Party Politics for Animal Advocacy: Part 1: Animal-focused minor political parties

By Animal Ask, Ren Ryba @ 2023-10-06T05:57 (+132)

Key Points

- Animal parties are minor (niche) political parties with a single-issue focus on animals.

- Animal parties can win seats in elections that use proportional representation. The most important strategic decision is to choose to contest elections where seats can be won with just a couple of percent of the vote. Animal parties have won seats in five countries (Australia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Portugal).

- When an animal party wins even one seat or a couple of seats, the impact for animals is typically positive and moderate. Occasionally, the impact can be enormous.

- We recommend a handful of countries where we think small grants are likely to help animal parties win at least one seat. Providing initial funding for animal parties in these countries appears to be low-hanging fruit, and this small level of funding is likely to have a disproportionately high level of impact.

Executive Summary

This approach involves establishing political parties with an explicit, and typically single-issue, focus on animal advocacy. These parties are minor (niche) parties. Animal parties can usually only win seats in elections that use proportional representation.

There are a few ways that animal parties can influence the lives of animals. The main way is by winning seats in legislatures and exercising power over legislation, government budgets, and so on. Animal parties can also influence policy in ways that do not necessarily require winning elections, such as obtaining policy concessions from other parties and setting the political agenda.

Currently, animal parties have won seats in national and sub-national legislatures in five countries (Australia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Portugal). The track record of the animal parties in these countries shows that the impact is positive and moderate, though massive wins do happen sometimes. The impact falls into four main categories:

- Large policy wins, which seem rare but enormous (i.e., hits-based). These crop up on the rare occasions when the policy agenda and the specific makeup of the legislature provide a window for an animal party to secure large policy concessions from other parties. Examples include major policy changes (e.g. inclusion of fish in animal welfare laws or bans on widespread farming practices like beak trimming) or allocating millions of dollars for animal welfare in national budgets.

- Small policy wins, which seem quite common. Examples include policies that benefit small numbers of animals (e.g. bans on particular types of hunting, restrictions on animal experimentation).

- Shifting the political agenda and influencing the policies of other parties. This effect is notoriously difficult to measure, though it does seem to be positive and meaningful.

- Capitalising on the non-legislative benefits of being an MP. This can include joining parliamentary committees, using the public stature of an MP to gain media attention for animal issues, and using allocated budgets to conduct campaigns outside of parliament.

In elections, animal parties typically attract just a few percent of the vote (e.g. 0 - 3%). There are numerous jurisdictions around the world where parties can win seats with modest votes like this. We believe that these jurisdictions are low-hanging fruit. Forming parties and contesting elections in these jurisdictions would result in animals gaining representation in a number of additional legislatures. There is less evidence that animal parties can readily expand their vote through advertising - instead, it appears that animal parties are mainly supported by a small core of passionate voters, and that the vote will therefore remain somewhat steady at around 0 - 3% over time. So, we think that the most important consideration is not necessarily advertising or crafting a perfect campaign strategy, but rather picking the right elections to contest, i.e. running in elections where parties can win seats with just a couple of percent of the vote.

We ask whether there are any legislatures around the world where a) animal parties are not currently contesting elections, and b) an animal party would probably win at least one seat if such a party were formed and contested an election. In some of these jurisdictions, an animal party does exist but it is not contesting all available elections.

We think that the most promising jurisdictions, along with the number of seats we would expect to win, are as follows:

- Switzerland (Swiss Animal Party / Tierpartei Schweiz): ~8-9 seats (across regional + national legislatures)

- Brazil (Animal Party of Brazil / Partido Animalista): ~2-5 seats (across regional + national legislatures)

- South Africa (new party): ~4 seats (across regional + national legislatures)

- Chile (Animal Party of Chile / Partido Animalista de Chile): ~1 seat (national legislature)

- Israel (Justice for All Party): ~1 seat (national legislature)

- Argentina (new party): ~1 seat (national legislature)

We also identified a few jurisdictions where the expected number of seats is more modest. Nevertheless, we think that these jurisdictions are still worth considering:

- Norway (new party): ~0-1 seats (national legislature)

- Albania (new party): ~0-1 seats (national legislature)

- Colombia (new party): ~0-1 seats (national legislature)

- Sri Lanka (new party): ~0-1 seats (national legislature)

- Dominican Republic (new party): ~0-1 seats (national legislature)

We would also recommend for all existing animal parties to ensure that they contest all elections available to them, including elections for state or regional parliaments.

The next step would be to reach out to local animal advocacy communities (or animal parties, where applicable) in the countries listed above. We have not considered the local contexts of these countries when forecasting the expected number of seats, so our forecasts may need to be adjusted up or down based on local considerations. For Switzerland, Brazil, Chile, and Israel, it would also be important to check whether the existing animal parties are indeed limited by funding.

We emphasise that all animal parties are great and should be supported, but these are the countries where an initial seed grant from a foundation is likely to generate a disproportionately high impact.

The costs to funders would be relatively small. These new parties may need financial support to contest the first election in each country. Most of this cost would pay for advertising, an online presence, and enabling a small team to work full-time on an election campaign in the few weeks immediately before the election. We suspect that around ~$30,000 USD would be the upper limit on how much a party would need for the first election. After the first election, the party would usually not require ongoing support from foundations - any elected legislators would receive a salary, the party may be eligible for government funding, and the party may build a base of paying members.

We also conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis to illustrate the impacts that animal parties can have. Basically, the lessons from this analysis are that: costs are low; most elected animal parties can successfully pass small policies (benefiting thousands of wild or companion animals); and some elected animal parties can successfully pass enormous policies (benefiting millions of farmed animals). This approach is difficult to scale as it is limited by the availability of legislatures where seats can be won with just a few percent of the vote. However, given the low costs, the positive impact, and the opportunity for occasional big wins, we think that helping animal parties contest additional elections would be a great part of the movement's portfolio.

1. How Do Animal Advocacy Parties Work?

This approach involves establishing political parties with an explicit, and typically single-issue, focus on animal advocacy. These parties are almost always minor parties (the only exceptions being when parties join larger alliances, as in France).

Animal parties can realise impact by pursuing three main strategies. Of course, these strategies can support each other, and each strategy benefits from obtaining votes.

- Winning seats. A few parties have won seats at the national or regional/state levels (see table below). There have also been some successes at the supranational level (European Union) and the local level. When an animal party wins seats, it can influence legislation, which can be a major opportunity for policy influence. It is typically unrealistic for minor parties to implement their own legislation. Parliamentarians can also use their status to gain attention for issues, such as in the media or by building coalitions with other parliamentarians from other parties (1).

- Policy concessions. For example, we illustrated in a previous article how the animal party in Australia can secure pro-animal policies from the government simply by running in elections (2). The election summarised in that article used preferential voting, in which a voter casts their vote by ranking the available candidates. This allowed the animal party to obtain policy concessions from one of the two major parties in exchange for having the animal party's voters rank that party above the competing major party when voting.

- Agenda-setting. For example, the animal party in the Netherlands "did not seek to implement its own animal welfare proposals directly, but rather it sought to make established parties work harder on animal issues through their participation in elections and in parliament" (3). Influencing the agenda may be easiest for parties that can win seats, though parties can achieve some influence over the agenda simply by being very active during elections (2).

Animal parties are unlikely to represent a pathway to victory for the animal advocacy movement on their own. The reason is that the success of animal parties is usually tied to public opinion. Nevertheless, animal parties can have an impact well beyond their level of formal electoral success, so animal parties could form one part of a portfolio of strategies used by the movement.

