Why Sanitation Matters for Global Health and Pandemic Preparedness

By Swan 🔸, SofiiaF @ 2025-10-01T13:41 (+16)

This post was cross-posted from Molecular Meditations by the Forum team. The author may not see comments.

Authors: Sofya Lebedeva and Sofiia Furman

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Qinyi Wang for providing feedback on this draft.

TL:DR: To work on this issue directly, apply to AIM (Ambitious Impact) as they are seeking applications to their charity entrepreneurship programs by October 5th 2025.

An Invisible Shield: How Sanitation Protects Us All

Whilst often overlooked [WHO 2024], sanitation quietly underpins both everyday wellbeing and the resilience to outbreaks of infectious disease. From reducing child mortality from diarrhoeal disease [NIH 2022] to robust systems used for detecting COVID-19 in wastewater [NIH 2023], sanitation underpins global health and pandemic preparedness.

Sanitation is recognised as a human right [UN-Water] and extends further than pipes and latrines- to dignity, security and robust public health systems. In an era of rising outbreaks and climate-modulated emergencies [NIH 2021, OWID 2024], where should sanitation improvements fall in our global health priorities?

What is sanitation?

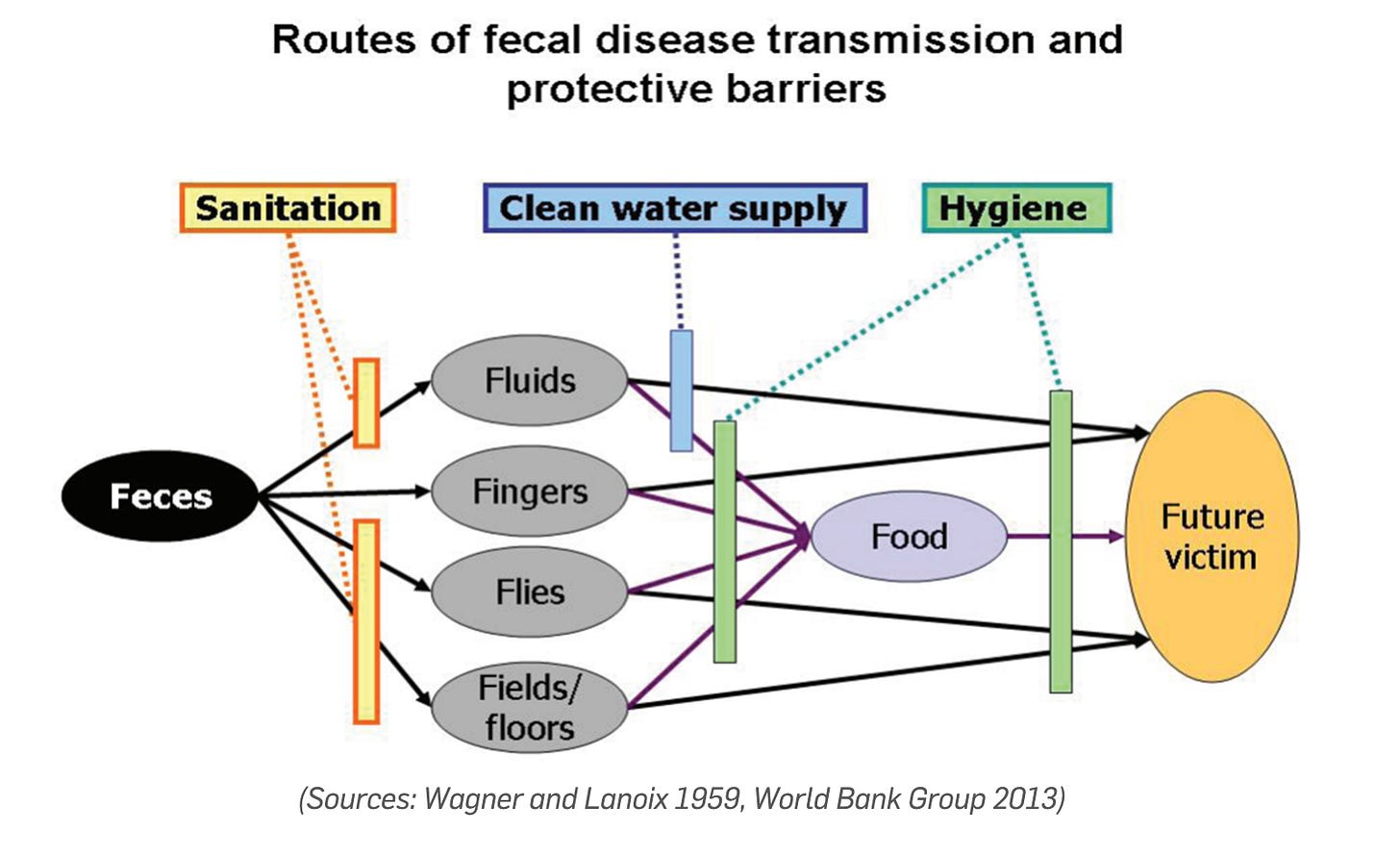

Sanitation is not just ‘clean water’- it is a system to manage human waste and prevent exposure to pathogens. [WHO 2024] From toilets and water pumps, [NIH 2022] to infrastructure that collects, processes and removes waste from households and communities [Nasim et al 2022]- sanitation sustains a safe and habitable environment. [UN 2018]

We can categorise sanitation initiatives into four domains:

- Household sanitation

- Access to toilets for waste and hygiene facilities [Tiwari et al, 2022]

- Institutional sanitation

