Improving wild animal welfare reliably

By Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-15T17:08 (+47)

This post is adapted from an article I published in the Journal of Applied Philosophy. The original article is more detailed, but also more philosophically dense and likely less relevant to EAs.

Epistemic status: confident about the core argument, less about the examples and details.

TL;DR: Almost all suffering in the world today is experienced by wild animals, yet ecosystems are incredibly complex and it's hard to predict what outcomes any particular intervention will have. This post addresses the concern many people have about uncertainty/risk in this cause area by developing a framework for precautionary intervention that weighs ecological risks against welfare benefits. I then identify types of interventions that promise particularly favorable risk/benefit tradeoffs: eliminating the worst diseases, eliminating certain parasites, pursuing more substantial or experimental interventions in urban areas and ecological islands, and promoting high-welfare ecological regimes.

The Problem

Most wild animals suffer and die young due to three systemic factors:

- High reproductive rates (evolution favors producing more offspring than can survive)

- Limited resources

- Antagonistic behaviors (competition, predation, parasitism, disease)

These factors characterize virtually all ecosystems, from rainforests to deserts to urban environments. While humans cause significant harm to wildlife, natural factors contribute far more to wild animal suffering overall.

Why Small-Scale Interventions Aren't Enough

Many proposed interventions - like rescuing injured animals, helping animals in response to natural disasters or reducing bird collisions with buildings - help specific individuals but don't address the systemic factors listed above. As Soryl et al. explain:

All animals naturally reproduce in excess, so while feeding one generation of starving deer might improve their aggregate welfare in the short-term, we cannot expect to achieve the same result indefinitely as future generations come into existence and the demand for food continues to increase ad infinitum.

Preventing the death of some individuals typically just increases competition for others. This is already commonly understood for feral cats and dogs: simply feeding or rescuing animals without population control doesn't improve welfare long-term, but neutering programs that reduce reproductive rates and lower population densities lead to significant welfare improvements.

To effectively reduce wild animal suffering, we need interventions that address the systemic causes of natural suffering, and do so at the ecosystem level.

Two Approaches to Wild Animal Welfare Work

Before diving into the complexity challenge, it's worth distinguishing two different rationales for pursuing wild animal welfare interventions:

Approach 1: Building the movement. Some might argue that small-scale, system-insensitive interventions—like rescuing individual animals or improving urban habitat—should be promoted not because they reliably improve population-level welfare, but because they help build compassion and political will (as argued by Sebo). Many people already feed wild animals not because it helps at a population level, but simply as an expression of compassion. These interventions could be promoted simply to promote the right attitudes. Alternatively, high-risk or questionably effective interventions could be promoted for the purpose of studying their effects, to inform more effective interventions in the future. So both can be understood as stepping stones towards a better future.

I'm sympathetic to these reasons, but they have important limitations. Most effective interventions will need to be different in kind from simple rescue operations, so knowledge gained from small interventions may not translate across. More seriously, there's a risk that compassion and political will will continue to be directed toward ineffective interventions, and the real complexity and risks will not be taken seriously. When people notice predictable failures of well-intentioned but poorly designed interventions, that may undermine support for the field as a whole. I don’t think this undermines approach 1 completely, but approach 1 should at least it should be supplemented with approach 2.

Approach 2: Reliably improving welfare. The alternative is to focus on interventions that we have reason to believe will improve wild animal welfare reliably, even when viewed at the ecosystem level, and despite our currently very limited state of knowledge. This is what the rest of this post explores. When I talk to intelligent and skeptical EAs, I’m often asked: "What interventions can we pursue in the near-term that will actually, reliably help wild animals?" I think this is a great question, and it deserves answers that are honest about the difficulty of this task.

I believe Approach 2 is essential for the long-term credibility and success of this cause area. Nonetheless, the interventions I propose later should be seen as complementary to, not replacing, efforts driven by approach 1. And it’s worth noting that some other suggestions for how to intervene have mixed the two approaches, such as Animal Ethics and Wild Animal Initiative’s proposal to help animals in extreme weather, vaccination programs, and interventions in urban areas.

