Only Aggregationists Respect the Separateness of Persons

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-08-15T15:25 (+12)

This is a linkpost to https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/only-aggregationists-respect-the

Separate people have independent value

I often find myself thinking that the conventional wisdom in moral philosophy gets a lot of things backwards. For example, I’ve previously discussed how deontology is much more deeply self-effacing (making objectively right actions, and not just bungled attempts to act rightly, lamentable) than consequentialism. In this post, I’ll explain why I think that only “aggregationist” views—on which five people being tortured to death is five times worse (all else equal) than just one person suffering this awful fate—fully respect the separateness of persons.

Ethics as Normative Psychology

First, some background. Normative ethics can be understood as specifying what psychological attitudes are warranted towards different objects. To say that life is good is to say that it warrants desire or similar pro-attitudes (in an idealized sense that abstracts away from our cognitive limitations).

So to say that each person’s well-being is a separate, non-fungible good, is to say that we should (ideally) have distinct non-instrumental desires for each person’s well-being. (This is the core idea of my ‘Value Receptacles’ paper.)

You could imagine a kind of utilitarian who fails to do this: someone who just has a single desire to maximize aggregate welfare, and sees each person as a constitutive means to this end, just as individual dollar bills are mere constitutive means to your aggregate wealth (you don’t care about the bills as individuals—they are replaceable without regret). Then, rather than feeling torn when forced to choose between two equally worthy lives, this agent would feel stark indifference: the choice of which life to save would seem no more significant to them than the choice between a $20 bill or two tens. I think it would be obscene to view human lives as fungible in this way, so I show how to understand utilitarianism in a way that avoids this flaw (but still allows you to make trade-offs—you can retain commensurability without fungibility). By having separate desires for each person’s well-being, my token-pluralistic utilitarian values each person separately in the most literal sense, and this is reflected psychologically in their (i) feeling the loss whenever an individual is harmed, and (ii) feeling a different loss (due to a different desire of theirs being thwarted) depending on which individual is harmed.

In what follows, I’ll argue that anti-aggregationists fail to value people independently in this way.

Belief-Desire Psychology and Independent Desires

Two of the most important kinds of mental states (as inputs to rational choice and action) are beliefs and desires. Beliefs aim at truth, representing how we take the world to be. Desires aim at the good (or desirable), representing how we want the world to be. Epistemology addresses questions about what we ought to believe; ethics is (most fundamentally) about what we ought to want.

Some of our desires are not entirely independent of each other. I may want some chocolate; I may want some fudge; but if one of these desires is satisfied, I may cease to want the other treat. (Maybe what I really wanted is just “something sufficiently tasty”, and the fudge and chocolate are at least partly-fungible means to this common end.)

Or I may also want to go for a nice walk in the woods, but not after eating a large meal. In this case, there’s no substitution effect; it’s more of a conflict. The walk wouldn’t be “nice” if I was feeling overgorged at the time. But that’s a purely instrumental form of interaction; really the two desires maintain a deeper sort of independence, or so I’m inclined to think.

Here’s a possible test: suppose I could separate out the two events to minimize causal interactions and keep “all else equal”, as is best practice for thought experiments. Would enjoying a walk one day do anything to undermine the desirability of enjoying a chocolatey desert the next day (or vice versa)? Presumably not. We could imagine some strange person for whom the two acted as substitutes, but if I really value both separately and independently (as I take myself to do), then I’ll much prefer the prospect of satisfying both desires (over time) rather than just one of them.

This may all seem truistic. Of course we prefer to satisfy more of our desires rather than fewer. That’s just what it is to want all the things rather than just, say, a disjunction of them—like fudge or chocolate. In effect, what we’re observing here is that independent desires aggregate. If you have “two desires” that don’t aggregate in this way, that would seem to indicate that they aren’t actually independent, fundamental desires. Maybe they’re just two fungible means to satisfying one deeper desire. (Remember this in what follows. It’s key to understanding what’s perverse about moral anti-aggregationism.)

Anti-Aggregationists Don’t Separately Desire Each Person’s Well-being

So here’s something I find deeply appalling about anti-aggregationists: They don’t want all the morally good things! For example, after offering a kind of contractualist justification of aggregation,[1] Flo writes:

Still, the reason you should help more instead of fewer is not because there’s a bunch of “intrinsic value” in the world that globs together to form an even bigger intrinsic value that you’re supposed to care about even more. Good is still good-for, and goodness of states of affairs is just an approximate way of talking about our obligations. This is why I don’t feel like the emotional appeals utilitarians on here use against non-consequentialism are very forceful. “You would save the five over David, but you wouldn’t steal the drug from him to save the five? You care about some magical metaphysical relation between a person and their ‘property’ more than people’s lives?” No, the case gives no evidence as to how much I value people’s lives; an innocent individual dies in either case. Nobody is having a five-times-worse outcome inflicted upon them by my choice not to steal. I do care about property rights more than I care about imaginary aggregations of goodness, though.

