Why you can justify almost anything using historical social movements

By JamesÖz 🔸 @ 2025-04-24T10:55 (+285)

[Cross-posted from my Substack here]

If you spend time with people trying to change the world, you’ll come to an interesting conundrum: Various advocacy groups reference previous successful social movements as to why their chosen strategy is the most important one. Yet, these groups often follow wildly different strategies from each other to achieve social change. So, which one of them is right?

The answer is all of them and none of them.

This is because many people use research and historical movements to justify their pre-existing beliefs about how social change happens. Simply, you can find a case study to fit most plausible theories of how social change happens. For example, the groups might say:

- Repeated nonviolent disruption is the key to social change, citing the Freedom Riders from the civil rights Movement or Act Up! from the gay rights movement.

- Technological progress is what drives improvements in the human condition if you consider the development of the contraceptive pill funded by Katharine McCormick.

- Organising and base-building is how change happens, as inspired by Ella Baker, the NAACP or Cesar Chavez from the United Workers Movement.

- Insider advocacy is the real secret of social movements – look no further than how influential the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights was in passing the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 & 1964.

- Democratic participation is the backbone of social change – just look at how Ireland lifted a ban on abortion via a Citizen’s Assembly.

- And so on…

To paint this picture, we can see this in action below:

Source: Just Stop Oil which focuses on…civil resistance and disruption

Source: The Civic Power Fund which focuses on… local organising

What do we take away from all this? In my mind, a few key things:

- Many different approaches have worked in changing the world so we should be humble and not assume we are doing The Most Important Thing

- The case studies we focus on are likely confirmation bias, where we are simply cherry-picking examples (consciously or subconsciously) that confirm our pre-existing beliefs. For example, people often don’t mention the examples where their chosen strategy failed to yield results (e.g. democracy protests which end in more authoritarian regimes or a local legal battle which leads to national legislation opposite to what you want)

- Be very sceptical when anyone, including ourselves, says that a strategy is “the most effective”

In reality, for almost every social issue, we have no clue what “the most effective” strategy is at any one time. The importance of context and relevance likely trumps lessons from previous movements (we have some research highlighting this!). As such, it makes sense to be open-minded to other approaches and not dogmatically preach your favourite strategy.

The response to this is not to think “oh let’s forsake doing research and learning from history” or “everything is equally effective” but rather, we should ask ourselves “Did I just find some notable examples that back up my beliefs or did I consider the most relevant social movements to my issue and methodically study the strategies used?”. (However, the rarity of this latter approach is one reason why the longer I’ve spent in the world of social movement research, the more jaded I’ve become about how research is used).[1]

In brief, I am advocating for more of us to drop our “soldier mindsets”, where we defend our beliefs against any evidence or arguments that might threaten them. Instead, we should adopt a scout mindset, where we seek to see things as they are, not as we wish they were.

I’ve fallen foul of this plenty of times. I remember times when I wanted to prove to someone that (for example) sugar is less worse than artificial sweeteners so I’ll google “is sugar worse than artificial sweeteners” then scan the links to find one that agrees with me. I don’t think I’m alone in this practice.

Julia Galef, author of “The Scout Mindset”, which I highly recommend reading, offers some tips and mindset shifts to support us:

- "Must I believe it?" rather than “Can I believe it?”

- In motivated reasoning, we disproportionately put our effort into finding evidence that supports what we wish were true. However, asking ourselves the simple question of "Must I believe it?" rather than “Can I believe it?” can prove powerful.

- The selective skeptic test: "Imagine this evidence supported the other side. How credible would you find it then?"

- Personally, I see many cases where advocates will repeatedly share a somewhat dodgy study that agrees with their beliefs but when there is a less favourable study, they will get into the weeds that the methodology wasn’t perfect, the sample size was too small, the authors overlooked some key considerations, and so on. In an ideal world, we treat all studies, regardless of result, with the same rigour!

- Hold your identity lightly

- One reason why it can be quite hard to engage with content that disagrees with your worldview is that you’ve constructed your entire identity around that worldview being true.

- For example, I lay out in a previous piece that if you’ve spent years campaigning using a particular approach, been arrested multiple times or taken other high-sacrifice actions, it can be very hard to admit you may have been wrong and all of that was unnecessary. To get around this issue, Julia Galef recommends “Holding your identity lightly means thinking of it in a matter-of-fact way, rather than as a central source of pride and meaning in your life. It's a description, not a flag to be waved proudly.”