The Complexity Challenge

Delon and Purves argue that improving wild animal welfare (i.e. with Approach 2) is intractable because:

- Ecosystems are complex with unpredictable interaction effects

- Organisms are highly interrelated, meaning effects can ripple unpredictably

- Repeated disturbances tend to reduce ecosystem resilience, increasing risk of regime shifts (shifts to an entirely new ecosystem-type, i.e. a savannah to desert ecosystem)

- Because of climate change, ecosystems will continue to change, so uncertainties will remain despite efforts to model them.

But the challenge runs even deeper. Even if we could predict the outcomes of interventions, we'd still face major uncertainty in how to evaluate those outcomes:

- Sentience: scientists are still very unsure about which animals are sentient, and what should count as strong evidence of sentience (although Birch's framework is proving quite popular)

- Capacity: we are not sure whether different species differ in their capacity for suffering, and the intensity of their sensation in any given situation (but see RP's work on this)

- Lives worth living: it is not clear how to judge whether wild animals' lives are worth living, such that we are unsure whether growth or declines in populations is good or bad.

These seven sources of uncertainty combine to severely limit our ability to estimate the welfare effects of any intervention. These concerns have been influential in EA discussions, with some arguing that, although wild animal welfare (WAW) is important and neglected, tractability concerns are significant enough to de-prioritize the cause area.

A Framework for Precaution

Many people want to treat this uncertainty not just as creating a state of cluelessness, but as a reason to avoid intervention. But uncertainty is not inherently bad; what is bad is the risk of making things worse. And it is not clear that unexpected impacts will make things worse.

The uncertain balance of welfare in the wild

Although it is commonly thought that natural ecosystems support the flourishing of wild animals, the reality is that most wild animals suffer and die young. Natural selection favors traits that increase species survival, but this is compatible with high mortality and poor welfare for individuals. In many species, evolution has selected for extreme reproductive rates where thousands are born but only a few survive, or for traits that increase reproductive success but cause great pain or death. Whether the wellbeing of wild animals is on expectation positive or negative overall is a matter of debate (1,2,3). If average welfare is low or near zero (I personally think this is more likely with invertebrates, which would otherwise dominate expected-value calculations), unintended consequences are just as likely to have a positive as negative effect. Since most will be unpredictable, it is rational to assign them a neutral expect value, and instead focus on the consequences that we can predict.

Reasons for precaution

Despite this, I think that there are two reasons to be concerned about such high uncertainty, even for consequentialists who are not concerned with causing harm for the greater good:

1. The disturbance-induced welfare penalty: Large or frequent ecological disturbances tend to shift ecosystems toward fast-breeding, short-lived species that generally have lower welfare (1,2). This gives us reason to discount interventions with highly uncertain outcomes.

2. The irreversibility premium: Some ecological changes are very difficult or impossible to reverse (e.g. species extinctions, trophic collapses). These ecological resources are like ‘building blocks’, and with fewer or worse of them there will be fewer options for creating better ecosystems in the future. We should avoid hard-to-reverse changes now in order to preserve our future options. This makes it especially important to preserve ecologically important elements, such as keystone species.

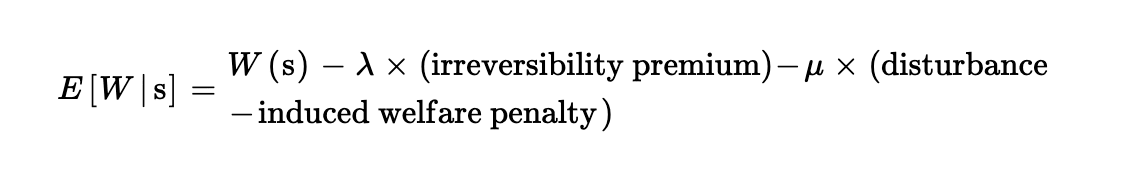

These two features ground precaution in consequentialist terms, and give us reason to favor interventions where ecological risks are low relative to expected welfare benefits. Put differently, 'precaution' in this sense denotes a sensitivity to the costs of irreversible and disturbance-induced changes, while following an expected-value approach. Expected welfare can thus be formalized as follows, for a given intervention:

Where W is the expected welfare benefits given action s, λ is the risk of causing irreversible ecological changes, and μ is a more general measure of the risk of ecological disturbance. Quantifying the irreversibility premium and the disturbance-induced welfare penalty is beyond the scope of this article, and is an important area for future research. Nonetheless, the equation makes clear that we should favor interventions where the degree of ecological risk is low relative to the welfare benefits, especially where there is a risk of irreversible changes.