2. Theory of Change

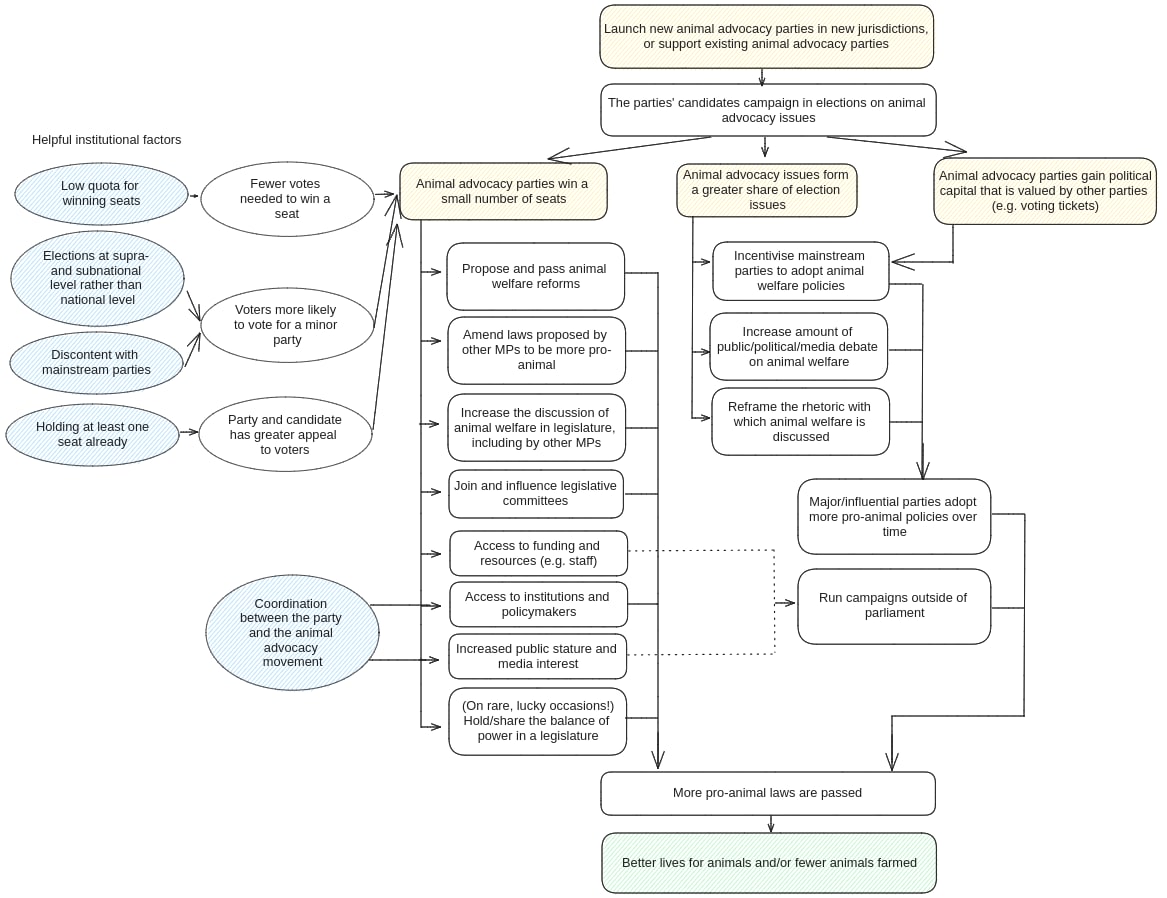

The following diagram summarises the mechanisms by which animal parties contesting legislative elections can help animals. The main mechanism is, of course, winning one seat or a handful of seats and then using that position inside the legislature to pass animal welfare laws and to secure pro-animal concessions in other legislator's proposed laws. However, as the diagram shows, this is one mechanism among many. Many of these mechanisms are discussed in detail later in the report (see sections "8. Track Record of Existing Parties" and "10. Academic Literature").

Legend:

- Yellow bubbles = central points in the theory of change

- Blue bubbles = helpful institutional factors that are out of the movement's control but useful to look out for

- Green bubbles = end goal

Since our analysis is focused on winning just one seat or a handful of seats in a legislature, this raises the question of how much policy influence a party can exert in a large legislature by holding just a handful of seats. On this topic, one cannot generalise - the answer will vary wildly across jurisdictions, and even in the same jurisdiction across terms of parliament.

On one extreme, there are cases where a single seat gives a minor party the power to make or break governments. We can illustrate using an example from outside animal politics. The Australian 2010 federal election resulted in two MPs striking the jackpot - the election resulted in a hung parliament, where the balance of power during the formation of government was ultimately held by just two independent MPs. These MPs found themselves in a position where they were being courted by the two major parties (which were hoping to form government) with major policy initiatives, high-value development projects in the MPs' districts, and even an offer of a Ministerial position (4,5). If an animal party MP found themselves in this position, the policy impact for animals could be transformative. On the other extreme, there are cases where a government commands a majority of seats, meaning that a single seat held by a minor party would be of little relevance.

Most of the time, minor parties that win a seat in a legislature would find themselves somewhere in between those extremes. Furthermore, whether an elected animal party finds itself in a powerful legislative position or not, merely holding membership in a legislature can also allow a party to exert policy influence through other means. One such means is sitting on parliamentary committees. For example, a Member of Parliament from the Animal Justice Party in New South Wales, Australia was the chair of the Select Committee on Animal Cruelty Laws (and a member of many other committees). Another way to exert policy influence is by capitalising on the public stature, staff budgets, and travel rights that come with being an MP. People elected to legislatures can use the profile and resources associated with this position to draw attention to their issues. This was exploited by one early legislator from the Australian Greens, who "for most of her time in parliament concentrated on the outside world", attracting substantial media attention to her chosen issues (1). It is easy to see how a legislator from an animal party could substantially magnify the attention given to, say, undercover investigations on factory farms.

3. Voting Systems and Minor Parties

In this report, we are mainly interested in how parties influence policy by winning seats in legislatures or otherwise influencing legislative elections). Our current view is that animal parties can successfully win seats in proportional systems, but this would be extremely difficult in majoritarian systems. Animal parties can certainly have meaningful policy influence without winning seats, but they would need to explore other avenues for achieving impact.

3.1 We focus on proportional representation

We distinguish between two broad classes of election systems.

- Majoritarian systems. These are also called "winner-takes-all" systems because the most popular major parties (typically two major parties) win almost all of the available seats. The percentage of seats won by the major parties typically exceeds their combined percentage of the vote. An example of a majoritarian system is First-Past-the-Post as used in the United States Congress. Importantly, we consider some preferential voting systems to be majoritarian, an example of which is the Instant-Runoff Vote used for the lower house in the Australian Parliament.

- Proportional systems. These systems distribute seats to parties roughly in proportion to the share of the votes that the parties received - a party receiving 10% of the vote can expect to receive about 10% of the available seats. There are a few different mathematical formulae used to distribute the seats. Some jurisdictions have a minimum threshold that parties must surpass before receiving any seats (e.g. 5% of the vote).

There is also a third type of electoral system - the ni-ni system. This is just a category that captures all miscellaneous systems that aren't accurately described as majoritarian or proportional. This term is an abbreviation of the French phrase "ni l'un ni l'autre", meaning "neither one nor the other" (6). We do note that, for the purposes of this report, we treat some ni-ni systems as proportional systems (e.g. mixed electoral systems in which voters "cast separate votes for two sets of seats allocated by different systems, most commonly single-member plurality and proportional representation"; and proportional with majoritarian incentives, in which "other electoral rules give incentives to support larger parties" (6)).

Animal parties are minor parties. How does the election system influence the success or failure of minor parties?

When it comes to majoritarian systems, the conventional wisdom is captured by Duverger's law. This law states that majoritarian systems naturally lead to stable, two-party systems in which minor parties are doomed to exclusion from the legislature (7). The mechanism typically offered to explain this pattern is that a voter does not want to "waste" their vote by voting for a party that is unlikely to win a seat in that voter's electorate - this leads to voters almost always voting for one or two major parties, which in turn makes minor parties seem like even less viable options (8). In contrast, Duverger concluded that proportional systems naturally lead to multi-party systems, in which minor parties often win seats (7).

While Duverger's law does hold in many jurisdictions, there are also exceptions. Voters do not always vote in the purely strategic way that is suggested above - evidence from elections shows that voters, even in majoritarian systems, simply vote for the candidate they like the best (8,9).

Academic research has identified some important circumstances in which minor parties can successfully win seats in majoritarian systems:

- Regionalist parties. Historically, minor parties in majoritarian systems have been most successful when they focus on issues specific to one region, ethnicity or demographic, enabling a minor party to receive high support in a small locality (6,9,10). This effect is magnified in federalist countries: the existence of provincial legislatures "provides a power base for minor parties that can then be used as a platform for national office" (11).

- Anti-establishment parties. When voters feel discontent with established parties and frustration at the lack of options, they often express this dissatisfaction by voting for particularly radical minor parties. However, for minor parties to pursue this strategy, they must have policies sufficiently radical that they cannot be co-opted by major parties (e.g. extreme right-wing populism). This means that minor parties may have success where they can a) establish an ideology that is sufficiently distinct and radical to avoid being co-opted, and b) run on an anti-establishment platform to capture dissent in the population (8).

