A Moral Parliament Tool for Navigating Bioethical Disagreements

By Hayley Clatterbuck @ 2025-10-15T20:28 (+13)

Executive Summary

- Consider these donation allocation dilemmas:

- Should infectious disease funding support providing life-saving medications to those in immediate danger, or air filtration to protect against future illness?

- How should resources be balanced between interventions that respect individual autonomy and those that maximize lives saved but infringe upon autonomy (e.g., mask mandates)?

- Should priority go to helping the worst-off, or to interventions that support the greatest number of people overall?

- Our Moral Parliament Tool allows users to navigate normative, metanormative, and empirical uncertainty. It does so by representing diverse worldviews as delegates in a democratic decision-making process about how to distribute resources to various causes or projects.

- We have added functionality to the original Parliament Tool, which allows it to be adapted to novel resource allocation problems. In this sequence, we demonstrate the versatility and utility of the tool by applying it to various types of problems.

Here, we present a parliament that incorporates delegates with diverse bioethical views. It deliberates about how to allocate resources across three different sets of public health projects.

Introduction

In this sequence, we explore how RP’s Moral Parliament Tool can be adapted to support deliberations on a range of resource allocation problems. In this post, we present a Parliament to model democratic decision-making regarding the allocation of healthcare resources. We consider three sets of hypothetical projects representing three bioethics distribution problems. We demonstrate that the same worldview inputs can be effectively applied to different sets of projects.

We believe that the Moral Parliament is a valuable tool for facilitating democratic deliberation about public health dilemmas. While in-person deliberative groups are increasingly common in bioethics settings, these approaches have several limitations. They can be expensive, time-consuming, fail to provide participants with sufficient background information, and be dominated by certain participants. Digital tools offer promising alternatives to in-person democratic deliberation. In particular, algorithmic methods for democratic deliberation seek to model individuals’ values and preferences, “letting our models of multiple people’s moral values vote over the relevant alternatives” in an automated “deliberative” process (Conitzer, et al. 2017).

You can read more about the motivation for the project, its improvements over existing algorithmic approaches to democratic deliberation, and its results in this paper (currently under review).

Worldviews and projects

We designed the following normative dimensions that worldviews will use to evaluate candidate projects:

- Egalitarianism vs. prioritarianism: distribution of benefits to worst-off versus better-off individuals

- Time of effect: present or future people

- Incremental vs. system change: achieves goals via surgical, incremental changes or systemic changes to social structures

- Age of beneficiaries: children, adults, and the elderly

- Saving vs. improving lives

- Autonomy vs. well-being: people’s abilities to make autonomous choices or effects on general well-being

We modeled six common worldviews in bioethics:

- Social Engineer: Seeks to transform healthcare systems to maximize the overall health of future societies

- Rule of Rescue: Prioritizes helping people who are currently in the most immediate danger

- Capabilities: Focuses on ensuring that every individual has the freedoms and resources required to flourish

- Utilitarian: Aims to maximize the overall amount of well-being and minimize overall suffering

- Libertarian: Prioritizes autonomy and letting individuals make their own healthcare decisions

- Redress past inequalities: Seeks to distribute resources in ways that make up for past healthcare injustices and increase the welfare of disadvantaged groups

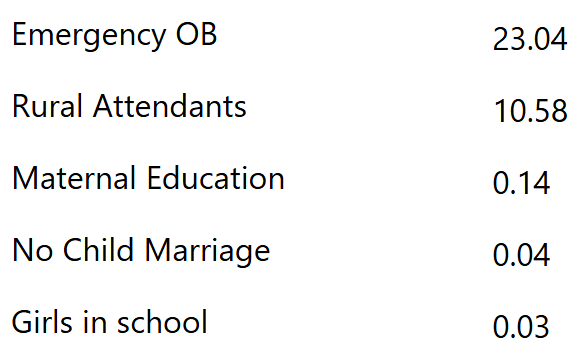

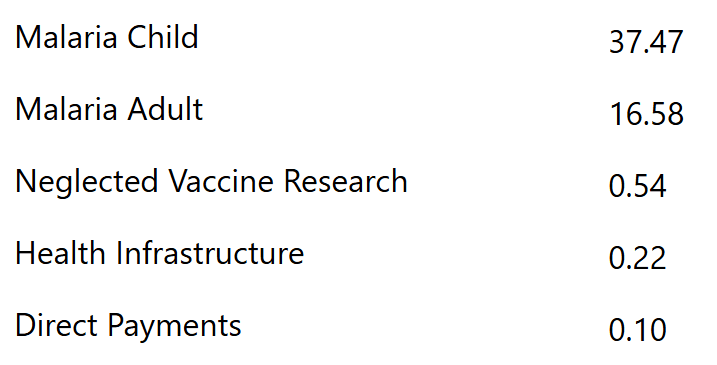

Then, we put representatives of these worldviews into parliamentary decisions about how to allocate resources across the following sets of projects:

- Infectious disease (e.g., mask mandates, vaccination campaigns)

- Maternal healthcare (e.g., increasing enrollment of girls in school, emergency OB facilities)

- Global health (e.g., direct cash payments, child malaria prevention)

Complete project and worldview dimensions can be found here.

