We should be more uncertain about cause prioritization based on philosophical arguments

By Rethink Priorities, Marcus_A_Davis @ 2025-07-03T12:43 (+178)

Summary

In this article, I argue most of the interesting cross-cause prioritization decisions and conclusions rest on philosophical evidence that isn’t robust enough to justify high degrees of certainty that any given intervention (or class of cause interventions) is “best” above all others. I hold this to be true generally because of the reliance of such cross-cause prioritization judgments on relatively weak philosophical evidence. In particular, the case for high confidence in conclusions on which interventions are all things considered best seems to rely on particular approaches to handling normative uncertainty. The evidence for these approaches is weak and different approaches can produce radically different recommendations, which suggest that cross-cause prioritization intervention rankings or conclusions are fundamentally fragile and that high confidence in any single approach is unwarranted.

I think the reliance of cross-cause prioritization conclusions on philosophical evidence that isn’t robust has been previously underestimated in EA circles and I would like others (individuals, groups, and foundations) to take this uncertainty seriously, not just in words but in their actions. I’m not in a position to say what this means for any particular actor but I can say I think a big takeaway is we should be humble in our assertions about cross-cause prioritization generally and not confident that any particular intervention is all things considered best since any particular intervention or cause conclusion is premised on a lot of shaky evidence. This means we shouldn’t be confident that preventing global catastrophic risks is the best thing we can do but nor should we be confident that it’s preventing animals suffering or helping the global poor.

Key arguments I am advancing:

- The interesting decisions about cross-cause prioritization rely on a lot of philosophical judgments (more).

- Generally speaking, I find the type of evidence for these types of conclusions to be weak (more)

- I think this is true when you consider the direct types of evidence you get on these questions.

- I think it’s also true if you step back and consider what philosophical arguments on these topics look like compared to other epistemic domains.

- Aggregation methods for handling normative uncertainty (i.e., decision procedures) profoundly disagree about what to do at an object level given the same beliefs and empirical facts (more).

- Allocation methods may matter more than normative ethics, particularly if you have low credences across a variety of normative theories.

- Small changes to the set of projects included can radically change the outputs.

- If you were uncertain over normative theories and aggregation methods (which you should be), you likely wouldn’t end up strongly favoring any of GHD, AW, or GCR.

- Small amounts of risk aversion can dramatically change results and tend to favor Global Health and Development (GHD) and animal welfare (public post).

- The evidence for using any given aggregation method to make decisions is weak (more).

- Generally speaking, quantitative studies provide more robust evidence compared to philosophical and empirical foundations of cause prioritization. Moreover, EAs are very skeptical of the strength of evidence available from single RCTs or causal inference via observational studies (more)

- Not only are we skeptical of the specific evidence from those studies, but we are presumptively skeptical of even high-quality studies. It takes additional confirming evidence and the survival of wide scrutiny before accepting conclusions from such evidence.

- The resulting uncertainty about what to do is a serious problem but I’m not convinced some possible responses here eliminate or significantly reduce this problem.

- The nature of what “effective altruism” is or the idea of “doing the most good” doesn’t justify ignoring this uncertainty and leaning into a particular form of consequentialism or utilitarianism (more).

- Nothing about this justifies a largely intuition or “priors” driven approach to determining cause prioritization. If anything, relying heavily on intuitions is worse from an EA perspective than relying on relatively weak philosophical evidence (more).

- Being an anti-realist about ethics may eliminate the concern but may only do so if you basically commit to an “anything goes” version of anti-realism. Also, anti-realism isn’t equally plausible across all relevant domains and the concern about philosophical evidence being weak may undermine staking out such strong anti-realist claims (more).

- You can not escape this by claiming an approach to cross-cause prioritization is “non-philosophical” or is a common sense approach (more).

- This isn’t a reductio ad absurdum against the idea of comparing charities or doing cross-cause comparisons at all. It doesn’t justify an “anything goes” approach in philanthropy and we can still rule that some charities are better than others (more).

- Some might argue they have high confidence in a particular set of normative theories and/or some aggregation methods and this limits this concern. But even if you do (and I don’t think you should) I think both aggregation methods and normative theories are underspecified enough that even with this stipulated, it’s probably unclear what you should practically do (more).

- I’m not in a position to say what this means for any particular actor but I think a big takeaway is we should be humble in our assertions about cross-cause prioritization.

- I’d be keen to see more work on these meta-normative questions of how effective altruists should act in the face of uncertainty about these questions.

- I take these concerns as evidence in favor of diversifying approaches though extensively justifying that take is beyond the scope of this post.

- I think you should remain skeptical that we have really resolved enough of the uncertainties raised here to confidently claim any interventions are truly, all things considered, best.

Cause Prioritization Is Uncertain and Some Key Philosophical Evidence for Particular Conclusions is Structurally Weak

The decision-relevant parts of cross-cause prioritization heavily rely on philosophical conclusions

Where should we give money and resources if we want to take the best moral actions we can? I take this to be perhaps the central question at the heart of the effective altruist (EA) approach to doing good. That there are better and worse ways of improving the world and we can use evidence and reason to investigate where to give in order to select better options is similarly a key pillar in this approach.

I think this claim is important and true but can be overstated in many circumstances if it’s taken to be a claim that we can know with high confidence how many potentially very promising interventions rank relative to each other.

It’s relatively easy to argue, all else equal, that it’s better to save 100 lives rather than 10 or that interventions with robust evidence of effectiveness are more appealing than those without such evidence. It’s harder (but still relatively easy) to argue, when spending charitable dollars it’s better to save 100 lives than spend the same amount of money exposing 100 people to art for one hour each. Not everyone is on board with these claims[1] but they are very difficult to argue against. These are largely taken as background considerations within EA. Importantly, these points aren’t particularly contingent on highly contentious philosophical claims and can be endorsed by people with different views about normative ethics (i.e. deontologists and utilitarians), how to value present vs future people, which decision theory to use, how to compare human to animal welfare, and how to deal with moral uncertainty.

However, some of the main topics of EA concern, such as weighing how causes (like global health and animal welfare) or interventions (say, malaria nets vs corporate campaigns to improve hen welfare) compare to each other, do not turn on uncontroversial questions like whether saving 100 lives is more valuable than saving 10. Rather, I think EA cause prioritization decisions often rest on (implicit or explicit) philosophical considerations that are much tougher to justify reaching with high confidence. This is because the action on, say, deciding between malaria and pandemic prevention often necessarily includes, among other things, consideration of normative views (which ethical theories to use), decision theories (what procedures should we use to select actions), and population ethics (how do we handle problems when actions impact current and future populations). Not only can it be very difficult to compare really disparate outcomes well, but the outcomes of these comparisons are also often heavily theory-laden and fragile to changes in the assumptions or approach used, as WIT pointed out in their recent post on the different types of cause prioritization.

I think this is a general problem for cause prioritization given the reliance on philosophical evidence and particularly a problem for handling decisions under normative uncertainty (how we should combine our ethical views into a single choice if we aren’t certain about a given theory), and selecting among competing methods to aggregate views given uncertainty. This, in turn, is a big problem for reaching high certainty about which specific interventions are best because aggregation methods disagree about what to do and, in my opinion, the evidence for aggregation methods is weak.

Philosophical evidence about the interesting cause prioritization questions is generally weak

Let’s consider an inside view and outside view of how we can think about the strength of evidence for cause prioritization. The inside view being from the perspective of the particulars about the concrete arguments about cause prioritization. The outside view abstracts away these particulars and looks instead at the broader epistemic landscape for similar problems. I think both suggest that we shouldn’t have high confidence in the philosophical arguments needed to justify strong views about the action-relevant points for cross-cause prioritization within EA.

An inside view against having strong views

In philosophy, for the most part when it comes to major considerations like ethical theories (i.e. consequentialism vs deontology) and decisions under normative uncertainty, people aren’t even claiming to demonstrate that X is true, only giving some considerations in favor of X and against Y.