- Centrist parties. Centrist parties can act as a reasonable alternative to the major parties when voters are dissatisfied with the major parties. In particular, Quinn (10) shows that minor, centrist parties are most successful in electoral districts where one major party is highly dominant and the other major party is weak - this enables the minor party to appear as viable as a major party and therefore benefit from tactical and protest voting in those districts. This dynamic is specific to centrist parties.

More generally, Gerring also found that minor parties in majoritarian systems perform better when voters tend not to identify strongly with mainstream parties, and worse when mainstream parties are strongly organised (11).

With this understanding in mind, we believe that animal parties (which are minor parties by definition) will typically perform poorly in majoritarian systems:

- Animal parties are not regional. While certain demographics tend to be more supportive of animal welfare than others (12,13), the baseline support for animal parties is small (typically a few percent of the vote), so any correlation between demographics and support for animal welfare is not strong enough to concentrate potential supporters of an animal party into a specific electoral district.

- Animal parties are not really radical. While animal parties often propose some radical policy measures (e.g. the abolition of animal agriculture), animal welfare is not radical as a general topic. This means that major parties, if they feel threatened by an animal party, can safely adopt pro-animal welfare policies and therefore co-opt animal welfare as an issue (2). This means that animal parties cannot cultivate an identity that is truly and stably distinct from major parties (8). We will return to this point, as pressuring major parties into adopting pro-animal welfare policies often represents a major win in its own right. (Related to this point is the fact that radical minor parties can have animal welfare as one policy among many (14), though these parties are not really animal parties.)

- Animal parties are not really centrist. Animal parties are typically associated with left-wing and/or green politics. Notably, some animal parties are not left-wing but are single-issue (15) or even right-wing (e.g. Italy's Animalist Movement, which is not to be confused with Italy's Animalist Party). Animal welfare does attract the support of right-wing parties in some countries (e.g. the UK). In any case, it would be rare for an animal party to be positioned as the most viable centrist party for which dissatisfied voters can submit a protest vote, as required by Quinn's model (10) of centrist parties.

Based on this reasoning, our current view is that animal parties can win seats in legislatures that are elected by proportional voting systems, and we think that animal parties will find it extremely difficult to win seats in legislatures elected by majoritarian systems. However, animal parties can definitely still influence policy in majoritarian systems - it is just a matter of influencing policy by means other than winning seats. This represents the working hypothesis on which we will structure our analysis in this report, and we would welcome any counter-arguments.

3.2 Contesting more elections seems better than spending more on advertising

In this report, we adopt the following mindset: we think it is important for animal parties to contest as many (winnable) elections as possible and to support those campaigns with sufficient resources to get the party name on the ballot, to produce an attractive policy platform, and to maintain an online presence. But we are less keen on spending large amounts on advertising for animal parties during election campaigns, once the party has those minimum sufficient resources. This is a working hypothesis, subject to future evidence.

Tentatively, we believe that advertising for an animal party during an election campaign has a negligible effect on the number of seats won by the party. The alternative view is that advertising is important, and that spending more money on advertising during a campaign would allow animal parties to win more seats.

In favour of the belief that advertising is important:

- It is widely believed that political advertising by mainstream parties has a meaningful effect on their vote. This belief has empirical support in some (but not all) academic studies (16–18) and in the observation that mainstream parties almost always spend lots of money on advertising during election campaigns (though that latter observation does not necessarily prove that such spending is an effective use of money) (19). On the other hand, there has been no analysis specific to animal parties, and relatively few analyses specific to minor parties.

- The Party for the Animals in the Netherlands has witnessed a vote that is steadily increasing over time. This suggests that animal parties can increase their vote by building their popularity and profile, and advertising may be one component of this. On the other hand, there is an alternative explanation. Dinas et al (20) show that when small parties enter a legislature, they typically experience a subsequent increase in their vote because having an elected parliamentarian "signals organisational capacity and candidates’ appeal, and reduces uncertainty about parties’ ideological profile". So, the increasing profile of the Netherlands may not necessarily be related to any actual marketing.

- In Australia, the Animal Justice Party observes higher votes at election booths where party volunteers hand out flyers to voters as they arrive (2). On the other hand, this may be correlation rather than causation - perhaps naturally higher support in a particular suburb means that there are more people willing to volunteer for the party. Also, it is unclear whether volunteers handing out flyers on election day would have the same effect as paid advertising (e.g. on social media during the election campaign).

In favour of the belief that advertising is not important (i.e. our assumption for this report):

- There is reason to suspect that animal parties operate differently to mainstream parties (and even differently to other types of minor parties) and are hence an exception to conventional wisdom. One view that is common in the academic literature is that minor parties tend to attract a core of voters who are committed for ideological reasons. For example, Adams et al (21) conclude that minor parties can maximise their votes if they "maintain their policy appeal to those core voters who are drawn to them for ideological reasons". For animal parties, this would be a small core of voters who are already strongly committed to animal rights or welfare. Securing votes from other groups of people may be less tractable. Under this view, it is far more important whether the animal party has policies that appeal to this core of voters - in this case, the party simply being on the ballot may be all the advertising that is needed to win the support of this committed core. Whether the voter sees an advertisement for the animal party may therefore be less relevant.

- Votes for existing animal parties are mostly capped within a narrow range (see data in "5. Expanding Existing Parties"). It is common for animal parties contesting proportionally-represented elections to receive votes between 0% and 4%, but anything above this is quite rare. This suggests that, at the most, advertising can help within this narrow range, but perhaps not above it.

- The academic literature has found that, in general, advertising "tend[s] to produce small average effects" (19). Even if the effect of advertising is above zero, it may be small.

- In one election in Australia, the animal party invested a high marketing spend, but received a much lower vote than expected (2). On the other hand, this is a single data point, and it is impossible to tell if the vote would have been even lower without the advertising.

We emphasise that the evidence for either of these beliefs is ambiguous. There is simply no data on the effects of political advertising on the vote secured by animal parties. There are a few weak pieces of evidence on both sides of this question. This is why we are sceptical about spending the movement's resources on advertising for animal parties until stronger evidence arises - we are far more confident in spending resources to ensure that animal parties are contesting all (winnable) elections.

4. Current Seats: Where Have Animal Parties Won Seats?

The following table shows the five countries where animal parties have won elected representation at the national or regional/state level. Note that we give a more detailed description of each party's track record below (see section 8, "Track Record of Existing Parties"). This table also excludes parties that have won seats in the European Parliament rather than national or regional/state legislatures (see section 7, "European Parliament").

Table 1: Countries where animal parties have won seats at the national or regional/state level.

Country | Party | Legislature | Electoral System | Years When Seats Won | Lowest Successful Primary Vote* (see note below) |

Australia | Animal Justice Party | State upper house (New South Wales Legislative Council) in bicameral legislature | Proportional representation | 2015, 2019 | 1.8% |

State upper house (Victoria Legislative Council) in bicameral legislature | Proportional representation with group voting ticket | 2018, 2022 | 1.45% | ||

Belgium | DierAnimal (the MP has since become an independent) | Regional unicameral legislature (Brussels Regional Parliament) | Proportional representation | 2019 | 1.32% |

France** | Ecological Revolution for the Living (Révolution écologique pour le vivant) | National lower house (National Assembly) in bicameral legislature | Two-round runoff | 2022 | 45.05% (first round), 51.65% (second round)

as part of the alliance Nouvelle Union populaire écologique et sociale |

The Netherlands | Party for the Animals (Partij voor de Dieren) | National lower house (House of Representatives) in bicameral legislature | Proportional representation | 2006, 2010, 2012, 2017, 2021 | 1.3% |

National upper house (Senate) in bicameral legislature | Indirect (elected by members of provincial legislatures) | 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019 | 1.06% | ||

Provincial unicameral legislatures (multiple) | Proportional representation | 2007, 2011, 2013, 2015, 2019 | 1.88% | ||

Portugal | People-Animals-Nature (Pessoas-Animais-Natureza) | National unicameral legislature | Proportional representation | 2015, 2019, 2022 | 1.4% |

Regional unicameral legislature (Legislative Assembly of Madeira) | Proportional representation | 2011 | 2.13% | ||

Regional unicameral legislature (Legislative Assembly of the Azores) | Proportional representation | 2020 | 1.9% |

*"Lowest Successful Primary Vote" means the lowest vote in a particular electorate that successfully resulted in winning at least one seat in that electorate. This is not intended to show how popular each party is - rather, this shows how low a party's vote can be while still winning electoral representation.

