New Cause: Radio Ads Against Cousin Marriage in LMIC

By Jackson Wagner @ 2022-08-15T17:36 (+27)

This New Cause Area is brought to you by my newsletter, Nuka Zaria.

Reducing “kinship intensity” might give outsized boosts to a nation’s culture and economic productivity.

Although rare in western countries, marriage between first or second cousins still make up about 10% of all marriages worldwide. It’s well known that the children of closely-related relatives are at higher risk for genetic disorders. By itself, this might be a reason to discourage cousin marriages, as has been discussed previously on the Forum.

But the story quickly gets weirder. Some historians and academics think that when Western Europe shifted away from cousin marriage starting in the 1400s, this might have actually caused profound changes in the structure of European society — inadvertently creating a more individualistic, entrepreneurial, and high-trust culture which set the stage for the scientific and industrial revolutions.

How is it that some random medieval Church edicts against cousin marriage could possibly have had such powerful effects? The idea is explored in more detail in sources like Harvard professor Joseph Henrich’s book “The WEIRDest People in the World” (review here), and covered in articles like this one. The basic concept is that banning cousin marriage helped break up the power of kinship-based tribes (imagine the Capulets and Montagues of “Romeo & Juliet”), which changes the whole structure of the social graph: instead of rival houses, you get a more atomized individualism where people become more willing to cooperate across families. Quoting from the article above,

Before the Middle Ages, Europe was similar to other agrarian societies around the world: Extended kin networks were the glue that held everything together. Growing crops and protecting land required cooperation, and marrying cousins was an easy way to get it. Cousin marriages were even actively promoted in some societies because they kept wealth concentrated in powerful families.

Traditional kin networks stressed the moral value of obeying one's elders, for example. But when the church forced people to marry outside this network, traditional values broke down, allowing new ones to pop up: individualism, nonconformity, and less bias toward one's in-group.

The academic work here is speculative, but “big if true”, since it suggests the existence of a neglected lever for influencing long-term cultural outcomes.

If discouraging cousin marriage leads to such good outcomes, let’s keep doing it!

Lots of people have described the Industrial Revolution as "the best thing to have ever happened", "the most important event in human history", and so forth. Today, high levels of societal trust and high long-run economic growth rates are some of the most prized traits of the world’s most successful countries. So, how can we get more of a good thing?

