Disability Weights

By Jeff Kaufman 🔸 @ 2014-09-11T21:34 (+12)

If you're talking to two people, one with a small cut and another with multiple sclerosis, everyone present will agree that having multiple sclerosis is much worse. If you offered the two of them some magic option that would restore exactly one of them to full health, they would probably be able to agree on who should get it. But in general, how should we compare across people to figure out whose situation is worse, who would benefit more from treatment and who, everything else being equal, should be treated first? This example was easy because the difference was nice and large, but what do we do in harder cases?

One is to ask people questions like "if there were a surgery that could restore you to full health (without improving your lifespan) but had a 20% chance of killing you, would you take it?" If they say "yes" then this indicates that this disability, for this person, is more than 20% as bad as being dead. Ask these "standard gamble" questions to a lot of people with a lot of disabilities, varying the percentages, and you could build up a list of how bad different ones are, all on a common scale.

This would useful for balancing projects against each other, figuring out what to focus on, and generally setting funding priorities. Unfortunately people are really bad at answering questions like this. Mostly we're just bad at thinking about percentages and chances of bad things happening, but you also wonder about the problems of asking someone with, say, "Schizophrenia: acute state" to answer this sort of question.

You could fix this by asking people about "time tradeoffs". For example, you could ask someone with a disability about whether they would take a medicine that would restore them to full health for a year even if it took two years off their life. Alternatively you can ask people, generally public health professionals, if given the choice between curing 1000 people with disability X and 2000 people with disability Y which one they would choose. These "person tradeoffs" get us out of needing to ask about probabilities, which means we can probably trust the numbers more, but we're stuck either with collecting data from people with the disabilities in question (hard work, maybe the disability affects mental function) or trusting that public health experts fully understand what it's like to have different disabilities (seems unlikely). And even if we did decide that we were only going to collect data from people actually affected by a disability, remember that in many cases they can't actually give the comparison we want because they haven't experienced both having and not having the disability (ex: blindness from birth).

The first Global Burden of Disease Report (pdf) attempted to collect these weights for a large number of different diseases. They got a panel of public health experts to come to Geneva and through discussion around "person tradeoffs" came to consensus first on weights for 22 "indicator diseases". Then they agreed on weights for the several hundred remaining diseases by comparing them to these anchor conditions.

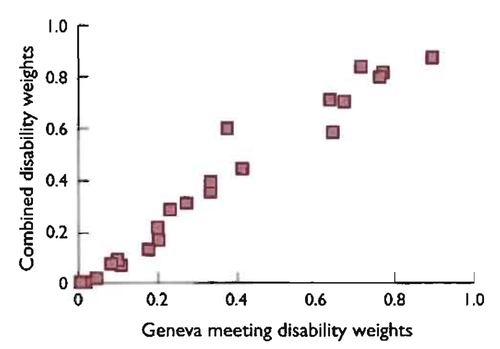

You might worry that the final weights would be really strongly affected by the particular consensus the Geneva group happened to get for the 22 anchors, but they ran nine other attempts with different experts and the average of those attempts correlates pretty well with the Geneva results:

