Welfare Estimation 102: Welfare is a Myth

By Richard Bruns @ 2022-02-10T16:44 (+22)

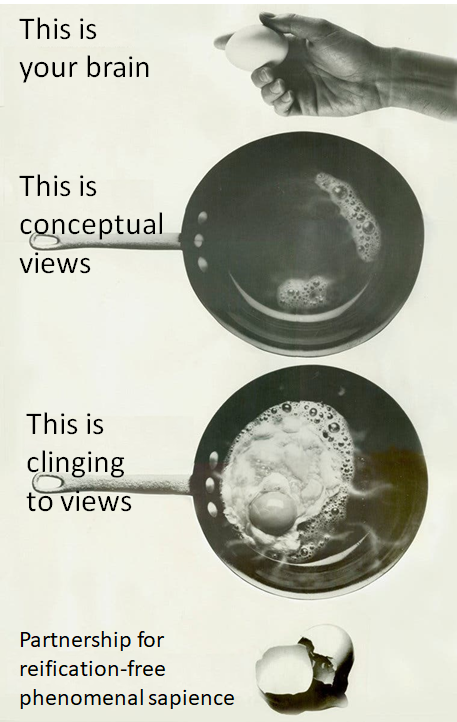

The main message of this post is that the concept of ‘Welfare’ (and everything adjacent to it in idea-space, like Utility and Happiness) is a fiction with basically no connection to physical reality. It is a pseudoscientific myth. Trying to measure Welfare as though it were a real physical thing like the electroweak force is impossible, wrong, and also not even wrong, all at the same time.

Nobody should attempt to do welfare estimation unless they grok this. The project of welfare estimation is not a scientific project, it is an engineering one. We are not discovering an objective fact about physical reality; we are making an artificial tool to serve one of our needs.

In essence, we are manufacturing a myth. This is a good thing, if done properly and responsibly. Myths are a valuable coordination mechanism, and I think that the myth of Welfare can probably help us coordinate our collective action better than any alternative we know about.

Reality vs Artificial Labels

What follows is a very brief description of what I mean by ‘Welfare is a fiction’. There is a vast philosophical literature around these topics that I cannot begin to do justice, but here is the essence:

Physical reality is subatomic wave-particles vibrating around in spacetime, whose behavior is fully explained by math. The subatomic things vibrating around in spacetime have an objective existence that is independent of any human observer. But your brain does not have access to that reality and it never will. Everything that you perceive, even the most ‘simple’ physical sensations or observations, is a signal generated by a very complicated system of sensory cells and neurons. This signal-processing system, and the world of perceptions and categories it generates, is both unique to you and heavily influenced by social conventions.

None of the labels that your brain attaches to things have any objective existence in the world of wave-particles. Your brain will try to convince you that your perceptions are real and fundamental things, but it is lying to you. All words and concepts do not have any fundamental existence at all, as far as the subatomic particles vibrating in space are concerned. Words and concepts are nothing more than a kludgey artificial protocol that primates use to communicate with each other. They are correlations, artificial simplifications of a vastly complex territory, and/or shared social conventions. And abstract ideas like ‘Welfare’ or ‘Utility’ are especially far from physical reality.

The mathematical tools of physical science or engineering are very useful for predicting the behavior of the wave-particles vibrating around in spacetime, and the simple aggregate materials made from them. But trying to apply these tools to the world of mental ideas and concepts, aka the outputs of a horribly complex neural network classifier, is a category error.

So why am I teaching you how to use math on a fake thing? Simple. Myths are a valuable coordination mechanism, and I think that the myth of Welfare can probably help us coordinate our collective action better than any alternative we know about. Consider the following parable:

The Parable of Athena-Virtue

Imagine that the polity and culture of ancient Athens survives into the modern day, with access to modern science and computers and analytical methods. Now imagine that all of the citizens and philosophers of Athens truly believe in the existence of the goddess Athena. There is near-universal agreement that the purpose of life was to worship Athena by exemplifying Her virtues, and that the government should encourage these virtues as much as possible.

In the past, people used rhetoric to argue about how much different proposed policies would exemplify the virtues of Athena. There were endless debates over things like whether a value-added tax or an income tax was more virtuous, or if it was virtuous to raise taxes to upgrade the sewer system. These debates were never resolved, and many people noticed that the government usually did whatever the most convincing debater, or the demagogue with the most popular support, happened to want.

Now, however, Athenians use math and science to decompose and measure all the components of Athenian virtue. Lay people and learned philosophers are asked an endless array of very specific questions, like “Will Athena smile more upon one who says a kind word to a stranger, or one who moves a rock out of the road that has a 12% chance of causing that person to hurt their toe?” In this way, the virtue-scholars assign numbers to all possible actions, both public and private. Entire libraries have been filled with scholars assigning Athena-virtue measurements to various actions.

For any proposed public policy, scholars devote a great deal of intellectual rigor to determining how much Athena would or would not approve of the action. They measure all of the effects of the policy, and use the virtue surveys to determine how to compare and add up those effects. Finally, they make pronouncements about how much Athena-virtue the policy will create.

