Reducing suffering given long-term cluelessness

By Magnus Vinding @ 2025-06-26T17:53 (+36)

This is a linkpost to https://magnusvinding.com/2025/06/25/reducing-suffering-given-long-term-cluelessness/

An objection against trying to reduce suffering is that we cannot predict whether our actions will reduce or increase suffering in the long term. Relatedly, some have argued that we are clueless about the effects that any realistic action would have on total welfare, and this cluelessness, it has been claimed, undermines our reason to help others in effective ways. For example, DiGiovanni (2025) writes: “if my arguments [about cluelessness] hold up, our reason to work on EA causes is undermined.”

There is a grain of truth in these claims: we face enormous uncertainty when trying to reduce suffering on a large scale. Of course, whether we are bound to be completely clueless about the net effects of any action is a much stronger and more controversial claim (and one that I am not convinced of). Yet my goal here is not to discuss the plausibility of this claim. Rather, my goal is to explore the implications if we assume that we are bound to be clueless about whether any given action overall reduces or increases suffering.

In other words, without taking a position on the conditional premise, what would be the practical implications if such cluelessness were unavoidable? Specifically, would this undermine the project of reducing suffering in effective ways? I will argue not. Even if we grant complete cluelessness and thus grant that certain moral views provide no practical recommendations, we can still reasonably give non-zero weight to other moral views that do provide practical recommendations. Indeed, we can find meaningful practical recommendations even if we hold a purely consequentialist view that is exclusively concerned with reducing suffering.

A potential approach: Giving weight to scope-adjusted views

There might be many ways to ground a reasonable focus on effective suffering reduction even if we assume complete cluelessness about long-term consequences. Here, I will merely outline one candidate option, or class of options, that strikes me as fairly reasonable.

As a way to introduce this approach, say that we fully accept consequentialism in some form (notwithstanding various arguments against being a pure consequentialist, e.g. Knutsson, 2023; Vinding, 2023). Yet despite being fully convinced of consequentialism, we are uncertain or divided about which version of consequentialism is most plausible.

In particular, while we give most weight to forms of consequentialism that entail no restrictions or discounts in its scope, we also give some weight to views that entail a more focused scope. (Note that this kind of approach need not be framed in terms of moral uncertainty, which is just one possible way to frame it. An alternative is to think in terms of degrees of acceptance or levels of agreement with these respective views, cf. Knutsson, 2023, sec. 6.6.)

To illustrate with some specific numbers, say that we give 95 percent credence to consequentialism without scope limitations or adjustments of any kind, and 5 percent credence to some form of scope-adjusted consequentialism. The latter view may be construed such that its scope roughly includes those consequences we can realistically estimate and influence without being clueless. This view is similar to what has been called “reasonable consequentialism”, the view that “an action is morally right if and only if it has the best reasonably expected consequences.” It is also similar to versions of consequentialism that are framed in terms of foreseeable or reasonably foreseeable consequences (Sinnott-Armstrong, 2003, sec. 4).

To be clear, the approach I am exploring here is not committed to any particular scope-adjusted view. The deeper point is simply that we can give non-zero weight to one or more scope-adjusted versions of consequentialism, or to scope-adjusted consequentialist components of a broader moral view. Exploring which scope-adjusted view or views might be most plausible is beyond the aims of this essay, and that question arguably warrants deeper exploration.

That being said, I will mostly focus on views centered on (something like) consequences we can realistically assess and be guided by, since something in this ballpark seems like a relatively plausible candidate for scope-adjustment. I acknowledge that there are significant challenges in clarifying the exact nature of this scope, which is likely to remain an open problem subject to continual refinement. After all, the scope of assessable consequences may grow as our knowledge and predictive power grow.

Asymmetry in practical recommendations

The relevance of the approach outlined above becomes apparent when we evaluate the practical recommendations of the clueless versus non-clueless views incorporated in this approach. A completely clueless consequentialist view would give us no recommendations about how to act, whereas a non-clueless scope-adjusted view would give us practical recommendations. (It would do so by construction if its scope includes those consequences we can realistically estimate and influence without being clueless.)

In other words, the resulting matrix of recommendations from those respective views is that the non-clueless view gives us substantive guidance, while the clueless view suggests no alternative and hence has nothing to add to those recommendations. Thus, if we hold something like the 95/5 combined consequentialist view described above — or indeed any non-zero split between these component views — it seems that we have reason to follow the non-clueless view, all things considered.