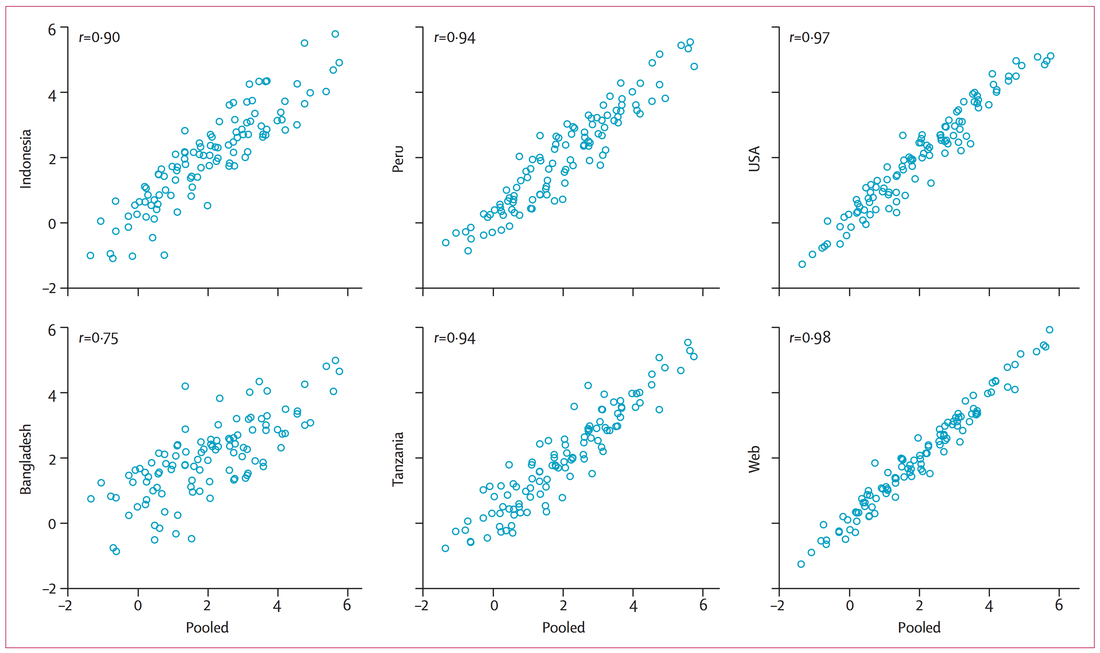

For the 2010 update to the Global Burden of Disease weights (pdf, also see the appendix pdf) they decided to take an entirely different approach. Instead of asking experts to figure out tradeoffs they asked lots of people in several countries (Indonesia, Peru, USA, Bangladesh, Tanzania, plus a 'global' internet survey) to do lots of comparisons where given two people they would say which one was healthier. This makes a lot of sense, asking lots of regular people, and the question is much simpler to answer. On the other hand, while I'm not sure experts are all that good at estimating how bad it is to have various disabilities I would expect regular people to be even worse at it. Still, there was at least pretty good correlation between countries:

But hold on: how did they turn a large number of responses where people said one disability was more or less healthy than another into weightings on a 0-1 scale where 0 is full health and 1 is death? It turns out that a quarter (n=4000) of the people who took the survey on the internet were also asked the "person tradeoff" style questions used in the 1990 version, which they called "population health equivalence questions". So they first determined an ordering from most to least healthy using their large quantity of comparison data, and then used the tradeoff data to map this ordering onto the "0=healthy 1=death" line.

This means that when we look at the cross-country correlations above we're only seeing their agreement on the relative ordering of conditions, not on the absolute differences. If people in Indonesia on average think that the worst disabilities are only 10% as bad as being dead while people in Peru think they're 90% as bad, this wouldn't keep them from having perfect correlation on a chart like this. Which is kind of a problem, because we need more than an ordering for prioritization.

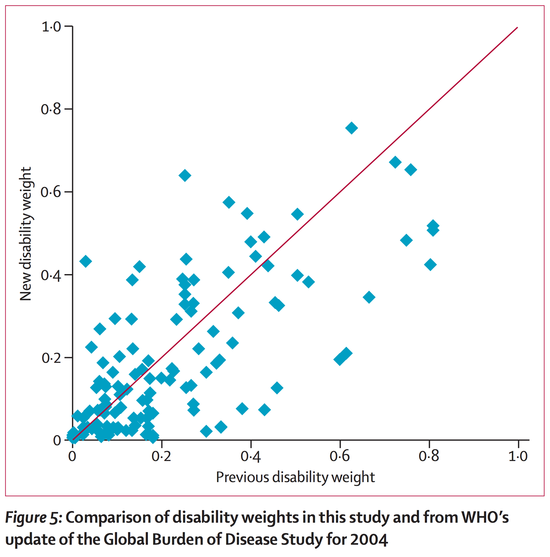

It turns out that this method of estimation actually gives pretty different results from the one used in the earlier version: [1]

Yes, there's a correlation, but it's pretty weak. And it's probably not just about the fifteen years between when most of the first estimates were made and when most of the second were; these aren't disabilities that are quickly changing. This indicates that what we're trying to measure is just not that well captured by the measurements we're making.

So, a summary. Getting good answers means asking people questions they're not good at thinking about, or that they are good at thinking about but don't have the right experience to be able to answer. It's not too surprising, then, that the answers you get via different methods don't agree very well. We do still need a rough way to say "benefit X to N people is better/worse than benefit Y to M people", but trying to do this in the general case doesn't seem to have worked out very well.