This should not rule out interventions completely: despite alarming rates of biodiversity loss, we still live in a world with a substantial amount of ecological resources, not all of which are likely to be necessary for the future creation of flourishing ecosystems. But the irreversibility premium + disturbance-induced welfare penalty do make high-risk interventions harder to defend. For example, the proposal to eradicate most predator species clearly involves an unacceptably high level of risk, at least if carried out in the foreseeable future, since the resulting disturbances would drastically reduce our options for compassionate intervention in the future, and certainly cause a substantial demographic shift to species with fast life history strategies.

Promising Near-Term Interventions

But with this framework, several categories of intervention do seem defensible. Unlike previous proposals, the categories below are specifically chosen because they target the systemic causes of suffering (high reproductive rates, limited resources, or antagonistic behaviors) while maintaining a favorable ratio of ecological risks to welfare benefits.

7.1 Targeting the Worst Suffering (certain diseases)

While all wild animal populations face limiting factors, some cause far more suffering than others. The worst diseases - like chronic wasting disease (15-34 months of neurological symptoms), sarcoptic mange (chronic intense itching and infections), or myxomatosis (severe tumors and convulsions over 7-30 days) - may be among the worst sources of suffering in nature.

We could identify the most severe diseases through research and target them with vaccination campaigns. Yes, eliminating a disease would lead to population growth until another factor limits the population - but since it was such an unusually severe limiting factor, the net effect is likely to be positive. Since such campaigns would only affect specific diseases, the ecological risks would be relatively contained. It's also worth noting that rabies vaccination programs have already been implemented in populations of wild animals with relatively small effects (1, 2).

7.2 Eliminating 'Redundant' Suffering (certain parasites)

Some species cause significant suffering while playing minor ecological roles. The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) has received significant attention on the EA Forum as a candidate for eradication. This parasitic fly lays eggs in wounds of mammals and birds, and the hatching larvae eat the host alive, causing extreme suffering to hundreds of millions of animals annually. It's already been successfully eradicated from North and Central America. However, the screwworm interacts with many species beyond just its host during its life cycle, which introduces greater ecological complexity and risk.

A potentially lower-risk example might be the warble fly (Hypoderma), which burrows under the skin of cattle and deer, causing great discomfort, yet rarely kills its host. The warble fly is small in biomass, host-specific (so doesn't greatly affect other species), and has more limited interactions beyond its host-parasite relationship. Although it does reduce the grazing and reproductive activity of hosts, these effects are comparatively minor and could be offset with non-invasive fertility control. Since the warble fly has been effectively eradicated in domesticated populations, primarily with insecticides, without any ecosystem-level cascades, we have good reason to suspect that its eradication in wilderness areas might also have minor ecological consequences. For wild populations, other methods would need to be developed that don't require close contact, such as oral vaccines or gene drives. Both methods involve ecological risks due to their relative novelty and the different ecological context, but given the harm the warble fly causes, such risks are probably worth taking on.

7.3 Urban Interventions

Interventions in urban areas can be treated as lower in risk for several reasons. They:

- Are already heavily disturbed, so the remaining ecosystems tend to be less at risk of regime shifts

- Contain fewer endemic species (so affected species are less likely to go extinct)

- Contain more generalist species (species that can fill different niches) that can better adapt to disturbances

- Tend to have lower biodiversity, making outcomes more predictable

This means that more ambitious interventions become justified: fertility control, disease protection for more species, food/shelter provision, elimination of particularly harmful species - and ideally a combination of the above. These should still be preceded by research and with an eye system-level effects, but the bar for justification is lower.

7.4 Ecological Islands

Ecological islands are areas sharply separated by geography (actual islands, lakes) or barriers (fences), but are otherwise not ecologically unique (the same ecosystem exists elsewhere). They are currently used (in New Zealand & Australia) as conservation areas free of invasive species. But the same concept could be used to test high-risk WAW interventions!

