Taking ethics seriously, and enjoying the process

By kuhanj @ 2025-10-04T20:21 (+189)

Here’s a talk I gave at an EA university group organizers’ retreat recently, which I've been strongly encouraged to share on the forum. I'd like to make it clear I don't recommend everything discussed in this talk (one example in particular which hopefully will be self-evident), but I do think serious shifts in how EA community members engage with ethics and effective altruism could be quite beneficial for the world.

My first big shift (deciding to take ethics much more seriously) resulted from reading Strangers Drowning, and the second (learning to enjoy the process much more) from getting introduced to Rob Burbea's talks on meditation and ethics. I cover my favorite excerpts from both in this talk.

Part 1: Taking ethics seriously

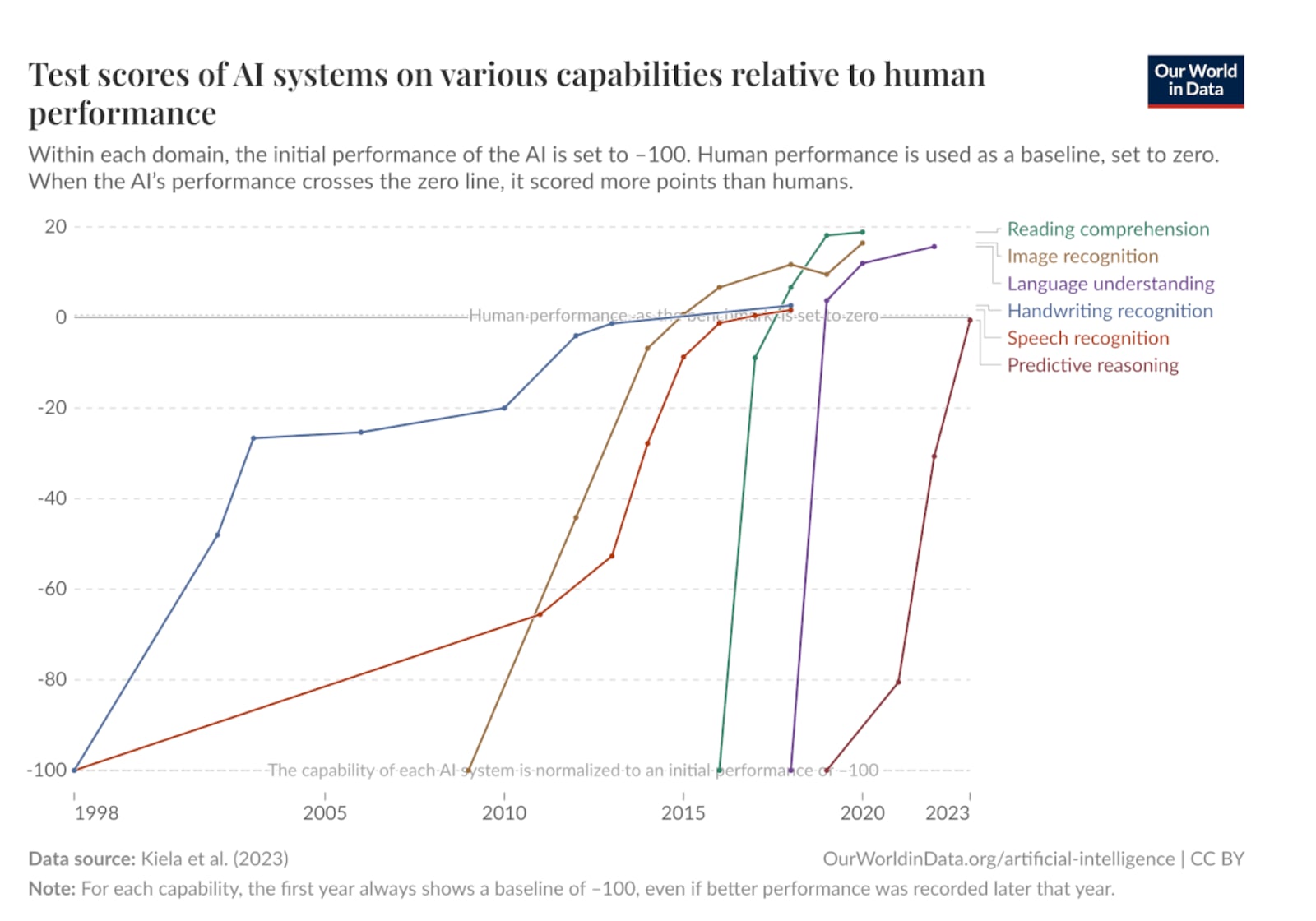

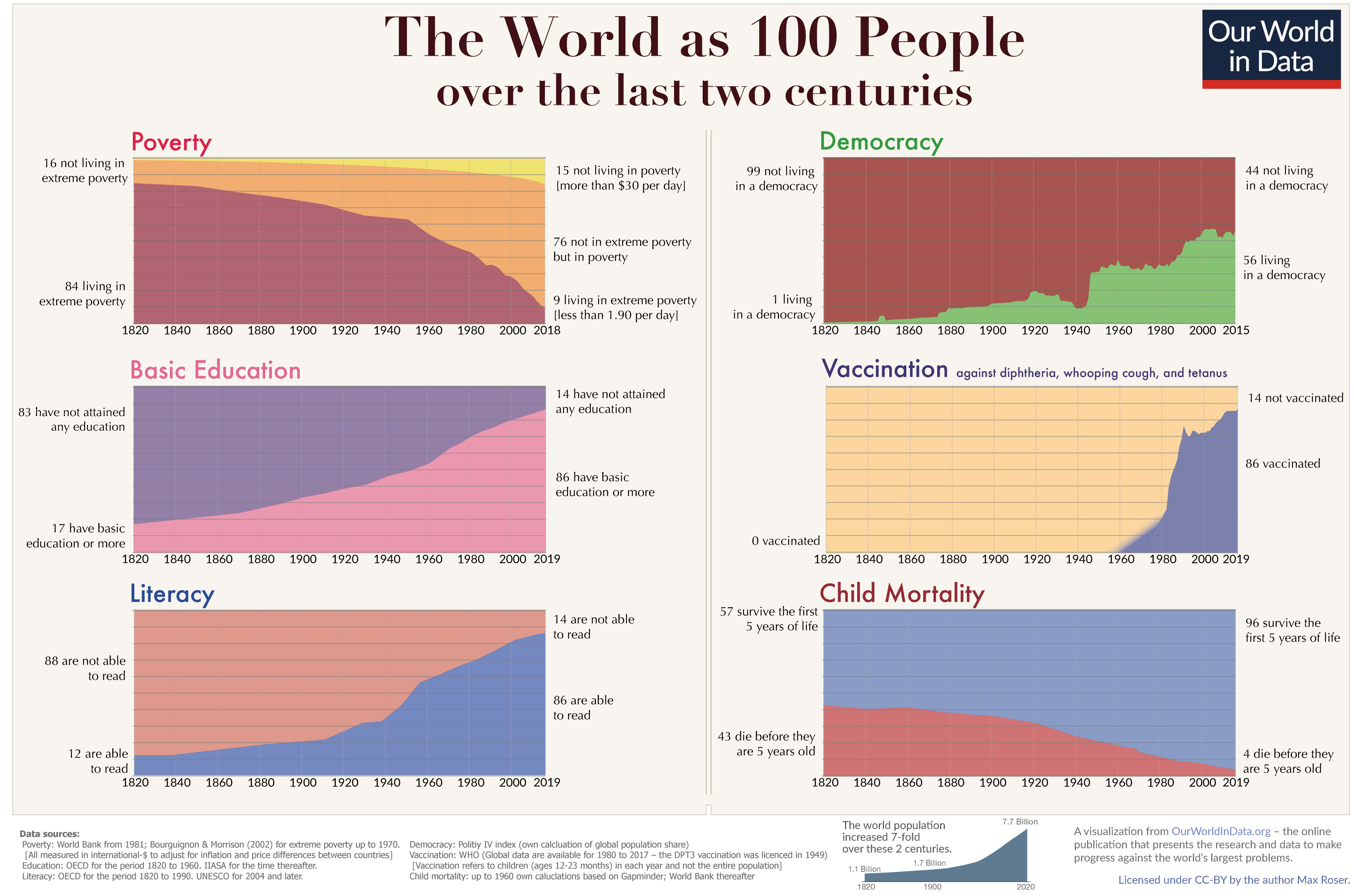

To set context for this talk, I want to go through an Our World in Data style birds-eye view of how things are trending across key issues often discussed in EA. This is to help get better intuitions for questions like “How well will the future go by default?” and “Is the world on track to eventually solve the most pressing problems?” - which can inform high-level strategy questions like “Should we generally be doing more of the same and prefer low-variance strategies, or should we consider significant changes to how we approach doing good in the world?”