- Facilities in schools, clinics, workplaces- ensuring public access [WaterAID 2019]

- Urban and environmental sanitation

- Infrastructure collecting, treating and removing individual waste inputs into a system- including sewers, faecal sludge management, wastewater treatment, pipe systems [Frontiers Vol8 City-Wide Sanitation 2020]

- Emergency sanitation

- Rapid systems used in crises- such as safe burial practices in outbreaks [CDC 2024]

These are not discrete domains - instead, improvement in population health hinges on all of these overlapping needs being consistently met.

The case for sanitation

Health Benefits

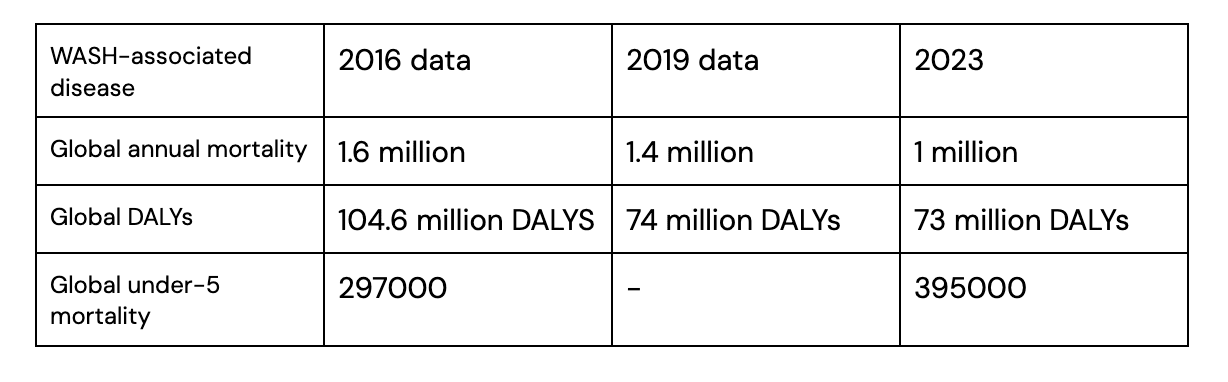

Poor sanitation increases the spread of pathogens, such as those that cause diarrhoea, cholera, helminths, and trachoma. These diseases disproportionately affect children, and a lack of clean water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths per year; however, exact figures are debated.

- One highly comprehensive study in the field [Prüss-Ustün, WHO 2019] calculated 1.6 million deaths in 2016 attributed to lack of WASH.

- The study also reported 104.6 million DALYs resulting from diseases due to a lack of sanitation.

- This study found that 60% of all diarrhoeal deaths worldwide were associated with a lack of WASH, and 297,000 deaths in children under 5.

- However, global health systems have changed significantly since 2016, and so more up-to-date studies can shed light on trends over the decade

- A 2019 WHO analysis found similar (but slightly lower) annual WASH-associated mortality figures of 1.4 million, with over 1 million attributed to diarrhoeal disease from lack of WASH facilities (69% of WASH-associated deaths in 2019)

- A 2023 report calculated an estimated 1 million WASH-associated deaths - a further overall reduction, however, an increasing burden in mortality under 5, with a calculated 395,000 deaths.

