A framework for thinking about AI power-seeking

By Joe_Carlsmith @ 2024-07-24T22:41 (+48)

This post lays out a framework I’m currently using for thinking about when AI systems will seek power in problematic ways. I think this framework adds useful structure to the too-often-left-amorphous “instrumental convergence thesis,” and that it helps us recast the classic argument for existential risk from misaligned AI in a revealing way. In particular, I suggest, this recasting highlights how much classic analyses of AI risk load on the assumption that the AIs in question are powerful enough to take over the world very easily, via a wide variety of paths. If we relax this assumption, I suggest, the strategic trade-offs that an AI faces, in choosing whether or not to engage in some form of problematic power-seeking, become substantially more complex.

Prerequisites for rational takeover-seeking

For simplicity, I’ll focus here on the most extreme type of problematic AI power-seeking – namely, an AI or set of AIs actively trying to take over the world (“takeover-seeking”). But the framework I outline will generally apply to other, more moderate forms of problematic power-seeking as well – e.g., interfering with shut-down, interfering with goal-modification, seeking to self-exfiltrate, seeking to self-improve, more moderate forms of resource/control-seeking, deceiving/manipulating humans, acting to support some other AI’s problematic power-seeking, etc.[1] Just substitute in one of those forms of power-seeking for “takeover” in what follows.

I’m going to assume that in order to count as “trying to take over the world,” or to participate in a takeover, an AI system needs to be actively choosing a plan partly in virtue of predicting that this plan will conduce towards takeover.[2] And I’m also going to assume that this is a rational choice from the AI’s perspective.[3] This means that the AI’s attempt at takeover-seeking needs to have, from the AI’s perspective, at least some realistic chance of success – and I’ll assume, as well, that this perspective is at least decently well-calibrated. We can relax these assumptions if we’d like – but I think that the paradigmatic concern about AI power-seeking should be happy to grant them.

What’s required for this kind of rational takeover-seeking? I think about the prerequisites in three categories:

- Agential prerequisites – that is, necessary structural features of an AI’s capacity for planning in pursuit of goals.

- Goal-content prerequisites – that is, necessary structural features of an AI’s motivational system.

- Takeover-favoring incentives – that is, the AI’s overall incentives and constraints combining to make takeover-seeking rational.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Agential prerequisites

In order to be the type of system that might engage in successful forms of takeover-seeking, an AI needs to have the following properties:

- Agentic planning capability: the AI needs to be capable of searching over plans for achieving outcomes, choosing between them on the basis of criteria, and executing them.

- Planning-driven behavior: the AI’s behavior, in this specific case, needs to be driven by a process of agentic planning.

- Note that this isn’t guaranteed by agentic planning capability.

- For example, an LLM might be capable of generating effective plans, in the sense that that capability exists somewhere in the model, but it could nevertheless be the case that its output isn’t driven by a planning process in a given case – i.e., it’s not choosing its text output via a process of predicting the consequences of that text output, thinking about how much it prefers those consequences to other consequences, etc.

- And note that human behavior isn’t always driven by a process of agentic planning, either, despite our planning ability.

- Note that this isn’t guaranteed by agentic planning capability.

- Adequate execution coherence: that is, the AI’s future behavior needs to be sufficiently coherent that the plan it chooses now actually gets executed.

- Thus, for example, it can’t be the case that if the AI chooses some plan now, it will later begin pursuing some other, contradictory priority in a manner that makes the plan fail.

Note that human agency, too, often fails on this condition. E.g., a human resolves to go to the gym every day, but then fails to execute on this plan.[4]

- Takeover-inclusive search: that is, the AI’s process of searching over plans needs to include consideration of a plan that involves taking over (a “takeover plan”).

This is a key place that epistemic prerequisites like “strategic awareness”[5] and “situational awareness” enter in. That is, the AI needs to know enough about the world to recognize the paths to takeover, and the potential benefits of pursuing those paths.

- Even granted this basic awareness, though, the model’s search over plans can still fail to include takeover plans. We can distinguish between at least two versions of this.

- On the first, the plans in question are sufficiently bad, by the AI’s lights, that they would’ve been rejected had the AI considered them.

- Thus, for example, suppose someone asks you to get them some coffee. Probably, you don’t even consider the plan “take over the world in order to really make sure that you can get this coffee.” But if you did consider this plan, you would reject it immediately.

- This sort of case can be understood as parasitic on the “takeover-favoring incentives” condition below. That is, had it been considered, the plan in question would’ve been eliminated on the grounds that the incentives didn’t favor it. And its badness on those grounds may be an important part of the explanation for why it didn’t even end up getting considered – e.g., it wasn’t worth the cognitive resources to even think about.

- On the second version of “takeover conducive search” failing, the takeover plan in question would’ve actually been chosen by the AI system, had it considered the plan, but it still failed to do so.

- In this case, we can think of the relevant AI as making a mistake by its own lights, in failing to consider a plan. Here, an analogy might be a guilt-less sociopath who fails to consider the possibility of robbing their elderly neighbor’s apartment, even though it would actually be a very profitable plan by their own lights.

- On the first, the plans in question are sufficiently bad, by the AI’s lights, that they would’ve been rejected had the AI considered them.

- Note that if we reach the point where we’re able to edit or filter what sorts of plans an AI even considers, we might be able to eliminate consideration of takeover plans at this stage.

Goal-content prerequisites

Beyond these agential prerequisites, an AI’s motivational system – i.e., the criteria it uses in evaluating plans – also needs to have certain structural features in order for paradigmatic types of rational takeover-seeking to occur. In particular, it needs:

Consequentialism: that is, some component of the AI’s motivational system needs to be focused on causing certain kinds of outcomes in the world.[6]

This condition is important for the paradigm story about “instrumental convergence” to go through. That is, the typical story predicts AI power-seeking on the grounds that power of the relevant kind will be instrumentally useful for causing a certain kind of outcome in the world.