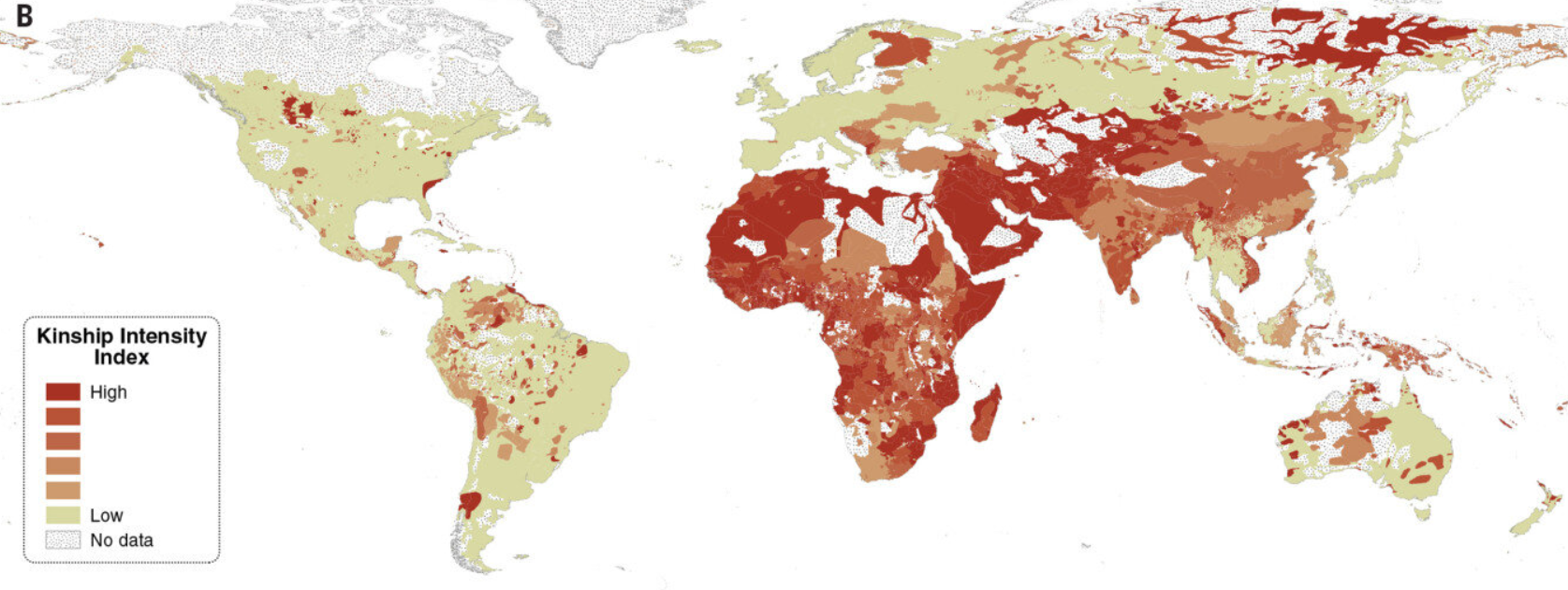

Since the medieval era, rates of cousin marriage have plummeted, not just in Europe but across the world, as societies changed their norms. But some places still experience very high rates of cousin marriage — it's most common in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia:

Existing public health efforts could cheaply warn about genetic harms from consanguinity.

So, if we want to slightly accelerate the ongoing global trend away from cousin marriage, and thereby accelerate the transition to a more high-trust, individualistic culture and a higher long-run economic growth rate for the civilizations of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, what should we do?

Obviously, EA has neither the authority nor the inclination to implement coercive bans on cousin marriage, like the Catholic Church did centuries ago. But there are already a number of charities (like Family Empowerment Media) that focus on disseminating public health information in developing countries. In-between their existing programming, I imagine it would be easy to add some material on the health downsides of children born to consanguineous couples. After they receive the information, people would of course be free to make their own voluntary choices.

A radio campaign (or some other effort) aimed at lowering the rate of cousin marriage seems like it would be cheap to try out, and its efficacy could be easily measured through standard RCT techniques. Of course, it would be harder to assess whether reduced rates of cousin marriage were really helping create a less tribal, more peaceful and prosperous society. But it seems at least worth trying out! Although it is potentially controversial, and although the payoff might take a long time to arrive (decades to centuries!), disincentivizing consanguinity might also be a powerful and neglected lever for improving the long-term future in a variety of ways.

Upsides of the idea:

- It seems like the whole intervention could be tried out very cheaply.

- It would be easy to test, via RCT, how well a public-awareness campaign actually reduces the rate of cousin marriage in an area. The idea could “fail fast” and be ditched early if it doesn’t work.

- If academics are right about the importance of declining consanguinity in European history, it might shift societies towards higher trust and greater individualism, which might increase long-run economic growth and human flourishing more generally.

- This could be particularly helpful in the Middle East and other areas in the troubled “arc of instability” region of weak governments and frequent wars/conflicts. Creating stabler, less tribal, more positive-sum societies there could help reduce “existential risk factors” for dangers like nuclear war.

- Africa's population is currently very fast-growing, so now is a good time to get the message out. Changes to the social graph today might have a disproportionate impact on the future, when Africa’s population is three billion.

- Some might see a campaign against cousin marriage as a campaign to proselytize European values in other countries, thus degrading their independence and cultural distinctiveness. This is a reasonable point. However, if discouraging consanguinity results in stronger and faster-growing societies, then I’d expect that in the long run we’d be empowering those regions on net, not undercutting them. After all, Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia are today some of the world's poorest regions, with the least say over humanity’s common destiny. If changing a few marriage norms could help give these regions a permanently higher long-run economic growth rate, it could lead to a fairer, less exploitative future (although potentially a more competitive and multipolar one) where the different regions of the earth are more equal in their overall levels of wealth, wellbeing, and capability.

- As a bonus, you’d also get the straightforward genetic health benefits!

Downsides of the idea:

- It would be very hard to measure whether reduced cousin marriage actually leads to broader improvements in society, since the effect is probably very slow-acting. The best we might be able to do is support further scholarly work to pin down how important cousin marriage really was for the rise of individualist culture and the industrial revolution.

- It might be controversial in the countries where the messaging is deployed, creating a backlash against the charities’ other public health messaging.

- It might be less controversial in southern India and sub-saharan Africa than in North Africa and the Middle East, where Islam is often considered to affirm the practice of cousin marriage.

- Hopefully, just informing people about the genetic health risks wouldn’t be nearly as controversial as directly crusading against cousin marriage as a cultural institution. But who knows!

- Alternatively, things might go fine in the target country, but the campaign might be controversial in the western philanthropic scene / on twitter / etc, and create a reputational hit to the EA movement.

- There are probably individual-level social benefits of cousin marriage for people living in societies where the practice is common — there must be, otherwise people wouldn’t do it! The stronger family ties (social and economic) created by cousin marriage are probably nice on an individual level, even if they create a troublesome and overly-tribal equilibrium for the broader society. People who forgo cousin marriage will get healthier children and contribute to a more flourishing society, but they’ll give up those personal social advantages.

