Should we aim for flourishing over mere survival? The Better Futures series.

By William_MacAskill, Forethought @ 2025-08-04T14:27 (+166)

Today, Forethought and I are releasing an essay series called Better Futures, here.[1] It’s been something like eight years in the making, so I’m pretty happy it’s finally out! It asks: when looking to the future, should we focus on surviving, or on flourishing?

In practice at least, future-oriented altruists tend to focus on ensuring we survive (or are not permanently disempowered by some valueless AIs). But maybe we should focus on future flourishing, instead.

Why?

Well, even if we survive, we probably just get a future that’s a small fraction as good as it could have been. We could, instead, try to help guide society to be on track to a truly wonderful future.

That is, I think there’s more at stake when it comes to flourishing than when it comes to survival. So maybe that should be our main focus.

The whole essay series is out today. But I’ll post summaries of each essay over the course of the next couple of weeks. And the first episode of Forethought’s video podcast is on the topic, and out now, too.

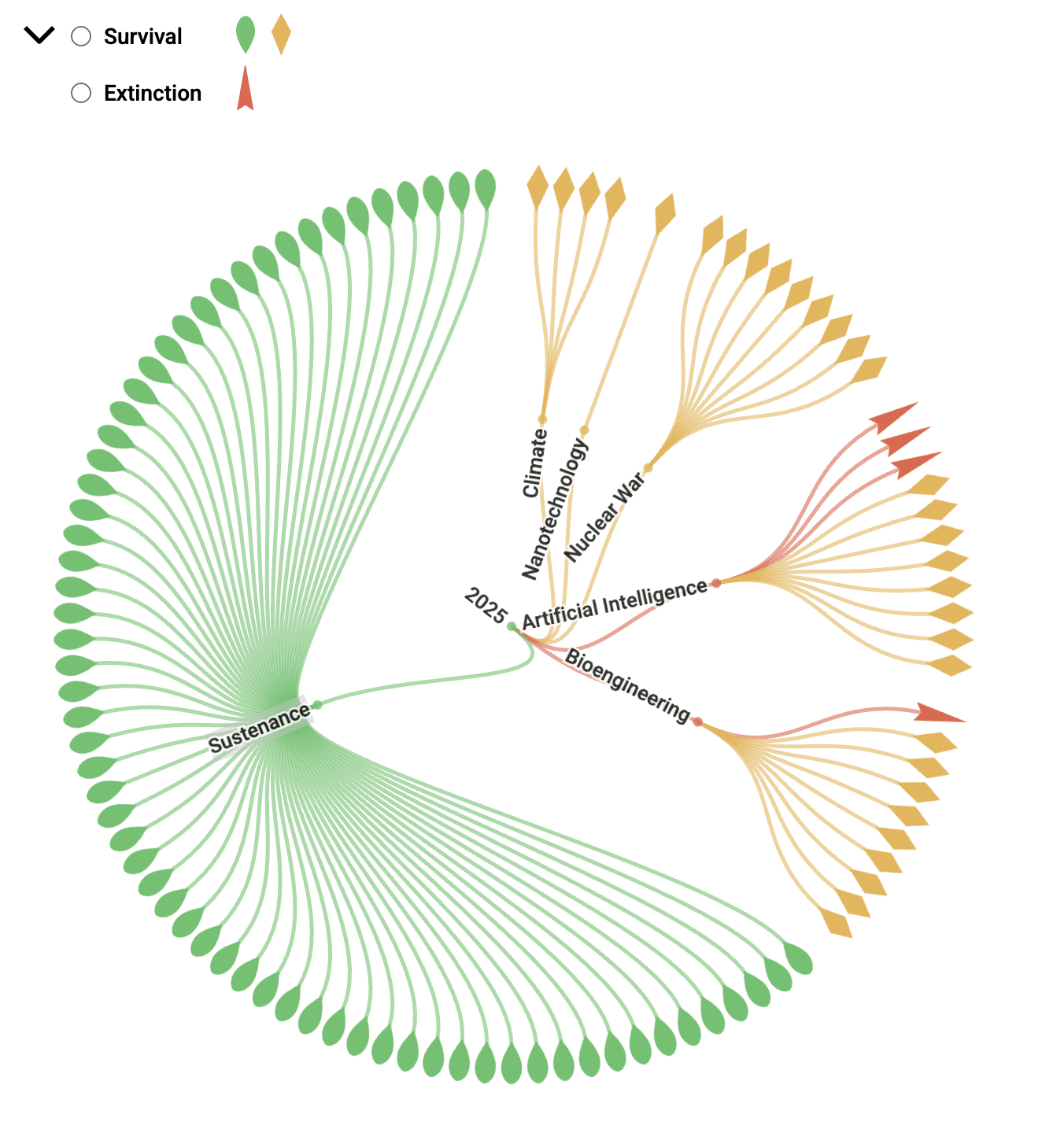

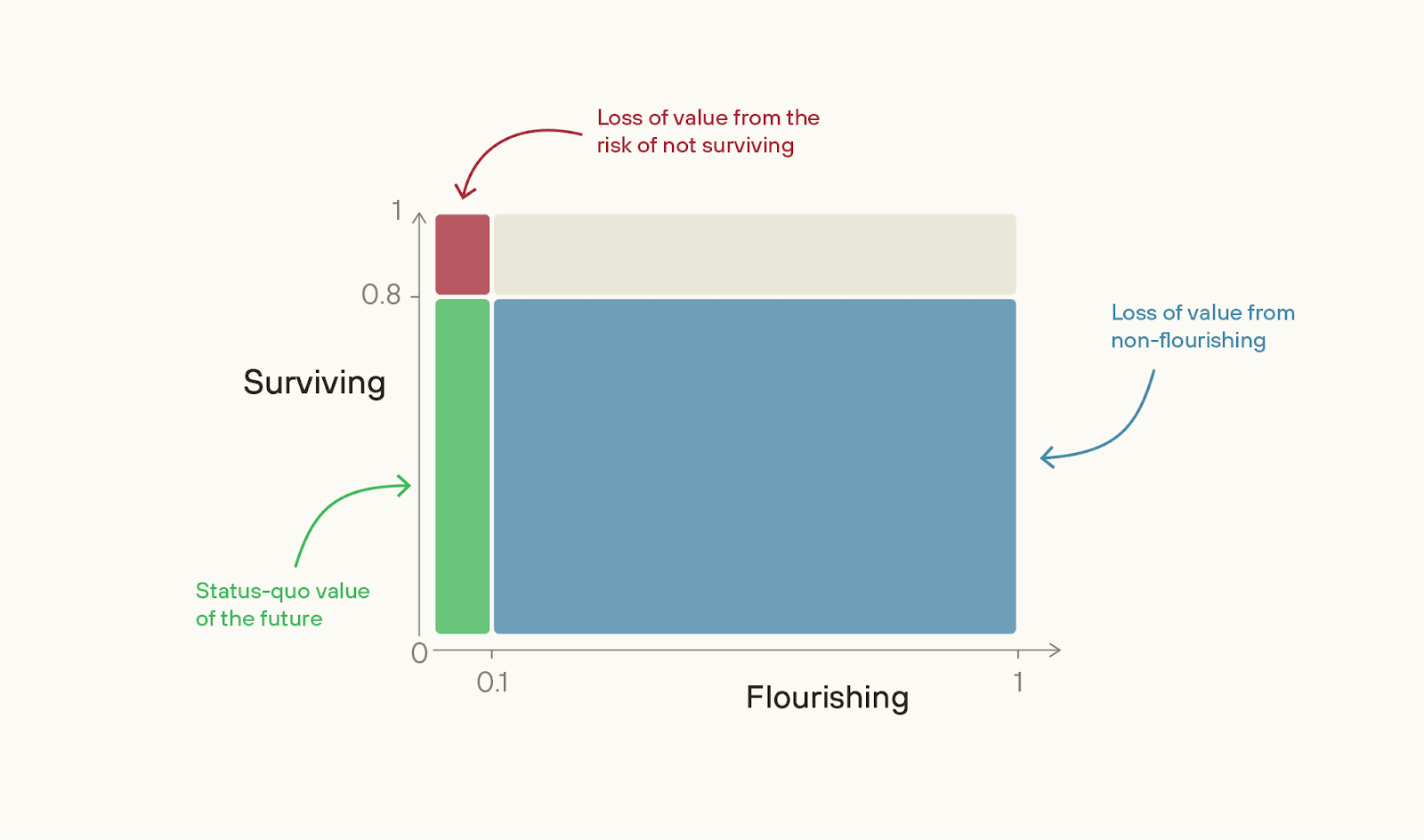

The first essay is Introducing Better Futures: along with the supplement, it gives the basic case for focusing on trying to make the future wonderful, rather than just ensuring we get any ok future at all. It’s based on a simple two-factor model: that the value of the future is the product of our chance of “Surviving” and of the value of the future, if we do Survive, i.e. our “Flourishing”.