***

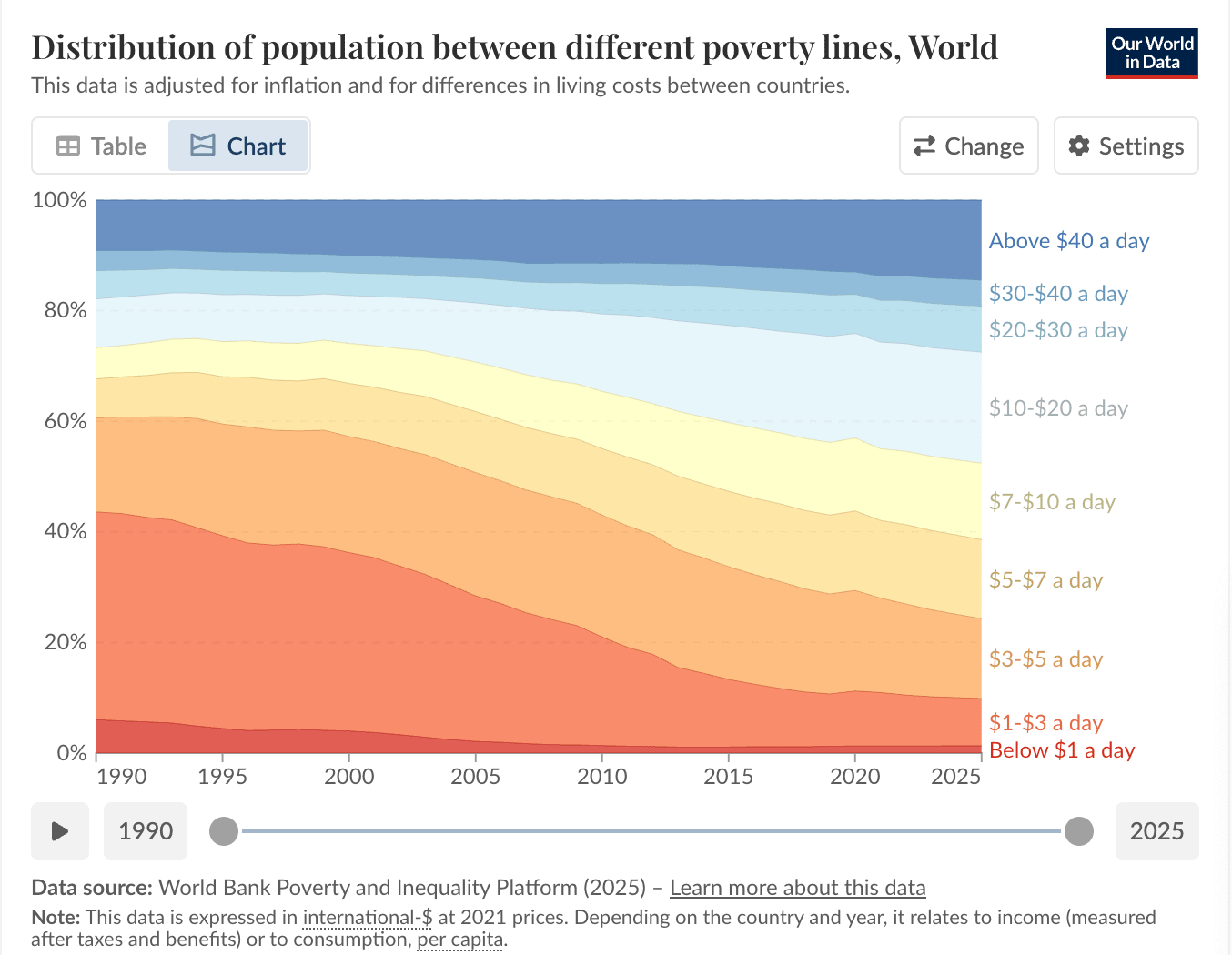

It’s often brought up that looking at many indicators, humanity has gotten much better off in the last few centuries. The percentage of people living in extreme poverty, without a basic education, who can’t read and write, who don’t live in a democracy, are unvaccinated, and who die before the age of 5 have all declined rapidly. These developments are definitely worth celebrating.

***

But from other perspectives, things don’t look so rosy.

Even still looking at just humans, the rate of decline in extreme poverty has slowed sharply in the last decade.

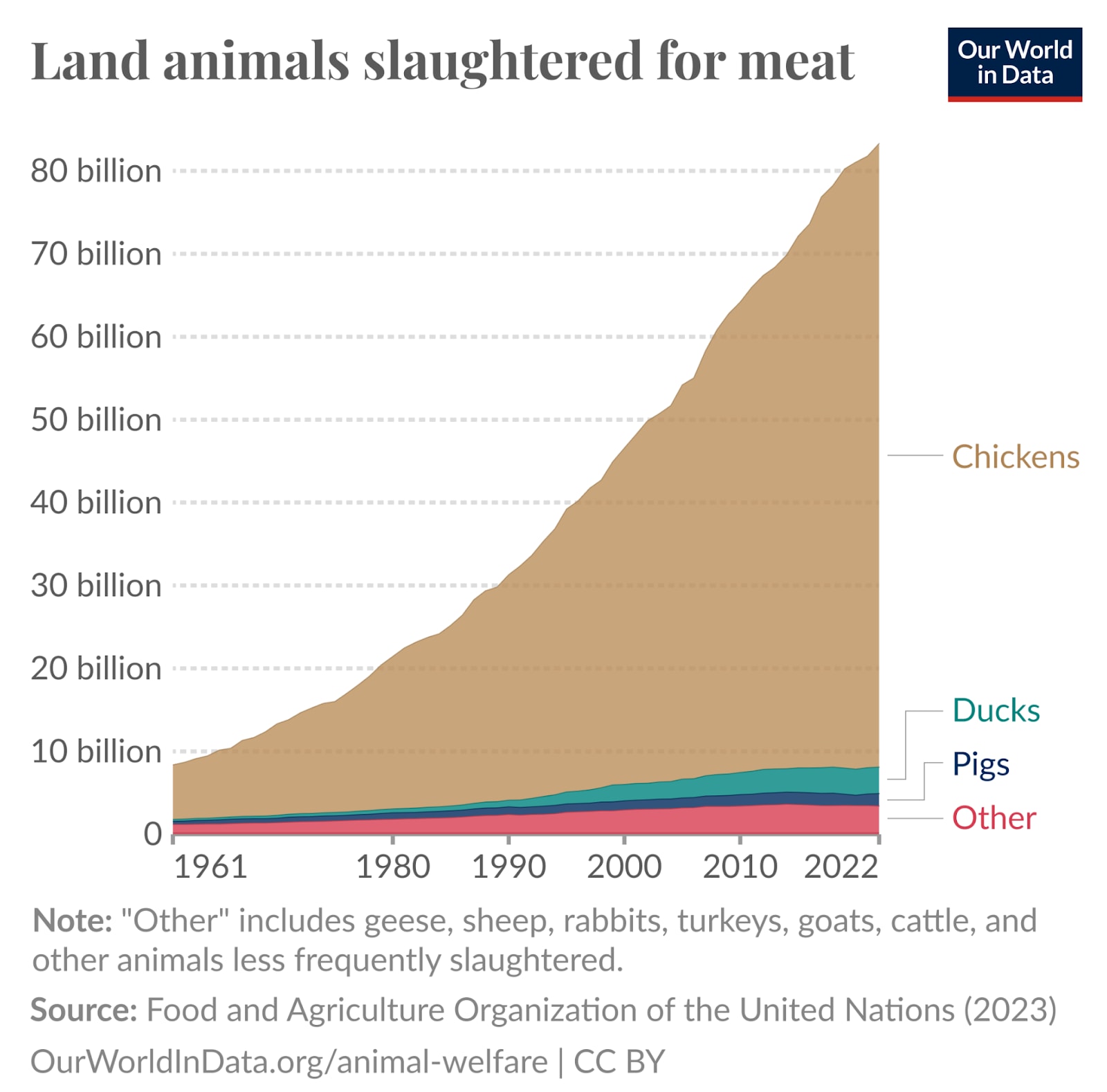

And of course when we consider non-humans, things have kept getting worse for a while, and the rate at which things have been getting worse has increased, since chickens likely suffer the most of farmed land animals.

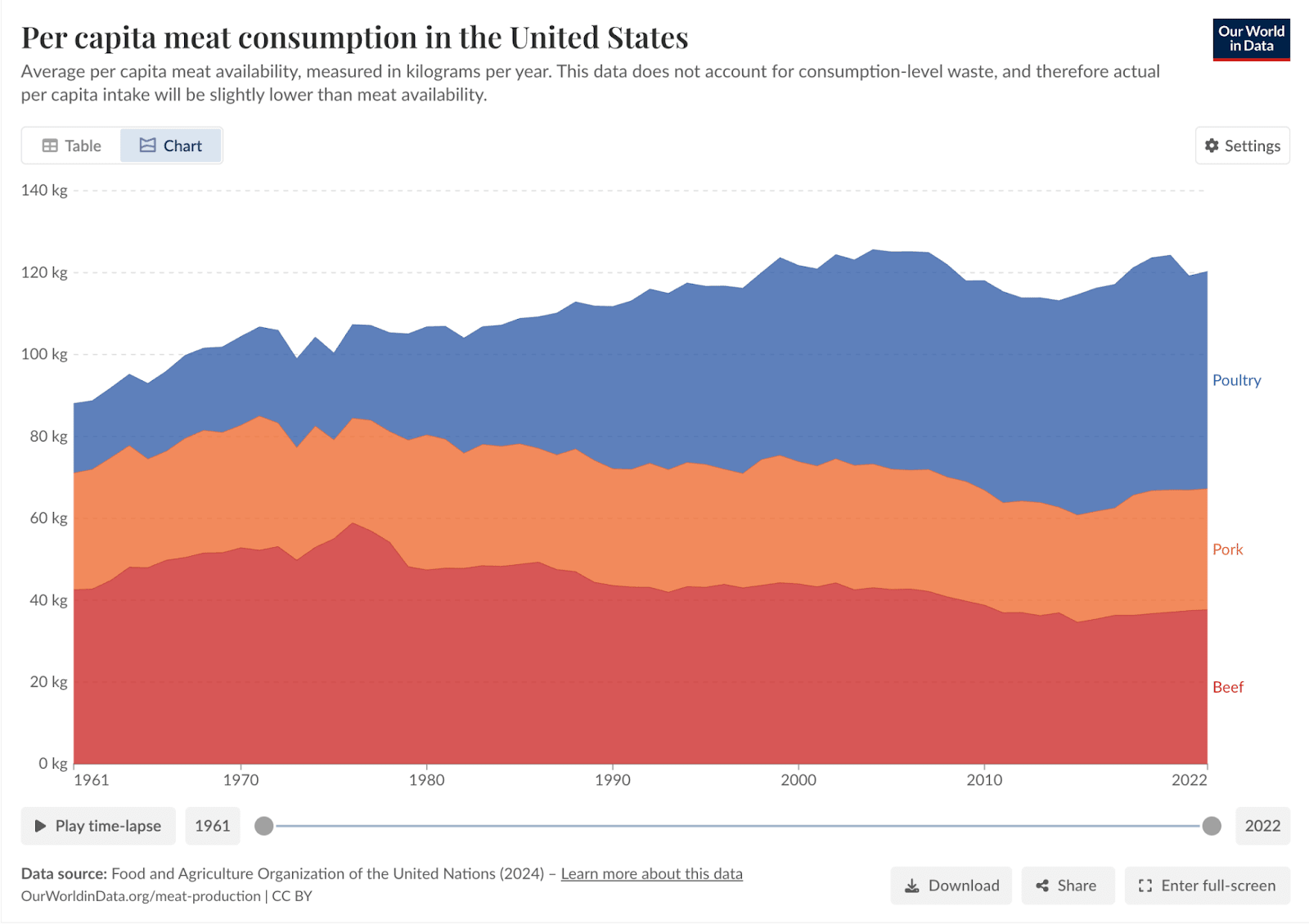

If we look at high-income countries like the US, we don’t see any signs of meat-consumption decreasing, despite increasingly tasty and cheap alternatives being developed.

