A History of Global Development

By DavidNash @ 2025-06-24T15:06 (+38)

Summary

I've recently completed a 7 week series on global development, I thought it would be useful to share each week on the forum as well in case people missed the announcement post.

The aim is to give people a more comprehensive overview of the global development landscape, either for those considering working/donating in this area, or if you are already in development but want to consider switching focus.

It seemed to me that resources in development & EA spaces were narrowly focused, with an emphasis on RCT backed healthcare interventions via non profits and I'm hoping to give people a broader understanding, so they can make more informed decisions on where to allocate their resources.

Here is a list of the different areas covered:

- A history of global development

- Evidence-based interventions, RCTs & Global Health

- Democracy, Institutions and Government

- Economic growth

- The Private Sector

- Innovation & Metascience

- AI and the Future of Development

I've added the first part below and will post the next few over the following days.

Also, I'm looking for critical feedback and suggestions of missing resources, etc. So far everyone has been quite positive and I'm hoping this forum will be able to point out mistakes and highlight the weaker parts.

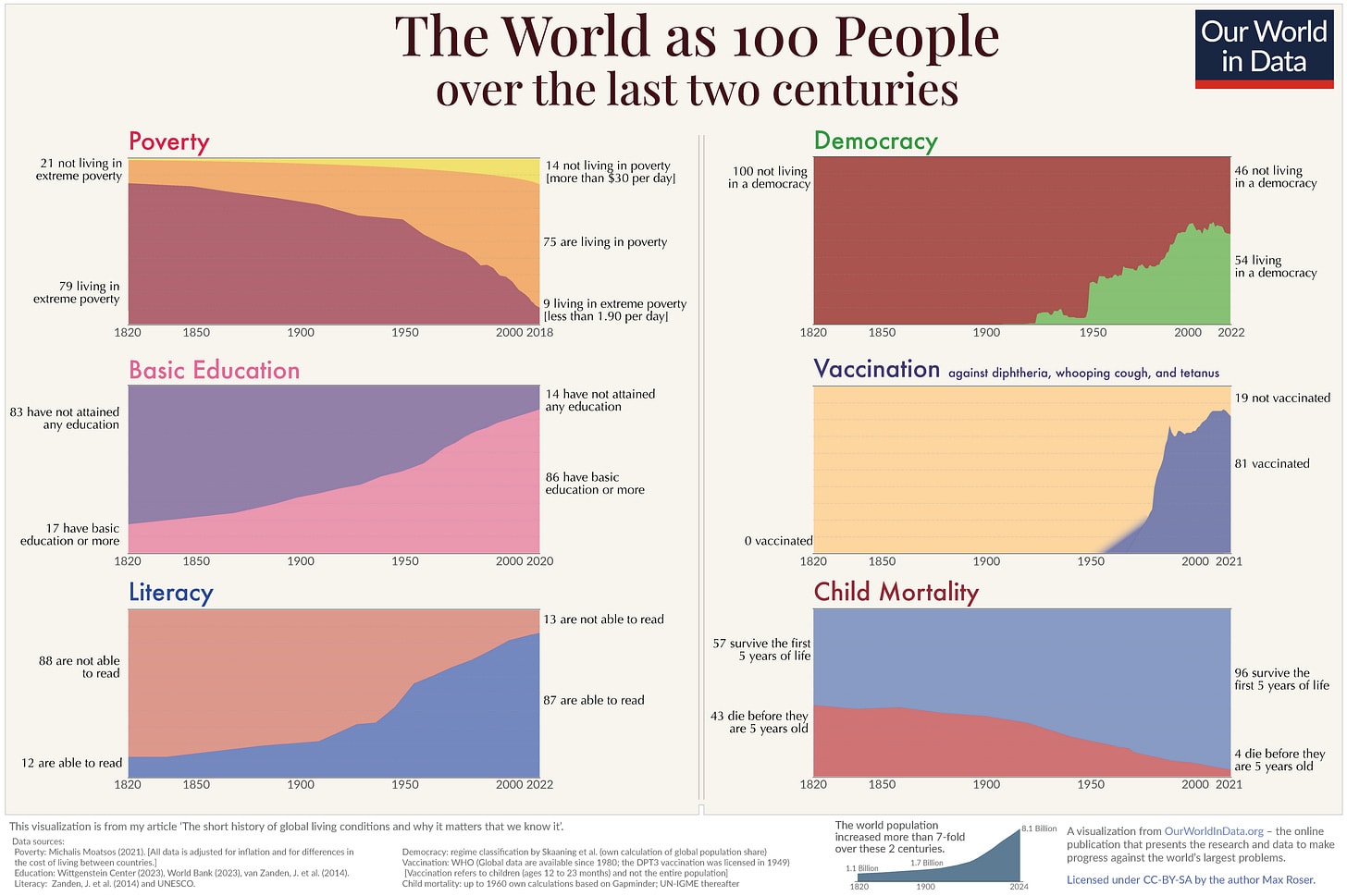

The Last 200 Years in Data

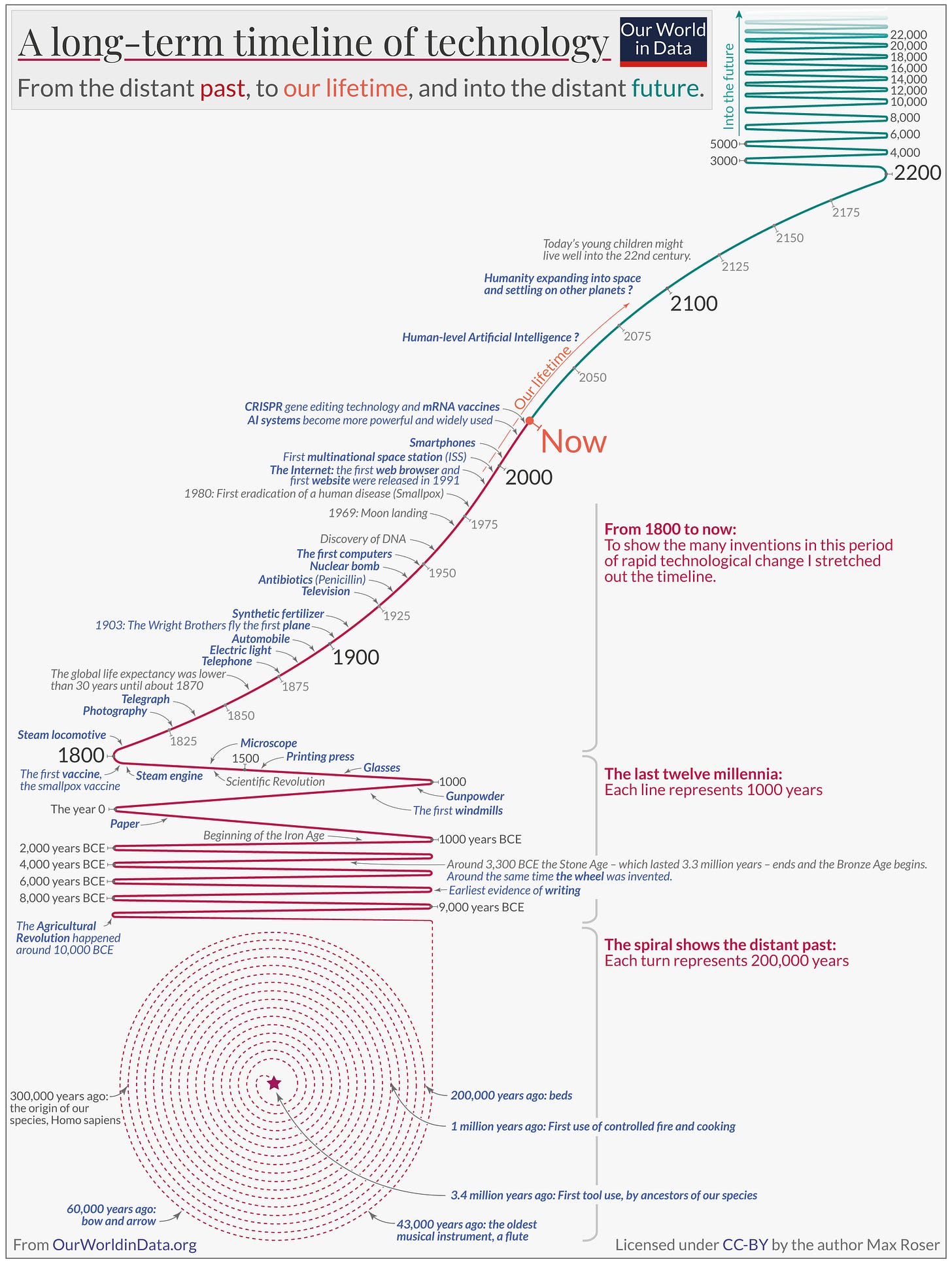

Before diving into specific areas, it's useful to understand the scope of change over the past two centuries. This section is focused on the data on how life has changed since 1820, with particular attention to improvements in health, wealth and general wellbeing.

