We need a new Artesunate - the miracle drug fades

By NickLaing @ 2025-02-23T11:38 (+78)

TLDR: After artesunate rose from an obscure Chinese herb to be the lynchpin of malaria treatment, increasing resistance means we might need a fresh miracle.

Back in 2010 I visited Uganda for the first time, a wide eyed medical intern in the Idyllic Kisiizi rural hospital. In my last week malaria struck me down, but there was a problem – a nationwide shortage meant that no adult artesunate doses remained. Through an awkward mix of white privilege and Ugandan hospitality, I was handed the last four children’s doses to make up one adult dose. Even in my fever dream, I pondered the fate of those 4 kids who would miss out because of me…

Act 1 – The Origin

In the midst of the Vietnam war, a fierce arms race was afoot. But not for a killer – for a life saver. Troops died from more than just bullets, bombs and shrapnel – a nefarious killer roamed, and the drugs of the day weren’t good enough. “The incidence (of malaria) in some combat units..., approached 350 per 1,000 per year”. Chloroquine and quinine took too long to cure malaria and side effects were rough. Resistance to quinine was on the rise, “14 days proved inadequate to effect a radical cure, and there was a 70 to 90 percent rate of recrudescence within a month.” Soldiers might not die of malaria but could be out of action for weeks.

Both sides set their best scientists to the race. The Americans discovered that if you added an extra drug pyrimethamine, cure rates were higher and recovery was quicker -a useful development but hardly a game changer. The Chinese though had a secret weapon.

I’m proud that EAs lobby to normalise “challenge studies” as a quicker way to find cures than laborious multi-year RCTs. China's Tu Youyou was putting them to great use to help the North Vietnamese cause. Armed with malaria infected mosquitos and 2,000 traditional herbs, she wondered whether there was any merit in thousands of years of traditional Chinese medicine. After culling the initial list of 2000 to the 380 most promising herbs, she started infecting and treating mice. Only one herb actually worked for malaria, but that one was enough. She then volunteered to be the first human subject.

As much as nature cruelly dealt us the malaria parasite, nature also gifted us our two best cures. “Quinine” bark was discovered to have antimalarial properties perhaps 2,000 years ago and has been refined over the centuries. And Youyou’s jackpot? The humble Artemisin "Wormwood" plant – an almost absurdly effective malaria cure with barely any side effects.

Act 2 - The Deadly Delay

After Youyou’s discovery, the Artemisin timeline would ideally have gone something like this.

1973 – Discovery

1975 – Randomised trials in Asia and Africa

1978 – Production increases

1980 – Artesunate takes over Qunine as the drug of choice and we all rejoice!

INSTEAD the timeline went

1973 – Discovery

1981 - Discovery Presented to WHO

.......

…….

…….

1996 - Trials in African and Asia show artemisin derivatives no worse than Quinine

1998 – Cochrane review shows artemisin derivatives no worse than Quinine

2003 – Small RCT shows artesunate “as effective as quinine” for severe malaria

2005 - SEAQUAMAT study in Southeast Asia shows clear mortality reduction in adults

2010 - AQUAMAT study in Africa shows even larger mortality reduction in children

2011 - WHO finally recommends injectable Artesunate as first line for severe malaria

What caused this long, tragic delay isn’t clear, but we do know that the Chinese didn’t broadcast their miracle to the world, while the West also didn’t show enough interest despite being aware of the drug.

Even the 2005 East Asian based “SEAQUAMAT” study which showed a 34% mortality reduction over quinine didn’t stimulate immediate uptake. We instead insisted on another “AQUAMAT" study in African Children which completed another 5-years-of-wasted-lives later. In 2011 The West finally woke up, a chilling 38 years after Youyou’s discovery. In 2015, 42 years after her stroke of genius we finally gave Tu Youyou the Nobel prize she deserved, though she remains a relatively little known and celebrated Nobel winner.

