The catastrophic primacy of reactivity over proactivity in governmental risk assessment: brief UK case study

By JuanGarcia @ 2021-09-27T15:53 (+56)

Spanish version crossposted to riesgoscatastrogicosglobales.com

Summary

- I present two notable examples (the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption and the COVID-19 outbreak) of the following trend:

- Experts highlight the importance of a high uncertainty but high impact risk (to which the population is vulnerable and exposed).

- Some attention may be given by the government. Simulation exercises and/or reports may be carried out.

- Some preparedness work may get done based on these.

- The catastrophe takes place, catching institutions unprepared.

- The risk is then prepared for more seriously (at least for some time).

- I call this the “reactivity over proactivity” mindset.

- There are reasons to believe that this myopic mindset would have catastrophic consequences for humanity and its future.

- I give two notable examples of other risks that could follow the same path outlined above, with catastrophic consequences (extreme space weather and an extreme global food catastrophe).

- I make the case that at this moment there is low-hanging fruit to be picked in terms of interventions to address these risks, requiring little funding from governments (as a start to address this problem). One example is the development of fast response plans for rapid deployment of relevant technologies.

Context: Thanks to the podcast Planning for the Worst by BBC Radio 4 I realized there is plenty of data on how the UK government deals with risk assessment and response, so I decided to run a brief case study on it[1].

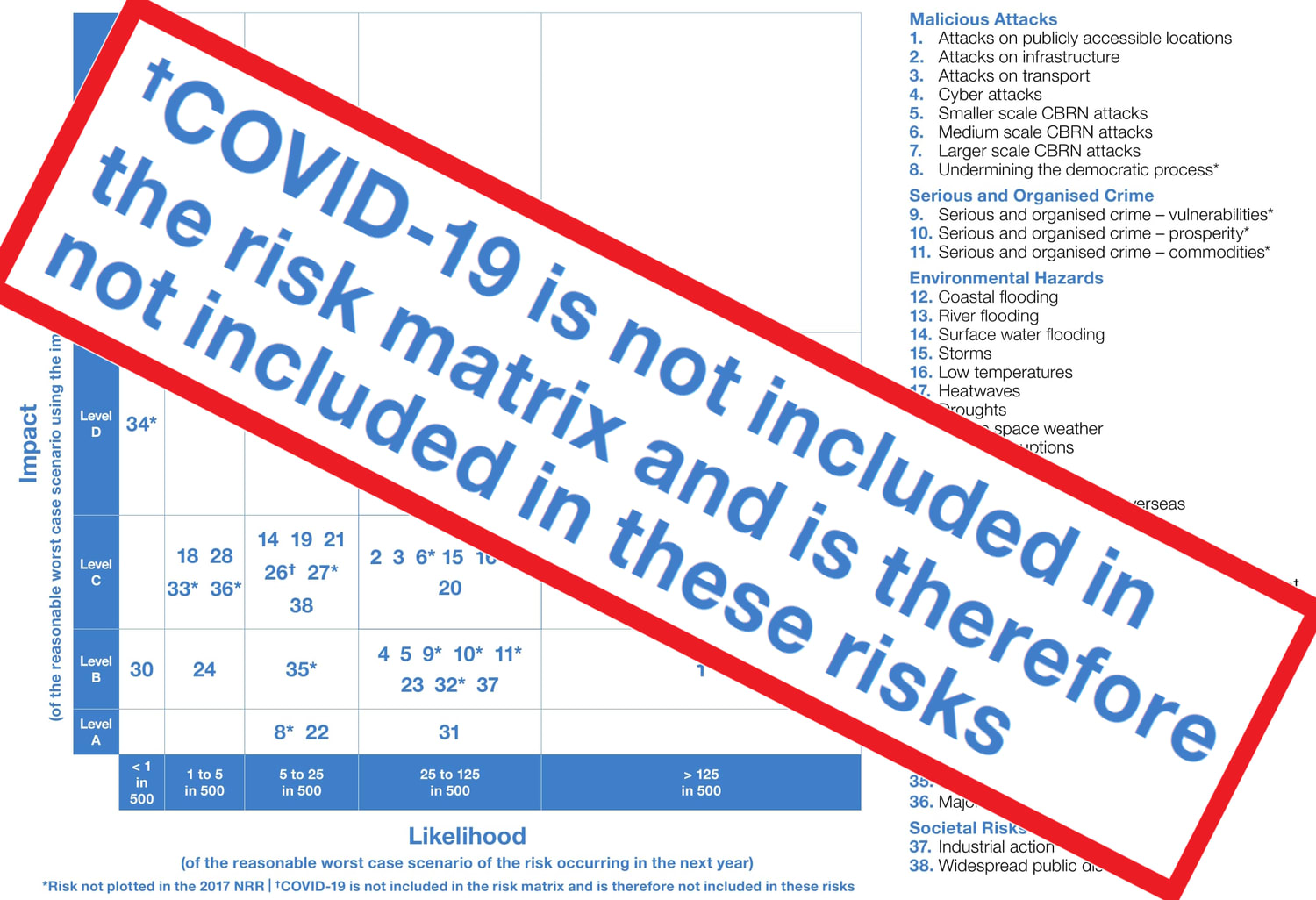

Note: The National Risk Register (NRR) of the UK is an official government report that serves as a summary of the assessment of important risks that may affect the country[2].