But almost every philosophical argument has a counterargument. I’m not a nihilist about reaching conclusions on any of these matters whatsoever, but on a lot of fundamental conceptual issues of cause prioritization (i.e., normative views, decision theory, aggregation methods, population ethics), the evidence in question is often a series of attributes nearly everyone agrees on but disagrees about how much of a strength and weaknesses each is, or how to add up these considerations.[2]

That is, maybe one issue is “disqualifying” for Susan's consideration but not Tim's. Tim thinks that expected value (EV) reasoning leads to fanaticism (the view there’s always a N high enough that EV recommends an action no matter how small the probability of obtaining the outcome is). Still, Tim thinks this is a cost worth paying to preserve the structure of EV reasoning.[3] By contrast, Susan may think fanaticism is a severe enough issue that we should look for alternatives that avoid that issue.[4] These are the typical terms of the debate when directly considering the specific evidence and arguments presented to adopt one view or another.

A particularly clear example of this dynamic is seen in Chapter 4 of Beckstead’s 2013 thesis On the overwhelming importance of shaping the far future where he considers how different ethical views deal with causing additional people to exist. After considering a variety of population ethics views and thought experiments to test those theories against particular cases, he produced the following table on page 95. The details of what these cases are and the views aren’t particularly relevant to the point I’m making, but “ X” means “The view faces problems with this case” , “ X*” means “The view faces problems with a version of this case”, and “?” means “It isn't clear whether the view has intuitively implausible implications about this case”.

| The Happy Child | The Wretched Child | Obligation to have kids? | Sight or Paid Pregnancy | Repugnant Conclusions | Better to create happy people? | Bad to have kids? | Extinction Cases | The Risk-Averse Mother | The Medical Programmes | Disease Now or Disease Later | Mostly Good or Extinction | |

| Strict Symmetric | ? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Strict Asymmetric | ? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Moderate Symmetric (low weight) | ? | X* | ? | X | X | X | ||||||

| Moderate Asymmetric (low weight) | ? | ? | X* | X* | X | X | X* | |||||

| Unrestricted | ? | X | ? |

Beckstead ultimately took this as evidence in favor of the “unrestricted” view given it fared best in this comparison though he notes (i) this was his judgment of these cases and (ii) one could potentially produce a different set of cases to get a different result (and some of these cases are related).[5] Those are concerns but the bigger concern for me about this is there’s no view here that has no unintuitive implications. Given that, to me, the actionable questions are what series of unintuitive bullets you are willing to bite to endorse any view, how do you weigh those unintuitive demerits against each other, and how do you weigh these demerits against whatever benefits you get from the theory.[6]

This setup isn’t unique to population ethics. I think this dynamic–competing views with varying strengths and weaknesses, backed by competing claims across thought experiments that show different opposing views as unintuitive–also applies to competing decision theories and procedures and normative theories that are central to cross-cause prioritization.[7] People may profess very high confidence that a given view is correct because they perceive their view to be very intuitive (or more intuitive than alternatives) but weighing up which theories survive the intellectual obstacle course of thought experiments doesn’t look like the kind of evidence that can lead one to have high confidence that ultimately we came to the correct conclusion in these domains.

I think this is another way of saying in the domains most relevant to reaching concrete decisions in cross-cause prioritization, the evidence is often insufficient for coming to strong conclusions that a particular view is actually true. It’s really hard for me to believe we could be, say, 90% sure a particular view is right when the evidence looks like this (and I’d often argue you should be far less than 90% confident given this type of evidence).

An outside view on having strong views

But consider a view that abstracts away the particular arguments delivered and consider what this looks like from an outside perspective.[8] Suppose there were ten accounts of some historical biological issue such as the reason for the origin of life. Suppose further that there's been a decades-long disagreement about which theories are correct. The field has disagreements on which methodologies are most appropriate to address the question, disagreements about what each methodology once applied shows, and given the nature of the debate, there is unlikely to ever come strong empirical evidence demonstrating, in fact, one theory is true. Further, as a social matter, suppose scientists who adhere to different theories all get peer-reviewed by the full community, but there’s a strong social and financial incentive to advance the theory you started your career advocating for.

What credence (the measure of your beliefs' strength) should you, someone who’s not a biologist, have in the correct theory? It’s very unlikely to me that the answer would be significantly higher than 0.1, but it definitely wouldn’t be > 0.5.[9] And even if you were a biologist in the field, given the peer disagreement, the weakness of the evidence, and the social incentives, it would seem unjustifiable to place much more credence than 0.2 in theories even if, in practice, a large number of biologists profess credences of ≥ 0.75 in particular theories. Again, perhaps you can make some special case that would justify a higher certainty, but it seems very unlikely you should, on the merits of the epistemic situation, hold 0.75 credence in any theory.

Enough cause prioritization issues take this general shape that you should be really skeptical that you find yourself in the situation of the special biologist that is justified in giving ≥ 0.5 to their favorite theory. For these types of questions the strongest argument given is often a version of saying about an alternative view “That’s unintuitive!” which is not very compelling as an argument for why you should have high confidence in a particular view given people disagree, often strongly, about what’s unintuitive.

But while decades of investigation have been conducted on many of the major philosophical debates there hasn’t been widespread prolonged debate on several issues related to EA. Interspecies comparisons of moral weight, aggregation methods across normative theories, the correct philanthropic discount rate, and many others are largely niche issues.

I submit, philosophy moves slowly and even when it converges on an answer, or a series of answers, it takes robust discussion for that to happen. To a rough approximation, you could say historically, most philosophy has been wrong or at least misguided.[10] In the face of that type of history, I would argue that the best default attitude on any arbitrary philosophical position should be skepticism unless the position is extraordinarily well-mapped out.

It’s always true that “this time could be different,” but to come to strong conclusions on these issues at the heart of cause prioritization seems to me to be like William Godwin and his friends deciding in the early 1800s that they had resolved all the major issues of utilitarianism and now could give detailed object-level advice about how to set up the structure of government to enact the ideal version of utilitarianism.

Aggregation methods disagree

Last year, some of Rethink Priorities' work investigated how different worldviews affect project funding decisions under normative uncertainty. It turned out that the recommended course of action depends significantly on how you combine credences across various worldviews. Different aggregation methods can lead to very different conclusions. This is because the way you weigh preferences and apply decision-making criteria can significantly change the outcome of your analysis.

To endorse one cause area as much more important than everything else you have to adopt a number of philosophical premises[11], many of which are the subject of active philosophical debate and discussion.