- Hans Rosling - New Insights on Poverty (video - 18 minutes)

Hans Rosling's talk covers these changes in an easy to follow way and was pivotal in sparking my own interest in global development nearly 20 years ago. Our World in Data has been another invaluable resource I've followed for years, helping to make sense of complex, often counter-intuitive trends that affect billions of people worldwide. These resources both offer compelling visualisations and context that often challenge misconceptions about global progress.

- Max Roser - The short history of global living conditions (10 min)

Transformative Areas for Welfare

The improvements in welfare over the last two centuries didn't happen by chance. They resulted from innovations, movements and institutional changes that transformed how societies function. This section highlights some key areas that drove improvements. Understanding these developments helps explain why progress occurred where and when it did, and could provide insights into how further advances might be achieved.

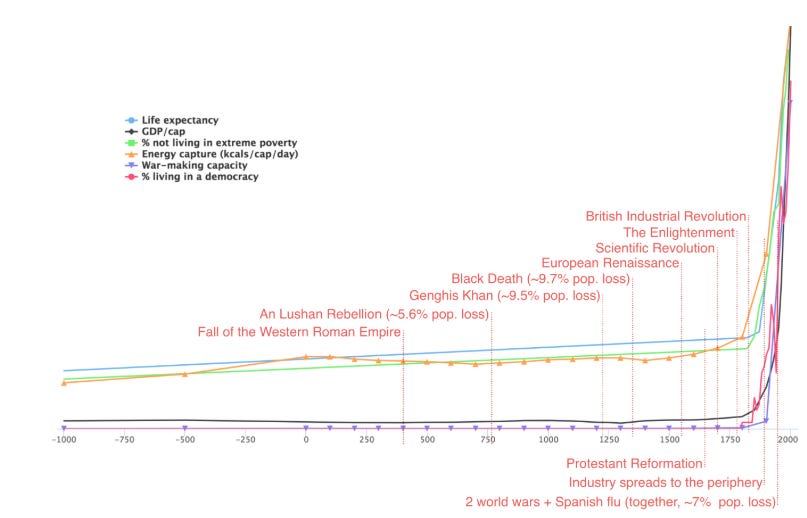

Industrial Revolution

The transition from agrarian economies to industrial ones began in the late 18th century and introduced mechanisation, factory systems and mass production techniques. While initially concentrated in Great Britain and Europe, these changes gradually spread globally, creating new patterns of economic development and international trade. The increased productive capacity eventually enabled rising living standards across many societies, though often with significant social disruption.

