[Aceso Under Glass] FTX, Golden Geese, and The Widow’s Mite

By Raemon @ 2025-09-30T18:30 (+30)

This is a linkpost to https://acesounderglass.com/2025/09/17/ftx-golden-geese-and-the-widows-mite/

(This post is by Elizabeth Van Nostrand)

From 2019 to 2022, the cryptocurrency exchange FTX stole 8-10 billion dollars from customers. In summer 2022, FTX’s charitable arm gave me two grants totaling $33,000. By the time the theft was revealed in November 2022, I’d spent all but 20% of it.

The remaining money isn’t mine, and I don’t want it. I would like to give this money to the FTX estate, but they are not returning my calls. If this post fails to get their attention in the next month, I will donate the money to Feeding America. In the meantime, I’d like to talk about why I made this decision, and why I think other people should do likewise.

Background

FTX was a crypto-and-derivatives exchange that billed itself as “the above board, by the book legitimate, exchange.” Several of its executives were members of Effective Altruism, a movement based on ruthlessly prioritizing donations to do the greatest good for the greatest number. EA’s presence in FTX was strong enough that FTX booked an ad campaign around CEO Sam Bankman-Fried’s intent to spend his wealth on good causes.

He is now serving a 25 year prison sentence for fraud.

Starting in 2021, FTX began to firehose money. $93m to political causes (some of which was probably buying favorable regulation) and $190m to explicitly philanthropic ones. The donations include domains like AI safety (e.g. $5m for Ought, which aims to make humans wiser using AI), biosecurity ($10m for HelixNano, which develops vaccine and other anti-infection tech), and Effective Altruism (e.g. $15m for Longview Philanthropy, itself a fundraising org). Donations also probably went to animal welfare organizations and global development, but these were made by a different branch of the FTX Foundation and there’s no clear documentation.

Some of that philanthropic money was distributed through a regrantor program that authorized agents to make grants on their own initiative, with some but not much oversight from FTX. It funded things like the memoirs of someone who worked on Operation Warp Speed, many independent AI safety researchers, and in my case, a project to find or train new research analysts who could do work similar to mine, or assistants to help them.

After the bankruptcy, I waited to be contacted by the FTX estate asking for their money back. Under US bankruptcy law I was outside the 90-day lookback period in which clawbacks are easy, but within the two-year period where they were possible. I did receive one email claiming to be from the estate, but it had a couple of oddities suggesting “scam” so I ignored it, and never received any follow-up. In November 2024, the statute of limitations for clawbacks passed, and with it, any legal claim anyone else had on the money.

For the next few months, I did nothing. Everyone I knew was keeping their money and seemed very confident that this was fine. And all things being equal, I like money as much as the next person.

But I couldn’t stop picturing myself trying to justify the choice to keep the money to a stranger, and those imaginary conversations left me feeling gross. None of my reasons seemed very good. When I finally entertained the world where I returned the money voluntarily, I felt hypothetically proud. So I decided to give it back, or at least away.

“Avoid tummy aches” isn’t exactly a moral principle. Avoiding my tummy aches is especially not a principle I can ask others to follow. But in the course of arguing with my friends who didn’t think I should give away the money, and trying to figure out where I should donate, I eventually figured out the rules I was implicitly following, and what I would ask of other people.

Protecting the Golden Goose

The modern, high-trust, free-market economy is a goose laying golden eggs. It has moved the subsistence poverty rate from 100% to 47%, lowered urban infant mortality from 50% to less than 1% in developed countries. It brings a king’s ransom in embroidery floss directly to my house for a fraction of an hour’s wage.

This is $30, and I’m disgusted because it’s not pre-loaded onto bobbins.

The most important thing in the world after extinction-level threats is to keep this goose happy and productive, because if the goose stops laying, then we don’t have any gold to spend on things like vaccine cold chains or cellular data networks. Every theft gives a little bit of poison to the goose. A norm that you can steal if you have a good reason will kill the goose, and then we will be back to the nasty, brutish, and short lifespans of our agricultural ancestors. This is true even if your reason is really, really, really good.

Given how damaging theft is to the goose, it’s important to keep the incentives to steal as low as possible. One obvious way is to not let thieves keep the money. For most thieves this is enough, because having the money themselves was the whole point. But in this weird case where the theft was at least partially to fund philanthropic projects, it’s important to not spend the money on those projects.

That ship has mostly sailed, of course. Even if I gave back/away all the money FTX gave me, I still did a bunch of work they wanted. Giving the money away doesn’t erase the work, and would violate another principle in the care and feeding of golden geese, that people get to keep what they earned.

