Summary thread: 'Essays on Longtermism' Chapters

By Toby Tremlett🔹 @ 2025-09-08T09:36 (+34)

To enter the 'Essays on Longtermism' competition, you need to write a post responding to one of the chapters in the collection (or a theme from across the collection).

But there are a lot of essays in the collection (well done GPI).

In this thread, authors from the collection will introduce their chapters, and highlight problems or further questions that they still have about the contents. Hopefully, this will help you (the possible entrant) decide which essay to respond to!

If you aren't an author from the collection, but a specific essay really interests you and you'd like to see people take the ideas and run further, feel free to use this thread to argue for it.

Update: I'll leave this thread up until EOD on the 19th of September, to give the authors time to write their comments.

Shakked Noy @ 2025-09-08T15:25 (+37)

Hi everyone! I’m Shakked, a PhD student in economics at MIT, and this comment summarizes The Short-Termism of ‘Hard’ Economics, a chapter in Essays on Longtermism that I coauthored with my dad Ilan, a Professor of Economics at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

The chapter is about the academic economics profession. We think the profession has not yet, and will not in the foreseeable future, produce much useful longtermist research as part of the mainstream research it systematically produces, publishes in top journals, and rewards professionally. (Individual economists might still produce useful longtermist research as voluntary side-projects, as we note below.) In the chapter, we argue that this is because the profession is subject to a constricting set of methodological norms that preclude the kinds of research that might be useful from a longtermist perspective.

Specifically, we think that useful longtermist research - by virtue of its speculative nature and the thin historical evidence base it has to rely on - will tend to have a few attributes. It will draw on a variety of sources of empirical evidence, including expert forecasts, narrative historical commentaries, quantitative projections, interviews and focus groups, and so on. It will make theoretical arguments that are often institutionally-specific or draw on a diversity of concepts. As a consequence of these diversities of evidence and argument, it will tend to be multi-disciplinary.

Almost all of the above are ruled out by the current methodological norms of the academic economics profession. An obsession with methodological “hardness” - a concept which George Akerlof says is used to “classify sciences according to a hard–soft hierarchy, with physics at the top and sociology, cultural anthropology, and history at the bottom” - results in the imposition of severe restrictions on the kinds of work economists accept. On the empirical side, this means that only carefully identified causal estimates are permissible forms of empirical evidence. This rules out descriptive, explanatory, or predictive work and narrows attention to topics where sufficiently large micro datasets are available, implicitly narrowing the geographic and temporal scope of research. On the theoretical side, this involves a focus on mathematical generality and technical sophistication and difficulty, which precludes both arguments that are impossible to formalize mathematically and arguments that are trivial to formalize.

The chapter goes into a lot of detail about the exact shape of the norms and applies them to three areas of longtermist interest: long-term decision-making, climate change, and AI.

The chapter was written in mid-2022, before the release of ChatGPT, so the past 3 years have constituted an interesting out-of-sample test of the arguments and predictions we make. We think the chapter has held up pretty well. There’s been an enormous growth in research on AI in economics; the majority of this new research has taken the form of the kind of short-termist empirical or backwards-looking theoretical work we describe in the chapter. There’s also been an increase in interest in longtermist perspectives on AI, including an upcoming NBER conference on the Economics of Transformative AI, as well as some examples of genuinely useful research. But so far our sense is these developments show no sign of penetrating the top journals or professional reward processes.

Toby_Ord @ 2025-09-15T12:11 (+30)

My chapter, Shaping Humanity's Longterm Trajectory, aims to better understand how reducing existential risk compares with other ways of influencing the longterm future. Helping avert a catastrophe can have profound value due to the way that the short-run effects of our actions can have a systematic influence on the long-run future. But it isn't the only way that could happen.

For example, if we advanced human progress by a year, perhaps we should expect to see us reach each subsequent milestone a year earlier. And if things are generally becoming better over time, then this may make all years across the whole future better on average.

I've developed a clean mathematical framework in which possibilities like this can be made precise, the assumptions behind them can be clearly stated, and their value can be compared.