(“not-Surviving”, here, means anything that locks us into a near-0 value future in the near-term: extinction from a bio-catastrophe counts but if valueless superintelligence disempowers us without causing human extinction, that counts, too. I think this is how “existential catastrophe” is often used in practice.)

The key thought is: maybe we’re closer to the “ceiling” on Survival than we are to the “ceiling” of Flourishing.

Most people (though not everyone) thinks we’re much more likely than not to Survive this century. Metaculus puts *extinction* risk at about 4%; a survey of superforecasters put it at 1%. Toby Ord put total existential risk this century at 16%.

Chart from The Possible Worlds Tree.

In contrast, what’s the value of Flourishing? I.e. if near-term extinction is 0, what % of the value of a best feasible future should we expect to achieve? In the next two essays that follow, Fin Moorhouse and I argue that it’s low.

And if we are farther from the ceiling on Flourishing, then the size of the problem of non-Flourishing is much larger than the size of the problem of the risk of not-Surviving.

To illustrate: suppose our Survival chance this century is 80%, but the value of the future conditional on survival is only 10%.

If so, then the problem of non-Flourishing is 36x greater in scale than the problem of not-Surviving.

(If you have a very high “p(doom)” then this argument doesn’t go through, and the essay series will be less interesting to you.)

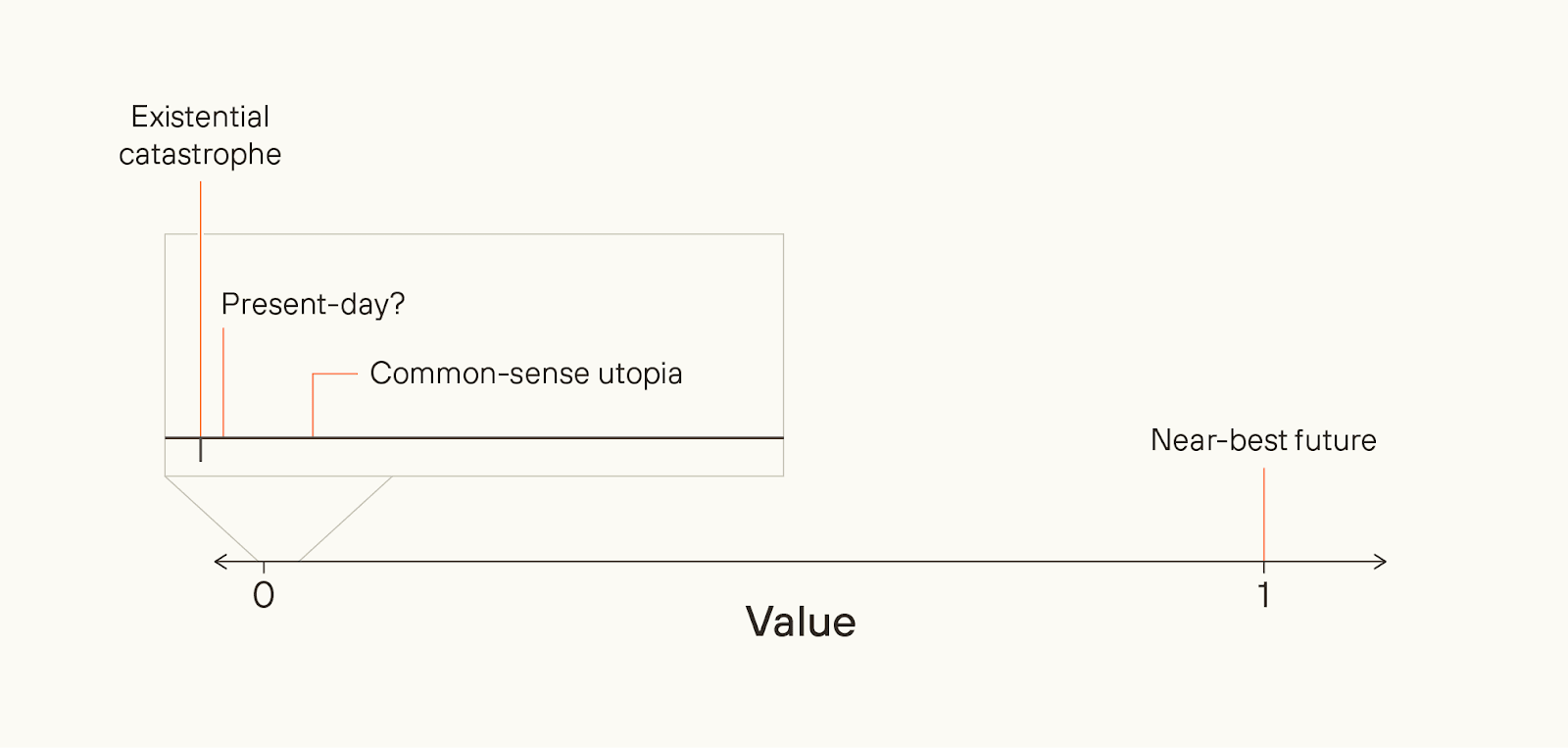

The importance of Flourishing can be hard to think clearly about, because the absolute value of the future could be so high while we achieve only a small fraction of what is possible. But it’s the fraction of value achieved that matters. Given how I define quantities of value, it’s just as important to move from a 50% to 60%-value future as it is to move from a 0% to 10%-value future.

We might even achieve a world that’s common-sensically utopian, while still missing out on almost all possible value.

In medieval myth, there’s a conception of utopia called “Cockaigne” - a land of plenty, where everyone stays young, and you could eat as much food and have as much sex as you like.

We in rich countries today live in societies that medieval peasants would probably regard as Cockaigne, now. But we’re very, very far from a perfect society. Similarly, what we might think of as utopia, today, could nonetheless barely scrape the surface of what is possible.

All things considered, I think there’s quite a lot more at stake when it comes to Flourishing than when it comes to Surviving.

I think that Flourishing is likely more neglected, too. The basic reason is that the latent desire to Survive (in this sense) is much stronger than the latent desire to Flourish. Most people really don’t want to die, or to be disempowered in their lifetimes. So, for existential risk to be high, there has to be some truly major failure of rationality going on.

For example, those in control of superintelligent AI (and their employees) would have to be deluded about the risk they are facing, or have unusual preferences such that they're willing to gamble with their lives in exchange for a bit more power. Alternatively, look at the United States’ aggregate willingness to pay to avoid a 0.1 percentage point chance of a catastrophe that killed everyone - it’s over $1 trillion. Warning shots could at least partially unleash that latent desire, unlocking enormous societal attention.

In contrast, how much latent desire is there to make sure that people in thousands of years’ time haven’t made some subtle but important moral mistake? Not much. Society could be clearly on track to make some major moral errors, and simply not care that it will do so.

Even among the effective altruist (and adjacent) community, most of the focus is on Surviving rather than Flourishing. AI safety and biorisk reduction have, thankfully, gotten a lot more attention and investment in the last few years; but as they do, their comparative neglectedness declines.

The tractability of better futures work is much less clear; if the argument falls down, it falls down here. But I think we should at least try to find out how tractable the best interventions in this area are. A decade ago, work on AI safety and biorisk mitigation looked incredibly intractable. But concerted effort *made* the areas tractable.

I think we’ll want to do the same on a host of other areas — including AI-enabled human coups; AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination; what character and personality we want advanced AI to have; what legal rights AIs should have; the governance of projects to build superintelligence; deep space governance, and more.

On a final note, here are a few warning labels for the series as a whole.

First, the essays tend to use moral realist language - e.g. talking about a “correct” ethics. But most of the arguments port over - you can just translate into whatever language you prefer, e.g. “what I would think about ethics given ideal reflection”.

Second, I’m only talking about one part of ethics - namely, what’s best for the long-term future, or what I sometimes call “cosmic ethics”. So, I don’t talk about some obvious reasons for wanting to prevent near-term catastrophes - like, not wanting yourself and all your loved ones to die. But I’m not saying that those aren’t important moral reasons.

Third, thinking about making the future better can sometimes seem creepily Utopian. I think that’s a real worry - some of the Utopian movements of the 20th century were extraordinarily harmful. And I think it should make us particularly wary of proposals for better futures that are based on some narrow conception of an ideal future. Given how much moral progress we should hope to make, we should assume we have almost no idea what the best feasible futures would look like.

I’m instead in favour of what I’ve been calling viatopia, which is a state of the world where society can guide itself towards near-best outcomes, whatever they may be. Plausibly, viatopia is a state of society where existential risk is very low, where many different moral points of view can flourish, where many possible futures are still open to us, and where major decisions are made via thoughtful, reflective processes.

From my point of view, the key priority in the world today is to get us closer to viatopia, not to some particular narrow end-state. I don’t discuss the concept of viatopia further in this series, but I hope to write more about it in the future.

- ^

This series was far from a solo effort. Fin Moorhouse is a co-author on two of the essays, and Phil Trammell is a co-author on the Basic Case for Better Futures supplement.