**The party in France secured these extremely high votes as part of a larger alliance, due to France's system of running as political alliances. In all other contexts, it is unrealistic for an animal party to achieve a vote this high.

Note: The Italian Animalist Party did technically win a seat in the 2020 regional election in Campania, though this was a combined nomination with an environmentalist party, so we do not consider this to be a seat held by an animal party.

There are a couple of key takeaways from this table. Typically, seats have been won in legislatures that use proportional representation. The main exception is France, where the animal party joined a large and well-recognised alliance of parties. In Victoria in Australia, the election system involves a group voting ticket, an uncommon and unpredictable form of voting that can disproportionately benefit minor parties.

Also, animal parties have often won seats with just 1 - 2% of the primary vote. A vote of this level can be obtained very reliably by animal parties in most places.

Therefore, perhaps the most important strategic decision is to pick the right country and legislature in which to contest an election. In Australia, New South Wales and Victoria are the two states with the largest populations, which means that they have the largest state legislatures, which means that they have the lowest vote required to win at least one seat in a state legislature (at least in the proportionally-represented upper houses). Therefore, Australia's animal party has won seats in these legislatures, even though the party receives a very similar vote in other states.

Beyond representation within countries, some parties have won representation in a supranational legislature: the European Parliament. Members are elected using proportional representation. The parties from Germany (Human Environment Animal Welfare Party), the Netherlands (Party for the Animals), and Portugal (Peoples-Animals-Nature) have won representation in this body. We discuss the European Parliament in greater detail below (see section 7, "European Parliament").

A number of parties, including the ones listed above, have won representation at the local level (e.g. municipalities or local councils). These positions can lead to meaningful policy change for animals at the local level. However, we don't detail these victories here, as the list is long.

5. Expanding Existing Parties: Where Could Animal Parties Win More Seats?

5.1 Where do animal parties exist?

At least focusing on the strategy of actually winning seats, the best way for the animal advocacy movement to proceed could be to find jurisdictions that a) use proportional representation, b) have large enough legislatures that parties can be elected with just a few percent of the vote, and c) do not already have an existing animal party, or have an animal party that could run in additional legislatures if given extra funding.

Given the huge number of legislatures worldwide, there is still some low-hanging fruit - this is compounded by the fact that many countries have subnational legislatures at the regional/state levels, and it is common for these subnational legislatures to have power over agricultural policy anyway. Therefore, funding just a few small parties in a handful of countries could increase the power of the animal advocacy movement in legislatures worldwide.

The following countries have animal parties that have not yet won elected representation in national or regional/state legislatures: Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Moldova, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uruguay, the UK, and Turkey (2,22–24). The US has an animal party, but no proportionally-elected legislatures. Denmark did have a party, but it seems to have merged into a larger party with a focus on environmentalism rather than explicitly animal welfare (23).

5.2 Method: How we forecast the chance of winning a seat

In this report, we are interested in finding additional legislatures where animal parties could win seats.

Proportionally-elected legislatures have an election threshold - this is the minimum vote required for a party to win at least one seat in an election. Some legislatures have legally set thresholds, while others have de facto thresholds determined by the number of seats available. For example, if a legislature has 20 seats, then a party would usually need to win around 5% of the vote to win a seat; but if a legislature has 200 seats, then the party would usually only need to win 0.5% of the vote. Of course, this rule of thumb is influenced by the specific election system used in a jurisdiction: there may be a legal minimum threshold (which would increase the vote required to win at least one seat); voters may be divided into multiple constituencies (which would usually increase the threshold required); votes may be transferable and cast by ranking candidates (which would usually decrease the threshold required); and so on. For our analysis, we estimate a rough ballpark threshold for each legislature based on previous elections in that legislature (combined with any legal thresholds that may exist).

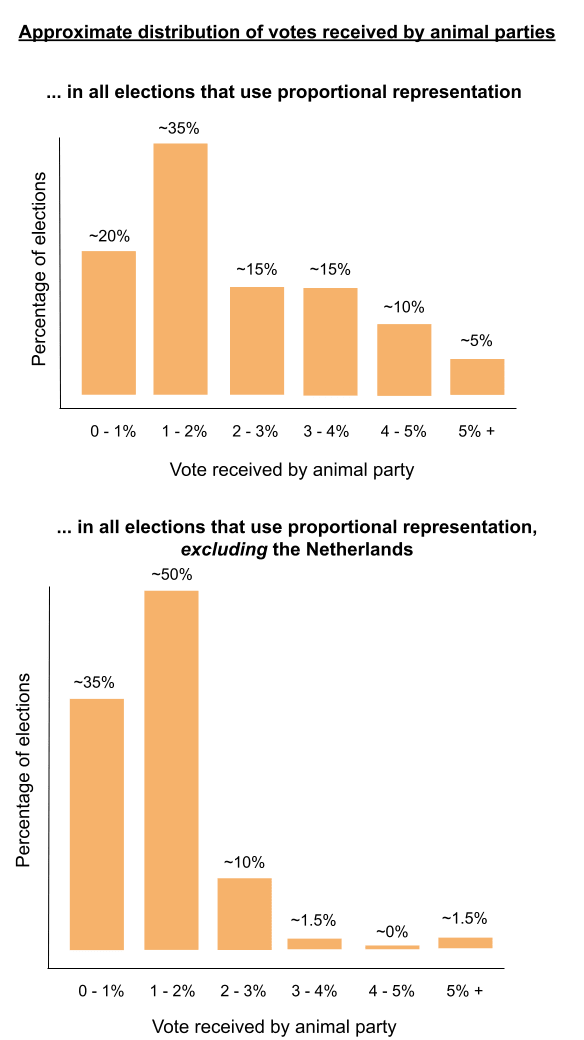

Now, how can we figure out if a new animal party might exceed the threshold necessary to win a seat? This requires making a prediction about what vote a new animal party might receive. Basically, the most agnostic way to predict a new party's vote is to look at the votes that have been received in the past by animal parties around the world.

The following graphs show the votes received by all animal parties around the world in elections that use proportional representation. We give rough percentages for the frequency with which votes are received in each interval. We have been quite aggressive in rounding these percentages, as we want to emphasise the fact that our forecasts are quite coarse in precision.

The top graph shows the raw data. For example, animal parties have received a vote between 0% and 1% in around ~20% of elections in our dataset.

However, there is one anomaly. The animal party in the Netherlands (Party for the Animals) has been extremely successful. This party has built its profile and support over time, and it now frequently receives votes that are unrealistic for new parties to expect.

So, the bottom graph shows the same raw data but excluding elections in the Netherlands. In this more modest dataset, animal parties have received a vote between 0% and 1% in around ~35% of elections.

We do think that it is worthwhile giving some weight to the elections from the Netherlands in our data set. So, for our forecasts for future elections, we basically average the numbers in the above two graphs. This is equivalent to placing a weighting of 0.5 on all data points from the Netherlands, and a weighting of 1 on all other data points.

Our forecasts are summarised below in Table 2. The top half of the table shows the average of the numbers from the above graphs. The bottom half of the table turns these numbers into forecasts. For example, we would expect perhaps ~30% of elections to yield a vote for an animal party between 0% and 1%. This means that around ~70% of elections would yield a vote above 1%.

Therefore, if we imagine that animal parties ran in 10 independent elections, we would expect to see:

- 4 elections where the animal parties receive less than 1% of the vote

- 3 elections where the animal parties receive between 1% and 2% of the vote

- 1 election where the animal party receives between 2% and 3% of the vote

- 1 election where the animal party receives between 3% and 4% of the vote

- 1 election where the animal party receives between 4% and 5% of the vote

Imagine that a country runs an election that uses proportional representation and has a threshold of 1%. This means that any party receiving 1% of the vote will receive at least one seat. Our data shows that animal parties exceed 1% of the vote about 70% of the time. So, if an animal party contested this election, there would be a 70% chance of receiving a seat. This means that running in this election yields the movement around 0.7 expected seats.