Luke Muehlhauser - How big a deal was the Industrial Revolution? (axes removed for space reasons)

Vaccines & Public Health

Vaccines have significantly reduced mortality from infectious diseases since their development in the 19th century. Prior to modern public health measures, approximately half of all children died before adulthood, with infectious diseases being a primary cause. The discovery of germ theory enabled the creation of vaccines that train the immune system to recognise specific pathogens. This led to the eradication of smallpox, a 99% reduction in polio cases globally and a decrease in measles deaths from 2.6 million annually to 83,000.

- Max Roser - Our history is a battle against the microbes: we lost terribly before science, public health and vaccines allowed us to protect ourselves (5 min)

Public health innovations:

- Sanitary Reform Movement

- The 1840s saw the first systematic attempts at sanitary reform. Britain's Public Health Act of 1848, established a centralised health authority to address urban water, sewerage and sanitation

- Disease Tracking Methods

- John Snow mapped cholera cases in London in 1854, identifying a contaminated water pump as the source. This applied geographical and statistical methods to disease tracking, establishing epidemiology as a field focused on disease sources rather than ‘bad air’ theories

- Germ Theory Applications

- 19th century work by Pasteur and Koch established that specific microorganisms cause specific diseases. Researchers identified disease vectors enabling targeted prevention

- Infrastructure Development

- Cities implemented sewers, clean water supplies, garbage collection and disease notification requirements. The Vaccination Act of 1853 introduced compulsory smallpox vaccination in England and Wales

Agricultural Transformation

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Green Revolution dramatically increased agricultural production around the world. At a time of rapid population growth, this boost in production reduced hunger, helped to avert famine and stimulated economies. It brought about the large-scale use of technology, including high-yielding crop varieties, improved irrigation systems and increased synthetic fertiliser use.

- Hannah Ritchie - Yields vs. land use: how the Green Revolution enabled us to feed a growing population

Energy

Before the Industrial Revolution, people relied on limited energy forms: wind, water, muscle power and burning fuels with few means to transform, store or transmit the fuels. The steam engine marked the first energy revolution by converting heat into mechanical power, followed by oil and gas which provided fuels that were easier to transport. The discovery of electricity then allowed energy to be converted into other forms, transmitted over long distances and applied cleanly in many different ways.

These transformations in energy systems have dramatically increased productivity and quality of life through electrification, mechanisation, transportation, etc. Energy access has extended productive hours beyond daylight, enabled refrigeration and modern healthcare and facilitated global communication networks.

- Jason Crawford - The Significance of Electricity (5 min)

Approximately 3 billion people still lack access to clean cooking fuels and rely on wood and charcoal, with an estimated 3.8 million annual deaths from resulting diseases.

- Max Roser - Energy poverty and indoor air pollution (6 min)

