Lit review of some international organisations

By Forethought, rosehadshar @ 2026-02-10T08:19 (+9)

This is a linkpost to https://www.forethought.org/research/an-overview-of-some-international-organisations-with-their-voting-structures

This is a rough research note. It’s an informal literature review of voting structures in international organisations. I spent ~20 hours on it and am not a domain expert. A lot of the information comes from conversations with language models.

Summary

There’s a lot of scholarship on international orgs and their voting structures, in IR, political science, international law and probably other places.

The main structural options for international orgs are:

- Membership: size, heterogeneity

- Scope

- Vote distribution: unweighted / weighted

- Voting rule:

- Majority / supermajority / unanimity

- Normal majority rules / special majority rules

- Selective representation: cameralism, permanent seats, etc

The history of voting rules for international organisations is something like:

- Early period: unanimity voting

- 19th/early 20th century: international technical unions began to use majority voting

- After WW1: majority voting spread, international commodity organisations began to use weighted voting

- End of WW2: IMF and the World Bank set up with weighted voting, rest of the UN uses majority voting (with vetoes for the permanent seats on the Security Council)

- 1960s/70s: developing countries push against weighted voting and for bloc voting

- [I’m not sure if there are important trends after 1980]

Today, there are some patterns in voting rules:

| Voting rule | Used by | Strengths and weaknesses |

| Unanimity | Smaller orgs Security-related orgs

| Low risk of exploitation (so easier to get states to join) High compliance High decision costs (so slow to pass votes) |

| Majority | Most UN agencies The international courts Most human rights orgs | Low decision costs (so quick to pass votes) Higher risk of exploitation (so harder to get minority states to join) |

| Weighted | Development banks International commodity orgs | Easier to get powerful states to join Higher risk of exploitation for less powerful states Lower compliance |

Other interesting patterns:

- Level of democracy among founding members doesn’t correlate with voting rules

- Perceived legitimacy and problem-solving increase when orgs:

- Weighted voting seems pretty controversial

- Rules are often hacky and strange and seem the upshot of particular negotiations

- The strictest voting rules usually relate to hard power (money, security) or amendments

Here is a summary table of orgs by voting rule (spreadsheet version by individual org here). Some particularly interesting orgs:

- Intelsat: the US could have set up a communications satellite system unilaterally, but wanted the PR benefits of an international org, and was willing to trade some control for that.

- International Seabed Authority: set up to pre-empt conflict over deep sea mining once it became possible, but failed to get the US on board without weighted voting.

- ITER: recent organisation including the US, China, Russia, India, and EU to develop fusion technology. Uses weighted voting, and the EU has substantially more votes than any other individual member (45% to 10%). Has a unanimity rule for many issues.

General analysis

Who knows about this?

There’s lots of scholarship, and I haven’t reviewed it properly. Here are some fields and keywords, with the articles that I did read:

- International law

- Zamora (1980)

- Posner and Sykes (2014) - law and economics

- Political science

- Blake and Payton (2014) - institutional design

- IR

- Koremos, Lipson and Snidal (2001) - rational design

- Panke, Polat and Hohlstein (2022) - comparative politics, legitimacy studies

What are the main structural options?

Here is my own summary of the main structural options:

- Membership: size, heterogeneity

- Scope

- Vote distribution: unweighted / weighted

- Voting rule:

- Majority / supermajority / unanimity

- Normal majority rules / special majority rules

- Selective representation: cameralism, permanent seats, etc

Below are summaries from other people.

Posner and Sykes (2014) “identify several different dimensions[:]

- One-vote-per-state versus weighted voting where different states have a different number of votes.

- The strength of the voting rule, ranging from majority rule, through various supermajority rules, to consensus.

- Cameralism, or the clustering of states with similar interests into different bodies that must separately approve a resolution.

- Variation in the scope of the authority of the voting body—regarding whether it can make a legally binding decision or not, and the importance of the decision that it is permitted to make.

- Different voting rules or procedures for different types of decisions—procedural versus substantive, for example.”[1]

Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal (2001) break down international institution design into five main dimensions:

- Membership (exclusive or inclusive, regional or universal, states only or NGOs too)

- Scope of the issues covered

- Centralization, including to disseminate information, to reduce bargaining and transaction costs, and to enhance enforcement

- Control, of which voting structure is one important aspect

- Flexibility, including adaptive and transformative

Blake and Payton (2015) and Zamora (1980) give the following main voting rules:

| Voting rule | Vote distribution | Veto power | Intellectual roots |

| Unanimity | Equal | Universal | Traditional international law[2] |

| Majoritarian | Equal | Limited | Democratic philosophy |

| Weighted | Unequal | Uneven | European great power diplomacy |

Posner and Sykes (2014) note that “One can also pick a rule between majority and unanimity—a supermajority rule of 3/5, 4/5, or whatever. As the supermajority required by a voting rule increases, the decision costs increase as well (because more states must agree) but the exploitation costs decline (because fewer states can be outvoted).”[3]

Zamora (1980) gives the following (non-exclusive) ways to recognise inequality of states in voting procedures:[4]

| Approach | Options to consider |

| Weighted voting | Criteria Degree of weighting (i.e. basic votes) |

| Majority requirements | Normal majority requirements Special majorities[5]

|

| Selective representation on executive organs | Election in proportion to weighted votes

Permanent seats Fixed blocs to elect from |

What patterns do we see?

Historically

Early international organisations used unanimity voting.[6]

- It was believed that international decisions couldn’t be imposed on states against their will without that violating their sovereignty

International technical unions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries began to use majoritarian voting.[7]

- Unanimity voting wasn’t practical

- The scope and authority was limited, so states were willing to cede veto powers

- They tended to be manned by technical experts, who were more willing to accept majority decisions than diplomats

After WW1, international organisations became more common.[8] Majority voting spread, and international commodity organisations began to use weighted voting.[9]

- The League had unanimity but not for all issues; the ILO had majority rule

- International commodity organisations were suited to weighted voting because they had:

- Narrow functions

- Easily defined criteria for weighting (exports and imports)

At the end of WW2, international organisations became more common still.[10] The Bretton Woods Conference set up the IMF and the World Bank using weighted voting. The rest of the UN was mostly based on majority voting (with vetoes for the permanent seats on the Security Council).

