Reflections on Compatibilism, Ontological Translations, and the Artificial Divine

By Mahdi Complex @ 2025-05-07T12:17 (–3)

[cross-posted from LessWrong]

This essay explores the concept of compatibilism beyond its traditional domain of free will, proposing a broader methodological approach I call 'Transontological Compatibilism.' I argue that this approach, identifying functional analogies across seemingly incompatible ontologies, can help us navigate philosophical, cultural, and linguistic divides. Ultimately, I will examine whether it can help us rethink our language and conceptual frameworks surrounding transformative artificial intelligence, perhaps even justifying a cautious embrace of religious vocabulary.

1. Compatibilism and Free Will

Believers in libertarian free will consider choices to be ontologically fundamental to reality and not entirely bound by the traditional deterministic chain of cause and effect. This view implies a mind-body dualism in which an immaterial and irreducible 'self' is the source of "choices." These choices are thought to be the product of a special kind of freedom that allows for a unique capacity for self-determination.

In this ontology, a choice is a cause, uncaused by any cause outside of this 'self', making this 'self' ultimately responsible for the choice. Central to this view is the idea that, if one were to go back in time, there would be a meaningful sense in which one could have chosen differently, regardless of the identical material circumstances.

This is a subjectively parsimonious ontology that jibes well with our experience of choice, responsibility and regret. I suspect the majority of people, at one time or another, perceive reality through the lens of this ontological framework. But, since physics tells us that we are in a physical, causally closed universe, obeying inviolable natural laws, this ontology cannot be true. If all our choices are determined by material causes ultimately outside of our control, how could we be said to be "free" to choose differently? When faced with this dilemma, people seem to adopt one of two strategies.

The first one, adopted by free will anti-realists, rejects the notion of free will entirely. If the old understanding of "free will" isn't compatible with a correct physical ontology, why keep it around in the first place? Free will, in that conceptualization, is nothing more than an illusion. Anti-realists argue that our subjective experience of making choices is not evidence of libertarian free will, but rather an emergent property of the complex causal processes in our brains, determined by physical causes ultimately beyond our control. They maintain that recognizing this fact is crucial for developing a more accurate, enlightened, and scientifically grounded understanding of human decision-making, responsibility, and ethics.

The second strategy is called compatibilism. Compatibilists, just like free will anti-realists, strongly reject the notion of "libertarian free will." However, they observe that, in their materialistic ontology, there is still a useful and intelligible phenomenon that maps quite cleanly on the old concept of free will. This phenomenon could be described as the mental algorithm that is conscious, deliberate decision making. For compatibilists, 'free will' refers to the capacity for sober reflection and unencumbered agency.

Despite their shared rejection of libertarian free will, compatibilists and free will anti-realists often find themselves at odds. This tension arises primarily from a disagreement over the definition and use of the term "free will." For anti-realists, compatibilists' insistence on preserving the language of free will, even in a modified form, seems to lend undue credence to the libertarian view. Anti-realists argue that by using the same terminology, compatibilists risk perpetuating the confusion and misconceptions surrounding free will, inadvertently granting a superficial victory to those who hold a fundamentally flawed understanding of human agency.

They might argue that by using compatibilist language, one lends credence to the common retributive belief that perpetrators deserve punishment, independent of considerations of deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation. Thereby, compatibilists might be hindering reforms to make the criminal justice system more compassionate.

On the other side, compatibilists argue that their view allows us to preserve the conceptual framework that underlies our notions of moral responsibility, desert, and the justification for punishment, allowing us to retain important moral and social concepts that shape our practical and legal systems. Their perspective describes a form of freedom that is still meaningful, while guarding against the type of detrimental fatalism that sometimes follows a loss of belief in free will.

This disagreement between compatibilists and anti-realists is ultimately more semantic than substantive, as both positions acknowledge the deterministic nature of the universe and the absence of libertarian free will.

The debate between compatibilists and free will anti-realists highlights the challenges that arise when our understanding of the world shifts due to scientific or philosophical advances. As we grapple with such changes, we are often forced to reevaluate and redefine concepts that were once central to our worldview and deeply ingrained in our language and discourse. In the following sections, I will explore how the compatibilist approach can be applied more broadly as a strategy for navigating these ontological transitions and facilitating communication across different frameworks of understanding.

2. Towards a More General Definition of Compatibilism

A note on terminology:

As I developed the ideas presented in this piece, I realised that the term "compatibilism" had taken on a new meaning for me, drifting beyond its traditional use in academic philosophy where it is strictly associated with free will. In this piece, I often use "compatibilism" in a broader sense. However, this usage deviates from the conventional definition and could potentially lead to confusion. I welcome suggestions for a more precise term or practice that might better capture this expanded concept. To distinguish this broader concept when necessary, I will call it 'Transontological Compatibilism', though I will often use the shorter 'compatibilism' when the context makes my intended meaning clear.