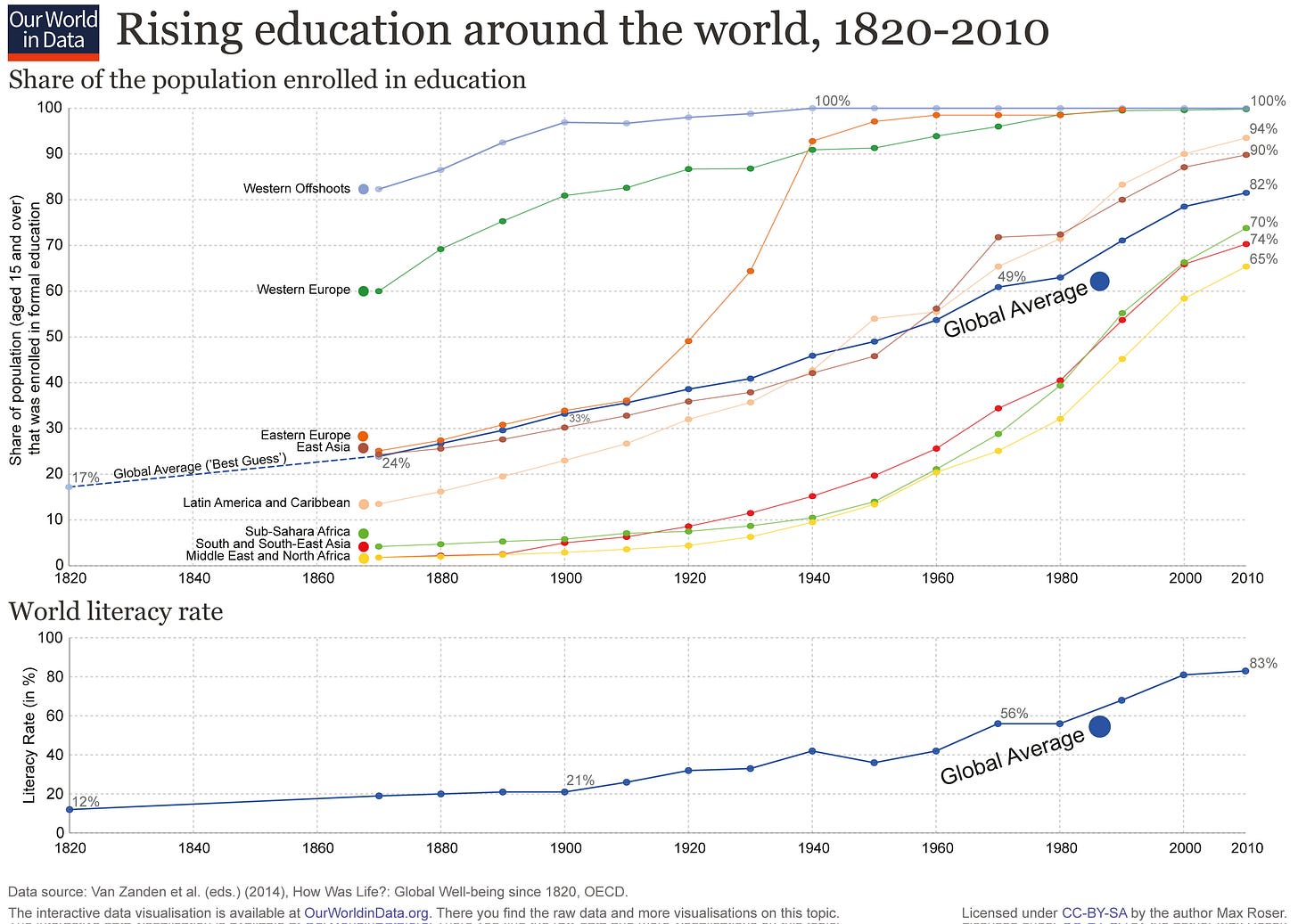

Education

Education can transform individual lives and equip societies to address pressing challenges. Over the last 200 years, humanity has undergone a transformation in educational access and outcomes.

- Literacy rates have risen from just 12% globally in 1820 to over 80% today

- The spread of education preceded and enabled industrial development, with literate populations driving innovation and economic growth

- Recent years have seen accelerated progress, with countries in Latin America, Northern Africa and the Middle East achieving in generations what took centuries in early-industrialised nations

- Our World in Data - When and why did more people become literate? How can progress continue? (5 min)