This is a lovely summary of what I take to be a common perspective among non-consequentialists. I expect plenty of moral philosophers would sign on to this statement. So I don’t mean to be picking on Flo in particular when I say: this whole framing of the dispute is hopelessly confused.

Good depends on good-for, as welfarists claim. But if you refuse to move from claims about “good for” to “good” (or desirable) simpliciter, you are implicitly refusing to care about more than one person at once, or to recognize that multiple people matter independently. (This is the presupposition behind taking it to be relevant that “Nobody is having a five-times-worse outcome inflicted upon them.” Why else would anyone think that all the badness had to be contained within one life in order for it to matter? You cannot recognize the full horror of the Holocaust by only looking at a single victim in isolation. Every other victim matters in addition. To deny this would be stark moral insanity.)

Of course, nobody should care fundamentally about “big globs of intrinsic value” or “imaginary aggregations of goodness”. What you should care about is concrete people (plural), and you should care about each person separately and independently. What that means—in consequence of having multiple genuinely independent desires—is that a rational agent with the prescribed desires will want more people to be saved rather than fewer. (Notice that an agent with this plurality of desires receives five times as much desire-satisfaction in the event that five lives are saved rather than just one.)[2] People aren’t like fudge and chocolate, where any one will suffice. Each person matters independently of the others.

What does the anti-aggregationist agent desire, by comparison? We’re told that whether one person dies or five, “an innocent individual dies in either case.” It sounds like the desire(s) corresponding to this view must be much more generic and binary. Whereas I think an ideal agent would care about each person separately, the anti-aggregationist agent (suggested by the quoted passage) appears to treat fixed-level harmful outcomes for different people—and even different numbers of people, each experiencing the full fixed level of harm—as entirely fungible. So long as no individual is “having a five-times-worse outcome inflicted upon them,” adding another victim doesn’t register as a morally significant difference. This seems… less than ideal!

The anti-aggregationist basically has their moral concern exhausted by a single generic desire that the worst-off position be less awful. We should, of course, all wish better for the worst-off individual. But if that is your only moral desire then you are failing to care about every other person in the world.