- This idea is definitely a “patient longtermist” cause, since the benefits might not become significant for around 200 years! If you believe that we’re living in the “most important century”, then worrying about things like climate change or demographic shifts in the year 2100 is silly because their effects will be overshadowed by bigger trends like AI or human enhancement technology.

A patient-longtermist cause area, using the tools of neartermist global health & development.

Regardless of whether or not this wacky idea passes official cost-benefit muster and is deemed worthy of funding by Openphil or others, I find this cause area intellectually interesting for a couple of reasons:

- The idea of running a consanguinity-reduction campaign is to get the impact on the long-term cultural trajectory of future civilization, yet its methods would slot perfectly into ongoing “neartermist” global health & development efforts — working in some of the world’s poorest countries, doing public-health awareness campaigns via radio broadcasts, checking efficacy via RCTs. The existence of “longtermist causes using neartermist tools” (and vice versa — like developing malaria vaccines or nutrient-fortified rice using cutting-edge biotechnology) strikes me as an interesting area of overlap, where EA might be able to learn valuable lessons and apply sanity-checks to its prioritization efforts.

- It could also be an interesting example of “longtermism for people who don’t expect the future to get too crazy”. If you don’t believe that humanity faces significant X-risk or a is likely to develop transformative new technology anytime soon, but you still buy the idea that humanity’s far-future is overwhelmingly important[1], what should you do? Maybe you should put your money in a patient-philanthropy fund, or follow Tyler Cowen’s advice and just try to do whatever increases economic growth. But this idea might offer a relatively concrete pathway towards influencing long-run cultural change, which is otherwise notoriously difficult to think about.

- Often, “longtermism” seems to boil down to “preventing human extinction risks”, since the future is so uncertain that (besides reducing x-risks) it’s hard to tell what actions might help humanity in a million years. The few other ideas that come to mind — reducing the chances of totalitarian “lock-in”, reducing the odds of great-power conflict, etc — are themselves confusing, since it’s not always clear whether (for example) a hawkish or dovish stance is better for the cause of peace. I think it’s interesting to explore different longtermist ideas that go beyond x-risk mitigation, such as finding ways to durably improve long-run humanity’s long-run cultural trajectory. (See also the idea of archiving valuable information for the enjoyment of far-future civilization.)