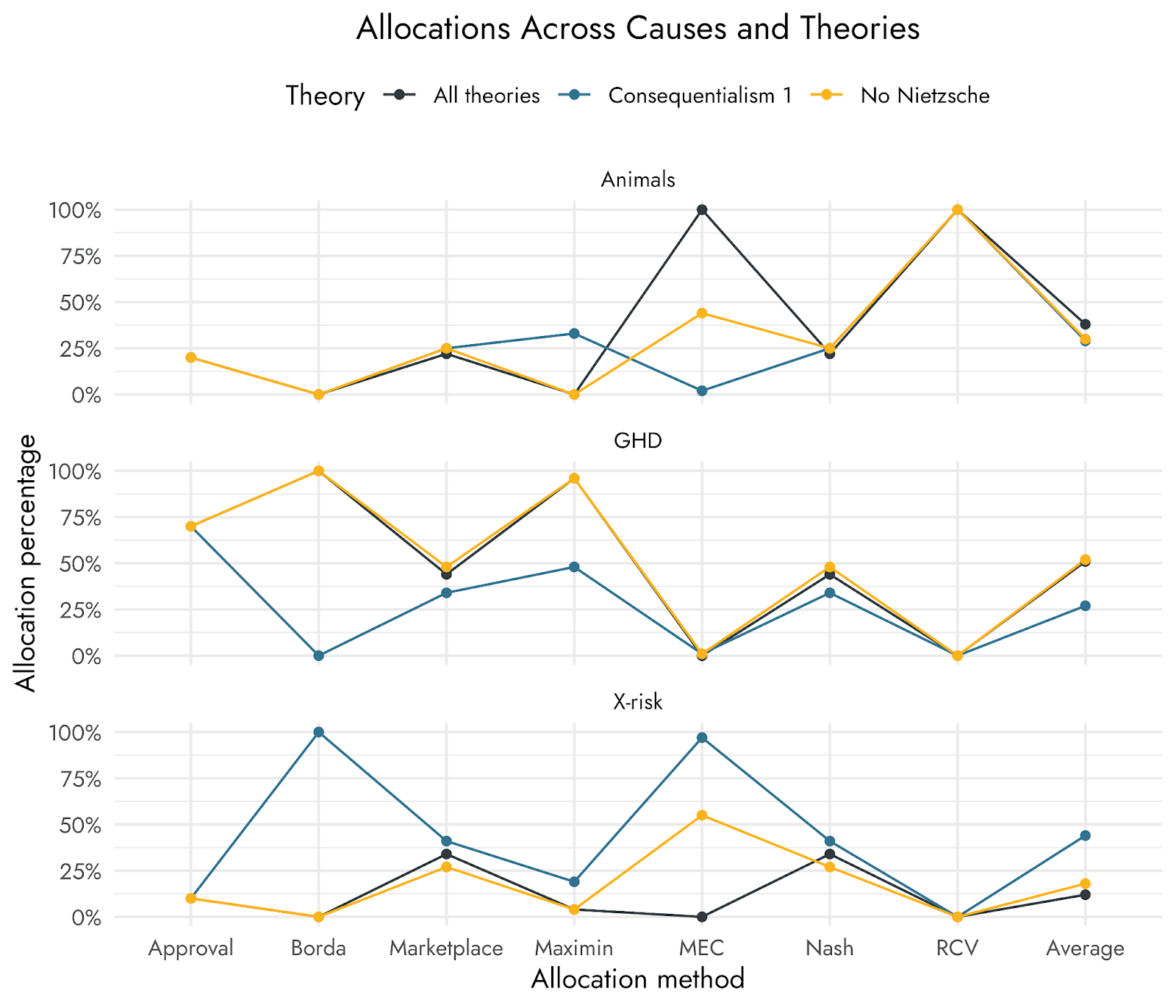

I have used RP’s moral parliament tool to try to see what would happen if you distributed your credences across various ethical theories.[12] You can view the results of that exercise, which show how different aggregation methods would distribute resources across interventions in this spreadsheet and in Figures 1 and 2 below.

Figure 1: Allocations Across Causes and Aggregation Theories. Shows how resources allocated to cause areas varies across aggregation methods. More information on the aggregation methods used and how they are implemented in the underlying tool can be found here. Further details on the inputs used to produce these results can be found in Footnote 12 and all values are in this spreadsheet.

There are a number of takeaways from doing this.

- Aggregation methods may matter more than normative ethics, particularly if you have low credences across various normative theories. Think of "aggregation methods" as different ways of solving a complex puzzle. How you choose to solve the puzzle can significantly change the final picture, even if the puzzle pieces (your fundamental beliefs) stay the same. (See Figure 1).

- Depending on the aggregation method, the same set of normative and empirical commitments can assign ≥ 75%, and in some cases ~100%, of resources to each of Global Health & Development (GHD), Animal Welfare (AW), or Global Catastrophic Risk (GCR) and, in certain cases, different particular projects within areas.

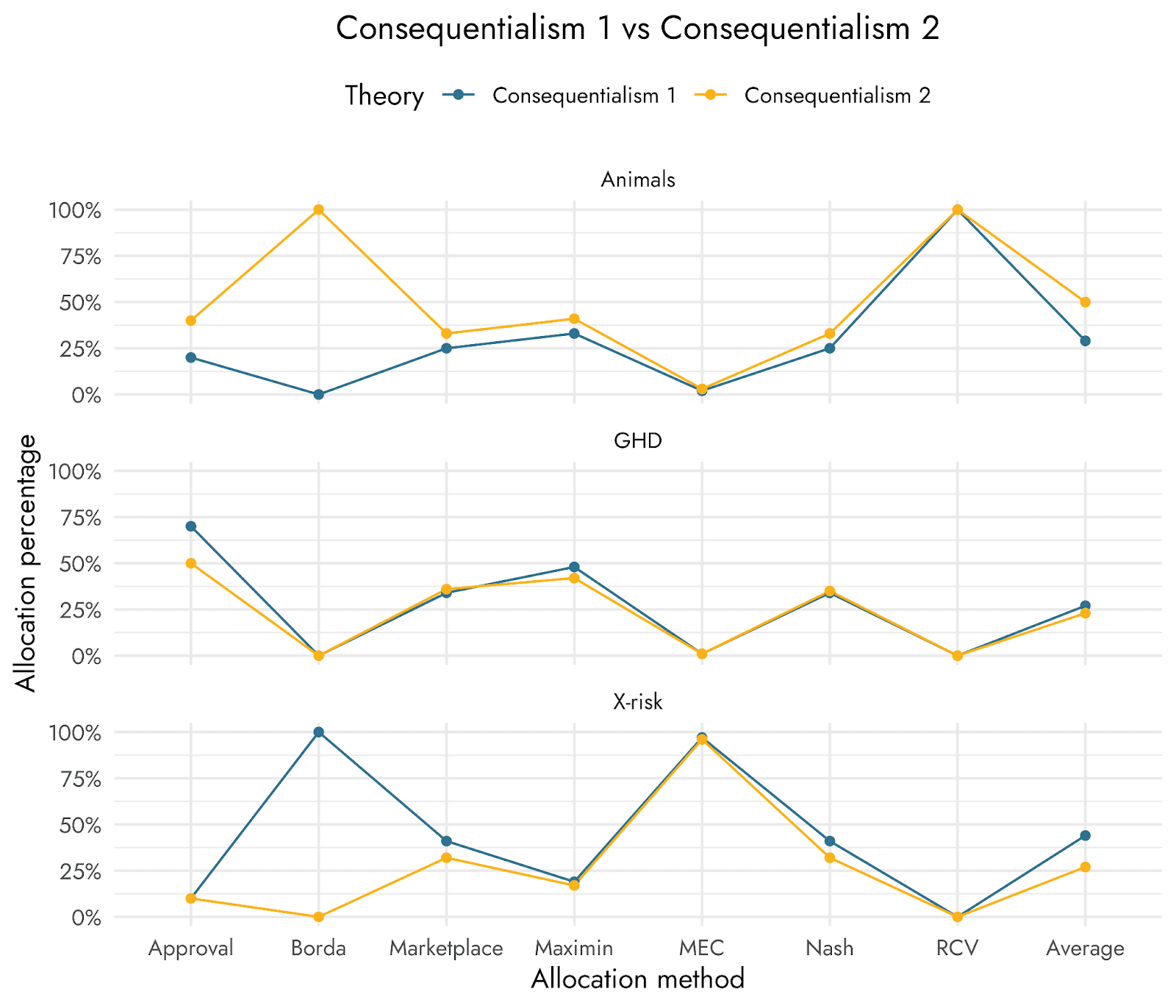

Small changes to the set of projects included can radically change the outputs under some aggregation approaches. Adding a single additional project to be considered can shift the majority of resources away from what was being favored to a different project and/or shift resources more to projects already under consideration. That is, adding a new project isn’t purely additive for the new project with corresponding drops for all other projects. (See Figure 2).[13]

If you were uncertain over normative theories and aggregation methods (which you should be), you likely wouldn’t end up strongly favoring any of GHD, AW, or GCR.[14]

- Small amounts of risk aversion can dramatically change results and tend to favor GHD and animals (you can also see this demonstrated in WIT’s portfolio tool).

Figure 2: Consequentialism 1 vs Consequentialism 2 shows how resources allocated to cause areas varies across aggregation methods when adding an additional project to be considered. Consequentialism 1 contains 3 projects each for each cause area. Consequentialism 2 adds a single project on reducing the worst pest management practices to these nine projects previously considered and produces substantially different results for the Borda method and marginally different results elsewhere. More information on the aggregation methods used and how they are implemented in the underlying tool can be found here. Further details on the inputs used to produce these results can be found in Footnote 12 and all values are in this spreadsheet.

Evidence for aggregation methods is weaker than empirical evidence of which EAs are skeptical

Selecting an aggregation method across normative uncertainty didn’t get a definite treatment until ~2000 with Lockhart’s Moral uncertainty and its consequences, with Will MacAskill’s longer work Normative Uncertainty occurring in 2014. This is barely a blink on the timescale of analytic philosophy. This can be true even though this is already an area of active debate, including MacAskill and Ord 2018 defending maximizing expected choiceworthiness (MEC) as a solution to normative uncertainty and, say, Greaves and Cotton-Barratt 2023 comparing MEC and Nash bargaining.

