AI takeoff and nuclear war

By Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-06-11T19:33 (+72)

This is a linkpost to https://strangecities.substack.com/p/ai-takeoff-and-nuclear-war

Summary

As we approach and pass through an AI takeoff period, the risk of nuclear war (or other all-out global conflict) will increase.

An AI takeoff would involve the automation of scientific and technological research. This would lead to much faster technological progress, including military technologies. In such a rapidly changing world, some of the circumstances which underpin the current peaceful equilibrium will dissolve or change. There are then two risks[1]:

- Fundamental instability. New circumstances could give a situation where there is no peaceful equilibrium it is in everyone’s interests to maintain.

- e.g. —

- If nuclear calculus changes to make second strike capabilities infeasible

- If one party is racing ahead with technological progress and will soon trivially outmatch the rest of the world, without any way to credibly commit not to completely disempower them after it has done so

- e.g. —

- Failure to navigate. Despite the existence of new peaceful equilibria, decision-makers might fail to reach one.

- e.g. —

- If decision-makers misunderstand the strategic position, they may hold out for a more favourable outcome they (incorrectly) believe is fair

- If the only peaceful equilibria are convoluted and unprecedented, leaders may not be able to identify or build trust in them in a timely fashion

- Individual leaders might choose a path of war that would be good for them personally as they solidify power with AI; or nations might hold strongly to values like sovereignty that could make cooperation much harder

- e.g. —

Of these two risks, it is likely simpler to work to reduce the risk of failure to navigate. The three straightforward strategies here are research & dissemination, to ensure that the basic strategic situation is common knowledge among decision-makers, spreading positive-sum frames, and crafting and getting buy-in to meaningful commitments about sharing the power from AI, to reduce incentives for anyone to initiate war.

Additionally, powerful AI tools could change the landscape in ways that reduce either or both of these risks. A fourth strategy, therefore, is to differentially accelerate risk-reducing applications of AI. These could include:

- Tools to help decision-makers make sense of the changing world and make wise choices;

- Tools to facilitate otherwise impossible agreements via mutually trusted artificial judges;

- Tools for better democratic accountability.

Why do(n’t) people go to war?

To date, the world has been pretty good at avoiding thermonuclear war. The doctrine of mutually assured destruction means that it’s in nobody’s interest to start a war (although the short timescales involved mean that accidentally starting one is a concern).

The rapid development of powerful AI could disrupt the current equilibrium. From a very outside-view perspective, we might think that this is equally likely to result in, say, a 10x decrease in risk as a 10x increase. Even this would be alarming, since the annual probability seems fairly low right now, so a big decrease in risk is merely nice-to-have, but a big increase could be catastrophic.

To get more clarity than that, we’ll look at the theoretical reasons people might go to war, and then look at how an AI takeoff period might impact each of these.

Rational reasons to go to war

War is inefficient; for any war, there should be some possible world which doesn’t have that war in which everyone is better off. So why do we have war? Fearon’s classic paper on Rationalist Explanations for War explains that there are essentially three mechanisms that can lead to war between states that are all acting rationally:

- Commitment problems

- If you’re about to build a superweapon, I might want to attack now. We might both be better off if I didn’t attack, and I paid you to promise not to use the superweapon. But absent some strong commitment mechanism, why should I trust that you won’t break your promise and use the superweapon to take all my stuff?

- This is the main mechanism behind expecting war in the case of the Thucydides Trap

- Private information, plus incentives to misrepresent that information

- If each side believes themselves to have a military advantage, plus cannot trust the other side’s self-reports of their strength, they may go to war to resolve the issue

- Issue indivisibility

- If there is a single central issue at stake, and we can’t make side-payments or agree to abide by a throw of the dice, we may have no other choice than to determine it via war

- I side with Fearon in having the view that this is a less important mechanism, although for completeness I will discuss it briefly below

Irrational reasons to go to war

Alternatively, as Fearon briefly explains, there are reasons states may go to war even though it is not in their rational interest to do so:

- 4. Irrational decision-making

- People can just make mistakes, especially when they’re stressed or biased. Some of those mistakes could start wars.

