Why More EAs Should Work in Government

By policy_wonk @ 2025-09-09T13:54 (+18)

When people think about high-impact careers, government roles are often undervalued. The EA community has historically prioritized causes like global health, existential risk, and farmed animal welfare, areas where the problems are vast, neglected, and tractable. For each of these causes, there’s a crucial lever for change that we are underutilizing: working in government institutions.

To be clear, government work isn’t absent from EA’s radar. In fact, careers in AI governance, biosecurity policy, and nuclear safety, which are three of the top priorities on the 80,000 hours high-impact careers list, explicitly recommend government service.

So what’s missing?

While government work is discussed in some cause areas, working inside of government itself is not consistently treated as a core, cross-cutting priority. It’s often framed narrowly or adjacently to think tanks, diplomacy, or consulting on existential risk. But the truth is, the vast machinery of government touches almost every EA-relevant issue, from farmed animal welfare and global health to housing. These domains shape billions of lives and trillions in spending, and yet very few EAs are contributing high-impact work in the agencies and departments where much of that power is wielded.

That makes working in government a neglected and underexplored path, for every one EA working at a federal agency or state department, there are a dozen working in academia, nonprofit, or think tanks. If we want to influence systemic levers like law, regulation, and public funding for wide-spread and lasting change, we need far more EA-aligned professionals working within public institutions.

To illustrate what this could look like, a new nonprofit, Food Policy Pathways (FPP), launched earlier this year to help values-aligned professionals pursue government roles across the U.S. that shape our food system. Their theory is simple: if we want a more humane and resilient food future, we need the right people in government designing the policies that govern it, and which can impact billions of animal and human lives. FPP provides mentorship and free career coaching to help make that pipeline possible.

These efforts point to thinking of government policy in a broader way: government can be a major source of long-term funding and infrastructure for impactful work. While private philanthropy in farmed animal protection totals around $220 million annually, government funding towards these same goals, through grants, salaries, and institutional budgets, have the potential to dwarf that amount. By comparison, the budgets of public institutions like the USDA and NIH stretch into the billions each year, vastly outpacing what private grants can provide. While it’s true that not all of this capital can be redirected toward high-impact causes, the public sector remains an underleveraged resource for values-aligned work.

Of course, not all government roles are equally impactful. Entry-level staffer jobs, obscure agency positions, or narrow administrative roles may not offer immediate influence. But this isn’t unique to government, it’s true of any field. What matters is cultivating an ecosystem of EAs who are willing to do the slow, strategic work of building trust, learning institutional levers, and climbing the ladder toward durable influence. In turn, they can then go on to teach, guide, and uplift others following this path.

If 100 Effective Altruists were choosing their careers today, how many should enter government? At least 20? Probably more. The point is not to prescribe a number, but to reframe government work as essential infrastructure for EA goals, not just a side route.

So what do we need? We need existing organizations to support talent entering public institutions by adding available public service opportunities to job boards, and including the role of government as a lever for change at summits or conferences. We need greater funding to build these pipelines and sustain people in impactful roles, especially those that may not pay much but have the power to shape meaningful, long-term policy change. Just as crucially, we need more individuals willing to do the careful work inside the system, learning how institutions function and identifying points of influence over time. And we need broader recognition across the EA community that lasting progress often comes through public infrastructure, not just private innovation.

If this community is serious about scale, neglectedness, and tractability, we can’t afford to overlook government as a career path. It’s time to treat public institutions as core terrain for impact.

Seth Ariel Green 🔸 @ 2025-09-09T18:36 (+7)

A general question about this advice, and other pieces in the same vein: What areas should fewer EAs work in? We've got to come from somewhere.

More broadly, EA thinking places a high value on cost-benefit analysis. When talking about career stuff, that means opportunity costs. A version of that claim here would sound something like, "[some cause area] is oversaturated and could probably lose half of its current human capital without meaningful loss, which I believe for [reasons] and if those people moved into government and did [some stuff] then [good things] would happen..."