Even if one finds MacAskill and Ord's arguments for MEC compelling, we must critically examine the strength of philosophical evidence. This work, like most philosophical work, relies on a combination of explicit argument about what follows from what, simplifying modeling assumptions, intuition, and generally has many implicit or explicit choice points.[15] Generally, philosophical arguments, no matter how persuasive, have a historical tendency to be subsequently challenged or dismantled. In fact, I argue that a compelling philosophical argument for MEC's theoretical or practical superiority provides substantially weaker evidence than an empirical social science randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrating a causal effect.[16] And further, I submit the selection effects of caring about optimizing charitable giving so much you end up, say, endorsing GiveWell and reading meta-commentary on cause prioritization, means you are likely very skeptical of the results of such a single RCT.

Within effective altruism circles, there’s a presumptive skepticism of empirical results. The default stance toward empirical research is “interesting initial finding, but let’s see if it holds up to future challenges and replications.” This attitude should similarly guide how we look at the correct answer to EA-related philosophical topics, such as which aggregation method to use to deal with normative uncertainty.

Indeed, for empirical studies, it is common for an initial study claiming a causal relationship to be subsequently complicated or nuanced by follow-up investigations. Holden Karnofsky’s Does X Cause Y? An in-depth evidence review blogpost effectively illustrated this dynamic. The strength of the evidence produced by philosophy in the cross-cause prioritization action-relevant cases is markedly weaker than the types of quantitative evidence that exists in the domain Karnofsky was critiquing and certainly weaker than the RCTs Karnofsky says he likes to rely on.

Objections and Replies

Aren’t we here to do the most good? / Aren’t we here to do consequentialism? / Doesn’t our competitive edge come from being more consequentialist than others in the nonprofit sector?

Consequentialism, and even utilitarianism, underspecifies how to act generally, but uncertainty across the various forms of consequentialism presents these same problems with different aggregation methods suggesting radically different actions. See the consequentialism tabs in the aggregation methods moral parliament results here.

Further, I don’t think the goal of EA is to do whatever consequentialism or utilitarianism says regardless of how confident one should be in the underlying theory or aggregation method.

And while it is true that to a significant extent people in EA are on average much more consequentialist than others working in charity, the point of doing our work is supposed to be improving the world. We’re not a for-profit venture looking for a market-based edge, we’re trying to do what is right and do that well. It’s true we could lean into doing a certain version of utilitarianism and provide some value compared to those that aren’t as clear about how they are reaching their tradeoffs. Still, we should only do this if we think we ought to be advancing this as a normative claim, not because we found an opportunity to sell this vision to ourselves or others.

Can’t I just use my intuitions or my “priors” about the right answers to these questions? I agree philosophical evidence is weak so we should just do what our intuitions say

There are multiple senses of “priors” that are relevant here. To the extent this is about the application of your reflective sense of the credence in all the relevant theories after a review of the evidence for and against them using “priors” may be completely unobjectionable. However, there is another sense that seems relevant which is about taking your unreflective inside-view, or perhaps just subconsciously or consciously inserting your favorite theory as the relevant benchmark, and calling the application of that process using “priors” to reach a determination. In this latter sense using “priors,” which may or may not be synonymous with your intuition, to decide matters of cause prioritization this way is, if anything, worse than just taking strong philosophical stances in light of limited evidence.

To the extent EA has norms, one of them should be clear reasoning and giving evidence for your position. Once you give up doing that, and assert your intuitions for making these calls, you will have often largely abandoned the attempt to reason to the correct answer.

As a point of comparison, it seems quite clear that an individual’s philosophical intuition on many of these matters is even weaker evidence than relying on a single empirical study. Intuitions about these topics should be treated as “break glass in case of emergency” tools, not a key deciding factor. Some reliance may come up, but you should be careful not to overuse them, and when they are used to make important decisions there should be extensive reporting about how and why it was done.

This is not to say we shouldn’t consider intuitions when it’s all we have, or that we can’t, say, combine intuitions about these matters in some rigorous manner. It is to suggest your “priors” in the context should be uncertain and we should be really careful and clear about when we are relying on intuition rather than clear evidence and argument, and be aware of all the biases that could come from doing so.

We can use common sense / or a “non-philosophical” approach and conclude which cause area(s) to support. For example, it’s common sense that humanity going extinct would be really bad; so, we should work on that

This has overlapping issues with the use of “priors” and intuitions discussed above because “common sense” is often a stand-in for the speaker’s views. Additionally, there is very rarely a singular “common sense” answer (and even if you poll people to empirically get such a view, you’d often get different answers across times and locations).

Even putting those issues aside, this approach doesn’t answer the central questions we face. That the lives of the global poor are more important than ruining a suit of someone in a rich country; that it’s bad to torture animals; and that, all else equal, it would be good for humanity to continue to exist are all common sense views (even if contentious once you get into the details). However, this approach doesn’t resolve how to make actual tradeoffs between these common sense claims. The hard cause prioritization questions are about which specific tradeoffs are desirable. Common sense might have an answer to: “Should we try to make humanity continue to exist and have a flourishing future or not?” It doesn’t say anything helpful about: “How many resources should we place on creating that future relative to preventing global poverty now?”

Any answer given to that latter question at least implicitly takes stances on the empirical and philosophical justifications for taking one action rather than another. Similarly, to make decisions in cause prioritization one needs to answer questions like:

- What is the correct amount to weigh different animal species relative to each other and to humans?

- How does one weigh the value of foreigners compared to locals?

- What is the tradeoff between income and health? (How many dollars to the global poor is a year of healthy life worth?)

- How do you value the future beyond the next ~200 years if at all?

- What is the net value of existence now and in the future?

- Can many really weak claims of harm (weak in probability and/or intensity) outweigh one really strong claim of harm? If so, under what circumstances?

It’s implausible that there are “common sense” or “non-philosophical” answers to these questions. Moreover, insofar as there are common sense or “non-philosophical” answers, there is no reason to think that they will lead to a consistent and reasonable overall view.

In any case, part of the appeal of common sense is that it allows us to act with reasonably high confidence. However, it’s hard to think that common sense can provide that here. We will be forced to grapple with difficult, uncomfortable tradeoffs that require explicit reasoning about these tradeoffs.

I’m an anti-realist about philosophical questions so I think that whatever I value is right, by my lights, so why should I care about any uncertainty across theories? Can’t I just endorse whatever views seem best to me?

Being anti-realist in this way that you can set aside the strength of the evidence and arguments for claims in some ways is an untouchable position for this critique of evidence but likely only if you’ve truly committed to ignoring the evidence entirely. Not all anti-realists are completely “anything goes” in this way.

To some extent there is overlap here with the above concern about the use of “priors” on these questions as if you are giving up entirely on using evidence and reason to reach your views, this seems like you would be seems like violating the norm on using evidence and reason to reach your conclusions that EA is built upon. It also seems like the strongest anti-realist stance could justify any arbitrary position including, say, endorsing Derek Parfit’s Future Tuesday Indifference–where a hedonist cares about the quality of their future unless it happens on a future Tuesday–or Parfit’s Within-a-Mile-Altruism, where a person cares only about events that happen within a mile of their home and doesn’t care at all about the suffering of those further than one mile away. This may or may not be too much of a bullet to bite depending on your commitment to anti-realism.

Separately, it may be more plausible to stake out such an anti-realist position on some normative claims than others. An anti-realist position about ethical theories may be more plausible than an anti-realist position about decision theory.

If the evidence in philosophy is as weak as you say, this suggests there are no right answers at all and/or that potentially anything goes in philanthropy. If you can’t confidently rule things out, wouldn’t this imply that you can’t distinguish a scam charity from a highly effective group like Against Malaria Foundation?

No, it doesn’t suggest that anything goes. First, whether there are right answers is one thing; whether we can know those answers is another. Second, whether we can have high confidence is one thing; whether we can get action-relevant evidence is another. To do the hard work of setting priorities in philanthropy, we need action-relevant evidence—which often means acting on significant uncertainties. Still, if the differences between the best charities and the rest are large enough—and they are!—we can make progress.