- As one example, I’ve shifted away from labeling myself as “radical” or chasing “radical solutions”, so I can also think about ways to improve the world that allow for compromise, flexibility and incremental progress.

- I think there are some tensions with holding your identity lightly and taking high-sacrifice actions, which can be valuable. However, there are also significant downsides to being so fixated on a single worldview that you don’t change your mind when confronted with new evidence.

- Engage with people you disagree with

- This sounds obvious, but sadly, it is pretty common for people to become siloed within ideological containers (e.g. your friendship group, your workplace or your advocacy community). Deliberately engaging with people who don’t share your worldview can help you appreciate different perspectives and challenge your own thinking (and groupthink you may be subject to).

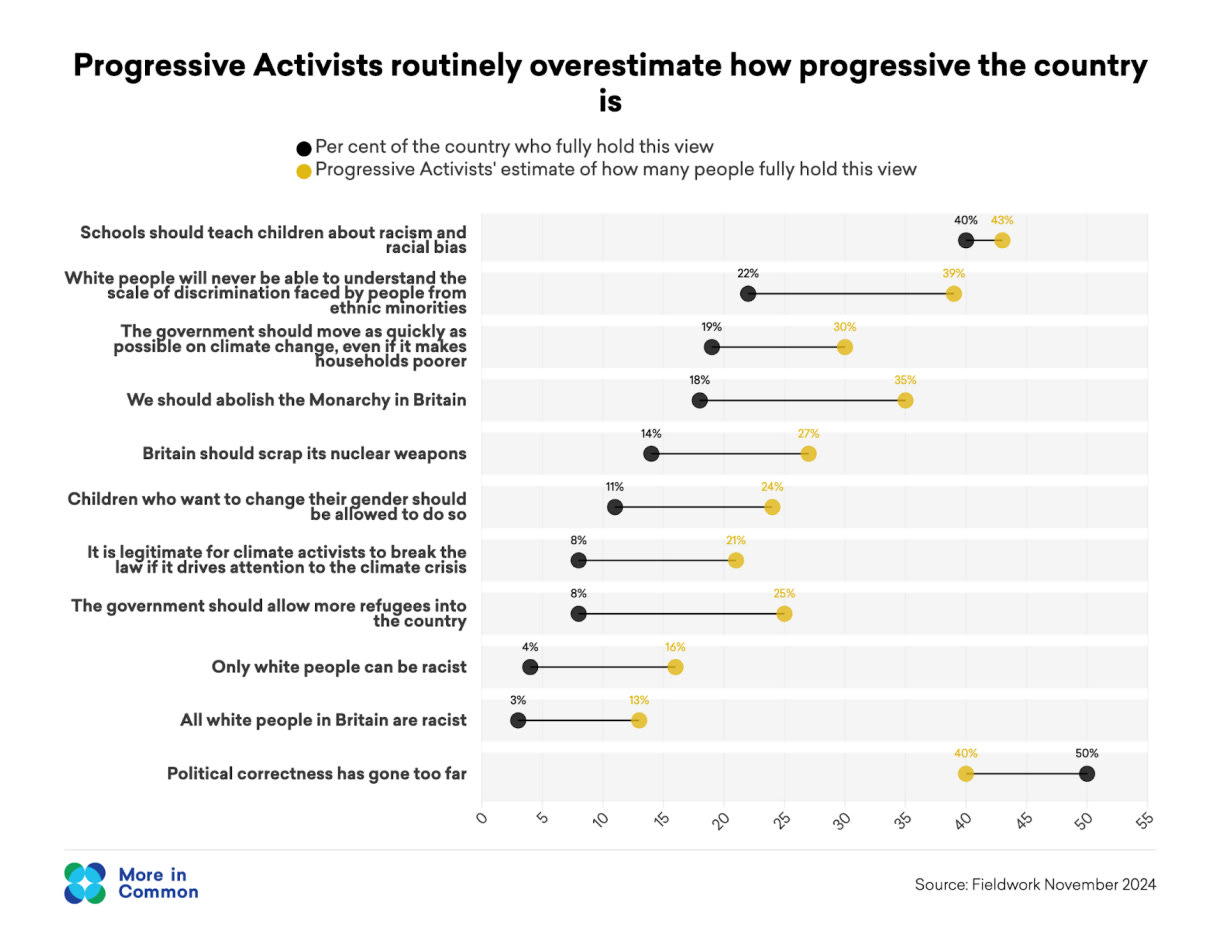

- One example of the consequences of not doing this is shown below in this research by More In Common, which shows Progressive Activists regularly overestimate how much of the country agrees with them.