Without such a comparison, I'm afraid this case is not expressed in terms that EAs are likely to find persuasive.

Charlie_Guthmann @ 2025-09-09T19:50 (+2)

I feel like as a general rule of thumb, and this doesn't really fall on the gov/not gov axis but can be applied, too many EAs work in intellectual pursuits and not enough in power/relationship pursuits.

This isn't based on a numerical analysis or anything, just my intuition of the status incentives and personal passions of group members.

So e.g. I wouldn't necessarily expect the amount of EAs in government to be too low but maybe those working directly in partisan politics/organizing/fundraising to be too low. If I had to guess we are ~properly allocating towards policy makers both within think tanks and within executive branch orgs.

Seth Ariel Green 🔸 @ 2025-09-09T20:06 (+2)

Yes, I think there is something to this. We might have suboptimal talent distributions from a social POV if EAs are naturally attracted to certain kinds of work in a way that unconsciously/consciously influences career calculuses.

David_Moss @ 2025-09-09T19:04 (+5)

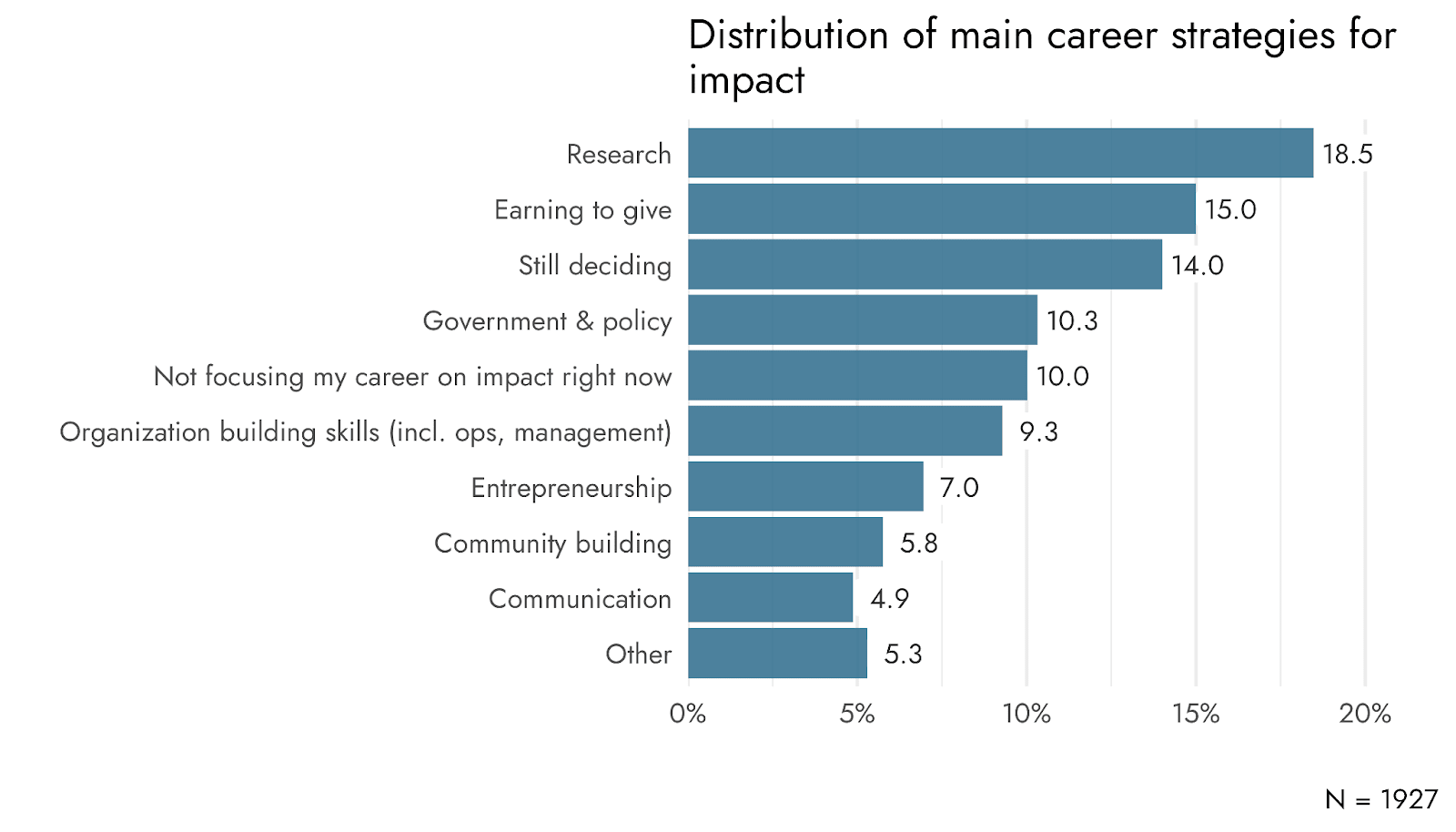

For reference, about 10% of EAs in the last EA Survey reported their career plan as working in government or policy. That's not very far behind the top categories, and it doesn't account for the 14% of respondents still deciding.

Brad West🔸 @ 2025-09-09T20:35 (+4)

Great piece! This connects directly to something I've been thinking about in my recent post on "orthogonal impact." The key insight isn't just that government roles have impact—it's that they often have the most impact through levers that aren't measured or incentivized by the job itself.

Consider the contrast: if you work at GiveWell or an EA-aligned charity, your performance metrics likely align with doing good. The counterfactual person who'd take your job would also be trying to maximize impact—that's literally what they're paid to do. But in government (or corporations, academia, etc.), the situation is different. A USDA official is evaluated on processing efficiency and regulatory compliance, not on whether they quietly shifted procurement standards to help millions of animals. A congressional staffer gets promoted for serving their boss well, not for adding crucial language to obscure bills that could save lives.