More concretely, recall that the moral parliament tool I used only included the types of charitable actions that were promising according to the worldviews included. That is, the charity list (which does not consist of real charities) isn’t a definitive list of all interventions that are actually being pursued by all humans. That means there are many charities that are less efficient at saving lives, improving happiness, or creating a just society that would still be strongly disfavored even by the type of approach that relies more modestly on philosophical conclusions in controversial areas. Charities that accomplish the same goals as a different group but less efficiently will be dominated even by this approach.

Additionally, nothing about this approach makes it so, say, you can’t distinguish between a charity that adds value by exposing wealthy individuals to more art will be competitive with corporate campaigns for chickens. Again, there is range restriction here in what is shown since only at least somewhat plausible philosophical views were included.

While I see the concern about this making it less clear what are the best opportunities, I think a more accurate reading of the concern about philosophical evidence being weak is something like “among plausible charitable targets like those included in that moral parliament tool, it’s difficult to draw strong conclusions of one cause area over another” instead of “you typically can’t draw strong conclusions about charity X over charity Y working on the same problem”.

I have high confidence in MEC (or some other aggregation method) and/or some more narrow set of normative theories so cause prioritization is more predictable than you are suggesting despite some uncertainty in what theories I give some credence to

Again, I would note that you likely shouldn’t have strong beliefs given the weak nature of the evidence. But even if you do have strong beliefs it is still likely not super clear what aggregation methods practically suggest to do because:

- Many aggregation methods are underspecified because

- There are numerous potential variations of these methods and small changes in how you approach the problem can significantly alter the recommended actions

- The way you understand and frame normative uncertainty can change how these methods are implemented

- In many cases, the recommended action an aggregation method suggests depends on subtle variations in underlying normative theories. Some methods consider not just the ranking of preferences, but their intensity. This means that how strongly a theory argues for something can be as important as what it argues for.

1. Aggregation methods are underspecified

a. There are a large number of potential variants of these methods

Firstly, MEC is a probability-weighted sum of an action's choiceworthiness relative to all the theories you consider. But to produce that sum, you need some way to handle intertheoretic comparisons. This is an initial choice point as there are many ways you could handle such comparisons and normalize across theories.[17]

Cotton-Barratt, MacAskill, and Ord 2020 suggests mirroring how we handle empirical uncertainty by mapping normative theories onto a single metric while keeping the variance within the theories the same.[18] That does not tell you, among other things, which type of data set with empirical uncertainty we are attempting to model and hence how to handle outliers (extreme values that differ significantly from other data points). As a result, variants on the theme of MEC (or other aggregation methods) might produce very different results.

When handling empirical uncertainty sometimes you should drop outliers (i.e. when such outliers are very likely to be erroneous), other times you may want to amplify outlier weights (i.e. when deviation from middle of a data set is particularly important), and sometimes you might want to maintain but reduce the weight of outliers or regress them back towards the mean (i.e. when what’s important is the shape of the distribution and/or when you suspect outliers are erroneous but directionally correct).

Critical questions arise: Are extreme/outlier values when handling normative uncertainty more like one of these cases than the others? Supposing you think you should amplify outliers, should the outliers be squared or cubed? Supposing you should drop some outliers, when do you start to drop values? Supposing you should do some regressing to the mean at what point do you start the regression?

These considerations could significantly alter what different versions of an aggregation method suggest. There are numerous transformations that could be applied, creating a wide variety of gradations in how a theory processes normative theory outputs.

This issue of nearby variants applies to MEC and many other aggregation methods. For example, when modeling approval voting as a normative aggregation method RP assessed the best possible distribution by the lights of theories under consideration and then had to assign a threshold to determine how close to that optimal distribution an output would have to be to approve of it. There is no natural answer to this question.[19] Similar issues apply to other aggregation methods that rely on bargaining like Nash bargaining (but also to voting methods like score voting and quadratic voting).

b. How you conceptualize the challenge of normative uncertainty can change how you implement aggregation methods

Second, how you conceptualize normative uncertainty may alter how some implementations of aggregation behave. How hard should theories negotiate if they are bargaining? Should theories with large values for certain outcomes refuse to accept any outcome that doesn’t result in them getting their way even if they aren’t in a strong negotiating position with regard to the percentage of seats in a moral parliament? In real parliaments, such tactics might result in a coalition government not being formed or collapsing. However, in real life the range of political actors is broad: it includes parties bargaining hard along with softer negotiators who can almost always reach a compromise; it also includes terrorists who refuse any bargain that is not 100% in their favor on pain of death to others and themselves.

In handling normative uncertainty, are normative theories (or certain specific actions a theory commands) that would demand most or all the resources to themselves because of strong preferences more like terrorists (who are often in real life forbidden from parliament because they refuse to negotiate and/or because they take actions other theories strongly disapprove of) or are they more like coalition partners within a government just driving a hard bargain?

How you analogize this situation could significantly alter which results aggregation methods return (for all but non-weighted voting methods) but how you conceptualize this turns at least in part on what you are trying to accomplish by turning to normative aggregation methods in the first place.[20] I think in light of the weak evidence inherent to resolving disagreements of this kind about the purpose of aggregating across uncertainty, we should be cautious in thinking it’s clear what results various aggregation methods would return even if you give relatively high confidence to certain aggregation methods.

2. Normative theories are underspecified

Finally, as noted by Baker (relevant section in penultimate draft), MEC is potentially susceptible to spending resources on modifications to the normative theories under consideration that amplify the typical results of the theory. That is, for some normative theory A that says what you should do and the stakes are X, there can be an A* theory that says you should do the same thing but the stakes are 1000x. Given the added stakes, if you incorporate A* into your normative considerations they can dominate your actions even if you think A* is 100 times less likely than A. For example, suppose you give contractualism 10% credence. There could be a version of contractualism that takes the same normative approach but applies a 100,000x multiplier to the stakes of all outcomes. If you assigned a 0.1% credence to this modified contractualism it would still dominate standard contractualism if it was incorporated in MEC. In general, so long as we aren’t nearly certain such amplifications are false, such modifications might upend what you think MEC returns as a result from these amplifications could (and possibly would) dominate your actions.

Aggregation methods that rank order theories without consideration of the intensity of preferences within theories will not be affected (like ranked choice voting or approval voting). Still, many, if not all, other aggregation method results could be at least somewhat altered by this consideration. For some, like MEC itself, these amplifications may be the only thing that matters depending on how you handle improbable theories and/or large value outputs from a theory.

In other words, suppose you go all the way in on a normative uncertainty approach like MEC (and you should not). By choosing MEC, you are applying a method that heavily rewards intensity of preferences in theories. And, if you take first order philosophical uncertainty seriously, you may end up heavily endorsing theories considered implausible because you can’t easily rule them out.

Conclusion (or “well, what do I recommend?”)

I have presumptive skepticism against reaching strong conclusions based on limited evidence generally, and that applies as much to philosophical evidence that supports cross-cause prioritization decisions as it does to empirical investigations or scientific studies. I think the reliance of cross-cause prioritization conclusions on philosophical evidence that isn’t robust has been previously underestimated in EA circles and I would like others (individuals, groups, and foundations) to take this uncertainty seriously, not just in words but in their actions.

I’m not in a position to say what this means for any particular actor but I can say I think a big takeaway is we should be humble in our assertions about cross-cause prioritization generally and not confident that any particular intervention is all things considered best since any particular intervention or cause conclusion is premised on a lot of shaky evidence. This means we shouldn’t be confident that preventing global catastrophic risks is the best thing we can do but nor should we be confident that it’s preventing animal suffering or helping the global poor. This applies at the cause level and often at the level of particular interventions when comparing across cause areas. I would be keen to see more work on these meta-normative questions of how effective altruists should act in the face of uncertainty about these questions (i.e. Have we captured all the relevant uncertainties? Are there particular actions that are very robust to these considerations? What are they?).

In short, EA remains much more a set of questions and approach than an answer to me. This despite EA in practice over the last several years becoming much more siloed by cause area.

Overall, I take these concerns as evidence in favor of diversifying because you can’t be sure any given approach is “truly right”, though extensively justifying that take is beyond the scope of this post. Maybe one day our smarter descendants will resolve some of these problems but it’s also possible they won’t because there aren’t answers to them. For now, though, I would say you should remain skeptical that we have really resolved enough of the uncertainties raised here to confidently claim any interventions are truly, all things considered, best. And, I would encourage everyone, no matter what area or intervention they currently think is the best, to reflect explicitly about these uncertainties and how they should update their behavior in light of them.