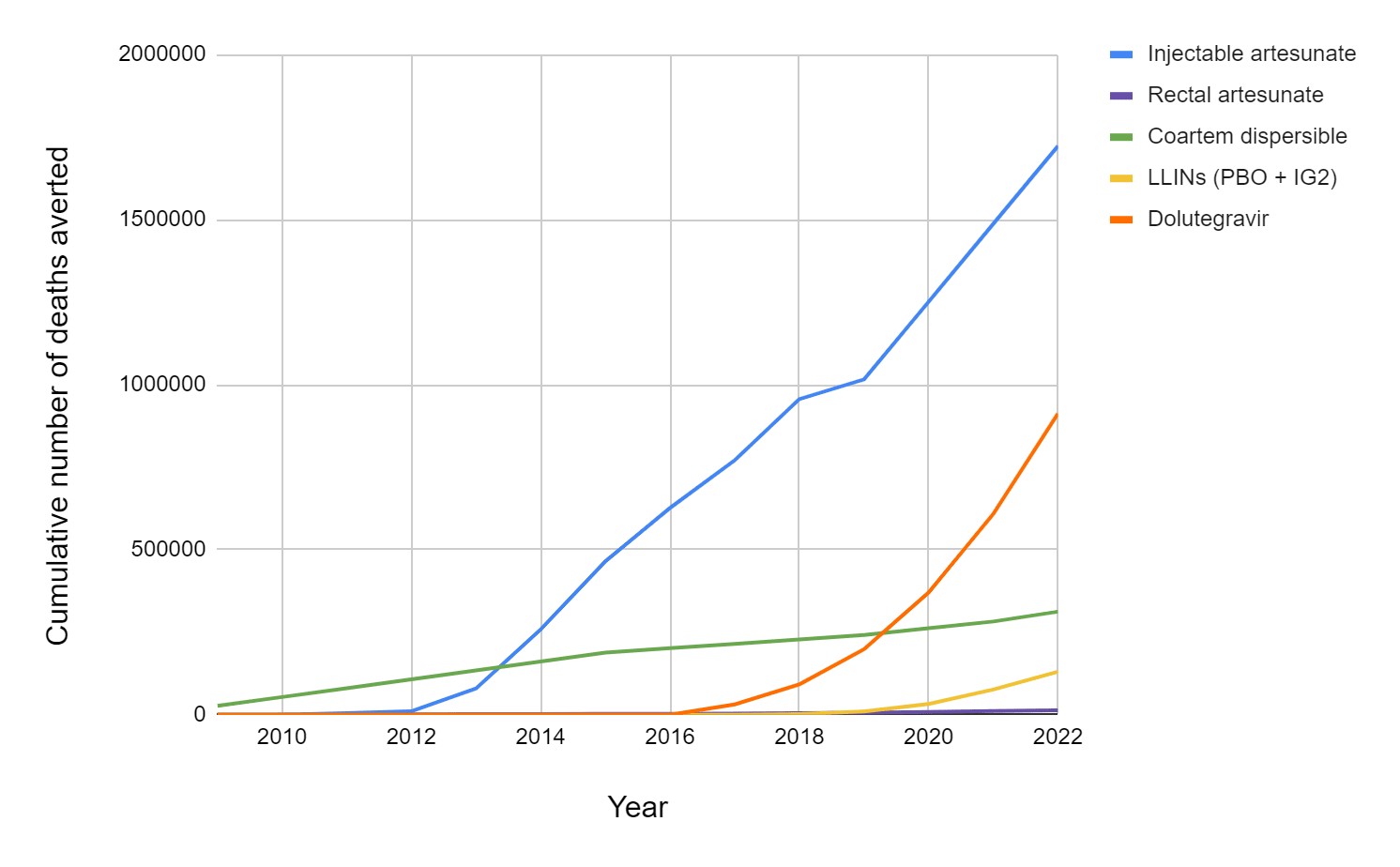

Rethink priorities calculated that Artemisin derivatives might have saved 2 million lives [1] in the 10 years between 2012 and 2022. Does this mean that at least 5 million more could have been saved had we not delayed for 30 years between 1980 and 2010?

Only 10 years after we heroically co-ordinated to eradicate smallpox, through a combination of Chinese Protectionism, Western skepticism and perhaps just apathy, we missed the artemisinin boat and allowed untold unnecessary suffering. We humans are capable of both incredible good and unfathomable folly.

