Making Resilience Visible for Sovereign Debt Pricing

By Sajriba @ 2025-10-04T20:32 (+2)

I’m Sajriba, a Leaf Fellow passionate about the intersection of climate resilience, economics, and global finance. One area interesting to me is how financial markets treat climate adaptation, especially the paradox that countries most vulnerable to climate shocks often pay the highest borrowing costs, even when they actively invest in resilience. This post introduces a framework I’ve developed called the Resilience Index Score (RIS) which attempts to quantify a country’s adaptive capacity and test whether resilience can (and should) be reflected in sovereign debt pricing. This is my first time posting on the EA Forum, and I’d be incredibly grateful for any thoughts, critiques, or suggested readings that could strengthen the work or help expand it into a broader collaborative effort!

In 2022, the IMF reported that 58% of low-income countries were already in or at high risk of debt distress. At the same time, the Global Center on Adaptation found that adaptation finance makes up only 7% of total climate finance globally, and just 3% reaches fragile economies.

Here’s the paradox: even when countries do invest in resilience such as strengthening flood defences, expanding renewable energy, or building foreign exchange reserves; global financial markets rarely reward them with cheaper borrowing.

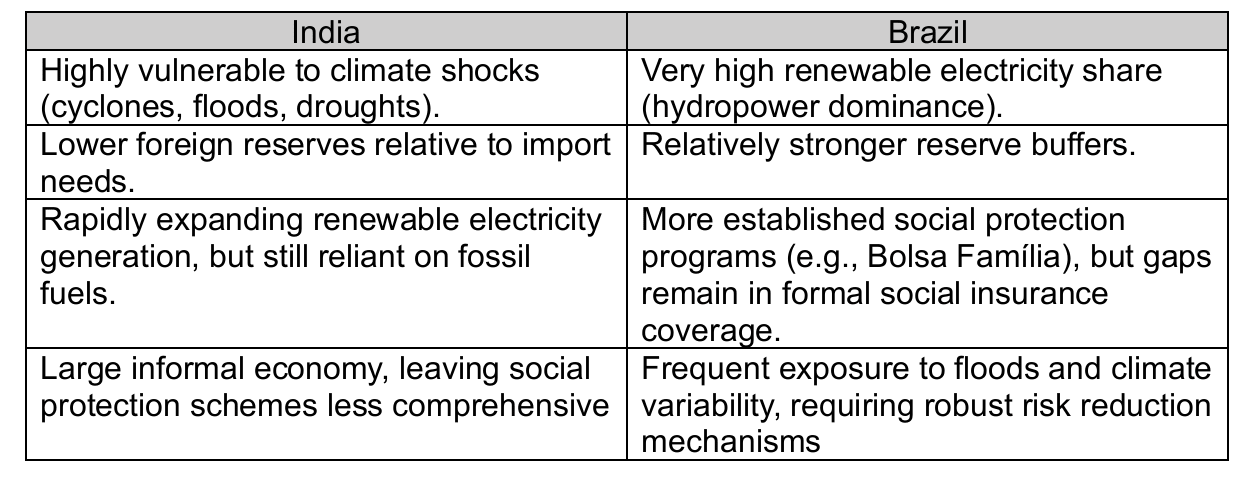

Taking two emerging economies from my pilot study: India and Brazil. India has steadily expanded its renewable energy output and built fiscal reserves over the last decade. Brazil, meanwhile, entered the 2010s with one of the world’s highest renewable electricity shares. Yet both countries still faced rising lending rates after climate-related shocks. In other words, markets priced the risks, but not the resilience.

This raises a critical question: Why should governments borrow at the same cost whether they invest in climate adaptation or not?

Introduction

Studies find that countries more exposed to physical climate shocks face higher sovereign spreads and ratings downgrades:

- The European Central Bank shows that climate vulnerability raises sovereign borrowing costs through fiscal volatility and weaker growth prospects.

- Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute documents how physical risks like heatwaves and floods are increasingly transmitted into sovereign risk pricing.

- Cambridge researchers argue that climate vulnerability already depresses sovereign credit ratings, creating a hidden “climate debt premium” for vulnerable nations.