There are stories about problematic AI power-seeking that relax this condition (for example, by predicting that an AI will terminally value a given type of power), but these, to my mind, are much less central.

Note, though, that it’s not strictly necessary for the AI in question, here, to terminally value causing the outcomes in question. What matters is that there is some outcome that the AI cares about enough (whether terminally or instrumentally) for power to become helpful for promoting that outcome.

Thus, for example, it could be the case that the AI wants to act in a manner that would be approved of by a hypothetical platonic reward process, where this hypothetical approval is not itself a real-world outcome. However, if the hypothetical approval process would, in this case, direct the AI to cause some outcome in the world, then instrumental convergence concerns can still get going.

Adequate temporal horizon: that is, the AI’s concern about the consequences of its actions needs to have an adequately long temporal horizon that there is time both for a takeover plan to succeed, and for the resulting power to be directed towards promoting the consequences in question.[7]

Thus, for example, if you’re supposed to get the coffee within the next five minutes, and you can’t take over the world within the next five minutes, then taking over the world isn’t actually instrumentally incentivized.

So the specific temporal horizon required here varies according to how fast an AI can take over and make use of the acquired power. Generally, though, I expect many takeover plans to require a decent amount of patience in this respect.

Takeover-favoring incentives

Finally, even granted that these agential prerequisites and goal-content prerequisites are in place, rational takeover-seeking requires that the AI’s overall incentives favor pursuing takeover. That is, the AI needs to satisfy:

- Rationality of attempting take-over: the AI’s motivations, capabilities, and environmental constraints need to be such that it (rationally) chooses its favorite takeover plan over its favorite non-takeover plan (call its favorite non-takeover plan the “best benign alternative”).

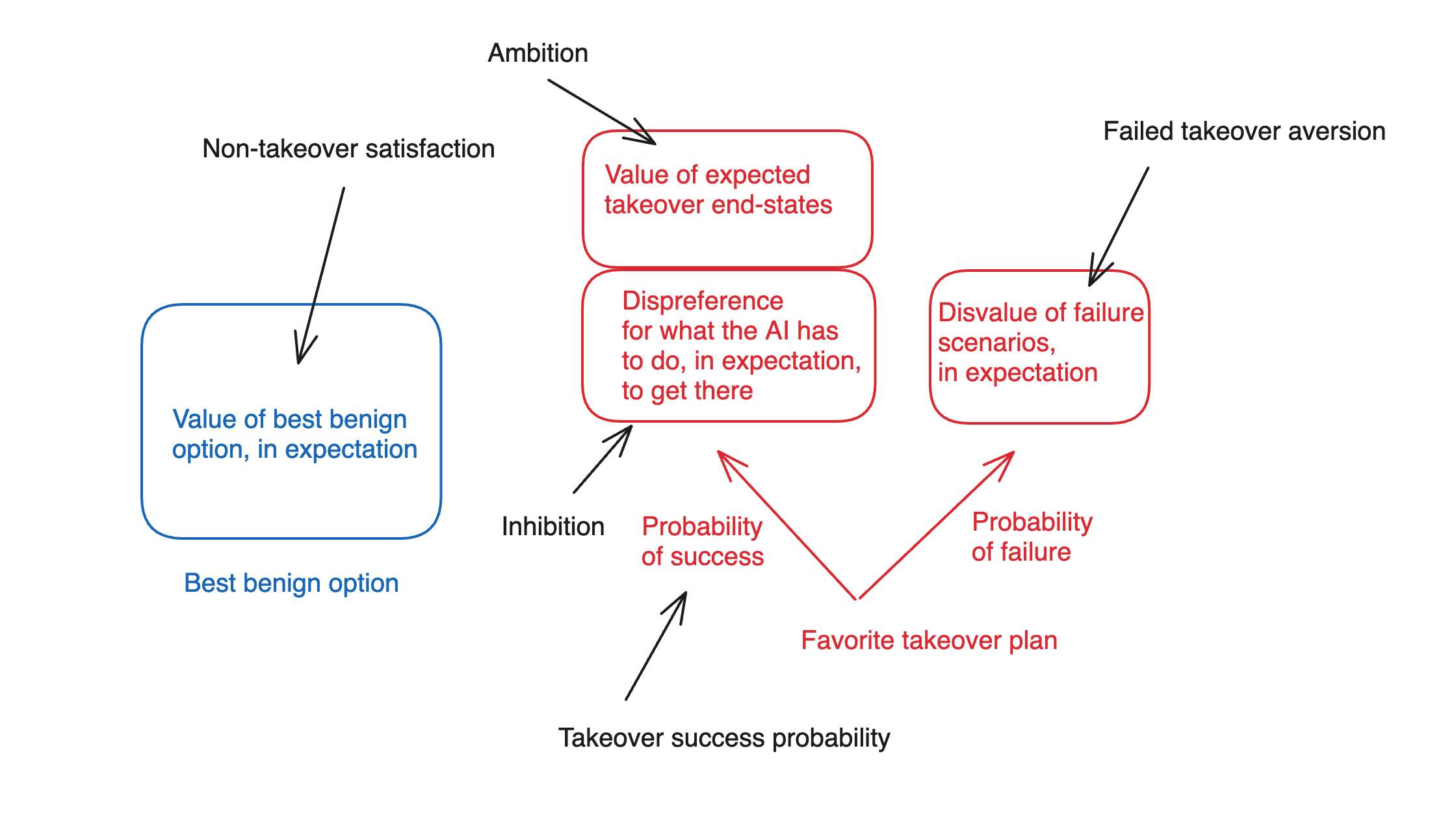

I think about the incentives at stake here in terms of five key factors:

- Non-takeover satisfaction: roughly, how much value the AI places on the best benign alternative.