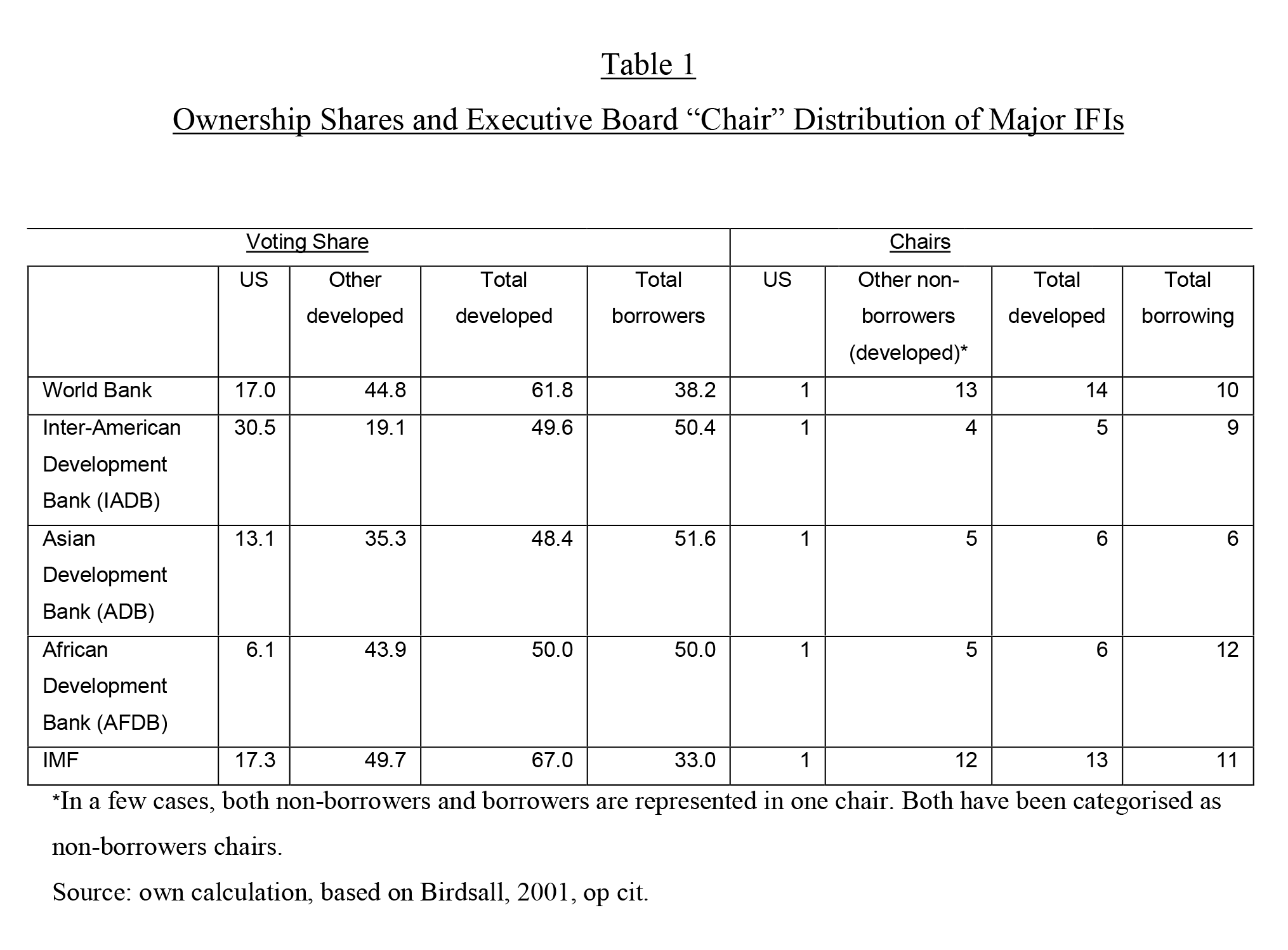

- Most international lending institutions outside the UN also use weighted voting.[11]

- UN agencies tended to favour special majorities over weighted voting as a safeguard, for political reasons.[12]

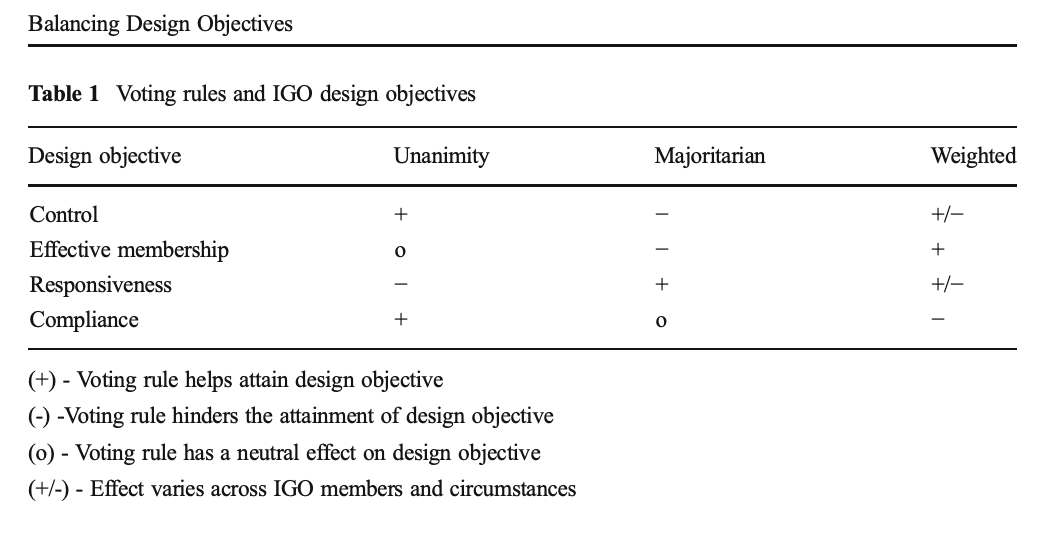

In the period after WW2, around 45% of IGOs used majority voting, 35% unanimity voting, and 20% weighted voting.[13]

- (Note that this hides lots of complexity: organisations often have different rules for different bodies and different issues.)[14]

In the 1960s and 1970s, developing countries began to push against weighted voting, and for formalised block voting.[15]

- UNCTAD was set up in 1964 as an alternative to GATT, and is the first organisation to use formalised political (rather than functional) bloc voting.

- Some developing countries still supported weighted voting in the international development banks and international commodity agreements though.

I’m not sure if there are important trends after 1980 (as that’s when my source for this history was written).

Today

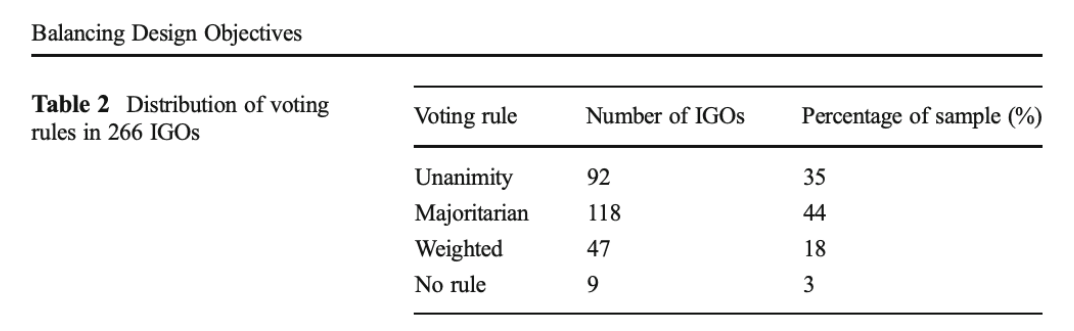

In their dataset of ~300 IGOs founded between 1944 and 2005,[16] Blake and Payton (2015) find that:

- Unanimity voting: smaller orgs and security-related orgs are more likely to use unanimity voting.

- Democracy: The level of democracy among founding members does not have a significant impact on the choice of voting rules.