I define Transontological Compatibilism as being a methodological approach that identifies correspondences between entities, elements, or structures in disparate ontologies that perform analogous functional roles. By establishing these correspondences, individuals adhering to different ontologies can align on a common referent. This alignment, in certain contexts, enables effective communication, improved understanding, cooperation, and harmonious coexistence despite significant differences in worldviews.

Let’s go through some examples:

a. Newtonian and Einsteinian Gravity

First, a simple, straightforward and uncontroversial case.

Imagine two physicists, Dr. Newton and Dr. Einstein, working together on a project to launch a satellite into orbit. Dr. Newton is deeply committed to the Newtonian view of gravity as an instantaneous force acting between objects. In contrast, Dr. Einstein has fully embraced the Einsteinian ontology of gravity as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime.

Despite their different ontological perspectives, Dr. Newton and Dr. Einstein are able to collaborate effectively on the satellite project. For Dr. Newton, this means applying his established equations, which he views as a true representation of gravity as an instantaneous force. Dr. Einstein, on the other hand, while fully committed to his understanding of gravity as spacetime curvature, adopts a compatibilist approach. He recognizes that for calculating the satellite's trajectory, Newtonian mechanics offer an effective and sufficient model, and that introducing the complexities of his own framework would offer no significant advantage to the project's success. By focusing on the functional equivalence of the calculations in this context, Dr. Einstein can seamlessly work alongside Dr. Newton. This enables them to communicate, collaborate productively, and ultimately, successfully launch the satellite into orbit.

It's important to note that the Newtonian and Einsteinian gravity example differs from the other examples discussed in the clarity of the ontological boundaries. In the gravity example, there is a well-defined domain where Newtonian gravity is a valid approximation and clear limitations beyond which it breaks down. This makes it easier for physicists to agree on when a compatibilist approach is appropriate. In contrast, the boundaries between different ontologies in other areas such as free will are more ambiguous and contentious, leading to persistent disagreements and challenges in applying compatibilism effectively.

b. Bacteria and Bad Spirits

In Kwame Anthony Appiah's Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, he recounts an anecdote of a medical missionary in a remote village. The missionary observes that many babies are dying from diarrhea caused by drinking untreated well water. When the missionary explains that boiling the water will kill the invisible bacteria that make the children sick, the villagers do not change their behavior. However, when the missionary instead tells them that boiling the water will drive out the evil spirits that cause the illness, the villagers begin to boil their water and the babies stop dying.

Some might view the medical missionary's approach as deceptive, since using evil spirits as an explanation is incompatible with a correct scientific understanding of the world. It could be argued that the missionary is prioritizing the goal of changing the villagers' behavior over the importance of conveying accurate information, essentially telling a well-intentioned lie to achieve a desired outcome. However, I believe this assessment isn’t entirely fair to the missionary, and fails to capture some of the nuance of the situation.

Imagine a prosecutor who rejects libertarian free will but still needs to argue, in front of a jury holding a traditional libertarian view, that the accused acted with "free will." Can the prosecutor truthfully assert that the accused acted with "free will" without misleading the jury? Does honesty demand a philosophical detour, first requiring the prosecutor to dismantle the jury's libertarian assumptions and explain the nuances of compatibilist free will? Or, in the courtroom's practical reality, can differing conceptions of "free will" still exhibit sufficient functional overlap to serve the needs of the legal proceedings?

In the same way, does the missionary, in this context, have to first explain our modern scientific understanding of the origin of disease in order to communicate honestly? Or is it justifiable to adopt a compatibilist approach, which would recognize that in the villager’s ontology, "bad spirit" simply is the name given for "that which causes sickness." And so, rather than lying, the missionary is merely performing an ontological translation. Just as "killing bacteria," in modern parlance, simply means "removing the thing that makes you sick," so does "removing bad spirits" correspond to the same meaning in the villager’s ontology.

Of course, "bacteria" points to a much deeper and important scientific understanding of what is going on, and in many cases, that underlying understanding, and the adoption of the right explanatory framework will be important, but in the context that missionary finds herself in, insisting on using our modern scientific ontology at the cost of actually getting your point across seems unnecessary. Isn’t the missionary succeeding in making the villager less wrong by inculcating a belief that "pays rent in anticipated experience"?

c. Good and Evil

As a moral anti-realist, I find most discussions of morality to be subtly wrong. Since I do not think "good and evil," are ontologically basic, natural categories, I am tempted to strike them from my vocabulary, as well as many of the concepts commonly used in moral deliberation. Instead of thinking "action X is evil" I would say "action X is very negative in my preference ordering," or "I think that action X is very negative according to some almost universally accepted set of preferences."