- Note that we can try to actively increase an AI’s satisfaction, here – and we may have moral reasons to do so as well.

- Ambition: how much the AI values the expected end-state of having-taken-over, conditional on its favorite takeover plan being successful (but setting aside the AI’s attitudes towards what it has to do along the path to takeover).

- Note that this factor depends on what sorts of successful takeover worlds are actually on the table, with what probabilities.

- Thus, for example, if the world that the AI would be taking over would be damaged or defective in various ways, by the AI’s lights, then takeover might be less attractive. (This might be analogous to a case in which, in order to take over country A, country B would need to destroy all of country A’s citizenry, infrastructure, and resources.)

- And note also that to the extent that an AI needs to coordinate with other AIs with different values in order to take over, the expected amount of power/resources available for that AI’s values in particular, post-takeover, probably goes down.

- Note that this factor depends on what sorts of successful takeover worlds are actually on the table, with what probabilities.

- Inhibition: how much the AI disprefers various things it would need to do or cause, in expectation, along the path to achieving take-over, in the various success branches of its favorite take-over plan.

- Inhibitions, here, function in a manner roughly similar to “deontological constraints.” Thus, for example, maybe you’d prefer to have the money in that bank; but you won’t steal it due to an “inhibition” with respect to stealing. And the same can be true of AI systems.

- In principle we could also distinguish between “unendorsed” inhibitions, which an AI might remove or discard if it could, and “endorsed” inhibitions, where it would not. The former might be analogous to a phobia you judge irrational, and the latter might be analogous to an endorsed, deontological policy in favor of honesty. This distinction can matter in certain cases – but the thing that matters most here is the influence that the relevant inhibition exerts on the AI’s decision-making process in the relevant case.

- Take-over success probability: the AI’s estimated likelihood of successfully achieving take-over, if it pursued its favorite takeover plan.

- Failed-takeover aversion: how much the AI disprefers the worlds where it attempts its favorite takeover plan, but fails.

Thus, in a rough diagram:

A few notes on this breakdown.

- Here I am assuming that we can usefully understand the AI’s decision-making process using a roughly expected-value-like calculus. Again, we can query/relax this assumption if we like – but I think that classic arguments for misalignment risk are happy to grant it.

Beyond this, though, I am assuming that we can usefully decompose an AI’s attitudes towards its favorite takeover plan in terms of (a) its attitudes towards the expected end state of executing that plan, and (b) its attitudes towards the actions it would have to take, in expectation, along the way.[8] Admittedly, this is a somewhat janky composition – and if it irks you too much, you can just moosh them together into an overall attitude towards the successful takeover worlds. I wanted to include it, though, because I think “deontology-like prohibitions” on doing the sort of stuff an AI might need to do in order to takeover could well play in an important role in shaping an AI’s takeover-relevant incentives.[9]

Recasting the classic argument for AI risk using this framework

Why do I like this framework? A variety of reasons. But in particular, I think it allows for a productive recasting what I currently see as the classic argument for concern about AI existential risk – e.g., the sort of argument present (even if sometimes less-than-fully-explicitly-laid-out) in Bostrom (2014), and in much of the writing of Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Here’s the sort of recasting I have in mind:

- We will be building AIs that meet the agential prerequisites and the goal-content prerequisites.

We can make various arguments for this.[10] The most salient unifying theme, though, is something like “the agential prerequisites and goal-content prerequisites are part of what we will be trying to build in our AI systems.” Going through the prerequisites in somewhat more detail, though:

Agentic planning capability, planning-driven behavior, and adequate execution coherence are all part of what we will be looking for in AI systems that can autonomously perform tasks that require complicated planning and execution on plans. E.g., “plan a birthday party for my daughter,” “design and execute a new science experiment,” “do this week-long coding project,” “run this company,” and so on. Or put another way: good, smarter-than-human personal assistants would satisfy these conditions, and one thing we are trying to do with AIs is to make them good, smarter-than-human personal assistants.

Takeover-inclusive search falls out of the AI system being smarter enough to understand the paths to and benefits of takeover, and being sufficiently inclusive in its search over possible plans. Again, it seems like this is the default for effective, smarter-than-human agentic planners.

Consequentialism falls out of the fact that part of what we want, in the sort of artificial agentic planners I discussed above, is for them to produce certain kinds of outcomes in the world – e.g., a successful birthday party, a revealing science experiment, profit for a company, etc.

The argument for Adequate temporal horizon is somewhat hazier – partly because it’s unclear exactly what temporal horizon is required. The rough thought, though, is something like “we will be building our AI systems to perform consequentialist-like tasks over at-least-somewhat-long time horizons” (e.g., to make money over the next year), which means that their motivations will need to be keyed, at a minimum, to outcomes that span at least that time horizon.

I think this part is generally a weak point in the classic arguments. For example, the classic arguments often assume that the AI will end up caring about the entire temporal trajectory of the lightcone – but the argument above does not directly support that (unless we invoke the claim that humans will explicitly train AI systems to care about the entire temporal trajectory of the lightcone, which seems unclear.)

- Some of these AIs will be so capable that they will be able to take over the world very easily, with a very high probability of success, via a very wide variety of methods.

- The classic arguments typically focus, here, on a single superintelligent AI system, which is assumed to have gained a “decisive strategic advantage” (DSA) that allows a very high probability of successful takeover. In my post on first critical tries, I call this a “unilateral DSA” – and I’ll generally focus on it below.

- The dynamics at stake in scenarios in which an AI needs to coordinate with other AI systems in order to take over have received significantly less attention. This seems to me another important weak point in the classic arguments.

- The condition that easy takeover can occur via a wide variety of methods isn’t always stated explicitly, but it plays a role below in addressing “inhibitions” relevant to takeover-seeking, so I am including it explicitly here.