We also see some other empirical patterns:

- Weighted voting: international commodity orgs,[17] development banks[18]

- Majority voting: most UN agencies,[19] international courts,[20] most human rights orgs[21]

Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal (2001) argue that variation in governance structure can be explained by:

- Distribution problems

- Enforcement problems

- Number of actors involved

- Uncertainty about behaviour, state of the world, and preferences

Posner and Sykes (2014) “identify the following factors as playing a role in the determination of voting rules:

- decision costs;

- exploitation costs;

- heterogeneity (meaning that some states gain more from collective decisions than others or lose more from adverse decisions than others); and

- discount factors (which of course can be heterogeneous as well).”[22]

They predict that:[23]

- More homogeneous groups will tend to have weaker voting rules.

- States with higher discount factors will have weaker voting rules.

- These states will tend to be richer states.

- So “organizations involving only rich states will have weaker voting rules than organizations involving poor states or a mix of rich and poor states.”

Zamora (1980) makes the following claims, but I’m not sure if they are still true (the article is good, but old and non-quantitative):

- Recommendatory economic organisations tend to have simple voting procedures and limited decision making outside formal votes.[24]

- Task-oriented economic organisations have more formal voting safeguards (to ensure the support of influential members), and use informal routes more (for efficiency).[25]

- But this requires high goal consensus.[26]

- “Most organizations require a simple majority of the membership to establish a quorum and a simple majority of the votes cast to make most decisions. However, the more important the purpose of the organization, the higher the normal majority requirement, with political and economic organizations generally having the highest normal majority requirements.”[27]

- Weighted voting orgs tend to have more and higher special majority decisions.[28]

- “The most efficient agencies are the least democratic [i.e. use weighted voting], yet they are also the organizations that operate with the highest degree of consensus.”[29]

- They have well-defined functions which don’t threaten individual members.

- There are objective criteria for decisions which reduces conflict.

- They have highly competent secretariats.

What do we know about the strengths and weaknesses of different structures?

From theory

| Voting rule | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Unanimity | Low risk of exploitation (so easier to get states to join)[30] High compliance[31] | High decision costs (so slow to pass votes)[32] |

| Majority | Low decision costs (so quick to pass votes)[33] | Higher risk of exploitation (so harder to get minority states to join)[34] |

| Weighted | Easier to get powerful states to join[35] | Higher risk of exploitation for less powerful states[36] Lower compliance[37] |

In short:

- It’s easy to get people to agree to unanimity voting, but hard to do anything with it

- It’s easy to do things with majority voting, but hard to get (powerful) people to agree to it

- Powerful states like weighted voting

See also this appendix.

From empirical studies

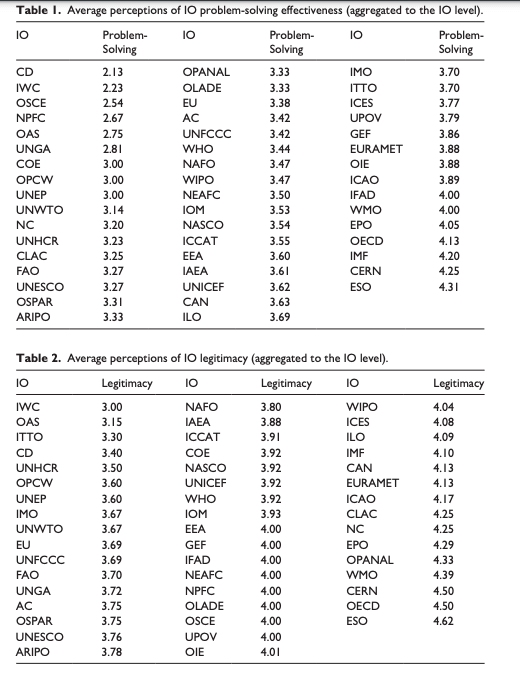

A survey of people working at IOs found that:[38]

- Perceived legitimacy increases with:

- Regional (over global) membership

- Non-state actor access

- Deliberative diplomatic practices

- Perceived problem-solving increases with:

- Regional (over global) membership

- Autonomous secretariats

- Deliberative diplomatic practices

- Perceived problem-solving decreases with:

- Consensus decision-making rules

Particular organisations

Summary table

Note that:

- Organisations with weighted voting may have either majority or supermajority rules. I’ve put notable rules in brackets

- Many organisations have different rules for different bodies/kinds of vote. Where I haven’t specified, this is the ‘normal’ rule in the main body of the organisation

- I’ve marked organisations with permanent seats with an ‘✢’ and those with cameralism with an ‘⁑’

- There’s a summary table by organisation here

- I’m not using precise definitions or selection criteria, and instead am pragmatically looking at examples which seemed relevant

| Weighted | Majority | Supermajority | Unanimity | |

| Orgs covered below | World Bank (criteria: share of capital stock; normal rule: majority; special majorities for amendments, increasing capital stock, issuing shares; unanimity for withdrawal) Intelsat (criteria: usage; rules: US+12.5-8.5% for substantive decisions under interim agreements; ⅔ for substantive decisions under definitive agreements) IMF (criteria: SDRs; rules: 70% for investments, 85% for amendments and quota changes) ITER (criteria: ITER contributions; special rules: unanimity for adopting the weighted voting system and the rules of procedure, electing the Director-General, budget, changes to cost sharing, new members, amendments, and various other things) | UN General Assembly GATT WHO CERN IAEA ⁑ UNCTAD ⁑ International Seabed Authority Council and Assembly (procedural) WTO GAVI

| ✢ UN Security Council (9/15, plus unanimity among the permanent seats) GATT (⅔, to amend articles) WHO (⅔ for amendments, appointing the Director-General, budget decisions, suspending members, and other important decisions) IAEA (Conference: ⅔ for finances, amendments, suspension; Board: ⅔ for budget, election of Director General, reconsidering rejected amendments) ⁑ International Seabed Authority Council (⅔ and a majority of each chamber) WTO (⅔ for new members, ¾ for waivers and interpretations of obligations) Council of the EU, Treaty of Lisbon (qualified majority: 55%-72% of members, representing 65% of the EU population) | GATT (basic rules) NATO OECD IPCC ⁑ International Seabed Authority Council (for benefit distribution) Council of the EU, Treaty of Lisbon (for security, tax)

|

| In general | International commodity organisations (criteria: imports/exports, rule: super/majority with cameralism)[39] International development banks (criteria: contributions)[40] | International technical unions[41] Most UN agencies[42] International courts[43] Human rights organisations[44] [Weaker voting rules] Richer states, more homogenous states, states with higher discount factors[45] | Political and economic orgs (?)[46] Weighted voting orgs (?)[47] European bodies[48] [Stricter voting rules] Poorer states, less homogenous states, states with lower discount factors[49] | Smaller orgs[50] Security orgs[51] |

| Misc other orgs | EEC Council of Ministers (criteria: negotiated)[52] Council of the EU, Treaty of Nice (criteria: negotiated; rule: qualified majority)[53] | ICJ, ICC, ILO, ICJ, ICC ✢ League of Nations Council (normal rule, but rarely applicable)[54] | League of Arab States, COMECON, EFTA, Council of Europe ✢ League of Nations Council (most issues) |

Points of interest

Weighted voting seems pretty controversial

- Tentatively I do think weighted voting would be a feasible mechanism between ~Western allies

- Mostly seems to be developing nations opposing weighted voting

- Controversy around World Bank, IMF

- It sounds as though in 1994 the International Seabed Authority (which includes developing nations) a) wouldn’t agree to weighted voting, b) consequently lost the US as a member