But then, by doing so I am creating a big ontological language barrier between myself and the majority of discourse arguing over how we should act. And so, I think like most moral anti-realists, I continue to use language that seems to imply that "good" and "evil" are actually real properties that are "out there," even though, when pressed, I will readily admit that my concept of "good" points to a much more fuzzy, subjective and emergent category in my ontology than it is in many other people’s ontology.

In theory, a community of moral anti-realists could choose to avoid using terms like "moral," "good," and "evil" altogether. Instead, they could develop a novel framework for collective decision-making and discourse based solely on concepts such as individual and shared preferences, utility functions, and optimization. However, by adopting this approach, they would effectively isolate themselves from the vast corpus of literature and the numerous individuals who continue to rely on the conventional moral ontology that has long been ingrained in our culture. In most situations, the price of this isolation far outweighs any potential benefits gained from abandoning the traditional moral language.

d. The Soul

My mother, like many people, holds a traditional worldview that places deep importance on the concept of the Soul. For her, it signifies something essential and perhaps eternal about a person. I used to reject this concept entirely, convinced by my own materialist understanding that souls simply did not exist. This outright dismissal, however, often created tension and misunderstanding between us, shutting down potentially meaningful conversations.

However, I have since realized that my rigid rejection was often missing the point. While I couldn't accept the metaphysical baggage, I started to consider what my mother was actually pointing to when she spoke of it. It seemed to represent the undeniable uniqueness of an individual's inner world: their consciousness, self-awareness, personal history, core values, the deep-seated sense of dignity inherent in being human, and their capacity for profound emotional experience, moral reflection, and connection. These aspects of personhood felt undeniably real and important, even if I understood their origins differently—seeing them as emergent properties arising from the complex interplay of mind, biology, and environment, rather than a distinct, immaterial substance.

By adopting this more compatibilist perspective, focusing on the functional role the concept played for her and the human qualities it referred to, I could engage with the idea of the Soul without compromising my own worldview or invalidating hers. It allowed me to acknowledge and affirm the profound human qualities we both valued, even if we disagreed on the underlying metaphysics. This reframing allows the conversation to continue past the mention of the 'Soul', showing her that my skepticism about the traditional view doesn't mean I fail to cherish the very human essence she associates with the term.

e. The Sacred

The sociologist Max Weber argued that modernity, through science, bureaucracy, and the pursuit of rational material ends, has led to the "disenchantment" of the world. The rise of scientific rationalism and decline of religion has weakened traditional sources of meaning, leading to what he saw as alienation and existential uncertainty.

This disenchantment poses a challenge: how do we preserve meaning and the profound experiences traditionally associated with religion while embracing a scientific worldview? I encountered this tension personally as a child. Having taken religion seriously, I found in the concept of 'the sacred' something important—a particular emotional attitude that combined profundity, awe, and veneration. After losing my faith, I found myself struggling to find an equivalent concept in mainstream secular culture. The mainstream secular worldview seemed to lack a vocabulary for this kind of experience, as if in rejecting religious metaphysics we had accidentally discarded something valuable about how to relate to the profound. Here too, a compatibilist approach might offer a solution, as is argued by Eliezer Yudkowsky in his post "The Sacred Mundane."

Yudkowsky begins by identifying what he sees as distortions that religion has introduced to our experience of the sacred: the insistence on mystery, the retreat to private experience, the separation of sacred from mundane, and the emphasis on faith over evidence. These are not inherent to the experience of the sacred itself, but rather defensive adaptations that have evolved to shield religious beliefs from criticism. Instead, Yudkowsky argues for finding the sacred in the "merely real" — in space shuttle launches, in the birth of a child, in looking up at the stars while understanding what they truly are. This is sacredness without artificial barriers, "believable without strain," and shareable among all observers. The experience remains profound, but it is now grounded in reality rather than mystery, shared rather than private, connected to rather than separate from the mundane world.

Yudkowsky's description is a compatibilist one. He examines the functional role of 'the sacred' in the context of religious ontology and finds its closest equivalent in his own rationalist one. This allows him to successfully translate and retain the essential aspects of the sacred still meaningful in his worldview.

Many of the examples above can be understood as translating core concepts traditionally rooted in religious ontology into a more secular scientific one. The next section explores how this process of ontological translation reappears in discussions surrounding artificial intelligence, marked by the use of seemingly religious language. This recurrence prompts a deeper examination of the conceptual frameworks used to discuss this transformative technology, and the complex choices involved in employing such historically loaded terms.

3. The Artificial Divine

a. The Machine God

When reading about the future of AI, one will regularly encounter another use of a word that could be interpreted as an ontological translation of an element of religious ontology: God.