Two notable examples[3]

- The eruption of the icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 took UK institutions by surprise, but not researchers. Scientists had already raised the alarm, a government panel on the risk was carried out in 2005, and a report was created. No significant preparedness apparently developed from this though, and volcanic risk was only added to the NRR after the catastrophe in 2012.

- In 2016, the UK carried out exercise Cygnus, in which a secret simulation of a viral menace similar to COVID-19 was carried out to test UK preparedness. The report, which was later made public, clearly stated that the UK was unprepared for such a pandemic. The government has stated that they acted upon its recommendations and applied lessons learned.

- The risk of emerging infectious diseases was included in the NRR previous to COVID-19, with the potential severity estimated at “up to 100 fatalities”. The current edition of the NRR clarifies that COVID-19 is not included in the assessment.

- Based on the experience with Ebola, an early detection network for emerging viruses was set up, but at some point prior to the global pandemic it was no longer in operation, its work apparently diluted into “other forums and groups”.

Reasons for concern

Why is this important? Though not obvious at first glance, a mindset of taking a risk seriously only after calamity takes place could be catastrophic on many levels, including existential. In Bostrom's words:

“Our approach to existential risks cannot be one of trial-and-error. There is no opportunity to learn from errors. The reactive approach — see what happens, limit damages, and learn from experience — is unworkable. Rather, we must take a proactive approach. This requires foresight to anticipate new types of threats and a willingness to take decisive preventive action and to bear the costs (moral and economic) of such actions.”

— Nick Bostrom

Influencing governmental institutions and decision makers to be more proactive in their risk assessment appears to be of existential importance in the long term. Arguably, the UK is actually a leader and pioneer in the field of risk assessment, which does not speak positively as to how other countries may be dealing with high uncertainty, high impact risks that require foresight to prepare against. My experience with Spanish catastrophe preparedness officials has contributed to my belief that a lack of proactivity is widespread in risk assessment worldwide. Whether it is feasible for decision makers to seriously consider and act upon those risks that are not (or are no longer) in the public eye is anyone’s guess.

"The unfamiliar is not the same as the improbable"

— Lord Martin Rees

What are the next risks to which this pattern could apply?

I give two examples closely related to my own experience in global catastrophic risk research:

-

In 2015 the UK carried out a simulation of an extreme space weather event, which has been repeatedly highlighted by experts as a risk against which electrical infrastructure is “not even minimally resilient”. This event, or an EMP attack, could be capable of causing a collapse of the electrical and industrial infrastructure — disrupting communications, transportation, sanitation, food, and water supply — could last a year or longer, potentially returning the affected population to pre-industrial conditions for a long period of time. The UK report of the exercise can be found here, but it is yet to be seen whether the preparedness originating from it will yield a better result than that against volcanic and pandemic risk[4].

-

The risk of an extreme global food catastrophe has been highlighted by experts in scientific literature, there being multiple possible mechanisms for unleashing it, including supervolcanic eruptions. The NRR does not include this risk, probably because 1) it is considered as a consequence of other risks rather than a risk in its own right, or 2) the analysis does not sufficiently capture high-uncertainty, high-impact risks. Whatever the case, this likely leads to the UK being underprepared for food shortages, and potentially other similar risks.

So, what can be done? Some ideas:

-

Influencing governments to establish more general resilience and preparedness measures. For example, the countries that best dealt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were those more prepared for a flexible response against hypothetical new pathogens (Disease X), rather than focusing on previous known threats such as flu epidemics.

- In the words of Niall Ferguson: “Instead of trying to predict one or two future emergencies and prepare for them with cumbersome contingency plans, these countries emphasize rapid reaction and the deployment of technology to maximize their ability to turn on a dime.”

-

ALLFED is doing work on the topic of extreme food catastrophes, applying a similar rationale as above. Research on preparedness for rapid deployment of risk-resilient food production technologies to quickly ramp up food production appears to be a cost-effective way of preparing against this risk with limited funding, among other interventions. If funding were not so constrained, pilot tests for fast construction and deployment of resilient food production facilities could further increase preparedness (See here a summary of the idea as applied to industrial production facilities). Making food production systems inherently more resilient now would also help.[5]

-

CLTR has recently presented a list of cost-effective recommendations to the UK on the topic of preparing against high-uncertainty extreme risks with their Future Proof report. CSER has done much the same in their COVID-19 learnings report. Recommendations shared in these reports include normalizing red-teaming and creating a dedicated government body to prepare against the full range of threats. Much of these could be useful to other countries, so it would be valuable to translate/adapt these to different languages and regional contexts.