- The UK and the Netherlands have both joined weighted voting orgs in the recent past, including ones where they don’t have tonnes of voting power

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), founded in 2016, which uses weighted voting based on contributions. 100 members including China but not the US, Netherlands has around 1% of the votes, UK around 3%

- Netherlands also a member of the European Stability Mechanism (2012), which uses weighted voting based on contributions

- Mostly seems to be developing nations opposing weighted voting

- Most likely ways I could be wrong about this:

- Weighted voting is acceptable specifically in the context of lending institutions

- Weighted voting is acceptable specifically in the context of orgs where members make substantial financial contributions

- An AI joint project would probably meet this condition, but might not

Rules are often hacky and strange and seem the upshot of particular negotiations

- Council of the EU (Treaty of Nice): weighted, and the weights were just negotiated rather than based on objective criteria

- International Seabed Authority: complicated system with four different blocs that need to be represented in the Council and which must all vote in favour for something to pass. Landlocked nations must be represented

- Security Council: veto at the insistence of permanent members, supermajority at insistence of everyone else

- Intelsat: important matters require 12.5% of votes in addition to US votes (requiring at least some European backing), but this drops to 8.5% after 60 days (not requiring any European backing)

The strictest voting rules usually relate to hard power (money, security) or amendments

- Money and security:

- International Seabed Authority: unanimity for distributing benefits

- IMF: 70% for investment decisions, 85% for quota changes

- NATO: unanimity

- Council of the EU (Treaty of Lisbon): unanimity for tax and security

- UN Security Council

- Amendments: IMF 85%, WTO 75%, WHO ⅔

Intelsat is pretty interesting

- The US could have set up a communications satellite system unilaterally, but wanted the PR benefits of an international org, and was willing to trade some control for that.

The International Seabed Authority is pretty interesting

- Set up to pre-empt conflict over deep sea mining once it became possible, but failed to get the US on board without weighted voting.

ITER is pretty interesting

- Recent organisations including the US, China, Russia, India, and EU to develop a new technology. Uses weighted voting, and the EU has substantially more votes than any other individual member (45% to 10%). Has a unanimity rule for many issues.

Organisations

Note that:

- These are arranged in rough chronological order.

- With the exception of GAVI, they are all regular international organisations

- I didn’t include the Manhattan Project, as understanding its decision making seemed like a large undertaking

- I cover basic voting rules for all orgs. I also include (sometimes very) brief notes on:

- Strengths and weaknesses, for the World Bank, IMF, UN General Assembly, UN Security Council, CERN, IAEA, OECD, IPCC, WTO

- Why those rules were chosen, for UN General Assembly, UN Security Council, GATT, CERN, Intelsat, UNCTAD, International Seabed Authority, WTO

World Bank[55]

Made up of several organisations:

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) - 1944

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) - 1956

- International Development Association (IDA) - 1960

- Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) - 1988

Date(s): 1944 and later

Membership: global

Scope: Lending organisation

- IBRD: Provides loans and financial advice to middle-income countries for development projects.

- IFC: Invests in private enterprises in developing countries to stimulate economic growth.

- IDA: Offers interest-free loans and grants to the poorest countries, supporting social and economic programs.

- MIGA: Issues guarantees against non-commercial risks to encourage foreign investment in developing countries.

Distribution: weighted, with basic votes (IBRD, IFC: ~5% of total votes; IDA: ‘membership votes’; MIGA: parity votes such that developed and developing countries have equal votes overall)[56]

Weight criteria: share of Bank (IBRD)/IFC/MIGA capital, or contributions to IDA replenishments

Normal rule: majority

Special rules:

- IRBD: 85% for amendments, 80% for increasing the number of Directors, 75% for increasing capital stock, unanimity for withdrawal[57]

- IFC: 85% for increases in capital stock, 75% for issuing shares, ⅗ and 85% of voting power for amendments, unanimity for withdrawal[58]

- IDA: ⅔ for increasing subscriptions, ⅗ of members holding ⅘ of voting power for amendments, unanimity for withdrawal[59]

- MIGA: ⅔ and 55% of shares for amendments and various other things[60]

Informal rules: formal votes are rare

Selective representation:

- Directors get certain share of the vote regardless of what share they were elected by[61]

- Directors cannot split their votes[62]

Notes

- Bretton Woods. Very similar to the IMF. actually made up of many bodies

- Developing countries complain they are underrepresented and that lending favours nations who are friendly with creditors and comes with counterproductive conditions[63]

- “[I]n the World Bank, voting power is aligned to ownership shares. At its founding, when ownership shares were closely related to financial contributions, this made sense. Today, however some major shareholders, especially the United States exercise influence that is out of proportion to their current costs”[64]

IMF[65]

Date(s): 1944

Membership: global

Scope: Provides loans to countries in economic distress and advises on macroeconomic policies

Distribution: weighted, with basic votes (~5% of total votes)

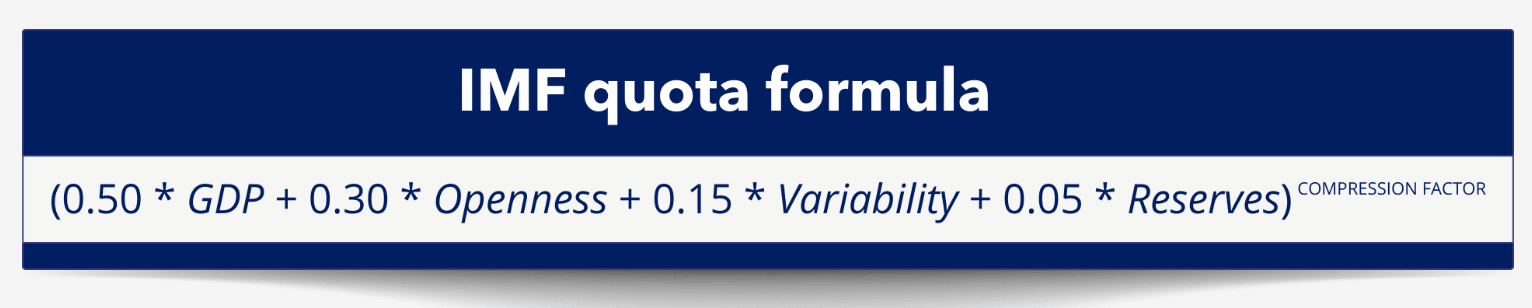

Weight criteria: special drawing rights (SDRs, a reserve currency created by the IMF), which are based on quotas, which are based on a formula to measure the size of the member’s economy:[66]

is a blend of 60 percent GDP at market rates and 40 percent at PPP exchange rates. is the sum of annual current payments and current receipts on goods, services, income, and transfers. is the standard deviation of current receipts and net capital flows. are twelve-month running averages of FX and gold reserves. And is a compression factor set to be 0.95 to reduce the dispersion of the results.

Rules:

- 70% for investment decisions

- 85% for amendments and quota changes

- Note the US has an effective veto here, and is the only country to do so

Informal rules:

- Formal votes are rarely taken on the Executive Board, which strives for consensus

Selective representation:

- Large members have their own executive director. Small members band together to elect directors. Each director has votes equal to the votes of the countries they represent.

Notes

- Developing countries complain they are underrepresented and so conditionality is too restrictive and borrowers don’t get as much benefit as they should

- (Here is an interesting blog on this; changes are currently blocked because of the 85% requirement. Currently, China and Europe have too few votes and the US has too many.)