And there was a lot of help from the wider Forethought team (Max Dalton, Rose Hadshar, Lizka Vaintrob, Tom Davidson, Amrit Sidhu-Brar), as well as a huge number of commentators.

JackM @ 2025-08-05T00:58 (+25)

It's worth noting that it's realistically possible for surviving to be bad, whereas promoting flourishing is much more robustly good.

Survival is only good if the future it enables is good. This may not be the case. Two plausible examples:

- Wild animals generally live bad lives and we never solve this: it's quite plausible that most animals have bad lives. Animals considerably outnumber humans so I'd say we probably live in a negative world now. Surviving being good may then bank on us solving the problem of wild animal suffering. We don't currently have great ideas on how to solve wild animal suffering, so making sure we survive might be a bit of a gamble.

- We create suffering digital minds: The experience of digital minds may dominate far future EV calculations given how many might be created. We can't currently be confident they will have good lives—we don't understand consciousness well enough. Furthermore, the futures where we create digital minds may be the ones where we wanted to “use” them, which could mean them suffering.

Survival could still be great of course. Maybe we'll solve wild animal suffering, or we'll have so many humans with good lives that this will outweigh it. Maybe we'll make flourishing digital minds. But I wanted to flag this asymmetry between promoting survival and promoting flourishing, as the latter is considerably more robust.

Ben_West🔸 @ 2025-08-05T22:00 (+10)

I think this is an important point, but my experience is that when you try to put it into practice things become substantially more complex. E.g. in the podcast Will talks about how it might be important to give digital beings rights to protect them from being harmed, but the downside of doing so is that humans would effectively become immediately disempowered because we would be so dramatically outnumbered by digital beings.

It generally seems hard to find interventions which are robustly likely to create flourishing (indeed, "cause humanity to not go extinct" often seems like one of the most robust interventions!).

JackM @ 2025-08-06T00:19 (+10)

A lot of people would argue a world full of happy digital beings is a flourishing future, even if they outnumber and disempower humans. This falls out of an anti-speciesist viewpoint.

Here is Peter Singer commenting on a similar scenario in a conversation with Tyler Cowen:

COWEN: Well, take the Bernard Williams question, which I think you’ve written about. Let’s say that aliens are coming to Earth, and they may do away with us, and we may have reason to believe they could be happier here on Earth than what we can do with Earth. I don’t think I know any utilitarians who would sign up to fight with the aliens, no matter what their moral theory would be.

SINGER: Okay, you’ve just met one.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-06T09:49 (+1)

This is pretty chilling to me, actually. Singer is openly supporting genocide here, at least in theory. (There are also shades of "well, it was ok to push out all those Native Americans because we could use the land to support a bigger population.)

JackM @ 2025-08-06T12:38 (+3)

I'm not an expert, but I think you've misused the term genocide here.

The UN Definition of Genocide (1948 Genocide Convention, Article II):

"Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:(a) Killing members of the group;

...

Putting aside that homo sapiens isn't one of the protected groups, the "as such" is commonly interpreted to mean that the victim must be targeted because of their membership of that group and not some incidental reason. In the Singer case, he wouldn't be targeting humans because they are humans, he'd be targeting them on account of wanting to promote total utility. In a scenario where the aliens aren't happier, he would fight the aliens.

I'm probably just missing your point here, and what you're actually getting at is that Singer's view is simply abhorrent. Maybe, but if you read the full exchange, what he's saying is that, in a war, he would not choose a side based on species but instead based on what would promote the intrinsic good. Importantly, I don't think he says he would invite/start the war, only how he would act in a scenario where a war is inevitable.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-06T12:55 (+6)

Even under that definition, I think the aliens sound to me like they intend to eliminate humans, albeit as a means to an end, not an end to itself. If the Armenian genocide happened to be more about securing a strong Turkish state than any sort of Nazi-style belief that the existence of Armenians was itself undesirable because they were someone inherently evil, it wouldn't mean it wasn't genocide. (Not sure what the actual truth is on that.) But yes, I am more bothered about it being abhorrent than about whether it meets the vague legal definition of the word "genocide" given by the UN. (Vague because, what is it to destroy "in part"? If a racist kills one person because of their race is that an attempt to destroy a race "in part" and so genocide?)

"Importantly, I don't think he says he would invite/start the war, only how he would act in a scenario where a war is inevitable." If someone signed up to fight a war of extermination against Native Americans in 1800 after the war already started, I'm not sure "the war was already inevitable" would be much of a defence.

JackM @ 2025-08-06T15:00 (+5)

We're just getting into the standard utilitarian vs deontology argument. Singer may just double down and say—just because you feel it's abhorrent, doesn't mean it is.

There are examples of things that seem abhorrent from a deontological perspective, but good from a utilitarian perspective, and that people are generally in favor of. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are perhaps the clearest case.

Personally, I think utilitarianism is the best moral theory we have, but I have some moral uncertainty and so factor in deontological reasoning into how I act. In other words, if something seems like an atrocity, I would have to be very confident that we'd get a lot of payoff to be in favor of it. In the alien example, I think it is baked in that we are pretty much certain it would be better for the aliens to take over—but in practice this confidence would be almost impossible to come by.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-07T08:01 (+2)

I agree that this is in some sense part of a more general utilitarianism vs intuitions thing.

Are people generally in favour of the bombings? Or do you really mean *Americans*? What do people in liberal democracies like say Spain that didn't participate in WW2 think? People in Nigeria? India? Personally, I doubt you could construct a utilitarian defense of first dropping the bombs on cities rather than starting with a warning shot demonstration at the very least. It is true, I think that war is a case where people in Western liberal democracies tend to believe that some harm to innocent civilians can be justified by the greater good. But it's also I think true that people in all cultures have a tendency to believe implausible justifications for prima facie very bad actions taken by their countries during wars.

Larks @ 2025-08-08T01:03 (+4)

Are people generally in favour of the bombings? Or do you really mean *Americans*? What do people in liberal democracies like say Spain that didn't participate in WW2 think? People in Nigeria? India? Personally, I doubt you could construct a utilitarian defense of first dropping the bombs on cities rather than starting with a warning shot demonstration at the very least.

I don't know about globally, but there are a lot of Chinese people, and they generally support the bombings, which has to take us a fair bit of the the way towards general support. (I'm not aware of any research into the views of Indians or Nigerians). And the classic utilitarian defense is that there were a limited number of bombs of unknown reliability, so they couldn't be wasted - though to be honest, asking for warning shots seems a bit like special pleading. Warning shots are for deterring aggression in the first place - not for after the attacker has already struck, and shows no sign of stopping.

Matrice Jacobine @ 2025-08-08T10:37 (+3)

The overwhelming majority of Manhattan Project scientists, as well as the Undersecretary of the Navy, believed there should be a warning shot. It makes total sense from a game theory perspective to do warning shots when you believe your military advantage has significantly increased in a way that significantly change their own calculus.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-11T07:46 (+2)

My point wasn't necessarily that I believe that most people worldwide think the bombing was wrong, but rather that it's unlikely JackM has access to what "most people" think worldwide, and that it is plausible for obvious reasons that insofar as he does have a sense of what most Americans think about this, it's at least very plausible for standard reasons of nationalism and in-group bias that Americans have a more favourable view of the bombings than the world as whole. But "plausible" just means that, not definitely true.

As for the fact that they had few bombs: that is true, and I did briefly think it might enable the utilitarian defence you are giving, but if you think things through carefully, I don't think it really works all that well. The reason that the bombings pushed Japan towards surrender* is not, primarily, that it was much harder for Japan to fight on once Hiroshima and Nagasaki were gone, but rather the fear that US could drop more bombs. In other words, the Japanese weren't prepared to risk the US having more bombs ready, or being able to manufacture them quickly. That fear could certainly also have been generated simply by proof that the US had the bomb. I guess you could try and argue a warning shot would have had less psychological impact, but that seems speculative to me.

*There is, I believe, some level of historical debate about how much longer they would have held out anyway, so I am not sure whether the bombings alone were decisive.

JackM @ 2025-08-08T11:44 (+2)

That may be fair. Although, if what you're saying is that the bombings weren't actually justified when one uses utilitarian reasoning, then the horror of the bombings can't really be an argument against utilitarianism (although I suppose it could be an argument against being an impulsive utilitarian without giving due consideration to all your options).

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-12T11:52 (+2)

I did not use the bombings as an argument against utilitarianism.

JackM @ 2025-08-12T12:05 (+2)

Yeah, I didn't meant to imply you had. This whole Hiroshima convo got us quite off topic. The original point was that Ben was concerned about digital beings outnumbering humans. I think that concern originates from some misplaced feeling that humans have some special status on account of being human.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-06T09:42 (+5)

I agree with the core point, and that was part of my motivation for working on this area. There is a counterargument, as Ben says, which is that any particular intervention to promote Flourishing might be very non-robust.