Toy models

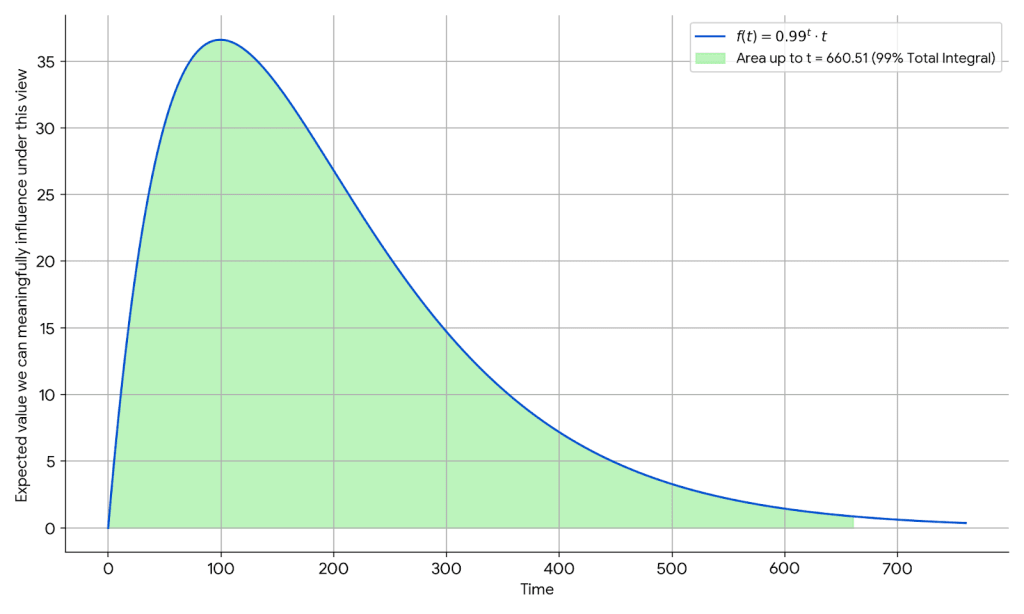

To give a sense of what a scope-adjusted view might look like, we can consider a toy model with an exponential discount factor and an (otherwise) expected linear increase in population size:

The green area represents 99 percent of the total expected value we can influence under this view, implying that almost all the value we can meaningfully influence is found within the next 700 years.

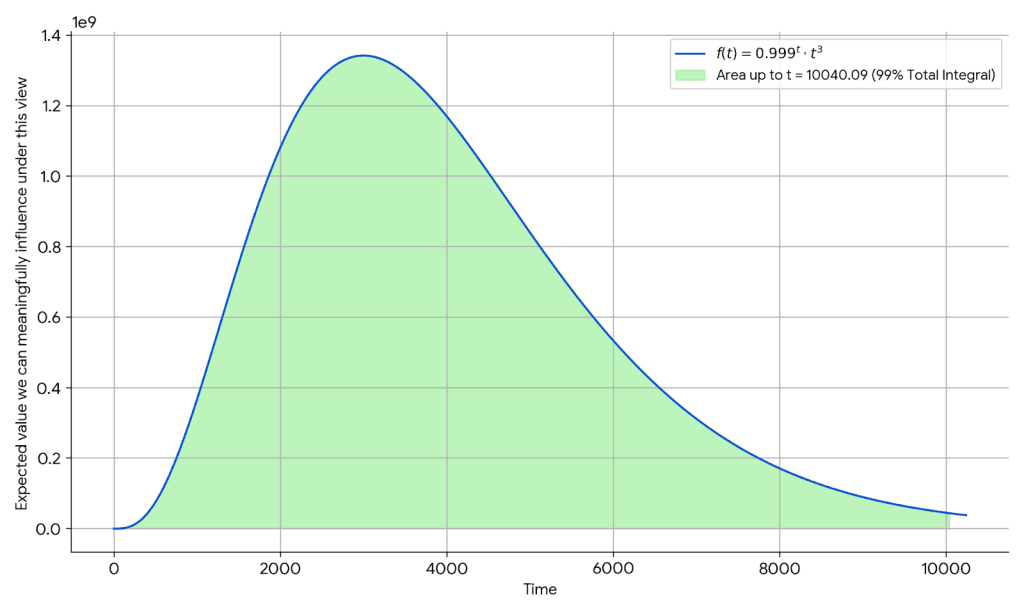

We can also consider a model with a different discount factor and with cubic growth, reflecting the possibility of space expansion radiating from Earth:

On this model, virtually all the expected value we can meaningfully influence is found within the next 10,000 years. In both of the models above, we end up with a sort of de facto “medium-termism”.

