Moral Circle Expansionism (Effective Altruism Definitions Sequence)

By ozymandias @ 2025-07-28T17:47 (+21)

Normal people care about some groups of beings more than others. Sometimes people talk about this as “moral circles” or “circles of concern,” imagining something like this.

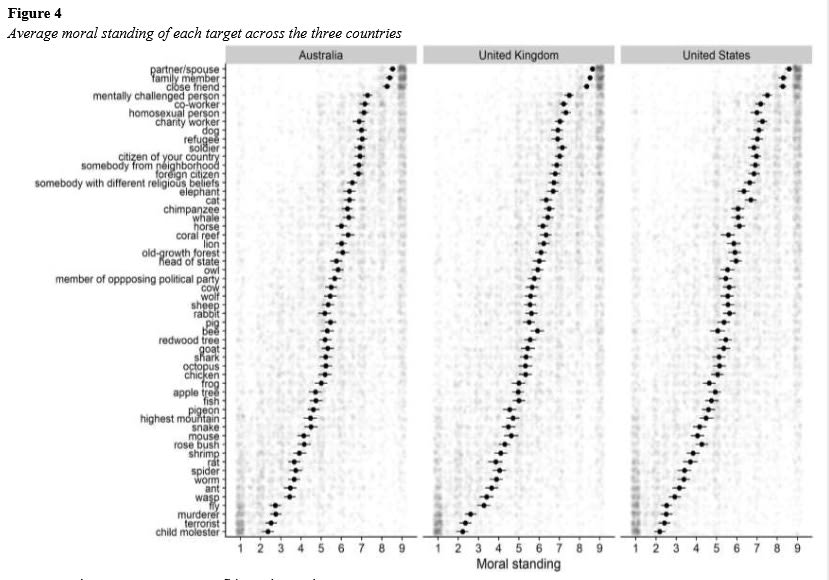

A 2021 study asked people to rate how obligated they felt to show moral concern for the welfare and interests of various targets. Here’s the chart:

There are some really funny results. (Look at “member of opposing political party”!) Overall, it seems like most people have moral circles that look something like this:[1]

- Innermost circle: spouse, family members, and close friends.

- Second circle: marginalized groups, people you know but not very well.

- Third circle: admirable people, random strangers from your country, dogs.

- Fourth circle: foreigners, wild animals, animals from other pet species, the environment, outgroup members.

- Fifth circle: animals from food species, predatory animals, trees, unusually tall mountains.

- Sixth circle: pest species, evil people.

If we take “ants” as the zero point, then the sixth circle is actually inverted.[2] People aren’t just indifferent to pest species, terrorists, and child molesters; they actively want members of those groups to suffer.

Effective altruists don’t do any of this. Effective altruists adopt what Peter Singer in Practical Ethics terms the “principle of equal consideration of interests”: we should care equally about the well-being[3] of everyone who is affected by our actions, regardless of race, gender, nationality, location, or species.

Now, as soon as I said that, I’m going to walk it back. As a human, you can’t actually adopt the principle of equal consideration of interests. You are obviously going to care more about yourself, your family, your friends, and your children than about random strangers. If you tried to follow the principle of equal consideration of interests, you would have a nervous breakdown.

What you can do—and what effective altruists do do—is collapse the six or so circles into three:

- Innermost circle: spouse, family members, and close friends.

- Second circle: people you know but not very well.

- Third circle: literally everyone else.

Collapsing the circles involves making four changes. I will talk about them in order of importance, starting with the least important.[4]

First, effective altruists tend not to care about marginalized people more than other people. Marginalized people usually suffer more than other people, and it is often cheaper to help them. So this has no effect in practice, to the point that I’m not actually sure whether my claim is true or just something I made up to make my theory more elegant. But I included this section to please those who want to dunk on Woke.

Second, effective altruists reject moral desert. I hesitate to make too much of this, because rejecting moral desert is (almost) completely irrelevant to effective altruist decision-making. But anthropologically it’s such a noticeable feature of effective altruist psychology that I have to bring it up.

Normal people have the sixth, inverted circle. Not only do they not care about child molesters’ well-being, they want child molesters to suffer. To be sure, normal people don’t have many people in their inverted circle: you’d have to be either unusually vindictive or unusually unlucky to run into someone in the inverted circle as often as once a week. But normal people still believe it is morally right for some people—terrorists and Nazis, sex offenders and people who torture dogs—to suffer.