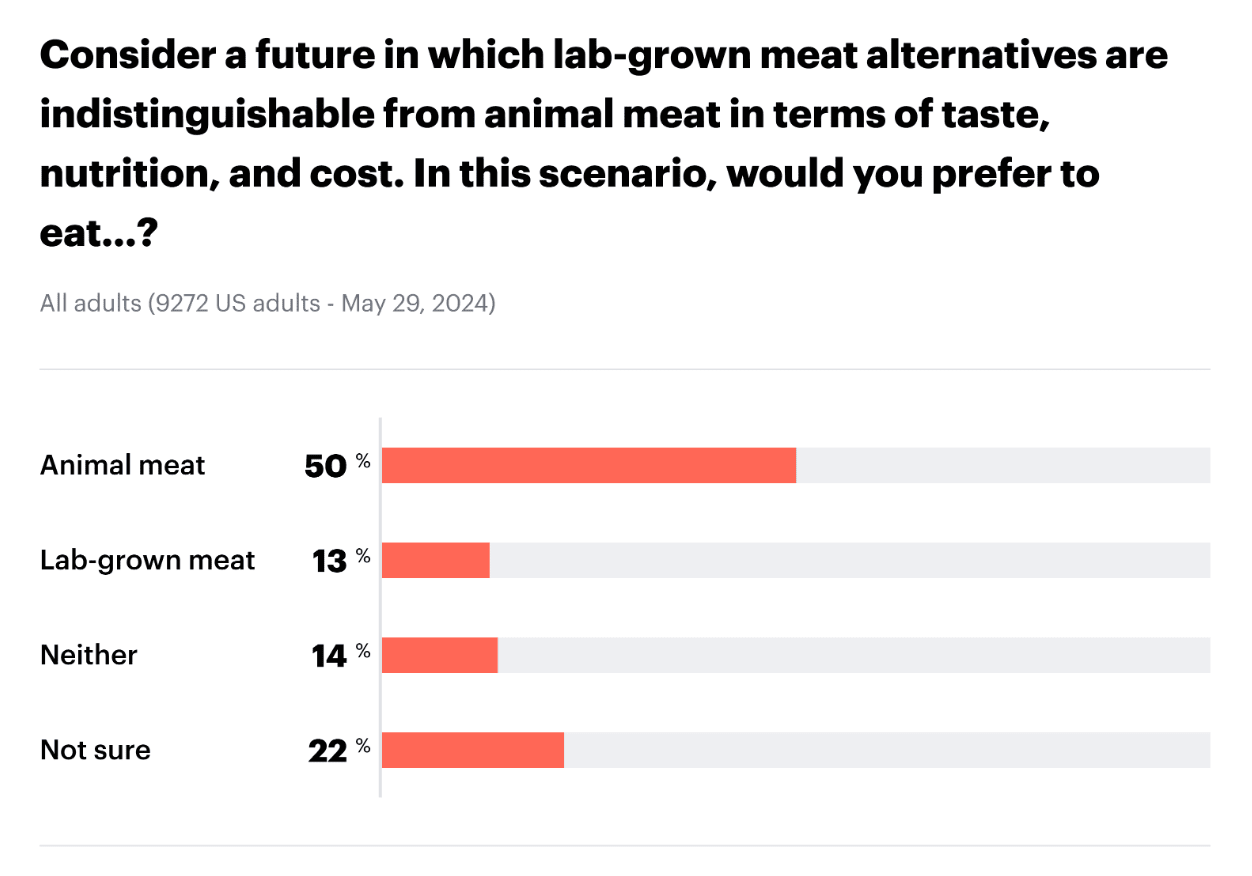

Even more discouraging is that attitudes towards cultivated meat suggest that just creating equally tasty, healthy, and cheap cruelty free alternatives might not solve most of the problem.

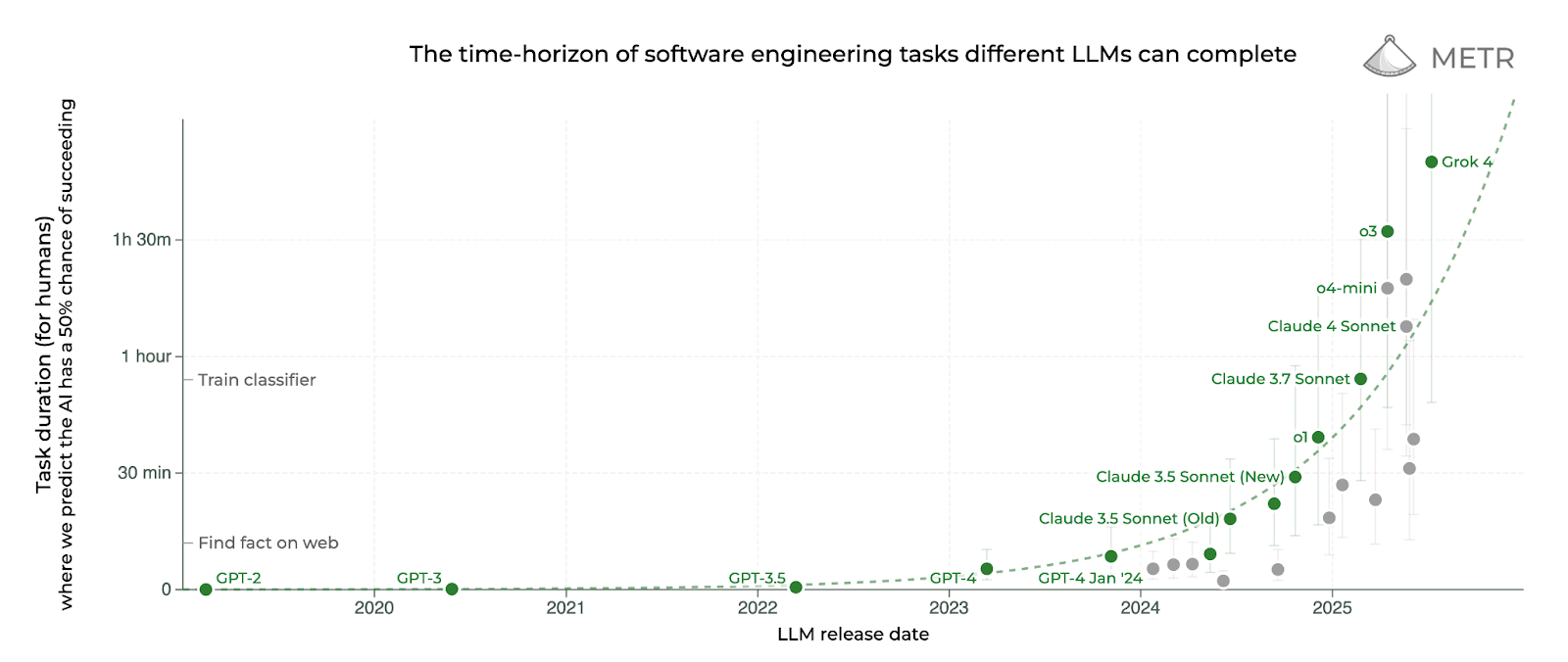

The ratio of people working on AI broadly compared to safety is estimated to be on the order of 300-1000 to 1. Though there are compelling reasons to expect things to slow down, new models seem to keep up with the trend METR has found, that the length of tasks AI systems can reliably complete as evaluated by how long it would take human experts to complete them seems to be doubling approximately every 7 months. Despite some encouraging results, progress on alignment, control, and interpretability do not seem to be keeping up.

***

Incentive shifts and moral progress

Historical moral progress might largely be explained by it being in the selfish interests of people with power (due to economic incentives, fear of violence, etc), more so than altruism. The concentration of power that is likely to come with increasingly powerful AI, and reduction in the economic value of human labor, may by default reverse the most powerful historical forces that have pushed societies towards increased democratization, liberty, and quality of life for humans. I’d recommend checking out The Intelligence Curse for more thorough discussion of these topics.

***

What is incentivized by society?

I think it’s also interesting to consider what gets incentivized by society more broadly. Who are the most powerful people in the world? Top candidates appear to be Donald Trump, Xi Jinping, and Vladimir Putin. And similarly when we look at who has the most material wealth, the top three are Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Larry Ellison.

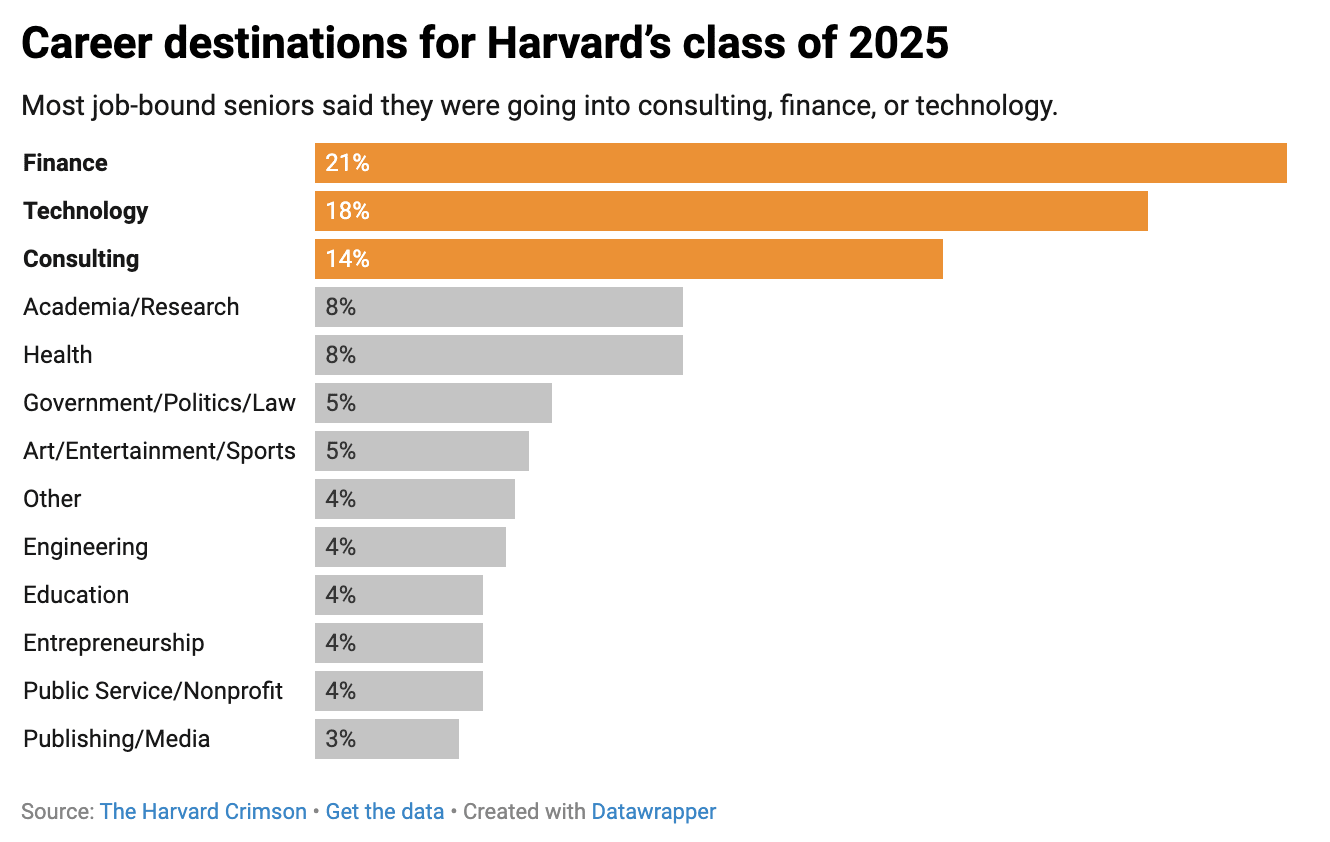

What do the world's top talent tend to do with their lives? (Shout out to fellow Stanford EA alum Justin Portela for calling this dynamic out and leveraging the attention for good).