Act 3 - The Miracle

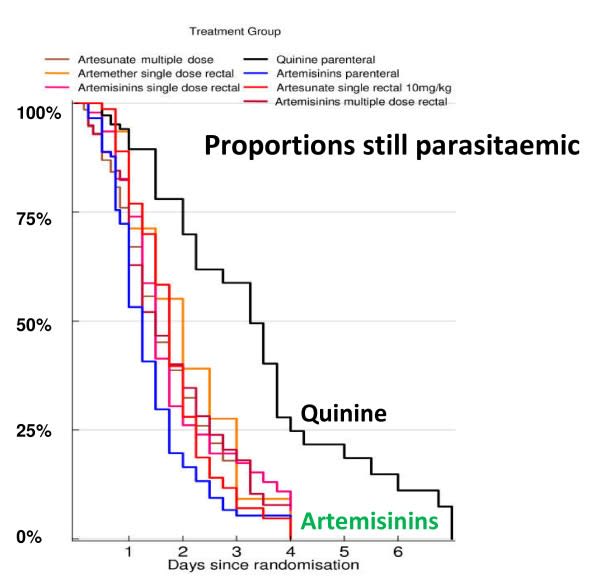

But despite this delay, the miracle stands – and miracle is hardly too strong a word. Artesunate clears those pesky parasites more than twice as quickly as quinine. Every African doctor has seen kids seizing, unconscious, gasping for air brought back from the brink less than an hour after the magic injection. I’m not sure there’s any antimicrobial drug which illicits a more breathaking recovery [2]

White, N. The parasite clearance curve. Malar J 10, 278 (2011).

As Artemisinin comes from a plant ramping up production wasn’t easy, we needed thousands of acres of plants. Back in 2010 when I stole the last children's doses, we still couldn’t produce enough artemisinin to treat all 10 million malaria cases every year. Through artificial synthesis, we now produce enough artemisinin to treat every malaria case in the world.

Act 4 - The Wormwood wilts?

In 2025 artemesin’s flower has begun to wilt. Resistance first emerged in South-East Asia before spreading to Africa. Artesunate still works, but takes longer to clear the parasites and the drug’s power wanes. We’ve now reached a tipping point where for the first time, normal artemisin doses don’t always cure malaria.

As we speak, in combination with other medication artesunate still cures over 99.9% of malaria cases - if a little slower than before. But we don’t know when that will become 99%, then only 90% at which point we’ll need alternatives. We have stop-gap measures. Some suggest longer medication courses, rotating our dual therapies, or even adding a 3rd drug to the treatment cocktail – a blunt and expensive instrument but ont that could buy us another 10 years.

Combined with climate change, increasing resistance to LLINs and reduced international funding, this emerging resistance might even be a small part of why malaria progress has stalled over the last 5 years.

The wormwood wilts…

Act 5 - A fresh miracle?

One might argue that this is all window dressing to the perfect malaria vaccine, yet that panacea still feels distant. Current vaccines might with perfect implementation at best halve malaria mortality. But unless we see another breakthrough soon, If we don’t find a new drug we might even have to run back to the substandard quinine.

I sure hope we’re turning over every leaf both literally and digitally. Perhaps we’ll round out the botanical trifecta with a cloud forest cure. Or maybe through “AlphaMal” we’ll synthetically AI-our-way out of this pickle. While Bill Gates bets 400 million on a TB vaccine and OpenPhil and partners 100 million on lead elimination, perhaps we need to future proof ourselves from the unthinkable - that malaria treatment could soon be far less effective.

Encouraging work is on the go. A Swiss outfit "Medicines for malaria venture" leads the way with funding from 10 National Aid bodies (USAID is still listed on their website...) and you guessed it - the Gates Foundation. Two new medications with the catchy names SJ733 and MED6-189 [3] show promise but are unproven. While we pump billions into malaria vaccines, maybe we should shuffle a few hundred million more towards a new cure as well?

We might just need a fresh miracle.

- ^

I think they might be overstating this a little, but regardless Artesunate has saved LOTS of lives

- ^

Outside of infectious disease injecting glucose for low blood sugar and naloxone for opiod overdose are even more impressive

- ^

Inspired by a compound from a marine sponge!

Henry Howard🔸 @ 2025-02-23T12:13 (+30)

In 2016 I took part in a novel drug trial in Brisbane, Australia that injected me (and about 6 other men) with the Plasmodium falciparum strain of malaria and then treated us with a new medication called SJ733. The development of SJ733 was funded, I was told, through Bill Gates' Medicines for Malaria Venture. The paper about this trial (and some other trials) came out in 2020: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32275867/

Results were positive!

Seems like work on it continues: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35598441/

I gave the $2880 they gave me to the Against Malaria Foundation. It's one of the best things I've ever done.