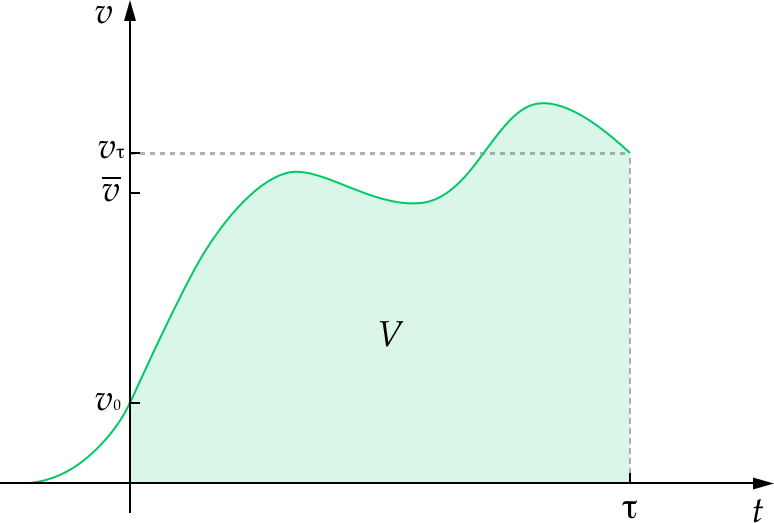

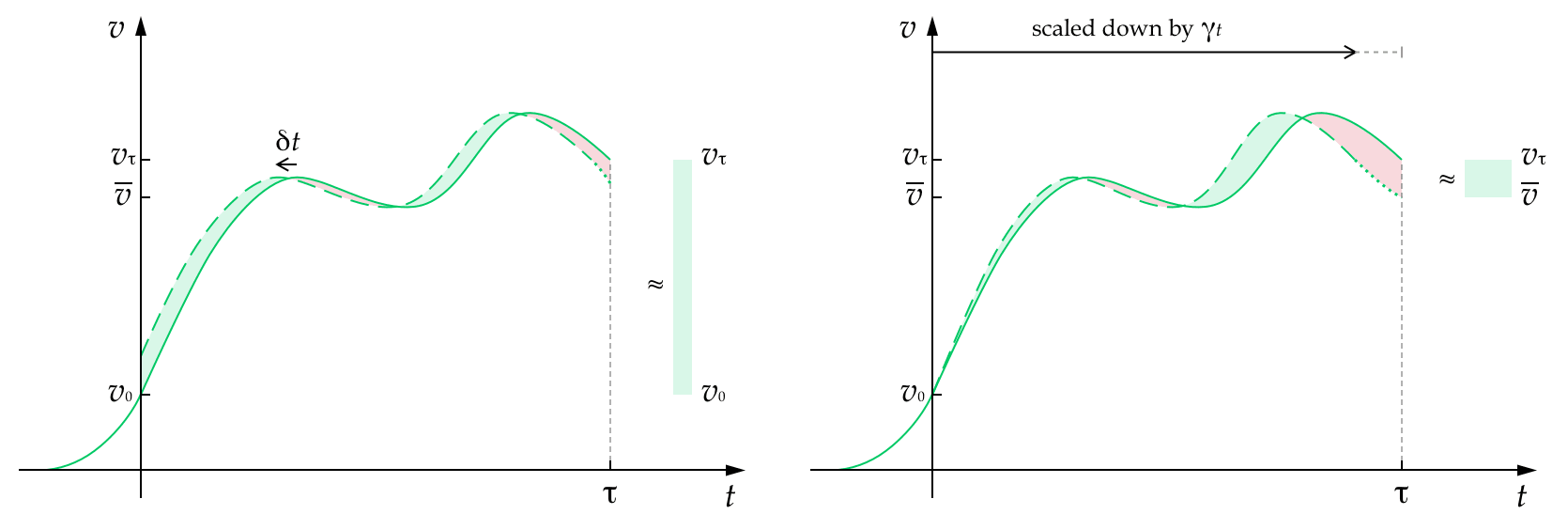

The starting point is the longterm trajectory of humanity, understood as how the instantaneous value of humanity unfolds over time. In this framework, the value of our future (V) is equal to the area under this curve and the value of altering our trajectory (V) is equal to the area between the original curve and the altered curve.