- 5. Decision-makers who are misaligned with the state they are deciding for

- If a leader stands to collect the benefits of a war but not pay its costs, they may choose it

Finally, I want to note that an important contributory factor may be:

- 6. National pride

- Decision-makers may let themselves be steered strongly by what is good for the autonomy and sovereignty of their nation, and be very reluctant to trade them even if it is necessary for reaching the required levels of global coordination

- This could occur out of a deep-seated belief that this is the noble cause; or fear of being seen as insufficiently patriotic; or both

- Decision-makers may let themselves be steered strongly by what is good for the autonomy and sovereignty of their nation, and be very reluctant to trade them even if it is necessary for reaching the required levels of global coordination

(My understanding is that Fearon takes a neo-realist stance which wouldn’t classify this as irrational, but from my perspective it’s an important source of misalignment between states as decision-makers and what would be good for the people who live in them, and so worth mentioning. It won’t by itself suffice to explain a war, but it could be a contributory factor.)

Impacts of AI takeoff on reasons to go to war

We’ll consider in turn the effects on each of the possible reasons for war. The rapidity of change during an AI takeoff looks to increase the risk both of people starting a nuclear war for rational reasons (i.e. fundamental instability), as well as people starting a nuclear war for irrational reasons (i.e. failure to navigate to a peaceful equilibrium).

(Note that this section is just an overview of the effects of things speeding up a lot; I’ll get to the effects of particular new AI applications later.)

Impacts on rational reasons for war

Commitment issues

At present a lot of our commitment mechanisms come down to being in a repeated game. If a party violates things that are expected of them, they can receive some appropriate sanctions. If a state began nuclear war, its rivals could retaliate.

A fast-changing technological landscape threatens to upend this. An actor who got far ahead, especially if they developed technologies their rivals were unaware of, could potentially take effective control of the whole world, preventing those affected from retaliating. But a lack of possible retaliation means that they might face no disincentive to do so. And so the actor who was behind, reasoning through possible outcomes, might think they had no better option than starting a war before things reached that stage.

Other concerns include the possibility that the military landscape might move to one which was offence-dominant. Then even an actor who was clearly in the lead might attack a rival to stop them developing any potentially-destructive technologies. Or if new technology threatened to permit a nuclear first-strike to eliminate adversaries’ second-strike capabilities, the clear incentive to initiate war after that technology was possible could translate into some actors having an incentive to initiate war even before the technology came online.

Private information

States may have private information about their own technological base, and about future technological pathways (which inform both their strategic picture, but also their research strategy). If underlying technologies are changing faster, the amount and value of private information will probably increase.

While not conclusive, an increase in private information seems concerning. It could precipitate war, e.g. from someone who believes they have a technological advantage, but cannot deploy this in small-scale ways without giving their adversaries an opportunity to learn and respond; or from a party worried that another state is on course to develop an insurmountable lead in research into military technologies (even if this worry is misplaced).

Issue indivisibility

Mostly I agree with Fearon that this is likely rarely a major driver of war. Most likely that remains true during an AI takeoff. However, novel issues might arise, on which (at least in principle) there might be issue indivisibility. e.g.

- If one side were vehemently against the introduction of powerful AI by any parties, and others actively sought to develop AI

- If one side were committed libertarian about what types of systems people could make, and another had red lines around freedom to create systems that could suffer

- Maybe AI could help make indivisible issues less frequent, via making it more possible to explore the full option space and find clever deals

- This is based on the idea that often “indivisible” issues are not truly indivisible, merely hard-to-divide

- Maybe AI could help make indivisible issues less frequent, via making it more possible to explore the full option space and find clever deals

Impacts on irrational reasons for war

Irrational decision-making

During an AI takeoff, the world may feel highly energetic and unstable, as technological capabilities are developed at a rapid pace. People may not grasp the strategic implications of the latest technologies, and are even less likely to fully understand the implications of expected future developments — even if those will come online within the next year.

If the situation becomes much harder to understand, and without a track record of similar situations to have learned from, it will become much easier to act less-than-fully-rationally. People might make big errors, even while acting in ways that we might think looked reasonable.

Of course, less-than-fully-rational doesn't imply that there will be war, but it weakens the arguments against. People might initiate war if they mistakenly believe themselves to be in one of the situations where there is rational justification for war. Or they might initiate war if they believe the other parties to be acting sufficiently irrationally in damaging ways that it becomes the best option to contain that.