For many outsiders, all of this ivory-tower activity is a source of amusement. Everyone outside Athens knows that the goddess Athena does not exist, and that even if She did, trying to measure Her virtues would be a fool’s errand. They know that all of the surveys are just a complicated way of asking people what they happen to like at that moment.

And yet, nobody can deny that Athens seems to be functioning a lot more smoothly now than it ever did before. Instead of arguing in circles, people conduct more virtue-surveys, or study their rival’s estimation code to look for bugs. Most Athenians, and even most outsiders, agree that the public policy of Athens is more sane and rational than it ever has been, with important things being taken care of and less-important things ignored.

It has gotten to the point that some outsiders are thinking of copying the methods of Athens. Even though Athena never existed and never will, the people’s belief in Athenian virtue, and their desire to have more of it, is a thing that can be measured. And aside from a few interesting cultural quirks, Athenians’ consensus belief in what maximizes Athena-virtue corresponds pretty well to what most people agree is a good life.

What is our goal?

The parable is painting a picture of a fictional utopia that runs well even though it is based on a delusional myth. It works because its myth is better than the competing myths, and its public policy is based, at least in part, on surveying people and then using that as a basis of cost-benefit analysis.

It seems to be a human universal that societies run on shared myths. Throughout history, most of these have been explicitly religious, but modern states run on a set of semi-religious national myths that use sacred symbols and meanings from history to encourage good behavior, motivate action, and form common knowledge about what should and should not be done in public policy. This probably isn’t going to change as long as society is mostly composed of baseline humans.

Even though these myths are completely fake at the level of physical reality, they are very real at the level of conceptual-social reality, and their reality is generated and sustained by the beliefs and actions of the people in a society. What the Athena-scholars have done is to democratize the foundational myth of their society. Instead of a story handed down by the elders and manipulated by demagogues, it is a voting-like process that everyone can participate in. By making the myth legible and accessible to everyone, it starts to work better for everyone.

My goal is to do something similar. I want ‘Welfare Maximization’ to be one of the sacraments of society’s civil religion. Not the only one, of course, because sacraments like ‘Liberty’ and ‘Natural Rights’ are doing a lot of good and valuable work. All of these things are fictional myths, and they are all very important, and they are based on things that most people instinctively believe or desire to be true. Welfare maximization should not override other sacred values, but it should be used when there are no sacred values involved, or when multiple sacred values are at odds with each other and you need a tiebreaker.

Practical Rituals of Consensus

Collective decision making is a hard problem. Much of human history is the story of a search for rules and systems that encourage people to do good things for each other and discourage them from doing bad things to each other. We’ve gotten a lot better at this in the last few hundred years, and one of the best social technologies of the past few hundred years has been voting in free and fair elections.

When it comes to voting, most people understand that they are engaged in a preference-aggregation ritual rather than a Search For Universal Truth. It is widely understood that no election result says anything fundamental about the universe, or ethics. It is just the people collectively operating under a set of predetermined rules to say how society will be governed for the next few years. Cost-benefit analysis and welfare estimation should be seen in exactly the same way.

I want to democratize welfare estimation by keeping it aggressively simple. A high-school class should, with proper training, be able to understand the process, and contribute to the societal supply of measurements that make it work. Figuring out how much value high-schoolers place on some aspect of life or policy should be very much like running a school election. Yes, there are some technical details you need to get right, but not too many. The baseline instructions for doing welfare estimation should be seen as something like Robert’s Rules of Order: a reasonable manual for collective action that every citizen should understand the basics of.

More specifically, in my utopia, high-school algebra is replaced by a ‘civil statistics’ class that teaches the basics of survey interpretation, probabilistic reasoning, and cost-benefit analysis. Algebra, especially as taught now, is useless for at least 90% of the population. Only a small percentage of people will ever need it, and those that do can be taught it in college. But a kind of math that shows how to connect voting and surveys to public policy can and should be used by everyone.

So, even though I know that welfare is fake, I'm going to be a stickler for detail and insist that the fake thing be measured in a regular and proper way, much like how we must do parliamentary procedure in a regular and proper way. And, in this case, I think there are a lot of good reasons for making the proper way correspond to the way that you would measure the thing if it was a real physical quantity. That math is a set of rules that work well, and that many people are familiar with.

Believe the myth a little, but not too much

The process of doing cost-benefit analysis won’t work if you are completely cynical. You have to do it rightly and honestly, and you have to believe that you are doing useful work in helping people choose reasonable actions and make good decisions. This usually means that some part of your brain should think that you are measuring something real and true, in the same sense that an election worker should believe in the impossible myth that ‘The Will Of The People’ is a real thing that can be honestly measured and should not be tampered with.

But don’t get dogmatic or fanatic about it. In particular, please don’t try to replace Jesus with Utility or Welfare. It won't work. If your attraction to utilitarianism comes from some sort of deep spiritual need to find something transcendent to organize your life around, you'll just disappoint yourself and you'll make trouble for everyone else.

For a kind of mathematical or systematic mind that is used to thinking in terms of axioms and proofs and absolute truth, this advice may seem like insanity. But it is not, and learning how to use rigorous systems of thought without letting them use you is an important life skill. For more about how to develop and operate in this fluid mode, I highly recommend taking a deep dive though David Chapman’s meaningness blog.