Reality has a surprising amount of detail

By Aaron Gertler 🔸 @ 2021-04-11T21:41 (+57)

This is a linkpost to http://johnsalvatier.org/blog/2017/reality-has-a-surprising-amount-of-detail

Note: I'm crossposting this because I often find myself referring to it in conversation. I often hear ideas or proposals that fail to account for the surprising amount of detail reality contains. Some of my own ideas and proposals fail for the same reason.

While the stereotype of people in EA as head-in-the-clouds philosophers doesn't fit most people I've met in the movement, we should still recognize those tendencies in ourselves when they arise, and remember how small details can multiply or reverse the impact we expect to have.

(Put another way, I think of this post as a clear introduction to crucial considerations.)

My favorite lines:

You might hope that these surprising details are irrelevant to your mission, but not so. Some of them will end up being key.

[...]

You might also hope that the important details will be obvious when you run into them, but not so. Such details aren’t automatically visible, even when you’re directly running up against them. Things can just seem messy and noisy instead.

[...]

Frames are made out of the details that seem important to you. The important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them. This all makes makes it difficult to imagine how you could be missing something important.

The post

I.

My dad emigrated from Colombia to North America when he was 18 looking looking for a better life. For my brother and I that meant a lot of standing outside in the cold. My dad’s preferred method of improving his lot was improving lots, and my brother and I were “voluntarily” recruited to help working on the buildings we owned.

That’s how I came to spend a substantial part of my teenage years replacing fences, digging trenches, and building flooring and sheds. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned from all this building, it’s that reality has a surprising amount of detail.

This turns out to explain why its so easy for people to end up intellectually stuck. Even when they’re literally the best in the world in their field.