But I only spent 80% of the money (some on my own salary, some on researchers I was trialing). The other 20% wasn’t earned by me or anyone else. I could earn it now, with a new project- my old project had wrapped up but my regrantor had given permission to redirect to anything reasonable before the bankruptcy. I have a long backlog of projects; it wouldn’t be hard to just do one and conceptually bill it to FTX. But given that I had FTX’s (indirect) blessing on arbitrary projects that means doing any of them would reward the theft.

(If it seems crazy to you that FTX executives genuinely believed they stole for the greater good and all that altruism wasn’t just a PR stunt, keep in mind that they believed the world was at risk of total annihilation in 5-10 years due to artificial superintelligence. I also know some people who knew some people, and they’re really sure that at least some of the executives were sincere at least at the start.)

Having decided I can’t keep it, where should the money go? Obviously the best place would be the victims of FTX’s theft. The only way I know of to give to them is via the FTX estate. The estate has an email address for people who wish to voluntarily return money but I guess they’re not checking it, because I’ve been emailing them for months with no reply.

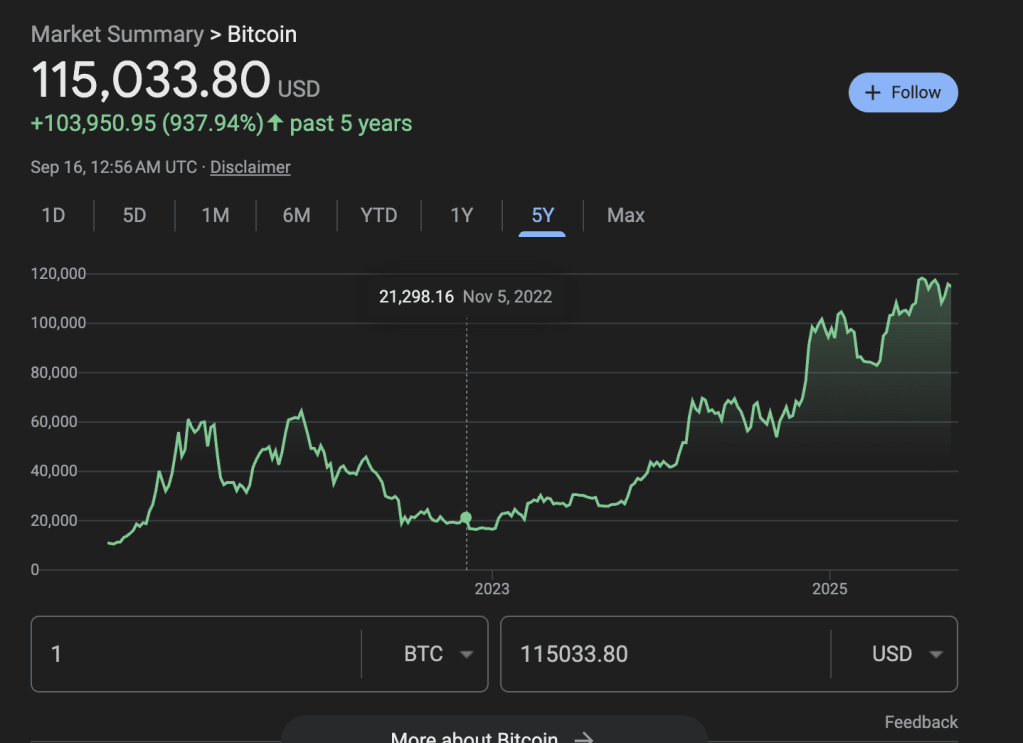

Some of you may argue that the FTX users are already going to be made whole, in fact 120% of whole, because FTX’s investments did well and the estate will be able to pay all the claims. This is technically true, but it uses the valuation of crypto assets at the time of bankruptcy. Since then bitcoin has 6xed; 20% doesn’t begin to cover the loss. It might not even cover inflation + compound interest.

My next choice was to donate to investigative journalism in crypto- if I couldn’t redress crypto theft, maybe I could prevent it. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be anyone who’s good at this, still working, and will accept donations higher than $5/month. You might think, “Surely he would accept larger amounts if offered, even if he doesn’t list it on his website,” but no, my friend tried to give him money months ago, and he refused. And there was no second choice.

If I can’t give it to the victims or prevent future victims, my third choice was wherever it would do the most good, in an area FTX Foundation didn’t value (so as to not reward theft). This is hard because while FTX funded a lot of stupid things, they also covered a long list of good things. I, too, hate AI risk and deadly pandemics. After sampling a bunch of ideas, I eventually settled on Feeding America. Feeding hungry people may not have the highest possible impact, but it’s hard to argue that it’s not helping. FTX never hinted at caring much about American poverty. I don’t know anyone involved with Feeding America, so there’s no possibility of self-enrichment. And 10 years ago, I heard a great podcast on how they used free-market principles to make their food distribution vastly more efficient.