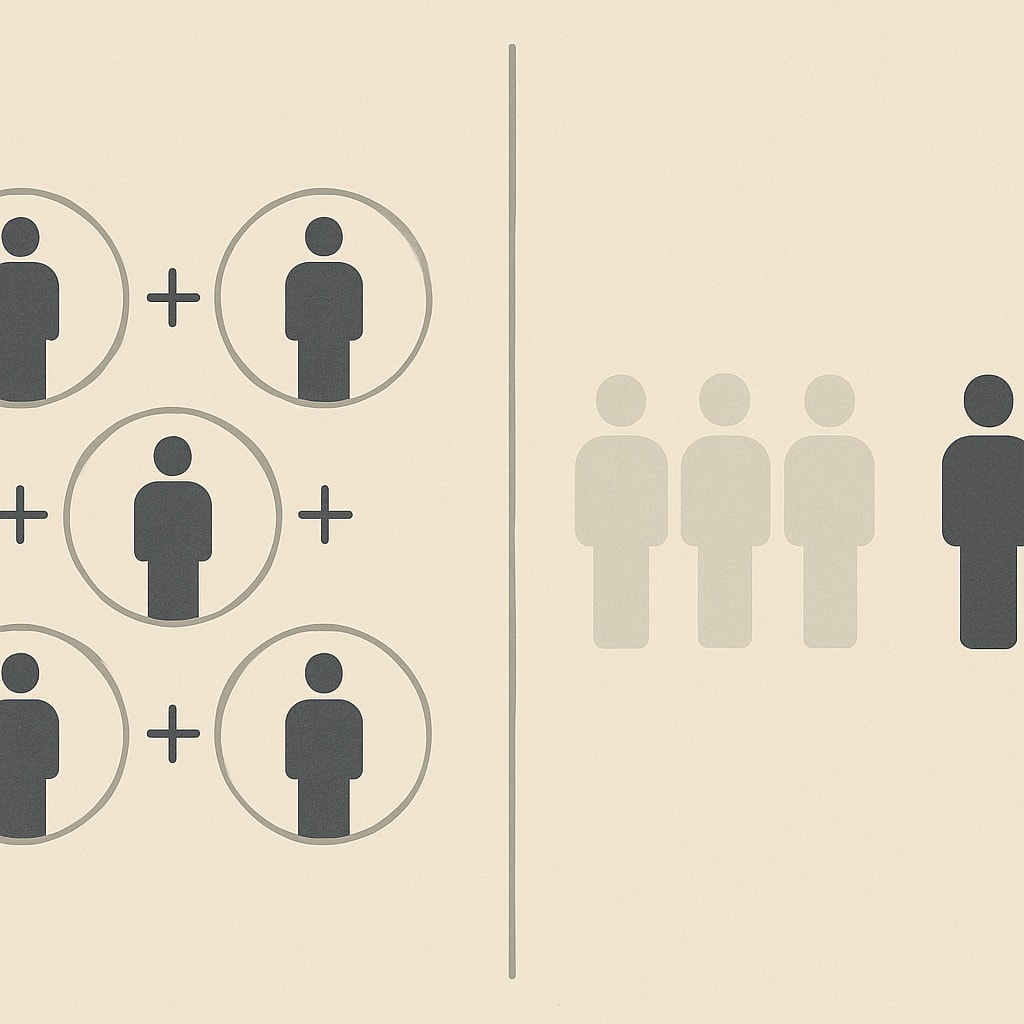

To make the contrast more concrete, consider who is more morally ideal:

Aggregating Amy: separately desires each person’s flourishing.

Generic Jim: literally only wants one thing and it’s fucking disgusting maximin.[3]

Now, I cannot understand how anyone could seriously claim that Generic Jim is more virtuous than Amy (let alone how they could claim to thereby be respecting the separateness of persons better than a utilitarian who holds up Amy as their moral ideal). Jim stops caring about someone’s suffering the moment he finds someone else who is worse off! He fails to treat each person’s suffering as mattering in its own right—maintaining its full force and independent moral significance no matter what is going on with other people. All that matters to him is that someone is suffering a fixed-level harm; it doesn’t even matter how many people suffer so.

This anti-aggregationist pattern of concern involves caring about a single de dicto role (“the worst off”) rather than caring about each and every concrete person. Amy wants each person to flourish rather than suffer, and her (equally-weighted) desires aggregate in such a way that she—like any decent person—is more bothered the more people who suffer and die. Conversely, the more people get to flourish, the more the world is to her liking. She doesn’t only look at one person and let their well-being settle her overall attitude towards the state of affairs. To truly care about everyone, you have to let everyone play a (sufficiently significant) role in your cognitive economy, shaping your overall verdictive attitudes. Only aggregationists do this.[4]

What is going on in moral philosophy?

When you look at it this way, it seems wild that anti-aggregationists managed to turn caring about fewer people into a putative virtue. I think the problem is that moral philosophers don’t think enough in telic terms, about what desires or preferences their moral theory “corresponds to” or renders objectively fitting.

Deontologists may implicitly be starting from a picture on which the moral agent has primarily self-interested concerns, along with a compensating—perhaps even overriding—desire to act rightly (or at least to avoid acting wrongly). Given this background picture, it’s natural to see the moral theorist’s job as being to spell out what considerations make acts right or wrong, which can then hook up to this explicit deontic concern in the moral agent. It’s all very abstract, which can easily lead one into absurdity (as I think has happened with anti-aggregationism being wholly motivated by philosophical confusions). But the thing I find most striking is how this methodology starts from assuming a kind of vicious lack of concern for others, which then needs to be “corrected” by means of explicit deontic moralizing.

This is not my conception of ethics at all. We do eventually need to offer guidance to imperfectly virtuous people, of course. I’m on board with that. But ethics needn’t start there, as I don’t think the ideal agent would engage in explicit moralizing at all. Rather, they would (as Aristotle suggested) simply want to do the right thing, for the right reasons. So I think it’s illuminating to start our theorizing by thinking about what that virtuous ideal would look like.

Once we attend to this question, it just seems undeniable that the benevolent utilitarian saint (Amy) is a much better person than the anti-aggregationist Jim (with his generic desire for the pattern of the world to satisfy maximin, and no independent desires for everyone else’s flourishing). I’m especially struck by the sheer moral stinginess of Jim’s generic and limited concern, in contrast to the overflowing abundance of good will that Amy directs towards every single one of us, a concern for our well-being that she maintains no matter who else is in the situation or what is going on with them. In maintaining an independent desire for our flourishing, Amy respects our separate value in a way that Jim does not.

I’m really curious whether, after reflecting on the psychologies of these two hypothetical agents, any anti-aggregationists out there really want to say that Jim is more virtuous after all, and if so how they would make that sound remotely plausible.

Coda: On the significance of “separate persons” talk

I can predict that many deontologists reading this post will react with the thought: “That’s not what we mean when we talk about the separateness of persons!” But let’s pause to think about what is worth talking about in this vicinity. Here are various candidate thoughts that different philosophers might (with varying degrees of warrant) take to be “pre-theoretic truisms” that an adequate moral theory should satisfy:

(1) A large harm or benefit to one cannot be outweighed by any number of smaller harms or benefits to many.