We do not adjust this forecast up or down based on local considerations. This is the biggest limitation of our forecasting method. However, in the report sections below, we do flag where we think the forecast should be adjusted slightly up or down.

This simple calculation does exclude the possibility of receiving multiple seats. This means that our "expected seats" numbers could be slight underestimates. However, we suspect that receiving multiple seats on the first go is unlikely in practice. Other factors - such as limitations in our simple dataset - are far more important for the accuracy of our forecasts.

Table 2: How we convert past election results from existing animal parties to future forecasts for new animal parties.

Vote category | Proportion of elections where animal parties received this vote (all countries, though Netherlands weighted at half) |

0 - 1% | ~29% of elections |

1 - 2% | ~43% of elections |

2 - 3% | ~11% of elections |

3 - 4% | ~9% of elections |

4 - 5% | ~5% of elections |

5 - 6% | ~2% of elections |

6% + | ~0% of elections |

Minimum vote | Proportion of elections where animal parties exceeded this minimum vote (all countries, though Netherlands weighted at half) |

1% + | 70% of elections |

2% + | 27% of elections |

3% + | 16% of elections |

4% + | 7% of elections |

5% + | 2% of elections |

6% + | ~0% of elections |

5.3 Results: Our predicted chances of winning a seat for existing parties

The following table lists all animal parties that exist in countries with proportionally-represented legislatures, including those parties that have not yet won a seat. The table also gives an idea of whether those parties are running in all available proportionally-represented elections (including all regional/state elections rather than solely national elections).

Based on this analysis, the countries that seem most promising are:

- Brazil

- Chile

- Israel

- Switzerland

Table 3: Countries that use proportional representation and have an existing animal party.

Country | Party | Proportionally-elected legislatures in the country | Minimum vote to win a seat (rough %, ballpark from previous elections) | Are there elections that the party is not yet contesting? | What is the chance that we would win at least one seat here? | What is our forecasted expected number of seats here? |

Australia | Animal Justice Party | Senate (national UH) | ~5% | No | - | - |

6x state/territory upper houses* | ~2-4% | No | - | - | ||

Austria | Animal Rights NOW | National Council (national LH) | ~4% | No | - | - |

9x regional Landtags (UC) | ~4% | Yes | 7% per legislature (9x) | 0.6 | ||

Belgium | DierAnimal | Chamber of Representatives (national LH) | ~1% | No | - | - |

~4x regional parliaments (UC) | ~2-4% | Yes | - | - | ||

Brazil | Animal Party of Brazil (Partido Animalista) | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | ~2% | Yes | 27% | 0.27 |

27x state/district legislatures (UC) | ~1.5% (4x) ~2% (4x) ~3% (7x) ~4% (11x) ~5% (1x) | Yes (27x) | 30% per legislature (4x) 27% per legislature (4x) 16% per legislature (7x) 7% per legislature (11x) 3% (1x) | 4.3 | ||

Chile | Animal Party of Chile (Partido Animalista de Chile) | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | ~1% | Yes | 70% | 0.7 |

Senate of the Republic (national UH) | ~2% | Yes | 27% | 0.27 | ||

Cyprus | Animal Party (Κόμμα για τα Ζώα Κύπρου) | House of Representatives (national UC) | ~4% | Yes | 7% | 0.07 |

Finland | Animal Justice Party of Finland (Eläinoikeuspuolue) | Parliament (national UC) | ~3% | No | - | - |

Åland Legislative Assembly (regional UC) | ~3% | Yes | 16% 🔽 | 0.16 🔽 | ||

France | 1. Ecological Revolution for the Living 2. Animalist Party (Parti animaliste) | 12x regional assemblies (UC) | ~10% | Yes (11x) | 0% | 0 |

Germany | 1. Human Environment Animal Welfare Party (Partei Mensch Umwelt Tierschutz) 2. Action Party for Animal Welfare (Aktion Partei für Tierschutz) | Bundestag (national LH) | ~5% | No | - | - |

16x state parliaments (UC) | ~5% | No | - | - | ||

Greece | Animal Party (Κόμμα για τα Ζώα) | Vouli ton Ellinon (national UC) | ~3% | Yes | 16% | 0.16 |

Ireland | Party for Animal Welfare | Dáil Éireann (national LH) | ~1% | No | - | - |

Israel | Justice for All Party | Knesset (national UC) | ~3.5% | Yes | 27% ⬆ | 0.27 ⬆ |

Italy | Italian Animalist Party (Partito Animalista Italiano) | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | ~2% | No | - | - |

Senate of the Republic (national UH) | ~2% | No | - | - | ||

20x regional councils (UC) | ~4% | Yes (7x) | 7% 🔽 per legislature (7x) | 0.5 🔽 | ||

Moldova | For People, Nature and Animals (Pentru Oameni, Natură și Animale) | Parliament (national UC) | 5% | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

The Netherlands | Party for the Animals (Partij voor de Dieren) | House of Representatives (national LH) | ~1% | No | - | - |

12x provincial councils (UC) | ~2-3% | No | - | - | ||

New Zealand | Animal Justice Party Aotearoa New Zealand | House of Representatives (national UC) | ~5% | No** | - | - |

Portugal | People-Animals-Nature (Pessoas-Animais-Natureza) | Assembly of the Republic (national UC) | ~1% | No | - | - |

2x autonomous regional assemblies (UC) | ~2% | No | - | - | ||

Spain | Animalist Party with the Environment (PACMA) | Congress of Deputies (national LH) | ~1% | No | - | - |

~19x regional parliaments (UC) | ~2% (8x) ~3% (3x) ~5% (8x) | No | - | - | ||

Sweden | Animals' Party (Djurens parti) | Parliament (national UC) | ~4% | Yes | 7% 🔽 | 0.07 🔽 |

Switzerland | Swiss Animal Party (Tierpartei Schweiz) | National Council (national LH) | ~1% | Yes | 70% | 0.7 |

Council of States (national UH) | Yes | |||||

~26 canton councils (UC) | ~1.5% | Yes | 30% | 8 | ||

Uruguay | Green Animal Party of Uruguay (Partido Verde Animalista) | Chamber of Representatives (national LH) | ~2% | No | - | - |

Chamber of Senators (national UH) | ~3% | No | - | - | ||

United Kingdom | Animal Welfare Party | 3x devolved country legislatures (UC) | ~2% (1x) ~5% (2x) | Yes (3x) | 27% 🔽 (1x) 3% 🔽 per legislature (2x) | 0.3 🔽 |

United States | Humane Party | - | - | - | - | - |

Turkey | Animal Party (Hayvan Partisi) | Grand National Assembly (national UC) | ~7% | Yes | 0 | 0 |

LH = lower house; UH = upper house; UC = unicameral

*Tasmania is the exception, where the lower house is the one elected using proportional representation.

**New Zealand's Animal Justice Party is a new party. We have been in contact with them, and they plan to contest the 2023 general election.

⬆ denotes that our forecast would probably be higher than the stated percentage, given local considerations (e.g. support for animal welfare in Israel)

🔽 denotes that our forecast would probably be lower than the stated percentage, given local considerations (e.g. observed elections within that country)

6. Future Parties: Where Could Future Animal Parties Be Established?

6.1 Where do animal parties not yet exist?

We looked at all countries where animal parties do not yet exist. For each of those countries, we asked whether it would be worthwhile to form a new animal party.

We limited our analysis to countries ranked as "Full democracy" or "Flawed democracy" in The Economist Democracy Index (25). We only included legislatures that use some form of proportional representation. We attempted to capture all national and subnational legislatures. For subnational legislatures, we attempted to find all subnational legislatures that are genuine regional/state legislatures rather than city councils. The difference is not always clear cut. We found subnational legislatures in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, India, Malaysia, Switzerland, the United States, Italy, Spain, Greece, France, United Kingdom, Netherlands, South Africa, and Portugal (though only some of those legislatures use proportional representation). We decided against including the subnational bodies in Taiwan and New Zealand (which appear closer to city councils), Greece (which do not seem to have their own legislatures), and Indonesia (where we were limited by information).

6.2 Results: Our predicted chances of winning a seat for future parties

Based on this analysis, the countries that seem most promising are as follows, roughly ordered from most promising to least promising:

- South Africa

- Argentina

- Japan

- Norway

- Albania

- Colombia

- Sri Lanka

- Dominican Republic

Table 4: Countries that use proportional representation and do not have an animal party.