UN General Assembly[67]

Date(s): 1945

Membership: global

Scope: Passes non-binding resolutions, approves the UN budget, elects 10/15 security council members and all ICJ members

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: majority

Notes

- Decision-making is easy

- The majority often outvote the minority of powerful states

- Anticipating this, powerful states made sure resolutions would be non-binding

UN Security Council

Date(s): 1945

Membership: 10 rotating seats, plus permanent seats for US, Russia, China, UK, France

Scope: Issues binding resolutions on security for all UN states

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: 9/15 majority, and unanimity among permanent members

Selective representation: permanent seats for US, Russia, China, France, UK

Notes

- Powerful countries insisted on a veto

- Small countries insisted on a high supermajority, so that multiple rotating votes would be required

- The result is a very strict voting rule, and gridlock by default

GATT[68]

Date(s): 1947-1995

Membership: global

Scope: Forum for negotiating tariff reductions and resolving trade disputes

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: majority

Special rules:

- Unanimity for basic rules

- ⅔ to amend other articles

Notes

- ITO never gets off the ground as votes aren’t weighted in favour of Western powers

- GATT is a part of the ITO charter and does survive

- Western powers joined even though it had an unweighted voting structure, because:[69]

- It was mostly a negotiating forum

- Withdrawal was easy

WHO

Date(s): 1948

Membership: global

Scope: Coordinates international health responses, sets global health standards, and provides technical support to countries

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: majority

Special rules: ⅔ for amendments, appointing the Director-General, budget decisions, suspending members, and other important decisions

NATO

Date(s): 1949

Membership: 31 North American/European countries

Scope: Military alliance for collective defence of North American and European members

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: unanimity[70]

Notes

- Member countries voluntarily provide military forces and capabilities, and cover the costs of deploying their own troops.

- Financial contributions to the common budget are made according to a cost-sharing formula based on Gross National Income.

CERN

Date(s): 1954

Membership: 23 mostly European states

Scope: Operates large-scale particle accelerators and detectors to conduct fundamental physics research

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: majority (aims for consensus)

Notes

- External observers pushed for weighted voting, and using unweighted was controversial[71]

- See [Final] CERN Case Study, Maas and Villalobos (2023) and Hausenloy and Dennis (2023) for strengths and weaknesses.

IAEA[72]

Date(s): 1946

Membership: global

Scope: Inspects nuclear facilities, provides technical assistance, and sets safety standards for nuclear energy use

Structure:

- General Conference of all member states

- 35 member Board of Governors

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: majority

Special rules:

- General Conference: ⅔ for finances, amendments, suspension[73]

- Board: ⅔ for budget, election of Director General, reconsidering rejected amendments[74]

Selective representation: Board of governors has 13 seats for nations with advanced atomic tech, and 22 are elected by the general conference

Notes

- Description

- “The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was founded in 1957 to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and limit its use for military purposes. The IAEA exists as an autonomous organization within the United Nations. In practice, one of its main purposes is to verify that states do not build nuclear weapons.

- The IAEA can conduct inspections to ensure that states are not secretly building nuclear facilities. Findings from inspections are reported to the IAEA Board of Directors. If the Board of Directors believes that a state is not complying with international agreements, the Board can escalate the issue to the UN Security Council.

- Ultimately, the IAEA does not have the authority to take action directly– it simply provides information to the UN Security Council and member states.”[75]

- Strengths:[76]

- Proven success in governing nuclear technology for over 50 years

- Established verification mechanisms for compliance

- Some analogies to AI, such as monitoring hardware (like uranium in nuclear)

- Success in limiting proliferation while enabling beneficial development

- Ability to inspect systems, require audits, test for compliance with safety standards, and place restrictions on deployment and security levels[77]

- Weaknesses as an analogy for AI:

- AI is harder to verify, audit and safeguard than nuclear materials

- The IAEA moved more slowly than would be necessary for AI

- The actors involved are different for AI

- The intense level of oversight provided by the IAEA might be prohibitively difficult to negotiate for AI.[86]

OECD

Date(s): 1961

Membership: 38 developed countries

Scope: Collects data, conducts analyses, and issues policy recommendations to promote economic growth and social well-being

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: unanimity[87]

Notes

- Able to move quickly on policy-setting because its membership is mostly aligned[88]

Intelsat

See Intelsat as a Model for International AGI Governance for more detail.

Date(s): 1964-2001

Membership: global (initially ~Western powers, excluding USSR)

Scope: Set up and managed the global satellite communications system

Structure:

- Interim agreements (1964-1973)

- ISCS (executive)

- Comsat (manager)

- Definitive agreements (1973-2001)

- Assembly of parties (treaty changes)

- Meeting of signatories (approves board)

- Board of governors (manager)

Distribution: weighted, apart from the Assembly of Parties which was unweighted

Weight criteria: usage

- Interim agreements: international telephone traffic and domestic traffic above 2000 km (Lipscy)

- Definitive agreements: usage of the Intelsat system

Rules:

- Interim agreements:

- Unanimity, or failing that, US+12.5% for 14 key decisions

- Decisions: types of space segment, standards for earth stations, budget, adjusting accounts, establishing rates, additional contributions, placing contracts, satellite launches, quotas, withdrawal, amendments, adopting rules of procedure, compensating Comsat[89]

- Meant some European votes would be required

- Though note that the UK had successfully pushed for freedom for European countries to not vote in a bloc[90]

- After 60 days, US+8.5%, for a subset of key decisions

- Majority for procedural issues (Codding, p. 27)

- Unanimity, or failing that, US+12.5% for 14 key decisions

- Definitive agreements:

- Assembly: 2/3 of states plus 2/3 investment or 85% of membership (Codding)

- Meeting of Signatories: majority for procedural, 2/3 for substantive (Codding)

- Board of Governors:[93]

- Simple majority for procedural matters

- 2/3 majority of voting participation or total Board minus 3 for substantive matters

- 2/3 majority to overrule the Chairman on procedural vs substantive determinations

Informal rules:

- Interim agreements: most decisions decided without a vote (Codding, p. 27)

Selective representation:

- Interim agreements: new members max 17%, with all other members' shares decreasing proportionally (which meant the US would always have a minimum of 50.5%) (Lipscy)

- Definitive agreements: US limited to 40% regardless of usage (Levy)

Notes

- Intelsat is an interesting model for AGI governance because:

- It was a successful multilateral project to build a primarily commercial technology of geopolitical importance.

- It was US-led, with the US retaining control, but with meaningful oversight from allies.

- It provided major benefits to both the US and its allies, compared to the US going alone.

- It was set up quickly, under interim agreements with an initially small number of close allies, with scope for flexibility long-term.

- It is a successful example of differential technological progress, and led to a system which was strategically more beneficial to the US than would otherwise have arisen.

- Disanalogies with AGI don’t seem to undermine this:

- The US needs allies even more for the development of AGI than it did for satellite communications.

- The USG was more involved in the development of satellite communications technology than it has been so far in AGI development. But if scaling continues, this might need to change in order to reach AGI.

