Distinguish between inference scaling and "larger tasks use more compute"

By Ryan Greenblatt @ 2026-02-11T18:37 (+29)

As many have observed, since reasoning models first came out, the amount of compute LLMs use to complete tasks has increased greatly. This trend is often called inference scaling and there is an open question of how much of recent AI progress is driven by inference scaling versus by other capability improvements. Whether inference compute is driving most recent AI progress matters because you can only scale up inference so far before costs are too high for AI to be useful (while training compute can be amortized over usage).

However, it's important to distinguish between two reasons inference cost is going up:

- LLMs are completing larger tasks that would have taken a human longer (and thus would have cost more to get a human to complete)

- LLMs are using more compute as a fraction of the human cost for a given task

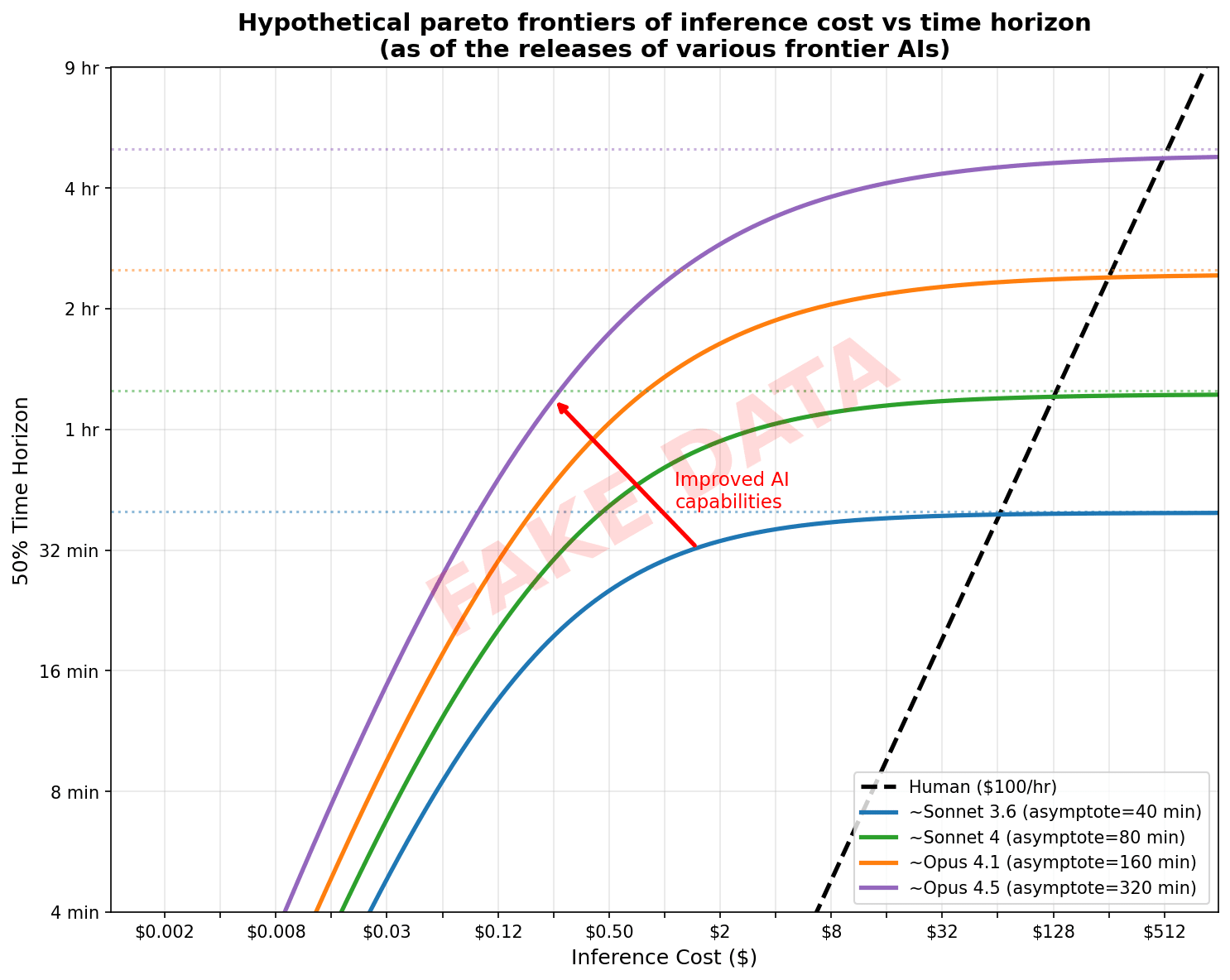

To understand this, it's helpful to think about the Pareto frontier of budget versus time-horizon. I'll denominate this in 50% reliability time-horizon.[1] Here is some fake data to illustrate what I expect this roughly looks like for recent progress:[2]