Many people would have a moral aversion to the idea of starting a nuclear war. It is a hopeful thought that this would bias even irrational action against initiating war. However, this consideration feels a bit thin to count on.

(Also, all of these situations could be very stressful, and stress can inhibit good decision-making in a normal sense.)

Misaligned decision-makers

I'm not sure takeoff will have a big effect on the extent to which decision-makers are misaligned. But there are a couple of related considerations that give some cause for alarm:

- As AI becomes more powerful, dictators might reasonably start to hope to hold absolute power without support from other humans

- This could reduce one of the checks keeping their actions aligned (since nuclear war will typically be very unpopular)

- Faster takeoffs could reduce the capacity of normal mechanisms to provide democratic accountability

- i.e. even the leaders of democratic countries may come to believe that the ballot box will not be the primary determinant of their future

National pride

It is quite plausible that the unsettling nature of a takeoff period will make things feel unsafe to people in ways that push their mindset towards something like national pride — binding up their notion of what acting well and selflessly is with protecting the dignity and honour of their civilization or nation. This could occur at the level of the leadership, or the citizenry, or both.

Generally high levels of national pride seem to make the situation more fraught, because they narrow the space of globally-acceptable outcomes — it becomes necessary not only to find outcomes that are good for all of the people, but also for the identity of the nations (as projected by the people running them). This could, for example, be a blocker on reaching agreements which avert war by giving up certain sorts of sovereignty to an international body.

Strategies for reducing risk of war

Strategies for averting failure to navigate takeoff

Nuclear war seems pretty bad[2]. It may therefore be high leverage to pursue strategies to reduce the risk of war. The straightforward strategies are education, and getting buy-in to meaningful commitments.

Research & dissemination

A major driver of risk is the possibility that the rate of change will mean that decision-makers are out of their depth, and acting on partially-wrong models about the strategic situation.

An obvious response is to produce, and disseminate, high-quality analysis which will help people to better understand the strategic picture.

This seems likely a good idea. While there are some possible worlds where things reach better outcomes because some people don't understand the situation and are blindsided, a strategy of deliberately occluding information feels very non-robust.

Spreading “we’re all in this together” frames

The more people naturally think of this challenge as a contest between nations, the more likely they are to make decisions on the basis of national pride, and the harder it may be to get people to come together to face what may be the grandest challenge for humanity — preserving our dignity as we move into a world where human intelligence is not supreme.

On the other hand, I think that getting people unified around frames which naturally put us all in the same boat is likely to have some effect reducing the impact of national pride on decision-making, and hence reduce the risk of war. Of course this is dependent on how far a reach these frames could have — but I think that as the world becomes stranger people will naturally be reaching for new frames, so there may be some opportunity for good frames to have a very wide reach.

Agreements/treaties about sharing power of AI

The risks are driven by the possibility that some nuclear actor, at some point, may not perceive better options than initiating nuclear war. An obvious mitigating strategy is to work to ensure that there always are such options, and they are clear and salient.

Since the potential benefits from AI are large, it seems likely that there should be possible distributions of benefits and of power which look robustly better to all parties than war. The worry is that things may move too fast to allow people to identify these (or if there are differing views about what is fair, that this difference of views will lead to obstinacy from people each trying to hold out for what they think is fair and thereby walking into war). Working early on possible approaches for such distributions, and how best to reach robust agreement on that, could thereby help to reduce risk.

I say “sharing power” rather than just “sharing benefits” because it seems like a good fraction of people and institutions ~terminally value having power over things. They might not be satisfied with options which just give them a share in the material benefits of AI, without any meaningful power.

Differential technological development

Strong and trusted AI tools targeted at the right problems could help to change the basic situation in ways that reduce risks of (rational or irrational) initiation of nuclear war. This could include both development of the underlying technologies, and building them out so that they are actually adopted and have time to come to be trusted.

To survey how AI applications could help with the various possible reasons for war:

- Irrational decision-making

- Good AI tools could help people to make better sense of the world, and make more rational decisions.

- AI systems could help people to negotiate good mutually-satisfactory agreements, even given complex values and private information.