***

So what do all the above suggest about how the future is likely to go?

I hope I’m wrong and I’m not confident, but I don’t feel very optimistic about the trajectory of humanity if we don’t at a societal level change how we relate to pleasure and pain and start prioritizing ethics and morality over quick access to dopamine. Martin Luther King Jr said in response to the Cold war "Our scientific power has outrun our spiritual power. We have guided missiles and misguided men." Marginal donations to Givewell and ACE and getting a few dozen more people to do MATS don’t feel like the kind of thing that saves us from these large trends and broken societal incentives. I think major changes are needed for the future to go well.

The most compelling candidate to me, is addressing the meta-level problem that seems to be upstream of all these specific issues - widespread apathy, a lack of compassion, and ethics and moral circle expansion not being a priority for the vast majority of people. More specifically, these not being a priority for the many people who have enough resources to very easily meet all our basic needs, and with our excess resources could make huge progress on all the problems I’ve mentioned.

***

Heroic Responsibility

Nobody thinks it’s their job to course correct society at large. Nobody gets paid to do this. But I think this is totally part of the assignment of actually doing effective altruism. I think it’s the whole point. Not just fiddling on the margin enough to feel good about ourselves. When you actually care about all sentient beings and making things better, you stare reality in all its brutality straight in the face and figure out what you’re going to do about it.

I think the world would be a much better place if EAs felt more heroic responsibility. To explain what I mean by that, I’ll share with my favorite quote from the popular fan-fiction Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality:

In this excerpt, Harry is talking to Hermione about her quest to stop bullying at Hogwarts.

"You could call it heroic responsibility, maybe," Harry Potter said. "Not like the usual sort. It means that whatever happens, no matter what, it's always your fault. Even if you tell Professor McGonagall, she's not responsible for what happens, you are. Following the school rules isn't an excuse, someone else being in charge isn't an excuse, even trying your best isn't an excuse. There just aren't any excuses, you've got to get the job done no matter what. "That's why I say you're not thinking responsibly, Hermione. Thinking that your job is done when you tell Professor McGonagall - that isn't heroine thinking. Like students being beat up is okay then, because it isn't your fault anymore. Being a heroine means your job isn't finished until you've done whatever it takes to protect the other students, permanently."

When you really care about achieving a goal, ‘I tried something’ isn’t an excuse. ‘It’s other people’s job’ isn’t an excuse.

Developing the discernment and wisdom to know what is and isn’t plausibly under our control, and what does and doesn’t actually help, are important skills. But I worry that EA culture, with its habitual focus on measurement and pragmatism and thinking on the margin, kills the kind of ambition that might actually be needed to solve the world’s most pressing problems. As things stand right now, I do not currently have faith in the EA movement’s (lack of) leadership and culture to be up to the task of actually solving the world’s most pressing problems. This isn’t reasonable to expect of anyone, but I also think our community is missing out on a ton of potential impact given the altruism, talent and resources in our community. I sense we could have accomplished much more by now.

I worry our culture has overly heightened sensitivity to downside risk, and insufficient sensitivity to lost potential upside. We are overly pre-occupied with mistakes in execution, and insufficiently pre-occupied with lost opportunities and mistakes of omission. Most importantly, EA culture can feel too unambitious and slow, lacking the pants-on-fire urgency, heroic responsibility, and deep care I think are needed to meet this moment. I don’t know how much the FTX collapse is responsible for our current culture. They did cause unbelievable damage, acting extremely unethically and unilaterally and recklessly in destructive ways. But they did have this world-scale ambition, and urgency, and proclivity to actually make things happen in the world, that I think central EA orgs and the broader EA community sorely lack in light of the problems we’re hoping to solve.

There are of course crucial lessons to internalize about the perils of optimization and naive utilitarianism/EV maximization without hard constraints. I am very worried that the importance of non-violence has been insufficiently emphasized in society in light of high-profile political violence. But I worry that we’ve thrown out the baby with the bathwater as a community in our response to FTX.

It often feels like there’s a mismatch between the kinds of problems we look at tackling, and the scale of solutions we consider. The requisite ambition, thoughtfulness, and hunger to really transform the world for the better, and the urgency to avert these tragedies as quickly and effectively as possible - I think that these may need to come from organizers like you, to influence the EA community, and world more broadly.

I think the first step is to cultivate moral seriousness.

***

Excerpts from Strangers drowning

A few years ago, I read a book called Strangers Drowning, a series of profiles on what the author Larissa MacFarquhar describes as “extreme do-gooders”. It’s been the most life-changing book I’ve read. Two quotes really struck a chord with me, and feel particularly salient now.

"There is one circumstance in which the extremity of do-gooders looks normal, and that is war. In wartime — or in a crisis so devastating that it resembles war, such as an earthquake or a hurricane — duty expands far beyond its peacetime boundaries… In wartime, the line between family and strangers grows faint, as the duty to one’s own enlarges to encompass all the people who are on the same side. It’s usually assumed that the reason do-gooders are so rare is that it’s human nature to care only for your own. There’s some truth to this, of course. But it’s also true that many people care only for their own because they believe it’s human nature to do so. When expectations change, as they do in wartime, behavior changes, too.

In war, what in ordinary times would be thought weirdly zealous becomes expected… People respond to this new moral regime in different ways: some suffer under the tension of moral extremity and long for the forgiving looseness of ordinary life; others feel it was the time when they were most vividly alive, in comparison with which the rest of life seems dull and lacking purpose.

In peacetime, selflessness can seem soft — a matter of too much empathy and too little self-respect. In war, selflessness looks like valor. In peacetime, a person who ignores all obligations, who isn’t civilized, who does exactly as he pleases — an artist who abandons duty for his art; even a criminal — can seem glamorous because he’s amoral and free. But in wartime, duty takes on the glamour of freedom, because duty becomes more exciting than ordinary liberty…

This is the difference between do-gooders and ordinary people: for do-gooders, it is always wartime. They always feel themselves responsible for strangers — they always feel that strangers, like compatriots in war, are their own people. They know that there are always those as urgently in need as the victims of battle, and they consider themselves conscripted by duty."

And the second:

“What do-gooders lack is not happiness but innocence. They lack that happy blindness that allows most people, most of the time, to shut their minds to what is unbearable. Do-gooders have forced themselves to know, and keep on knowing, that everything they do affects other people, and that sometimes (though not always) their joy is purchased with other people's joy.”

And, remembering that, they open themselves to a sense of unlimited, crushing responsibility.”

They can no longer continue to live ignoring the unbearable—they feel an intense urge to dedicate their lives to helping others.

***

Opening our eyes to what is unbearable

To know, and keep on knowing, is exhausting. I'm going to list some facts many of us are familiar with. But really holding space in our minds and in our hearts for what they imply — for the actual scale of the suffering, and unrealized joy, and injustice in our world — can be overwhelming. But it is important to be reminded from time to time, to keep things in perspective.

About one in 10 people live off less than $3 USD a day, many of whom have or are children whose lives are cut tragically short by cheaply preventable diseases.

There are over 70 billion land animals, and over one trillion aquatic animals severely mistreated and killed for food each year.

For my fellow scope-sensitive nerds who are moved by large numbers, quoting from the paper astronomical waste: the potential for approximately 10^38 human lives is lost every century that colonization of our local supercluster is delayed; or equivalently, about 10^29 potential human lives per second. However, the lesson is not that we ought to maximize the pace of technological development, but rather that we ought to maximize its safety, i.e. the probability that safe colonization will eventually occur.

It’s unfortunately easy for us to gloss over numbers, and not really grapple with them. So I’d like to ground these numbers by reminding us of what’s happening in the real world. I tried to use a video that I think is challenging but manageable, so there’s no blood or gore in this video, but you can close your eyes if this is too upsetting. Notice what comes up as you watch it. And if you’re up for it, if you notice an instinct to flinch away from an aversive feeling, try resisting that urge and stay with the feeling for a bit and notice what happens.

[Factory farming 45 second montage]

Videos like this put things in perspective, and remind me how much taking ethics seriously matters. What could possibly matter more? All my personal pre-occupations are just so clearly a rounding error in comparison to the magnitude of suffering and wellbeing that can be influenced by my actions.

There are so many sentient beings who can’t advocate for themselves at all. Animals and future sentience have a special place in my heart for this reason.

It is truly heartbreaking when you open your eyes and heart to what is unbearable. But at the same time, obviously crying and feeling despair on its own doesn’t help anyone. And there are so many tragedies going on all the time, and we can’t solve all of them. So what do we do? The natural instinct is to shut our eyes and close off our hearts and forget. But this usually means apathy and inaction.

"All that is needed for the forces of evil to prevail is for enough good men and women to do nothing."

***

There are so many causes worthy of the full dedication of our lives. So many tragedies to avert. So many opportunities to create more joy and love and peace, and everything else that makes life so precious.

If we want to help as much as we can, we shouldn’t just take the effects of our actions at face value—we should compare our actions to everything else we could have done with our limited time, money, and attention, and pick the very best option. We’re always making trade-offs, whether they’re intentional or not, so it’s best to be cognizant of them, and make them in a way we endorse.

***

Increasing effectiveness vs. increasing altruism

I think the EA community often does a good job of shining a light on these different tradeoffs, and emphasizes the importance of prioritization, rigorous epistemics and analysis of ethical considerations, and looking into data and evidence when available.

But there is something missing around our emotional orientation to ethics that may be of similar, I’d argue even greater importance.

Too often in EA, the extent of our altruism is taken as a given, and the emphasis placed on taking this existing altruism and making it more effective. Taking the resources we already want to allocate impartially for the benefit of others; and figuring out how to do so in a way that is sensitive to effectiveness, and scope, and the moral patienthood of all beings worthy of care.

I rarely see the community discuss or emphasize how to increase our altruism, and our capacity for altruism, both on an individual and societal level. But I think this might be much more important to emphasize than effectiveness. One reason is that as our altruism increases, our desire to be effective with our altruism naturally increases as well. When you care more deeply about all sentient beings, trade-offs and opportunity cost become more salient. I don’t see as much of a similar positive feedback loop in the other direction - increased effectiveness leading to increased altruism. Being more effective in one’s altruism can inspire conviction about tractability (and thereby increase altruism), but emphasizing effectiveness on its own can feel less intuitive and engaging than what we naturally feel drawn to, and often feel demotivating, dampening our altruistic impulses.

We encourage people to donate 10% of their income to effective causes, since 10% is a familiar number from certain religious traditions and doesn’t seem too daunting. But we don’t really ask, how could we make people really want to go from 10% to 90%. Or how to fix the widespread problem that causes 10% to be a non-starter for the vast majority of the most wealthy people in the history of humanity - many of which are our family members, friends, colleagues, classmates.