Effective altruists disagree. To be sure, in many situations it produces the best outcomes for bad people to suffer. For example, punishing bad behavior can keep people from behaving badly in the future, and sometimes you need to lock people away where they can’t hurt anyone. But some effective altruist[5] once wrote that, if she had the option to give Hitler a nice dream— immediately before he died of suicide so it couldn’t strengthen him to commit more atrocities, and secretly so no one would be incentivized to commit the Holocaust—she would. Because she thinks it is good, all things equal, for Hitler to be happy.

I don’t have the inverted circle, and its existence is definitely the aspect of normal people’s psychology that makes me feel most like I’m surrounded by sadistic psychopaths.

Third, the matter of species. Like I said, effective altruists accept the principle of equal consideration of interests. If two beings have equally important interests, you ought to consider them equally, regardless of species. You can’t murder Chewbacca and then say “it was fine for me to kill him, because he’s not human, he’s a Wookie.”

Does that mean that we need to treat shrimps exactly the same way that we treat humans? Every shrimp farm is Treblinka? Every shrimp scampi makes you Ted Bundy?

I don’t think so. Humans aren’t that different from each other. Every human has about the same capacity for well-being as every other human.[6] But humans are very different from shrimps—or dogs, or chickens, or ants, or rosebushes, or bacteria.

It’s possible that shrimps don’t have the capacity for well-being at all.[7] Rosebushes and bacteria certainly don’t. If a being isn’t capable of experiencing well-being, clearly effective altruists wouldn’t care about it. Effective altruists disagree fervently about which beings have the capacity for well-being. I personally have met both an effective altruist who excludes chimpanzees and an effective altruist who is worried about bacteria, but both positions are very extreme. The most typical position seems to be straightforward inclusion of all vertebrates, healthy concern about at least some invertebrates, and gleeful trolling of normie vegans by telling them clams are meat plants. Delicious, delicious meat plants.[8]

Even if shrimps have the capacity for well-being, that doesn’t mean they matter as much as humans do. Shrimps have less capacity for well-being than humans do, or to put it in a different way, their interests are less important than a human’s. To steal a metaphor from Rethink Priorities, you can think of well-being as water, and some individuals as larger “buckets.”

I also stole their image, in case you have trouble visualizing a teeny-tiny bucket.

For more on this subject, I recommend reading Rethink Priorities’s excellent Moral Weights Project, which provides crude but useful estimates of the moral weight of various species.

Let’s look again at normal people’s circles of concern about animals:

The primary factor affecting how people rank a species seems to be its use to humans: dogs, then other pet species like cats and horses, then wild animals, then food species, then pest species. The second most important factor seems to be how “charismatic” the species is: majestic whales and lions and coral reefs are far ahead of wild animals which are scary (sharks) or simply unappealing (octopuses).

From any well-thought-out philosophical perspective—not just effective altruism—this prioritization scheme is nonsense. I have read numerous books about animal ethics and haven’t found a single author defending the claim that we should care more about cute animals than uncute animals. Even if you believe we have a special obligation to domesticated animals, you can’t defend having less of an obligation to pigs than to owls.

This system sure is convenient though. If you’re indifferent to the well-being of food species, you can eat meat without guilt. If you want pests to suffer, you can put out rat poison with satisfaction. And if you only care about elephants and lions, then mass extinction suddenly isn’t a big deal.

People talk about speciesism as treating humans differently from other animals. To be honest, I think most of the time speciesism is treating some animals differently from other animals: it’s not okay to torture dogs because they’re pets; it’s okay to torture pigs because they’re food. Some effective altruists don’t care about chimpanzees and some do care about bacteria, but no effective altruist makes arbitrary distinctions between species based on nothing but human convenience.

Fourth, effective altruists don’t care about some strangers more than other strangers.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle, a granfalloon is a false community, a sense of connection you feel based on ultimately meaningless category membership. Vonnegut gives examples: “the Communist party, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the General Electric Company, the International Order of Odd Fellows - and any nation, anytime, anywhere.”

Most of the divisions people make in their outer circles—neighborhood, religion, political party, nationality—are granfalloons. By all means, love your friends and family more than strangers. But (effective altruists say) don’t divide up strangers based on some arbitrary made-up kinship. If someone I’ve never met lives two thousand miles to the east of me, in Chicago, she’s my friend and sister. But if someone I’ve never met lives two thousand miles to the south of me, in Mexico City, she’s an outsider and my enemy. What? No. That’s stupid.