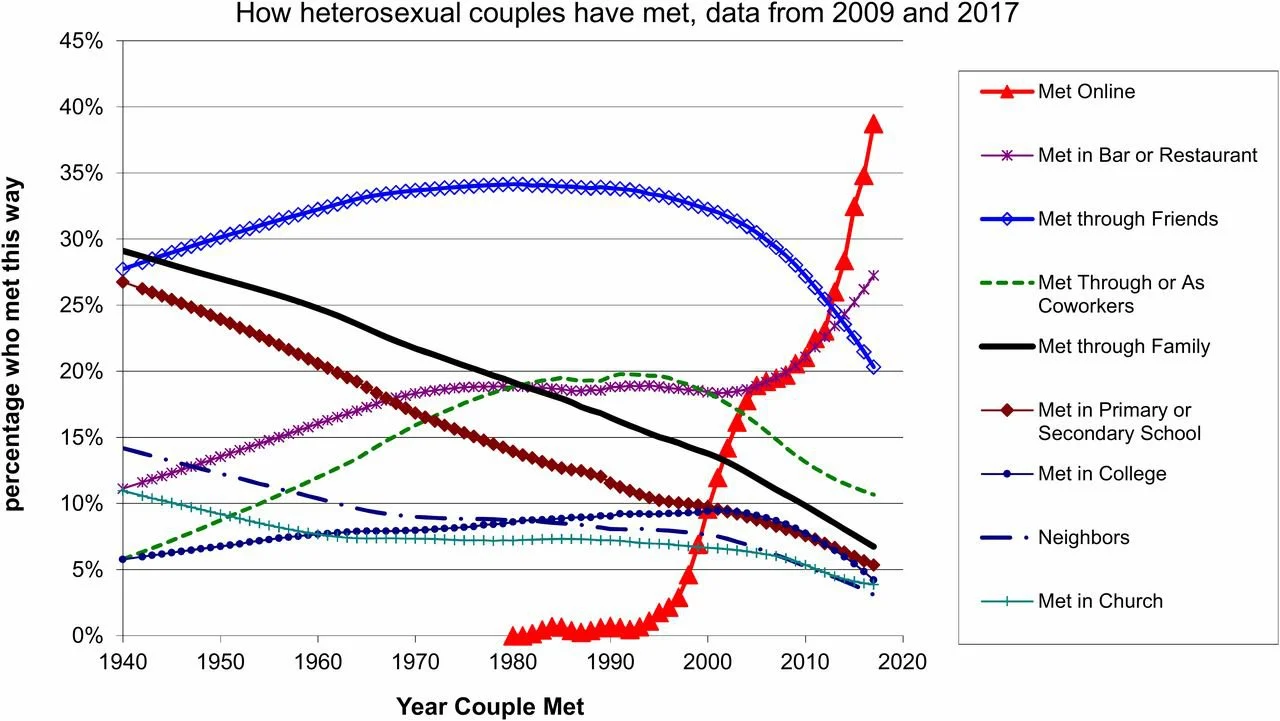

- There is not much cousin marriage anymore in developed nations. But we have certainly not arrived at the end of history when it comes to changing mating patterns, family structures, and societal social graphs. In recent years, people have shifted decisively towards meeting their partners on dating apps like Tinder instead of dating real-world acquaintances like coworkers. People all over the developed world are having fewer and fewer children, and they are also doing more and more “assortative mating” where people marry others of the same education/income level. Just like how the shift away from cousin marriage might have had outsized effects on culture by breaking up tribal-based societies, these modern-day shifts (which already have noticeable effects on some aspects of culture) might similarly lead to strange and out-of-proportion downstream changes to society’s values! Doing some RCTs on cousin-marriage-themed interventions in developing countries, and doing investigations into the idea that reduced consanguinity was an important factor in the development of western culture, might help give us insights that contribute to a broader understanding of how society’s social structure drives cultural change, and thus have a better understanding of where our own society’s values are headed.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, consider subscribing to Nuka Zaria.

- ^

To be clear, this is not a very popular combination of beliefs — many more people are skeptical of longtermist philosophizing and are worried about near-term X-risks like AI alignment!

lincolnq @ 2022-08-15T21:05 (+20)

I feel a bit uncertain of the sign, even if the impact is real. I'll be upfront that I haven't read the material, but figured I'd write this anyway mostly on priors.

I see two potential pitfalls:

First, I have a bit of a deontologist flag: the health downsides of consanguinity seem unrelated to the reason why you think the intervention would be important (which, according to you, is "creating a more individualistic, entrepreneurial, and high-trust culture"). I'd be worried about intentionally 'lying' to people (by focusing on the easier-to-sell message about health effects) in order to effect a cultural change; it seems vaguely undignified (I can point to all sorts of second-order bad ways that starting a misleading PR campaign could go wrong)

Second, "individualistic" culture is not obviously a good thing! Maybe it has some positive impact, for sure, but I can see ways in which Western individualistic culture leads (for example) to bad mental health outcomes which don't seem to be nearly as prevalent in more familial cultures. I'm not that thrilled that the kinship index definition you're using points at "co-residence of extended families" as a contributor.

PeterMcCluskey @ 2022-08-15T18:54 (+9)

My understanding of Henrich's model says that reducing cousin marriage is a necessary but hardly sufficient condition to replicate WEIRD affluence.

European culture likely had other features which enabled cooperation on larger-than-kin-network scales. Without those features, a society that stops cousin marriage could easily end up with only cooperation within smaller kin networks. We shouldn't be confident that we understand what the most important features are, much less that we can cause LMICs to have them.

Successful societies ought to be risk-averse about this kind of change. If this cause area is worth pursuing, it should focus on the least successful societies. But those are also the societies that are least willing to listen to WEIRD ideas.

Also, the idea that reduced cousin marriage was due to some random church edict seems to be the most suspicious part of Henrich's book. See The Explanation of Ideology for some claims that the nuclear family was normal in northwest Europe well before Christianity.

Jaime Sevilla @ 2022-08-15T20:36 (+7)

FWIW I reviewed and redid the analysis in Heinrich's paper.

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/wWGi4jTNNMhz2pHhJ/persistence-a-critical-review-abridged

The statistical relationship seems quite robust, but the analysis of causation is purely qualitative.

I am out of my depth assessing the psychological and historical evidence they cite, and it might well be true that kinship is an important component of it. However the usual standard for evidence in econometrics is a natural experiment, which they did not do.

Guy Raveh @ 2022-08-15T22:52 (+6)

-

So you want EA to promote an action (not marrying your cousin) claiming one goal (preventing genetic diseases) but having a hidden one that's different entirely (effect social change)? That doesn't sound like a good idea. We need to be honest about our intentions and goals.

-

So is it less cousin marriage, or potatoes, or the printing press that made Europe what it is today? There seem to be many competing theories, and not being a historian, I have no idea which one to believe.