With ecological islands:

- Interventions (such as gene drives) would be less likely to spill over into other areas

- Since the ecosystem has analogues elsewhere, there is low risk of causing species to go completely extinct

- Data from such experiments would inform future interventions in broader contexts.

But:

- Ecological islands don't exist for all species. This is most clearly true for marine, migratory, or flying animals

- Uncertainty can re-emerge when scaling interventions to wider areas

Still, I think ecological islands could be incredibly valuable to help us test technologies like gene drives and develop models.

7.5 Promoting High-Welfare Ecosystem States

Some management decisions involve shifting entire ecosystems between states, such as ecological restoration or desert greening. When restoring a previous ecosystem or reproducing one that exists elsewhere, ecological uncertainty is relatively low. And often this is done anyway for ecological or sustainability reasons. Yet different ecological regimes can contain vastly different levels of wellbeing due to varying proportions of species with different life-history strategies.

If the science of animal consciousness and WAW progresses as expected, we may soon be able to estimate which ecosystem states have higher welfare. This might not require precise estimations - if ecosystems differ greatly, we might be able to estimate this even with quite incomplete information. Decisions to restoration or transform ecosystems could then involve high risk, but extremely high expected reward, such that they could be justified even within the form of precaution I've argued for.

What About Gene Drives?

Gene drives have received attention in EA for their potential to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitoes and reduce suffering in other contexts. In a nutshell (more detail here), CRISPR-based endonuclease drives bias genetic inheritance by prompting cells to copy the drive element to the homologous chromosome during sexual reproduction. In effect, this means that it is almost always inherited, instead of having a 50% chance like other genes. By attaching any other gene to a drive element, even disadvantageous traits (such as lower fertility, lower aggression, or lower toxicity) can be made to spread through wild populations.

Until recently, gene drives seemed too risky for near-term use, due to their tendency to spread. But new developments are changing this:

- Reversal drives can undo gene-drive-mediated changes (though not necessarily the ecological side-effects)

- Daisy-chain drives spread quickly but terminate after a set number of generations

- Underdominance drives require critical mass to spread, so unintended dispersal (i.e. where a few escape an ecological island) is unlikely.

If gene drives start with small-scale, contained field trials before scaling up, their benefits might outweigh ecological risks. This seems especially promising as a method of fertility control (as proposed by Johannsen) or to eliminate specific parasites.

Caveats and Future Work

The interventions I've outlined are not all feasible today. Many require technology development or better ecological understanding. But it's foreseeable that they could be implemented in the near-term if they were treated as research priorities. This reinforces why the broader field-building work being done by organizations like Wild Animal Initiative and Animal Ethics is so important.

To make this precautionary framework more useful in practice, research on the following topics would be of extremely high value:

- Estimating differences in average welfare between species

- Estimating the future opportunity costs of species extinctions or other irreversible changes

- Modelling how disturbances affect species composition and welfare.

Why not decrease nature? Some (most notably Brian Tomasik) think that nature is so bad that intervening is the most high-value option. I think this is possible, but just very hard to know (see Michael Plant's critique of this view and Brian Tomasik's response). Given the risk of being wrong, and that it's not a very politically palatable policy, I think that improvement is probably the better option.

Conclusion

I've tried to argue that wild animal suffering needs to be understood as primarily a system-level phenomenon, and any attempts to address it need to be mindful of its systemic causes. I've also argued that we should be honest about the great uncertainties plaguing WAW interventions, and that high-risk interventions risk causing irreversible changes, or resulting in more fast-breeding, short-lived species. Still, given the scale of suffering in nature, precautionary intervention should be possible.

I haven't been able to say exactly how precautious we should be, because I can't quantify the cost of losing ecological resources such as species, or exactly how likely an intervention is to cause disturbances which in turn increase the proportion of fast-breeding species. Future research should prioritize these questions.