- Not engaging with people you disagree with likely makes you a worse advocate for your issue, as you don’t fully appreciate their viewpoints and instead caricature them (as I often have done with NIMBYs, but this podcast did a great job of highlighting the very real concerns NIMBYs have which changed my mind on how to best approach NIMBYism).

For more on this, see a great summary of The Scout Mindset here. This essay was inspired by this comment from Lewis Bollard, making the same point in far fewer words!

- ^

As an aside, I think there are research methods that are more immune to this problem. For example, doing a literature review where, before you start, you have clearly specified inclusion criteria of what counts as relevant evidence and how you will weigh up the results. Or doing a pre-registration where you clarify how you will carry out and analyse an experiment before you even collect results. We at Social Change Lab do this for all of our experiments and polling projects (e.g. here).

D0TheMath @ 2025-04-24T15:28 (+60)

I think this post is a bit too humble. The social movements that worked had reasons they worked. The structure of the problem, the allies they were likely to find, and the enemies they were likely to have resulted in the particular strategies they chose working. Similarly for the social movements which failed. These are reasons you can & should learn from, and your ability to look at those reasons is the largest order effect here.

Most movements don’t, they do what you describe, choose their favorite movement, and cargo-cult their way to failure.

The most clear-cut version of this are climate activists doing a civil disobedience.

Why did civil disobedience work during civil rights? Well there were laws which used disproportionate levels of ugly violence to prevent people from doing a variety of very peaceful acts such as sitting on certain seats. By breaking these laws, filming it, and peacefully accepting the consequences you can show both how horrible the law is, how nice your movement is in comparison to the status quo, and how devoted you are to your opinion on the subject by being a willing martyr.

Throwing soup at van gogh paintings have none of these attributes, so it is counter-productive.

JamesÖz 🔸 @ 2025-04-25T12:27 (+14)

The social movements that worked had reasons they worked. The structure of the problem, the allies they were likely to find, and the enemies they were likely to have resulted in the particular strategies they chose working. Similarly for the social movements which failed. These are reasons you can & should learn from, and your ability to look at those reasons is the largest order effect here.

I take the point about being too humble but I'm not sure I fully agree with this bit above! Specifically, I think there are some random factors around luck, personal connections and timing that play a big role. For example, the founders of Extinction Rebellion tried some very similar campaigns a year before Extinction Rebellion launched, with no huge success. Then, a year later, Extinction Rebellion exploded globally. Basically, I also think you can do everything "right" but still not succeed. That said, doing certain things do definitely increases your chances of success.

Throwing soup at van gogh paintings have none of these attributes, so it is counter-productive.

We have some research coming out soon on this, and interestingly, there doesn't seem to be a big negative impact on public opinion if a protest is more illogical (e.g. it's hard for observers to connect the actions of the protest with the goals of the group). The main driver seems to be how disruptive the protest is (e.g. blocking oil depots seems to have comparable effects to throwing soup) although the analysis here is still to be finalised.

SiebeRozendal @ 2025-04-25T13:18 (+6)

Specifically, I think there are some random factors around luck, personal connections and timing that play a big role.

I don't think that this is a point against DoTheMath. It's just more information to learn from, but in this case learning that you can't just copy the method (if they were lucky) or need to develop/find the right personal connections etc.

D0TheMath @ 2025-04-25T15:33 (+1)

e.g. blocking oil depots seems to have comparable effects to throwing soup) although the analysis here is still to be finalised.

Interested to hear more, but I would not expect blocking oil depots to be effective either. Why would it? It may be related but its not so compelling to the average observer. Compare with the example I used, of sit-ins, which are eminently compelling. If you compare ineffective strategies with ineffective strategies you will pick up noise and low order effects.

Specifically, I think there are some random factors around luck, personal connections and timing that play a big role. For example, the founders of Extinction Rebellion tried some very similar campaigns a year before Extinction Rebellion launched, with no huge success. Then, a year later, Extinction Rebellion exploded globally.

I think we agree. Both for the successes and failures you should ask “was this a fluke?”, as you should always do.

JamesÖz 🔸 @ 2025-04-25T19:42 (+6)

Interested to hear more, but I would not expect blocking oil depots to be effective either. Why would it? It may be related but its not so compelling to the average observer. Compare with the example I used, of sit-ins, which are eminently compelling. If you compare ineffective strategies with ineffective strategies you will pick up noise and low order effects.