Acknowledgements

This post was written by Marcus A. Davis. Thank you to Arvo Muñoz Morán, Hayley Clatterbuck, Derek Shiller, Bob Fischer, Laura Duffy, David Moss, and Ula Zarosa for their helpful feedback. Thanks to Willem Sleegers and Arvo Muñoz Morán for providing graphs showing the results of the use of the moral parliament tool. Rethink Priorities is a global priority think-and-do tank aiming to do good at scale. We research and implement pressing opportunities to make the world better. We act upon these opportunities by developing and implementing strategies, projects, and solutions to key issues. We do this work in close partnership with foundations and impact-focused non-profits or other entities. If you're interested in Rethink Priorities' work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can explore our completed public work here. You can also subscribe to my Substack Charity for All here, which will have a short version of this post next week.

- ^

Indeed, if everyone was on board with this approach, “the EA approach” wouldn’t really be considered a distinct thing. If you’re interested in a polemic explanation for why you should take this approach at all see this piece by Dylan Matthews on why saving the lives of kids should take precedence over art.

- ^

One might retort: “Isn’t this a philosophical argument you are using to reach this conclusion? If we should be so skeptical of philosophical arguments, I should not believe this argument. But if the evidence was generally as weak as you say then aren’t you in fact endorsing a kind of anything goes approach?” I address the latter claim at greater length below. On the former I would note that I’m not making an argument against using any and all philosophical arguments under any circumstances. The main concern is about relying on what seem like compelling arguments to reach high confidence positions. I think this concern is most acute in domains where relatively few people have engaged, relatively little time has gone by (making prolonged reflection difficult), and the nature of the discussion makes definitive evidence very difficult to find.

- ^

One way of dealing to preserve the general structure of EV may be to round down sufficiently small probabilities, though that introduces additional complications as discussed in RP’s 2023 note Fanaticism, Risk Aversion, and Decision Theory.

- ^

Tim and Susan might also disagree on what the implications of fanaticism are. The more you think fanaticism leads to conclusions that are absurd (like time travel or multiverse branching see Shiller 2022), the more you may be inclined to adopt alternative approaches to EV.

- ^

To be clear, I think Beckstead deserves a lot of credit for putting all of these into a table to weigh up the pros and cons. This is really unusual in philosophy. I picked this example because Beckstead made explicit what is often implicit in philosophy in these domains.

- ^

In a way, much of Parfit’s treatise Reasons and Persons (parts three, four, and five) is an extended version of this box checking for which personal identity and population ethics views have unintuitive implications, including the famous “Repugnant Conclusion” (Chapter 17, page 388) which suggests the kind of “unrestricted” population view Beckstead above endorses ultimately endorses this claim: “For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.” Parfit thinks it’s intuitive that there are some things in life that are really valuable and can’t be outweighed by any amount of “Muzak and potatoes” distributed across a really large population. Personally, I've never found the sound of Muzak or the taste of potatoes that bad.

- ^

For example, in decision theory there are debates about how seriously to consider being “Dutch Booked” which can happen if your beliefs aren’t consistent in a particular way, if someone were to make a series of bets against your stated or implied beliefs you would consistently lose money. See Vineberg 2022, the SEP article on Dutch Book arguments. Or, more generally, there is consideration of which axioms are requirements of rationality, and which results of different theories are so unintuitive as to compel alternative theories. Wilkinson 2020, In defense of fanaticism, defends fanaticism primarily by arguing alternative theories have irredeemable faults. In general, these debates are often, at core, debates over which conclusions are counterintuitive and whether implications of a theory can be so counterintuitive as to compel selecting alternative theories.

- ^

This section generally follows Fischer 2024 - Unpublished manuscript.

- ^

A central question to determine how confident you should be would be how accurately you have mapped the set of viable theories. If you expect there to be twenty or thirty new theories in the following century, it could be that even 0.1 in the current “best” theory is extremely overconfident. H/t to Arvo Muñoz Morán and Derek Shiller for this point.

- ^

Another way of reading philosophical history–particularly the topics relevant to this conversation in epistemology and metaethics–would be to say many of the problems are actually largely unsolvable dilemmas. Were one to take this reading instead of the one I suggest it would still imply that we shouldn’t be very confident we have reached the right answers. H/t to Ula Zarosa for this point.

- ^

Of course, this is barring some extreme empirical beliefs. See footnote 14 for more on how this plays out.

- ^

I assigned equal credence to all theories used in our moral parliament project (All theories), all but Nietzscheanism (No Nietzsche), and only the consequentialist theories (Consequentialism). I assigned three projects each from AW, GHD, and GCR for each of these tabs labeled “1” and for those labeled “2” I used all the same inputs except I included an additional project on reducing the worst pest management practices. The “Popular theories” tabs apply an uneven allocation of credence across normative theories with the same difference in projects across tabs “1” and “2”. From rounding in the underlying model values may not add up to precisely 100%.

- ^

I chose to add a project just to see what happened to the distribution across aggregation methods not because of this expected impact. Figure 2 shows how different combinations of projects perform under Consequentialism because it is an area very relevant to many EAs, not because I found the area that most highlights this change. I suspect there are bigger possible changes from changes in project selection via exploration with this tool for various aggregation methods depending on credences placed in various theories.

- ^

Naturally, with sufficiently strong empirical views that, say, global health interventions don’t work or we can have very high confidence in the effects of particular x-risk interventions you might still reach such a conclusion even if you were uncertain across normative views. If, for example, you assume all life on earth will certainly, no matter your actions, go extinct next year then the value of the long term future and thus GCR risk prevention will be quite different than if you don’t assume that. Some such empirical views could be justified but as a general rule I would tend to argue, separately, you probably shouldn’t have such views though the reasons for that are too far afield from this post to address here.

- ^

For a further discussion of some of these choice points, see the consideration of MEC in the section below on aggregation methods and normative theories being underspecified. To be clear, having choice points isn’t a weakness of this argument relative to other philosophical arguments of this kind. The issue I have is systematic about this class of arguments.

- ^

This is underspecified, but we can clarify by saying a social science RCT powered to detect 1 SD of an effect size on the key parameter is directionally correct. Informally, over the past year I have taken to asking EAs the admittedly underspecified question of something like “how confident are you that a published RCT powered to detect a 1 SD effect and which finds a 1 SD effect is directionally correct?” and the answers range from 10-70%. But I take this as very weak (effectively zero) evidence towards knowing what would happen with a systematic approach.

- ^

As an initial example, I use “choiceworthiness” the way the authors would but should note this isn’t a highly common term. There are other ways you could imagine a decision could have high “choiceworthiness.” For example, a decision could be considered “choiceworthy” because of how it weighs the importance of the outcome, the extent it balances tradeoffs, the extent to which it minimizes blameworthiness or regretability. If you interpreted “choiceworthiness” in these different ways, it seems plausible it could lead to significantly different conclusions about what should be done. H/t to Derek Shiller for this point.

- ^

I should preemptively note that, on the whole, I like MEC and I’m glad the idea was put forward. The criticisms I make of it below aren’t intended to be taken as definitive takes against it (that would go against the ethos of this post) that represent my all things considered position, or even an argument that some other theory is my plurality favorite. Many of the potential issues I raise apply to other solutions to normative uncertainty and I largely discuss MEC because of the prominence in EA circles. Were I talking to a different audience, I would use different examples.

- ^

For example, different democracies, and different actions within the same democracy, often require different thresholds for certain actions to take place. In parliamentary systems there are electoral thresholds which specify a minimum percentage of votes (in a district and/or nationally) before a party can obtain seats in a legislature at all. The precise percentage is not standard across democracies but if a party falls below, say, 5% they may not have a representative at all for any votes. Once the representatives have been selected, sometimes a policy requires a majority plus one threshold (this is typical), but other times there are supermajority requirements (and/or district or state requirements) such as when the state or national constitution is being modified. What that supermajority threshold is varies across democracies (and sometimes depending on the precise policy being enacted or repealed). It is, at best, murky whether there’s a method which allows us to port such rules cleanly into normative aggregation method consideration, and to determine what the requirements are for assent (or dissent) within and across normative theories in this context.

