Escaping hedonic adaptation is hard

By Eva @ 2025-09-02T21:16 (+27)

We updated a paper with some new results on the effects of large sustained unconditional cash transfers in the US. For context, this was for an intervention in which low-income individuals in the treatment group received $1,000/month for 3 years, while a control group received $50/month over the same time period.

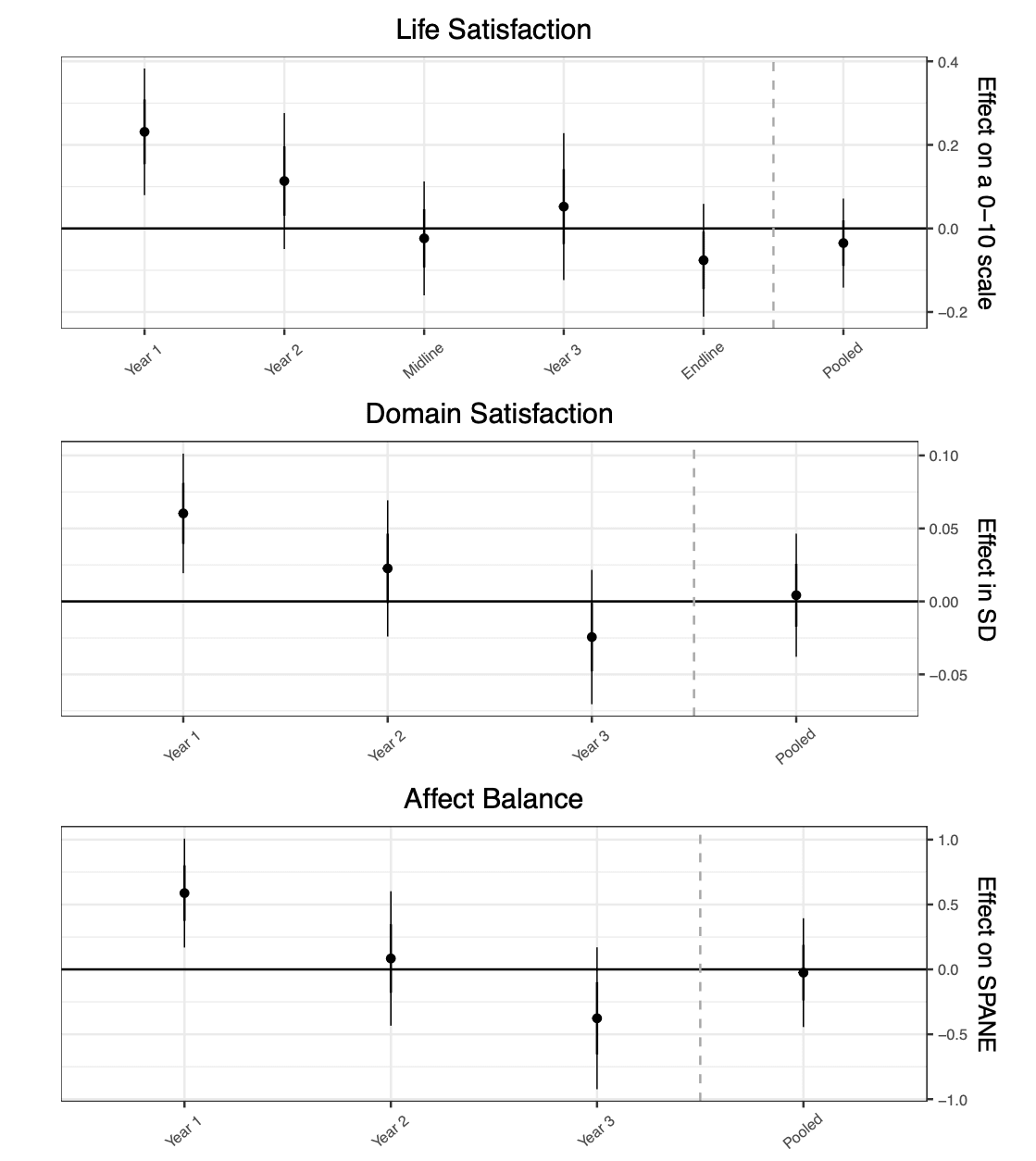

I've posted about it in more detail on social media (X / Bluesky), but I wanted to flag the new results on subjective well-being. Namely, these transfers - which represent 40% of baseline household income - have an effect on multiple different measures of well-being in year 1, but not in year 2 or 3.

We can't say for sure that it's hedonic adaptation. It could be plenty of other things.

I'll say that again: it could be plenty of other things.

But there's a large literature on hedonic adaptation, and it wouldn't be inconsistent with it. To the extent to which we care about improving well-being, I think people should grapple with adaptation more.

Eva @ 2025-09-03T18:22 (+4)

Some things it could be other than hedonic adaptation (non-exhaustive):

- People being disappointed that it's not making a bigger difference to their lives. Most experts thought there would be somewhat larger effects, so it's plausible participants did as well and are already starting to be disappointed by year 2.

- Expectations more generally not lining up to reality. For example, when someone leaves a job, we ask them how likely they think it is that they will find another acceptable job within 6 months. Almost everyone says they think they will find such a job, but then only about a third of people do in that timeframe. (Having a harder time finding a good job than anticipated is exceptionally common in all walks of life.)

- If you have money to do more things and then start to do more things, some of those things are not going to work out for you and you may have unexpected expenses. For example, you buy a car, and someone breaks into it. You move housing units, and it costs more than you expected to move or the gas bill is too high.

- There is a lot of churn in who is low-income, and while the transfers represent 40% of baseline household income, income rises in both the treatment and control group over the course of the study. So the transfers represent a relatively smaller boost in years 2 and 3. (Still, you might think that a 40% boost from baseline would affect well-being for longer.)

- Dynamic effects on other outcomes. For example, over time, fewer people work. In general, leisure is a normal good, and I think that is also the case here, by revealed preference. However, people could choose the wrong amount of it for themselves (e.g., through over-optimism in job search) and not working could lead to unexpected expenses biting harder.

- The earliest part of the study coincided with the brunt of the pandemic. Maybe it's easier to make people happier with cash during a pandemic (though note the effect could also go the opposite direction, given it was also easier to get other cash payments during this time).

One thing that is interesting is that well-being seems to be trending negative before the end of the study - not significantly, but still a bit concerning. If the study had only lasted one year, we might have incorrectly concluded the transfers made people durably better-off in terms of these subjective well-being measures. If the study lasted longer, though, would we see a continued decline, or are the negative point estimates just before the end a function of the transfers ending soon? (E.g., via regret or a negative anticipation effect?)

I still think hedonic adaptation is a very strong contender to explain the patterns we observe, because it shows up all over the place in the broader literature, to the point where if a study doesn't find an effect like that I wonder why. But, there are other things it could be. Either way, one might still be surprised the effects on subjective well-being aren't larger than they are, even in year 1. And, it's always possible to think the transfers made a meaningful difference to people's lives even if they did not show up in subjective well-being measures.

(Preference utilitarians might have a slightly easier time than hedonistic utilitarians here: while preference utilitarianism is more associated with life satisfaction or domain satisfaction and hedonistic utilitarianism more associated with affect balance, and we don't see lasting positive impacts on any of those measures, the transfers do enable more choice and people prefer more cash to less. We didn't see anyone turn down the transfers.)