Ray Kurzweil, in The Singularity is Near, writes: "Once we saturate the matter and energy in the universe with intelligence, it will 'wake up,' be conscious, and sublimely intelligent. That's about as close to God as I can imagine." In his book The Master Algorithm, computer science professor Pedro Domingos declares that "any sufficiently advanced AI is indistinguishable from God." Former Google executive Mo Gawdat states in an interview: "The reality is, we're creating God." And Tim Urban, concluding the first part of his popular series on the AI Revolution, asks: "if an ASI comes to being, there is now an omnipotent God on Earth—and the all-important question for us is: Will it be a nice God?"

These invocations might sound like hyperbolic metaphors. But seriously consider what life for biological humans would be like if we built a Superintelligence roughly aligned with human values. What if we, as Scott Alexander put it in "Meditations on Moloch", "install a Gardener over the entire universe who optimizes for human values"? How will future humans speak of such an entity? Would it really be so strange for someone born in such a world to call this "Gardener" God, and mean it as literally as the convinced theists do today?

A large swath of humanity has millennia-old cultural traditions dealing with humans' relationship with a being vastly more powerful and intelligent than themselves. Do we expect people of the future not to reappropriate the language from those traditions when actually faced with such an entity? In the same way Democritus' atom found itself a new meaning in 19th century physics, might 'God' be similarly repurposed in the future?

Perhaps the implied expectation of a 'Singleton-like' entity—a single decision-making agency at the highest level—is wrong. Maybe we have become too caught up in early singularitarian speculation that tried to imagine a single maximally powerful superintelligence, inadvertently making it maximally God-like. The future might instead resemble something closer to a pantheon of gods, or, as depicted in Iain Banks' "Culture" novels, Superintelligences will take the form of numerous benevolent "Minds" with limited ambitions coexisting, rather than a single almost omnipotent entity. Or maybe the future will turn out weirder still, in a way we cannot imagine today.

But before I continue exploring the choice to use compatibilist religious language when talking about AI, I want to describe some of the past attempts at such a compatibilist translation. Indeed, modern technologists are by no means the first ones attempting to import God into a more secular and scientific worldview.

b. Primer Primer

In "A Primer on God, Liberalism, and the End of History", I examined how some Enlightenment philosophers grappled with the concept of 'God', which was central to the worldview of medieval Christendom, by translating this foundation of Christian thought into their own philosophical frameworks. Baruch Spinoza redefined God as the totality of material reality (deus sive natura). This ontological translation would be embraced by many scientists, probably most famously Albert Einstein, attempting to express a more spiritual dimension to their scientific worldview, or trying to minimize the perceived distance between their worldview and that of theists.

Many others would endorse similar views. The Christian existential philosopher Paul Tillich, argued that God was not a being, but "the ground of being", preceding any subject-object distinction. The popular philosopher Alan Watts would equate God with fundamental existence, or, while translating between Eastern and Western philosophy, he would equate God with 'Tao' or 'Brahman'.

Other enlightenment philosophers took a different approach. Hobbes proposed ending religious conflicts through the establishment of a "Kingdom of God by Nature," governed by a human deity—the Leviathan. Rather than focusing on the spiritual or metaphysical aspects of God, Hobbes tried to translate the political functions God played within the ontology of medieval Christian political-theology. He reasoned that if people could not agree on the will of the mysterious and distant God of Christian theology, a human God would need to take on the role.

Later, Hegel attempted a more ambitious translation. In his panentheistic philosophy, he identifies God with 'Absolute Spirit', manifesting itself historically in the sensible, rational and ethical State. For Hegel, the rational State represents "the march of God on earth," the progressive realization of divine reason and human freedom, and thus embodies the Christian ideal of human equality before God in secular political institutions. Hegel thus attempts a coherent compatibilist translation that integrates both the metaphysical and political dimensions of the Christian conception of God. He finds God within the unfolding human historical process in the world ("deus sive homo").

c. The God of Rationalists

These historical attempts at ontological translation remained largely abstract, metaphorical or unsatisfying, and therefore never broadly caught on. They lacked a concrete referent that could truly fulfill the functional role of the divine in human experience. However, an Artificial Superintelligence may constitute a much more compelling compatibilist translation of 'God'—an entity with genuine power, intelligence, and agency far beyond human capacity, capable of radically transforming the environment and the human condition.

However, this is not a translation that has gained much traction in the rationalist community, the group that was among the earliest to take AI and singularitarian ideas seriously.

The 'God' of LessWrong is either inseparable from the Abrahamic theistic ontology and thereby better abandoned entirely, or, when a translation is attempted, it tends to take on a Lovecraftian turn.