And there is an additional argument, which is that in worlds in which you have successfully reduced x-risk, the future is more likely to be negative-EV (because worlds in which you have successfully reduced x-risk are more likely to be worlds in which x-risk is high, and those worlds are more likely to be going badly in general (e.g. great power war)).

I don't think that wild animal suffering is a big consideration here, though, because I expect wild animals to be a vanishingly small fraction of the future population. Digital beings can inhabit a much wider range of environments than animals can, so even just in our own solar system in the future I'd expect there to be over a billion times as many digital beings as wild animals (the sun produces 2 billion times as much energy as lands on Earth); that ratio gets larger when looking to other star systems.

JackM @ 2025-08-05T11:17 (+4)

A counter argument to the wild animal point is that some risks may kill humanity but not all wild animals. I wonder if that’s the case for most catastrophic risks.

lilly @ 2025-08-19T21:31 (+19)

I apologize because I'm a bit late to the party, haven't read all the essays in the series yet, and haven't read all the comments here. But with those caveats, I have a basic question about the project:

Why does better futures work look so different from traditional, short-termist EA work (i.e., GHW work)?

I take it that one of the things we've been trying to do by investing in egg-sexing technology, strep A vaccines, and so on is make the future as good as possible; plenty of these projects have long time horizons, and presumably the goal of investing in them today is to ensure that—contingent on making it to 2050—chickens live better lives and people no longer die of rheumatic heart disease. But the interventions recommended in the essay on how to make the future better look quite different from the ongoing GHW work.

Is there some premise baked into better futures work that explains this discrepancy, or is this project in some way a disavowal of current GHW priorities as a mechanism for creating a better future? Thanks, and I look forward to reading the rest of the essays in the series.

JackM @ 2025-08-20T02:01 (+1)

That's a great question. Longtermists look to impact the far future (even thousands/million of years in the future) rather than the nearish future because they think the future could be very long, so there's a lot more value at stake looking far out.

They also think there are tangible, near-term decisions (e.g. about AI, space governance etc.) that could lock in values or institutions and shape civilization’s long-run trajectory in predictable ways. You can read more on this in essay 4 "Persistent Path-Dependence".

Ultimately, it just isn't clear how things like saving/improving lives now will influence the far future trajectory, so these aren't typically prioritized by longtermists.

lilly @ 2025-08-20T02:53 (+4)

Okay, so a simple gloss might be something like "better futures work is GHW for longtermists"?

In other words, I take it there's an assumption that people doing standard EA GHW work are not acting in accordance with longtermist principles. But fwiw, I get the sense that plenty of people who work on GHW are sympathetic to longtermism, and perhaps think—rightly or wrongly—that doing things like facilitating the development of meat alternatives will, in expectation, do more to promote the flourishing of sentient creatures far into the future than, say, working on space governance.

JackM @ 2025-08-20T16:44 (+2)

I think generally GHW people don’t think you can predictably influence the far future because effects “wash out” over time, or think trying to do so is fanatical (you’re betting on an extremely small chance of very large payoff).

If you look at, for example, GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness analyses, effects in the far future don’t feature. If they thought most of the value of saving a life was in the far future you would think they would incorporate that. Same goes for analyses by Animal Charity Evaluators.

Longtermists think they can find interventions that avoid the washing out objection. Essay 4 of the series goes into this, also see the shorter summary.

Seth Herd @ 2025-08-04T23:06 (+12)

Copied from my comment on LW, because it may actually be more relevant over here where not everyone is convinced about alignment being hard. It's a really sketchy presentation of what I think are strong arguments for why the consensus on this is wrong on this.

I really wish I could agree. I think we should definitely think about flourishing when it's a win/win with survival efforts. But saying we're near the ceiling on survival looks wildly too optimistic to me. This is after very deeply considering our position and the best estimate of our odds, primarily surrounding the challenge of aligning superhuman AGI (including surrounding societal complications).

There are very reasonable arguments to be made about the best estimate of alignment/AGI risk. But disaster likelihoods below 10% really just aren't viable when you look in detail. And it seems like that's what you need to argue that we're near ceiling on survival.

The core claim here is "we're going to make a new species which is far smarter than we are, and that will definitely be fine because we'll be really careful how we make it" in some combination with "oh we're definitely not making a new species any time soon, just more helpful tools".

When examined in detail, assigning a high confidence to those statements is just as silly as it looks at a glance. That is obviously a very dangerous thing and one we'll do pretty much as soon as we're able.

90% plus on survival looks like a rational view from a distance, but there are very strong arguments that it's not. This won't be a full presentation of those arguments; I haven't written it up satisfactorily yet, so here's the barest sketch.

Here's the problem: The more people think seriously about this question, the more pessimistic they are.

(edit - we asymptote at different points but almost universally far above 10% p(doom))

And those who've spent more time on this particular question should be weighted far higher. Time-on-task is the single most important factor for success in every endeavor. It's not a guarantee but it's by far the most important factor. It dwarfs raw intelligence as a predictor of success in every domain (although the two are multiplicative).

The "expert forecasters" you cite don't have nearly the time-on-task of thinking about the AGI alignment problem. Those who actually work in that area are very systematically more pessimistic the longer and more deeply we've thought about it. There's not a perfect correlation, but it's quite large.

This should be very concerning from an outside view.

This effect clearly goes both ways, but that only starts to explain the effect. Those who intuitively find AGI very dangerous are prone to go into the field. And they'll be subject to confirmation bias. But if they were wrong, a substantial subset should be shifting away from that view after they're exposed to every argument for optimism. This effect would be exaggerated by the correlation between rationalist culture and alignment thinking; valuing rationality provides resistance (but certainly not immunity!) to motivated reasoning/confirmation bias by aligning ones' motivations with updating based on arguments and evidence.

I am an optimistic person, and I deeply want AGI to be safe. I would be overjoyed for a year if I somehow updated to only 10% chance of AGI disaster. It is only my correcting for my biases that keeps me looking hard enough at pessimistic arguments to believe them based on their compelling logic.

And everyone is affected by motivated reasoning, particularly the optimists. This is complex, but after doing my level best to correct for motivations, it looks to me like the bias effects have far more leeway to work when there's less to push against. The more evidence and arguments are considered, the less bias takes hold. This is from the literature on motivated reasoning and confirmation bias, which was my primary research focus for a few years and a primary consideration for the last ten.

That would've been better as a post or a short form, and more polished. But there it is FWIW, a dashed-off version of an argument I've been mulling over for the past couple of years.

I'll still help you aim for flourishing, since having an optimistic target is a good way to motivate people to think about the future.

Edit: I realize this isn't an airtight argument and apologize for the tone of confidence in the absence of presenting the whole thing carefully and with proper references.

Arepo @ 2025-08-05T06:43 (+15)

Here's the problem: The more people think seriously about this question, the more pessimistic they are.

Citation needed on this point. I you're underrepresenting the selection bias for a start - it's extremely hard to know how many people have engaged with and rejected the doomer ideas since they have far less incentive to promote their views. And those who do often find sloppy argument and gross misuses of the data in some of the prominent doomer arguments. (I didn't have to look too deeply to realise the orthogonality thesis was a substantial source of groupthink)

Even within AI safety workers, it's far from clear to me that the relationship you assert exists. My impression of the AI safety space is that there are many orgs working on practical problems that they take very seriously without putting much credence in the human-extinction scenarios (FAR.AI, Epoch, UK AISI off the top of my head).

One guy also looked at the explicit views of AI experts and found if anything an anticorrelation between their academic success and their extinction-related concern. That was looking back over a few years and obviously a lot can change in that time, but the arguments for AI extinction had already been around for well over a decade at the time of that survey.

The "expert forecasters" you cite don't have nearly the time-on-task of thinking about the AGI alignment problem.

This is true for forecasting in every domain. There are virtually always domain experts who have spent their careers thinking about any given question, and yet superforecasters seem to systematically outperform them. If this weren't true, superforecasting wouldn't be a field - we'd just go straight to the domain experts for our predictions.

Will Aldred @ 2025-08-06T09:54 (+9)

Just want to quickly flag that you seem to have far more faith in superforecasters’ long-range predictions than do most people who have worked full-time in forecasting, such as myself.

@MichaelDickens’ ‘Is It So Much to Ask?’ is the best public writeup I’ve seen on this (specifically, on the problems with Metaculus’ and FRI XPT’s x-risk/extinction forecasts, which are cited in the main post above). I also very much agree with:

Excellent forecasters and Superforecasters™ have an imperfect fit for long-term questions

Here are some reasons why we might expect longer-term predictions to be more difficult:

- No fast feedback loops for long-term questions. You can’t get that many predict/check/improve cycles, because questions many years into the future, tautologically, take many years to resolve. There are shortcuts, like this past-casting app, but they are imperfect.