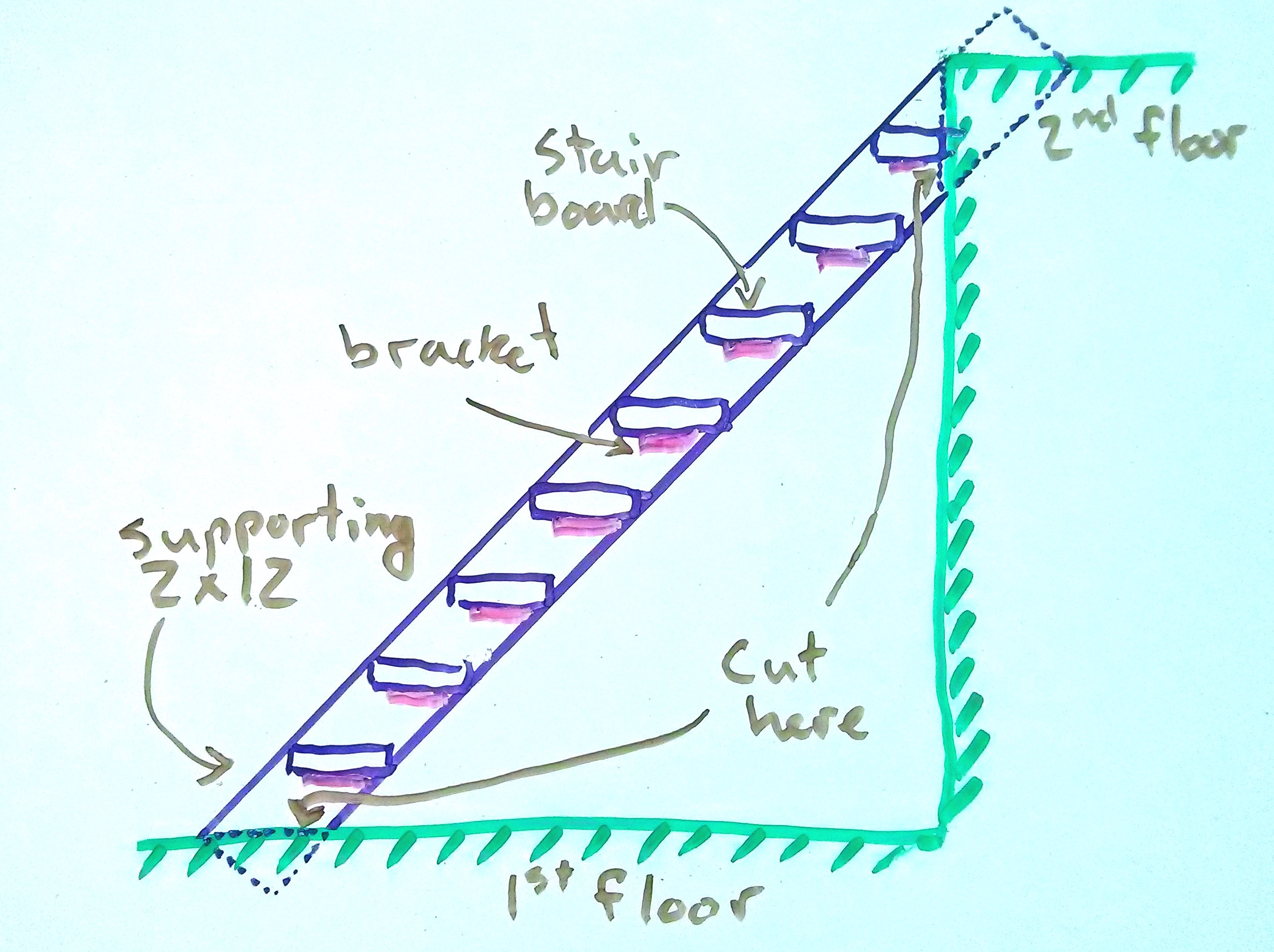

Consider building some basement stairs for a moment. Stairs seem pretty simple at first, and at a high level they are simple, just two long, wide parallel boards (2” x 12” x 16’), some boards for the stairs and an angle bracket on each side to hold up each stair. But as you actually start building you’ll find there’s a surprising amount of nuance.

The first thing you’ll notice is that there are actually quite a few subtasks. Even at a high level, you have to cut both ends of the 2x12s at the correct angles; then screw in some u-brackets to the main floor to hold the stairs in place; then screw in the 2x12s into the u-brackets; then attach the angle brackets for the stairs; then screw in the stairs.

Next you’ll notice that each of those steps above decomposes into several steps, some of which have some tricky details to them due to the properties of the materials and task and the limitations of yourself and your tools.

The first problem you’ll encounter is that cutting your 2x12s to the right angle is a bit complicated because there’s no obvious way to trace the correct angles. You can either get creative (there is a way to trace it), or you can bust out your trig book and figure out how to calculate the angle and position of the cuts.

You’ll probably also want to look up what are reasonable angles for stairs. What looks reasonable when you’re cutting and what feels safe can be different. Also, you’re probably going to want to attach a guide for your circular saw when cutting the angle on the 2x12s because the cut has to be pretty straight.

When you’re ready to you will quickly find that getting the stair boards at all the same angle is non-trivial. You’re going to need something that can give you an angle to the main board very consistently. Once you have that, and you’ve drawn your lines, you may be dismayed to discover that your straight looking board is not that straight. Lumber warps after it’s made because it was cut when it was new and wet and now it’s dryer, so no lumber is perfectly straight.

Once you’ve gone back to the lumber store and gotten some straighter 2x12s and redrawn your lines, you can start screwing in your brackets. Now you’ll learn that despite starting aligned with the lines you drew, after screwing them in, your angle brackets are no longer quite straight because the screws didn’t go in quite straight and now they tightly secure the bracket at the wrong angle. You can fix that by drilling guide holes first. Also you’ll have to move them an inch or so because it’s more or less impossible to get a screw to go in differently than it did the first time in the same hole.

Now you’re finally ready to screw in the stair boards. If your screws are longer than 2”, you’ll need different ones, otherwise they will poke out the top of the board and stab you in the foot.

At every step and every level there’s an abundance of detail with material consequences.

It’s tempting to think ‘So what?’ and dismiss these details as incidental or specific to stair carpentry. And they are specific to stair carpentry; that’s what makes them details. But the existence of a surprising number of meaningful details is not specific to stairs. Surprising detail is a near universal property of getting up close and personal with reality.

You can see this everywhere if you look. For example, you’ve probably had the experience of doing something for the first time, maybe growing vegetables or using a Haskell package for the first time, and being frustrated by how many annoying snags there were. Then you got more practice and then you told yourself ‘man, it was so simple all along, I don’t know why I had so much trouble’. We run into a fundamental property of the universe and mistake it for a personal failing.

If you’re a programmer, you might think that the fiddliness of programming is a special feature of programming, but really it’s that everything is fiddly, but you only notice the fiddliness when you’re new, and in programming you do new things more often.

You might think the fiddly detailiness of things is limited to human centric domains, and that physics itself is simple and elegant. That’s true in some sense – the physical laws themselves tend to be quite simple – but the manifestation of those laws is often complex and counterintuitive.

II. Boiling A Watched Pot

Consider the boiling of water. That’s straightforward, water boils at 100 °C, right?

Well the stairs seemed simple too, so let’s double check.

Put yourself in the shoes of someone at the start of the 1800’s, with only a crude, unmarked mercury thermometer, trying to figure the physics of temperature.

Go to your stove, put some water in a pot, start heating some water, and pay attention as it heats.

(I suggest actually doing this)

The first thing you’ll probably notice is a lot of small bubbles gathering on the surface of the pot. Is that boiling? The water’s not that hot yet; you can still even stick your finger in. Then the bubbles will appear faster and start rising, but they somehow seem ‘unboiling’. Then you’ll start to see little bubble storms in patches, and you start to hear a hissing noise. Is that Boiling? Sort of? It doesn’t really look like boiling. The bubble storms grow larger and start releasing bigger bubbles. Eventually the bubbles get big and the surface of the water grows turbulent as the bubbles begin to make it to the surface. Finally we seem to have reached real boiling. I guess this is the boiling point? That seems kind of weird, what were the things that happened earlier if not boiling.