What remains missing is the other side: adaptation and resilience capacity. A country may expand renewable electricity, build reserves, strengthen social protection, or invest in disaster preparedness but these efforts are not visible in credit assessments. As a result, governments are often penalised for climate risk exposure regardless of whether they are actively reducing it.

After a climate-related disaster, sovereign borrowing costs can spike by up to 200 basis points (IMF, 2022). For countries already spending up to one-fifth of revenue on debt servicing, this difference can mean billions lost to interest payments instead of being invested in schools, hospitals, or resilient infrastructure. By ignoring resilience, current market models not only misprice risk but also punish progress and lock vulnerable nations into cycles of debt and disaster.

Resilience Index Score (RIS)

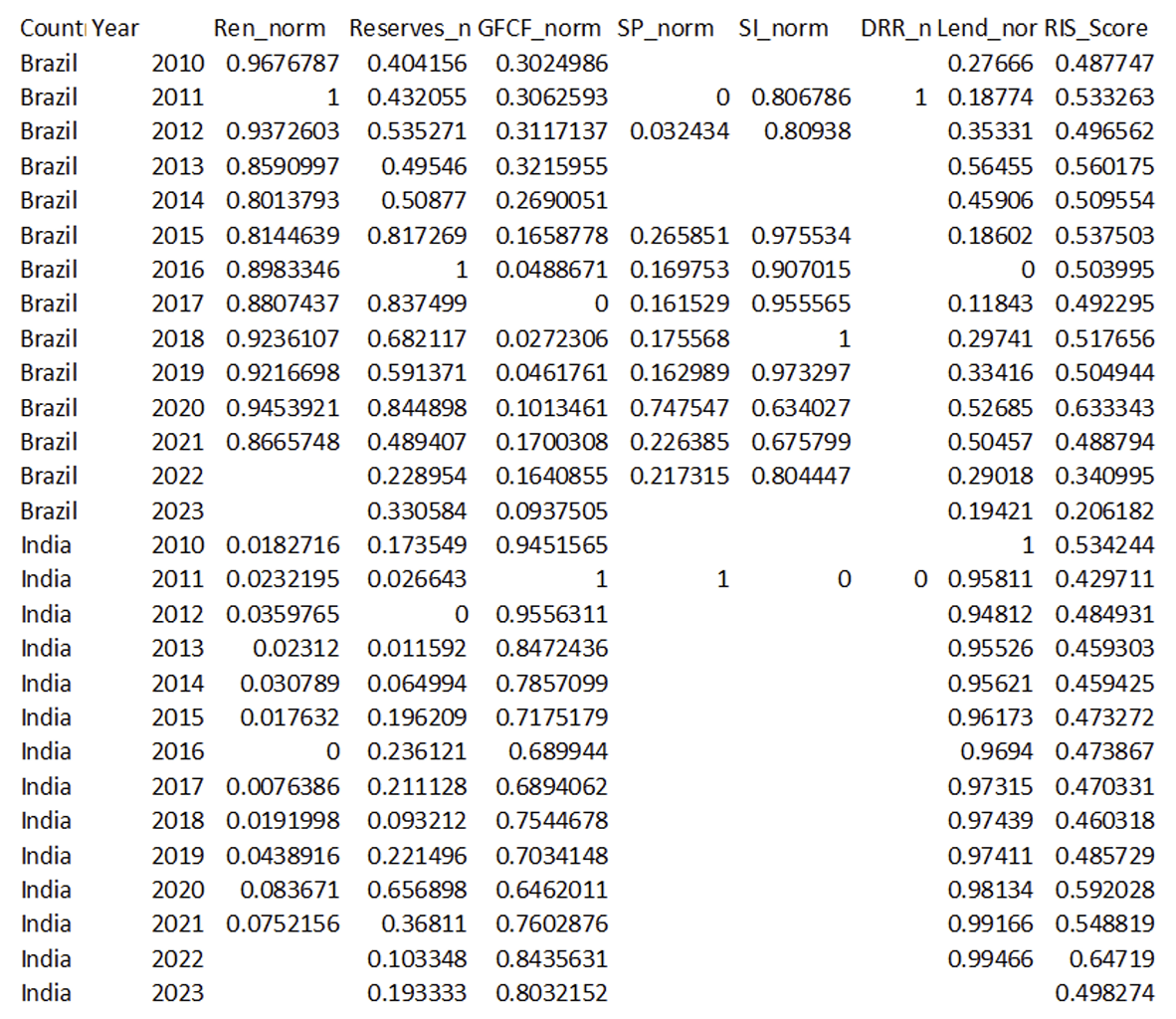

Resilience Index Score (RIS) is designed to quantify adaptation capacity across multiple dimensions and show how that capacity relates to sovereign financing conditions. The RIS aggregates six readily available indicators (renewable electricity share, reserves measured in months of imports, gross fixed capital formation, coverage of social protection programs, coverage of social insurance, and a disaster risk reduction progress score) after min–max normalization to a 0–1 scale, producing a single, interpretable resilience score for each country-year using lending interest rates as a practical, high-frequency proxy for sovereign borrowing cost in the pilot tests and using a panel drawn from carefully cleaned World Bank and institutional datasets for Brazil and India (2010–2023).

The results show that higher RIS is associated with lower lending rates in both case studies, with the strongest market sensitivity to financial buffers (reserves) and capital stock, suggesting markets implicitly reward certain forms of resilience while undervaluing social protections and preparedness.

Building the RIS

This study focuses on India and Brazil as two emerging economies with distinct resilience profiles but comparable exposure to climate risks.

To create a single resilience measure, each indicator is normalised between 0–1, ensuring comparability.

RIS=(Renewablenorm+Reservesnorm+GFCFnorm+SocialProtnorm+SocialInsnorm+ DRRnorm)/6

This produces a continuous RIS score between 0 (least resilient) and 1 (most resilient) for each country-year. The Lending Interest Rate remains in percentage terms, as the outcome variable of interest. This RIS framework allows direct comparison of resilience levels and trends between India and Brazil, and links them quantitatively to observed borrowing costs. Instead of focusing mainly on vulnerability, this method foregrounds resilience capacity as a potential explanatory variable.