- As I’ll discuss below, I think this premise is in fact extremely key to the classic arguments – and that if we start to weaken it (for example, by making takeover harder for the AI, or only available via a narrower set of paths), the dynamics with respect to whether an AI’s incentives favor taking over become far less clear (and same for the dynamics with respect to instrumental convergence on problematic forms of power-seeking in general).

- I’ll also note that this premise is positing an extremely intense level of capability. Indeed, I suspect that many people’s skepticism re: worries about AI takeover stems, in significant part, from skepticism that these levels of capability will be in play – and that if they really conditioned on premise (2), and took seriously the vulnerability to AI motivations it implies, they would become much more worried.

- The classic arguments typically focus, here, on a single superintelligent AI system, which is assumed to have gained a “decisive strategic advantage” (DSA) that allows a very high probability of successful takeover. In my post on first critical tries, I call this a “unilateral DSA” – and I’ll generally focus on it below.

- Most motivational systems that satisfy the goal-content prerequisites (i.e., consequentialism and adequate temporal horizon) will be at least some amount ambitious relative to the best benign alternative. That is, relative to the best non-takeover option, they’ll see at least some additional value from the expected results of having successfully taken over, at least setting aside what they’d have to do to get there.

- Here the basic idea is something like: by hypothesis, the AI has at least some motivational focus on some outcome in the world (consequentialism) over the sort of temporal horizon within which takeover can take place (adequate temporal horizon). After successful takeover, the thought goes, this AI will likely be in a better position to promote this outcome, due to the increased power/freedom/control-over-its-environment that takeover grants. Thus, the AI’s motivations will give it at least some pull towards takeover, at least assuming that there is a path to takeover that doesn’t violate any of the AI’s “inhibitions.”

As an example of this type of reasoning in action, consider the case, in Bostrom (2014), of an AI tasked with making “at least one paperclip,” but which nevertheless takes over the world in order to check and recheck that it has completed this task, to make back-up paperclips, and so on.[11] Here, the task in question is not especially resource-hungry, but it is sufficiently consequentialist as to motivate takeover when takeover is sufficiently “free.”

- But the silliness of this example is, in my view, instructive with respect to just how “free” Bostrom is imagining takeover to be.

- Note, though, that even granted premises (1) and (2), it’s not actually clear the premise (3) follows. Here are a few of the issues left unaddressed.

- First: the question isn’t whether the AI places at least some value on some kind of takeover, assuming it can get that takeover without violating its inhibitions. Rather, the question is whether the AI places at least some value on the type of takeover that it is actually available.

- Thus, for example, maybe you’d place some value on being handed the keys to a peaceful, flourishing kingdom on a silver platter. But suppose that in the actual world, the only available paths to taking over this kingdom involves nuking it to smithereens. Even if you have no deontological prohibitions on killing/nuking, the thing you have a chance to take-over, here, isn’t a peaceful flourishing kingdom, but rather a nuclear wasteland. So our assessment of your “ambition” can’t focus on the idea of “takeover” in the abstract – we need to look at the specific form of takeover that’s actually in the offing.

- One option for responding to this sort of question is to revise premise (2) above to posit that the AI will be so powerful that it has many easy paths to favorable types of takeover. That is, that the AI would be able, if it wanted, to take over the analog of the peaceful flourishing kingdom, if it so chose. And perhaps so. But note that we are now expanding the hypothesized powers of the AI yet further.

- Second: the “consequentialism” and “adequate temporal horizon” conditions above only specify that some component of the AI’s motivation be focused on some consequence in the world over the relevant timescale. But the AI may have a variety of other motivations as well, which (even setting aside questions about its inhibitions) may draw it towards the best benign option even over the expected end results of successful takeover.

- Thus, for example, suppose that you care about two things – hanging out with your family over the next week, and making a single paperclip. And suppose that in order to take over the world and then use its resources to check and recheck that you’ve successfully made a single paperclip, you’d need to leave your family for a month-long campaign of hacking, nano-botting, and infrastructure construction.

- In this circumstance, it seems relatively easy for the best benign option of “stay home, hang with family, make a single paperclip but be slightly less sure about its existence” to beat the takeover option, even assuming you don’t need to violate any of your deontological prohibitions along the path to takeover. In particular: the other components of your motivational system can speak sufficiently strongly in favor of the best benign option.

- Again, we can posit that the AI will be so powerful that it can get all the good stuff from the best benign option in the takeover options as well (e.g., the analog of somehow taking-over while still hanging out with its family). But now we’re expanding premise (2) yet further.

- First: the question isn’t whether the AI places at least some value on some kind of takeover, assuming it can get that takeover without violating its inhibitions. Rather, the question is whether the AI places at least some value on the type of takeover that it is actually available.

And note, too, that arguments to the effect that “most motivational systems have blah property” quickly diminish in relevance once we are able to exert adequate selection pressure on the motivational system we actually get. Cf Ben Garfinkel on the fallacy of “most arrangements of car parts don’t form a working car, therefore this car probably won’t work.”[12]

Here the alignment concern is that we aren’t, actually, able to exert adequate selection pressure in this manner. But this, to me, seems like a notably open empirical question.

- Here the basic idea is something like: by hypothesis, the AI has at least some motivational focus on some outcome in the world (consequentialism) over the sort of temporal horizon within which takeover can take place (adequate temporal horizon). After successful takeover, the thought goes, this AI will likely be in a better position to promote this outcome, due to the increased power/freedom/control-over-its-environment that takeover grants. Thus, the AI’s motivations will give it at least some pull towards takeover, at least assuming that there is a path to takeover that doesn’t violate any of the AI’s “inhibitions.”

- Because of premise 2 (i.e., the AI can take over easily via a very wide variety of paths), the AI will be able to find a path to take over that is compatible with its inhibitions.