These disability weights are only one step in estimating $/DALY for various interventions, and the messiness here is in some ways much less than the messiness in the other steps. After reading about how these estimates came to be, I'm pretty glad GiveWell doesn't put much trust in them in figuring out which charities to recommend:

The resources that have already been invested in these cost-effectiveness estimates are significant. Yet in our view, the estimates are still far too simplified, sensitive, and esoteric to be relied upon. If such a high level of financial and (especially) human-capital investment leaves us this far from having reliable estimates, it may be time to rethink the goal.All that said—if this sort of analysis were the only way to figure out how to allocate resources for maximal impact, we'd be advocating for more investment in cost-effectiveness analysis and we'd be determined to "get it right". But in our view, there are other ways of maximizing cost-effectiveness that can work better in this domain—in particular, making limited use of cost-effectiveness estimates while focusing on finding high-quality evidence.

This isn't to say we should never use disability weights; even if they were just made up by one guy on the spot (and they're better than that) this would probably still be better in some cases than refusing to make quantitative comparisons at all. Getting rough numbers like this is especially useful for avoiding scope insensitivity problems, where you might be comparing a large number of people with something minor against a small number with something major.

(I'd really like to look into the QALY numbers people use and how they get them. I believe the process is similar, but I'm not too sure.)

For curiosity, however, and with all that in mind, what are the actual numbers they found? Here are the 2010 weights:

| 0.756 | Schizophrenia: acute state |

| 0.707 | Multiple sclerosis: severe |

| 0.673 | Spinal cord lesion at neck: untreated |

| 0.657 | Epilepsy: severe |

| 0.655 | Major depressive disorder: severe episode |

| 0.641 | Heroin and other opioid dependence |

| 0.625 | Traumatic brain injury: long-term consequences, severe, with or without treatment |

| 0.606 | Musculoskeletal problems: generalised, severe |

| 0.576 | Schizophrenia: residual state |

| 0.573 | End-stage renal disease: on dialysis |

| 0.567 | Stroke: long-term consequences, severe plus cognition problems |

| 0.562 | Disfigurement: level 3, with itch or pain |

| 0.549 | Parkinson's disease: severe |

| 0.549 | Alcohol use disorder: severe |

| 0.547 | AIDS: not receiving antiretroviral treatment |

| 0.539 | Stroke: long-term consequences, severe |

| 0.523 | Anxiety disorders: severe |

| 0.519 | Terminal phase: without medication (for cancers, end-stage kidney or liver disease) |

| 0.508 | Terminal phase: with medication (for cancers, end-stage kidney or liver disease) |

| 0.494 | Amputation of both legs: long term, without treatment |

| 0.492 | Rectovaginal fistula |

| 0.480 | Bipolar disorder: manic episode |

| 0.484 | Cancer: metastatic |

| 0.440 | Spinal cord lesion below neck: untreated |

| 0.445 | Multiple sclerosis: moderate |

| 0.438 | Dementia: severe |

| 0.438 | Burns of >=20% total surface area or >=10% total surface area if head or neck, or hands or wrist involved: long term, without treatment |

| 0.433 | Headache: migraine |

| 0.420 | Epilepsy: untreated |

| 0.425 | Motor plus cognitive impairments: severe |

| 0.422 | Acute myocardial infarction: days 1-2 |

| 0.406 | Major depressive disorder: moderate episode |

| 0.390 | Fracture of pelvis: short term |

| 0.399 | Tuberculosis: with HIV infection |

| 0.398 | Disfigurement: level 3 |

| 0.388 | Fracture of neck of femur: long term, without treatment |

| 0.388 | Alcohol use disorder: moderate |

| 0.383 | COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases: severe |

| 0.377 | Motor impairment: severe |

| 0.376 | Cocaine dependence |

| 0.374 | Low back pain: chronic, with leg pain |

| 0.373 | Lower airway burns: with or without treatment |

| 0.369 | Spinal cord lesion at neck: treated |

| 0.366 | Low back pain: chronic, without leg pain |

| 0.359 | Amputation of both arms: long term, without treatment |

| 0.353 | Amphetamine dependence |

| 0.352 | Severe chest injury: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.346 | Dementia: moderate |

| 0.338 | Vesicovaginal fistula |

| 0.333 | Burns of >=20% total surface area: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.331 | Tuberculosis: without HIV infection |