***

Cognitive dissonance

There is a cognitive dissonance that I think we all feel on some level subconsciously when discussing these gigantic global and even lightcone-scale issues and unbelievable amounts of suffering, but not really fully devoting ourselves to fixing them, and acting in accordance with our beliefs. Maybe consciously we can talk about the scale of factory farming combined with the likely moral patienthood of non-human animals, or the sheer potential scale or the long-term future and acknowledge them purely on an intellectual level. But I think our subconscious can sense something is off when we talk about these huge if true ideas, but don’t really take their implications with the gravitas they deserve and act accordingly - as if we don’t really believe what we’re saying deep down, or are maybe too afraid to take these beliefs seriously because of their implications.

The property of the people profiled in Strangers Drowning I found most admirable is what I’d call persistent moral courage, and the extent of their dedication to improving the world over the course of their lives. I’ll share a few other examples of moral courage that inspire me.

***

Paragons of moral courage

Harriet Tubman repeatedly returned to the South to lead enslaved people to freedom through the Underground Railroad, despite enormous personal risk and bounties on her head.

Oskar Schindler saving over 1,000 Jews during the Holocaust by employing them in his factories and bribing Nazi officials, spending his entire fortune in the process.

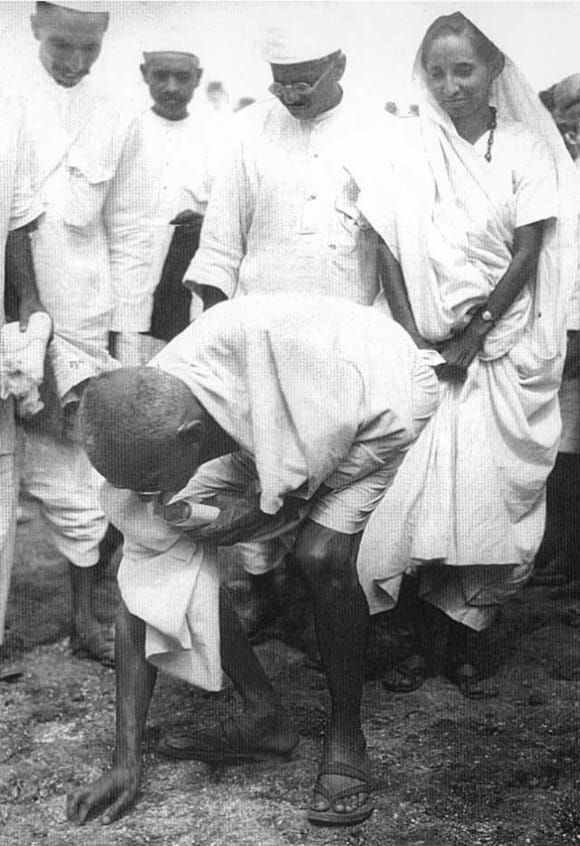

Mahatma Gandhi led a 24 day, 240-mile walk to Dharasana salt works at the Arabian Sea as part of the salt march, picking up a handful of salt to violate Britain’s monopoly on salt production, since Indians were required to buy heavily taxed salt from the British when they colonized India. The most famous and well-documented violence occurred about two months after Gandhi’s initial protest, but American journalist Webb Miller’s famous eyewitness account of the demonstration was published worldwide and included this description: “"Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off the blows. They went down like ten-pins... The waiting crowd of watchers groaned and sucked in their breaths in sympathetic pain at every blow." It had an enormous impact on international opinion about British colonization. From 1966 to 1999, nonviolent civic resistance is thought to have played a critical role in fifty of sixty-seven transitions away from authoritarianism.

The last example is the most graphic, and I was debating whether or not to include it since I think it’s way too extreme and don’t intend to encourage this behavior or suggest that it happens in EA world because it totally doesn’t and almost definitely isn’t the most effective way to do the most good in nearly all cases. But it demonstrates a really powerful point about what the human mind is capable of with sufficient training that most people haven’t really internalized the implications of.

***

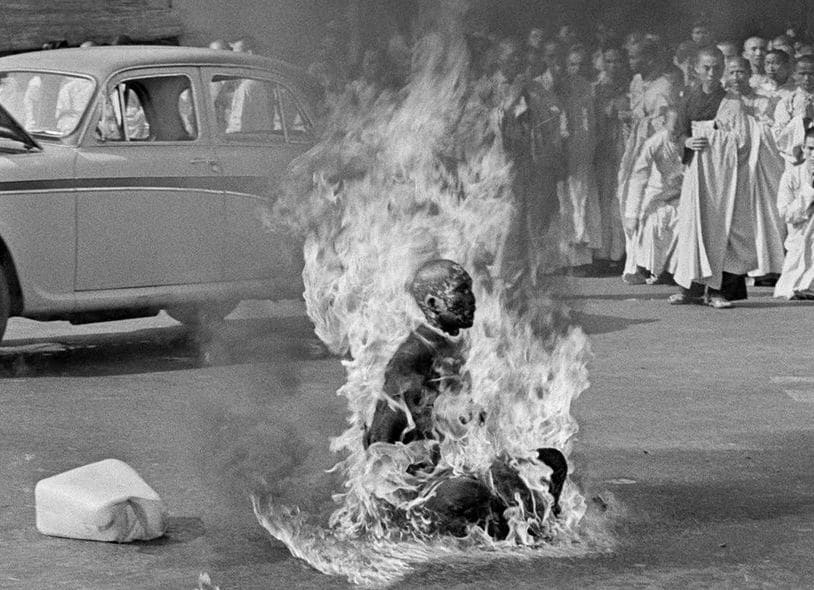

The monk who set himself on fire to protect Buddhism, and didn’t flinch

These photos were taken in Saigon in 1963. A Buddhist monk named Thích Quảng Đức was protesting the persecution of Buddhists under the U.S. backed South Vietnamese Government, which was led by a devout Catholic Ngô Đình Diệm. Beyond the unbelievable moral courage it takes to set oneself on fire, another aspect of his demonstration stood out. He purportedly did not flinch or react from the moment he set himself on fire until he went unconscious.

Thích Quảng Đức’s control over his focus and non-reactivity was a palpable manifestation of Buddhism at work, and it woke South Vietnam (and the wider world) up to what a valuable philosophy and religion that Ngô Đình Diệm was destroying.

Thich Nhat Hanh, another well-known Vietnamese monk who popularized Buddhism in America, explained the actions of his colleague in a letter to Martin Luther King Jr:

The self-burning of Vietnamese Buddhist monks in 1963 is somehow difficult for the Western Christian conscience to understand. The Press spoke then of suicide, but in essence, it is not. It is not even a protest. What the monks said in the letters they left before burning themselves aimed only at alarming, at moving the hearts of the oppressors and at calling the attention of the world to the suffering endured then by the Vietnamese. To burn oneself by fire is to prove that what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with the utmost of courage, frankness, determination and sincerity. During the ceremony of ordination, as practiced in the Mahayana tradition, the monk-candidate is required to burn one, or more, small spots on his body in taking the vow to live the life of a bodhisattva, to attain enlightenment and to devote his life to the salvation of all beings. One can, of course, say these things while sitting in a comfortable armchair; but when the words are uttered while kneeling before the community and experiencing this kind of pain, they will express all the seriousness of one's heart and mind, and carry much greater weight.

A person who is ready to engage in peaceful self-immolation and who is called to it and chooses it becomes, quite literally, a torch. This torch shines a light on suffering in the world that many people want to turn away from. John F. Kennedy himself said of this act, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.”

The protest (and Browne’s famous photograph of it) was thought to have an enormous impact. The White House began to believe Diệm was losing control, and later that year backed his assassination.

***

What we are willing to do

I am not in any way advocating for self-immolation. I think for basically every problem, there are more effective ways to actually make progress. Even if there weren’t, I wouldn’t want to push anyone to such extremes. But I can’t help but wonder what it takes to develop the moral courage and control over one’s nervous system and mind, to set oneself on fire for a cause they believe in deeply, and not even flinch. Equipped with these powers, what can’t you do?

Working long hours and on weekends, donating most of my money or taking a large pay cut to do more impactful work, changing my diet, overcoming social anxiety and communicating what’s important publicly and having tough conversations, and many other things that seem difficult but compelling on ethical grounds, are a walk in the park in comparison.

When I reflect on what causes me to take actions I don’t endorse, it largely boils down to instinctual avoidance of pain and chasing of pleasure. It doesn’t happen over night, but it’s possible to train ourselves so these instinctive impulses bother us less and get weaker over time, and can be replaced by more intentional responses, and increasingly higher baseline wellbeing that gives us the affordance to productively, sustainably engage with suffering in the world.

So what moves these paragons of moral courage to act the way they do, and what sets them apart? I think it’s largely consistent, moment to moment clarity on and conviction in their priorities.

***

What do I most deeply want to honor in this life?

Rob Burbea teaches about meditation and ethics, and has been hugely influential in how I orient to doing good. I’m going to share several of my favorite excerpts from his talks, this first one from a talk about renouncing sensual pleasures to access deeper joy and meaning:

What is my life about? What’s pulling me? What is really pulling me? So is it that really, in my life, for the most part, what I deeply care about, my aspirations, my deep principles are pulling me? Or is it pleasure and avoidance of pain that’s pulling me? Sometimes you can see as people grow over the decades, you can see how characters get shaped over the years. And this is an important factor in what shapes character. How much, as human beings, are we living true to what we really, really believe in deeply and care about? And how much are we being pulled off that, not really settling on that, not really yoking ourselves to that? We’re being pulled off that because of pleasure, and just being pulled into chasing something. And you can see: someone who’s lived close, rooted in their truth, the sense of that person – there’s a power there. I don’t mean power over other people. I mean an internal power. There’s a strength. There’s an integrity. And in the opposite, that those qualities are not there. There’s often a kind of sense of vagueness or scatteredness or a little bit of weakness, fearfulness.

And none of this is to judge. It’s really not about that. It’s rather about – can we hear it not as something to judge, but rather, what do I want to honour? What do I most deeply want to honour? Which part of my being do I most deeply want to honour in this life?

***

Moral Courage and defending EA

A related topic I want to touch on is defending effective altruism. Matt Reardon has a great blog post EA adjacency as FTX trauma, that discusses how the community’s response to FTX criticism is likely largely driven by instinctive aversion to negative emotions, rather than dispassionate examination of what response would be ideal for the world.

It can often seem beneficial when only considering one’s own career and impact and reputation to distance themself from the EA label and community in light of the FTX collapse and negative press we’ve received. But there is a clear tragedy of the commons dynamic going on. EA ideas have brought so many brilliant caring people together, and I know so many people have immensely benefited from the ideas, community, and professional opportunities that were possible thanks to the banner of effective altruism and the power of its purpose.