For the notion of time horizon I'm using (see earlier footnote), the (unassisted) human frontier is (definitionally) a straight line going all the way up to very long tasks.[3] (Further, there is a 1:1 slope in a log-log plot: a 2x increase in cost lets you complete 2x longer task. In the non-log-log version, the slope is the human hourly rate.) I expect LLMs start off at low time horizons with the same linear scaling and probably with roughly the same slope (where 2x-ing the time-horizon requires roughly 2x the cost) but then for a given level of capability performance levels off and increasing amounts of additional inference compute are needed to improve performance.[4] More capable AIs move the Pareto frontier a bit to the left (higher efficiency) and extend the linear regime further such that you can reach higher time horizons before returns level off.

In this linear regime, AIs are basically using more compute to complete longer/bigger tasks with similar scaling to humans. Thus, the cost as a fraction of human cost is remaining constant. I think this isn't best understood as "inference scaling", rather it just corresponds to bigger tasks taking more work/tokens![5] Ultimately, what we cared about when tracking whether performance is coming from inference scaling is whether the performance gain is due to a one-time gain of going close to (or even above) human cost or whether the gain could be repeated without big increases in cost.

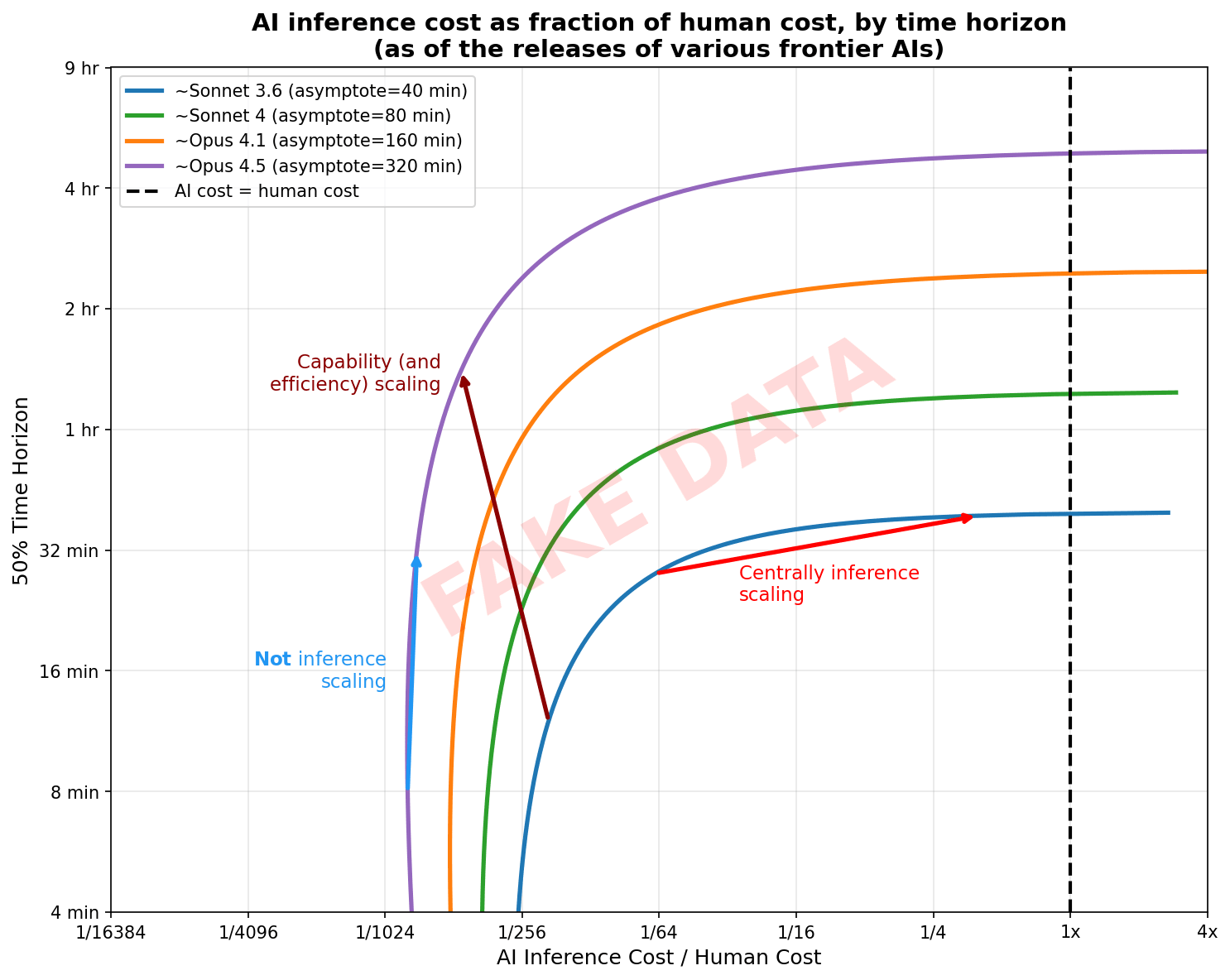

We can see this clearly by showing cost as a fraction of human cost (using my fake data from earlier):[6]

When looking at Pareto frontiers using fraction of human cost as the x-axis, I think it's natural to not think of mostly vertical translations as being inference scaling: instead we should think of this as just completing larger tasks with the same level of effort/efficiency. Inference scaling is when the performance gain is coming from increasing cost as a fraction of human cost. (Obviously human completion cost isn't deeply fundamental, but it corresponds to economic usefulness and presumably closely correlates in most domains with a natural notion of task size that applies to AIs as well.) Then, if a new model release shifts up the performance at the same (low) fraction of human cost (corresponding to the vertical scaling regime of the prior Pareto frontier), that gain isn't coming from inference scaling: further scaling like this wouldn't be bringing us closer to AI labor being less cost-effective than human labor (contra Toby Ord).