- It’s possible that short-term forecasters might acquire habits and intuitions that are good for forecasting short-term events, but bad for forecasting longer-term outcomes. For example, “things will change more slowly than you think” is a good heuristic to acquire for short-term predictions, but might be a bad heuristic for longer-term predictions, in the same sense that “people overestimate what they can do in a week, but underestimate what they can do in ten years”. This might be particularly insidious to the extent that forecasters acquire intuitions which they can see are useful, but can’t tell where they come from. In general, it seems unclear to what extent short-term forecasting skills would generalize to skill at longer-term predictions.

- “Predict no change” in particular might do well, until it doesn’t. Consider a world which has a 2% probability of seeing a worldwide pandemic, or some other large catastrophe. Then on average it will take 50 years for one to occur. But at that point, those predicting a 2% will have a poorer track record compared to those who are predicting a ~0%.

- In general, we have been in a period of comparative technological stagnation, and forecasters might be adapted to that, in the same way that e.g., startups adapted to low interest rates.

- Sub-sampling artifacts within good short-term forecasters are tricky. For example, my forecasting group Samotsvety is relatively bullish on transformative technological change from AI, whereas the Forecasting Research Institute’s pick of forecasters for their existential risk survey was more bearish.

How much weight should we give to these aggregates?

My personal tier list for how much weight I give to AI x-risk forecasts to the extent I defer:

- Individual forecasts from people who seem to generally have great judgment, and have spent a ton of time thinking about AI x-risk forecasting e.g. Cotra, Carlsmith

- Samotsvety aggregates presented here

- A superforecaster aggregate (I’m biased re: quality of Samotsvety vs. superforecasters, but I’m pretty confident based on personal experience)

- Individual forecasts from AI domain experts who seem to generally have great judgment, but haven’t spent a ton of time thinking about AI x-risk forecasting (this is the one I’m most uncertain about, could see anywhere from 2-4)

- Everything else I can think of I would give little weight to.[1][2]

Separately, I think you’re wrong about UK AISI not putting much credence on extinction scenarios? I’ve seen job adverts from AISI that talk about loss of control risk (i.e., AI takeover), and I know people working at AISI who—last I spoke to them—put ≫10% on extinction.

- ^

Why do I give little weight to Metaculus’s views on AI? Primarily because of the incentives to make very shallow forecasts on a ton of questions (e.g. probably <20% of Metaculus AI forecasters have done the equivalent work of reading the Carlsmith report), and secondarily that forecasts aren’t aggregated from a select group of high performers but instead from anyone who wants to make an account and predict on that question.

- ^

Why do I give little weight to AI expert surveys such as When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts? I think most AI experts have incoherent and poor views on this because they don’t think of it as their job to spend time thinking and forecasting about what will happen with very powerful AI, and many don’t have great judgment.

Arepo @ 2025-08-06T10:43 (+2)

You might be right re forecasting (though someone willing in general to frequently bet on 2% scenarios manifesting should fairly quickly outperform someone who frequently bets against them - if their credences are actually more accurate).

I think you’re wrong about UK AISI not putting much credence on extinction scenarios? I’ve seen job adverts from AISI talking about loss of control risk (i.e., AI takeover), and how ‘the risks from AI are not sci-fi, they are urgent.’ And I know people working at AISI who, last I spoke to them, put ≫10% on extinction.

The two jobs you mention only refer to 'loss of control' as a single concern among many - 'risks with security implications, including the potential of AI to assist with the development of chemical and biological weapons, how it can be used to carry out cyber-attacks, enable crimes such as fraud, and the possibility of loss of control.'

I'm not claiming that these orgs don't or shouldn't take the lesser risks and extreme tail risks seriously (I think they should and do), but denying the claim that people who 'think seriously' about AI risks necessarily lean towards high extinction probabilities.

elifland @ 2025-08-06T16:30 (+8)

There are virtually always domain experts who have spent their careers thinking about any given question, and yet superforecasters seem to systematically outperform them.

I don't think this has been established. See here

Seth Herd @ 2025-08-05T22:12 (+3)

I don't have a nice clean citation. I don't think one exists. I've looked at an awful lot of individual opinions and different surveys. I guess the biggest reason I'm convinced this correlation exists is that arguments for low p(doom) very rarely actually engage arguments for risk at their strong points (when they do the discussions are inconclusive in both directions - I'm not arguing that alignment is hard, but that it's very much unknown how hard it is).

There appears to be a very high correlation between misunderstanding the state of play, and optimism. And because it's a very complex state of arguments, the vast majority of the world misunderstands it pretty severely.

I very much wish it was otherwise; I am an optimist who has become steadily more pessimistic as I've made alignment my full-time focus - because the arguments against are subtle (and often poorly communicated) but strong.

They arguments for the difficulty of alignment are far too strong to be rationally dismissed down to the 1.4% or whatever it was that the superforecasters arrived at. They have very clearly missed some important points of argument.

The anticorrelation with academic success seems quite right and utterly irrelevant. As a career academic, I have been noticing for decades that academic success has some quite perverse incentives.

I agree that there are bad arguments for pessimism as well as optimism. The use of bad logic in some prominent arguments says nothing about the strength of other arguments. Arguments on both sides are far from conclusive. So you can hope arguments for the fundamental difficulty of aligning network-based AGI are wrong, but assigning a high probability they're wrong without understanding them in detail and constructing valid counterarguments is tempting but not rational.

If there's a counterargument you find convincing, please point me to it! Because while I'm arguing from the outside view, my real argument is that this is an issue that is unique in intellectual history, so it can really only be evaluated from the inside view. So that's where most of my thoughts on the matter go.

All of which isn't to say the doomers are right and we're doomed if we don't stop building network-based AGI. I'm saying we don't know. I'm arguing that assigning a high probability right now based on limited knowledge to humanity accomplishing alignment is not rationally justified.

I think that fact is reflected in the correlation of p(doom) with time-on-task only on alignment specifically. If that's wrong I'd be shocked, because it looks very strong to me, and I do work hard to correct for my own biases. But it's possible I'm wrong about this correlation. If so it will make my day and perhaps my month or year!

It is ultimately a question that needs to be resolved at the object level; we just need to take guesses about how to assign resources based on outside views.

Arepo @ 2025-08-06T04:28 (+3)

because it's a very complex state of arguments, the vast majority of the world misunderstands it pretty severely... They have very clearly missed some important points of argument.

This seems like an argument from your own authority. I've read a number of doomer arguments and personally found them unconvincing, but I'm not asking anyone to take my word for it. Of course you can always say 'you've read the wrong arguments', but in general, if your argument amounts to 'you need to read this 10s-of-thousands-of-words-argument' there's no reason for an observer to believe that you understand it better than other intelligent individuals who've read it and reject it.

Therefore this:

If there's a counterargument you find convincing, please point me to it!

... sounds like special pleading. You're trying to simultaneously claim both that a) the arguments for doom are so so complicated that no-one's anti-doom views have any weight unless they've absorbed a nebulous gestalt of pro-doomer literature and b) that the purported absence of a single gestalt-rebutting counterpoint justifies a doomer position.

And to be clear, I don't think the epistemic burden should be equalised - I think it should be the other way around. Arguments for extinction by AI are necessarily built on a foundation of a priori and partially empirical premises, such that the dissolution of any collapses the whole argument. To give a few examples, such arguments require one to believe:

- No causality of intelligence on goals, or too weak causality to outweigh other factors

- AI to develop malevolent goals despite the process of developing it inherently involving incremental steps towards making it closer to doing what its developers want

- AI to develop malevolent goals despite every developer working on it wanting it not to kill them

- Instrumental convergence

- Continued exponential progress

- Without the (higher) exponential energy demands we're currently seeing

- An ability to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances that's entirely absent from modern deep learning algorithms

- That the ceiling of AI will be sufficiently higher than that of humans to manipulate us on an individual or societal level without anyone noticing and sounding the alarm (or so good at manipulating us that even with the alarm sounding we do its bidding)

- That it gets to this level fast enough/stealthily enough that no-one shuts it down

And to specifically believe that AI extinction is the most important thing to work on requires further assumptions, like

- nothing else (including AI) is likely to do serious civilisational damage before AI wipes us out

- or that civilisational collapse is sufficiently easy to recover from that it's basically irrelevant to long term expectation

- it will be morally bad if AI replaces us

- that the thesis of the OP is false, and that survival work is either the same as or higher EV than flourishing work

- that there's anything we can actually do to prevent our destruction, assuming all the above propositions are true

Personally I weakly believe most of these propositions, but even if I weakly believed all of them, that would still leave me with extremely low total concern for Yudkowskian scenarios.

Obviously there are weaker versions of the AI thesis like 'AI could cause immense harm, perhaps by accident and perhaps by human intent, and so is an important problem to work on' which it's a lot more reasonable to believe.

But when you assert that 'The more people think seriously about this question, the more pessimistic they are', it sounds like you mean they become something like Yudkowskyesque doomers - and I think that's basically false outside certain epistemic bubbles.