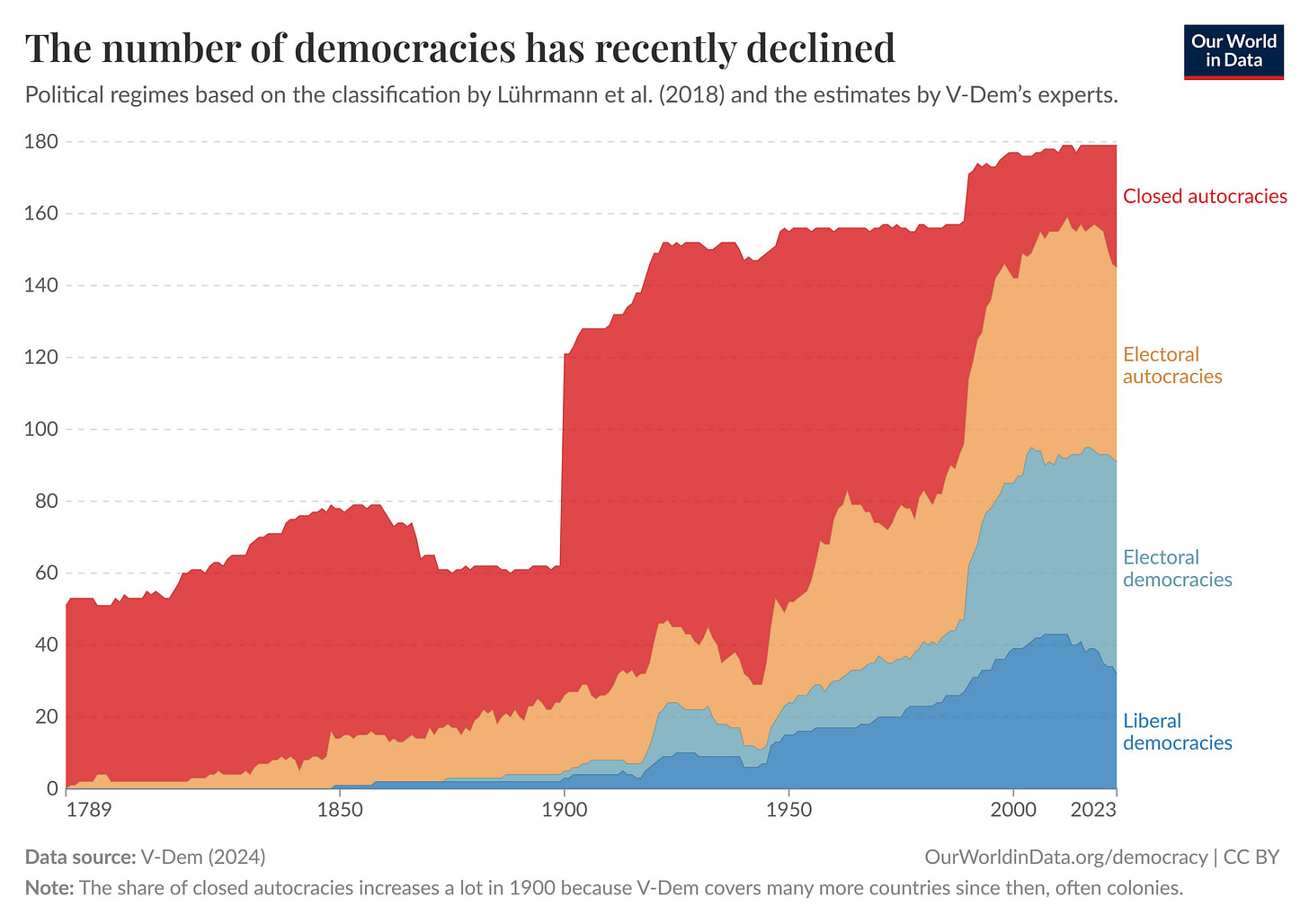

Democracy and Rights

Democracy has spread from a handful of countries to become the predominant form of government worldwide. Increasing democracy typically supports development through stronger property rights, reduced corruption and greater investment in public goods. Countries with democratic institutions generally experience more sustainable long-term growth, though this is context-dependent.

- Bastian Herre - 200 years ago, everyone lacked democratic rights. Now, billions of people have them - Although it’s not a linear path, there are lots of forward and backward steps

- While some countries have developed successfully under democracy, others, like South Korea and Taiwan, achieved rapid economic growth under authoritarian systems before democratising

- Democratic systems create accountability mechanisms that typically direct resources toward broader development priorities like education and healthcare

- Although issues like regulatory capture or elite influence can persist despite democratic institutions

- The expansion of rights and freedoms represents both a means to development and an end in itself, reflecting progress beyond economic metrics to include dignity and agency

Scientific Advancement

The Scientific Revolution (1500s) preceded and enabled the industrial revolution by creating both specific technical knowledge (understanding of vacuums and atmospheric pressure crucial for steam engines) and establishing methodological frameworks.

The institutional infrastructure of science (journals, societies and universities) created more paths for knowledge preservation, verification and transmission that prevented the loss of innovations and enabled cumulative technological progress in ways not possible in pre-scientific societies.

- Telecommunications infrastructure, evolving from telegraph to fiber optics to smart phones through institutional R&D, with massively decreased information transfer costs, enabling economic integration that reduced global poverty

- Genetic engineering advancements created both medical breakthroughs (insulin production, gene therapies) and agricultural improvements that addressed nutritional deficiencies affecting billions worldwide

- Integrated circuit development at research institutions like Bell Labs enabled the computing revolution, with processing power increasing 10-million-fold, leading to personal computers, the internet, AI and robotics that advanced virtually every industry

Critiques of modern day science include reproducibility, publication bias, limited cross-disciplinary insights, short-term grant cycles favoring incremental, low-risk research, paywalls, citation obsession and commercialisation pressures.

Global Governance

Institutions

There are different types of institutions that impact global development. Governmental and private sector ones are covered in other sections but here the focus is on large non (national) governmental organisations. This could include foundations (Gates, Wellcome), regional unions (African Union, EU, NATO) and universities.

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organisation established after World War II, focused on preventing future conflicts and protecting human rights & international law.

The broader UN System has multiple specialised agencies including:

- World Health Organization

- Directs international health work through setting standards, monitoring health trends and coordinating responses to health emergencies

- United Nations Development Programme

- Focuses on development, democratic governance and crisis recovery

- World Food Programme

- Delivers food assistance in emergencies and works to improve nutrition

- UNICEF

- Promotes children's rights and well-being

- World Bank Group

- Provides loans and grants to countries for capital projects with the aim of reducing poverty

- Originally a separate organisation, and still has a different governing structure

UN agencies have led vaccination campaigns that eradicated smallpox (and nearly eradicated polio) and established development goals as coordination frameworks. There are critiques about the amount of bureaucracy, response times and political deadlocks when representing many countries.

Bretton Woods Institutions

The Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 had delegates from allied nations shape the post-World War II global financial framework. This led to the creation of:

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) - Serves as a lender of last resort for governments

- The World Bank - Made up of two institutions that provide loans and grants to low and middle-income countries:

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development - Offers loans to middle-income countries

- International Development Association - Offers concessional loans and grants to the poorest countries

Following the reconstruction of Europe, the Bank's mandate expanded to advancing worldwide economic development and eradicating poverty. They have been criticised for their structural adjustment programs in the 80’s & 90’s, governance structures dominated by richer countries, and for prioritising economic metrics over social welfare outcomes. There have also been critiques more recently about the World Bank focusing on social outcomes rather than growing economies (especially when relating to concerns more common in high income countries).