- ^

This is speculative but as an example consider T.M. Scanlon, perhaps the world’s most famous contractualist, endorses a view that restricts moral acts if that decision could be “reasonably rejected by at least one person” as Derek Parfit put it on pg 360 of On What Matters Volume One. Would Scanlon sign on to MEC as the correct way to deal with normative uncertainty? MEC aggregates value across individuals (if a theory does so), and gives preference to the value a theory says an action has relative to the typical action taken by that theory (operating based on variance). I think this type of solution would be a pretty big departure for Scanlon given he refused a potentially more modest attempt by Parfit to integrate his contractualism with consequentialism and deontology in Parfit’s On What Matters Volume Two. The Scanlonian solution to normative uncertainty, if there is one, is potentially minmaxing, since it gives strongest weight to the least satisfied theories. I don’t think Scanlon would condone someone getting outvoted of their resources if their claim against an act was strong (so potentially every voting method is out?), and he very likely wouldn't endorse a meta-solution that says many small claims of potential future people could outweigh the existing very large harms to living people. Going to meta-normative uncertainty doesn't escape that the problem Scanlon, and people like him, are attempting to solve for may be fundamentally different from approaches like MEC which are roughly EV-maximizing across theories.

Lukas_Gloor @ 2025-07-04T14:36 (+10)

I think the discussion under "An outside view on having strong views" would benefit from discussing how much normative ethics is analogous to science and how much it is anologous to something more like personal career choice (which weaves together personal interests but still has objective components where research can be done -- see also my post on life goals).

FWIW, I broadly agree with your response to the objection/question, "I’m an anti-realist about philosophical questions so I think that whatever I value is right, by my lights, so why should I care about any uncertainty across theories? Can’t I just endorse whatever views seem best to me?"

As forum readers probably know by now, I think anti-realism is obviously true, but I don't mean the "anything goes" type of anti-realism, so I'm not unsympathetic to your overall takeaway.

Still, even though I agree with your response to the "anything goes" type of anti-realism, I think you'd ideally want to engage more with metaethical uncertainty and how moral reflection works if (the more structure-containing) moral anti-realism is true.

I've argued previously that moral uncertainty and moral realism are in tension.

The main argument in that linked post goes as follows: Moral realism implies the existence of a speaker-independent moral reality. Being morally uncertain means having a vague or unclear understanding of that reality. So there’s a hidden tension: Without clearly apprehending the alleged moral reality, how can we be confident it exists?

In the post, I then discuss three possible responses for resolving that challenge and explain why I think those responses all fail.

What this means is that moral uncertainty almost by necessity (there's a trivial exception where your confidence in moral realism is based on updating to someone's else's expertise but they have not yet told you the true object-level morality that they believe in) implies either metaethical uncertainty (uncertainty between moral realism and moral anti-realism) or confident moral anti-realism.

That post has been on the EA forum for 3 years and I've not gotten any pushback on it yet, but I've also not seen people start discussing moral uncertainty in a way that I don't feel like sounds subtly off or question-begging in light of what I pointed out. Instead, I think one should ideally discuss how to reason under metaethical uncertainty or how to do moral reflection within confident moral anti-realism.

If anyone is interested, I spelled out how I think we would do that here:

The “Moral Uncertainty” Rabbit Hole, Fully Excavated

It's probably one of the two pieces of output I'm most proud of. My earlier posts in the anti-realism sequence covered ideas that I thought many people already understood, but this one let me contribute some new insights. (Joe Carlsmith has written similar stuff and writes and explains things better than I do— I mention some of his work in the post.)

If someone just wants to read the takeaways and not the underlying arguments for why I think those takeways apply, here they are:

Selected takeaways: good vs. bad reasons for deferring to (more) moral reflection

To list a few takeaways from this post, I made a list of good and bad reasons for deferring (more) to moral reflection. (Note, again, that deferring to moral reflection comes on a spectrum.)

In this context, it’s important to note that deferring to moral reflection would be wise if moral realism is true or if idealized values are “here for us to discover.” In this sequence, I argued that neither of those is true – but some (many?) readers may disagree.

Assuming that I’m right about the flavor of moral anti-realism I’ve advocated for in this sequence, below are my “good and bad reasons for deferring to moral reflection.”

(Note that this is not an exhaustive list, and it’s pretty subjective. Moral reflection feels more like an art than a science.)

Bad reasons for deferring strongly to moral reflection:

- You haven’t contemplated the possibility that the feeling of “everything feels a bit arbitrary; I hope I’m not somehow doing moral reasoning the wrong way” may never go away unless you get into a habit of forming your own views. Therefore, you never practiced the steps that could lead to you forming convictions. Because you haven’t practiced those steps, you assume you’re far from understanding the option space well enough, which only reinforces your belief that it’s too early for you to form convictions.

- You observe that other people’s fundamental intuitions about morality differ from yours. You consider that an argument for trusting your reasoning and your intuitions less than you otherwise would. As a result, you lack enough trust in your reasoning to form convictions early.

- You have an unreflected belief that things don’t matter if moral anti-realism is true. You want to defer strongly to moral reflection because there’s a possibility that moral realism is true. However, you haven’t thought about the argument that naturalist moral realism and moral anti-realism use the same currency, i.e., that the moral views you’d adopt if moral anti-realism were true might matter just as much to you.

Good reasons for deferring strongly to moral reflection:

- You don’t endorse any of the bad reasons, and you still feel drawn to deferring to moral reflection. For instance, you feel genuinely unsure how to reason about moral views or what to think about a specific debate (despite having tried to form opinions).

- You think your present way of visualizing the moral option space is unlikely to be a sound basis for forming convictions. You suspect that it is likely to be highly incomplete or even misguided compared to how you’d frame your options after learning more science and philosophy inside an ideal reflection environment.

Bad reasons for forming some convictions early:

- You think moral anti-realism means there’s no for-you-relevant sense in which you can be wrong about your values.

- You think of yourself as a rational agent, and you believe rational agents must have well-specified “utility functions.” Hence, ending up with under-defined values (which is a possible side-effect of deferring strongly to moral reflection) seems irrational/unacceptable to you.

Good reasons for forming some convictions early:

- You can’t help it, and you think you have a solid grasp of the moral option space (e.g., you’re likely to pass Ideological Turing tests of some prominent reasoners who conceptualize it differently).

- You distrust your ability to guard yourself against unwanted opinion drift inside moral reflection procedures, and the views you already hold feel too important to expose to that risk.

Marcus_A_Davis @ 2025-07-09T18:42 (+6)

Hey Lukas,

Thanks for the detailed reply. You raise a number of different interesting points and I’m not going to touch on all of them, given a lack of time but there are a few I want to highlight.

the discussion under "An outside view on having strong views" would benefit from discussing how much normative ethics is analogous to science and how much it is anologous to something more like personal career choice (which weaves together personal interests but still has objective components where research can be done -- see also my post on life goals).

While I can see how you might make this claim, I don’t really think ethics is very analogous to personal career choice. Analogies are always limited (more on this later) but I think this analogy probably implies too much “personal fit” in career choice which are often a lot about “well, what do you like to do?” so much as they are “this is what will happen if you do that?”. I think you’re largely making the case more for the former, with some part of the latter and for morality I might push for a different combination, even assuming a version of anti-realism. But perhaps all this breaks down on what you think of career choice, where I don’t have particularly strong takes.

I think anti-realism is obviously true, but I don't mean the "anything goes" type of anti-realism, so I'm not unsympathetic to your overall takeaway.

Still, even though I agree with your response to the "anything goes" type of anti-realism, I think you'd ideally want to engage more with metaethical uncertainty and how moral reflection works if (the more structure-containing) moral anti-realism is true.

You’re right I haven’t engaged here about what normative uncertainty means in that circumstance but I think, practically, it may look a lot like the type of bargaining and aggregation referenced in this post (and outlined elsewhere), just with a different reason for why people are engaged in that behavior. In one case, it’s largely because that’s how we’d come to the right answer but in other cases it would be because there’s no right answer to the matter and the only way to resolve disputes is through aggregating opinions across different people and belief systems.

That said, I believe–correct me if I’m wrong–your posts are arguing for a particularly narrow version of realism that is more constrained than typical and that there’s a tension between moral realism and moral uncertainty.