If we aren’t willing to put ourselves out there and fight for EA ideas and values and community members, and most importantly for those who can’t advocate for themselves like animals and future biological and digital sentience, who will?

When we hide our connection to EA with mental gymnastics that don’t pass the sniff-test, others think we’re doing so because we actually have something to hide, something to be ashamed of. What could possibly be less worthy of shame than a sincere desire to help others effectively?

If some people can set themselves on fire to defend what they believe in, surely we can develop the courage to speak up publicly, and stand up to haters on the internet. The more upstanding, clearly well-intentioned and cooperative people who loudly and proudly associate ourselves and the good we do with EA, the easier it becomes for everyone else to do so. The more likely it is that others find the immense value in the ideas and ideals that bring us together, which we know are of incredible significance.

In my (for what it’s worth, very secular) opinion, both Buddhism and EA have produced a treasure trove of insights with huge implications for increasing wellbeing and reducing suffering in the world. It is a monumental tragedy that these insights have such limited reach - one that is vital to fix.

***

Acknowledging opportunity cost and grappling with guilt

Initially, heroic responsibility, and radically embracing all the ways in which the world could be better as your responsibility, as your mandate, can be very difficult emotionally.

When I first learned about EA, I was often wracked with guilt about not being a good enough person. The guilt was sometimes so severe that I would sometimes compare myself to a serial killer because of all the lives I could have saved if I thought more carefully and worked harder, and if I were less impulsive,, more disciplined, more courageous.

I would hear the people around me give unsatisfying excuses to the implications of the drowning child argument, but they were all obviously bullshit. It is just straightforwardly true that the opportunity cost of our time and money, if we genuinely care about all other sentient beings, is unimaginably high. So many lives, current and future; human, non-human, and digital; could be saved and improved. So much joy, and so much suffering are at stake with every decision we make. Pretending otherwise is an affront to our agency, and to the moral worth of the countless beings we could help.

It’s natural and common to reflexively flinch away from uncomfortable ethical considerations, in the same way we’d flinch when we touch a hot stove and burn ourselves. But flinching away from some problems doesn’t make them go away.

Instead of avoidance, how can we embrace the world’s suffering and its greatest problems, and our role in fixing these, effectively, sustainably, and cheerfully - and in a way that gets others excited about joining us on this quest?

Part 2: Enjoying the process

Celebrating what’s really beautiful - what our hearts care about

I have been reflecting recently on the effectiveness of using positive vs. negative emotions to motivate behavior change. I often ask myself: How could I do more good? How could I be more productive? What mistakes am I making? What would a more courageous, smarter, ethical, virtuous version of me do differently?

Until I started engaging with Rob Burbea’s content and meditating, it was rare that I’d take a step back and appreciate how wonderful it is to care about helping others. Nor did I celebrate being part of a community that cares so much that we want to do so as effectively as we can. A community that is willing to rigorously question our intuitions, motivated reasoning, and biases to help others more effectively, and do what is right, even when it’s hard.

This excerpt from a talk about ending the inner critic deeply moved me, and has meaningfully shifted my emotional orientation to doing good, and importantly, also to the other unimportant junk my brain often preoccupies itself with.

Excerpt from “Ending the Inner Critic”:

“So what would it be to really sit in, or incline the mind, incline the awareness, to dwell in a recollection, an acknowledgment, an admittance of the beautiful qualities within us, that which is lovely within us? It’s interesting saying this because, again, you think, “Oh, that’s going to be completely ineffectual,” but also a person might think, “Wouldn’t that be egoic? Wouldn’t that be some kind of ego trip?” It won’t be at all. Funnily enough, the inner critic is actually a kind of ego trip. It’s just turned upside down. The ego is actually massive when the inner critic is there. The self-sense is massive. It’s way overblown, but it’s all negative.

I have to be careful what qualities I acknowledge and what qualities I choose to celebrate and dwell in acknowledgment of. The cultural pressure will be for worldly qualities – what kind of car do you drive, what do you do for a living, what’s your social status and all that. And again, it can feel like, “I’m not influenced by all that. I don’t buy into all that.” But we live in that culture where that is what determines people’s opinions of each other, oftentimes, in terms of celebrities and all that. What would it be to respect ourselves for the right things, for the important things? So for our ethics, for instance. You know, you don’t open a newspaper and see a whole list of celebrities who get celebrated for their ethics or their care of ethics. It just doesn’t register in most people’s consciousness as something that’s worthy of bowing, worthy of devotion, worthy of celebrating. Or not even ethics, but my intention to live ethically, or inquiring into what it means to live ethically, to explore that. Just that those intentions come up in me is something extraordinarily beautiful – especially these days with globalization, very complex ethical issues, that I care about trying to navigate through that in some way. It won’t put you in the newspaper, it won’t make you famous, it won’t make you rich. But there is so much more beauty in that than any of that other junk that we can very easily be kind of brainwashed into believing that this is what we should be respected for.

The intention to cultivate qualities of mind like kindness, like goodness, like concentration, all of that. These are beautiful, [...] noble intentions. Something so worth celebrating. Very easily we can lose touch or [...] not even fully be aware of what it is that we care about most.

Sometimes, the things that don’t sound like a big deal are actually way more a big deal than they seem. There’s so much potential for a kind of unshakeability here. We’re rooted in what we care about the most. If we’re going to play the game of respecting ourselves and kind of judging how much respect we’re worth – which is a very dangerous game to play anyway – if we’re going to play it, at least let it be for the right things, for the things that are really beautiful and really important, that our hearts care about.”

***

I’d like everyone to take a minute to yourself, in whatever way feels genuine, to appreciate how beautiful your intention to do good effectively is, to celebrate all the good you’ve done already, and to feel gratitude to have the privilege and ability to dedicate some of your resources to help others.

***

The quality I find most valuable to cultivate, most importantly for my impact, but also for my wellbeing, is generosity. Here are three of my favorite excerpts from Rob about cultivating generosity:

Sometimes when we’re looking at a beautiful, positive quality like generosity, it’s helpful to look at the ways that we find ourselves not being generous fully, being stingy. And that doesn’t just apply to money. Am I limiting my generosity to others, and even to myself, in terms of my kindness? Do I limit the expression of my kindness? Do I limit the expression of my appreciation to myself and to others? Am I limiting my wholeheartedness, in life and in meditation? Am I holding something back – something of my energy, something of my being? Do I hold it back? Am I limiting my generosity in terms of attentiveness, of energy? Am I a little bit stingy with my intensity as a human being? You know, sometimes we just keep the radio on, or the TV is on in the background, it’s kind of draining our intensity. It doesn’t let an intensity of aliveness, of attention build. It doesn’t let that flame build to become strong.

And another excerpt:

What happens as we practise generosity, and especially, as we stretch it? Something happens to our feeling of abundance. It’s almost like when we’re generous, we’re acting as if there is abundance, and that brings the perception of abundance. Like all things, our sense of resource is a dependent arising, dependent on the heart. Very dependent also on how we see ourselves, at a gross level and also at a very subtle level. That will affect our sense of abundance and resource. Our inner wealth affects our sense of abundance. Do we have a sense of inner resource? And that’s why, in meditation, I put so much emphasis on just gently encouraging that well-being, because that will deepen. And we talk about loving kindness, and and compassion and other qualities, those become our store of inner resources. A sense of abundance is also dependent on less sense of self. The less the sense of self, the quieter the self, the more the sense of abundance. The quieter the fear, the less entanglement in fear, the more the sense of abundance. What’s the implication of that? One of the implications is, when I feel like I don’t have enough, give. Give when you feel you don’t have enough. When I feel like I’m not getting enough money, when I feel like I’m not getting enough love, give.

And it’s not about “If I give, then I’ll get. Someone else will give to me,” although that may well be true. But it’s what I said before: when I give, the heart opens, and the perception of the world changes. And that’s why we need to practise really stretching our edges with generosity, because if we only give a little bit, we won’t see so much of that shift of perception. The very perception of the world changes when we stretch ourselves, when we practise a radical generosity. Generosity shapes our perception of things at every level. And one might ask, then: what kind of world do I want to live in? I see when I’m not generous, when I’m bound by my fear, when I’m constricted, when I’m a little bit tight, the world appears a certain way. When I practise generosity, when I unbind from that, the world starts looking different. And the more I practise, the more the degree of generosity, the more the shift in the sense of self and the sense of the world. The world appears very different. The world at times can appear solid and impinging and threatening and dark almost. But it can also appear radiant, beautiful, filled, permeated with love, light, spaciousness. Which is the real world?

***

Enjoying effective altruism

I think it’s so, so important to love and enjoy engaging in effective altruism - both for the sake of the world, and for ourselves. I believe very strongly that it is much better for the world if my engagement with EA primarily comes from a place of excitement, and kindness, and compassion, and internal abundance. From recognizing and feeling gratitude that I have more joy and love and peace and stability than I need, and from trusting that I can cultivate these both internally and with external support as needed. And that because of this, I would rather share my excess resources than spend them on myself. Cultivating the sense that life has given me an enormous, delicious cake, knowing I only need a small piece to be full myself. And that genuinely, deep down, I'd feel better sharing the rest of it with others. And this all comes from a deep conviction that trying our best to do as much good as I can is really beautiful, and really matters. That nothing could possibly matter more.

To me, practicing effective altruism means repeatedly cultivating and stretching my generosity and compassion - towards others and myself - with my time, my money, my attention, my energy, my intentions, my thoughts, and my actions.

It is so valuable to cultivate generosity, compassion, courage, humility, humor, dedication, discernment, forgiveness, joy, equanimity, creativity, focus, open-mindedness, skepticism, truth-seeking, agency, earnestness, intensity, optimism and hope that the future can be better, and all the other qualities you wish to see more of in your group members, and in the world more broadly.

Repeatedly, intentionally cultivating these positive qualities inclines the mind towards them, and increasingly make them our default behavior.

It’s useful to cultivate these positive qualities not just for your own wellbeing and impact, but to set a positive example for both existing and potential group members. How excited do you expect students to be to join your group if you and other organizers seem stressed out of your minds, wracked with guilt, or maybe organizing begrudgingly, out of a sense of obligation, and maybe half-assing it?

In comparison, if you and other organizers are filled with a deep sense of purpose and moral seriousness, and at the same time are incredibly kind, and filled with joy and energy and humor, and have deep friendship and camaraderie with others dedicating whichever resources they’re excited to dedicate to make the world a better place – how appealing does that group sound?

***

Training our minds to cultivate the qualities we endorse

I can say from personal experience that it is possible to train your mind to an astonishing degree to incline itself towards the positive qualities you wish to see in yourself and others. It is possible to see large, positive changes, sometimes quite quickly, through certain types of loving kindness/jhana meditation, emotional processing, conscious reflection, and other activities. I find that meditation is for my subconscious and System 1, what EA is for my intellect and System 2. I’m happy to chat more with anyone interested in learning more. I’d also strongly recommend exploring content from Rob Burbea, the author of the excerpts I’ve been sharing.