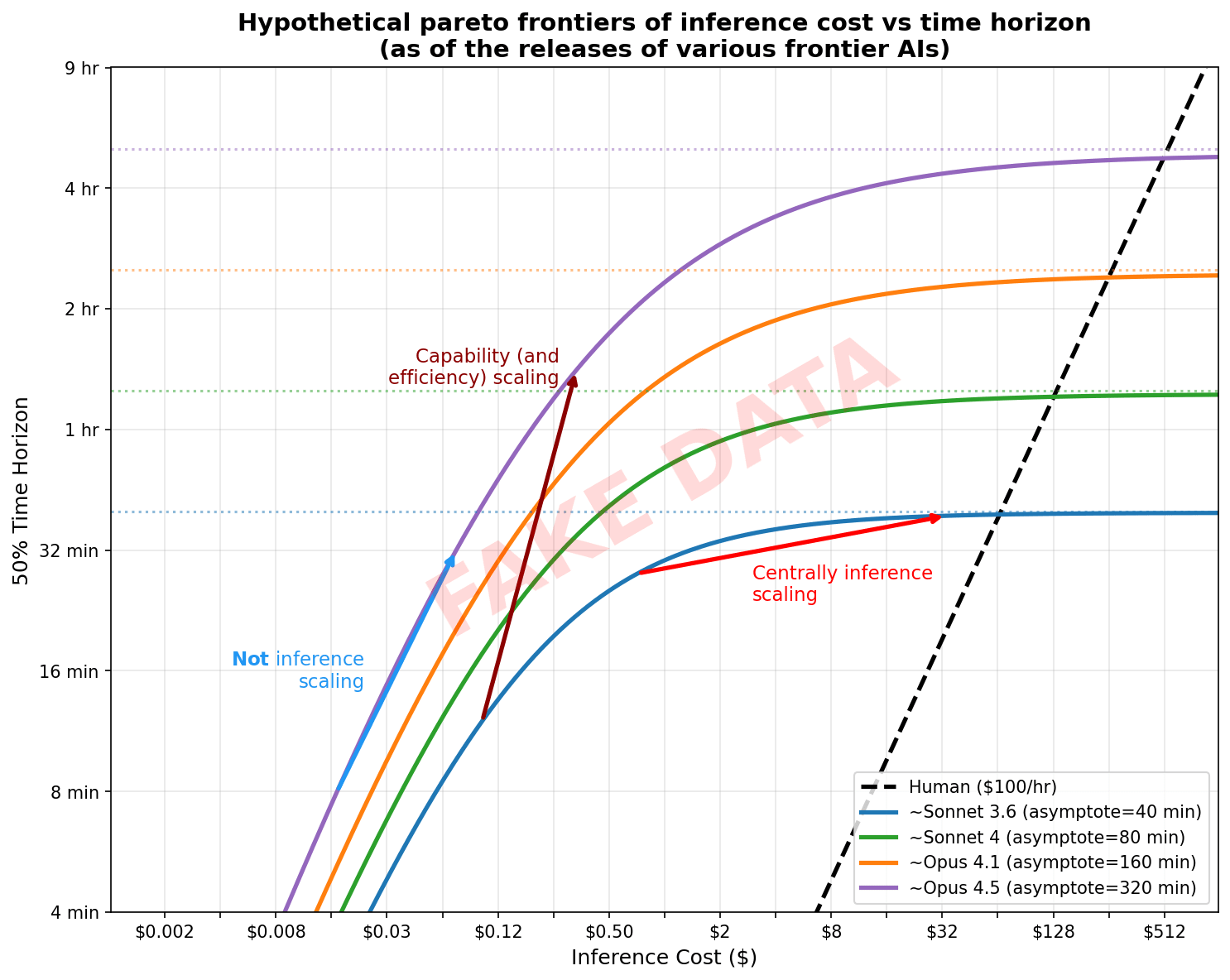

For reference, here are these same arrows on the original plot:

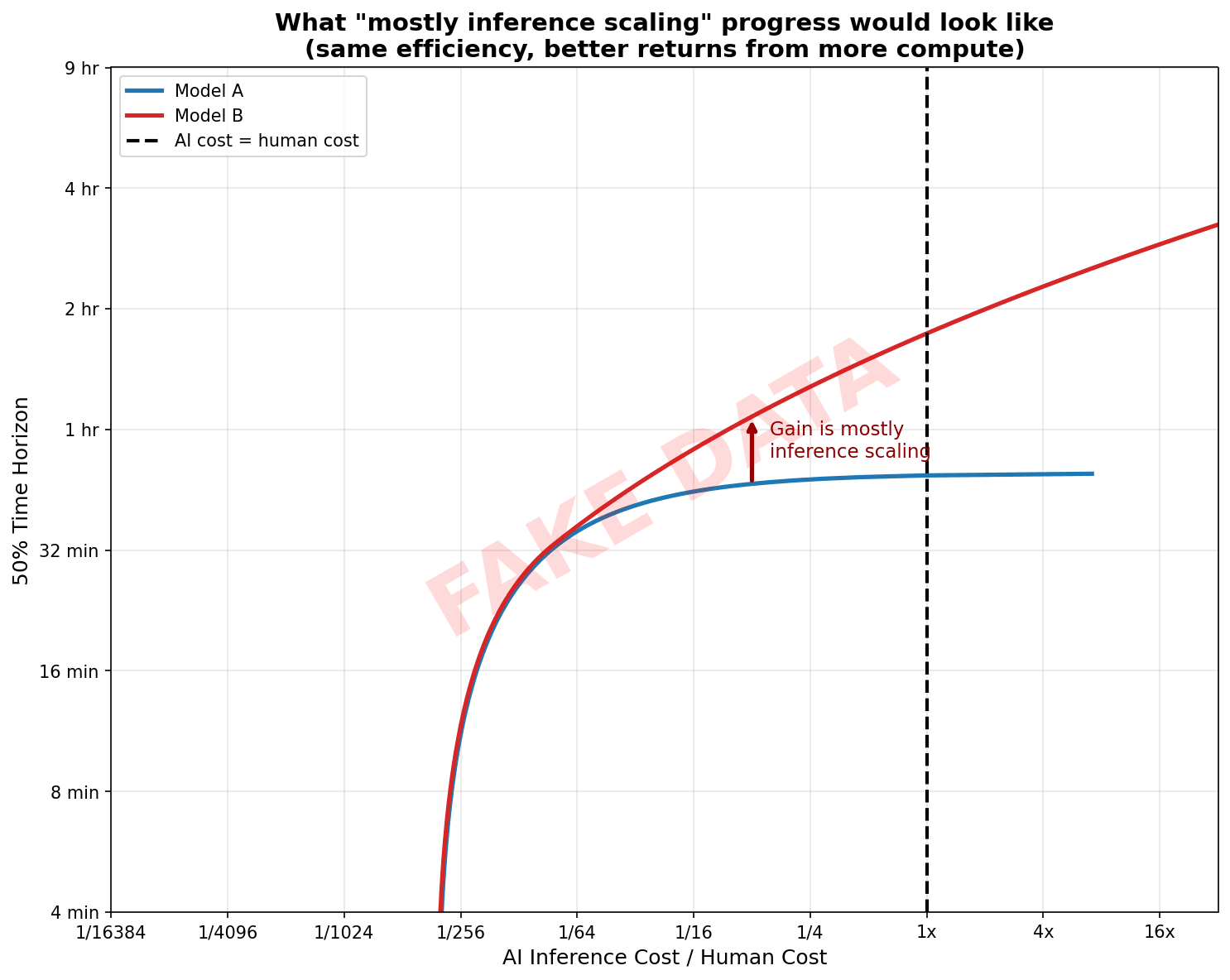

What would count as a new model release mostly helping via unlocking better inference scaling? It might look something like this:

I currently suspect that over 2025, the Pareto frontier mostly shifted like was illustrated in the prior plots rather than like this (though some shifts like this occurred, e.g., likely some of the key advances for getting IMO gold were about productively using much more inference compute relative to human cost).

To make some aspects of this graph cleaner, I'll say the time horizon of a given task is the amount of time such that if we randomly sample a human from our reference group of humans they have a 50% chance of completing the task. ↩︎

I'm assuming a maximum budget or an average cost for tasks with that exact time horizon rather than an average cost over the task suite (as this would depend on the number of tasks with shorter versus longer time horizons). ↩︎

This is simplifying a bit, e.g. assuming only a single human can be used, but you get the idea. ↩︎

Depending on the task distribution, this may asymptote at a particular time horizon or continue increasing just with much worse returns to further compute (e.g. for Lean proofs or easy-to-check software optimization tasks, you can keep adding more compute, but the returns might get very poor with an exponential disadvantage relative to humans). In some domains (particularly easy-to-check domains), I expect there is a large regime where the returns are substantially worse than 1-to-1 but still significant (e.g., every 8x increase in inference compute yields a 2x time horizon increase). ↩︎

In some cases, it might be effectively impossible to greatly reduce the number of tokens (e.g. for a software project, you can't do better than outputting a concise version of the code in one shot) while in others you could in principle get down to a single token (e.g., solving a math problem with a numerical answer), but regardless, we'd still expect a roughly linear relationship between time horizon and inference compute. ↩︎

I've supposed that AIs sometimes have a slight polynomial advantage/disadvantage such that the slope on the log-log plot isn't exactly 1 as this is what you'd realistically expect. ↩︎

Toby_Ord @ 2026-02-11T22:20 (+14)

Interesting ideas! A few quick responses:

- The data for the early 'linear' regime for these models actually appears to be even better than you suggest here. They have a roughly straight line (on a log-log plot), but at a slope that is better than 1. Eyeballing it, I think some are slope 5 or higher (i.e. increasing returns, with time horizon growing as the 5th power of compute). See my 3rd chart here. If anything, this would strengthen your case for talking about that regime separately from the poorly scaling high compute regime later on.

- I'd also suspected that when you apply extra RL to a model (e.g. o3 compared to o1) that it would have a curve that dominated the earlier model. But that doesn't seem to be the case. See the curves in the final chart here, where o1-preview is dominated, but the other OpenAI models curves all cross each other (being cheaper for the same horizon at some horizons and more expensive at others).

- Even when they do dominate each other neatly like in your fake data, I noticed that the 'sweet spots' and the 'saturation points' can still be getting more expensive, both in terms of $ and in terms of $/hr. I'm not sure what to make of that though!

- I think you're on to something with the idea that there is a problematic kind of inference scaling and a fine kind, though I'm not sure if you've quite put your finger on how to distinguish them. I suppose we can definitely talk about the super-linear scaling regime and the sub-linear regime (which meet at what I call the sweet spot), but I'm not sure these are the two types you refer to in qualitative terms near the top.

Ryan Greenblatt @ 2026-02-11T23:28 (+7)

Note that these METR cost vs time horizon are not at all pareto frontiers. These just correspond to what you get if you cut off the agent early, so they are probably very underelicited for "optimal performance for some cost" (e.g. note that if an agent doesn't complete some part of the task until it is nearly out of budget it would do much worse on this metric at low cost, see e.g. gpt-5 for which this is true). My guess is that with better elicitation you get closer to the regime I expect.

At some point, METR might run results where they try to elicit performance at lower budgets such that we can actually get a pareto frontier.

I agree my abstraction might not be the right ones and maybe there is a cleaner way to think about this.

Toby_Ord @ 2026-02-12T08:09 (+4)

Good point about the METR curves not being Pareto frontiers.