This is, I think, the sine qua non of effective altruism. If you held a gun to my head and made me reduce effective altruism down to four claims, the first would be: don’t care about some strangers more than other strangers because of arbitrary group membership.

If I actually know you, I’ll care more about you; that’s human and not doing so would be neither possible nor desirable. But if a stranger is dying in horrible pain, I care as much if they’re black as if they’re white—as much if they’re a Republican as if they’re a Democrat—as much if they’re in Africa as if they’re in America—as much if they’re half a world away as if they’re in front of me right now. That is the first part of what effective altruism is, the first thing that ties these three strange groups together.

- ^

This is the result of me peering at a chart and dividing up what is obviously a continuous spectrum into groups, so it’s kind of fake.

- ^

Which is hard to fit into a circles diagram.

- ^

Which, remember, doesn’t just refer to happiness or pleasure, but to anything that is good or bad for a specific being.

- ^

Readers may notice that I’ve excluded “cares about future people.” This is because I disagree with the usual effective altruist take that longtermism comes from caring about future people’s interests. I will discuss longtermism in a future post.

- ^

I apologize for the lack of credit, because I can’t find the original post.

- ^

Assuming you have a normal definition of well-being and not a weird pseudo-Nietzschean Greek statue avatar definition.

- ^

- ^

I’m allergic to clams so I can’t participate in the fun. :(

idea21 @ 2025-07-29T08:58 (+1)

I dare to introduce the concept of "functional morality" in the sense of the internalized moral principles that advance moral behavior on the part of the individuals who make up a society.

That is: if a person or group of people (an ideological movement... like EA) develops a moral conception that, while producing altruistic goods (charity, altruistic economics), serves to influence the whole of conventional (less ideologized) society toward more moral behavior, then this is the best moral behavior (also from a utilitarian point of view).

If we emphasize that it is normal to favor relatives and not those suffering in distant lands (like Africa), we are not practicing "functional morality." We must acknowledge our weaknesses, not simply accept our moral shortcomings.

If we talk about saving shrimp and farm chickens, we're not being "functional" either, as these are controversial issues that many well-intentioned people consider extravagant.

As an example cited by some authors, in the fight against slavery, anti-slavery activists were adept at pointing out that the slave trade was not only terrible for poor Africans, but also for the crews of slave ships. That was functional.

The most "functional" morality (and it seems to me also the one most appropriate to utilitarianism) is to promote active charity that is associated with a visualization of virtue on the part of altruistic agents. Altruism must be conceived as a lifestyle, not a mere quantificatiom of goods. Utilitarianism must be seen as a consequence of an altruistic lifestyle that turns "visible" to society as a whole. This lifestyle must guarantee altruistic action and be associated with a benevolent rationality that could be somewhat attractive (that provides, at the very least, emotional and affective rewards that are evident to conventional society).

I believe this is the way moral progress has been achieved so far, and it should continue to be so... in accordance with the circumstances of today's culture, which are not those of the past.

SummaryBot @ 2025-07-28T20:51 (+1)

Executive summary: This exploratory post defines "moral circle expansionism" as a core principle of effective altruism, contrasting it with common moral intuitions by advocating equal moral concern for all beings with the capacity for well-being—regardless of species, nationality, or moral desert—and exploring the psychological and philosophical shifts this entails.

Key points:

- Moral circles reflect how people prioritize concern, with most favoring close relations and actively disfavoring certain groups like pests or moral outcasts (e.g., child molesters), creating "inverted circles" where suffering is seen as deserved.

- Effective altruists aim to simplify these circles into just three—loved ones, acquaintances, and everyone else—guided by the principle of equal consideration of interests, though full impartiality is acknowledged as psychologically unrealistic.

- Four major shifts characterize this compression: rejecting extra concern for marginalized people as a default (though this may have little practical impact), rejecting moral desert (e.g., opposing gratuitous punishment even for Hitler), expanding moral concern across species lines, and ignoring arbitrary group membership (e.g., nationality).

- Species inclusion depends on capacity for well-being, not usefulness or charisma; effective altruists may disagree on which beings qualify, but they reject speciesist distinctions rooted in human convenience (e.g., caring more about dogs than pigs).

- The metaphor of “well-being buckets” helps illustrate that not all beings’ interests are equally weighty—some creatures (like humans) may matter more due to greater capacity for well-being, but that doesn’t justify ignoring others entirely.

- The sine qua non of effective altruism, according to the author, is not discriminating among strangers based on arbitrary categories like nation or race—a universalist stance underpinning moral circle expansionism.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.