I don’t feel amazing about this choice. I don’t think amazing was an option once the FTX estate declined my offer. But I feel good enough about this, and there’s no good way to optimize when you’re specifically trying to thwart optimizers like the FTX executives. All I can do is make sure I’m living up to my principles and make some people a little less hungry.

The Widow’s Mite Isn’t Worth Very Much

Do I think other people are obligated to give away their FTX grants? The answer is closer to yes than no, but not without complications.

I think people should give back/away FTX money they hadn’t already spent or earned. But I take a liberal definition of spending and earning. If I hadn’t paid my taxes on those grants at the time of the bankruptcy, I’d still consider the taxes already spent, because accepting the money committed me to paying them (although FTX told me I didn’t need to pay taxes on the grant. This is the clearest sign I received that Something Was Wrong with the FTX Foundation, and to my shame, I ignored it as standard Effective Altruism messiness). I know someone who quit their job and moved countries on the assumption that the FTX money would always be there, and while I think that was a stupid decision even absent the fraud, the cost of moving back home and reestablishing her life counts as “already spent.” She might have to give back something, but accepting the grant and assuming its good faith shouldn’t come with a bill.

But it was not random happenstance that it was easy for me to drop my FTX-funded project on a dime when scary rumors started. I work as a freelancer, sometimes balancing many projects from many clients and sometimes having none but my own (which necessitates a healthy cushion of savings). So when the word came down that FTX was at risk and the responsible thing to do was to stop spending their grants, it was just another Tuesday for me to stop their project. To the extent that giving up this money is morally praiseworthy, I think the praise should accrue to the decisions that made giving up the money easy, rather than the actual donation.

This is not a popular belief. Most people’s view on charity is summed up by the biblical story of the widow’s mite, in which a poor widow giving up a small amount at great personal sacrifice is considered more virtuous than large donations from rich men. I can see the ways that’s appealing when trying to judge someone’s character. But even if we’re going to grade people on difficulty, we have to look further back than the last step. If the rich men worked hard and made sacrifices to achieve their wealth, and they chose to invest that money in helping others rather than yachts, that should be recognized (although of course this doesn’t justify hurting others to get that money; I’m talking only about personal sacrifice).

So I think people in my exact position have a strong obligation to give away leftover money from FTX. I think people in the related position of technically having unspent money but finding it too great a hardship to give back shouldn’t ruin their lives by doing so. But I encourage them to think about what they would need to change in their life to make ethical behavior easier.

Thanks

Thanks to the Progress Studies Blog Building Initiative and everyone who argued with me for feedback on this post.

Jason @ 2025-10-03T01:25 (+4)

I think people should give back/away FTX money they hadn’t already spent or earned. But I take a liberal definition of spending and earning.

This sounds reasonable to me, with the caveat that I think the definition should be significantly more liberal for natural persons than for non-profits. By performing work, an individual like Elizabeth incurred a detriment to herself (she could have sold her labor to someone else). Although I don't know the specifics of the person who incurred "the cost of moving back home and reestablishing her life" when FTX exploded, that sounds like a detriment too.

But if a fraudster gives a cancer-research charity $500K, and it spends $500K on cancer research, I don't see any detriment to the charity in the same way. Given that the sole purpose of the charity is to fund cancer research, it's hard to call the funding outlay a detriment. Maybe the charity dropped its funding bar slightly and so repaying the whole $500K would put it in a slightly worse place than if it had ever accepted the fraudster's money in the first place. But disgorging the dirty money doesn't leave the nonprofit holding the bag in nearly the same way as it would leave an individual worker or even a for-profit who exchanged reasonably equivalent value in goods or services.

SummaryBot @ 2025-10-01T16:30 (+1)

Executive summary: The author reflects on what to do with $6,000 of unspent FTX grant money, arguing that since it was funded by theft they cannot keep or “earn” it retroactively, and concludes that returning it to victims (via the estate) or donating it elsewhere is the most principled path, while urging others with similar leftover funds to consider doing likewise.

Key points:

- FTX distributed large philanthropic grants with stolen funds; the author received $33,000, spent most on legitimate work, but still has ~20% unspent.

- Legal obligations to return the money expired in 2024, but the author judged keeping it as morally indefensible, particularly given the principle of protecting high-trust economic norms (the “golden goose”).

- They tried to return the money to the FTX estate but received no response; in their absence, they plan to donate it to Feeding America, a cause outside FTX’s focus and with little risk of self-enrichment.

- The “golden goose” framing emphasizes that allowing theft—even for altruistic reasons—undermines the trust and prosperity enabling large-scale philanthropy in the first place.

- The author distinguishes between already “earned/spent” funds (e.g. salaries, taxes, moving costs) and genuinely unspent money; only the latter should be given away.

- They argue that people who can give up leftover FTX funds without great hardship have a strong obligation to do so, while those facing severe personal costs should instead focus on making future ethical choices easier.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.