Stepping back a bit, I think a big thrust of my post is that you generally shouldn’t make statements like “anti-realism is obviously true” because the nature of evidence for that claim is pretty weak, even if the nature of the arguments for you reaching that conclusion were clear and are internally compelling to you. You’ve defined moral realism narrowly so perhaps this is neither here nor there but, as you may be aware, most English-speaking philosophers accept/lean towards moral realism despite you noting in this comment that many EAs who have been influential have been anti-realists (broadly defined). This isn’t compelling evidence, but it is evidence against the claim that anti-realism is "obviously correct” since you are at least implicitly claiming most philosophers are wrong about this issue.

What this means is that moral uncertainty almost by necessity (there's a trivial exception where your confidence in moral realism is based on updating to someone's else's expertise but they have not yet told you the true object-level morality that they believe in) implies either metaethical uncertainty (uncertainty between moral realism and moral anti-realism) or confident moral anti-realism.

I’ve read your post on moral uncertainty and moral realism being in tension (and the first post where you defined moral realism) and I’m not sold on the responses you provide to your challenge. Take this section:

Still, I think the notion of “forever inaccessible moral facts” is incomprehensible, not just pointless. Perhaps(?) we can meaningfully talk about “unreachable facts of unknown nature,” but it seems strange to speak of unreachable facts of some known nature (such as “moral” nature). By claiming that a fact is of some known nature, aren’t we (implicitly) saying that we know of a way to tell why that fact belongs to the category? If so, this means that the fact is knowable, at least in theory, since it belongs to a category of facts whose truth-making properties we understand. If some fact were truly “forever unknowable,” it seems like it would have to be a fact of a nature we don’t understand. Whatever those forever unknowable facts may be, they couldn’t have anything to do with concepts we already understand, such as our “moral concepts” of the form (e.g.,) “Torturing innocent children is wrong.”

I could retort here that it seems totally reasonable to argue that there’s a fact of the matter about what caused the Big Bang or how life on Earth began. What caused these could conceivably be totally inaccessible to us now but still related to known facts. Nothing about not knowing how these things started commits us to say–what I take to be the equivalent in this context–that the true nature of those situations has nothing to do with concepts we understand like biology or physics. Further, given what we know now in these domains, I think it’s fair to rule out a wide range of potential causes of them and constrain things to a reasonable set of targets that it may have caused them.

The analogy here seems reasonable enough with morality to me that you shouldn’t rule this type of response out.

Similarly, you say the following to branch two of possible responses to your claim:

To summarize, the issue with self-evident moral statements like “Torturing innocent children is wrong” is that they don’t provide any evidence for a moral reality that covers disagreements in population ethics or accounts of well-being. To be confident moral realists, we’d need other ways of attaining moral knowledge and ascertaining the parts of the moral reality beyond self-evident statements. In other words, we can’t be confident moral realists about a far-reaching, non-trivial, not-immediately-self-evident moral reality unless we already have a clear sense of what it looks like.

I don’t fully buy this argument for similar reasons to the above. This seems more like an argument that to be confident moral realists who assert correct answers to most/all the important questions we need strong evidence of moral realism in most/all domains than it is an argument that we can’t be moral realists at all. One way I might take this (not saying you’d agree) would be to say you think moral realism that isn’t action guiding on the contentious points isn’t moral realism worth the name because all the value of the name is in the contentious points (and this may be particularly true in EA). But if that phrasing of the problem is acceptable, then we may be basically only arguing about the definition of “moral realism” and not anything practically relevant. Or, one could say we can’t be confident moral realists given the uncertainty about what morality entails in a great many cases and I might retort “we don’t need to be confident in order to choose among the plausible options so long as we can whittle things down to restricted set of choices and everything isn’t up for grabs.” This would be for basically the same reasons a huge number of potential options aren’t relevant for settling on the correct theory of abiogenesis or taking the right scientific actions given the set of plausible theories.

But perhaps a broader issue is I, unlike many other effective altruists, am actually cool with (in your words) “minimalist moral realism” being fine and using aggregation methods like those mentioned above to come to final takes about what to do given the uncertainty. This is quite different from confidently stating “the correct answer is this precise version of utilitarianism, and here’s what it says we need to do…”. I don’t think what I’m comfortable saying obviously qualifies as an insignificant moral realism relative to such a utilitarian even if the reasons for reaching the suggested actions differed.

But stepping back, this back and forth looks like another example of the move I criticized above because you are making some analogies and arguing some conclusion follows from those analogies, I’m denying those analogies, and therefore denying the conclusion, and making different analogies. Neither of us has the kind of definitive evidence on their side that prevails in science domains here.

So, how confident am I that you’re wrong? Not super confident. If the version of moral anti-realism you say is true and it results in something like your life-goals framework as the best way to decide ethical matters, then so be it. But the question is what to do given uncertainty that this is the correct approach, and that assuming it’s the correct approach we know what it recommends differs from how we’d otherwise behave. I don’t think it’s clear to me meta-ethical uncertainty about realism or anti-realism is a highly relevant factor in deciding what to do unless, again, someone is embracing a “anything goes” kind of anti-realism which neither of us are endorsing.

Lukas_Gloor @ 2025-07-12T13:34 (+4)

Thanks for engaging with my comment (and my writing more generally)!

You’re right I haven’t engaged here about what normative uncertainty means in that circumstance but I think, practically, it may look a lot like the type of bargaining and aggregation referenced in this post (and outlined elsewhere), just with a different reason for why people are engaged in that behavior.

I agree that the bargaining you reference works well for resolving value uncertainty (or resolving value disagreements via compromise) even if anti-realism is true. Still, I want to flag that for individuals reflecting on their values, there are people who, due to factors like the nature and strength of their moral intuitions and their history of forming convictions related to their EA work, (etc.,) will want to do things differently and have fewer areas than your post would suggest where they remain fundamentally uncertain. Reading your post, there’s an implication that a person would be doing something imprudent if they didn’t consider themselves uncertain on contested EA issues, such as whether creating happy people is morally important. I’m trying to push back on that: Depending on the specifics, I think forming convictions on such matters can be fine/prudent.

Stepping back a bit, I think a big thrust of my post is that you generally shouldn’t make statements like “anti-realism is obviously true” because the nature of evidence for that claim is pretty weak, even if the nature of the arguments for you reaching that conclusion were clear and are internally compelling to you.

I’m with you regarding the part about evidence being comparatively weak/brittle. Elsewhere, you wrote:

But stepping back, this back and forth looks like another example of the move I criticized above because you are making some analogies and arguing some conclusion follows from those analogies, I’m denying those analogies, and therefore denying the conclusion, and making different analogies. Neither of us has the kind of definitive evidence on their side that prevails in science domains here.

Yeah, this does characterize philosophical discussions. At the same time, I'd say that's partly the point behind anti-realism, so I don't think we all have to stay uncertain on realism vs. anti-realism. I see anti-realism as the claim that we cannot do better than argument via analogies (or, as I would say, "Does this/that way of carving out the option space appeal to us/strike us as complete?"). For comparison, moral realism would then be the claim that there's more to it, that the domain is closer/more analogous to the natural sciences. (No need to click the link for the context of continuing this discussion, but I elaborate on these points in my post on why realists and anti-realists disagree. In short, I discuss that famous duck-rabbit illusion picture as an example/analogy of how we can contextualize philosophical disagreements under anti-realism: Both the duck and the rabbit are part of the structure on the page and it’s up to us to decide which interpretation we want to discuss/focus on, which one we find appealing in various ways, which one we may choose to orient our lives around, etc.)

You’ve defined moral realism narrowly so perhaps this is neither here nor there but, as you may be aware, most English-speaking philosophers accept/lean towards moral realism despite you noting in this comment that many EAs who have been influential have been anti-realists (broadly defined). This isn’t compelling evidence, but it is evidence against the claim that anti-realism is "obviously correct” since you are at least implicitly claiming most philosophers are wrong about this issue.

(On the topic of definitions, I don't think that the disagreements would go away if the surveys had used my preferred definitions, so I agree that expert disagreement constitutes something I should address. (Definitions not matching between philosophers isn’t just an issue with how I defined moral realism, BTW. I'd say that many philosophers' definitions draw the line in different places, so it's not like I did anything unusual.))