I mean there are probably a bunch of protests that you don't think make sense that had positive impacts (see some here) but specifically I would point to Extinction Rebellion blocking roads about climate or Just Stop Oil doing something similar.

I think we agree. Both for the successes and failures you should ask “was this a fluke?”, as you should always do.

I may be being obtuse but are you implying that Extinction Rebellion was a fluke? As if so, I don't agree with that! My view is that the founders had a pretty good design and plan, based on historical context and research, and with enough attempts, they managed to start something at the right time.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-04-25T15:52 (+3)

"Throwing soup at van gogh paintings have none of these attributes, so it is counter-productive."

What's the evidence it was counterproductive?

MichaelDickens @ 2025-04-25T16:33 (+3)

Piggybacking off of this to say that I recently looked at a lot of scientific literature on protests (for this post, although that post doesn't address the relevant evidence), and my current position is

- there is only limited evidence on whether the "throwing soup at paintings" genre of protests is effective

- if anything, the evidence suggests that it has a positive effect

I wouldn't confidently say that it has a positive effect, but I certainly wouldn't confidently say that's counterproductive, either, because the (very weak) evidence goes the other direction.

Holly Elmore ⏸️ 🔸 @ 2025-04-25T01:31 (+27)

As someone trying to start a social movement (PauseAI), I wish EAs were more understanding and forgiving that there isn't a great literature I can just follow. I feel confident that jumping in and finding my way was a good thing to do because advocacy and activism were neglected angles to a very important problem.

Most of my thinking and decision-making with PauseAI US is based on my world model, not specific beliefs about the efficacy of different practices or philosophies in other social movements. I expect local conditions and factors specific to the topic and landscape of AI and organizational factors like my leadership style to be more important than which approach is "best" ceteris parabis.

Ian Turner @ 2025-04-25T22:22 (+13)

Is it possible that organizations are privately deliberative, using a scout mindset to identify the best approach, but then publicly confident, projecting a soldier mindset to focus action, attention, funding, volunteers, etc., on the chosen model?

Social and political action are quite different from international aid funding, in that they are naturally adversarial. In such an environment it might not be best to project your uncertainties or vulnerabilities.

JoA🔸 @ 2025-04-25T18:57 (+8)

I appreciate this in part because the Lewis Bollard comment has stuck with me, but being a comment, it's just not ideal to link to when making this argument. It's nice to have a moderately concise and very readable piece making the same case with varied examples, coming from someone with an activist background who is less likely to get the charge that gets thrown around occasionally that EAs reject conventional social movements because they don't like the aesthetics, or because they just don't find it easy enough to run a CEA on them.

Bob Fischer @ 2025-04-24T11:56 (+6)

Correct and important. Thanks for sharing.

yz @ 2025-05-19T14:55 (+3)

This seems to be linked to a classic problem in social science research of finding causal factors. For the most effective strategies, one key is to focus on individual cases - in other words, key strategies are different for each different case, even if it is the same cause area (but for example in different regions.) This do require lots of manual/field research to find nuances, in my own opinion.

SummaryBot @ 2025-04-24T16:07 (+1)

Executive summary: This exploratory post argues that many social change advocates selectively invoke historical movements to justify their preferred strategies, cautioning that no single approach is universally “most effective” and urging a more open-minded, evidence-based, and context-sensitive mindset in advocacy work.

Key points:

- Historical social movements can be used to support nearly any theory of change—civil resistance, technological innovation, organizing, insider advocacy, and democratic participation all have supporting case studies—making it easy to confirm pre-existing beliefs.

- Advocates often cherry-pick examples that support their strategy while ignoring failures or contradictory evidence, creating a form of confirmation bias in how history is used.

- The author emphasizes humility, warning against confidently declaring one’s strategy as “the most effective” and instead suggests acknowledging uncertainty and the importance of context.

- Adopting a "scout mindset"—seeking truth over confirmation—is recommended, including tools like the “selective skeptic test” and “holding identity lightly” to reduce bias.

- Engaging with people who hold different views is important for avoiding echo chambers and improving one’s understanding of societal attitudes, as illustrated by survey data showing Progressive Activists often misjudge public opinion.

- While not dismissing historical learning or research, the author advocates for more rigorous, pre-registered methods (like literature reviews with inclusion criteria) to reduce motivated reasoning in movement strategy.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.