This misalignment between job incentives and impact opportunities is exactly what creates the leverage. The counterfactual government employee would likely focus on what gets measured—hitting their KPIs, avoiding controversy, climbing the ladder. They wouldn't spend political capital pushing for open data standards or championing unglamorous but vital legislation. These orthogonal opportunities for good sit neglected precisely because they don't help anyone's career.

Your point about government being "essential infrastructure for EA goals" is spot-on. We need people willing to occupy these positions and utilize both the official powers AND the unmeasured discretionary opportunities they contain.

lauren_mee 🔸 @ 2025-09-10T12:15 (+3)

I agree this is an overlooked career path, and one that many advising orgs (including historically my own) haven’t given consistent treatment.

My impression is that more EAs are working in government than we realise, and that many advising organisations do consider it highly impactful. The challenge is that government roles come with expectations of impartiality, so there’s a real limit to how openly funders or career groups can promote specific pathways without undermining credibility.

That said, I think we could do much more to bring policy conversations into spaces like EAGs. The community would benefit from normalising government service as a long-term route to influence, not just as an “adjacent” option.

For those interested, Impactful Policy Careers has done excellent work in the European context, though even we face restrictions on how openly they can be promoted.

Impatient_Longtermist @ 2025-09-09T18:30 (+3)

Completely agree with this analysis. For readers interested in a high impact career in the UK civil service I recommend checking out Impactful Government Careers. We offer 1:1 discussions and a weekly job mailing list of high impact roles in government.

Mo Putera @ 2025-09-09T18:06 (+2)

On this note, Probably Good's Civil Service in LMICs as a High-Impact Career Path is a great first stop for EAs from LMICs. Their job board is great too.

BearNavy @ 2025-09-09T18:23 (+1)

If you wanted to change the world, would you rather influence a $220M nonprofit budget, or a $220B government budget?