Country | Legislatures in the country | Minimum vote to win a seat (rough %, ballpark from previous elections) | What is our forecasted probability that we would win at least one seat here? | What is our forecasted expected number of seats here? |

Cape Verde | National Assembly (national UC) | ~4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Costa Rica | Legislative Assembly (national UC) | ~4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Czechia | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Denmark | People's Assembly (national UC) | ~3% | 16% | 0.16 |

East Timor | National Parliament (national UC) | ~4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Estonia | Riigikogu (national UC) | ~8% | 0% | 0 |

Iceland | Althing (national UC) | ~6% | 0% | 0 |

Japan | House of Representatives (LH) | ~1% | 70% | 0.7 |

House of Councillors (UH) | ~2% | 27% | 0.27 | |

Latvia | Saeima (national UC) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Lithuania | Seimas (national UC) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Luxembourg | Chamber of Deputies (national UC) | ~4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Malta | House of Representatives (national LH) | ~17% | 0% | 0 |

Norway | Storting (national UC) | ~2% | 27%⬆ | 0.27⬆ |

Poland | Sejm (national LH) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Slovakia | National Council (national UC) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Slovenia | National Assembly (national LH) | ~4% | 7% | 0.07 |

South Africa | National Assembly (national LH) | ~1% | 70%🔽 | 0.7🔽 |

9x provincial legislatures (UC) | ~1% (3x) ~2% (2x) ~3% (3x) ~5% (1x) | 70% per legislature (3x) 27% per legislature (2x) 16% per legislature (3x) 3% per legislature (1x) | 3.2🔽 | |

South Korea | National Assembly (national UC) | ~3% | 16% | 0.16 |

Taiwan | Legislative Yuan (national UC) | ~6% | 0% | 0 |

Suriname | National Assembly (national UC) | ~2% | 27% | 0.27 |

Panama | National Assembly (national UC) | ~5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Argentina | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | ~0.5% | 90%🔽 | 0.9🔽 |

Philippines | House of Representatives (national LH) | 2% | 27% | 0.27 |

Colombia | Senate (national UH) | ~1% | 70%🔽 | 0.7🔽 |

Indonesia | People's Representative Council (national LH) | 4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Hungary | National Assembly (national UC) | 5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Bulgaria | National Assembly (national UC) | 4% | 7% | 0.07 |

Namibia | National Assembly (national LH) | ~1%, but ~7% in a constituency | 70%🔽🔽 | 0.7🔽🔽 |

Croatia | Parliament (national UC) | ~1%, but 5% in a constituency | 70%🔽🔽 | 0.7🔽🔽 |

Sri Lanka | Parliament (national UC) | ~1% | 70%🔽 | 0.7🔽 |

Montenegro | Parliament (national UC) | ~1% | 70% | 0.7 |

Romania | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | 5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Senate (national UH) | 5% | 3% | 0.03 | |

Albania | Parliament (national UC) | 1% | 70% | 0.7 |

Dominican Republic | Chamber of Deputies (national LH) | 1% | 70%🔽 | 0.7🔽 |

Serbia | National Assembly (national UC) | 3% | 16% | 0.16 |

Moldova | National Assembly (national UC) | 5% | 3% | 0.03 |

Lesotho | National Assembly (national LH) | ~2% | 27%🔽 | 0.27🔽 |

North Macedonia | Assembly (national UC) | ~1.5% | 30% | 0.30 |

LH = lower house; UH = upper house; UC = unicameral

🔽 denotes that our forecast would probably be lower than the stated percentage, given local considerations (e.g. limited track record of animal parties in the region; or a constituency-specific requirement)

⬆ denotes that our forecast would probably be higher than the stated percentage, given local considerations (e.g. solid track record of animal parties in countries with similar demographics)

7. European Parliament: Could Animal Parties Win More Seats in the European Parliament?

Could it be worthwhile to give greater assistance to animal parties contesting seats in the European Parliament? The European Parliament is a special case. In elections to the European Parliament, minor parties often receive disproportionately higher votes compared to their respective national parliaments (26,27). Also, many Member States have existing animal parties and/or high public support for animal welfare.

Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any low-hanging fruit for animal parties in the European Parliament. In all Member States where animal parties are not already contesting European Parliament elections, the minimum vote required to win a seat is quite high.

In the European Parliament, there are a number of animal parties that already hold seats. The parties from Germany (Human Environment Animal Welfare Party), the Netherlands (Party for the Animals), and Portugal (People-Animals-Nature) have won representation in this body.

Members are elected using proportional representation. Many Member States have legal thresholds, and other Member States have de facto thresholds given the relatively small number of seats contested in each Member State.

There are some Member States where a vote of ~5% is enough to win a seat (e.g. Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, and so on). These may be the most promising Member States in which to run, and we certainly encourage animal parties to contest these elections. However, the forecasted probability of winning seats even in these Member States appears insufficient to justify the immediate investment of resources.

Table 5: Elections to the European Parliament.

Member State | Party | Minimum vote to win a seat (rough %, ballpark from previous elections) | (For Member States with animal parties) Most recent observed vote for animal party | Are seats in this Member State currently uncontested by animal parties? | What is our forecasted probability that we would win at least one seat here? | What is our forecasted expected number of seats here? |

Austria | - | ~6% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Belgium* | DierAnimal | ~9% | 1.49% | Yes (2x electoral colleges) | 0% | ~0 |

Bulgaria | - | ~6% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Croatia | - | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Cyprus | Animal Party | ~8% | 0.79% | No | - | - |

Czechia | - | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Denmark | - | ~6% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Estonia | - | ~12% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Finland | Animal Justice Party of Finland | ~7% | 0.16% | No | - | - |

France | 1. Ecological Revolution for the Living 2. Animalist Party | 5% | 2.16% | No | - | - |

Germany | 1. Human Environment Animal Welfare Party 2. Action Party for Animal Welfare | ~0.5% | 1.45% | No | - | - |

Greece | Animal Party | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Hungary | (none) | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Ireland* | Party for Animal Welfare | ~7% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Italy* | Italian Animalist Party | 4% | 0.60% | No | - | - |

Latvia | (none) | ~7% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Lithuania | (none) | ~6% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Luxembourg | (none) | ~12% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Malta** | (none) | ~40% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Netherlands | Party for the Animals | ~4% | 4.02% | No | - | - |

Poland* | (none) | 5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Portugal | People-Animals-Nature | ~5% | 5.08% | No | - | - |

Romania | (none) | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Slovakia | (none) | ~5% | - | Yes | 3% | 0.03 |

Slovenia | (none) | ~11% | - | Yes | 0% | ~0 |

Spain | Animalist Party with the Environment (PACMA) | ~2% | 1.32% | No | - | - |

Sweden | Animals' Party | ~4% | 0.10% | No | - | - |

* denotes Member States that divide their electorate into multiple constituencies. This sometimes has the effect of increasing the de facto threshold necessary to win at least one seat, though this depends on the type of proportional representation used by the Member State to distribute seats.

**appears to be dominated in practice by two major parties

8. Track Record of Existing Parties

In this section, we focus on the five countries where an animal party has won election to a national or regional legislature: Australia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Portugal. We examine what impact these animal parties might be having on policy, as well as any important strategic considerations that we can identify.

8.1 Australia: Animal Justice Party (New South Wales)

We conducted an interview with Emma Hurst, who sits as a Member of the Legislative Council in New South Wales. This state, one of eight states and territories1 in Australia, has about 8 million people (30% of the population of Australia). The Legislative Council is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of New South Wales. The Legislative Council has 42 Members, and typically 21 of these are elected at a time. The Legislative Council contains a diverse collection of parties and has similar power to introduce and amend legislation to the lower house2. Hurst was elected in the 2019 election, representing the Animal Justice Party and receiving 1.95% of the first-preference vote3. The Animal Justice Party also has representatives in the Victorian state legislature, but our interview focused solely on the party's activity in New South Wales.