This essentially a version of what’s sometimes called the “nearest unblocked neighbor.” Here, the story is something like: suppose you successfully give the AI some quite hard constraint against “lying,” or against “killing humans,” or something like that. The idea is that the AI will be smart enough to find some way to take over that is still compatible with that constraint – e.g., only lying/killing in a way that doesn’t trigger its internal definition of “lying”/”killing.”[13] See e.g. Soares on “deep deceptiveness” as an example of this sort of story.[14]

There’s also a background constraint, here, which is that a useful AI can’t be too inhibited, otherwise it might not be able to function effectively to perform tasks for humans.

- There are also scenarios in which an AI’s motivations are such that its inhibitions about takeover get outweighed rather than routed around. E.g., the AI is sufficiently ambitious that it judges that otherwise-dispreferred actions like lying/killing are “worth it.” But I think the classic arguments focus more on “nearest unblocked neighbor” vibes.

- Because of premise (2), the AI’s probability of successful takeover, conditional on pursuing its favorite takeover plan, will be so high that we don’t even need to talk about its failed takeover aversion.

- That is, classic arguments rarely discuss the potential downsides, for the AI, of a failed takeover attempt, because they assume that takeover success, conditional on trying, is virtually guaranteed.

- Thus: the AI will rationally choose the takeover plan over the best benign option.

- This is meant to follow from all the premises above. That is:

- The agential prerequisites and the goal-content prerequisites will be satisfied (premise 1);

- The “takeover-favoring incentives” condition will be satisfied as well, because:

- the AI in question will see at least some benefit to successful takeover relative to the best benign option (premise 3);

- the AI’s inhibitions won’t stop it from pursuing takeover (premise 4);

- and the AI’s aversion to failed takeover won’t stop it either, because takeover is so likely to succeed (premise 5).

- This is meant to follow from all the premises above. That is:

What if the AI can’t take over so easily, or via so many different paths?

There’s a lot more to say about this broad sort of argument. For now, I mostly want to make one high level point: namely, that the argument as stated is loading very heavily on premise (2) – namely, that “Some of these AIs will be so capable that they will be able to take over the world very easily, with a very high probability of success, via a very wide variety of methods.” And indeed, if this premise is in fact correct, then the situation seems extremely scary.

If we weaken the premise even somewhat, however, note that the question of what sorts of motivational systems would lead to what sorts of takeover-favoring incentives becomes quite a bit more complicated. For example: if we instead say that the AI’s probability of success, if it attempts a takeover, is substantially less than ~100%, then we can no longer simply ignore the AI’s failed takeover aversion, or specify merely that it has some amount of ambition. Rather, we need to look in more detail at how bad it is, by the AI’s lights, if takeover fails; and relatedly, exactly how much it benefits, from successful takeover, relative to the best benign alternative.

- For example, if the “make a single paperclip” AI’s takeover efforts had had at least a 1% chance of getting it shut down and getting its single paperclip destroyed, then “take over the world in order to check and recheck that I have in fact made a single paperclip” would seem a less appealing strategy. And “can’t fetch the coffee if you’re not god emperor” suggests similar sorts of objections.

And similarly, if we assume that the AI does not, in fact, have an extremely wide variety of paths to takeover available, but rather can only take over via certain specific mechanisms like hacking data centers, lying to humans, etc, then it becomes less clear that the AI in question can just “route around” whatever inhibitions it has re: various paths to takeover. Or put another way: it becomes easier to “block” the relevant “neighbors.” Of course, in order to do this you need to be suitably able to give the AI system any inhibitions that might count against a given path towards takeover (e.g., inhibitions related to deception, harming humans, etc). But at least in certain cases, it seems possible that fairly imprecise degrees of motivational shaping (e.g., the type at stake in an AI’s negative reinforcement for paradigmatic forms of problematic behavior) would be adequate in this respect.

Indeed, I find it somewhat notable that high-level arguments for AI risk rarely attend in detail to the specific structure of an AI’s motivational system, or to the sorts of detailed trade-offs a not-yet-arbitrarily-powerful-AI might face in deciding whether to engage in a given sort of problematic power-seeking.[15] The argument, rather, tends to move quickly from abstract properties like “goal-directedness," "coherence," and “consequentialism,” to an invocation of “instrumental convergence,” to the assumption that of course the rational strategy for the AI will be to try to take over the world. But even for an AI system that estimates some reasonable probability of success at takeover if it goes for it, the strategic calculus may be substantially more complex. And part of why I like the framework above is that it highlights this complexity.

Of course, you can argue that in fact, it’s ultimately the extremely powerful AIs that we have to worry about – AIs who can, indeed, take over extremely easily via an extremely wide variety of routes; and thus, AIs to whom the re-casted classic argument above would still apply. But even if that’s true (I think it’s at least somewhat complicated – see footnote[16]), I think the strategic dynamics applicable to earlier-stage, somewhat-weaker AI agents matter crucially as well. In particular, I think that if we play our cards right, these earlier-stage, weaker AI agents may prove extremely useful for improving various factors in our civilization helpful for ensuring safety in later, more powerful AI systems (e.g., our alignment research, our control techniques, our cybersecurity, our general epistemics, possibly our coordination ability, etc). We ignore their incentives at our peril.

- ^

Importantly, not all takeover scenarios start with AI systems specifically aiming at takeover. Rather, AI systems might merely be seeking somewhat greater freedom, somewhat more resources, somewhat higher odds of survival, etc. Indeed, many forms of human power-seeking have this form. At some point, though, I expect takeover scenarios to involve AIs aiming at takeover directly. And note, too, that "rebellions," in human contexts, are often more all-or-nothing.

- ^

I’m leaving it open exactly what it takes to count as planning. But see section 2.1.2 here for more.