(2) Inter-personal trade-offs are harder to justify than intra-personal ones.

(3) Individual persons are morally “separate” in the sense that they should be valued in themselves and independently of each other (rather than, for example, having moral agents regard individuals as fungible—replaceable without regret—in the way that dollar bills are).

Of these three claims, I think only (3) truly deserves to be considered a “truism” that it would be embarrassing for a theory to violate. (1) and (2) are, I think, false.[5] Even if you think they’re true, there’s no obvious reason why a consequentialist should feel any pressure to share your verdict. So those principles seem like a poor basis for “objecting” to consequentialism. (3), by contrast, seems like the kind of principle that a decent theory needs to accommodate. “Your theory doesn’t respect the independent value of individual persons” is clearly a criticism, marking a theory out as not just yielding incorrect extensional verdicts about cases, but as deeply disrespectful in a way that is plausibly disqualifying.

I also think that, of the three options, (3) is clearly the closest match to the plain literal meaning of “respecting the separateness of persons”, so anyone using the latter phrase to instead stipulatively mean (1) or (2) is being gratuitously confusing. Worse, I think they’re rhetorically exploiting the ordinary meaning—associated with (3)—as a kind of “motte and bailey”, retreating to the stipulative definitions once it’s explained how utilitarianism doesn’t actually violate the separateness of persons in sense (3).

So, even if most moral philosophers have now come to use the term to mean (1) or (2), I think they should reconsider their usage. It is both more accurate and more philosophically significant to say that—in virtue of meaning (3)—value-denying anti-aggregationists fail to respect the separateness of persons. Contrary to the conventional wisdom in moral philosophy, the separate value of distinct persons is best respected by utilitarians and others who recognize—and aggregate—the value of each and every individual, while nonetheless holding the value of the individuals to be more fundamental than that of their aggregate. (We care about maximizing aggregate value because we care about all the individuals we thereby benefit, not vice versa.)

- ^

It’s a good argument (and could even be taken further)! But still not sufficient for true virtue, sorry.

- ^

Don’t confuse this observation with the tautological egoist’s attribution that the agent “only cares about” their own desire-satisfaction. The agent’s concerns are given by the contents of their fundamental desires, which here concern the well-being of other people. Good stuff, nothing selfish about it.

- ^

Maximin = making the worst-off position as well-off as possible.

- ^

Scanlon’s argument for numbers as tie-breakers hints in this direction—he notes it would seem disrespectful to a second person you could save if you didn’t treat their life or death as giving you any more reason to save the group than you would have had from the first person in the group alone. What I’m now suggesting is that this doesn’t go far enough. If you say that the importance of saving the second person is reduced at all by the presence of the first person, you have failed to value the two people separately and independently.

- ^

I don’t even think it’s “bullet-biting” to say so. I think (1) is obviously false, and (2) just doesn’t seem intuitively obvious either way—it seems like the kind of thing we should determine by doing some moral theorizing and seeing what we find. As it happens, I think inter-personal cases are significantly different, in that they have more reasons going in both directions (balancing out to make the tradeoff neither harder nor easier to justify, but creating a sense of “higher stakes” with greater angst).

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-15T15:41 (+2)

Executive summary: The author argues that only aggregationist moral theories—those that sum the value of each person’s well-being—truly respect the separateness of persons, because they require caring about each individual’s welfare independently, whereas anti-aggregationist views implicitly treat additional people’s suffering as morally irrelevant once a worst-off individual is identified.

Key points:

- Independent value requires independent desires: To genuinely value separate persons, one must have distinct, non-fungible desires for each person’s well-being; this leads naturally to aggregation, since satisfying more such desires is better.

- Anti-aggregationist psychology is morally stingy: By focusing only on the worst-off individual (e.g., via maximin), anti-aggregationists neglect the independent moral significance of others’ suffering or flourishing.

- Illustrative contrast: “Aggregating Amy” cares equally and separately about each person’s flourishing, whereas “Generic Jim” stops caring about others once someone worse-off is found—making Amy the more virtuous moral ideal.

- Misuse of ‘separateness of persons’: Philosophers often use the phrase to defend principles like “large harms to one outweigh many small harms” or “interpersonal trade-offs are harder,” but the author claims the more important and literal sense is valuing each person independently.

- Utilitarianism accommodates true separateness: Properly framed, utilitarianism values individuals first and the aggregate second—caring about the total only because each person’s welfare counts in its own right.

- Conventional wisdom reversal: Contrary to common deontological critiques, it is anti-aggregationists—not aggregationists—who fail to respect the separate value of distinct persons.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.