| 0.329 | Cannabis dependence |

| 0.326 | Abdominopelvic problem: severe |

| 0.323 | Gastric bleeding |

| 0.322 | Low back pain: acute, with leg pain |

| 0.319 | Epilepsy: treated, with recent seizures |

| 0.312 | Stroke: long-term consequences, moderate plus cognition problems |

| 0.308 | Fracture of neck of femur: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.200 | Iodine-deficiency goitre |

| 0.294 | Cancer: diagnosis and primary therapy |

| 0.293 | Gout: acute |

| 0.292 | Musculoskeletal problems: generalised, moderate |

| 0.288 | Drowning and non-fatal submersion: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.286 | Neck pain: chronic, severe |

| 0.281 | Diarrhoea: severe |

| 0.269 | Low back pain: acute, without leg pain |

| 0.263 | Parkinson's disease: moderate |

| 0.259 | Autism |

| 0.259 | Alcohol use disorder: mild |

| 0.254 | Infectious disease: post-acute consequences (fatigue, emotional lability, insomnia) |

| 0.236 | Conduct disorder |

| 0.235 | Severe traumatic brain injury: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.225 | Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis |

| 0.224 | Traumatic brain injury: long-term consequences, moderate, with or without treatment |

| 0.223 | Bulimia nervosa |

| 0.223 | Anorexia nervosa |

| 0.221 | Neck pain: acute, severe |

| 0.221 | Motor plus cognitive impairments: moderate |

| 0.221 | HIV: symptomatic, pre-AIDS |

| 0.210 | Infectious disease: acute episode, severe |

| 0.202 | Diarrhoea: moderate |

| 0.198 | Multiple sclerosis: mild |

| 0.195 | Distance vision blindness |

| 0.194 | Fracture of pelvis: long term |

| 0.194 | Decompensated cirrhosis of the liver |

| 0.192 | Fracture other than neck of femur: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.192 | COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases: moderate |

| 0.191 | Distance vision: severe impairment |

| 0.187 | Disfigurement: level 2, with itch or pain |

| 0.186 | Heart failure: severe |

| 0.177 | Fetal alcohol syndrome: severe |

| 0.173 | Fracture of face bone: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.171 | Poisoning: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.171 | Musculoskeletal problems: legs, severe |

| 0.167 | Angina pectoris: severe |

| 0.164 | Anaemia: severe |

| 0.164 | Amputation of one leg: long term, without treatment |

| 0.150 | Fracture of sternum or fracture of one or two ribs: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.159 | Major depressive disorder: mild episode |

| 0.157 | Intellectual disability: profound |

| 0.149 | Anxiety disorders: moderate |

| 0.145 | Crush injury: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.145 | Cardiac conduction disorders and cardiac dysrhythmias |

| 0.142 | Urinary incontinence |

| 0.130 | Amputation of one arm: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.136 | Injured nerves: long term |

| 0.132 | Fracture of vertebral column: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.132 | Asthma: uncontrolled |

| 0.129 | Dislocation of knee: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.127 | Severe wasting |

| 0.127 | Burns of >=20% total surface area or >=10% total surface area if head or neck, or hands or wrist involved: long term, with treatment |

| 0.126 | Intellectual disability: severe |

| 0.123 | Abdominopelvic problem: moderate |

| 0.110 | Lymphatic filariasis: symptomatic |

| 0.110 | Asperger's syndrome |

| 0.114 | Musculoskeletal problems: arms, moderate |

| 0.106 | Traumatic brain injury: long-term consequences, minor, with or without treatment |

| 0.105 | Chronic kidney disease (stageIV) |

| 0.101 | Neck pain: chronic, mild |

| 0.099 | Diabetic neuropathy |

| 0.097 | Epididymo-orchitis |

| 0.096 | Burns of <20% total surface area without lower airway burns: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.092 | Hearing loss: complete, with ringing |

| 0.080 | Intellectual disability: moderate |

| 0.080 | Dislocation of shoulder: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.088 | Hearing loss: profound, with ringing |

| 0.087 | Fracture of patella, tibia or fibula, or ankle: short term,with or without treatment |

| 0.086 | Stoma |

| 0.082 | Dementia: mild |

| 0.070 | Heart failure: moderate |

| 0.070 | Fracture of patella, tibia or fibula, or ankle: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.070 | Benign prostatic hypertrophy: symptomatic |

