, and so it wouldn’t be too much of a burden if they went back to being a vegetarian. That person cares a lot about global poverty, and their friend cares about factory farming and vegetarianism. Well, they could potentially make a deal and say, “If you go back to being a vegetarian, I will donate to this charity that you keep telling me about.” They might each not be quite willing to do that on their own moral views, but to think that if the other person changed their behaviour as well, that the world really would be better off.

And you can even get cases where they’ve got diametrically opposed views. Perhaps there’s some big issue — such as abortion or gun rights or something — where people have diametrically opposed positions, and there are charities which are diametrically opposed. And they’re both thinking of donating to a pair of charities which are opposed with each other. And then maybe they catch up for dinner and notice that this is going to happen. And they say, “Hang on a second. How about if instead of both donating $1,000 to this thing, we instead donate our $2,000 to a charity that, while not as high on our list of priorities for charities, is one that we actually both care about? And then instead of these effects basically cancelling out, we’ll be able to produce good in the world.”

So that’s the general idea of moral trade. And you can see why the moral trade would be a good thing if it’s the case that even though people have different ideas about what’s right, and these ideas can’t all be correct, if they’re generally, more often than not, pointing in a similar direction or something — such that when we better satisfy the overall moral preferences of the people in the world — I think we’ve got some reason to expect the world to be getting better in that process. In which case, moral trade would be a good thing. And it’s an idea that can also lead to that kind of behaviour where you don’t do that last little bit of maximising.

The value of personal character and integrity

Toby Ord: So the reason that effective altruism focuses so much on impact and doing good — for example, through donation — is that we’re aware that there’s this extremely wide variation in different ways of doing good, whether that be perhaps the good that’s done by different careers or how much good is done by donating $1,000 to different charities.

And it’s not as clear that one can get these kinds of improvements in terms of character. So if you imagine an undergraduate, just finishing their degree, about to go off and start a career. If you do get them to give 10 times more than the average person, and to give it 10 times more effectively, they may be able to do 100 times as much good with their giving, and that may be more value than they produce in all other aspects of their life. But if you told them to be a really good character in their life, and that was the only advice, and you didn’t change their career or anything else, it’s not clear that you could get them to produce outcomes like that. And then there’s a question about how much goodness does the virtue create or something, but it doesn’t seem like it comes from the same kind of distribution. It’s unlikely that there’s a version of me out there with some table calculating log-normal distributions of virtue or something like that.

And I think that’s right. But how I think about it is that, ultimately, in terms of the impact we end up having in the world, you could think of virtue as being a multiplier — not by some number between 1 and 10,000 or something with this huge variation, but maybe as a number between -1 and +1 or something like that, or maybe most of the values in that range. Maybe if you’re really, really virtuous, you’re a 3 or something.

But the fact that there is this negative bit is really relevant: it’s very much possible to actually just produce bad outcomes. Clearly, Sam Bankman-Fried seems to be an example of this. And if you’ve scaled up your impact, then you could end up with massive negative effects through having a bad character. Maybe by taking too many risks, maybe by trampling over people on your way to trying to achieve those good outcomes, or various other aspects.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So the point here is that even though virtue in practice doesn’t seem to vary in these enormous ways — in the same way that, say, the cost effectiveness of different health treatments might, or some problems being far more important or neglected than others — all of the other stuff that you do ends up getting multiplied by this number between -1 and 1, which represents the kind of character that you have, and therefore the sort of effects that you have on the project that you’re a part of and the people around you.

And maybe we’ll say a typical level of virtue might be 0.3 or 0.4, but some meaningful fraction of people have a kind of character that’s below zero. Which means that usually, when those people get involved in a project, they’re actually causing harm, even though people might not appreciate it — because they’re just inclined to act like jerks, or they lie too much, or when push comes to shove they’re just going to do something disgraceful that basically sets back their entire enterprise. Or there might be various other mechanisms as well. And then obviously it’s very clear that going from -0.2 to 2 is extremely important, because it determines whether you have a positive or negative impact at all.

Toby Ord: Yeah. And another way to see some of that is when you’re scaling up on the raw impact. For example, suppose you’ve noticed that when founders set up their companies, some of these companies end up making a million dollars for the founders, some make a billion dollars: 1,000 times as much. This is one of these heavy-tailed distributions. And then if you’ve got a person with bad character, the amount of damage they could do with a billion-dollar company is like 1,000 times higher as well as the amount of good they could do with it is 1,000 times higher.

So it’s especially important if someone is going to go and try to just do generically high-impact things that have a positive sign on that overall equation and not a negative one. Another way to look at that is when you have something like earning to give, because there’s an intermediate step where it turns into dollars — and dollars are kind of morally neutral depending on what you do with them, or at least morally ambiguous, as opposed to it directly helping people — then there’s more need to vet those people for having a good character and before joining their project or something like that.

How Toby released some of the highest quality photos of the Earth

Toby Ord: I’d been looking at some beautiful pictures of Saturn by the Cassini spacecraft. Amazing. Just incredible, awe-inspiring photographs. And I thought, this is great. And just as I’d finished my collection of them and we had a slideshow, I thought, I’ve got to go and find a whole lot of the best pictures of the Earth. The equivalent, right? Like fill a folder with amazing pictures of the Earth.

And the pictures I found were nowhere near as good. Often much lower resolution, but also often JPEG-y with compression artefacts or burnt-out highlights where you couldn’t see any details in the bright areas. All kinds of problems. The colours were off. And I thought, this is crazy. And the more I looked into it, I got a bit obsessed in my evenings downloading these pictures of the Earth from space.

I eventually had a pretty good idea of all of the photographs that have been taken of the Earth from space, and it turns out that there aren’t that many spacecraft that have taken good photos. Very few, actually.

If you think about a portrait of a human, the best distance to take a photo of someone is from a couple of metres away. Maybe one metre away would be OK, but any closer than that, they look distorted. And if you go much farther, then you won’t get a good photo; they’ll be too small in the shot. But the equivalent is partway from the Earth to the moon. Low Earth orbit, where the International Space Station is, is too close in: it’s the equivalent to being about a centimetre away from someone’s face. And the moon is a bit too far out, although you can get an OK photograph.

And so it turned out that it was mainly the Apollo programme, where they sent humans with extremely good cameras, with these Hasselblads, up into space, and they trained them in photography. Their photos are just way better than anything else that’s been done, and it’s just this very short period, a small number of years. And I ended up going through all — more than 15,000 — photographs from the Apollo programme and finding the best ones of the Earth from space.

And then I found that there were these archives where people had scanned the negatives, and even then some of the scans were messed up. Some of them were compressed too badly, some of them had blown-out highlights, some of them were out of focus. And for every one of my favourite images, I went and found the very best version that’s been scanned.

And then I found that, surprisingly, using Aperture, a program for fixing up photographs, that I could actually restore them better than had been done before. I was very shocked that all of a sudden my photograph of the blue marble was as good or a little bit better than the one on Wikipedia or the NASA website. And for other photographs that were less well known, I could do much better than had been done before.

And I eventually went through and put in a lot of hours into creating this really nice collection, and made a website for them called Earth Restored, which you can easily find, where you can just go and browse through them all.