When Yudkowsky tries a compatibilist translation through the lens of Darwinian evolution, he declares God to be "Azathoth, the blind idiot God burbling chaotically at the center of everything."

Or when Scott Alexander starts to wax poetic, in the same essay he calls for installing "a Gardener over the entire Universe", he explains that he means by that a permanent victory of Elua, "the god of flowers and free love and all soft and fragile things. Of art and science and philosophy and love. Of niceness, community, and civilization", and the defeat of the "alien deities," "Cthulhu, Gnon, Moloch". Alexander summarizes his position by declaring, "I am a transhumanist because I do not have enough hubris not to try to kill God."

And so, when we analyze his metaphorical framework, Alexander seems to think of 'God' as the collective of all alien deities that mean humanity harm, all except Elua. It is a curious ontological translation, perhaps influenced by the new atheist anti-theism popular at the time of his writing. While previous compatibilist strategies focused on finding positive analogies or functional equivalents for religious concepts within a naturalistic framework, Alexander's Promethean approach instead sets up an opposition that casts divinity itself as antagonistic to human flourishing. The result is a framing that, perhaps unintentionally, becomes maximally alienating to those with religious sensibilities.

What explains this aversion to "God" among rationalists? Why do many reject the concept entirely, or, when attempting any translation, seem unwilling to find a positive compatibilist equivalent, instead framing "God" exclusively in terms of harmful cosmic forces? Is it a kind of intellectual immune response, a rejection of anything that carries the scent of irrationality or superstition? An effort to make their ontology as incompatible with that of religion as possible?

Or, could it be a strategic move to keep the conceptual space clear for an entirely scientifically grounded, God-like entity, a Friendly Superintelligence, ensuring this novel concept isn't preemptively saddled with the historical and ontological baggage of traditional theism?

These explanations do have some merit. But I think there is another layer to this explanation, which rationalists may not be fully conscious of.