This allows us to compare the value of reducing existential risk to other ways our actions might improve the longterm future, such as improving the values that guide humanity, or advancing progress.

Ultimately, I draw out and name 4 idealised ways our short-term actions could change the longterm trajectory:

- advancements

- speed-ups

- gains

- enhancements

And I show how these compare to each other, and to reducing existential risk.

My hope is that this framework, and this categorisation of some of the key ways we might hope to shape the longterm future, can improve our thinking about longtermism.

Some upshots of the work:

- Some ways of altering our trajectory only scale with humanity's duration or its average value — but not both. There is a serious advantage to those that scale with both: speed-ups, enhancements, and reducing existential risk.

- When people talk about 'speed-ups', they are often conflating two different concepts. I disentangle these into advancements and speed-ups, showing that we mainly have advancements in mind, but that true speed-ups may yet be possible.

- The value of advancements and speed-ups depends crucially on whether they also bring forward the end of humanity. When they do, they have negative value.

- It is hard for pure advancements to compete with reducing existential risk as their value turns out not to scale with the duration of humanity's future. Advancements are competitive in outcomes where value increases exponentially up until the end time, but this isn't likely over the very long run. Work on creating longterm value via advancing progress is most likely to compete with reducing risk if the focus is on increasing the relative progress of some areas over others, in order to make a more radical change to the trajectory.

The paper has lots of nice diagrams, but they are low-resolution in the current official version, so you may want to read my own PDF here.

Dr Heather Browning @ 2025-09-17T11:09 (+29)

Hi all,

Here's a summary of the chapter written by me and Walter Veit, 'Longtermism and Animals'.

Up to now, discussions on longtermism have centred almost entirely on humans. In our chapter, we argue that this is a mistake.

Nonhuman animals already outnumber humans by orders of magnitude - billions of farmed terrestrial vertebrates, trillions of wild-caught fish, and even more wild animals (especially if we count invertebrates). More animals are killed by humans annually than the number of humans who have ever existed. If the long-term matters because of the sheer scale of future humans, then it matters at least as much, if not more, because of the even greater number of animals likely to exist. In addition to this, many of their lives contain a significant amount of suffering, both in agriculture and in the wild. Unless we assign implausibly low weight to animal welfare, their interests are likely to dominate the moral calculus in both short-termist and longtermist thinking. Even if not, they definitely need to be counted.

In light of this, we discuss a range of possible interventions that could improve the long-term future for animals. The first set of these are actions to change the number of animals (i.e. decrease the number of net-negative and increase the number of net-positive lives), such as ending factory farming, reducing some populations of wild animals and supporting the growth of others. Other actions are those aimed at improving the lives of those animals that do come into existence, including improving the conditions of animal agriculture, intervening to prevent suffering of wild animals, and use of technological or genetic interventions to enhance animal wellbeing.

We emphasise that probably the most important and effective interventions in the long term will be those that involve value change, as these will ensure that animals’ interests are persistently valued in institutions and policies. Many of the most impactful actions for animals involve shifting human attitudes and institutions toward lasting respect for animal welfare. If our current moment is one in which values risk becoming “locked in”—for example, through the design of AI systems—then ensuring animals are included is urgent.

The upshot is not that we already know which interventions are best. Rather, it’s that excluding animals from longtermist thought leaves out what may be the largest source of moral value (or disvalue) in the future. Bringing animals into the conversation will change how we think about what matters and how we evaluate possible interventions. We encourage anyone interested in longtermism and/or animal welfare to think about how animals should be included in longtermist thinking as this should be a key part of the research agenda.

Krimsey @ 2025-09-18T00:17 (+2)

The number of animals affected is staggering. I agree, they should be considered as priority. And reducing our consumption of them can help human health and environment, too. Lots of positive "trickle-down" effects for humans.