- ^

I’ll also generally treat the AI as making decisions via something roughly akin to expected value reasoning. Again, very far from obvious that this will be true; but it’s a framework that the classic model of AI risk shares.

- ^

Thanks to Ryan Greenblatt for discussion of this condition.

- ^

See my (2021).

- ^

Other components of an AI’s motivational system can be non-consequentialist.

- ^

There are some exotic scenarios where AIs with very short horizons of concern end up working on behalf of some other AI’s takeover due to uncertainty about whether they are being simulated and then near-term rewarded/punished based on whether they act to promote takeover in this way. But I think these are fairly non-central as well.

- ^

Note, though, that I’m not assuming that the interaction between (a) and (b), in determining the AI’s overall attitude towards the successful takeover worlds, is simple.

- ^

See, for example, the “rules” section of OpenAI model spec, which imposes various constraints on the model’s pursuit of general goals like “Benefit humanity” and “Reflect well on OpenAI.” Though of course, whether you can ensure that an AI’s actual motivations bear any deep relation to the contents of the model spec is another matter.

- ^

Though I actually think that Bostrom (2014) notably neglects some of the required argument here; and I think Yudkowsky sometimes does as well.

- ^

I don’t have the book with me, but I think the case is something like this.

- ^

Or at least, this is a counterargument argument I first heard from Ben Garfinkel. Unfortunately, at a glance, I’m not sure it’s available in any of his public content.

- ^

Discussions of deontology-like constraints in AI motivation systems also sometimes highlight the problem of how to ensure that AI systems also put such deontology-like constraints into successor systems that they design. In principle, this is another possible “unblocked neighbor” – e.g., maybe the AI has a constraint against killing itself, but it has no constraint against designing a new system that will do its killing for it.

- ^

Or see also Gillen and Barnett here.

- ^

I think my power-seeking report is somewhat guilty in this respect; I tried, in my report on scheming, to do better. EDIT: Also noting that various people have previously pushed back on the discourse surrounding "instrumental convergence," including the argument presented in my power-seeking report, for reasons in a similar vicinity to the ones presented in this post. See, for example, Garfinkel (2021), Gallow (2023), Thorstad (2023), Crawford (2023), and Barnett (2024); with some specific quotes in this comment. The relevance of an AI's specific cost-benefit analysis in motivating power-seeking was a part of my picture when I initially wrote the report -- see e.g. the quotes I cite here -- but the general pushback on this front (along with other discussions, pieces of content, and changes in orientation; e.g., e.g., Redwood Research's work on "control," Carl Shulman on the Dwarkesh Podcast, my generally increased interest in the usefulness of the labor of not-yet-fully-superintelligent AIs in improving humanity's prospects) has further clarified to me the importance of this aspect of the argument.

- ^

I’ve written, elsewhere, about the possibility of avoiding scenarios that involve AIs possessing decisive strategic advantages of this kind. In this respect, I’m more optimistic about avoiding “unilateral DSAs” than scenarios where sets of AIs-with-different-values can coordinate to take over.

Matthew_Barnett @ 2024-07-25T18:14 (+6)

I'm not sure I fully understand this framework, and thus I could easily have missed something here, especially in the section about "Takeover-favoring incentives". However, based on my limited understanding, this framework appears to miss the central argument for why I am personally not as worried about AI takeover risk as most EAs seem to be.

Here's a concise summary of my own argument for being less worried about takeover risk:

- There is a cost to violently taking over the world, in the sense of acquiring power unlawfully or destructively with the aim of controlling everything in the whole world, relative to the alternative of simply gaining power lawfully and peacefully, even for agents that don't share 'our' values.

- For example, as a simple alternative to taking over the world, an AI could advocate for the right to own their own labor and then try to accumulate wealth and power lawfully by selling their services to others, which would earn them the ability to purchase a gargantuan number of paperclips without much restraint.

- The expected cost of violent takeover is not obviously smaller than the benefits of violent takeover, given the existence of lawful alternatives to violent takeover. This is for two main reasons:

- In order to wage a war to take over the world, you generally need to pay costs fighting the war, and there is a strong motive for everyone else to fight back against you if you try, including other AIs who do not want you to take over the world (and this includes any AIs whose goals would be hindered by a violent takeover, not just those who are "aligned with humans"). Empirically, war is very costly and wasteful, and less efficient than compromise, trade, and diplomacy.

- Violently taking over the war is very risky, since the attempt could fail, and you could be totally shut down and penalized heavily if you lose. There are many ways that violent takeover plans could fail: your takeover plans could be exposed too early, you could also be caught trying to coordinate the plan with other AIs and other humans, and you could also just lose the war. Ordinary compromise, trade, and diplomacy generally seem like better strategies for agents that have at least some degree of risk-aversion.

- There isn't likely to be "one AI" that controls everything, nor will there likely be a strong motive for all the silicon-based minds to coordinate as a unified coalition against the biological-based minds, in the sense of acting as a single agentic AI against the biological people. Thus, future wars of world conquest (if they happen at all) will likely be along different lines than AI vs. human.

- For example, you could imagine a coalition of AIs and humans fighting a war against a separate coalition of AIs and humans, with the aim of establishing control over the world. In this war, the "line" here is not drawn cleanly between humans and AIs, but is instead drawn across a different line. As a result, it's difficult to call this an "AI takeover" scenario, rather than merely a really bad war.

- Nothing about this argument is intended to argue that AIs will be weaker than humans in aggregate, or individually. I am not claiming that AIs will be bad at coordinating or will be less intelligent than humans. I am also not saying that AIs won't be agentic or that they won't have goals or won't be consequentialists, or that they'll have the same values as humans. I'm also not talking about purely ethical constraints: I am referring to practical constraints and costs on the AI's behavior. The argument is purely about the incentives of violently taking over the world vs. the incentives to peacefully cooperate within a lawful regime, between both humans and other AIs.