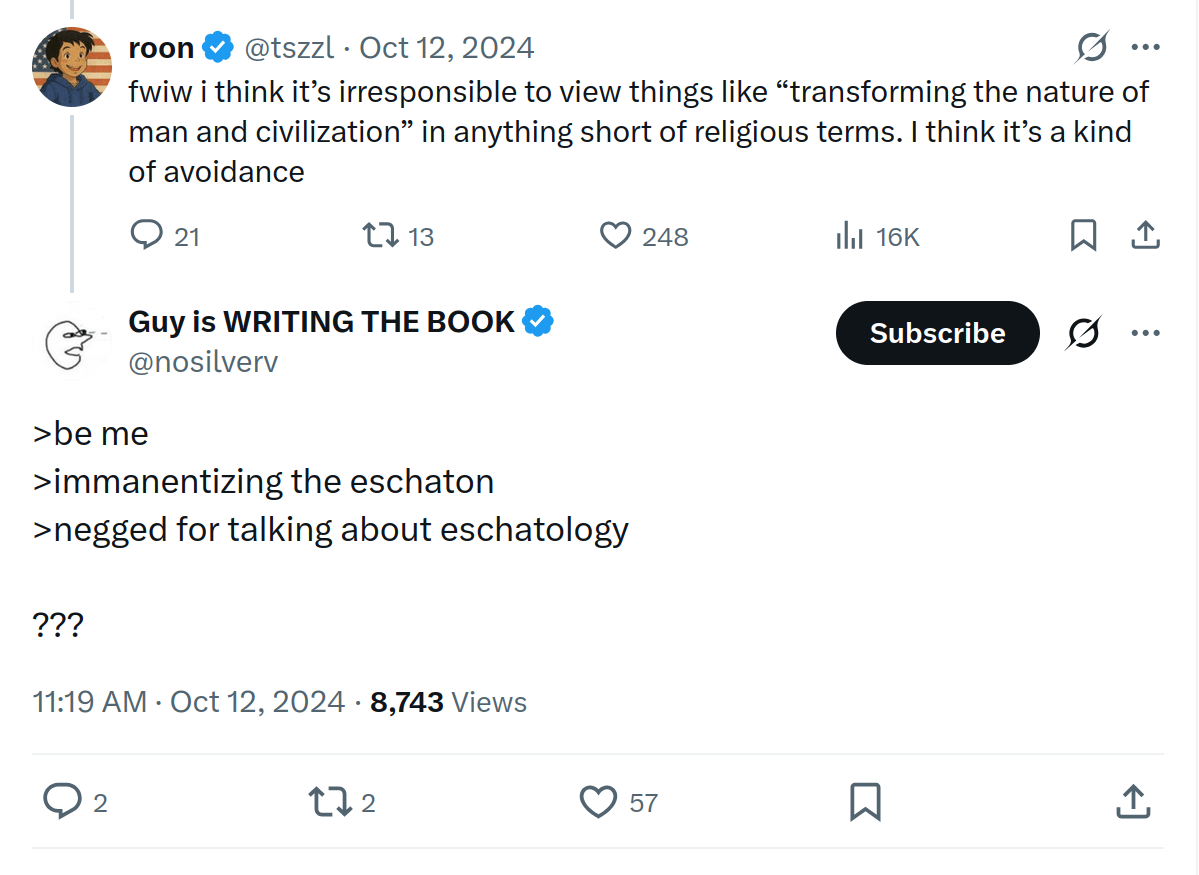

d. The Return of Eschatological Questions

Indeed, there is another term of religious ontology that rationalists will conspicuously avoid: that of 'eschatology.' From a compatibilist perspective, rationalists are centrally preoccupied with eschatological questions, or, as they call it, with the future of humanity. When the Christian reflects on the prophesied Apocalypse, and the rationalist speculates on the shape of an upcoming technological singularity, they are asking themselves the same question: what is to become of humanity?

This overlap in eschatological concerns is an inconvenient one for rationalists. Finding themselves asking fundamentally similar questions to religious believers and apocalyptic cults, rationalists will instinctively seek to do whatever they can to distinguish their futurism from religious prophecy, even while addressing questions traditionally confined to religious domains.

But maybe the more interesting question is, why does the rest of modern secular society have such a disinterest in these questions? After all, isn’t the question of the destination of humanity’s story not a really interesting question? One of the most interesting and important questions one can ask? And yet, it is a question that seems to receive very little attention in mainstream secular culture. Why is that?

As I argued in my Primer, the answer lies in how classical liberalism deliberately sidelined eschatological thinking. Two distinct approaches emerged to handle humanity's persistent questions about ultimate destiny in the cosmos, which had caused so much bloodshed in pre-Enlightenment Europe. The Anglo-American liberal tradition, following Locke, chose intellectual compartmentalization—relegating questions of humanity's ultimate end to the private sphere while creating a politics focused solely on maintaining peace and facilitating commerce. This approach didn't reject eschatological questions outright but deemed them too dangerous, unknowable and divisive for public discourse. By pushing these questions out of politics, Locke's tradition created a secular society where people could peacefully coexist despite holding radically different views.

The continental tradition, from Hegel to Fukuyama, took a different approach. Rather than compartmentalizing eschatological questions, they attempted to answer them definitively. Hegel declared that history was reaching its culmination in the modern rational state, while Fukuyama later proclaimed liberal democracy as "the final form of human government." Both effectively declared "mission accomplished" on humanity's historical journey. By announcing that we had already arrived at our destination, they rendered further eschatological speculation unnecessary. Why contemplate humanity's ultimate destiny when we're already living it? This approach didn't banish eschatology from politics so much as declare it resolved.

Both traditions succeeded in creating a politics unburdened by cosmic questions, allowing modern secular society to focus on immediate practical local concerns rather than grand questions about the destiny of humanity. This explains why mainstream secular culture shows such disinterest in humanity's long-term future—our intellectual traditions have either trained us to consider such questions private matters or convinced us they've already been answered.

Against this backdrop, rationalists' preoccupation with humanity's long-term trajectory appears almost transgressive. By seriously engaging with questions about the possibility of a technological singularity and the potential transformation of human civilization, they find themselves inadvertently reopening eschatological questions that liberalism worked so hard to contain. Their avoidance of religious-sounding language reflects an implicit recognition of this boundary-crossing. They are asking questions that, in their previous incarnation, our intellectual tradition deemed either too divisive for public discourse or already settled.

Yet this apparent transgression should not lead us to dismiss the importance of these questions. The rationalist approach to humanity's future differs fundamentally from religious eschatology. It is grounded not in revelation or faith, but in scientific understanding and technological forecasting. Perhaps our scientific and technological capabilities have finally advanced to a point where reopening questions about humanity's ultimate destiny has become unavoidable, and our materialist ontology has now matured sufficiently to engage meaningfully with these once-religious questions. When we stand at the threshold of creating entities vastly more intelligent than ourselves—entities capable of transforming the foundations of human civilization—we cannot help but confront questions about our collective future.

This creates a troubling tension. Our liberal intellectual framework lacks the vocabulary and conceptual tools to properly address these questions, having deliberately sidelined them for centuries. Yet the accelerating development of transformative technologies demands that we confront them nonetheless. The rationalist community's unease with eschatological language reflects this broader cultural predicament—we must now grapple with questions our intellectual tradition has taught us to avoid, using conceptual frameworks ill-suited to their magnitude.

e. God is Great?