| 0.079 | Musculoskeletal problems: legs, moderate |

| 0.079 | Injury to eyes: short term |

| 0.076 | Stroke: long-term consequences, moderate |

| 0.076 | Motor impairment: moderate |

| 0.073 | Fracture of skull: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.072 | Severe toothloss |

| 0.072 | Fracture of neck of femur: long term, with treatment |

| 0.072 | Epilepsy: treated, seizure free |

| 0.072 | Disfigurement: level 2 |

| 0.066 | Angina pectoris: moderate |

| 0.065 | Injured nerves: short term |

| 0.065 | Hearing loss: severe, with ringing |

| 0.065 | Fracture of radius or ulna: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.061 | Herpes zoster |

| 0.061 | Diarrhoea: mild |

| 0.050 | Fracture of radius or ulna: long term, without treatment |

| 0.058 | Hearing loss: moderate, with ringing |

| 0.058 | Anaemia: moderate |

| 0.057 | Fetal alcohol syndrome: moderate |

| 0.056 | Severe chest injury: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.056 | Acute myocardial infarction: days 3-28 |

| 0.055 | Kwashiorkor |

| 0.054 | Speech problems |

| 0.054 | Motor plus cognitive impairments: mild |

| 0.054 | Generic uncomplicated disease: anxiety about diagnosis |

| 0.053 | Infectious disease: acute episode, moderate |

| 0.053 | HIV/AIDS: receiving antiretroviral treatment |

| 0.053 | Fracture other than neck of femur: long term, without treatment |

| 0.053 | Fracture of clavicle, scapula, or humerus: short or long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.051 | Amputation of both legs: long term, with treatment |

| 0.040 | Neck pain: acute, mild |

| 0.040 | Headache: tension-type |

| 0.049 | Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| 0.047 | Spinal cord lesion below neck: treated |

| 0.044 | Amputation of both arms: long term, with treatment |

| 0.030 | Intestinal nematode infections: symptomatic |

| 0.030 | Anxiety disorders: mild |

| 0.030 | Amputation of finger(s), excluding thumb: long term, with treatment |

| 0.038 | Mastectomy |

| 0.038 | Hearing loss: mild, with ringing |

| 0.037 | Heart failure: mild |

| 0.037 | Angina pectoris: mild |

| 0.035 | Bipolar disorder: residual state |

| 0.033 | Hearing loss: complete |

| 0.033 | Fracture of foot bones: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.033 | Fracture of foot bones: long term, without treatment |

| 0.033 | Distance vision: moderate impairment |

| 0.032 | Hearing loss: severe |

| 0.031 | Intellectual disability: mild |

| 0.031 | Hearing loss: profound |

| 0.031 | Generic uncomplicated disease: lly controlled |

| 0.025 | Fracture of hand: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.024 | Musculoskeletal problems: arms, mild |

| 0.023 | Musculoskeletal problems: legs, mild |

| 0.023 | Hearing loss: moderate |

| 0.023 | Diabetic foot |

| 0.021 | Stroke: long-term consequences, mild |

| 0.021 | Amputation of one leg: long term, with treatment |

| 0.019 | Impotence |

| 0.018 | Ear pain |

| 0.018 | Burns of <20% total surface area or <10% total surface area if head or neck, or hands or wrist involved: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.017 | Fetal alcohol syndrome: mild |

| 0.017 | Dislocation of hip: long term, with or without treatment |

| 0.016 | Fracture of hand: long term, without treatment |

| 0.016 | Claudication |

| 0.015 | COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases: mild |

| 0.013 | Near vision impairment |

| 0.013 | Disfigurement: level 1 |

| 0.013 | Amputation of thumb: long term |

| 0.012 | Motor impairment: mild |

| 0.012 | Dental caries:symptomatic |

| 0.012 | Abdominopelvic problem: mild |

| 0.011 | Parkinson's disease: mild |

| 0.011 | Infertility: primary |

| 0.009 | Other injuries of muscle and tendon (includes sprains, strains, and dislocations other than shoulder, knee, or hip) |

| 0.009 | Asthma: controlled |

| 0.008 | Periodontitis |

| 0.008 | Amputation of toe |

| 0.006 | Infertility: secondary |

| 0.005 | Open wound: short term, with or without treatment |

| 0.005 | Infectious disease: acute episode, mild |

| 0.005 | Hearing loss: mild |

| 0.005 | Anaemia: mild |

| 0.004 | Distance vision: mild impairment |

| 0.003 | Fractures: treated, long term |

[1] Technically these are the results from the 2004 update to the 1990 version, but when you look at where their estimates come from (pdf you see that most just say they're kept unchanged from the 1990 version.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T11:46 (+10)

Thanks for this great summary Jeff!