UNCTAD[94]

Date(s): 1964

Membership: global

Scope: Development-friendly economic forum (set up as an alternative to GATT)

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: super/majority within formalised blocs[95]

Informal rules:

- Formal conciliation procedure to arrive at common position before a vote

- In fact never used, and informal consensus reached between blocs

Notes

- Set up by developing countries as a GATT alternative

- First formalised political bloc voting[96]

IPCC

Date(s): 1988

Membership: global

Scope: Assesses climate change science to inform policymakers

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: consensus[97]

Notes

- See Hausenloy and Dennis (2023) for strengths and weaknesses.

International Seabed Authority[98]

Date(s): 1994

Membership: global, but not the US[99]

Scope: Regulates and issues licences for deep sea mining

Structure:

- Council issues regulations and licences and proposes the budget

- Assembly sets policy, approves the budget and distributes benefits

Distribution: unweighted[100]

Rules:

- Assembly: majority for procedural, ⅔ for substantive

- Council: majority for procedural, ⅔ and the majority of each chamber for substantive, unanimity for distribution of benefits[101]

- “Effectively, this means that all decisions require a majority or tie vote in each chamber, plus two-thirds of all members in the aggregate.”[102]

Selective representation:

- Council: 4 chambers:

- 4x largest consumers of minerals like those in the seabed

- 4x largest investors in deepsea mining

- 4x exporters of minerals like those in the seabed (min 2x developing)

- 24x developing states (inc 6x with special interests like being large or land-locked)

Notes

- Set up by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

- Deep sea mining wasn’t yet possible, but they wanted to prevent conflict and over extraction

- The plan was to generate earn royalties by licensing companies, and redistribute that to members

- 1994 agreement introduces cameralism, but the US wanted weighted voting and refused join[103]

WTO[104]

Date(s): 1995

Membership: global

Scope: Regulates international trade

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: consensus, or failing that majority rule

Special rules:

- ¾ for waivers and interpretations of obligations

- ⅔ for new members, but no member needs to extend its obligations to a new member without consent

- Any amendment to obligations is non-binding on members

- In arbitration (which are settled by majority rule on a panel), final decisions are automatically adopted by all members unless there is reverse consensus against the decision

Notes

- “Holdout issues were significant, and some GATT members balked at some of the proposed new commitments. In response, the major players agreed on a novel strategy – they would formally withdraw from the GATT, and enter a new treaty creating the WTO. Any GATT member who wished to retain the benefits of GATT membership in relation to the major players had to do the same even if they did not like aspects of the new WTO regime. Some members complained that the process was coercive, but they had little choice but to capitulate.”[105]

- It’s very hard to add or modify commitments

- There are side agreements which only bind the members who sign them, and separate free trade agreements (e.g. NAFTA, TPP)

ITER[106]

Date(s): 2007

Membership: China, EU, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and USA

Scope: Constructs and operates an experimental fusion reactor to demonstrate fusion's viability as an energy source

Distribution: weighted

Weight criteria: ITER contributions[107]

- Europe: 45.6%

- China, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, US: 9.1% each

Rules:

- Outlined in the Council’s rules of procedure, which unfortunately I can’t find

- Unanimity required for adopting the weighted voting system and the rules of procedure, electing the Director-General, budget, changes to cost sharing, new members, amendments, and various other things

GAVI

Date(s): 2000

Membership: diverse PPP

Scope: PPP to improve vaccine access

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: consensus, or majority failing that

Selective representation: developing countries have 5 seats, donor countries have 5 seats, civil society has 1 seat, vaccine industry has 1 seat, research institutes have 1 seat.

Council of the EU (Treaty of Lisbon)[108]

Date(s): 2014 (transition period to 2017)

Membership: EU

Scope: Negotiates and adopts EU laws with the EU Parliament

Distribution: unweighted

Normal rule: qualified majority:

- 55% of members if proposed by Commission, or 72% otherwise

- 65% of EU population

- Note that proposals that fail to meet this can still go through unless at least four members vote against, to prevent the three largest members from having a veto

Special rules: unanimity but for fewer areas than previously (security and tax, but no longer for immigration, asylum, IP)

Notes

- “[T]o a significant degree, unanimity requirements in the Council are being replaced with a co-decision procedure that requires non-unanimous approval in both the Council and the Parliament. The movement away from unanimity has its roots in a desire to promote greater policy flexibility. But the enhanced role of Parliament limits the importance of that change.”[109]

Appendices

Voting share in major banks

From https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/GovernanceWorldBank.pdf:

Voting and design objectives

From Blake and Payton (2015):