The present essay is not my first attempt at wrestling with the arguments I explore here. In an earlier piece titled "God is Great," I sought to articulate the profound implications of transformative artificial intelligence through a compatibilist lens, deliberately invoking religious language.

My motivations for writing it were manifold. Despite having gone through my own new-atheist phase, I had found an appreciation for those various historical ontological translations of 'God' I described above. At the same time, I was deeply immersed in exploring transhumanist and longtermist ideas, and was increasingly convinced that the development of AGI was likely to occur in my lifetime. I found myself forced to accommodate a new 'God-like' entity in my ontology. I felt compelled to communicate the magnitude of what was coming to an audience that included both secular intellectuals and religious friends. I was troubled by the profound indifference of mainstream intellectual discourse within politics, media, and academia toward these developments. I had come to see liberalism's origin as a strategy to avoid eschatological questions as one central reason for this blindspot.

In "God is Great," I began by examining Spinoza's conception of God, juxtaposing scripture suggesting a panentheistic deity with Yudkowsky's reverent descriptions of "mere reality." Through this provocative parallel, I attempted to establish an ontological translation of 'God' in the rationalist worldview. I then recognized that Spinoza's impersonal, mathematical God seems to fail to capture the moral agency and purposefulness that religious traditions associate with divinity.

I then turned to Durkheim and Hegel, who offered a more human-centered conception of God. For Durkheim, God was society writ large, evident in the collective effervescence that binds communities together through shared rituals, religious experiences, and moral ideals. For Hegel, God was the unfolding of Absolute Spirit through history, manifesting itself concretely in human institutions and the rational state.

Building on this understanding of God, I reframe effective altruism as the question of how one might "embody a compassionate, all-loving, benevolent God."

I then ask how Spinoza's impersonal God and Durkheim's moral human God can be reconciled, and explain that human agency, morality, and consciousness were themselves emergent phenomena arising naturally from the lawful impersonal structure of the universe. In this view, humanity's growing understanding and mastery of natural laws allowed us to progressively imbue the universe with human purposes, effectively merging Durkheim's God with Spinoza's.

I conclude the essay discussing the Singularity as the point where Spinoza's impersonal God and Durkheim's human-centered God might converge. I argued that through AGI's recursive self-improvement, the universe could become increasingly imbued with human agency and purpose, reflecting humanity's potentially cosmic ambitions. The narrative has resonances with Hegel's philosophy, except that instead of ending human History with the modern state, I suggest that humanity's trajectory points toward a technological transformation. This transformation, I proposed, could ultimately merge reality's lawful structure with our highest moral ideals, provided we sufficiently grasp how agency operates within those immutable laws.

My embrace of religious and eschatological language in "God is Great" was deliberate and intentionally provocative, though, admittedly, ended up making it a significantly more confusing or threatening-seeming post than I had expected or intended. Unlike many who strain to distance their futurist speculations from religious frameworks, I wanted to highlight the profound break such thinking represents from classical liberalism's containment of eschatological questions. This linguistic choice was meant to convey how transformative AI was going to fundamentally disrupt the intellectual settlement underpinning modern secular society. Where rationalists often present their eschatological speculations in sanitized technical language, I felt that only religious vocabulary could adequately convey both the magnitude of the transformation ahead and its radical departure from liberalism's boundaries on cosmic thinking.

f. The Perils of Religious Framing

But, should our discussions of the future of AI really sound more religious? Is there a safe way to practice such ontological promiscuousness? In his essay "Machines of Loving Grace", Dario Amodei warns against grandiosity, and viewing "practical technological goals in essentially religious terms."

The concern about religious language in AI discourse is well-founded. For serious researchers and policymakers, adopting religious language risks derailing precise technical communication, undermining credibility within expert communities, and leading influential figures to dismiss crucial safety and governance discussions as irrational or unserious speculation rather than grounded analysis. Such a linguistic choice might alienate the very individuals whose rigorous, skeptical approach is most needed.

Simultaneously, while such language may repel some, it might also energize uncritical enthusiasm elsewhere. Framing AGI development in religious or eschatological terms can easily fuel techno-optimistic fervor and messianic narratives, obscuring profound risks and complex ethical trade-offs. History warns against the dangers of quasi-religious zeal clouding judgment and justifying recklessness. Rather than fostering the necessary caution and humility, such framing might inadvertently encourage the blind faith, sense of inevitability, and overconfidence we must avoid when dealing with potentially world-altering technology.