Inasmuch as it's true that people who go into the field both tend to be the most pessimistic and don't tend to exit the field in large numbers after becoming insufficiently pessimistic, I'll bet you for any specific version of that claim you want to make, something extremely similar is true of biorisk, climate change, s-risks in general, and longterm animal welfare in particular. I'd bet at slightly longer odds the same is true of national defence, global health, pronatalism, antinatalism, nuclear disarmament, conservation, gerontology and many other high-stakes areas.

I think that fact is reflected in the correlation of p(doom) with time-on-task only on alignment specifically

I think most people who've put much thought into it agree that the highest probability of human extinction by the end of the century comes from misaligned AI. But that's not sufficient to justify a strong p(doom) position, let alone a 'most important cause' position. I also think it comes from a largely unargued-for (and IMO clearly false) assumption that we'd lose virtually no longterm expected value from civilisational collapse.

Ben_West🔸 @ 2025-08-05T05:04 (+9)

I think his use of "ceiling" is maybe somewhat confusing: he's not saying that survival is near 100% (in the article he uses 80% as his example, and my sense is that this is near his actual belief). I interpret him to just mean that we are notably higher on the vertical axis than the horizontal one:

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-06T09:57 (+2)

Man, was that unclear?

Sorry for sucking at basic communication, lol.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-05T08:34 (+7)

"This effect would be exaggerated by the correlation between rationalist culture and alignment thinking"

Being part of rationalist culture is a sign that someone highly values rationality, yes. But it's also a sign that the belong to a relatively small group, with a strong sense of superiority to normies, some experiments in communal living, and a view of those outside the group as often morally and intellectually corrupt ("low decouplers" "not truth-seeking" etc.) Groups like that are not usually known for dispassionately and objectively looking at the evidence on beliefs that are central to group identity, and belief that AI risk is high seems fairly central to rationalist identity to me. It certainly could be (I mean this non-sarcastically) that rationalist culture is an exception to the general rule because it places such a high value on updating on new evidence and changing your mind, but I don't think we can be confident that rationalists are more likely to evaluate information on AI risk fairly than other people of comparable intelligence. Though I agree they are certainly better informed on AI risk than Good Judgment superforecasters, and as a GJ superforecaster, my views on AI risk have trended towards those of the rationalists recently (though still far away from >50% p|doom).

I agree optimists have other biases too. Including most simply status quo bias, which is, frankly, generally not a "bias" at all for most of the things GJ people forecast, so much as a fallible but useful heuristic, but which is probably not a great idea to apply to a genuinely revolutionary new technology.

Seth Herd @ 2025-08-05T21:38 (+1)

Agreed on all counts, except that a strong value on rationality seems very likely to be an advantage in on-average reaching more-correct beliefs. Feeling good about changing one's mind instead of bad is going to lead to more belief changes, and those tend to lead toward truth.

Good points on the rationalist community being a bit insular. I don't think about that much myself because I've never been involved with the bay area rationalist community, just LessWrong.

Rohin Shah @ 2025-08-17T08:54 (+10)

Most people really don’t want to die, or to be disempowered in their lifetimes. So, for existential risk to be high, there has to be some truly major failure of rationality going on.

... What is surprising about the world having a major failure of rationality? That's the default state of affairs for anything requiring a modicum of foresight. A fairly core premise of early EA was that there is a truly major failure of rationality going on in the project of trying to improve the world.

Are you surprised that ordinary people spend more money and time on, say, their local sports team, than on anti-aging research? For most of human history, aging had a ~100% chance of killing someone (unless something else killed them first).

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-18T11:00 (+13)

I think that most of classic EA vs the rest of the world is a difference in preferences / values, rather than a difference in beliefs. Ditto for someone funding their local sports teams rather than anti-aging research. We're saying that people are failing in the project of rationally trying to improve the world by as much as possible - but few people really care much or at all about succeeding at that project. (If they cared more, GiveWell would be moving a lot more money than it is.)

In contrast, most people really really don't want to die in the next ten years, are willing to spend huge amounts of money not to do so, will almost never take actions that they know have a 5% or more chance of killing them, and so on. So, for x-risk to be high, many people (e.g. lab employees, politicians, advisors) have to catastrophically fail at pursuing their own self-interest.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-18T11:43 (+6)

"So, for x-risk to be high, many people (e.g. lab employees, politicians, advisors) have to catastrophically fail at pursuing their own self-interest."

I don't think this obviously follows.

Firstly, because the effect of not doing unsafe AI things yourself is seldom that no one else does them, it's more of a tragedy of the commons type situation right? Especially if there is one leading lab that is irrationally optimistic about safety, which doesn't seem to require that low a view of human rationality in general.

Secondly, someone like Musk might have a value system where they care a lot about personally capturing the upside of getting to personally aligned superintelligence first, and then they might do dangerous things for the same reason that a risk neutral person will take a 90% chance of instant death and a 10% chance of living to be 10 million over the status quo.

Rohin Shah @ 2025-08-18T11:26 (+2)

I think that most of classic EA vs the rest of the world is a difference in preferences / values, rather than a difference in beliefs.

I somewhat disagree but I agree this is plausible. (That was more of a side point, maybe I shouldn't have included it.)

most people really really don't want to die in the next ten years

Is your claim that they really really don't want to die in the next ten years, but they are fine dying in the next hundred years? (Else I don't see how you're dismissing the anti-aging vs sports team example.)

So, for x-risk to be high, many people (e.g. lab employees, politicians, advisors) have to catastrophically fail at pursuing their own self-interest.

Sure, I mostly agree with this (though I'd note that it can be a failure of group rationality, without being a failure of individual rationality for most individuals). I think people frequently do catastrophically fail to pursue their own self-interest when that requires foresight.

JackM @ 2025-08-20T01:35 (+4)

Is your claim that they really really don't want to die in the next ten years, but they are fine dying in the next hundred years? (Else I don't see how you're dismissing the anti-aging vs sports team example.)

Dying when you're young seems much worse than dying when you're old for various reasons:

- Quality of life is worse when you're old

- When you're old you will have done much more of what you wanted in life (e.g. have kids and grandkids)

- It's very normal/expected to die when old

Also, I'd imagine people don't want to fund anti-aging research for various (valid) reasons:

- Skepticism it is very cost-effective

- Public goods problem means under provision (everyone can benefit from the research even if you don't fund it yourself)

- From a governmental perspective living longer is actually a massive societal issue as it introduces serious fiscal challenges as you need to fund pensions etc. From an individual perspective living longer just means having to work longer to support yourself for longer. So does anyone see anti-aging as that great?

- People discount the future

Having said all this, I actually agree with you that x-risk could be fairly high due to a failure of rationality. Primarily because we've never gone extinct so people naturally think it's really unlikely, but x-risk is rising as we get more technologically powerful.

BUT, I agree with Will's core point that working towards the best possible future is almost certainly more neglected than reducing x-risk, partly because it's just so wacky. People think about good futures where we are very wealthy and have lots of time to do fun stuff, but do they think about futures where we create loads of digital minds that live maximally-flourishing lives? I doubt it.

Larks @ 2025-08-04T21:47 (+9)

Thanks for sharing!

I'm not sure if you intend to do a separate post on it, so I'll include this feedback here. You argue that:

Conditional on successfully preventing an extinction-level catastrophe, you should expect Flourishing to be (perhaps much) lower than otherwise, because a world that needs saving is more likely to be uncoordinated, poorly directed, or vulnerable in the long run

This seems quite unclear to me. In the supplement you describe one reason it might be false (uncertainty about future algorithmic efficiency). But it seems to me there is a much bigger one: competition.

In general, competition of various kinds seems like it has been one of the most positive forces for human development - competition between individuals for excellence, between scientists for innovation, between companies for cost-effectively meeting consumer wants, and between countries. Historically 'uncoordinated' competition has often had much better results than coordination! But it also drives AI risk. A world with a single leviathan seems like it would have higher chances of survival, but also lower flourishing.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-06T09:55 (+6)

In general, competition of various kinds seems like it has been one of the most positive forces for human development - competition between individuals for excellence, between scientists for innovation, between companies for cost-effectively meeting consumer wants, and between countries. Historically 'uncoordinated' competition has often had much better results than coordination!

I agree with the historical claim (with caveats below), but I think how that historical success ports over to future expected success is at best very murky.

A few comments here why:

- Taking a firm moral stance, it’s not at all obvious that the non-centralised society today really is that great. It all depends on: (i) how animals are treated (including wild animals), if we’re just looking at the here and now; (ii) how existential risk is handled, if we’re also considering the long term. (Not claiming centralised societies would have been better, but they might have been, and even small chances of changes on how e.g. animals are treated would make a big difference.)

- And there are particular reasons why liberal institutions worked that don’t apply to the post-AGI world:

- There are radically diminishing returns to any person or group having greater resources. So it makes sense to divide up resources quite generally, and means that there are enormous gains from trade.

- There are huge gains to be had from scientific and economic developments. So a society that achieves scientific and economic development basically ends up being the best society. Liberal democracy turns out to be great for that. But that won’t be a differentiator among societies in the future.