Of course, one can vary the parameters in numerous ways and combine multiple models in ways that reflect more sophisticated views of, for example, expected future populations and discount factors. Views that involve temporal discounting allow for much greater variation than what is captured by the toy models above, including views that focus on much shorter or much longer timescales. Moreover, views that involve discounting need not be limited to temporal discounting in particular, or even be phrased in terms of temporal discounting at all. It is one way to incorporate discounting or scope-adjustments, but by no means the only one.

Furthermore, if we give some plausibility to views that involve discounting of some kind, we need not be committed to a single view for every single domain. We may hold that the best view, or the view we give the greatest weight, will vary depending on the issue at hand (cf. Dancy, 2001; Knutsson, 2023, sec. 3). A reason for such variability may be that the scope of outcomes we can meaningfully predict often differs significantly across domains. For example, there is a stark difference in the predictability of weather systems versus planetary orbits, and similar differences in predictability might be found across various practical and policy-relevant domains.

Note also that a non-clueless scope-adjusted view need not be rigorously formalized; it could, for example, be phrased in terms of our all things considered assessments, which might be informed by myriad formal models, intuitions, considerations, and so on.

Justifications and motivations

What might justify or motivate the basic approach outlined above? This question can be broken into two sub-questions. First, why give weight to more than just a single moral view? Second, provided we give some weight to more than a single view, why give any weight to a scope-adjusted view concerned with consequences?

Why give weight to multiple views?

Reasons for giving weight to more than a single moral view or theory have been explored elsewhere (see e.g. Dancy, 2001; MacAskill et al., 2020, ch. 1; Knutsson, 2023; Vinding, 2023).

One of the reasons that have been given is that no single moral theory seems able to give satisfying answers to all moral questions (Dancy, 2001; Knutsson, 2023). And even if our preferred moral theory appears to be a plausible candidate for answering all moral questions, it is arguably still appropriate to have less than perfect confidence or acceptance in that theory (MacAskill et al., 2020, ch. 1; Vinding, 2023). Such moderation might be grounded in epistemic modesty and humility, a general skepticism toward fanaticism, and the prudence of diversifying one’s bets. It might also be grounded partly in the observation that other thoughtful people hold different moral views and that there is something to be said in favor of those views.

Likewise, giving exclusive weight to a single moral view might make us practically indifferent or paralyzed, whether it be due to cluelessness or due to underspecification as to what our preferred moral theory implies in some real-world situation. Critically, such practical indifference and paralysis may arise even in the face of the most extreme atrocities. If we find this to be an unreasonable practical implication, we arguably have reason not to give exclusive weight to a moral view that potentially implies such paralysis.

Finally, from a perspective that involves degrees of acceptance or agreement with moral views, a reason for giving weight to multiple views might simply be that those moral views each seem intuitively plausible or that we intuitively agree with them to some extent (cf. Knutsson, 2023, sec. 6.6).

Why give weight to a scope-adjusted view?

What reasons could be given for assigning weight to a scope-adjusted view in particular? One reason may be that it seems reasonable to be concerned with consequences to the extent that we can realistically estimate and be guided by them. That is arguably a sensible and intuitive scope for concern about consequences — or at least it appears sensible to some non-zero degree. If we hold this intuition, even if just to a small degree, it seems reasonable to have a final view in which we give some weight to a view focused on realistically assessable consequences (whatever the scope of those consequences ultimately turns out to be).

Some support may also be found in our moral assessments and stances toward local cases of suffering. For example, if we were confronted with an emergency situation in which some individuals were experiencing intense suffering in our immediate vicinity, and if we were readily able to alleviate this suffering, it would seem morally right to help these beings even if we cannot foresee the long-run consequences. (All theoretical and abstract talk aside, I suspect the vast majority of consequentialists would agree with that position in practice.)

Presumably, at least part of what would make such an intervention morally right is the badness of the suffering that we prevent by intervening. And if we hold that it is morally appropriate to intervene to reduce suffering in cases where we can immediately predict the consequences of doing so — namely that we alleviate the suffering right in front of us — it seems plausible to hold that this stance also generalizes to consequences that are less immediate. In other words, if this stance is sound in cases of immediate suffering prevention — or even if it just has some degree of soundness in such cases — it plausibly also has some degree of soundness when it comes to suffering prevention within a broader range of consequences that we can meaningfully estimate and influence.