Nonetheless, we can begin by prioritizing interventions that have the best benefit:ecological-risk ratio. I've suggested that this means focusing on: 1) the very worst kinds of suffering (certain diseases); 2) the most ecologically redundant suffering (certain parasites): 3) more experimental approaches in urban areas and 4) ecological islands; and 5) promoting more high-welfare ecological regimes, if we can first say with some degree of confidence that one ecosystem type is better than another.

Michael St Jules 🔸 @ 2026-01-15T21:55 (+8)

Thanks for sharing!

We could identify the most severe diseases through research and target them with vaccination campaigns. Yes, eliminating a disease would lead to population growth until another factor limits the population - but since it was such an unusually severe limiting factor, the net effect is likely to be positive.

This is interesting and seems possible to me, but I'd probably want to look more into any particular case and see population modelling to verify the logic more generally.

If this does work, I wonder if we'd have a general and reliable path forward for reducing wild animal suffering (whether disease or another cause, it sounds like you're more agnostic about it being diseases in the paper): just iteratively and incrementally reduce the causes of suffering in a population, roughly in order from the most severe (worst conditional on their occurrence[1]) to the mildest.

- ^

However, the worst conditional on their occurrrence could be rare enough that this wouldn't look cost-effective. In that case, we might look for another animal population where it does look cost-effective to reduce the most severe cause of suffering.

abrahamrowe @ 2026-01-15T22:05 (+10)

I feel less confident in this specific approach — I think downstream effects are just often very contingent. It's easy to imagine scenarios like: eliminate very bad disease 1, population goes up, now very bad disease 2 emerges or is transmitted from some other population because contact occurs, etc.

I suppose this could be less of an issue for the very worst diseases/issues, etc., but I suspect those by their nature are less common (e.g. could be self-limiting, etc), and it seems like the method would only work insofar as changing population levels, etc. doesn't increase the risk of novel worse things, which seems only possible for the very worst things.

That being said I am very sympathetic to just trying more things, at least for some animals, especially vaccinations.

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-16T09:22 (+3)

Thanks for this point!

My argument is that while such outcomes are possible, the outcomes of the opposite effect are also possible, and often there just doesn't seem reason to assume one to be more likely than the other (this is in simplest terms what people mean when they talk about cluelessness). Given that, I think it makes sense to assume the effects which we cannot predict are on expectation neutral (most likely, they will be a mix of good and bad) and then pursue it if the effects we can predict are clearly good.

So for example, treating chronic wasting disease in deer will surely affect populations of very small mammals, reptiles, and insects in subtle but nonetheless large ways, due to the numbers of these species. But it's going to be a mix of benefits and harms, which are incredibly hard to predict. The benefit for the deer, however, is really certain, so if it can be done without great environmental disruption, then I'd say the expected value is pretty good.

mal_graham🔸 @ 2026-01-17T14:47 (+4)

I've been thinking about this approach since last year, and haven't had time to prioritize it to do detailed work on a framework, but I have some initial thoughts. I think you're right that, if you're comfortable with that sort of cluelessness, this kind of thing is relatively safe to do (although as @Michael St Jules 🔸 notes, I'd also want to do some proper population modeling in a highly studied ecosystem to get some grounding for the idea).

But I think you can actually do better than focusing on only the very worst diseases depending on population parameters. For example, in populations that are top-down regulated (i.e., the population size is held under the carrying capacity of the resource by an external factor), you would not expect increases in starvation as a result of removing a disease (caveat: if that disease *is* the top down regulator, than you would have a problem - which unfortunately is the case in many CWD contexts). So then the disease doesn't need to be worse than both starvation and predation, say, but rather just worse than predation. The population size would equilibriate somewhere a bit higher, but the top-down regulation creates a buffer between population size and resource carrying capacity, and at high enough predation pressures you might reasonably expect almost no population increase.

So I think in an ideal case, you'd identify (1) a high suffering disease that (2) affects a population primarily controlled by intense predation pressure in (3) a predator that mainly eats the target population (so the increases in predator population sizes don't affect other animals, who aren't having a disease treated and for whom this would just represent an increase in suffering).

Of course, if you have a population with high predation pressure, the target population probably dies very quickly after getting the disease, so the suffering caused by the disease might not be very long in duration. But if its a really awful disease that could still be a lot of suffering.