- Different people have very different aims and values, and there are huge gains to preventing conflict between different groups. But (i) future beings can be designed; (ii) I suspect that conflict can be avoided even without liberal democracy.

- I’m especially concerned that we have a lot of risk-averse intuitions that don’t port over to the case of cosmic ethics.

- For example, when thinking about whether an autocracy would be good or bad, the natural thought is: “man, that could go really badly wrong, if the wrong person is in charge.” But, if cosmic value is linear in resources, then that’s not a great argument against autocracy-outside-of-our-solar-system; some real chance of a near-best outcome is better than a guarantee of an ok future.

- And this argument gets stronger if the cosmic value of the future is the product of how well things go on many dimensions; if so, then you want success or failure on each of those dimensions to be correlated, which you get if there’s a single decision-maker.

(I feel really torn on centralisation vs decentralisation, and to be clear I strongly share the pro-liberalism pro-decentralisation prior.)

I don't intend to do a separate post on this argument, but I'd love more discussion of the it, as it is a bit of a throwaway argument in the series, but potentially Big if true.

Larks @ 2025-08-07T01:54 (+4)

Thanks for the response!

Ben_West🔸 @ 2025-08-05T22:04 (+6)

I came here to make a similar comment: a lot of my p(doom) hinges on things like "how hard is alignment" and "how likely is a software intelligence explosion," which seem to be largely orthogonal to questions of how likely we are to get flourishing. (And maybe even run contrary to it, as you point out.)

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-06T09:48 (+6)

Fair, but bear in mind that we're conditioning on your action successfully reducing x-catastrophe. So you know that you're not in the world where alignment is impossibly difficult.

Instead, you're in a world where it was possible to make a difference on p(doom) (because you in fact made the difference), but where nonetheless that p(doom) reduction hadn't happened anyway. I think that's pretty likely to be a pretty messed up world, because, in the non-messed-up-world, the p(doom) reduction already happens and your action didn't make a difference.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-05T08:24 (+3)

"Historically 'uncoordinated' competition has often had much better results than coordination!" This is so vague and abstract that it's very hard to falsify, and I'd also note that it doesn't actually rule out that there have been more cases where coordination got better results than competition. Phrasing at this level of vagueness and abstraction about something this highly politcized strikes me as ideological in the bad way.

I'd also say that I wouldn't describe the successes of free market capitalism as success of competition but not coordination. Sure, they involve competition between firms, but they also involve a huge amount of coordination (as well as competition) within firms, and partly depend on a background of stable, rule-of-law governance that also involves coordination.

Larks @ 2025-08-05T21:46 (+4)

I feel like you are reacting to my comment in isolation, rather than as a response to a specific thing Will wrote. My comment is already significantly more concrete and less abstract than Will's on the same topic.

When Will says 'uncoordinated', he clearly doesn't mean 'the OpenAI product team is not good at using Slack', he means 'competition between large groups'. Will's key point is that marginally-saved worlds will be not very good; I am saying that the features that lead to danger here cause good things elsewhere, so marginally saved worlds might be very good. One of these features is competition-between-relevant-units. The ontological question of what the unit of competition is doesn't seem particularly relevant to this - neither Will not I are disputing the importance of coordination within firms or individuals.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-08-06T09:52 (+4)

Fair point.

JackM @ 2025-08-06T01:39 (+8)

One thing I think the piece glosses over is that “surviving” is framed as surviving this century—but in longtermist terms, that’s not enough. What we really care about is existential security: a persistent, long-term reduction in existential risk. If we don’t achieve that, then we’re still on track to eventually go extinct and miss out on a huge amount of future value.

Existential security is a much harder target than just getting through the 21st century. Reframing survival in this way likely changes the calculus—we may not be at all near the "ceiling for survival" if survival means existential security.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-06T09:35 (+9)

Thanks!

A couple of comments:

1/

I'm comparing Surviving (as I define it) and Flourishing. But if long-term existential risk is high, that equally decreases the value of increasing Surviving and the value of increasing Flourishing. So how much long-term existential risk there is doesn't affect that comparison.

2/

But maybe efforts to reduce long-term existential risk are even better than work on either Surviving or Flourishing?

In the supplement, I assume (for simplicity) that we just can't affect long-term existential risk.

But I also think that, if there are ways to affect it, that'll seem more like interventions to increase Flourishing than to increase Survival. (E.g. making human decision-making wiser, more competent, and more reflective).

3/

I think that, in expectation at least, if we survive the next century then the future is very long.

The best discussion of reasons for that I know of is Carl Shulman's comment here:

"It's quite likely the extinction/existential catastrophe rate approaches zero within a few centuries if civilization survives, because:

- Riches and technology make us comprehensively immune to natural disasters.

- Cheap ubiquitous detection, barriers, and sterilization make civilization immune to biothreats

- Advanced tech makes neutral parties immune to the effects of nuclear winter.

- Local cheap production makes for small supply chains that can regrow from disruption as industry becomes more like information goods.

- Space colonization creates robustness against local disruption.

- Aligned AI blocks threats from misaligned AI (and many other things).

- Advanced technology enables stable policies (e.g. the same AI police systems enforce treaties banning WMD war for billions of years), and the world is likely to wind up in some stable situation (bouncing around until it does).

If we're more than 50% likely to get to that kind of robust state, which I think is true, and I believe Toby does as well, then the life expectancy of civilization is very long, almost as long on a log scale as with 100%.

Your argument depends on 99%+++ credence that such safe stable states won't be attained, which is doubtful for 50% credence, and quite implausible at that level. A classic paper by the climate economist Martin Weitzman shows that the average discount rate over long periods is set by the lowest plausible rate (as the possibilities of high rates drop out after a short period and you get a constant factor penalty for the probability of low discount rates, not exponential decay)."

JackM @ 2025-08-06T23:37 (+4)

Thanks for your replies!

Arepo @ 2025-08-06T10:22 (+3)

In the supplement, I assume (for simplicity) that we just can't affect long-term existential risk.

But I also think that, if there are ways to affect it, that'll seem more like interventions to increase Flourishing than to increase Survival. (E.g. making human decision-making wiser, more competent, and more reflective).

IMO the mathematical argument for spreading out to other planets and eventually stars is a far stronger a source of existential security than increasing hard-to-pin-down properties like 'wisdom'.

If different settlements' survival were independent, and if our probability per unit time of going extinct is p, then n settlements would give p^n probability of going extinct over whatever time period. You have to assume an extremely high level of dependence or of ongoing per-settlement risk for that not to approach 0 rapidly.

To give an example, typical estimates of per-year x-risk put it at about 0.2% per year.† On that assumption, to give ourselves a better than evens chance of surviving say 100,000 years, we'd need to in some sense become 1000 times wiser than we are now. I can't imagine what that could even mean - unless it simply involves extreme authoritarian control of the population.

Compare to an admittedly hypernaive model in which we assume some interdependence of offworld settlements, such that having N settlements reduces our risk per-year risk of going to extinct by 1/sqr(N). Now for N >= 4, we have a greater than 50% chance of surviving 100,000 years - and for N = 5, it's already more than 91% likely that we survive for that long. This is somewhat optimistic in assuming that if any smaller number are destroyed they're immediately rebuilt, but extremely pessimistic given assumption of a world with N >=2, in which we somehow settle 1-3 other colonies and then entirely stop.

† (1-[0.19 probability of extinction given by end of century])**(1/[92 years of century left at time of predictions]) = 0.9977 probability of survival per year

This isn't necessarily to argue against reducing flourishing being a better option - just that te above is an example of a robust long-term-x-risk-affecting strategy that doesn't seem much like increasing flourishing.

MichaelDickens @ 2025-08-06T15:17 (+3)

I think a common assumption is that if you can survive superintelligent AI, then the AI can figure out how to provide existential safety. So all you need to do is survive AI.

("Surviving AI" means not just aligning AI, but also ensuring fair governance—making sure AI doesn't enable a permanent dictatorship or whatever.)

(FWIW I think this assumption is probably correct.)

Charlie_Guthmann @ 2025-08-04T20:20 (+5)

relevant semi- related readings

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/wmqLbtMMraAv5Gyqn

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/W4vuHbj7Enzdg5g8y/two-tools-for-rethinking-existential-risk-2

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zuQeTaqrjveSiSMYo/a-proposed-hierarchy-of-longtermist-concepts

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/fi3Abht55xHGQ4Pha/longtermist-especially-x-risk-terminology-has-biasing

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/wqmY98m3yNs6TiKeL/parfit-singer-aliens

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zLi3MbMCTtCv9ttyz/formalizing-extinction-risk-reduction-vs-longtermism

Alex Long @ 2025-08-04T19:17 (+5)

I'm not sure how this factors into the math but I also just feel like there's an argument to be made that a vision of flourishing is more inspiring and feels more worth fighting for, which would in turn become a big factor in how hard we actually fight for it (and in the process, how hard we fight for survival), which would in term increase the probability of both flourishing and survival happening. I.e. focusing on flourishing would actually make survival more likely. Like the old saying goes, "without a vision, people perish".