Analysis and Results

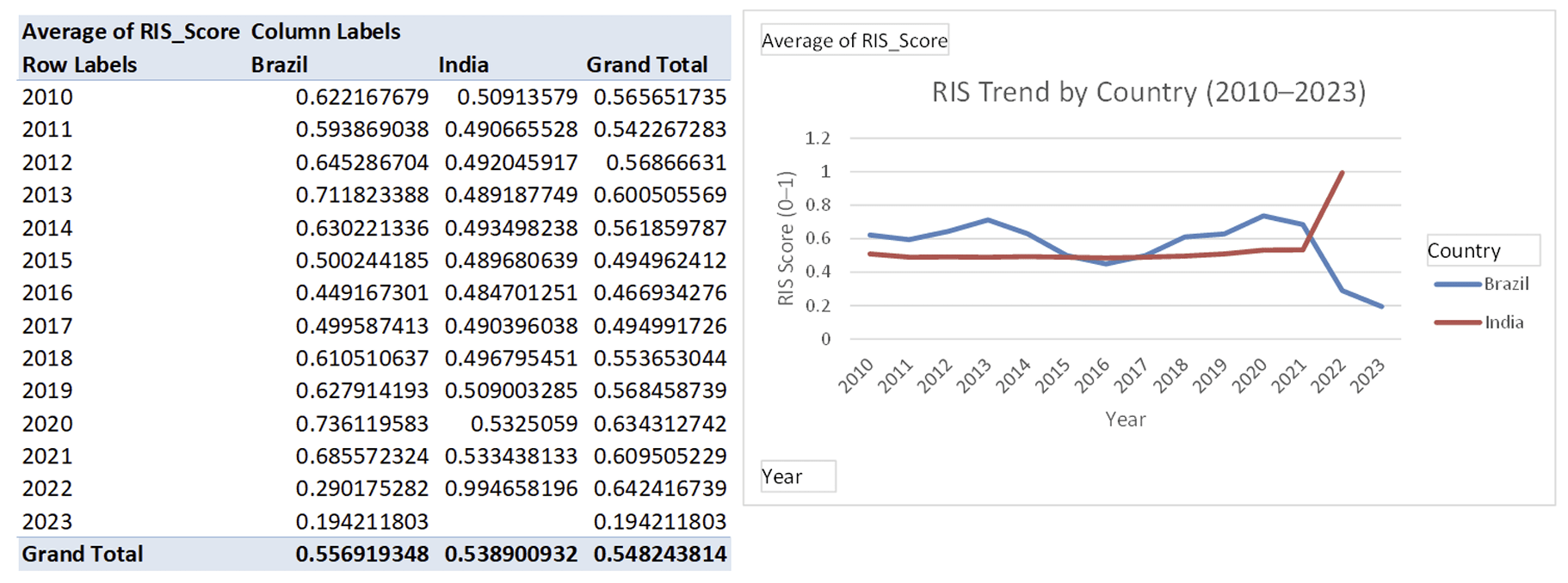

The empirical application of RIS to India and Brazil (2010–2023) provides stark insights:

- Brazil’s decline in resilience: despite Brazil’s initial advantages such as a high share of renewable energy and solid reserves, its resilience score plummeted in the post-pandemic years (down to 0.19 by 2023). This dramatic fall highlights the fragility of resilience investments that are not consolidated over time. The weakening of reserves, capital stock, and social protection systems contributed to a diminished ability to cope with shocks, revealing an urgent need for sustained investment in resilience across all sectors.

- India’s resilience ascendency: conversely, India, starting from a lower base, experienced a consistent upward trajectory in its RIS, rising from 0.50 in 2010 to 0.99 in 2022. This improvement, driven by strategic investments in capital formation and reserves, resulted in markedly lower borrowing costs. India’s experience shows how proactive resilience building, particularly in reserves and investment can provide a tangible economic advantage, even in a country with significant fiscal challenges.

- Market response: the data reveal a strong correlation between resilience and borrowing costs, with India’s relationship at −0.74, suggesting that investors increasingly price resilience into sovereign debt markets. This effect, however, is not universal. In Brazil, where resilience weakened post-2020, the correlation is weaker (−0.33), reflecting that markets may undervalue social resilience (e.g., social protection, DRR).

The RIS highlights adaptation as a central pillar of sovereign risk, urging policymakers and investors to rethink what constitutes true sovereign resilience. The traditional view of sovereign risk models focuses almost exclusively on fiscal health and growth prospects, overlooking the long-term importance of climate resilience. This oversight has real-world consequences:

- Financial markets are underpricing climate adaptation. By neglecting factors like social protection and disaster preparedness, they penalize countries investing in equitable resilience measures, which could entrench inequality.