I don't think anyone's done a scan of the literature for diseases with these properties, and I doubt you'd easily find a perfect case -- most populations are a mixture of top-down and bottom-up regulation. But I also think that probably my few hours of playing around with these ideas on the side of my other work are not likely to be the final word on the question :) so I'm optimistic someone spending a lot more time with this could identify other "ecological profiles" of diseases that make them "safer" in indirect effects terms to work on than others (I think there's some things to say about bottom-up regulated populations as well, for example -- probably there you would want a disease that is a lot worse than starvation).

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-17T15:12 (+1)

Hey Mal, this is a great point, I completely agree. The disease doesn't have to be worse than all possible ways of dying if you know that the counterfactual is likely to be a particular mid-intensity harm. Although the welfare gains should still be significant in order to justify the ecological risks.

mal_graham🔸 @ 2026-01-17T14:57 (+1)

Re: your footnote: I think this depends heavily on how severe we are talking. I don't have a strong opinion, because I really think no one has looked at it, about how much more severe things can get from disease than from something like keel bone fractures. A priori it doesn't seem unreasonable to assume that the artificial conditions of factory farming enable a chicken to live in pain much longer, and therefore have higher overall suffering, than we would ever see in the wild -- but I'm not that confident in that idea, so it would be good to look at more diseases. The point being that a severe enough disease could still be worth working on in dalys/dollar terms even if it doesn't affect that many individuals, and that would also make it more ecologically inert in many cases (since changing the circumstances of very large numbers of animals seems riskier).

WAI facilitated a grant from Coefficient (then OP) years ago to look at disease severity; they came out with a few papers recently here and here. As is perhaps unsurprising, but disappointing, much of the research on disease in wildlife doesn't provide enough info to do a good job estimating the welfare burden. But the high scoring bacterial zoonoses in the first paper could be a good place to start a research project attempting to better assess the severity and numerosity compared to FAW conditions (as a cost effectiveness bar).

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-16T09:23 (+1)

Thanks Michael! And definitely, all of these interventions should ideally be pursued only after trying to predict as many of the effects as possible. I gave a bit more of an answer on this point below.

I can also imagine incrementally moving down the ladder of worst harms... but I expect things will get harder as interventions become more pervasive, and at some point we would need more comprehensive modelling or to really think about how we want to shape the ecosystem as a whole.

diegoexposito @ 2026-01-16T08:51 (+2)

Beyond thanking you for writing this paper (which I have been waiting for for months), I need to thank you for summarizing and disseminating it. I think moral and political philosophers hardly ever do this, which often leads to their work not being read outside academic circles.

Now, I’m curious to hear your view on the main bottleneck preventing these solutions from being implemented. I.e., if you were to start an organization, what would you focus on? Policy, actionable research, targeted attitude change...?

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-16T09:10 (+1)

Thanks Diego!

Yea, I largely disregarded political/cultural tractability in this analysis, as well as cost. So while I would LOVE to see ecological islands created for animal welfare, this would be prohibitively expensive for activists, and it's hard to imagine governments deciding to do it anytime soon. I think the main purpose of the paper was to show that positive WAW interventions are feasible (and desirable) in the near-term future, even if still all-things-considered unlikely.

That said, I think the other interventions would be easier on this dimensions. Most ordinary people do sympathize with animals suffering particularly severe diseases or nasty parasites. We don't place as much value on these the way we do for other species. So if this could be shown to be cheap, I think people might support it, particularly if it were part of a rewilding project (where people think they have more responsibility for the animals) or also affect farm animals. So to be clear, I do think the work of Screwworm Free Future is a great idea and totally worth pursuing!

Similarly, people seem to sympathize with urban animals a lot more, and we already see urban planning projects taking animal welfare into account (I think that dovecotes used to reduce urban pigeon reproduction, for example, are very likely to improve welfare).

And for promoting high-welfare ecosystems... this would be tractable if it was something people were tempted to do for other reasons. For example, if desert greening improves welfare, then we should encourage desert greening. If it doesn't, then we can leverage reasons for opposing it e.g. it not being natural.