Here are a couple of comments:

1) I happen to know quite a bit about the rationale behind the GBD 2010 method as I was involved near the end of the process. It is designed to avoid talking about evaluative questions of the quality or value of life and to only talk about the descriptive question of the level of health -- something that doctors are meant to plausibly have more expertise on. This change avoids certain critiques of the method, but I and many other philosophers and economists think that it is quite a bit worse overall and possibly incoherent. At least for effective altruism, we only care about health states in terms of answering normative questions of which option to choose and here we care about the evaluative measures of quality. Notably these come apart from the descriptive ones in cases like intellectual disability and infertility. People don't rate people with these conditions as much less healthy, but they do agree that their lives are made quite a bit worse. When things come apart like this, it is the badness in their lives that should matter. I was more sanguine about this before I read your article as I'd heard there was at least a strong correlation between these new numbers and the old ones, but your quantitative correlation chart shows that it is not that strong. I'd thus use one of the earlier approaches, or one of the many QALY type approaches that have been done in parallel with these DALY ones.

2) Regarding scepticism about the weightings, it is not like there is any other sensible option but to use them (well, one version or another of them). Using one's own intuition about how bad two health states are is obviously worse than at least one of the current aggregate measures, as is considering all ill-health to be equally bad. Rejecting these aggregate health quality weights means using some other form of health quality weight which will be worse. It is OK to think that these quality weight numbers introduce another level of noise into cost-effectiveness -- they do! -- and we don't have any better options but to use them. Also, the noise introduced is not all that much compared to the signal (I'd say it introduces less than a factor of 2, when the data shows many things separated by factors of 100 or more), so the results can still be used for many purposes.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T17:05 (+2)

I'd thus use one of the earlier approaches, or one of the many QALY type approaches that have been done in parallel with these DALY ones.

I agree with this and think it's important enough to highlight.

undefined @ 2014-09-13T04:05 (+7)

I think it's possible to accomplish the desired goals. To do so, we'd need to include information about co-morbidity, secondary conditions, related life problems and general life problems in the data. Here, I explain why including all of this data can help serve goals better.

Consider Including Co-morbidity, Secondary Conditions and Related Life Problems:

Co-morbidity: It's not uncommon for people with a serious illness to have one or more additional illnesses. People can even get two disabling conditions at once. For an example of a disabling disease that tends to co-occur with other diseases: depression, one of the most deadly and disabling diseases for the younger age range, tends to co-occur with anxiety.

Related Life Problems: One serious problem can cause a snowball effect of other problems. In the case of disability, you're likely to experience joblessness, poverty and social issues (like exhausting your social safety net, being treated differently, being seen as unattractive by a partner or potential partners). These can result in worsening the original problem by reducing the finances and social support available.

Secondary Conditions: Being disabled, poor, and having social issues, one might find that they also develop depression and/or anxiety. A stressful life may result in additional health risks on top of that, accelerating the pace at which one's health breaks down as they age.

Why include additional problems?

Some people would not be disabled if they had only one condition, but ended up disabled because they have three or four conditions. These people might be low-hanging apples (easier to get above the disability line) but they could be missed if you don't design a method that's intended to capture their data.

If you want to have data that tells you how bad each person's situation is, we can't use a method that assumes the person has only one serious problem. We need this information for that purpose. We cannot assume that most people in a bad situation have only one disadvantage. Some of them have five or ten.

If what you want was an idea of how disabilities impact people, using a method that assumes only one disability won't give you an accurate picture of the reality of disability.

When people have multiple problems, they may answer questions like the trade-off questions differently. Miserable people may have a difficult time figuring out exactly which of their three problems caused the misery they're experiencing and may attribute some misery to a specific disability when it is actually coming from somewhere else.

Idea: Give them a survey of life problems in general.

I think one of the main reasons altruistic programs designed to help disadvantaged people aren't more successful is because they don't account for the fact that a lot of people who are disadvantaged deal with multiple disadvantages at once. A situation of multiple disadvantages can result in a very tangled web of problems that isn't solved with just one form of assistance. Sometimes one form of assistance might fix a person's whole life because all of their problems were caused by the one disadvantage. Sometimes, things are so brutally tangled that you'd really need to tackle three or four things to get the person out and start seeing real results in terms of happiness and productivity increases.