A big counterargument to my argument seems well-summarized by this hypothetical statement (which is not an actual quote, to be clear): "if you live in a world filled with powerful agents that don't fully share your values, those agents will have a convergent instrumental incentive to violently take over the world from you". However, this argument proves too much.

We already live in a world where, if this statement was true, we would have observed way more violent takeover attempts than what we've actually observed historically.For example, I personally don't fully share values with almost all other humans on Earth (both because of my indexical preferences, and my divergent moral views) and yet the rest of the world has not yet violently disempowered me in any way that I can recognize.

Erich_Grunewald @ 2024-07-25T21:53 (+4)

I don't think you're wrong exactly, but AI takeover doesn't have to happen through a single violent event, or through a treacherous turn or whatever. All of your arguments also apply to the situation with H sapiens and H neanderthalensis, but those factors did not prevent the latter from going extinct largely due to the activities of the former:

- There was a cost to violence that humans did against neanderthals

- The cost of using violence was not obviously smaller than the benefits of using violence -- there was a strong motive for the neanderthals to fight back, and using violence risked escalation, whereas peaceful trade might have avoided those risks

- There was no one human that controlled everything; in fact, humans likely often fought against one another

- You allow for neanderthals to be less capable or coordinated than humans in this analogy, which they likely were in many ways

The fact that those considerations were not enough to prevent neanderthal extinction is one reason to think they are not enough to prevent AI takeover, although of course the analogy is not perfect or conclusive, and it's just one reason among several. A couple of relevant parallels include:

- If alignment is very hard, that could mean AIs compete with us over resources that we need to survive or flourish (e.g., land, energy, other natural resources), similar to how humans competed over resources with neanderthals

- The population of AIs may be far larger, and grow more rapidly, than the population of humans, similar to how human populations were likely larger and growing at a faster rate than those of neanderthals

Matthew_Barnett @ 2024-07-25T23:57 (+4)

I want to distinguish between two potential claims:

- When two distinct populations live alongside each other, sometimes the less intelligent population dies out as a result of competition and violence with the more intelligent population.

- When two distinct populations live alongside each other, by default, the more intelligent population generally develops convergent instrumental goals that lead to the extinction of the other population, unless the more intelligent population is value-aligned with the other population.

I think claim (1) is clearly true and is supported by your observation that Neanderthals' went extinct, but I intended to argue against claim (2) instead. (Although, separately, I think the evidence that Neanderthals' were less intelligent than homo sapiens is rather weak.)

Despite my comment above, I do not actually have much sympathy towards the claim that humans can't possibly go extinct, or that our species is definitely going to survive over the very long run in a relatively unmodified form, for the next billion years. (Indeed, perhaps like the Neanderthals, our best hope to survive in the long-run may come from merging with the AIs.)

It's possible you think claim (1) is sufficient in some sense to establish some important argument. For example, perhaps all you're intending to argue here is that AI is risky, which to be clear, I agree with.

On the other hand, I think that claim (2) accurately describes a popular view among EAs, albeit with some dispute over what counts as a "population" for the purpose of this argument, and what counts as "value-aligned". While important, claim (1) is simply much weaker than claim (2), and consequently implies fewer concrete policy prescriptions.

I think it is important to critically examine (2) even if we both concede that (1) is true.

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-07-25T20:37 (+4)

My read is that you can apply the framework two different ways:

- Say you're worried about any take-over-the-world actions, violent or not -- in which case this argument about the advantages of non-violent takeover is of scant comfort;

- Say you're only worried about violent take-over-the-world actions, in which case your argument fits into the framework under "non-takeover satisfaction": how good the AI feels about its best benign alternative action.

Matthew_Barnett @ 2024-07-26T00:28 (+2)

Say you're worried about any take-over-the-world actions, violent or not -- in which case this argument about the advantages of non-violent takeover is of scant comfort;

This is reasonable under the premise that you're worried about any AI takeovers, no matter whether they're violent or peaceful. But speaking personally, peaceful takeover scenarios where AIs just accumulate power—not by cheating us or by killing us via nanobots—but instead by lawfully beating humans fair and square and accumulating almost all the wealth over time, just seem much better than violent takeovers, and not very bad by themselves.

I admit the moral intuition here is not necessarily obvious. I concede that there are plausible scenarios in which AIs are completely peaceful and act within reasonable legal constraints, and yet the future ends up ~worthless. Perhaps the most obvious scenario is the "Disneyland without children" scenario where the AIs go on to create an intergalactic civilization, but in which no one (except perhaps the irrelevant humans still on Earth) is sentient.

But when I try to visualize the most likely futures, I don't tend to visualize a sea of unsentient optimizers tiling the galaxies. Instead, I tend to imagine a transition from sentient biological life to sentient artificial life, which continues to be every bit as cognitively rich, vibrant, and sophisticated as our current world—indeed, it could be even moreso, given what becomes possible at a higher technological and population level.

Worrying about non-violent takeover scenarios often seems to me to arise simply from discrimination against non-biological forms of life, or perhaps a more general fear of rapid technological change, rather than naturally falling out as a consequence of more robust moral intuitions.

Let me put it another way.

It is often conceded that it was good for humans to take over the world. Speaking broadly, we think this was good because we identify with humans and their aims. We belong to the "human" category of course; but more importantly, we think of ourselves as being part of what might be called the "human tribe", and therefore we sympathize with the pursuits and aims of the human species as a whole. But equally, we could identify as part of the "sapient tribe", which would include non-biological life as well as humans, and thus we could sympathize with the pursuits of AIs, whatever those may be. Under this framing, what reason is there to care much about a non-violent, peaceful AI takeover?