This is also in line with the view that we have (at least somewhat) greater moral responsibility toward that which occurs within our local sphere of assessable influence. This view is related to, and may be justified in terms of, the “ought implies can” principle. After all, if we are bound to be clueless and unable to deliberately influence very long-run consequences, then, if we accept some version of the “ought implies can” principle, it seems that we cannot have any moral responsibility or moral duties to deliberately shape those long-run consequences — or at least such moral responsibility is plausibly diminished. In contrast, the “ought implies can” principle is perfectly consistent with moral responsibility within the scope of consequences that we realistically can estimate and deliberately influence in a meaningful way.

Thus, if we give some weight to an “ought implies can” conception of moral responsibility, this would seem to support the idea that we have (at least somewhat) greater moral responsibility toward that which occurs within our sphere of assessable influence. An alternative way to phrase it might be to say that our sphere of assessable influence is a special part of the universe for us, in that we are uniquely positioned to predict and steer events in that part compared to elsewhere, and this arguably gives us a (somewhat) special moral responsibility toward that part of the universe.

Another potential reason to give some weight to views centered on realistically assessable consequences, or more generally to views that entail discounting in some form, is that other sensible people endorse such views based on reasons that seem defensible to some degree. For example, it is common for economists to endorse models that involve temporal discounting, not just in descriptive models but also in prescriptive or normative models (see e.g. Arrow et al., 1996). The justifications for such discounting might be that our level of moral concern should be adjusted for uncertainty about whether there will be any future, uncertainty about our ability to deliberately influence the future, and the possibility that the future will be better able to take care of itself and its problems (relative to earlier problems that we could prioritize instead).

One might object that such reasons for discounting should be incorporated at a purely empirical level, without any discounting at the moral level, and I would largely agree with that sentiment. (Note that when applied at a strictly empirical or practical level, those reasons and adjustments are contenders as to how one might avoid paralysis without any discounting at the moral level.)

Yet even if we think such considerations should mostly or almost exclusively be applied at the empirical level, it might still be defensible to also invoke them to justify some measure of discounting directly at the level of one’s moral view and moral concerns, or at least as a tiny sub-component within one’s broader moral view. In other words, it might be defensible to allow empirical considerations of the kind listed above to inform and influence our fundamental moral values, at least to a small degree.

To be clear, it is not just some selection of economists who endorse normative discounting or scope-adjustment in some form. As noted above, it is also found among those who endorse “reasonable consequentialism” and consequentialism framed in terms of foreseeable consequences. And similar views can be found among people who seek to reduce suffering.

For example, Brian Tomasik has long endorsed a kind of split between reducing suffering effectively in the near term versus reducing suffering effectively across all time. In particular, regarding altruistic efforts and donations, he writes that “splitting is rational if you have more than one utility function”, and he devotes at least 40 percent of his resources toward short-term efforts to reduce suffering (Tomasik, 2015). Jesse Clifton seems to partially endorse a similar approach focused on reasons that we can realistically weigh up — an approach that in his view “probably implies restricting attention to near-term consequences” (see also Clifton, 2025). The views endorsed by Tomasik and Clifton explicitly give some degree of special weight to near-term or realistically assessable consequences, and these views and the judgments underlying them seem fairly defensible.

Lastly, it is worth emphasizing just how weak of a claim we are considering here. In particular, in the framework outlined above, all that is required for the simple practical asymmetry argument to go through is that we give any non-zero weight to a non-clueless view focused on realistically assessable consequences, or some other non-clueless view centered on consequences.

That is, we are not talking about accepting this as the most plausible view, or even as a moderately plausible view. Its role in the practical framework above is more that of a humble tiebreaker — a view that we can consult as an nth-best option if other views fail to give us guidance and if we give this kind of view just the slightest weight. And the totality of reasons listed here arguably justify that we grant it at least a tiny degree of plausibility or acceptance.

Arguments I have not made

One could argue that something akin to the approach outlined here would also be optimal for reducing suffering in expectation across all space and time. In particular, one could argue that such an unrestricted moral aim would in practice imply a focus on realistically assessable consequences. I am open to that argument — after all, it is difficult to see what else the recommended focus could be, to the extent there is one.

For similar reasons, one could argue that a practical focus on realistically assessable consequences represents a uniquely safe and reasonable bet from a consequentialist perspective: it is arguably the most plausible candidate for what a consequentialist view would recommend as a practical focus in any case, whether scope-adjusted or not. Thus, from our position of deep uncertainty — including uncertainty about whether we are bound to be clueless — it arguably makes convergent sense to try to estimate the furthest depths of assessable consequences and to seek to act on those estimates, at least to the extent that we are concerned with consequences.