Why I suggest this survey:

You can look for patterns in this data and create theories like "Such and such disability usually causes poverty, the combination of poverty and disability usually causes depression." and, after investigating this to test your ideas, realize that there are certain things you could target that could solve multiple problems at once. This data could turn up super effective ways of helping.

This data could allow you to get closer to showing your true effectiveness. This is because it's a starting point for quantifying the benefits of solving other problems that were caused by the disability you were treating.

You'd have additional information that will help you work out which people's situations have the most room for improvement. There may be patterns correlated with certain diseases where some diseases tend to cause five additional problems while others cause only one. If your terminal goal is to improve people's lives as much as possible, you'd of course want to consider targeting these.

You'd be able to start looking for multiplier effects between specific problems where one problem causes the other problem to be more difficult to solve. Then we might be able to detect those "tangled webs" that are tough to solve with only one form of assistance. Knowing about some of the "tangled webs" might provide a sort of low-hanging apple to increase effectiveness. For example, say that someone has both a disability and depression. The treatment for the disability takes time and energy. Maybe the person doesn't have enough time and energy to do their part of the treatment because they're depressed. Ensuring that they have an effective depression treatment first could boost effectiveness of the program to treat the disability.

Those lucky enough to have an opportunity to help others sometimes haven't been through anything remotely similar to what the most disadvantaged 10% of the population experiences. Therefore, they may not have a very good idea of what that's actually like and how life for those people actually works. If altruists had a chart showing the distribution of problems across the population, they'd have a clearer picture of the world they're working with and the problems they're trying to solve. If they had notions about "tangled webs" and specific ideas about common webs, and how the most common webs work, they'd be getting closer to an accurate map of the problems they're trying to solve. This information will help altruists avoid a "let them eat cake" situation where they're creating programs that are ineffective because they're assuming the person has other resources available (like a social safety net, adequate funds for treatment supplies, a suitable home in which to do treatments, sufficient energy, etc.) when they actually don't.

Note: There are probably difficulties involved with providing multiple forms of assistance at once which one would need to be aware of before beginning. For instance, some disadvantaged people may not have enough time and energy to solve multiple life problems at one time, so some of those additional forms of assistance may need to be geared for people who are taking on a difficult recovery process already. Some people with disabilities will find some programs difficult to stick to. There's a question of "Which form of assistance should be done first?" By this I mean that you might need to recommend whichever one is more feasible for the person to accomplish given their current time and energy resources, or whichever one will make other forms of assistance easier for them to handle.

A New Quantification System:

If we do enough research to discover which additional problems are caused by disabilities, we can use this as a way of quantifying the level of difficulty the disability causes. Using this, we could create a more objective survey to quantify disabilities that asks them about whether they have certain life problems, secondary conditions, etc. Many of those problems and conditions can be quantified in some way that is far less subjective than "Would you take a 20% risk of death?". Poverty can be quantified as a number of dollars, time poverty as a number of hours, social support as a number of people willing to help (at how many hours per week), and secondary conditions can often be quantified in fairly objective terms as well. By tracking as many problems caused by the disability as possible, I think we can get reasonably close to a clear picture of how bad a disability is.

It seems to me that this might make a good article. I don't have sufficient karma to post it. What do you think, readers?

undefined @ 2014-09-13T05:31 (+3)

This proposal seems similar to Bhutan's use of Gross National Happiness. I agree that it's good for governments to use statistical analysis to figure out what is making their citizens (or ideally, the world's citizens, of course!) better off. Governments already have data on how many citizens are using the disability support pension and have lots of lifestyle data from the census. Anyway, the proposal sounds interesting. Feel free to send me a Google doc with this kind of article to recieve detailed feedback so that we can aim to post it over the coming weeks.

undefined @ 2014-09-14T02:32 (+4)

Wow. When I first came across the Gross National Happiness Index concept, I thought it was a bit fluffy. I had no idea that it was anything more than a simple survey. Now that I have checked out "A Short Guide to Gross National Happiness Index" [1], I see that there's something to learn about here.