Selected results

Project scores by worldview

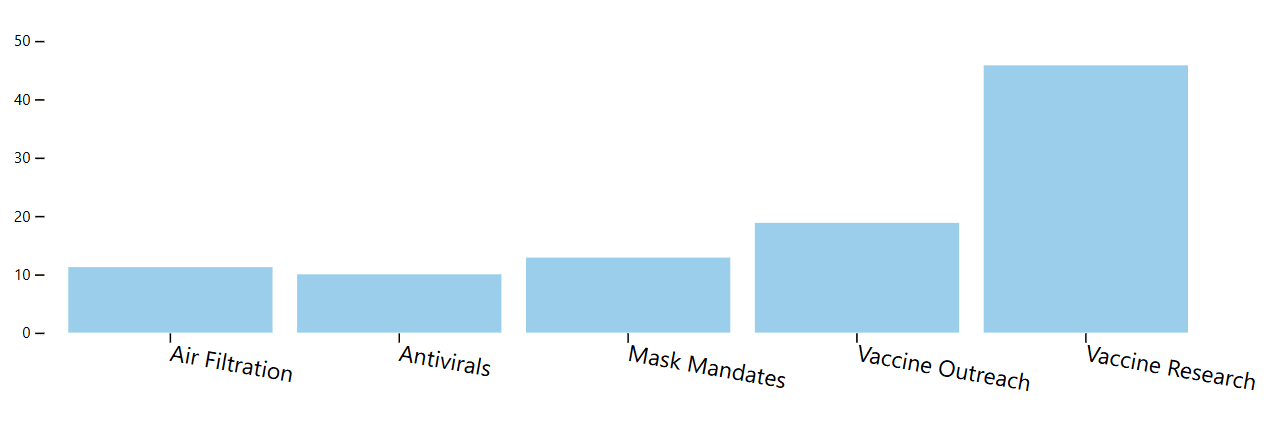

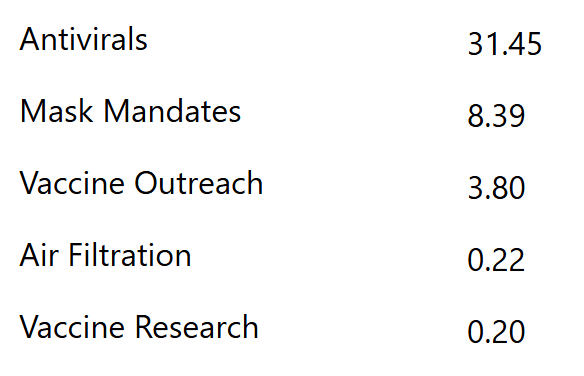

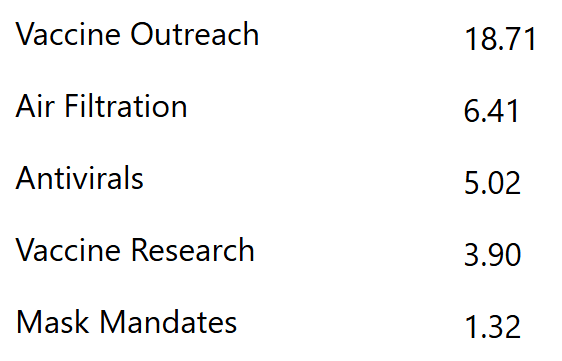

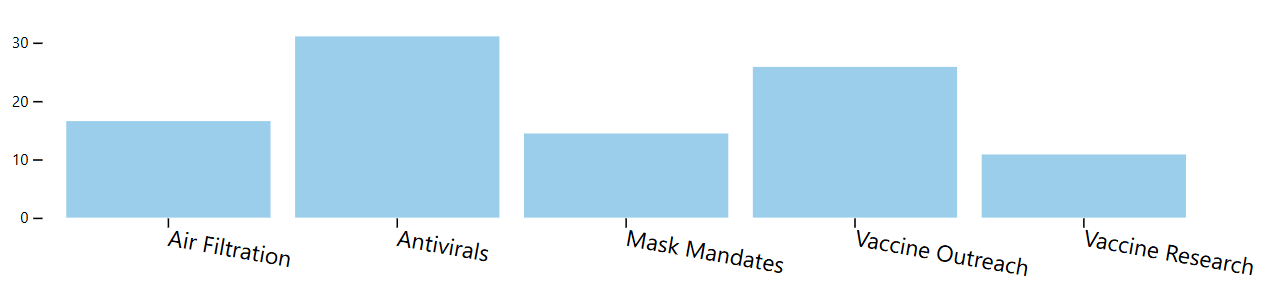

These worldviews often make drastically different evaluations of public health projects. For example, the Rule of Rescue worldview prioritizes helping people who are currently in the most immediate danger. It assigns the following scores:

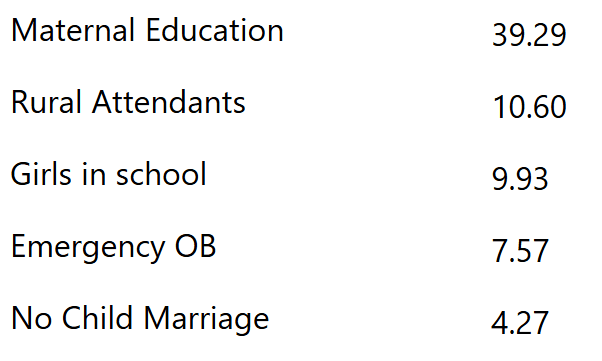

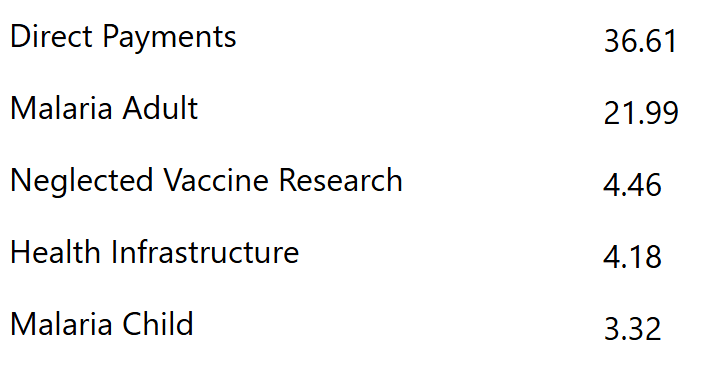

In contrast, the Libertarian worldview prioritizes autonomy and letting individuals make their own healthcare decisions. It assigns the following scores:

By creating a Parliament to deliberate about these resource allocation problems, we demonstrate how the same set of worldview inputs can successfully model deliberations about a diverse range of bioethics dilemmas.

Results of deliberation

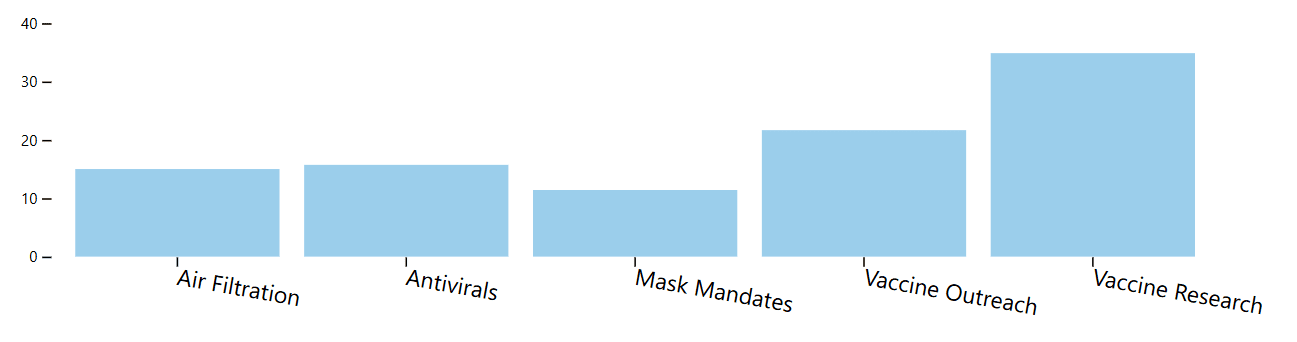

For example, a parliament with equal representation of each worldview (and assuming diminishing returns) deliberates about infectious diseases as follows. Suppose it chooses to Maximize Expected Choiceworthiness (i.e., choosing the allocation that achieves the greatest overall utility, weighted by worldview). In that case, it selects an allocation that gives a slight majority of resources to vaccine projects:

Suppose it decides via Maximin (i.e., choosing the allocation for which the least satisfied worldview gets more utility than any other allocation). In that case, it skews more heavily toward antivirals, which are strongly favored by two of the worldviews.

If the Parliament must vote on a single project to fund, it opts for vaccine outreach, using either Borda or ranked-choice voting.

If we change the composition of the parliament, allocation decisions change predictably (but perhaps less dramatically than expected). For example, if we add more utilitarians and social engineers, allocations are even more skewed toward vaccine projects:

Readers can visit the Bioethics Parliament site to play around with different parliamentary constitutions and project sets.

Conclusion

We intend the examples in this sequence as a proof of concept that the basic framework of the Parliament Tool can be applied to a diverse array of problems. We do not intend them as the final say in modeling these domains. In this case, we constructed hypothetical public health projects. To focus on normative differences, we assumed that all projects had effects of roughly the same magnitude (scale); that is, if you fully valued everything they did, they would all achieve the same amount of value.

If users would like to model more realistic projects, they can adapt the parliament by inputting their own project estimates. We also invite users to create their own worldviews or modify the normative commitments of the worldviews presented here.

If you would like assistance in setting up a custom Parliament application for your organization or to make your own allocation decisions, please contact us.

Acknowledgments

The Moral Parliament Tool is a project of the Worldview Investigation Team at Rethink Priorities. Arvo Muñoz Morán and Derek Shiller developed the tool; Hayley Clatterbuck created the particular parliaments in this sequence. We’d like to thank David Moss and Urszula Zarosa for helpful feedback. If you like our work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can explore our completed public work here.