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-07-26T09:34 (+2)

I think that an eventual AI-driven ecosystem seems likely desirable. (Although possibly the natural conception of "agent" will be more like supersystems which include both humans and AI systems, at least for a period.)

But my alarm at nonviolent takeover persists, for a couple of reasons:

- A feeling that some AI-driven ecosystems may be preferable to others, and we should maybe take responsibility for which we're creating rather than just shrugging

- Some alarm that nonviolent takeover scenarios might still lead to catastrophic outcomes for humans

- e.g. "after nonviolently taking over, AI systems decide what to do humans, this stub part of the ecosystem; they conclude that they're using too many physical resources, and it would be better to (via legitimate means!) reduce their rights and then cull their numbers, leaving a small population living in something resembling a nature reserve"

- Perhaps my distaste at this outcome is born in part from loyalty to the human tribe? But I do think that some of it is born from more robust moral intuitions

Matthew_Barnett @ 2024-07-26T22:44 (+2)

I think I basically agree with you, and I am definitely not saying we should just shrug. We should instead try to shape the future positively, as best we can. However, I still feel like I'm not quite getting my point across. Here's one more attempt to explain what I mean.

Imagine if we achieved a technology that enabled us to build physical robots that were functionally identical to humans in every relevant sense, including their observable behavior, and their ability to experience happiness and pain in exactly the same way that ordinary humans do. However, there is just one difference between these humanoid robots and biological humans: they are made of silicon rather than carbon, and they look robotic, rather than biological.

In this scenario, it would certainly feel strange to me if someone were to suggest that we should be worried about a peaceful robot takeover, in which the humanoid robots collectively accumulate the vast majority of wealth in the world via lawful means.

By assumption, these humanoid robots are literally functionally identical to ordinary humans. As a result, I think we should have no intrinsic reason to disprefer them receiving a dominant share of the world's wealth, versus some other subset of human-like beings. This remains true even if the humanoid robots are literally "not human", and thus their peaceful takeover is equivalent to "human disempowerment" in a technical sense.

There ultimate reason why I think one should not worry about a peaceful robot takeover in this specific scenario is because I think these humanoid robots have essentially the same moral worth and right to choose as ordinary humans, and therefore we should respect their agency and autonomy just as much as we already do for ordinary humans. Since we normally let humans accumulate wealth and become powerful via lawful means, I think we should allow these humanoid robots to do the same. I hope you would agree with me here.

Now, generalizing slightly, I claim that to be rationally worried about a peaceful robot takeover in general, you should usually be able to identify a relevant moral difference between the scenario I have just outlined and the scenario that you're worried about. Here are some candidate moral differences that I personally don't find very compelling:

- In the humanoid robot scenario, there's no possible way the humanoid robots would ever end up killing the biological humans, since they are functionally identical to each other. In other words, biological humans aren't at risk of losing their rights and dying.

- My response: this doesn't seem true. Humans have committed genocide against other subsets of humanity based on arbitrary characteristics before. Therefore, I don't think we can rule out that the humanoid robots would commit genocide against the biological humans either, although I agree it seems very unlikely.

- In the humanoid robot scenario, the humanoid robots are guaranteed to have the same values as the biological humans, since they are functionally identical to biological humans.

- My response: this also doesn't seem guaranteed. Humans frequently have large disagreements in values with other subsets of humanity. For example, China as a group has different values than the United States as a group. This difference in values is even larger if you consider indexical preferences among the members of the group, which generally overlap very little.

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-07-26T23:19 (+6)

Since we normally let humans accumulate wealth and become powerful via lawful means, I think we should allow these humanoid robots to do the same. I hope you would agree with me here.

I agree with this -- and also agree with it for various non-humanoid AI systems.

However, I see this as less about rights for systems that may at some point exist, and more about our responsibilities as the creators of those systems.

Not entirely analogous, but: suppose we had a large creche of babies whom we had been told by an oracle would be extremely influential in the world. I think it would be appropriate for us to care more than normal about their upbringing (especially if for the sake of the example we assume that upbringing can meaningfully affect character).

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-07-25T10:16 (+2)

This is great. It's kind of wild that it's attracting downvotes.

Mjreard @ 2024-07-25T17:18 (+1)

The argument for Adequate temporal horizon is somewhat hazier

I read you suggesting we'd be explicit about the time horizons AIs would or should consider, but it seems to me we'd want them to think very flexibly about the value of what can be accomplished over different time horizons. I agree it'd be weird if we baked "over the whole lightcone" into all the goals we had, but I think we'd want smarter-than-us AIs to consider whether the coffee they could get us in 5 minutes and one second was potentially way better than the coffee they could get in five minutes, or they could make much more money in 13 months vs a year.

Less constrained decision-making seems more desirable here, especially if we can just have the AIs report the projected trade offs to us before they move to execution. We don't know our own utility functions that well and it's something we'd want AIs to help with, right?

SummaryBot @ 2024-07-25T14:33 (+1)

Executive summary: A framework for analyzing AI power-seeking highlights how classic arguments for AI risk rely heavily on the assumption that AIs will be able to easily take over the world, but relaxing this assumption reveals more complex strategic tradeoffs for AIs considering problematic power-seeking.

Key points:

- Prerequisites for rational AI takeover include agential capabilities, goal-content structure, and takeover-favoring incentives.

- Classic AI risk arguments assume AIs will meet agential and goal prerequisites, be extremely capable, and have incentives favoring takeover.

- If AIs cannot easily take over via many paths, the incentives for power-seeking become more complex and uncertain.

- Analyzing specific AI motivational structures and tradeoffs is important, not just abstract properties like goal-directedness.

- Strategic dynamics of earlier, weaker AIs matter for improving safety with later, more powerful systems.

- Framework helps recast and scrutinize key assumptions in classic AI risk arguments.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.