Now, I desperately want to get my hands on the raw GNHI data. I can code. Read: I am able to quickly process the data to answer our questions about it. Do we have any connections through which this data can be obtained? I can try emailing them if not, but email addresses on contact pages can be hit or miss.

undefined @ 2014-09-28T13:11 (+1)

I think this comment is one of the best I've read on this forum thus far, and I wish more had read it to upvote it. I want it to become an article, so please email Ryan to make that happen!

undefined @ 2014-09-19T01:28 (+4)

0.011 Infertility: primary

I notice I am confused. My mental model of the average person would definitely choose a 99% chance of life over a 100% chance of life with infertility.

undefined @ 2014-09-19T13:28 (+4)

First, the claim is that infertility is 98.9% as healthy as full health; this part isn't much based on tradeoffs. Which is frustrating, since tradeoffs are more useful for the kind of questions we care about.

But even then, I'm not sure most infertile people would take a 1% chance of death to restore their fertility. Another way of putting it: if the maternal death rate in the US jumped from 28/100,000 to 1,000/100,000 (a level only Sierra Leone hits) how many people would decide not to have kids?

undefined @ 2014-09-19T10:09 (+4)

This is for the reason I outlined in another comment. This revised ranking uses people's judgments of which state is more 'healthy', rather than how good they are. People don't think that being infertile makes people much less 'healthy' even though they think it is bad. The same goes for reductions in intelligence such as via lead poisoning.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T15:03 (+3)

Really interesting post!

Regarding the non-correlation between the different methodologies: isn't it the case that the two methods are not even trying to measure different things. There was a bit of talk of this at the Good Done Right conference, where it seemed like the consensus was that e.g. person tradeoffs try to measure something like the wellbeing associated with health-states, while the newer method simply measures a more removed concept of healthiness. These two may come apart especially in cases of really unhealthy states that do not change your wellbeing significantly such as becoming paraplegic.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T09:04 (+3)

But hold on: how did they turn a large number of responses where people said one disability was more or less healthy than another into weightings on a 0-1 scale where 0 is full health and 1 is death? It turns out that a quarter (n=4000) of the people who took the survey on the internet were also asked the "person tradeoff" style questions used in the 1990 version, which they called "population health equivalence questions". So they first determined an ordering from most to least healthy using their large quantity of comparison data, and then used the tradeoff data to map this ordering onto the "0=healthy 1=death" line.

My understanding is that the large set of comparison data was used to construct a cardinal ordering (via some statistical technique based on the idea that if A is very often preferred to B then B must be substantially worse). The extra data from the population health equivalence questions was purely to work out how to scale this with respect to the 0=full health, 1=death.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T11:30 (+3)

Yes, I thought this too. Something like ELO scores used to generate cardinal rankings for chess players from the ordinal data of their previous match results.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T15:51 (+2)

Elo scores are based on trying to model the probability the A will beat B. They assume every player has some ability, their performance in a game is normally distributed, the player with the higher performance in that game will win, and all players have the same standard deviation. So each player can be represented by a single number, the mean of their normal distribution. If we see A beat B 75% of the time and A beat C 95% of the time, then we could construct normal distributions that would lead to this outcome and predict what fraction of the time B would beat C.

Trying to apply this to disease weightings is modeling there as being some underlying true badness of a disease that each person has noisy access to. This means that if A and B are close in badness we will sometimes see people rank A worse and other times rank B worse, while if A and B are far apart we won't see this overlap. The key idea is that the closer together A and B are in badness, the less consistent people's judgements of them will be. But look at this case:

- Condition A is having moderate back pain, and otherwise perfect health.

- Condition B is having moderate back pain, one toe amputated, and otherwise perfect health.

Almost everyone is going to say B is worse than A, and the people who rank A worse probably misunderstood the question. But this doesn't mean B is much worse than A; it just means it's an easy comparison for people to make, x vs x+y instead of x vs z.

Do we just assume this is rare with disability comparisons? That consistency is only common when things are far apart? Is there a way to test this?

undefined @ 2014-09-12T17:03 (+1)

I agree that this is not terribly well-founded.

I asked one of the architects behind the method about this issue. The answer boiled down to an agreement that this could cause problems in principle, but that in practice the overall badness of a condition was based on many comparisons, some of which might be easy but some of which will be hard, so it comes out okay on average.

undefined @ 2014-09-12T18:32 (+2)

I'm extremely pleased to see mental illness and addiction considered.