Over time, overall mortality and DALYs from global diseases associated with lack of WASH access have decreased, whilst sanitation coverage, reliability and robustness have increased.

Equity and Dignity

Sanitation access reflects and reinforces structural inequalities. Women and girls without safe, private toilets face increased risks of harassment and often miss school during menstruation. Furthermore, Displaced populations frequently lack adequate facilities in camps or shelters.

Economic Returns

Inadequate sanitation leads to lost productivity, school absenteeism, and higher healthcare costs. The World Bank estimates that every dollar invested in sanitation yields a return of up to five dollars in economic benefits. These savings reflect both avoided illness and time saved from safer waste disposal systems. The benefits extend to households, employers, and governments.

Climate and Crisis Resilience

Sanitation infrastructure is often vulnerable to climate-related shocks. Floods can contaminate drinking water with sewage, increasing the risk of disease. In emergencies, the absence of latrines or drainage systems contributes to the rapid spread of illness. Past cholera outbreaks in Haiti, Pakistan, and Malawi have been linked to breakdowns in sanitation following extreme weather or displacement.

Pandemic Preparedness

Sanitation helps prevent outbreaks by reducing baseline transmission and ensuring systems are not too strained to deal with incidents. In clinical and emergency settings, safe waste disposal also helps limit the further spread of disease. In urban areas, wastewater infrastructure could potentially support broad surveillance systems that can detect rising cases of known or novel diseases. These functions are increasingly relevant in the context of future pandemics.

Limitations and How Sanitation Compares

Cost and Implementation Challenges

Sanitation projects often require large capital investments and long timelines. Infrastructure must be designed, built, and maintained, often in challenging environments. Even when facilities are in place, behaviour change is not guaranteed. Some systems go unused or fall into disrepair without local engagement and ongoing support. In terms of cost-effectiveness, sanitation often ranks below other interventions. One GiveWell analysis estimated that water supply programs cost $159 per DALY averted in areas with no infrastructure, but can go as high as $2000 per DALY in areas with some existing infrastructure.

Emergency Trade-Offs

In the context of fast-moving outbreaks, sanitation alone may not reduce transmission quickly enough. Interventions like vaccination, oral rehydration therapy, or case management often have a more immediate impact. However, sanitation plays a longer-term role in reducing baseline transmission and improving the conditions under which other interventions are deployed.

Rethinking the Metrics

Sanitation may not always perform well on DALY-based rankings, but its effects extend beyond individual disease outcomes. It is linked to higher immunity resilience, can protect school and workplace environments, and supports environmental safety. In pandemic contexts, it acts as a form of risk reduction infrastructure, lowering the likelihood of uncontrolled spread and making responses more effective when outbreaks occur.

A Balanced Funding Strategy

Sanitation is best understood as a baseline layer. It may not solve every problem, but it strengthens the effectiveness of many health interventions. A tiered approach to sanitation investment can reflect differing needs across settings:

- In crisis and displacement settings, emergency latrines and hygiene access are urgent outbreak prevention tools.

- In rapidly urbanising regions, flood-resilient sewage and drainage systems are key to reducing future epidemic risk.

- In stable low-resource settings, sanitation can be embedded in schools and clinics to support long-term health, education, and equity goals.

Conclusion & Call to Action

Sanitation may not always be a top priority in global health, but without it, other efforts often fall short. It supports everything from vaccine delivery to safe childbirth, and without it, progress in both development and preparedness remains fragile.

Faster interventions often save the most lives in the moment, but long-term resilience against outbreaks and climate shocks relies on the quiet stability that sanitation provides. Sanitation is a crucial part of the infrastructure that supports health systems. It does not attract headlines, but it should never be an afterthought. A balanced global health strategy gives sanitation the place it quietly, but critically, deserves—as a linchpin of both global health and pandemic preparedness.

So what can I do? AIM (Ambitious Impact) is seeking applications to its charity entrepreneurship programs by October 5th.

Whether you have a knack for start-ups, have run non-profits, have a technology intervention idea, or simply want to try your fit and develop your skills for doing good and tackling important causes, applying is relatively quick, easy and could open up so many connections, mentors and opportunities.

Find out more about their WASH interventions here. Feel free to share this opportunity with someone who might be a good fit.