Hurst identifies her key policy wins as:

- The creation in June 2023 of an Animal Welfare Committee, with Hurst as the Chair, by a proposal from the ruling Labor party. This Committee will, for the duration of the current term of Parliament, "inquire into and report on matters relating to the welfare and protection of animals in New South Wales" (28)

- Higher penalties for people convicted of animal cruelty

- Outlawing the use of cetaceans in entertainment, meaning that businesses like Seaworld can never set up in NSW

- A requirement that animal shelters must make efforts to rehome animals before euthanizing them

- A requirement for cats and dogs used in scientific experimentation to be rehomed rather than killed once the experimentation is finished

- Over $60 million in Government funding towards rescue organisations, greyhound rescues, Lucy's Project (an organisation that supports people with animals experiencing domestic violence), and the enforcement of animal cruelty laws

- Changing the laws around violent fetish videos and around bestiality, i.e. an automatic ban on keeping further animals for people found guilty of these crimes. Likewise, people guilty of serious animal cruelty can no longer work with animals (e.g. zoos) or pass working-with-children checks (required for jobs and volunteer roles involving children)

Hurst has also been a Chair, Deputy Chair, or Member in a number of other parliamentary committees (29).

Our interview also identified some other key points, which are as follows:

- Hurst has had success in both proposing and amending legislation. For proposing legislation, this is most successful when Hurst can identify which government MPs may be most sympathetic to the proposed law, as those MPs can then advocate for the proposed law within the ruling party. In other cases, Hurst has proposed legislation and launched a strong media campaign. If there is sufficient support for the proposed legislation among the Legislative Council and the public, the government is incentivised to propose a near-identical piece of legislation in the Legislative Assembly, which results in the success of the policy. Amending proposed legislation can also be a successful strategy, because if an amendment to a Government Bill is agreed to by a majority of members in the Legislative Council, the Government is forced to either accept that amendment, or they may not be able to pass their own Bill. In this way, passing an amendment to a Bill can convince the Government to come to the table and negotiate on an issue.

- The biggest roadblock limiting Hurst's work is the power of the animal agribusiness industry and their lobby groups. Another roadblock is the fact that the animal welfare portfolio is under the jurisdiction of the Minister for Agriculture, which significantly hinders policy reform (see our detailed report on this challenge here). These two roadblocks make it very challenging for Hurst to secure ambitious, large-scale reforms for farmed animal welfare. Nevertheless, Hurst does campaign for some specific farmed animal welfare issues. Hurst sees value in the attention that these campaigns draw in both the media and in parliament, which can gradually help to build support among the public and other MPs in the long-run.

- Hurst has no data on whether, or by how much, advertising during election campaigns helps the Animal Justice Party's vote. She does report that the party's vote has increased in New South Wales over time. She also feels that advertising for specific campaigns has directly led to policy wins in those campaign areas before.

- Hurst reports that being an elected MP is an enormous help in securing media attention. She now finds it much easier to get stories into the media than in her previous roles in animal advocacy organisations.

- When asked if she would like the animal advocacy movement to do anything differently, Hurst spoke strongly about the movement's need to become more involved in political lobbying. Hurst has witnessed a disproportionately low amount of lobbying for animal issues compared to other issues in Australia. This is true for lobbying legislators to both propose pro-animal legislation and support pro-animal legislation proposed by other legislators. Hurst hopes this trend will change with the establishment of the new Australian Alliance for Animals, who have a focus on political lobbying.

8.2 Belgium: Victoria Austraet, Independent

We conducted an interview with Victoria Austraet, who sits as an independent deputy in the opposition of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region. This region is one of three in Belgium and has about 1.2 million people, 11% of the population of Belgium. The 89 deputies in this Parliament are elected using proportional representation, and the Parliament has a multi-party system. Austraet was elected in the 2019 election, where she represented the party DierAnimal and received 1.32% of the vote. Austraet subsequently left the party and now sits as an independent.

The key findings from our interview are as follows:

- Since the Brussels Parliament has a multi-party system, Austraet can propose both laws and resolutions and have a good chance of them successfully passing. Passing any proposal requires discussions with the other parties to ensure support before the text is written. (This point may seem trivial to European readers, but in many majoritarian, two-party systems like Australia, it is extremely rare for a bill to pass unless it was submitted by the government.)

- When we asked about Austraet's concrete policy wins, the two main examples she cited were: a new law that bans the capture and killing of wild pigeons; and a resolution to ask the minister to pressure EU policymakers to ban long-distance transport of farmed animals.

- However, Austraet independently made the point that her most significant work is to simply raise animal welfare and veganism as issues in Parliament. Raising animal issues on the agenda makes them more legitimate as issues and encourages the other deputies (and the Minister) to shift in the right direction over time. Austraet felt strongly that while this effect is difficult to measure, it is real and important.

- Austraet emphasises that it is essential to develop good relationships with other parties and with the Minister responsible for animal welfare. In particular, being an independent deputy enables Austraet to develop these relationships without the interference of a party label or a party apparatus.

- Austraet has encountered a few key roadblocks during her term as a deputy. 1) Firstly, the Minister responsible for Animal Welfare has a large amount of control over the details of animal welfare laws and even how proposed laws are discussed. 2) Secondly, the Minister has stated that he will soon release a new, overarching welfare code, and many parties are reluctant to support Austraet's proposals while the details of the Minister's code remain unknown. This compounds a general reluctance from the other deputies to support animal welfare reforms. 3) Thirdly, Austraet is part of the opposition, rather than the government coalition. The first of these roadblocks (1) is a specific feature of the Brussels political system. The second (2) and third (3) of these roadblocks are specific features of the current policy agenda and makeup of Parliament, and may not necessarily interfere with progress in future sessions of Parliament.

- Despite these roadblocks, we discussed with Austraet the role of party politics in animal advocacy in general. At the end of our interview, Austraet emphatically argued: "People in animal welfare should really go into politics. [...] We have to be there."

8.3 France: Ecological Revolution for the Living (REV)

We conducted an interview with Victor Pailhac, who is a staff member of France's party REV (Ecological Revolution for the Living). The REV has one elected representative, Aymeric Caron, in France's National Assembly (the lower house of a bicameral legislature). Caron won election in 2022 as part of the left-wing political alliance NUPES (Nouvelle Union populaire écologique et sociale), receiving 45.05% (first round) and 51.65% (second round) of the vote in France's two-round runoff system. Victor Pailhac, who responded to our questions via email, works for REV and has also run as a candidate in elections.

The key findings from our interview are:

- REV considers its main victories so far to be shifting the political discourse and moving "antispeciesism" and "radical ecology" from eccentric topics to terms regularly used by other politicians and the media.

- REV has made progress in the abolition of bullfighting and intends to complete this campaign to abolish bullfighting in France.

- REV's main strategy involves disseminating information, argumentation, and public education, which they see as the only way to convince politicians and citizens to listen. REV also unites with political partners, such as the left-wing party La France Insoumise (also part of NUPES) to make short-term progress. For example, the alliance with La France Insoumise is an important part of the campaign against bullfighting.

- The main roadblocks facing REV is the lack of financial resources. Other roadblocks include the power of lobbies, certain government policies perceived as anti-democratic, and negative media coverage of the far-left (by political opponents).

8.4 Netherlands: Party for the Animals

For the Party for the Animals in the Netherlands, we have derived a list of main policy achievements from the party's website (30). We have not checked how these policies have been implemented/enforced or whether any of these would have happened even without the party's involvement. This list is a subset from the larger list on the party's website - we simply chose the achievements that seem to us like fairly high-impact.

- More frequent monitoring of animal welfare on farms (2006)

- Ban on enriched cage (before farmers had invested in enriched cages) (2006)

- Recording of scientific tests conducted on invertebrates (2006)

- Inclusion of animal welfare in the criteria for Corporate Social Responsibility (2007)

- Mandatory CCTV surveillance in livestock markets (2008)

- National moratorium on "mega stalls" (2011)

- Ban on killing eels in a salt bath without stunning (2011)

- Ban on fur farming (2012)

- Enforcement of the ban on beak trimming of chickens (2012)

- Stricter regulations on animal testing (2013)

- End of export of calves to Turkey (2013)

- End of tail docking of piglets (2014)

- Ban on neonicotinoid pesticides (2014)

- Ban on electric shocks to tethered cows (2014)

- Ban on killing geese for carnival games (2014)

- Inclusion of animal welfare as a responsibility for the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (2014)

- Ban on slaughtering chickens using live hanging lines (2014)

- Installation of CCTV surveillance in slaughterhouses (2017)

- Mandatory grazing for cows (2017)

- Council-provided catering must be vegetarian by default in Amsterdam (and later in Zutphen and Eindhoven) (2019)

- Ban on mink breeding for fur (2020)

- Decrease in pace of slaughter in slaughterhouses (2020)

- Ban on mutilations of farmed animals and a requirement for animals to be able to express natural behaviour (2021)

- Requirement for chickens to have permanent access to water (2021)

- Stricter control and enforcement at reptile fairs and markets (2021)

- Ban on hunting hares and rabbits for pleasure (2021)

- Ban on branding of cows (2022)

- Requirement for the minister to oppose the live transport of animals to non-EU countries (2023)

- Ban on hunting for any reason in Groningen (2023)

Also, Otjes (3) calculated that the party's entry into parliament roughly doubled the amount of attention given to animal welfare and animal agricultural issues in motions and parliamentary speeches by other parties (this excludes the considerable attention given to these issues by the party's own prolific MPs). This is a meaningful result that may contribute to pro-animal policies gaining greater support in the longer term. The importance of salience inside the legislature is supported by the above three interviews from Australia, Belgium and France, and we emphasise that this is an important source of impact in our cost-effectiveness analysis below.