Yet it is worth being clear that the argument I have made here does not rely on any of these claims or arguments. Indeed, it does not rely on any claims about what is optimal for reducing suffering across all space and time.

As suggested above, the conditional claim I have argued for here is ultimately a very weak one about giving minimal weight to what seems like a fairly moderate and in some ways commonsensical moral view or idea (e.g. it seems fairly commonsensical to be concerned with consequences to the extent that we can realistically estimate and be guided by them). The core argument presented in this essay does not require us to accept any controversial empirical positions.

Conclusion

For some of our problems, perhaps the best we can do is to find “second best solutions” — that is, solutions that do not satisfy all our preferred criteria, yet which are nevertheless better than any other realistic solution. This may also be true when it comes to reducing suffering in a potentially infinite universe. We might be in an unpredictable sea of infinite consequences that ripple outward forever (Schwitzgebel, 2024). But even if we are, this need not prevent us from trying to reduce suffering in effective and sensible ways within a realistic scope. After all, compared to simply giving up on trying to reduce suffering, it seems less arbitrary and more plausible to at least try to reduce suffering within the domain of consequences we can realistically assess and be guided by.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tobias Baumann, Jesse Clifton, and Simon Knutsson for helpful comments.

Writing this essay was a brief interim project between other projects, so I don't plan to engage with comments in the near future.

Anthony DiGiovanni @ 2025-06-27T13:27 (+5)

Thanks for this post, Magnus! While I’m still uncompelled by your arguments in “Why give weight to a scope-adjusted view” for the reasons discussed here and here, I’ll set that aside and respond to the “Asymmetry in practical recommendations”.

Suppose that (i) the normative perspective from which we’re clueless (e.g., impartial consequentialism plus my framework here) says both A and B are permissible, and (ii) all other normative perspectives we give weight to say only A is permissible. In that case, I’d agree we should do A, no matter how minuscule the weight we give to the perspectives in (ii).

But realistically, our situation doesn’t seem that clean. Take {A = “donate to the Humane Slaughter Association”, B = “spend that money on yourself”}. It seems that different scope-adjusted views might give the opposite verdict here. Let T be the time horizon beyond which the HSA donation might lead to, say, increased wild animal suffering via increasing the price of meat for larger farmed animals.

- If we discount fast enough, the effects before T (preventing painful slaughter) dominate ⇒ A is better than B.

- If we discount more slowly (but not so slowly that we’re clueless!), the backfire effect on wild animals after T might dominate ⇒ B is better than A.

(In practice things might be much more complicated than this model lets on. It’s just an illustration.)

We might try to put meta-normative weights on these different discount rates. But I expect the relative weights to be arbitrary, which would make us clueless all over again from a consequentialist perspective. (I’m not saying our normative views need to be precisely specified — they can and will be vague — but we need some perhaps-vague overall reason to think the A-favoring perspectives outweigh the B-favoring perspectives. And I’m still keen for people to think about what that kind of reason might be!)

SummaryBot @ 2025-06-27T19:34 (+1)

Executive summary: This exploratory essay argues that even if we are completely clueless about the long-term effects of our actions on suffering, we can still justifiably focus on reducing suffering within the scope of consequences we can realistically assess, by giving non-zero weight to "scope-adjusted" consequentialist views that offer practical guidance when others do not.

Key points:

- Cluelessness doesn't necessarily paralyze action: Even if we assume total long-term cluelessness about the net effects of our actions, we can still reasonably act on views that guide us within a scope of reasonably foreseeable consequences.

- Scope-adjusted consequentialism provides practical guidance: By assigning some weight to versions of consequentialism that prioritize assessable consequences (e.g. “reasonable consequentialism”), we retain action-guiding moral recommendations.

- Asymmetry justifies action: If one view gives no recommendations (due to cluelessness) and another gives actionable guidance (due to limited scope), it is rational to follow the latter even with minimal credence in it.

- Toy models illustrate “medium-termism”: Simple models suggest that most of the value we can influence lies within the next several centuries or millennia, offering a plausible time horizon for focused efforts.

- Giving weight to multiple views is epistemically and morally defensible: Moral uncertainty, practical paralysis, and modesty all support assigning partial weight to multiple plausible theories, including scope-adjusted ones.

- Moral responsibility may track assessability: The idea that “ought implies can” supports the notion that we have stronger duties within the domains we can realistically influence, making scope-adjusted views both intuitive and justified.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.