To make matters worse, if you’d used a glass pot instead of a metal one, the water would boil at a higher temperature. If you cleaned the glass vessel with sulfuric acid, to remove any residue, you’d find that you can heat water substantially more before it boils and when it does boil it boils in little explosions of boiling and the temperature fluctuates unstably.

Worse still, if you trap a drop of water between two other liquids and heat it, you can raise the temperature to at least 300 °C with nothing happening. That kind of makes a mockery of the statement ‘water boils at 100 °C’.

It turns out that ‘boiling’ is a lot more complicated than you thought.

This surprising amount of detail is is not limited to “human” or “complicated” domains, it is a near universal property of everything from space travel to sewing, to your internal experience of your own mind.

III. Invisible vs. Transparent Detail And Getting Intellectually Stuck

Again, you might think ‘So what? I guess things are complicated but I can just notice the details as I run into them; no need to think specifically about this’. And if you are doing things that are relatively simple, things that humanity has been doing for a long time, this is often true. But if you’re trying to do difficult things, things which are not known to be possible, it is not true.

The more difficult your mission, the more details there will be that are critical to understand for success.

You might hope that these surprising details are irrelevant to your mission, but not so. Some of them will end up being key. Wood’s tendency to warp means it’s more accurate to trace a cut than to calculate its length and angle. The possibility of superheating liquids means it’s important to use a packed bed when boiling liquids in industrial processes lest your process be highly inefficient and unpredictable. The massive difference in weight between a rocket full of fuel and an empty one means that a reusable rocket can’t hover if it can’t throttle down to a very small fraction of its original thrust, which in turn means it must plan its trajectory very precisely to achieve 0 velocity at exactly the moment it reaches the ground.

You might also hope that the important details will be obvious when you run into them, but not so. Such details aren’t automatically visible, even when you’re directly running up against them. Things can just seem messy and noisy instead. ‘Spirit’ thermometers, made using brandy and other liquors, were in common use in the early days of thermometry. They were even considered as a potential standard fluid for thermometers. It wasn’t until the careful work of Swiss physicist Jean-André De Luc in the 18th century that physicists realized that alcohol thermometers are highly nonlinear and highly variable depending on concentration, which is in turn hard to measure.

You’ve probably also had experiences where you were trying to do something and growing increasingly frustrated because it wasn’t working, and then finally, after some time you realize that your solution method can’t possibly work.

Another way to see that noticing the right details is hard, is that different people end up noticing different details. My brother and I once built a set of stairs for the garage with my dad, and we ran into the problem of determining where to cut the long boards so they lie at the correct angle. After struggling with the problem for a while (and I do mean struggling, a 16’ long board is heavy), we got to arguing. I remembered from trig that we could figure out angle so I wanted to go dig up my textbook and think about it. My dad said, ‘no, no, no, let’s just trace it’, insisting that we could figure out how to do it.

I kept arguing because I thought I was right. I felt really annoyed with him and he was annoyed with me. In retrospect, I think I saw the fundamental difficulty in what we were doing and I don’t think he appreciated it (look at the stairs picture and see if you can figure it out), he just heard ‘let’s draw some diagrams and compute the angle’ and didn’t think that was the solution, and if he had appreciated the thing that I saw I think he would have been more open to drawing some diagrams. But at the same time, he also understood that diagrams and math don’t account for the shape of the wood, which I did not appreciate. If we had been able to get these points across, we could have come to consensus. Drawing a diagram was probably a good idea, but computing the angle was probably not. Instead we stayed annoyed at each other for the next 3 hours.

Before you’ve noticed important details they are, of course, basically invisible. It’s hard to put your attention on them because you don’t even know what you’re looking for. But after you see them they quickly become so integrated into your intuitive models of the world that they become essentially transparent. Do you remember the insights that were crucial in learning to ride a bike or drive? How about the details and insights you have that led you to be good at the things you’re good at?

This means it’s really easy to get stuck. Stuck in your current way of seeing and thinking about things. Frames are made out of the details that seem important to you. The important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them. This all makes makes it difficult to imagine how you could be missing something important.

That’s why if you ask an anti-climate change person (or a climate scientist) “what could convince you you were wrong?” you’ll likely get back an answer like “if it turned out all the data on my side was faked” or some other extremely strong requirement for evidence rather than “I would start doubting if I noticed numerous important mistakes in the details my side’s data and my colleagues didn’t want to talk about it”. The second case is much more likely than the first, but you’ll never see it if you’re not paying close attention.

If you’re trying to do impossible things, this effect should chill you to your bones. It means you could be intellectually stuck right at this very moment, with the evidence right in front of your face and you just can’t see it.

This problem is not easy to fix, but it’s not impossible either. I’ve mostly fixed it for myself. The direction for improvement is clear: seek detail you would not normally notice about the world. When you go for a walk, notice the unexpected detail in a flower or what the seams in the road imply about how the road was built. When you talk to someone who is smart but just seems so wrong, figure out what details seem important to them and why. In your work, notice how that meeting actually wouldn’t have accomplished much if Sarah hadn’t pointed out that one thing. As you learn, notice which details actually change how you think.

If you wish to not get stuck, seek to perceive what you have not yet perceived.