Ha-Joon Chang - Understanding the Relationship between Institutions and Economic Development - A critique of the World Bank and IMF

Evidence & Resources in Development

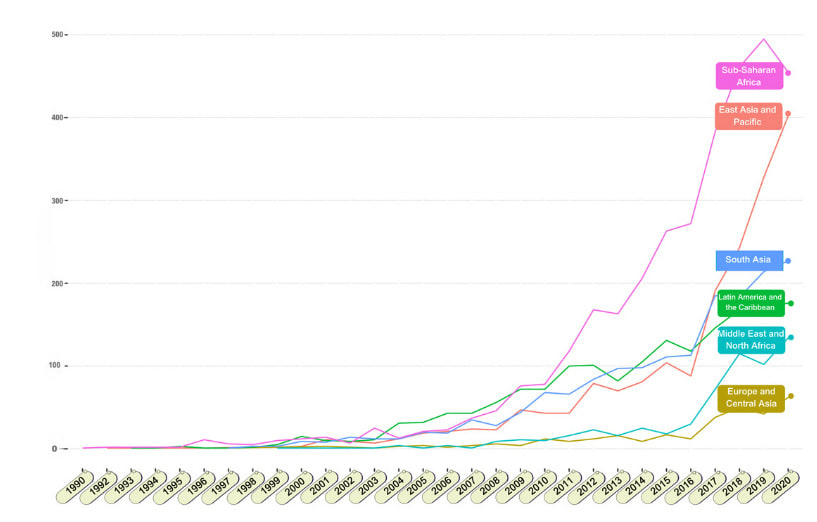

Randomised Controlled Trials & Impact Evaluation

From the early 2000s, development economics saw the rise of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quantitative impact evaluations. This approach marked a shift from theoretical models toward evidence-based policymaking. Multiple institutions emerged to promote these ideas, including the Poverty Action Lab (later J-PAL), Innovations for Poverty Action and the Development Impact Evaluation unit at the World Bank. The approach gained prominence by providing evidence on which interventions improved outcomes in areas like education, health, and poverty reduction.

Chart showing the number of impact evaluations on 3ie’s Development Evidence Portal over time

While RCTs have changed the development landscape, they've also faced criticism regarding reliability, costs and limited generalisability. Major donors including aid agencies and philanthropic foundations have increasingly prioritised evidence-based approaches in their funding decisions.

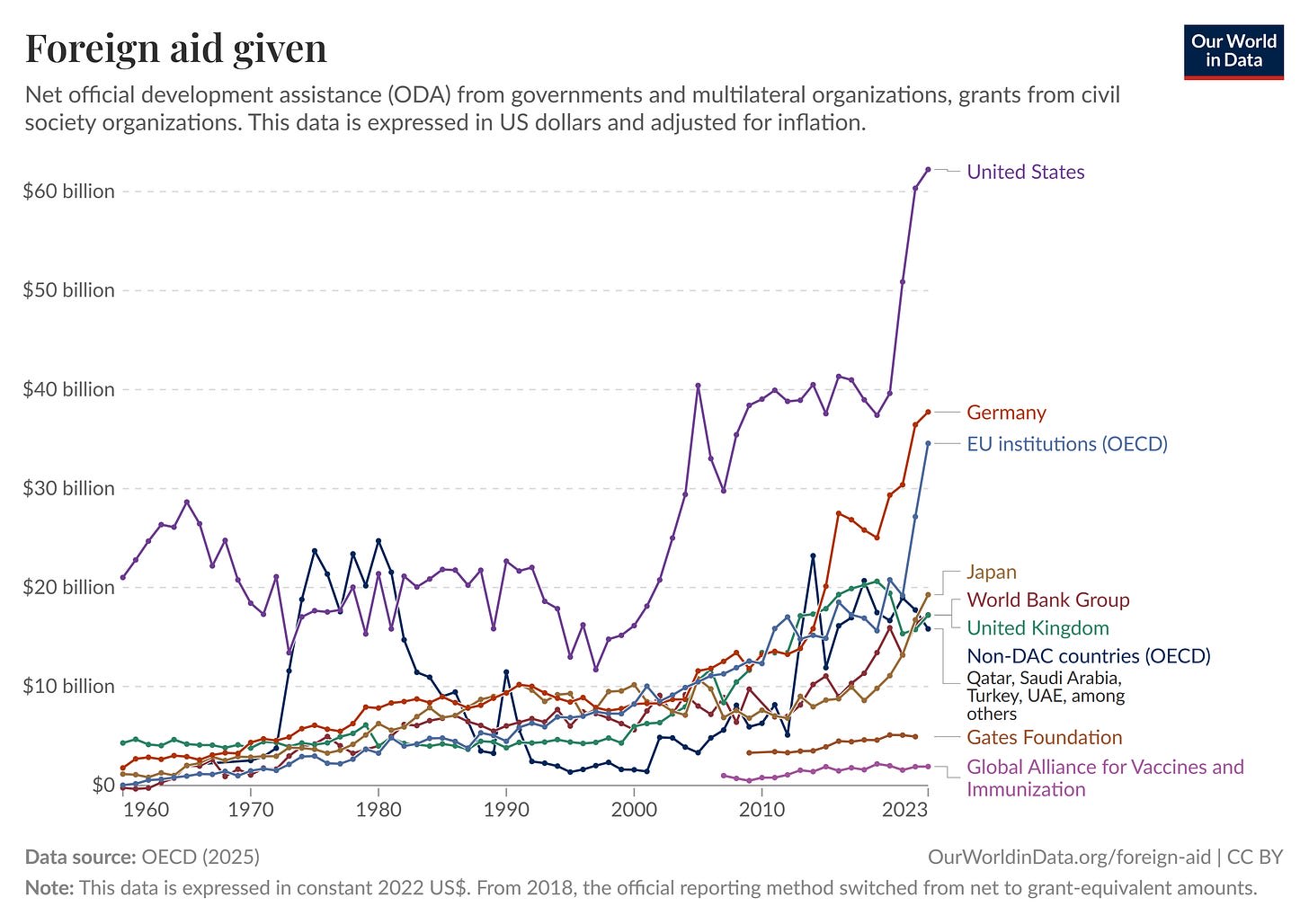

Foreign Aid

Foreign aid has undergone multiple transformations since the 1960s, evolving from a Cold War strategic tool to an ecosystem addressing global development challenges.