Here is the opening quotes from his book Seeing that Frees:

We will find that as insight into these teachings deepens, we become, as a matter of course, more easily moved to concern for the world, and more sensitive to ethics and the consequences of our actions. Opening to emptiness [by which he means their lack of inherent nature independent of mental perception and fabrication] should definitely not lead to a lack of care, to indifference, cold aloofness, or a closing of the heart.

If I find that my practice is somehow making me less compassionate, less generous, less caring about ethics, then something is wrong in my understanding or at the very least out of balance in my approach, and I need to modify how I am practising.

Generally speaking, and although it may at first seem paradoxical, as we travel this meditative journey into emptiness we find that the more we taste the voidness of all things, the more loving-kindness, compassion, generosity, and deep care for the world open naturally as a consequence in the heart.

Just as Nāgārjuna [arguably the second most important figure in Buddhist philosophy] wrote: Without doubt, when practitioners have developed their understanding of emptiness, their minds will be devoted to the welfare of others.

Rob continues: We usually find too that our capacity and energy to actually serve also grow organically as our insight into emptiness matures.”

***

Meditation isn't a silver bullet

I imagine some of you might be thinking: "If meditation is so great, why don't more Buddhists and meditators seem to be tackling the world's most pressing problems?" I'm quite sympathetic to this criticism, and think the intention to be more (effectively) generous and ethical is crucial to combine with meditation.

Rob also echoes these concerns, in this talk where he discusses why Buddhists have been slow to act on climate change - the global problem he believed to be most pressing (it's a shame he hadn't encountered the EA community before passing away), and in this passage about the pitfalls of meditation from my favorite talk of his, The Power of the Generous Heart:

Insight meditation has strengths and pitfalls. Sometimes we come to this practice and we want emotional healing. A person wants a healing in their emotional life. And it’s a lovely thing to seek through practice. But I don’t know if a really deep emotional healing is actually possible without the heart opening in generosity. There was a study done for people suffering with depression. They found that one very significant quality that moved them out of the depression was actually helping other people – actually doing something in the world to help other people. And that opened something and lightened something.

So somehow, it’s very easy in this particular practice, insight meditation practice, to get into a belief, and again, it might not even be conscious, that a kind of self-preoccupation is going to bring healing. And it does to a certain degree. But I don’t know if there can be a really significant spiritual transformation without giving, without service, without this real cracking open of something in generosity. Now, this is not simple. This is not simple at all, because sometimes in our life we’re in a place where we need to do more inner work, we need to emphasize healing in an inner-looking kind of way. But there may be periods in life where that’s actually not the case, and the most healing thing is actually the opposite, coming out of the self.

So again, we assume very often – how easy it is to assume in these kind of practices (not just insight meditation; I mean lots of other related practices that even people in this room are doing), we assume that working on the self, on my relationship with experience and, especially difficult experience, my relationship with myself, assume that that’s the most important thing, assume that being with my unfolding experience, being with the unfolding of experience is the most important thing. But it can be – talk about strengths that can also be weaknesses – can be that I may be, in that, just perpetuating at a certain level, perpetuating a kind of self-centredness, and a kind of self-preoccupation, and the whole sense of self itself.

We begin to see, as we practise generosity deeply, the emptiness. It leads to wisdom and the seeing of emptiness – also the seeing of what leads to happiness and unhappiness. So wisdom brings generosity, wisdom leads to generosity, and generosity leads to wisdom. Sometimes I feel that the whole of the Dharma teachings are contained in generosity and the teachings on generosity. It’s all right there. It’s almost like we don’t need – if one practises deeply enough, don’t need anything else.

You know, I, certainly in others, and when I teach, I see that there is a connection. And I’m looking back on my practice, and I very much see a connection. And whatever openings, whatever humble openings there have been, or realizations, or depths or whatever, I really feel that generosity and the kind of willingness to stretch, has been … I see that in myself; it’s very much been a part of … almost like I can’t really, don’t trust that what has come would have come without the generosity. And I see it in others too. There’s this real correlation between opening, realization, and generosity. Huge part in it. Not to underestimate its power. Not to underestimate. To practise with it and see what opens. See what opens.

***

Though it has felt difficult at times, my life has so much more profound joy and contentment and meaning since deciding I wanted to become a bad-ass like the people in Strangers Drowning, and devote my life in service of making the future go as well as possible.

At times, it feels scary to let myself have such a lofty goal, and even scarier to admit it to others.

I am constantly messing up. I still waste much more time and succumb to far more selfish impulses than I aspire to. But in the same way I aspire to be kind and compassionate to others, I’m able to be light-hearted and gentle and patient with myself. I can forgive my numerous shortcomings, and savor everything that’s beautiful in trying really hard to be a good person. And I think, day by day, slowly, I am getting closer to becoming the person I aspire to be, motivating my altruism with compassion, courage, and optimism[1] instead of guilt, fear, and anxiety.

The future often seems bleak to me. From large scale AGI race dynamics and the trajectory of politics worldwide, to the basics of the food we eat and how we treat the people around us – it can often feel like society is permeated with apathy, and selfishness, and greed, and hatred, and a profound lack of concern for the wellbeing of others.

But I think we haven't tried hard enough to cultivate, to celebrate, to strengthen, to spread - in ourselves and in others - the positive qualities that can defeat them.

***

The timeless words of MLK

Two fitting quotes to end this talk from American civil rights champion Martin Luther King Jr:

He said the following in a speech, speaking about civil rights and the threat of nuclear catastrophe in the sixties. It applies just as strongly today, in light of how rapidly improving artificial intelligence and the rising threat of authoritarianism might transform society in the coming years:

This hour in history needs a dedicated circle of transformed nonconformists.... The saving of our world from pending doom will come, not through the complacent adjustment of the conforming majority, but through the creative maladjustment of a nonconforming minority... Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.

And closing with another banger of his:

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

The world is in desperate need of more scope-sensitive, impossible trade-off tackling, radically open–minded, love.

- ^

Optimism about what is possible, not (unwarranted) optimism about how things are now, or how they'll go by default.

Rohin Shah @ 2025-10-08T07:52 (+50)

I don’t know how much the FTX collapse is responsible for our current culture. They did cause unbelievable damage, acting extremely unethically and unilaterally and recklessly in destructive ways. But they did have this world-scale ambition, and urgency, and proclivity to actually make things happen in the world, that I think central EA orgs and the broader EA community sorely lack in light of the problems we’re hoping to solve.

But this is exactly why I don't want to encourage heroic responsibility (despite the fact that I often take on that mindset myself). Empirically, its track record seems quite bad, and I'd feel that way even if you ignore FTX.

Like, my sense is that something along the lines of heroic responsibility causes people to:

- Predictably bite off more than they can chew, and have massively reduced impact as a result

- If 100 people each solved 1% of a problem, you'd be in a good place. Instead, 100 EAs with heroic responsibility each try to solve 100% of the problem, and each solve 0.01% of it, and then you still have 99% left. (And in practice I expect many also move backwards.)

- Leave a genuinely impactful role because they can't see how it will solve everything (and then go on to something not as good)

- Cut corners due to increased urgency and responsibility, that leads to worse outcomes, because actually those corners were important

- Underestimate the value of conventional wisdom

- E.g. undervaluing the importance of management, ops, process, and maintenance, because it's hard to state a clear, legible theory of change for them that is as potentially-high-upside as something like research

- Trick themselves into thinking a bet is worth taking ("if this has even a 1% chance of working, it would be worth it" but actually the chance is more like 0.0001%)

To be clear in some sense these are all failures of epistemics, in that if you have sufficiently good epistemics then you wouldn't make any of these mistakes even if you were taking on heroic responsibility. But in practice humans are enough of an epistemic mess that I instead think that it's better to just not adopt heroic responsibility and instead err more in the direction of "the normal way to do things".

kuhanj @ 2025-10-08T08:56 (+17)

While I really like the HPMOR quote, I don't really resonate with heroic responsibility, and don't resonate with the "Everything is my fault" framing. Responsibility is a helpful social coordination tool, but it doesn't feel very "real" to me. I try to take the most helpful/impactful actions, even if they don't seem like "my responsibility" (while being cooperative and not unilateral and with reasonable constraints).

I'm sympathetic to taking on heroic responsibility causing harm in certain cases, but I don't see strong enough evidence that it causes more harm than good. The examples of moral courage from my talk all seem like examples of heroic responsibility with positive outcomes. The converse points to your bullets also generally seem more compelling to me:

1) It seems more likely to me that people taking too little responsibility for making the world better off has caused a lot more harm (like billionaires not doing more to reduce poverty, factory farming, climate change, AI risk, etc, or improve the media/disinformation landscape and political environment, etc). The harm is just much less visible since these are mostly failures of omission, not execution errors. It seems obvious to me the world could be much better off today, and the trajectory of the future could look much better than it does right now.

2) Not really the converse, but I don't know of anyone leaving an impactful role because they can't see how it will solve everything? I've never heard of anyone whose bar for taking on a job is "must be able to solve everything."

3) I see tons of apathy, greed, laziness, inefficiency, etc that lead to worse outcomes. The world is on fire in various ways, but the vast majority of people don't act like it.

4) Overvaluing conventional wisdom also causes tons of harm. How many well-resourced people never question general societal ethical norms (e.g. around the ethics of killing animals for food, or how much to donate, or how much social impact should be a priority in your career compared to salary, etc etc etc).

5) I'd argue EAs (and humans in general) are much more prone to prioritizing higher probability/certainty, lower-EV options over higher-EV, lower-probability options (Givewell donations over pro-global-health USG lobbying or political donations feels like a likely candidate). It's very emotionally difficult to do something that has a low chance of succeeding. AI safety does seem like a strong counterexample in the EA community, but I'd guess a lot of the community's members' prioritization of AI safety and specific work people do has more to do with intellectual interest and it being high-status in the community than rigorous impact-optimization.

Two cruxes for whether to err more in the direction of doing things the normal way: 1) How well you expect things to go by default. 2) How easy it is to do good vs. cause harm.

I don't feel great about 1), and honestly feel pretty good about 2), largely because I think that doing common-sense good things tends to actually be good, and doing good galaxy-brained ends-justify-the-means things that seem bad to normal people (like committing fraud or violence or whatever) are usually actually bad.

Rohin Shah @ 2025-10-08T19:02 (+11)

I'm totally on board with "if the broader world thought more like EAs that would be good", which seems like the thrust of your comment. My claim was limited to the directional advice I would give EAs.

kuhanj @ 2025-10-09T00:01 (+5)

Yea, fair point. Maybe this is just reference class tennis, but my impression is that a majority of people who consider themselves EAs aren't significantly prioritizing impact in their career and donation decisions, but I agree that for the subset of EAs who do, that "heroic responsibility"/going overboard can be fraught.