- Misaligned decision-makers

- AI could potentially give new powerful tools for democratic accountability, holding individual decisions to higher standards of scrutiny (without creating undue overhead or privacy issues)

- National pride

- AI-driven education, persuasion, or propaganda could potentially (depending on how it is employed) either increase national pride as a factor in people’s decision-making, or decrease it

- Private information

- AI-empowered surveillance or the equivalent of trusted-arms-inspectors might enable credible conveyance of certain key information without giving up too much strategically valuable information.

- AI empowered espionage could decrease private information (however, AI-empowered defence against espionage could increase the amount of private information).

- NB I'm particularly concerned here with espionage which gives people a sense of where capabilities have got to; espionage which steals capabilities would have different effects.

- Commitment issues

- AI-mediated treaties might provide a useful new type of commitment mechanism. If a mutually-understood AI agent could act as a fair arbiter, and be entrusted with sufficient authority for enforcement mechanisms, this could allow for commitments even in some situations where there is currently no higher authority that can be used

- NB we are currently a long way from a world where these could be sufficiently trusted for this to work.

- AI-mediated treaties might provide a useful new type of commitment mechanism. If a mutually-understood AI agent could act as a fair arbiter, and be entrusted with sufficient authority for enforcement mechanisms, this could allow for commitments even in some situations where there is currently no higher authority that can be used

- Issue indivisibility

- Maybe AI could help make indivisible issues less frequent, via making it more possible to explore the full option space and find clever deals

- This is based on the idea that often “indivisible” issues are not truly indivisible, merely hard-to-divide

- Maybe AI could help make indivisible issues less frequent, via making it more possible to explore the full option space and find clever deals

By default, I expect the increases in risk to occur before we have strong (& sufficiently trusted) effective tools for these things. But accelerating progress for these use-cases might meaningfully shrink the period of risk.

I am uncertain which of these are the most promising to pursue, but my guesses would be:

- AI-mediated arms inspections

- Automated negotiation

- Tools for democratic accountability

What about an AI pause?

If AI takeoff is a driver of risk here, would slowing down or pausing AI progress help?

My take is that:

- Things which function as persistent slow-down of AI progress would be helpful

- (But it is hard to identify actions which would have this effect)

- Things which function as temporary pauses to AI progress are more fraught

- It is quite possible for them to be actively unhelpful, by making the period after a pause (or if some states work on AI secretly during a pause) more explosive and destablizing

- But if the pause were well-timed and the the time were used to help get people on the same page about the strategic situation, a pause could definitely be helpful

Closing thoughts

What about non-nuclear warfare?

This analysis is about all-out war. Right now this probably means nuclear, although that could change with time. (Bioweapons could potentially be even more concerning than nuclear.)

How big a deal is this?

On my current impressions, destabilizing effects from AI takeoff leading to all-out global war are very concerning. My credal resilience on any particular estimates of absolute risk isn't high, but I think it's fair to say that, having thought about all of them for some time, it's not clear to me which are the biggest risks associated with AI, between risk from misaligned systems, risk of totalitarian lock-in, and risk of nuclear war.

Given this, it does seem clear that each of these areas deserves significant attention. I think the world should still pay more attention to misaligned AI, but I think it should pay much more attention than at present to risks of things ending in catastrophe for other reasons as people navigate AI takeoffs. I'm less confident that any of my specific ideas of things to do are quite right.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Eric Drexler, who made points in conversation which made me explicitly notice a bunch of this stuff. And thanks to Raymond Douglas, Fynn Heide, Max Dalton, and Toby Ord for helpful comments and discussion.

- ^

There is also a risk of nuclear war initiated deliberately by misaligned AI agents. But as the risks of misaligned AI agents receive significant attention elsewhere, and as the mechanisms driving the risk of nuclear war are quite different in that case, I do not address it in my analysis here.

- ^

Obviously nuclear war is a terrible outcome on all normal metrics. But is there a galaxy-brained take where it’s actually good, for stopping humanity before it goes over the precipice?

This is definitely a theoretical possibility. But it doesn’t get much of my probability mass. It seems more likely that:

1) Nuclear war would not wipe out even close-to-everyone.

2) While it would set the world economy back quite a way, it wouldn’t cause the loss of most technological progress.

3) In the aftermath of a nuclear war, surviving powers would be more fearful and hostile.

4) There would be greater incentives to rush for powerful AI, and less effort expended on going carefully or considering pausing.