By 2023, official development assistance reached over $200 billion globally, reflecting increased commitments and an expanding scope. This figure encompasses both traditional development programming but also substantial flows to conflict-affected and fragile states. While military aid is excluded from ODA calculations, humanitarian and reconstruction support for conflict zones represent a significant portion of contemporary aid flows.

The record of foreign aid is varied across sectors and regions. Programs like PEPFAR, GAVI's vaccination campaigns, and the near-eradication of guinea worm disease demonstrate aid's potential to save millions of lives, while failures like the WHO's abandoned malaria eradication efforts of the 1950s and India's coercive sterilisation programs reveal its capacity to waste resources or cause harm.

Critics highlight how aid can distort accountability away from citizens toward donors, undermine local economic development, create dependency, or be captured by elites.

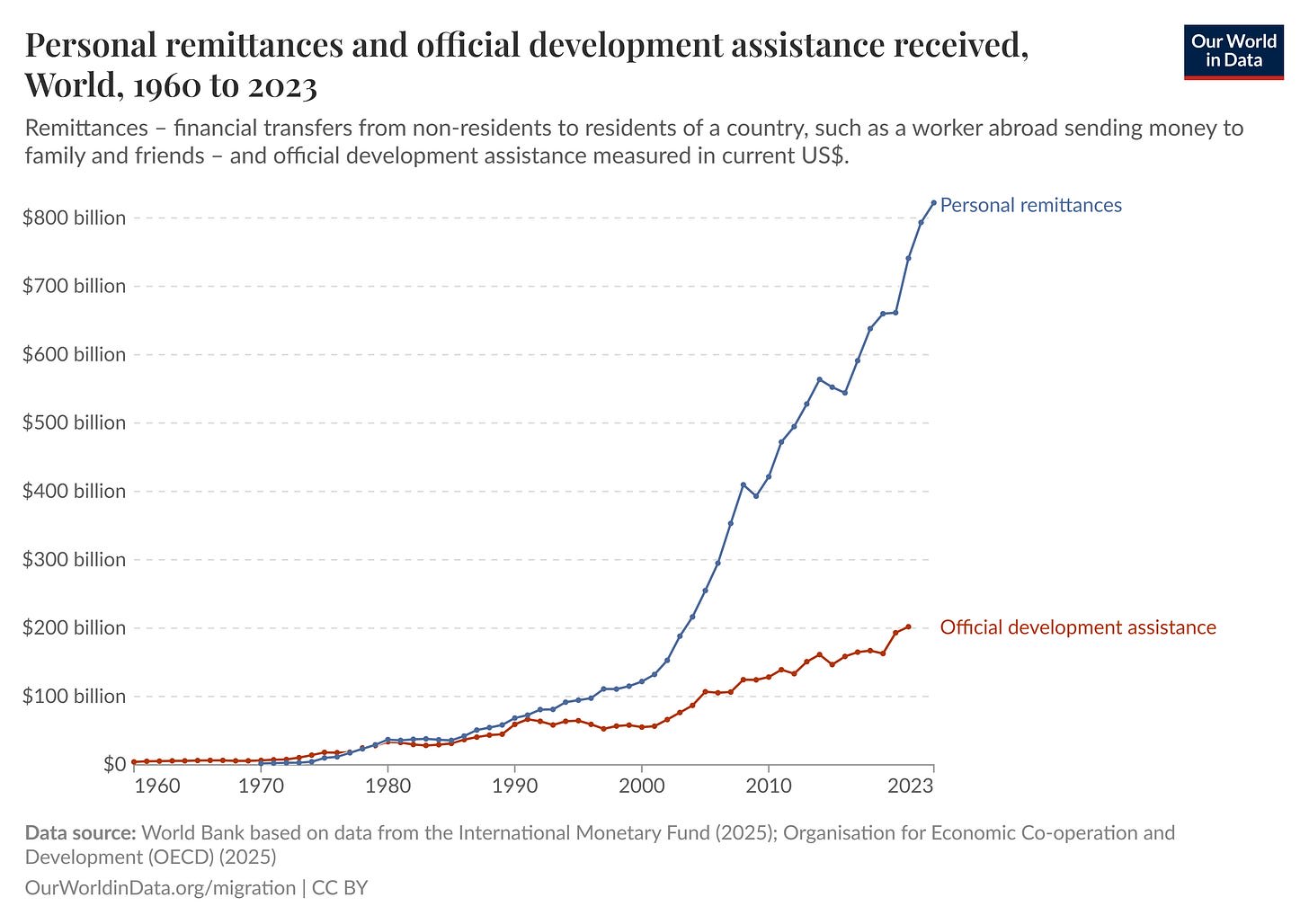

Remittances

Remittances have emerged as one of the more significant forces in poverty reduction. While their informal practice dates back centuries, remittances gained prominence during the late 20th century as global migration increased. By 2024, these financial flows have reached over $800 billion annually, three times larger than official development assistance.