Some things that come to mind include how often EAs seem to work long hours/on weekends; how willing EAs are to do higher impact work when salaries are lower, when it's less intellectually stimulating, more stressful, etc; how many EAs are willing to donate a large portion of their income; how many EAs think about prioritization and population ethics very rigorously; etc. I'm very appreciative of how much more I see these in EA world than outside it, and I realize the above are unreasonable to expect from people.

Benevolent_Rain @ 2025-10-14T11:04 (+5)

Perhaps mentioned elsewhere here, but if we look for precedent for people doing an enormous amount of good (I can only think of Stanislav Petrov and people making big steps in curing disease), these actually did not act recklessly I think. It seems more like they persistently applied themselves to a problem, not super forcing an outcome and aligning a lot with others (like those eradicating smallpox). So if one wants a hero mindset, it might be good to emulate actual heroes we both think did a lot of good and that also reduced the risk of their actions.

ClaireZabel @ 2025-10-14T16:37 (+10)

I think there are examples supporting many different approaches and it depends immensely on what you're trying to do, the levers available to you and the surrounding context. E.g. in the more bold and audacious, less cooperative direction, Chiune Sugihara or Osckar Schindler come to mind. Petrov doesn't seem like a clear example in the "non-reckless" direction, and I'd put Arkhipov in a similar boat (they both acted rapidly under uncertainty in a way the people around them disagreed with, and took responsibility for a whole big situation when it probably would have been very easy to say to themselves that it wasn't their job to do things other than obey orders and go with the group).

Benevolent_Rain @ 2025-10-14T16:49 (+5)

I agree. Reading your comment made me think that it might be interesting — even if just as a small experiment — to map out which historical figures we feel struck the ~right balance between ambition and caution.

I don’t know if it would reveal much, but perhaps reading about a few such people could help me (and maybe others) better calibrate our own mix of drive and risk averseness. I find it easier to internalize these balances through real people and stories than through abstract arguments. And perhaps that kind of reflection could, in perhaps only a small way, help prevent future crises of judgment like FTX.

William_MacAskill @ 2025-10-06T10:20 (+30)

Thank you so much for writing this; I found a lot of it quite moving.

Since I read Strangers Drowning, this quote has really stuck in my mind:

"for do-gooders, it is always wartime"

And this from what you wrote resonates deeply, too:

"appreciate how wonderful it is to care about helping others."

"celebrate being part of a community that cares so much that we want to do so as effectively as we can."

Meditation and the cultivation of gratitude has been pretty transformative in my own life for my own wellbeing and ability to cope with living in a world in which it's always wartime. I'm so glad you've had the same experience.

kuhanj @ 2025-10-07T16:25 (+5)

Thanks Will! Our first chat back at Stanford in 2019 about how valuable EA community building and university group organizing are played an important role in me deciding to prioritize it over the following several years, and I'm very grateful I did! Thanks for the fantastic advice. :)

Mjreard @ 2025-10-06T16:37 (+24)

I keep coming back to Yeats on this topic:

"The best lack all conviction while the worst are filled with passionate intensity"

I think the exceptionally truth-seeking, analytical, and quantitative nature of EA is virtuous, but those virtues too easily translate into a culture of timidness if you don't consciously promote boldness.

Conceptually, Julia Galef talks about pairing social confidence with with epistemic humility in the Scout Mindset. It doesn't come naturally, but it is possible and valuable when done well.

Right now I think Nicholas Decker is a great embodiment of this ethos. He says what he thinks without fear or social hesitation. He's not always right and he flagrantly runs afoul of what's considered socially acceptable or what a PR consultant would tell him to do, but there's no mistaking his good-natured-ness and self-assurance that he's on the right side of history, because generally *he is.* He doesn't make the perfect the enemy of the good or excessively play it safe to avoid criticism.

A "bring on the haters" attitude is in fact more welcoming and trust-inducing than words carefully crafted to minimize criticism because it defeats the concern that you're hiding something. And come on friends, the stuff you're "hiding" in EA's case – veganism, shrimp, future generations, etc. – is nothing to be ashamed of. And when you soft roll it, you're endorsing the social sanction on these things as weird. Fuck that. Hit back. With grace. And pride. Fire the PR consultant in your head.

Toby_Ord @ 2025-10-15T10:26 (+12)

Thanks for this Kuhan — a great talk.

I'm intrigued about the idea of promoting a societal-level culture of substantially more altruism. It does feel like there is room for a substantial shift (from a very low base!) and it might be achievable.

SummaryBot @ 2025-10-06T16:25 (+5)

Executive summary: An exploratory, motivational talk argues that effective altruists should pair greater moral seriousness (heroic responsibility, ambition, and willingness to act at scale) with a more joyful, sustainable practice of ethics (cultivating generosity, compassion, and meditation-informed stability), contending that today’s negative trends (AI risk, animal suffering, misaligned incentives) won’t reverse without expanding our altruism—not just our effectiveness—while cautioning against guilt, extremism, and naïve EV-maximization.

Key points:

- Diagnosis of trajectory: Despite historic human progress, current trends—factory farming harms, slowdowns in poverty reduction, AI capabilities outpacing safety, and power concentration—suggest the default future may be bleak without deliberate moral renewal and cultural change.

- From effectiveness to altruism: EA over-optimizes how to help with fixed altruistic budgets; the author argues the bigger lever is increasing altruistic motivation and capacity (widening the moral circle, normalizing larger personal sacrifices), which then naturally drives interest in effectiveness.

- Heroic responsibility (with guardrails): The community should reclaim ambition, urgency, and ownership for outcomes (avoiding purely marginal thinking), while keeping non-violence, hard constraints, and lessons from FTX firmly in place to prevent reckless harm.

- Culture and incentives: Social incentives elevate power, wealth, and status over ethics; EA groups can counteract this by celebrating ethical commitment, defending EA’s core ideas publicly, and modeling courage that makes participation attractive rather than guilt-ridden.

- Enjoying the process: Drawing on Rob Burbea’s teachings, the post recommends cultivating generosity, compassion, and equanimity (e.g., via meditation) to ground sustained action; positive motivation is more durable and inspiring than guilt or fear.

- Practical implications for organizers: Foster communities that feel purposeful, kind, energetic, and fun; train minds toward desired virtues; highlight role models of moral courage (without endorsing harmful extremes); and keep sight of opportunity costs while remaining warm, forgiving, and optimistic about what’s achievable.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Tristan Katz @ 2025-10-15T21:05 (+1)

I enjoyed the original post, but found it somewhat hard to identify the key points and how they were connected. This summary makes that much clearer!

Jonas Hallgren 🔸 @ 2025-10-06T09:01 (+4)

Very very well put.

I became quite emotional when reading this because I resonated with it quite strongly. I've been in some longer retreats practicing the teachings in Seeing That Frees and I've noticed the connections between EA and Rob Burbea's way of seeing things but I haven't been able to express it well.

I think that there's a very beauitful deepening of a seeing of non-self when acting impartialy. One of the things that I really like about applying this to EA is that you often don't see the outcomes of your actions. This is often seen as a bad thing but from a vipassyana perspective this also somehow gets rid of the near enemy of loving kindness in purpose of getting something back. So it is almost like loving kindness based on EA principles is somehow less clinging than existing loving kindness practices?

I love the focus on the cultiavation of positive mental states as a foundation for doing effective work as well. Beautifully put, maybe one of my favourite forum posts of all time, thank you for writing this.

kuhanj @ 2025-10-08T08:14 (+3)

Thank you for the kind words Jonas!

Your comment reminded me of another passage from one of my favorite Rob talks, Selflessness and a Life of Love:

"Another thing about the abolitionist movement is that, if you look at the history of it, it actually took sixty or seventy or eighty years to actually make an effect. And some of the people who started it didn’t live to see the fruits of it. So there’s something about this giving myself to benefit others. I will never see them, I will never meet them, I will never get anything from them, whether that’s people or parts of the earth. And having this long view. And somehow it cannot be, in that case, about the limited self. It cannot be, because the limited self is not getting anything out of it. [...] But how might we have this sense of urgency without despair? Meeting the enormity of the suffering in the world with a sense of urgency in the heart, engagement in the heart, but without despair. How can we have, as human beings, a love that keeps going no matter what? And we call that ‘equanimity.’ It’s an aspect of equanimity, that it stays steady no matter what. The love, the compassion stays steady. [...] If we’re, in the practice, cultivating this sense of keeping the mind up and bright, and it’s still open, and it’s still sensitive, and the heart is open and receptive, but the consciousness is buoyant, that means it won’t sink when it meets the suffering in the world. The compassion will be buoyant."

idea21 @ 2025-10-05T16:44 (+3)

I rarely see the community discuss or emphasize how to increase our altruism, and our capacity for altruism, both on an individual and societal level

This observation is certainly welcome. Especially since I don't see how it can be utilitarian, from a cost-benefit perspective, to ignore the obvious urgency of having more altruistic people in order to have more altruistic works.

There are historical precedents of large social movements in which the altruistic motivation was considered a vital factor for community development. Unfortunately, this factor had to coexist with others that often distorted it. That is the point that needs to be improved. Evolution is copy plus modification.

Thanks, Kuhan.

Tristan Katz @ 2025-10-18T07:46 (+1)

I enjoyed this post a lot while reading it, but after reflecting (and discussing with my local group) I feel more unsure. Consider that can ask if we should encourage 'heroic responsibility' and try to foster this kind of radical, positive altruism at three different levels:

1. Personally, as an individual

2. Within EA

3. Within society as a whole.

The post seems to argue for all three. It talks specifically about the need for a cultural shift. I feel very convinced of (1) (I'd value this highly for myself), I'm less convinced of (2), and I feel quite unconvinced of (3).

Heroic responsibility & burnout

I think it's quite clear that it would be beneficial if this way of thinking became widespread in EA and society at large. But it's less clear if that's a realistic expectation. I actually see a lot of risks to encouraging heroic responsibility within EA; EA pivoted away from heroic responsibility toward more toned-down messaging about doing good quite intentionally. As kuhanj notes, without he positive, enjoying-the-process attitude that's argued for in part 2, there's the risk that heroic responsibility leads to burnout. And it seems to me that enjoying the process is actually not always that easy: meditation just isn't for everyone, I've meditated for a number of years and can't say it transformed me. I would be happy to see workshops on this at EA retreats, but it doesn't seem worth it to ask all EAs to spend large amounts of time on this when we're not sure if it'll work, and the current strategy of simply not asking people to take on all the world's problems also works ok. For people new to EA, the movement might also be very off-putting if it seemed to ask this much of you.

Is heroic responsibility learned or innate?

I also think that heroic responsibility might be determined more by genes or early childhood experiences than anything else. The examples of heroes don't seem to be of people who arrived there because of some deep insight - rather, these are people who were motivated by justice to begin with. I know for myself, I am more motivated in this way than my siblings now but I was also more motivated when I was 10 years old. Resources spent trying to transform people in this way might be wasted, and might be better spent by trying to encourage people who already have this disposition to join EA.