NickLaing @ 2025-02-23T15:03 (+10)

Nice one man such a cool thing for you to do, will put a note on new initiatives to find drugs in the article too, should have included that originally anyway!

Linch @ 2025-02-24T23:53 (+9)

Genuinely, thank you for your service.

jwatowatson @ 2025-03-01T05:49 (+10)

The story of artemisinin resistance is important and worth telling. Artemisinin resistance is probably one of the major malaria related public health emergencies in Africa right now.

However, this story entirely confuses the main issues and is riddled with factual errors. I would suggest the author retracts it and consults with experts to write an accurate version.

Some of the major problems/factual errors:

- There is no distinction made between the different uses of the artemisinin derivatives (artesunate, artemether, arteether, dihydroartemisinin being the main ones). Artesunate is primarily used for the treatment of severe malaria (injectable or rectal). But artemisinin derivatives are also used in combination with slowly eliminated partner drugs (lumefantrine, amodiaquine, mefloquine) to treat uncomplicated malaria (oral treatment). Injectable (and rectal) artesunate are life saving drugs for severe malaria but ACTs (artemisinin-based combination therapies) have had a huge impact on malaria attributable mortality because they replaced chloroquine for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. See the letter by Ataran et al from 2004. ACTs are not even mentioned in the timeline! They were being used in Southeast Asia by the late-90s following pivotal trials.

- The paragraph on the Vietnam war makes it sound like quinine was the main antimalarial drug in use during the Vietnam war. Chloroquine had been discovered in 1934, and was developed after WW2. It was very widely used (even put in table salt in Cambodia). Chloroquine was a remarkably effective drug but first reports of resistance were in 1957 on the Thailand/Cambodia border Piperaquine, mefloquine, sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine were developed in the 1950s/1960s.

- "2003 – Small RCT shows artesunate “as effective as quinine” for severe malaria". Not only does this completely ignore the development of ACTs (recommended by WHO as first line treatment in 2006 after the Attaran letter), but this was not the first trial of artemisinin derivatives in severe malaria. The development of artemisinin derivatives given parenterally for severe malaria was much more complex. Initially artemether was chosen as the candidate drug. Two large trials (over 500 patients in each) published in 1996 (one in Africa, one in Asia) showed that artemether was as good as quinine. However, because of its pharmacology (artemether is variably absorbed) it wasn't clearly better. A trial done between 1996-2003 in Vietnam showed that artesunate cleared parasites faster due to better absorption, this then led to the SEAQUAMAT study. So the history as presented is wrong and misleading.

- "artesunate still cures over 99.9% of malaria cases": this is meaningless. Artesunate or any artemisinin derivative is not given on its own to treat malaria. The therapeutic objective in severe malaria is to save life (around 5-20% of patients still die following IV artesunate, depending on their severity at presentation). The therapeutic objective in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria is to stop progression to severe illness and clear all parasites from the body. The artesunate component on its own does not clear all parasites when given over 3 days (even without resistance). The brilliant idea of ACTs is that by combining a fast acting but rapidly cleared artemisinin derivative with a slow acting but slowly cleared partner drug, you leave only a few parasites for the partner drug to clear up. This means that even when the partner drug doesn't work very well, in combination with an artemisinin derivative it can treat the infection. Artemisinin resistance means that there are more parasites that the partner drug needs to clear and so emergence of partner drug resistance occurs. Then the ACT fails to treat the infection. This is what has happened in Southeast Asia. Lumefantrine is the partner drug in around 70% of all treatments used in Africa (artemether/lumefantrine, known by the brand name coartem). If lumefantrine resistance emerged, this would be a major disaster.

- "adding a 3rd drug to the treatment cocktail – a blunt and expensive instrument but one that could buy us another 10 years." No this is wrong. New drugs currently in development are being developed as "triple" therapy. There are good pharmacological reasons for this around prevention of the emergence of resistance.

In summary, this article is highly misleading on the history of the development of the artemisinins into usable treatments for malaria.

NickLaing @ 2025-03-04T19:34 (+9)

Hi James and thanks for posting here on the forum, appreciate someone who is obviously a m malaria expert weighing in here with this useful feedback. I will say I was aware of much of the factual information in your feedback, but chose to leave it out for storytelling purposes - for better or worse.