JuanGarcia @ 2024-06-12T09:11 (+12)

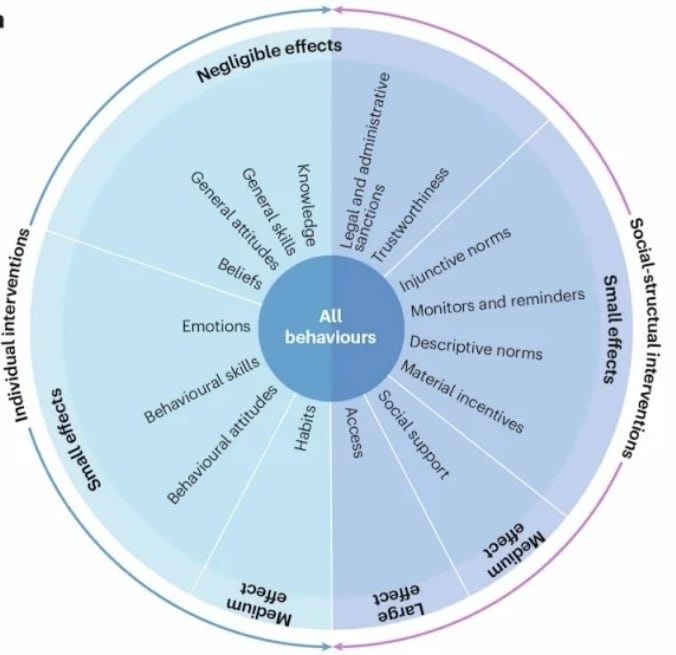

Interesting post. Just a quick comment on the effectiveness of "research and dissemination" and "Spreading “we’re all in this together” frames" type interventions. These sound similar to interventions that policymakers try time and again in response to disasters because they're intuitive, despite the fact that they don't work very well or at all.

The source I linked describes a comparison of interventions for pandemic response in the general public, so it's not directly applicable, but I worry a similar issue may be at hand here. The interventions aimed at changing minds generally have negligible effects, especially compared to other interventions such as providing social support and tapping into individuals’ behavioral skills and habits as well as removing practical obstacles to behavior.

I don't know what the equivalent on the "nuclear war prevention" area is of these other interventions that work well for pandemic response, but I do worry that the "knowledge and beliefs" type interventions proposed would also be negligible like they are in this other field.

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-06-12T10:06 (+4)

Thanks, I think there's a real question here about how effective this work can be. Although note that in the pandemic case you're mostly hoping to get behaviour change from the general population, while in the nuclear war case you're mostly hoping to get behaviour change from a small number of key decision-makers (who I think are typically more likely to be somewhat receptive to arguments).

Linch @ 2024-06-11T22:19 (+2)

Interesting post! I think you have a formatting issue. I think reasons 4,5,6 should be under "irrational reasons to go to war"

Owen Cotton-Barratt @ 2024-06-11T22:36 (+2)

Ah, thanks! Fixed (-ish; looks like the forum won't allow numbered lists to have non-list text in the middle, so it's not the prettiest, but it should be more readable).

Edit: also fixed another issue (a couple of minor bullets had been dropped under "differential technological development").

SummaryBot @ 2024-06-12T12:51 (+1)

Executive summary: The rapid development of powerful AI could increase the risk of nuclear war by disrupting the current equilibrium and introducing new destabilizing factors related to commitment problems, private information, irrational decision-making, misaligned leaders, and national pride.

Key points:

- Rational reasons for war include commitment problems, private information with incentives to misrepresent, and issue indivisibility. AI takeoff could exacerbate commitment problems and increase private information.

- Irrational reasons for war include mistakes by stressed decision-makers, misaligned leaders, and national pride. AI takeoff could make the situation harder to understand and increase the influence of these factors.

- Strategies to reduce risk include research and dissemination to improve understanding, spreading unifying frames, agreements on sharing AI benefits and power, and differential technological development of AI applications that address the underlying reasons for war.

- A well-timed AI pause could help if used to get alignment on the strategic situation, but a poorly timed pause could be destabilizing.

- The risks of nuclear war from AI takeoff disruption deserve significant attention alongside risks from misaligned AI systems and totalitarian lock-in.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.