Size and issue of IGOs

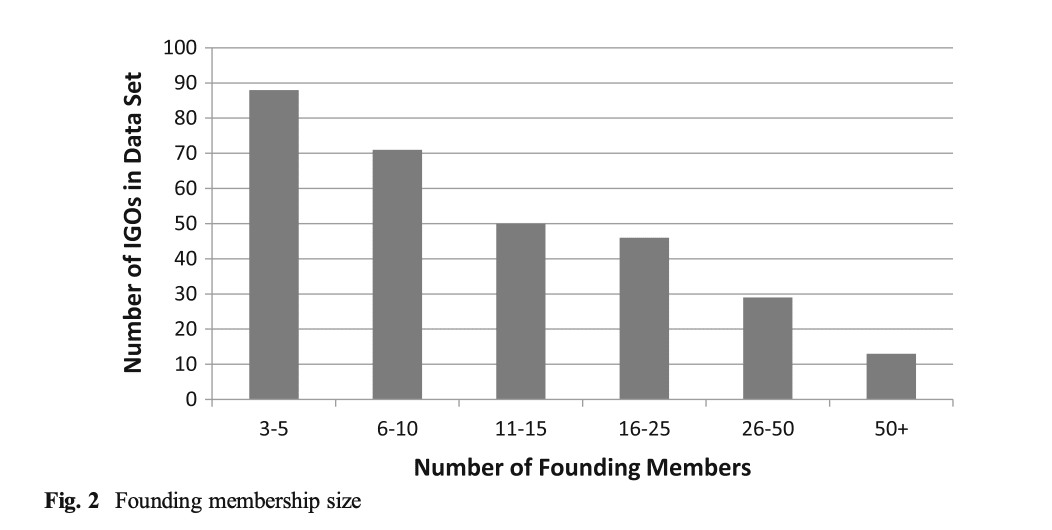

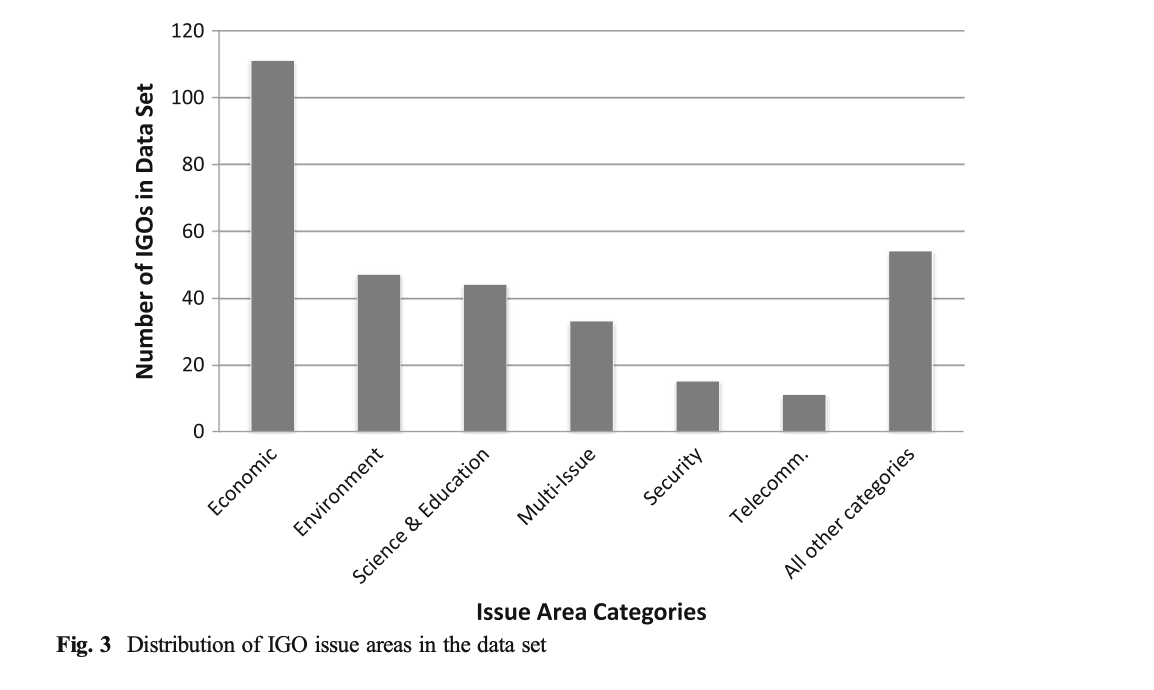

From Blake and Payton (2015), based on the Correlates of War IGO membership dataset between 1944 and 2005:[110]

IO effectiveness and legitimacy

From Panke, Polat and Hohlstein (2022). A survey of ~1000 delegates from ~50 IOs, responding to a Likert scale for their own organisation.

Selected bibliography

I haven’t included all of the sources I used on individual organisations, but these are included in footnotes.

The structure of institutions

Blake, D. J., & Payton, A. L. (2015). Balancing design objectives: Analyzing new data on voting rules in intergovernmental organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 10(3), 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-014-9201-9

Koremenos, B., Lipson, C., & Snidal, D. (2001). The Rational Design of International Institutions. International Organization, 55(4), 761–799. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081801317193592

Panke, D., Polat, G., & Hohlstein, F. (2022). Who performs better? A comparative analysis of problem-solving effectiveness and legitimacy attributions to international organizations. Cooperation and Conflict, 57(4), 433–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367211036916

Posner, E. A., & Sykes, A. (2014). Voting Rules in International Organizations (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2383469). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2383469

Zamora, S. (1980). Voting in International Economic Organizations. The American Journal of International Law, 74(3), 566–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2201650

Institutions relevant to AI

Karnofsky, H. (2023). Case studies on safety standards. Public Google Sheet. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/18gaTIzdgMvKLq9Cp2-GJZZA7QmE93Frufh1UhNMcbpg/edit?gid=1459002828#gid=1459002828

Hausenloy, J., & Dennis, C. (2023). Towards a UN Role in Governing Foundation Artificial Intelligence Models. https://unu.edu/cpr/working-paper/towards-un-role-governing-foundation-artificial-intelligence-models

Ho, L., Barnhart, J., Trager, R., Bengio, Y., Brundage, M., Carnegie, A., Chowdhury, R., Dafoe, A., Hadfield, G., Levi, M., & Snidal, D. (2023). International Institutions for Advanced AI (arXiv:2307.04699). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2307.04699

Maas, M. M., & Villalobos, J. J. (2023). International AI Institutions: A Literature Review of Models, Examples, and Proposals (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4579773). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4579773

Wasil, A., Barnett, P., Gerovitch, M., Hauksson, R., Reed, T., & Miller, J. (2024). Governing dual-use technologies: Case studies of international security agreements & lessons for AI governance. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2409.02779

Thanks to Will for suggesting the topic and giving guidance.

This article was created by Forethought. Read the original on our website.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 22.

- ^

“Under traditional international law, as exemplified by early diplomatic conferences, two basic truths controlled the question of voting: every state had an equal voice in international proceedings (the doctrine of sovereign equality of states), and no state could be bound without its consent (the rule of unanimity). These rules were bound together, and were extensions of the general principle of the state’s sovereign immunity from externally imposed legislation.” Zamora (1980), p. 571.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 4.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 590-599.

- ^

Common issues for special majorities include membership, finance, constitutional amendments, elections, and substantive decisions. Zamora (1980), p. 596.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 571-574.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 575.

- ^

“The turning point was World War I, which convinced statesmen that countries needed to cooperate more closely on security issues, and which gave rise to the League of Nations. Various more specialized organizations were founded in its wake”. Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 3.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 575-576.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 3.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 590.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 595.

- ^

“The data set contains cross-sectional information on the original voting rules, issue area, and founding membership for IGOs created between 1944 and 2005. The observations in the data set were drawn from the Correlates of War (COW) IGO membership data set (Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke v.2.3). To qualify as an IGO in the COW data set an organization must have a minimum of three members, possess a permanent secretariat and hold regular plenary sessions at least once every 10 years.” Blake and Payton (2015), p. 9.

- ^

“The coding rule we adopt to address the issue of multiple decision-making bodies within IGOs is to focus on a single body: the institutional organ that commands greatest authority over the IGO and the main substantive issues before the organization.”

“With respect to instances where decision rules within the supreme decision-making body vary by subject or issue, we code the voting rule that is applied for standard policy decisions and regular substantive issues that appear before the body.” Blake and Payton (2015), p. 12.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 599-601.

- ^

“The data set contains cross-sectional information on the original voting rules, issue area, and founding membership for IGOs created between 1944 and 2005. The observations in the data set were drawn from the Correlates of War (COW) IGO membership data set (Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke v.2.3). To qualify as an IGO in the COW data set an organization must have a minimum of three members, possess a permanent secretariat and hold regular plenary sessions at least once every 10 years.” Blake and Payton (2015), p. 9.

- ^

Equal votes between exporting and importing countries; weighted voting within the groups. These organisations have similar voting structures as they are mostly modelled on the International Wheat Agreement. “Under all the agreements, this weighting of votes gives a few large producers or consumers substantial veto power over decisions.” Zamora (1980), pp. 575-576.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 599-601.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 573, 590.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 1. “[W]hile courts can issue legally binding orders, states can almost always escape their jurisdiction by refusing to consent to it. And the powers of international courts tend to be highly limited…One possible reason for the ubiquity of majority rule for courts is that (outsider international criminal law and the WTO) judicial or arbitral proceedings usually commence only with the consent of both states, and supermajority rule, weighted voting, or any other system aside from majority rule would give the advantage to one state, eliminating the incentive of the other state to consent to legal process.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 21.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 21.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 6.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 6.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 589-590.

- ^

“These organizations are concerned with two sometimes opposing pressures: ensuring the support needed to implement decisions, and making decisions quickly and efficiently. The first pressure calls for formal voting procedures with built-in safeguards, such as special majorities and weighted voting, to ensure the support of the most influential members…. Paradoxically, the second pressure (efficiency) may compel disregard of the formal voting procedures… Various methods of majority voting may apply to these agencies, but in the interest of efficiency, the de facto decision making responsibility is informally delegated to a small group of actors comprised of high-level bureaucrats and officials of the most influential members.” Zamora (1980), pp. 589-590.