Overall I was going for a short, simplified narrative article which briefly walked through 5 "acts" in the story of artesunate, while highlighting the incredible discovery story, pointing out that we may have unnecesarily delayed the mass roll out of artemisin treatment and the emerging resistnace issues. I’m writing for a general audience so I didn't focus on scientific details or get into the weeds, while doing my best to not to be misleading . Of course I compromised at times to bring the story out more vividly. I would argue that I make few factual errors, rather I missed out some aspects of the story that could be considered important. I’m interested if you disagree with any of my major points in the article, besides the important scientific information that I omitted? You write that I "confuse the main issues" and I'm interested in what you think those main issues are?

Thanks to your great feedback I've made a few changes based on your feedback to be more precise - I suspect you won’t be completely satisfied as I still leave out much detail but I hope it helps.

- I didn’t want to get into the nitty gritty of treatment during the war (simplicity again), but you’re right that for much the war chloroquine was dominant. I’ve changed the wording to to “Chloroquine and quinine took too long to cure malaria and side effects could be rough”. I wonder what you make of the US army’s reports of both apparent chloroquine and Quinine resistance during the war? My main point here was that the Vietnam war stimulated the development of artemesin derivatives.

- I’ve added in those 1996 studies to the timeline thanks!. This only further adds in my mind to demonstrate how slow we were to figure out how much better artemisin derivatives could be than the status quo. I found these 2 studies super interesting as the signal in both of them was leaning towards artemether being better than quinine (although of course not statistically significant). Unfortunately here in Northern Uganda we still use artemether injections for some of our patients here that can’t afford artesunate (aware that it is not as good), as artemether is less than half the price of artesunate. Fortunately in only the last 2 years, artesunate prices have reduced by about 30% which is great so we are using less artemether than ever.

- I chose to leave out the combination treatment part of the story (see below for reasons), but for accuracy’s sake in the final paragraph have added the combination therapy point and changed to “In combination with other medication, artesunate cures over 99%...”

A little pushback

- You're right that I didn't get into differentiating between the different artemesin derivatives. Although this is a little imprecise, I don’t think explaining the nature of these different derivatives is a critically important piece of information for the story. Again I’m simplifying for storytelling reasons.

- I considered describing the combination therapy part of the story, which I agree is important, but decided to leave it out because the injectable artesunate seems to have had a far more important mortality impact than co-artem, and it would have meant telling a slghtly confusing parallel story ;). Feel free to push back here and I agree there is a good argument for adding them to the story - if I wrote a longer article I would have.

- This Rethink Priorities research here estimates that injectable artesunate saved about 1.7 million lives by 2022 while co-artem saved abuot 300,000. This would mean Artesunate is responsible for 85% of the lives saved by artemisin derivatives and co-artem only 15%. This makes sense to me as artesunate provides a large mortality benefit in severe malaria, while other medications if taken properly cure malaria almost as effectively as co-artem. I agree there are many other benefits from co-artem in uncomplicated malaria (side effects, shorter course, faster clearance) and there is a mortality benefit vs alternatives, but far less extreme than for artesunate.

- Much of the co-artem development story happens in Southeast Asia, which while important accounts for under 5% of malaria deaths.

3) don’t really understand your disagreement with my statement here "adding a 3rd drug to the treatment cocktail – a blunt and expensive instrument but one that could buy us another 10 years." You write "No this is wrong. New drugs currently in development are being developed as "triple" therapy. There are good pharmacological reasons for this around prevention of the emergence of resistance.”

What's "wrong" about my statement here exactly? The Lancet article I quoted discusses the idea of adding a third drug to artemether-lumefantrane as you say, and yes its to avoid the emergence of resistance. It will be expensive to add a third drug and I consider a 3 drug combination a bit of a sledgehammer/blunt tool. Perhaps we largely agree here?

Thanks again for the feedback and I hope to hear more from you here on the forum :).

jwatowatson @ 2025-03-05T15:29 (+3)

I disagree with point 2. ACTs have had a huge impact on malaria mortality and morbidity, primarily because they are so effective, well tolerated, and replaced a completely failing drug (chloroquine). ACTs have lasted in Africa >20 years before starting to succumb to resistance. They have had an enormous impact.

The Rethink Priorities estimate concerns coartem dispersible only, compared to a counterfactual of receiving crushed tablet formulations of Coartem. Two problems: Coartem is the Novartis brand name for artemether lumefantrine (AL), and the dispersible is only a proportion (kids under 3? Not sure about this point) of all AL treatments. And the counterfactual is still an ACT! Novartis only supplies around 10% of all AL. AL is about 70% if all ACTs.