The significance of remittances lies in their directness and scale. Unlike other forms of development assistance, these funds flow directly to families, bypassing institutional intermediaries and governmental bureaucracies. They predominantly move from high-income countries to middle-income countries, helping pay for things like education, healthcare and food. Remittances still have challenges including high transaction fees, currently averaging 6% globally and they also don’t tend to go towards the poorest countries and so although it is much larger than ODA it may have a smaller impact overall, and seems less likely to enable more systemic change.

Our World in Data - The great global redistributor we never hear about: money sent or brought back by migrants (5 min)

Economic Engines of Development

Government Revenue & Spending

Government spending is essential for public services and infrastructure. Since the 1990s, domestic resource mobilisation is the fastest-growing source of development financing, far outpacing external assistance.

- Domestic revenues dominate development financing, with LMIC countries (excluding China and India) getting around $2.3 trillion through government revenues in 2011 - approximately 80% of total development financing

- Grieve Chelwa - African governments should, and can, collect more in taxes

- Increasing the tax-to-GDP ratio in Africa from its current rate of 16% to the Asia-Pacific average of 19% or the LAC average of 22% would…yield average additional tax revenues of between $80 - 160 billion. Higher than the total ODA for Africa in 2022

- Yaw - Book Review #3: Where Credit is Due - (7 min)

- A good overview of why countries borrow and how they raise money

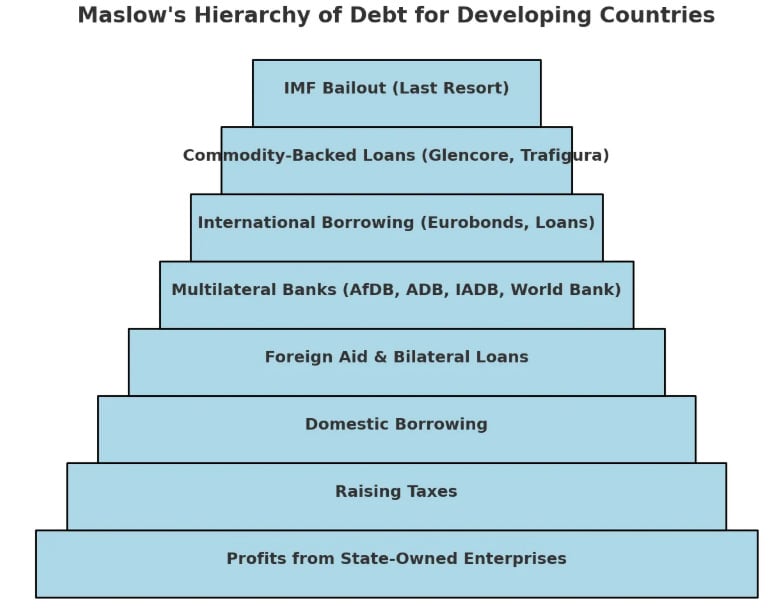

- Countries follow a ‘hierarchy of debt’ when funding government activities, starting with profits from state-owned enterprises and taxation, then progressing to domestic borrowing, foreign aid, multilateral loans and IMF bailouts as a last resort

- Many poorer countries rely on revenue from state-owned oil, mining and strategic assets rather than taxes. Resource-dependent economies face extreme budget volatility as their revenues fluctuate with commodity prices, illustrated by oil revenue comprising over 50% of government budgets in countries like Libya (97%), Equatorial Guinea (80%) and Nigeria (65%)

- Taxation remains challenging in many African nations due to poverty, corporate tax avoidance and reliance on consumption taxes like VAT, resulting in low tax-to-GDP ratios. There is also an issue of increasing spending on debt repayments

Yaw’s self made visualisation

The Private Sector

Periods of higher private investment are historically associated with more rapid reductions in extreme poverty. The countries that had the greatest success in reducing poverty often saw private investment that generated growth in urban areas, and used that growth to pay for public investment programmes (roads, electrification, irrigation) and social spending (health, education, social protection).

By current estimates, the private sector accounts for approximately 60% of GDP and 90% of jobs in developing economies. The private sector drives development through multiple channels: creating productive employment, generating tax revenue, building and operating infrastructure, delivering goods and services, spurring innovation, and developing human capital through workforce training.

Growth fails to reduce poverty when the economic linkages to people are weak, and governments fail to use the proceeds either to encourage the spread of economic activity or for anti-poverty programmes. Some of the most egregious examples are in countries where growth was concentrated in resource extraction, such as Angola and Equatorial Guinea, while other countries such as Botswana and Indonesia have been more likely to make investments aimed at reducing poverty.

Critics highlight how market failures, rent-seeking behavior and regulatory capture can undermine the private sector's development contribution. Monopolistic practices, environmental externalities, labor exploitation and tax avoidance represent significant challenges. In countries with weak institutions, private enterprise can reinforce rather than reduce poverty, particularly when economic opportunities cluster around political connections rather than competitive merit.

The most successful development models have featured strategic complementarity between markets and state, where governments created enabling conditions for private sector growth while addressing coordination failures and externalities. This suggests neither unfettered markets nor heavy state control alone optimises development outcomes.

- Karthik Tadepalli - The central question of development economics is simple: how can poor countries become rich? The answer is neither small-scale, targeted interventions nor broad generalisations about growth. Instead, we should focus on firms (7 min)

If you're interested, you can find part 2 here - Evidence-based interventions, RCTs & Global Health.