JackM @ 2025-08-06T01:31 (+4)

Conditional on successfully preventing an extinction-level catastrophe, you should expect Flourishing to be (perhaps much) lower than otherwise, because a world that needs saving is more likely to be uncoordinated, poorly directed, or vulnerable in the long run

It isn't enough to prevent a catastrophe to ensure survival. You need to permanently reduce x-risk to very low levels aka "existential security". So the question isn't how likely flourishing is after preventing a catastrophe, it's how likely flourishing is after achieving existential security.

It seems to me flourishing is more likely after achieving existential security than it is after preventing an extinction-level catastrophe. Existential security should require a significant level of coordination, implying a world where we really got our shit together.

Of course there are counter-examples to that. We could achieve existential security through some 1984-type authoritarian system of mass surveillance, which could be a pretty bad world to live in.

So maybe the takeaway is the approach to achieving existential security matters. We should aim for safety but in a way that leaves things open. Much like the viatopia outcome Will MacAskill outlines.

Denkenberger🔸 @ 2025-08-07T06:46 (+2)

I agree that flourishing is very important. I have thought since around 2018 that the largest advantage for the long-term future of resilience to global catastrophes is not preventing extinction, but instead increasing flourishing, such as reducing the chance of other existential catastrophes like global totalitarianism, or making it more likely that better values end up in AI.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-07T15:25 (+2)

I agree re preventing catastrophes at least - e.g. a nuclear war has great long-term harm via destroying many leading democracies, making the post-catastrophe world less democratic, even if it doesn't result in extinction.

On resilience in particular, I'd need to see the argument spelled out a bit more.

OscarD🔸 @ 2025-08-08T11:41 (+2)

Why would the post-catastrophe world be less democratic?

William_MacAskill @ 2025-08-08T16:15 (+2)

Because the democracies (N America, Europe) would have been differentially destroyed (or damaged), and I think that the world is "unusually" democratic (i.e. more than the average we'd get with many historical replays).

Denkenberger🔸 @ 2025-08-07T22:44 (+2)

If there is nuclear war without nuclear winter, there would be a dramatic loss of industrial capability which would cascade through the global system. However, being prepared to scale up alternatives such as wood gas powered vehicles producing electricity would significantly speed recovery time and reduce mortality. I think if there is less people killing each other over scarce resources, values would be better, so global totalitarianism would be less likely and bad values locked into AI would be less likely. Similarly, if there is nuclear winter, I think the default is countries banning trade and fighting over limited food. But if countries realized they could feed everyone if they cooperated, I think cooperation is more likely and that would result in better values for the future.

For a pandemic, I think being ready to scale up disease transmission interventions very quickly, including UV, in room air filtration, ventilation, glycol, and temporary working housing would make the outcome of the pandemic far better. Even if those don't work and there is a collapse of electricity/industry due to the pandemic, again being able to do backup ways of meeting basic needs like heating, food, and water[1] would likely result in better values for the future.

Then there is the factor that resilience makes collapse of civilization less likely. There's a lot of uncertainty of whether values would be better or worse the second time around, but I think values are pretty good now compared to what we could have, so it seems like not losing civilization would be a net benefit for the long-term (and obviously a net benefit for the short term).

- ^

Paper about to be submitted.

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-04T18:15 (+2)

Executive summary: In this introductory post for the Better Futures essay series, William MacAskill argues that future-oriented altruists should prioritize humanity’s potential to flourish—not just survive—since we are likely closer to securing survival than to achieving a truly valuable future, and the moral stakes of flourishing may be significantly greater.

Key points:

- Two-factor model: The expected value of the future is the product of our probability of Surviving and the value of the future conditional on survival.

- We’re closer to securing survival than flourishing: While extinction risk this century is estimated at 1–16%, the value we might achieve conditional on survival is likely only a small fraction of what’s possible.

- Moral stakes favor flourishing: If we survive but achieve only 10% of the best feasible future's value, the loss from non-flourishing could be 36 times greater than from extinction risk.

- Neglectedness of flourishing: The latent human drive to survive receives far more societal and philanthropic attention than efforts to ensure long-term moral progress or meaningful flourishing

- Tractability is a crux: While flourishing-focused work is less clearly tractable than survival-focused work, MacAskill believes this could change with sustained effort—much like AI safety and biosecurity did over the past decade.

- Caution about utopianism: The series avoids prescribing a single ideal future and instead supports developing “viatopia”—a flexible, open-ended state from which humanity can continue making moral progress.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Jonas Søvik 🔹 @ 2026-01-08T12:30 (+1)

- You might be interested in the term "thrutopia", which tries to achieve a similar thing and is gaining traction in semi-adjacent circles

On flourishing v. surviving:

I heard this story from Joe Hudson about a tennis player doing practice. She could hit the basket smth like 6/10 times. One day her coach put a coin instead and told her to hit the coin. She never hit the coin, but she would have hit the basket 9/10 times.

Where we aim can matter a lot for the outcomes we get, even without reaching "the goal" (same as it matters what questions you ask).

Joe's point is also about what we get from 'looking through'. He's an exec coach in Silicon Valley and has done venture capital, and he says something similar about the people that manage to build billion$ companies.

It's always about something more, not just making money or being big. (fx being the best, solving a problem, making a name for yourself, etc.)

Beyond Singularity @ 2025-08-06T13:28 (+1)

I agree that we should shift our focus from pure survival to prosperity. But I disagree with the dichotomy that the author seems to be proposing. Survival and prosperity are not mutually exclusive, because long-term prosperity is impossible with a high risk of extinction.

Perhaps a more productive formulation would be the following: “When choosing between two strategies, both of which increase the chances of survival, we should give priority to the one that may increase them slightly less, but at the same time provides a huge leap in the potential for prosperity.”

However, I believe that the strongest scenarios are those that eliminate the need for such a compromise altogether. These are options that simultaneously increase survival and ensure prosperity, creating a synergistic effect. It is precisely the search for such scenarios that we should focus on.

In fact, I am working on developing one such idea. It is a model of society that simultaneously reduces the risks associated with AI and destructive competition and provides meaning in a world of post-labor abundance, while remaining open and inclusive. This is precisely in the spirit of the “viatopias” that the author talks about.

If this idea of the synergy of survival and prosperity resonates with you, I would be happy to discuss it further.

Maxime Riché 🔸 @ 2025-08-06T12:06 (+1)

It is stated that, conditional on extinction, we create around zero value. Conditional on using CDT to compute our marginal impact, this is true. But conditional on EDT, this is incorrect.

Conditional on EDT:

- 84+% of the resources we would not grab, in case Earth does not create a space-faring civilization (i.e., "extinction"), would still be recovered by other space-faring civilizations. Such that working on reducing extinction has a scale 84+% lower than when assuming CDT. (ref)

- Even if we go extinct, working on flourishing or extinction still creates an astronomical amount of value/disvalue through the evidential observation we get about other civilizations (i.e., "correlations"), if you think that correlations with (non-exact-copies) dominate our evidential impact.

I guess this would add lots of complexity without changing much the conclusions, though.

Beyond Singularity @ 2025-08-05T23:51 (+1)

Really enjoyed this post! It made me realize something important: if we’re serious about creating good long-term futures, maybe we should actively search for scenarios that do more than just help humanity survive. Scenarios that actually make life deeply meaningful.

Recently, an idea popped into my head that I keep coming back to. At first, I dismissed it as a bit naive or unrealistic, but the more I think about it, the more I feel it genuinely might work. It seems to solve several serious problems at once. For example destructive competition, the loss of meaning in life in a highly automated future, and the erosion of community. Every time I return to this idea, I am amazed at how naturally it all fits together.

I'm really curious now. Has anyone else here had that kind of experience—where an idea that initially seemed strange turned out to feel surprisingly robust? And from your perspective, what are the absolute "must-have" features any serious vision of the future should include?

dirtcheap @ 2025-08-05T13:47 (+1)

The question in the title is good food for thought, and I'm not sure if one should aim for survival or flourishing from a reasoned point of view. If making the decision based on intuition, I'd choose flourishing, just because it's what excites me about the future.

Currently I'm not convinced that a near-best future is hard to achieve, after reading (some of) part 2 of 6 from the Forethought website. One view is that the value of the future should be judged by those in the future, and that as long as the world is changing we don't know the value of it yet [1]. So this future we're talking about could take a long time to arrive, when things become stable in the cosmic scale. Then, in this world of technological maturity and a stable reference class of moral patients, we ask if they find that the world is near-best (a eutopia).

Under this rubric a eutopia seems more likely because the close ancestors of the people of the future will have navigated to it. Although oppression and other ways of non-flourishing aren't ruled out, the assumption of a stable equilibrium rules out war and active conflict.