The correct counterfactual question are: how many kids would die from malaria if quinine was still first line treatment for severe malaria; and how many kids would die from malaria if ACTs did not exist (eg if treatment for uncomplicated malaria only used existing non artemisinin drugs). The second counterfactual is really hard to estimate with any confidence because ACTs were such a massive revolution in the treatment of malaria.

To put severe malaria versus uncomplicated malaria in perspective: donor funded procurement of ACTs in 2022 was 257M (Chai estimates). For injectable & rectal artesunate this was 45M (almost 6x difference). The fact that AL (or ACTs in general) were primarily developed and tested in Asia is irrelevant: their use today is in Africa.

Regarding point 3: the future of antimalarial treatment for uncomplicated malaria will be triple combination therapy. For the next 5 to 10 years this will likely be with existing drugs, possibly in combination with new drugs (e.g. ganaplacide). Triple therapy is not a blunt tool, it is what is needed to prevent the emergence of resistance.

Rasool @ 2025-02-23T14:22 (+10)

This section from Tu Youyou's Wikipedia page is incredible:

As Tu also presented at the project seminar, its preparation was described in a recipe from a 1,600-year-old traditional Chinese herbal medicine text titled Emergency Prescriptions Kept Up One's Sleeve. At first, it was ineffective because they extracted it with traditional boiling water. Tu discovered that a low-temperature extraction process could be used to isolate an effective antimalarial substance from the plant; Tu says she was influenced by the source, written in 340 by Ge Hong, which states that this herb should be steeped in cold water. This book instructed the reader to immerse a handful of qinghao in water, wring out the juice, and drink it all. Since hot water damages the active ingredient in the plant, she proposed a method using low temperature ether to extract the effective compound instead.

Scott Smith 🔸 @ 2025-02-27T00:08 (+5)

Thank you Nick. A lot of interesting information for an accessible 5-minute read.

As we speak, artesunate still cures over 99.9% of malaria cases - if a little slower than before. But we don’t know when that will become 99%, then only 90% at which point we’ll need alternatives.

I'm trying to get my head around the meaning of these numbers. The questions below are largely academic (no goal in mind), surely difficult, and likely dumb, so please feel no pressure to devote valuable time :)

(1) Are these cure rates in reference to the outcome of Therapeutic Efficacy Studies (TES) as described in this WHO document (Section 4.1) and where the outcome is an "adequate clinical and parasitological response (ACPR)" (p. 11 of that document)?

If it is:

(2) What is your best estimate for how often ACPR would be "achieved" without treatment?* I believe this would be difficult to answer. My estimate right now based off close to zero rationale: 4% (95% CI: 0.25% - 60%).

(3) What would you estimate the effect on saving a child's life would be in a drop from 100% to 90%?* Maybe can be quantified as (but you likely have a better way): For every 1000 children who come into a clinic for malaria treatment, how many would survive if (a) artesunate is administered versus if (b) no treatment was provided, given (i) 100% efficacy versus (ii) 90% efficacy.

My suspicion is that the ratio of p(ACPR | artesunate) : p(ACPR | no treatment) underestimates the effect on mortality (and severe malaria) due to the binary outcome measure not capturing benefits from artesunate reducing without eliminating the degree of parasitaemia(?)

Thanks again.

*in high transmission areas where inclusion criteria is "patients with fever, aged 6–59 months, with an asexual parasitaemia ranging between 2000 and 200 000 parasites/μL"

NickLaing @ 2025-03-04T19:44 (+5)

Thanks Scott interesting questions

1) TO answer this I'm just saying that an artemisin derivative plus another medication (co-artem) will still cure malaria completely almost all of the time, even if it takes longer

I don't have the answer to 2 or 3 exactly and dont' have the time to look into it but you're thnking along the right lines. For every 1,000 children who came into a clinic for malaria, at least 950 would survive with no treatment, but even those that survive are likely to encounter a range of problems such as anemia, low energy, recurrent fevers etc. Also like you say people would be more prone to dying from other diseases as well after being weakened from malaria, as is well established in the case of diarrheal disease. Malaria actually weakens immunity directly as well. If I recall correctly somewhere between 1 in 10 and 1 in 20 severe malaria cases has co-infection with a bacterial infection.