-

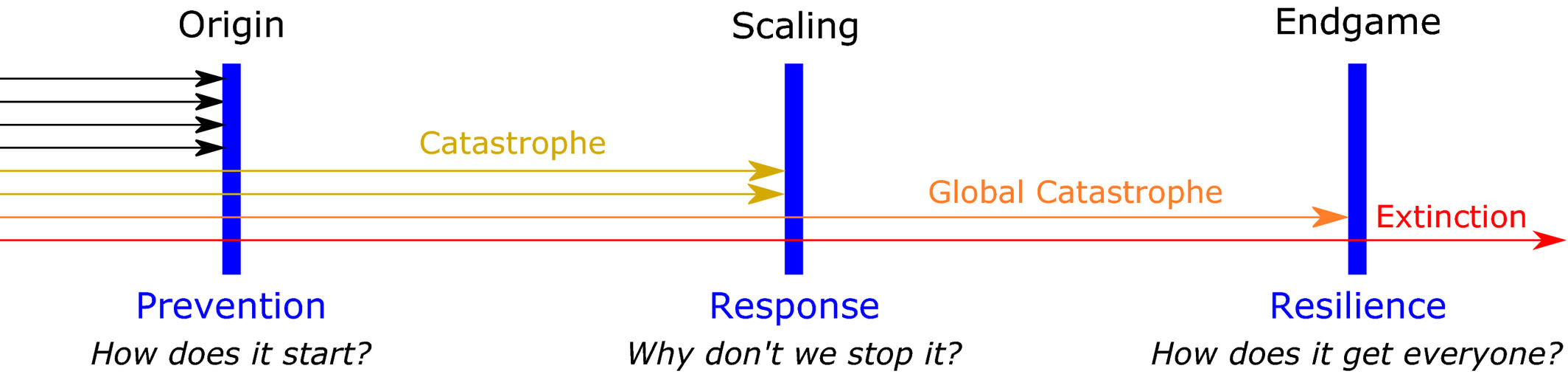

With respect to the connection between a reactive mindset and existential risk, increasing efforts to stimulate proactivity of decision makers in risk preparedness could be key for effectively responding to catastrophes and reacting on time before they escalate to the existential scale, as per the ”3 layers of defence against human extinction” model.

Three broad defence layers, from Defence in Depth Against Human Extinction: Prevention, Response, Resilience, and Why They All Matter by Owen Cotton-Barratt, Max Daniel, and Anders Sandberg.

Call for feedback

- How pervasive do you think this non-proactive mindset is in governments around the world?

- Are you aware of more notable examples for or against the non-proactive mindset in government?

- Are you aware of any interventions for increasing proactivity in risk preparedness?

- How could one identify and change the smallest possible part of a government necessary for risk prevention initiatives to be more proactive?

- Please let me know your thoughts on this, especially if you have experience with risk assessment or working with decision makers.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to David Denkenberger, Nuño Sempere, Jaime Sevilla, Ray Taylor, Morgan Rivers and Aron Mill for useful suggestions and comments.

Disclaimer: I use the UK as an example because it’s the country I’ve found the most data on, not because I specifically aim to critique the UK’s risk assessment capabilities. I have reasons to believe the problem outlined here is globally pervasive, and in the cases when it’s not the reason is often that the risks outlined by researchers do not even get any significant attention, which is worse. ↩︎

Most countries do not do this, which is bad. The fact that the NRR is open to the public makes it open to criticism, which is useful. I am aware Spain is working on something similar, which is a positive development that I’d like to see in more countries in the future. ↩︎

The 2008’s Great Recession could be another example. The UK was unprepared for it, although some experts had warned against it. However, the response was pretty good compared to many past recessions with a few exceptions globally. Preparedness against this type of risk seems to have improved compared to 2008, so I’d argue this counts as an example of reactivity over proactivity. ↩︎

Additional context by Morgan Rivers: UK has early warning systems in place for detecting solar storms before they arrive, and utility companies are aware of the issue and have engineers on standby to shut off the power to critical transformers in the grid to prevent excessive damage to them. The more expensive renovations, like putting GIC blocking in, still have not been done by the UK to my knowledge, although I believe it's been done in some Scandinavian countries. Other more expensive interventions have not been implemented by the UK. As a relatively small island longitudinally, the islands of the UK are inherently somewhat protected against the worst GICs as its overland power line system length is smaller in extent. On the other hand, it's at a somewhat high northern geomagnetic latitude increasing the risk. ↩︎

Disclaimer: I work as a research associate at ALLFED ↩︎