- ^

“This bypassing of formal procedures in the interests of efficiency is only possible if there is a high degree of goal consensus among members, since in most organizations a single dissenting member can force the organization to make a decision by formal vote.” Zamora (1980), pp. 589-590.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 595.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 596.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 591-592.

- ^

“The advantage of the unanimity rule is that the outcome must therefore make all states better off than the status quo—the outcome is Paretosuperior.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 4. See also Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1, below.

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1.

- ^

“This results from two distinct problems. First, there will often be a range of decisions that increase the aggregate welfare of the states (i.e., that are Kaldor-Hicks efficient – they provide gains to the winners that exceed the losses to the losers) but that do not satisfy the Pareto criterion. They may not receive unanimous support ex post unless transfers are arranged, and it may be expensive for states to arrange transfers to each other… Second, states can hold out under a unanimity rule whether or not they gain from a prospective decision, demanding a payoff in return for their consent.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 4. Zamora (1980) notes that unanimity means either things are blocked or they are watered down, neither of which allows effective functioning (p. 574). See also Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1, below.

- ^

“The states that lose from a Kaldor-Hicks efficient outcome are simply outvoted; transfers do not need to be arranged. Any state that threatens to hold out can also be outvoted.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 4. See also Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1, below.

- ^

“But now the problem is that the majority of states can force through a decision that is KaldorHicks inefficient and that transfers value from the minority to the majority. This risk of “exploitation” can make majority rule unattractive from an ex ante perspective: while decision costs are low, the voting rule permits inefficient outcomes as well as efficient outcomes, and so may in aggregate have negative net expected value.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 4. See also Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1, below.

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1.

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1.

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015), Table 1.

- ^

Panke, Polat and Hohlstein (2022). A survey of ~1000 delegates from ~50 IOs, responding to a Likert scale for their own organisation.

- ^

Equal votes between exporting and importing countries; weighted voting within the groups. These organisations have similar voting structures as they are mostly modelled on the International Wheat Agreement. “Under all the agreements, this weighting of votes gives a few large producers or consumers substantial veto power over decisions.” Zamora (1980), pp. 575-576.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 599-601.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 573, 590.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 573, 590.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 1. “[W]hile courts can issue legally binding orders, states can almost always escape their jurisdiction by refusing to consent to it. And the powers of international courts tend to be highly limited…One possible reason for the ubiquity of majority rule for courts is that (outsider international criminal law and the WTO) judicial or arbitral proceedings usually commence only with the consent of both states, and supermajority rule, weighted voting, or any other system aside from majority rule would give the advantage to one state, eliminating the incentive of the other state to consent to legal process.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 21.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 21.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 6.

- ^

“[T]he more important the purpose of the organization, the higher the normal majority requirement, with political and economic organizations generally having the highest normal majority requirements.” Zamora (1980), p. 595.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 596.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 1.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 6.

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015).

- ^

Blake and Payton (2015).

- ^

“Unlike the Bretton Woods Agreements, the Treaty of Rome does not indicate the criteria by which the weighted votes are assigned to members. Rather, different numbers of votes are simply assigned to different countries.” Originally:

- 10 for West Germany, France, Italy, UK

- 5 for Belgium, Netherlands, Greece

- 3 for Denmark, Ireland

- 2 for Luxembourg

- Total of 63 votes

All Council decisions are taken unanimously by common understanding. Zamora (1980), pp. 582-583.

- ^

Majority if proposed by the Commission, or ⅔ if not; AND 74% of weighted votes; AND 62% of the EU population. Unanimity for security and tax. Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 18-19.

- ^

Major powers have permanent seats. Small powers outnumber them, but this doesn’t matter as most issues require unanimity. Zamora (1980), pp. 572-573.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 12-15. https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/leadership/directors/eds09/voting-powers

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 597.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 598.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 15.

- ^

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 12-15.

- ^

“At present, for example, the largest member (the United States) holds approximately 17% of the votes. The smallest developing country member holds votes equal to a tiny fraction of 1%. In addition, members that are active borrowers from the IMF have their votes reduced.” Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 13.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 6-7.

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 579-580.

- ^

See also Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 9: “Any member could withdraw from GATT, and so a member believing itself to be exploited could just quit. Likewise, a member could simply deviate from its obligations and tell the rest of the members to go soak their heads. The remaining members might retaliate by deviating from their own obligations, in which case all pertinent parties would effectively opt out and return to their pre-GATT trade policies. But those policies were perceived to have been economically undesirable, and the negotiated commitments of GATT were a joint improvement. Thus, no party wanted to trigger a process by which GATT would unravel, and whatever potential may have existed in principle for opportunistic use of the voting rules was checked by the essentially self-enforcing nature of the bargain.”

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 574.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

Hausenloy and Dennis (2023).

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 574.

- ^

Maas and Villalobos (2023).

- ^

- ^

Slotten (2022), p. 173.

- ^

- ^

Slotten (2022), p. 173.

- ^

- ^

Zamora (1980), pp. 580-581.

- ^

Group of 77 (developing), group B (developed), group D (socialist). Votes only take place after blocs have an agreed common position. You can vote against your bloc, but it’s uncommon.

- ^

Zamora (1980), p. 601.

- ^

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 15-16.

- ^

“The Assembly currently has 166 members (including the European Union, which possesses one seat). The Council has 36 members, who are elected by the Assembly.” Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 15-16.

- ^

“[D]eep seabed mining, unlike other economic areas, is especially difficult for the developed countries to characterize as justifying a voting system weighted in their favor. It is a new activity, there are no major producers and consumers (in contrast to the commodity agreements), and any system of weighting, such as relative volume of trade, would not necessarily be acceptable or workable in this new economic sector.” Zamora (1980), p. 586.

- ^

“There is logic to this scheme: as the decision becomes more purely distributional, the risk of expropriation increases while the cost of inefficient gridlock—in the sense of lost opportunities to exploit resources—declines.” Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 15-16.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 16.

- ^

“The 1994 agreement gave the United States near-veto power by assuring it that it would belong to a chamber with three other similarly situated countries and the ability to block decisions as long as it could obtain the support of two of those other three. It is not clear why this system did not satisfy the United States but one reason may be that the U.S. government believes that agreement will be so hard to reach that it will become impossible to exploit the seabed resources, in which case overexploitation may be a less bad outcome than non-exploitation. On the other hand, a weaker voting system might force the United States to share revenues more than it is willing to do, given its presumed technological and economic advantages. It is puzzling that a deal cannot be reached given that all countries have an interest in the efficient exploitation of resources but an explanation may be that since it is not yet economically feasible to extract those resources, the U.S. government has a strong interest in holding out for a better deal.” Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 15-16.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 8-12.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 11.

- ^

- ^

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), pp. 18-19.

- ^

Posner and Sykes (2014), p. 19.

- ^

“The data set contains cross-sectional information on the original voting rules, issue area, and founding membership for IGOs created between 1944 and 2005. The observations in the data set were drawn from the Correlates of War (COW) IGO membership data set (Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke v.2.3). To qualify as an IGO in the COW data set an organization must have a minimum of three members, possess a permanent secretariat and hold regular plenary sessions at least once every 10 years.” Blake and Payton (2015), p. 9.