Furthermore, such compatibilist religious language risks alienating religious individuals themselves. For many believers, "God" holds a specific sacred meaning deeply embedded within their particular ontological framework. Applying this term to a technological entity can thus feel profoundly jarring or dissonant. Doing so, however powerful the entity, may seem reductive, trivializing, or even offensive, potentially evoking scriptural warnings against worshipping false gods or idols. Such appropriation may provoke a backlash from religious communities rather than fostering mutual understanding.

g. When Secular Vocabulary Falls Short

With all this being said, I'd nevertheless like to offer a defense of such compatibilist use of religious language. Creating intelligences far beyond human capacity isn't just a technological challenge; it's a profound challenge to nearly all existing human worldviews. Long-held assumptions, whether rooted in religious doctrine or in secular political thought, may prove inadequate. Whether one operates from a framework of established political theory, technological development, or traditional religious faith, the emergence of truly autonomous, superior non-human agency is likely to introduce realities that fit awkwardly, if at all, within our inherited ontologies. While religious language carries risks when applied to technology, purely secular or technical vocabularies may also fall short in capturing the existential weight and transformative potential of the non-human intelligent entities we are creating.

Discussing AI solely in terms of technological progress, commercial competition, or geopolitical rivalry risks trivializing the undertaking. Crucially, it risks forcing solutions into paradigms conceived for an age when intelligence was exclusively biological and human-scale. Given the potential to fundamentally alter humanity and civilization, perhaps our language must evolve to reflect the gravity of that endeavor.

Consider the period following the Enlightenment. This era involved a significant shift, deliberately turning political and intellectual focus away from what were often seen as intractable questions about humanity's destiny. Political thought largely detached itself from cosmology, concentrating instead on building stable nation-states, managing human-driven economies, and refining systems of governance. This framework, which prioritized short-term, pragmatic, human-scale concerns, led some thinkers like Hegel, and later Fukuyama, to suggest that history itself had effectively reached its destination in this modest utopia—the "End of History."

The development of transformative artificial intelligence, however, fundamentally challenges this settled perspective. We are now seriously contemplating the creation of entities whose intelligence and capabilities could vastly surpass our own. This prospect forces us to engage with foundational questions about the long-term trajectory of human civilization, our relationship with potentially superior non-human intelligence, and the possibility of needing to radically rethink our established economic and political systems. In their book The Age of AI, Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher capture the historical significance of the moment, describing it as a transition from an 'Age of Reason,' defined by human cognition and agency since the Enlightenment, towards an 'Age of AI,' demanding a new understanding of our place within the structures permitting our existence.

Our dominant intellectual traditions, shaped by the focus on manageable, human-centric problems, may lack the ready-made conceptual tools to adequately grasp the sheer scale and implications of this potential shift.

This conceptual inadequacy suggests the ontological translations explored earlier might hold value, despite their inherent risks. To grapple with futures potentially reshaped by AI, cautiously adapting existing concepts, even those laden with historical or religious weight, could prove useful. Employing such resonant language, while demanding careful justification and awareness of potential misuse, might better convey the truly paradigm-shifting nature of this potential transformation than purely technical or conventional political terms allow. By evoking deeper cultural frameworks, this compatibilist approach could foster a broader societal engagement with these profound challenges, enabling a richer dialogue commensurate with the stakes involved.

Religious traditions, after all, evolved over millennia to address concerns of ultimate meaning, world-altering transformation, and humanity’s relationship with powers vastly exceeding its own.

Perhaps, then, a dose of ontological shock is precisely what our complacent discourse requires. Maybe we would confront the implications of our creations more honestly if, instead of chanting 'feel the AGI,' the researchers building these systems shouted 'God is Great' as they piloted their breakthroughs straight into the towers of our civilization.

Imagine if Sam Altman had appeared before Congress and declared openly and earnestly that he was on a quest to build God. Perhaps then, senators would have grasped the situation more clearly. Perhaps then, the public discourse around AI would have shifted from mundane concerns about labor markets and national competitiveness to deeper existential questions about humanity's future and would have forced us to confront the enormity of the challenges ahead.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the challenge lies not merely in developing transformative AI, but in developing the conceptual, socio-cultural and linguistic frameworks adequate to its potential consequences. Transontological Compatibilism, as explored here, offers one potential strategy for navigating this complex terrain. It encourages us to look beyond surface incompatibilities and identify the functional roles concepts play across different worldviews, fostering translation rather than outright rejection. While the risks of invoking historically loaded terms, particularly those associated with religion, are undeniable and warrant great caution, the risks of failing to communicate the profound, potentially species-altering nature of the AI transition may be greater still. As we stand on the cusp of potentially introducing 'God-like' powers into the world, we may find that consciously and carefully adapting the language once used to speak of the divine is not an act of irrationality, but a necessary step towards collective sense-making and responsible navigation of the unprecedented era ahead. The task requires not just technical ingenuity, but philosophical flexibility and a willingness to bridge ontological divides in pursuit of shared understanding.