- Resilience-building can lower borrowing costs. The study shows that nations investing in resilience (particularly through reserves, infrastructure, and renewable energy) see real financial returns in the form of lower sovereign borrowing costs. This creates a virtuous cycle: lower borrowing costs free up fiscal space, which can be reinvested in further adaptation.

- The research underscores the need for more inclusive financial models that recognize not only economic buffers but also the social and institutional dimensions of resilience. Countries investing in social protection and disaster risk reduction face systemic market invisibility, perpetuating inequities.

Broader implications

Beyond sovereign debt markets, the RIS framework offers a rigorous, data-driven method for rating agencies, multilateral development banks, and institutional investors to integrate adaptation into credit risk assessments. By making resilience quantifiable and investable, this framework could help shift trillions of dollars in global capital flows toward sustainable, human-centered climate solutions. Moreover, by explicitly valuing adaptation, RIS strengthens the climate finance agenda:

- Encouraging private sector innovation in green bonds, catastrophe bonds, and climate derivatives.

- Supporting the mainstreaming of adaptation within global finance.

- Accelerating progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly by reducing inequality, enhancing climate resilience, and promoting sustainable growth pathways.

Conclusion

The RIS framework challenges the very premise of how sovereign risk is priced in financial markets by bringing climate resilience into the fold. The study makes a critical contribution to understanding how climate adaptation is reshaping global finance and offers a pragmatic, quantifiable tool for policymakers, investors, and multilateral organizations to promote sustainable development and equity in sovereign risk assessments. The RIS framework represents a pivotal moment for financial inclusion in climate adaptation, which could reshape the global landscape for sovereign finance and the fight against climate change.