At the end of the day, I think the main bottleneck is just that we're not trying enough things (but I think Rethink Priorities is looking to change this).

David Mathers🔸 @ 2026-01-15T20:11 (+2)

"A potentially lower-risk example might be the warble fly (Hypoderma), which burrows under the skin of cattle and deer, causing great discomfort, yet rarely kills its host. The warble fly is small in biomass, host-specific (so doesn't greatly affect other species), and has more limited interactions beyond its host-parasite relationship. Although it does reduce the grazing and reproductive activity of hosts, these effects are comparatively minor and could be offset with non-invasive fertility control"

Remember that it's not uncontroversial that it is preferable to have less animals at higher welfare level, rather than more animals at lower welfare level. Where welfare is net positive either way, some population ethicists are going to say having more animals at a lower level of welfare can be better than less at a higher level of welfare. See for example: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/utilitas/article/what-should-we-agree-on-about-the-repugnant-conclusion/EB52C686BAFEF490CE37043A0A3DD075 But also, even on critical level views designed to BLOCK the repugnant conclusion, it can sometimes be better to have more welfare subjects at a lower but still positive level of welfare, then less subjects at a higher level of welfare. So maybe it's better to have more deer even when some of them have warble fly, than to have less deer, but none of them have warble fly.

Jim Buhler @ 2026-01-15T22:26 (+3)

...if you think welfare is net positive either way, yes. This seems like a tough case to make. I see how one can opt for agnosticism over believing net negative but I doubt there exists anything remotely close to a good case that WAW currently is net positive (and not just highly uncertain).

David Mathers🔸 @ 2026-01-16T16:58 (+2)

I agree, it is unclear whether welfare is actually positive.

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-16T09:32 (+1)

You're right that this is philosophically controversial. I find the debate interesting, and don't mean to dismiss it - but I also find it incredibly difficult.

The challenge I see is whether such philosophical debates, ones that are totally unresolved, should inform our practical thinking and policy recommendations. Because within ordinary, day-to-day thinking, the idea that "it's preferable to have more beings with lower welfare" is controversial. If you were committed to this view, and thought insects have positive welfare (I agree with @Jim Buhler that this isn't clear), then it seems you would also have to say that the Against Malaria Foundation is doing overall bad work. Maybe you're willing to bite that bullet - but my own inclination is to assume a more common-sense view, even if philosophically incoherent, until there is something closer to a consensus on this topic.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2026-01-16T16:58 (+4)

Those are fair point in themselves, but I don't think "less deer is fine, so long as they have a higher standard of living" has anything like the same commonsense standing as "we should protect people from malaria with insecticide even if the insecticide hurts insects".

And it's not clear to me that assuming less deer is fine in itself even if their lives are good is avoiding taking a stance on the intractable philosophical debate, rather than just implicitly taking one side of it.

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-17T12:13 (+3)

Oh I see I'd misunderstood your point. I thought you were concerned about lowering the number of warble flies. This policy wouldn't lower the number of deer - it would maintain the population at the same level. This is for the sake of avoiding unwanted ecological effects. If you think it's better to have more deer, fair enough - but then you've got to weigh that against the very uncertain ecological consequences of having more deer (probably something like what happened in Yellowstone Nationa Park: fewer young trees, more open fields, fewer animals that depend on those trees, more erosion etc)

David Mathers🔸 @ 2026-01-17T12:15 (+3)

Oh, ok, I agree, if the number of deer is the same after as counterfactually, it seems plausibly net positive yes.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2026-01-16T17:04 (+2)

Also, it's certainly not common sense that it is always better to have less beings with higher welfare. It's not common sense that a world with 10 incredibly happy people is better than one with a billion very slightly less happy people.

And not every theory that avoids the repugnant conclusion delivers this result, either.

Tristan Katz @ 2026-01-17T12:08 (+1)

No - and I wasn't meaning to say that less beings with higher welfare is always better. Like I said, I don't think the common sense view will be philosophically satisfying.

But a second common sense view is: if there are some beings whose existence depends on harming others, then them not coming into existence is preferable.

I expect you can find some counter-example to that, but I think most people will believe this in most situations (and certainly those involving parasites).