8.5 Portugal: People-Animals-Nature (PAN)

For the party PAN (People-Animals-Nature) in Portugal, the main policy achievements are provided in the dissertation by Sandler (31). Sandler lists the party's achievements starting from winning their first seat in the unicameral Assembly of the Republic up until mid-2021. Here, we list all of the achievements listed by Sandler. We order these achievements according to our rough expectation about their impact, from most impactful to least impactful:

- Allocation of nine million Euros to kennels and animal protection organisations, added to the 2020 state budget (two million Euros) and the 2021 state budget (seven million Euros)

- Requirement for all public canteens to have at least one vegan option, specifically covering "public schools, universities, hospitals, prisons, nursing homes, municipal buildings, and places of social services of public administration", passed in Parliament on 3 March 2017

- Ban on kill-shelters in Portugal, effective from September 2018

- Change in income tax law to allow people to claim pet medication as a deduction on their personal income tax, added to the 2020 state budget

- Establishment of a national strategy for stray animals, added to the 2020 state budget

- Change in the Civil Code to assign animals a "third legal" status, between legal things and legal persons, effective from 1 May 2017

- Ban on the practice of shooting birds as targets in captivity, passed in March 2021

- Ban on circuses using wild animals in Portugal, approved in October 2018 with a six-year transition period

- Higher fees for tickets to bullfighting shows, added to the 2020 state budget

- Ban on circuses using animals in the city of Funchal, passed at the end of 2014

- Stronger punishments for crimes against companion animals, approved in July 2020

- Law allowing companion animals to enter commercial establishments (subject to the permission of the business owner), effective from July 2018

This list excludes any policy achievements from mid-2021 to today. PAN also has a number of representatives at lower levels of government (e.g., municipal councils), so there may be small but meaningful policies that are missing from the above list.

9. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

9.1 Costs: Parties often pay for themselves

For launching or supporting a minor political party, the most important financial support will be the first grant. Ongoing support from foundations is rarely necessary.

Firstly, political parties have multiple sources of income (Table 6). The party would typically begin to receive income from these sources after running in the first election - the most important gap is therefore the money and other resources required to support the party during the first election. After that election, the party will have an easier time paying for itself. These sources of income include:

- Government funding for election campaigns. It is common for democratic countries to fund or reimburse political parties for election campaigns, though in some countries, receiving this funding is conditional on receiving a certain number of votes. All of our high-priority countries except for Switzerland provide government funding for election campaigns, though this typically requires surpassing 1% or 1.5% of the vote.

- Government funding for party expenses. When parties win seats, it is common for the government to fund both the salary of the parliamentarians and any expenses (e.g. staff salaries, travel expenses). All of our high-priority countries provide government funding for party expenses.

- Membership fees. The importance of membership fees depends on the party and the country. Most developed countries have witnessed a decline in party membership over time, and some countries have strict laws around private funding of political parties (e.g. Israel). On the other hand, Australia's Animal Justice Party has a disproportionately high number of members compared to its vote, perhaps suggesting that animal parties can attract a core of committed, paying members.

Table 6 shows whether these sources of income exist in each of our high-priority countries. The table does not include membership fees, as the importance of membership fees varies strongly from party to party.

Secondly, minor political parties are often run by volunteers - paid staff are usually limited to elected parliamentarians and their small teams, plus perhaps one or two executive or administrative staff hired by the party.

However, contesting an election and running a campaign costs money. Some important costs are:

- Salary for campaign staff if they need to take time away from paid work.

- Campaign expenses, such as travel costs and advertising fees.

- The fee or deposit required by the government to contest an election (Table 6). Among our high-priority countries, the only countries where electoral deposits are required are Japan and Sri Lanka, with the latter being very cheap (32). It is unclear if there are election deposits required to contest elections in Brazil and Chile, though we have searched and found no suggestion of election deposits in these two countries.

Due to Japan's prohibitively high deposit, and our projection that a party in Japan would win only ~1 seat, we do not consider Japan further. Japan has an extremely high deposit of 6 million yen (roughly $40,000 USD), which must be paid in order to compete for a seat in Japan's proportionally-represented House of Councillors (national upper house) (33). The deposit in Japan is returned to the party if the party wins a seat; otherwise, the deposit is lost (34). Japan's high deposit is an anomaly among developed countries, which typically either do not require a deposit or require a deposit of only a few hundred dollars (34).

For our analysis of the cost-effectiveness of minor political parties, we assume that the main costs would be the first two items on that list, i.e.:

- Salary. The salaries required would be for a small campaign and administrative team (e.g. two people) to work full time for the couple of months immediately before the election. This would vary by country depending on living expenses. For example, in Israel, roughly $18,000 USD would be sufficient for two people working full-time for two months (as Israel has a GDP per capita of around $55,000 USD).

- Campaign expenses. Again, different countries would require different amounts of money for travel, advertising, an online presence, and so on. Conservatively, we think that around $15,000 USD would be plenty, and many parties would be able to get away with much less.

This means that an initial grant somewhere in the ballpark of $30,000 USD would probably be sufficient for one election. If a party contests multiple elections (e.g. national and regional), additional money may be required. The costs of subsequent elections would probably be lower than this initial grant, as a) the parties would have some income from having run in elections already, and b) the party would already have a website, some advertising resources, and so on. For reference, Australia's Animal Justice Party spent around $75,000 USD in the 2022 South Australian state election (2), though that campaign involved deposits for 12 candidates (an expense that would not be required in our priority countries) and an ambitious and expensive advertising plan (an expense that we think is unnecessary, as argued in this report in section 3.2).

Table 6: Election funding system in the high-priority countries.

Recommended country and party | Expected result if funded | Does the government fund election campaigns? | Does the government fund expenses of parties that hold seats? (e.g. salary for MPs, staff budgets) | Cost to register as a party/candidate |

Switzerland (Swiss Animal Party) | ~8-9 seats (across regional + national legislatures) | No | Yes | No |

Brazil (Animal Party of Brazil) | ~2-5 seats (across regional + national legislatures) | Yes (requires approx. >1.5% of vote) | Yes | Probably not |

South Africa (new party) | ~4 seats (across regional + national legislatures) | Yes (requires winning at least one seat) | Yes | No |

Chile (Animal Party of Chile) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes | Yes | Probably not |

Israel (Justice for All Party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes (requires >1% of vote) | Yes | No |

Japan (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes | Yes | Yes Deposit of ~$40,000 USD, only returned if party wins a seat |

Argentina (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes (requires >1% of vote) | Yes | No |

Norway (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes (requires 2.5% of vote or winning a seat) | Yes | No |

Albania (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes (requires >1% of vote) | Yes | No |

Colombia (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes | Yes | No |

Sri Lanka (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes (requires >1% of vote) | Yes | Yes. Deposit appears to be under $100 USD. |

Dominican Republic (new party) | ~1 seat (national legislature) | Yes | Yes | No |

Source: IDEA (32)

9.2 Impact: Our rough back-of-the-envelope calculation

Here, we conduct some simple, back-of-the-envelope calculations to illustrate what the impact of winning a seat might look like. We will model the impact as follows: we assume that a new animal party is launched, and that party contests one election and has a ~70% probability of winning one seat in a legislature. That party holds the seat for one legislative term (say, four years) and then never holds a seat ever again.