Gustav Alexandrie @ 2025-09-10T11:22 (+27)

Hi everyone! Below is a summary of the chapter that Maya Eden and I wrote for Essays on Longtermism.

What socially beneficial causes should altruists prioritize if they give equal ethical weight to the welfare of current and future generations? Many have argued that, because human extinction would result in a permanent loss of all future generations, extinction risk mitigation should be the top priority. We call this the long-run argument for extinction risk mitigation.

In Alexandrie and Eden (2025), we evaluate the long-run argument for extinction risk mitigation through the lens of population models. Below we outline what we take to be the two key takeaways of the paper.

Takeaway 1: The long-run argument for extinction risk mitigation relies on the assumption that the global population would partly recover after a non-extinction catastrophe

We present a theoretical framework for quantifying the cost-effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing negative shocks to the size of the global population. A heuristic implied by this framework is that the undiscounted cost-effectiveness of reducing the risk of a negative population shock is proportional to the ratio of future lives lost (in percentage terms) to current lives lost (in percentage terms). We call this the long-term value ratio.

Let us compare the cost-effectiveness of reducing extinction risk with that of reducing the risk of a catastrophe that would kill 10% of the population. Since human extinction would result in a loss of 100% of current lives and 100% of future lives, the long-term value ratio of extinction risk mitigation is 1. Now, a catastrophe that would kill 10% of current lives may result in a loss of less than 10% of future lives (if there is recovery) and more than 10% of future lives (if there is amplification). Therefore, if there is recovery, the long-term value ratio of mitigating the 10%-catastrophe is higher than 1; if there is amplification, it is less than 1. This example shows that (partial) recovery is necessary for extinction risk mitigation to be more cost-effective than other types of catastrophic risk mitigation.

Takeaway 2: Population models suggest that nothing guarantees recovery after a negative population shock

We distinguish between two different negative shocks to the size of the global population. A pure population shock is an event that kills some fraction of the world population without having much direct impact on other factors of production (e.g., a pandemic that kills people, but doesn't destroy physical capital). An all-factor shock is an event that destroys all factors of production in equal proportion (e.g., an asteroid that kills the same fraction of people as it destroys physical capital).

Pure population shocks and all-factor shocks have different implications for recovery dynamics after the shock. We consider three models of such fertility dynamics: the social determinants model, the Barro-Becker model, and the Malthusian model. For pure population shocks, only the Malthusian model unambiguously implies that the population would recover after a shock. For all-factor shocks, none of the models imply that such recovery would occur, at least if natural resources are destroyed in the same proportion as population and physical capital. This is because the population models we consider imply that the economic determinants of fertility are invariant to the scale of the economy, which is all that is affected by all-factor shocks.

Conclusion

The long-run argument for prioritizing extinction risk mitigation relies on the assumption that the global population would partly recover after a non-extinction catastrophe (Takeaway 1). However, population models suggest that nothing guarantees that such recovery would occur after a non-extinction catastrophe (Takeaway 2). Together, these two takeaways provide a challenge to the long-run argument for prioritizing extinction risk mitigation.

Stefan_Schubert @ 2025-09-22T19:08 (+15)

This is a summary of Temporal Distance Reduces Ingroup Favoritism by Stefan Schubert, @Lucius Caviola, Julian Savulescu, and Nadira S. Faber.

Most people are morally partial. When deciding whose lives to improve, they prioritise their ingroup – their compatriots or their local community – over distant strangers. And they are also partial with respect to time: they prioritise currently living people over people who will live in the future. This is well known from psychological research.

But what has received less attention is how these psychological dimensions interact. In this chapter, we study this question. Specifically, we ask how time affects ingroup favouritism. Suppose you’re asked to support one of two charities:

- A national charity, supporting your compatriots

- A global charity, supporting whoever needs the money the most, regardless of country

Now suppose that these beneficiaries are future people who will live hundreds or thousands of years from now. How would that affect your choice?

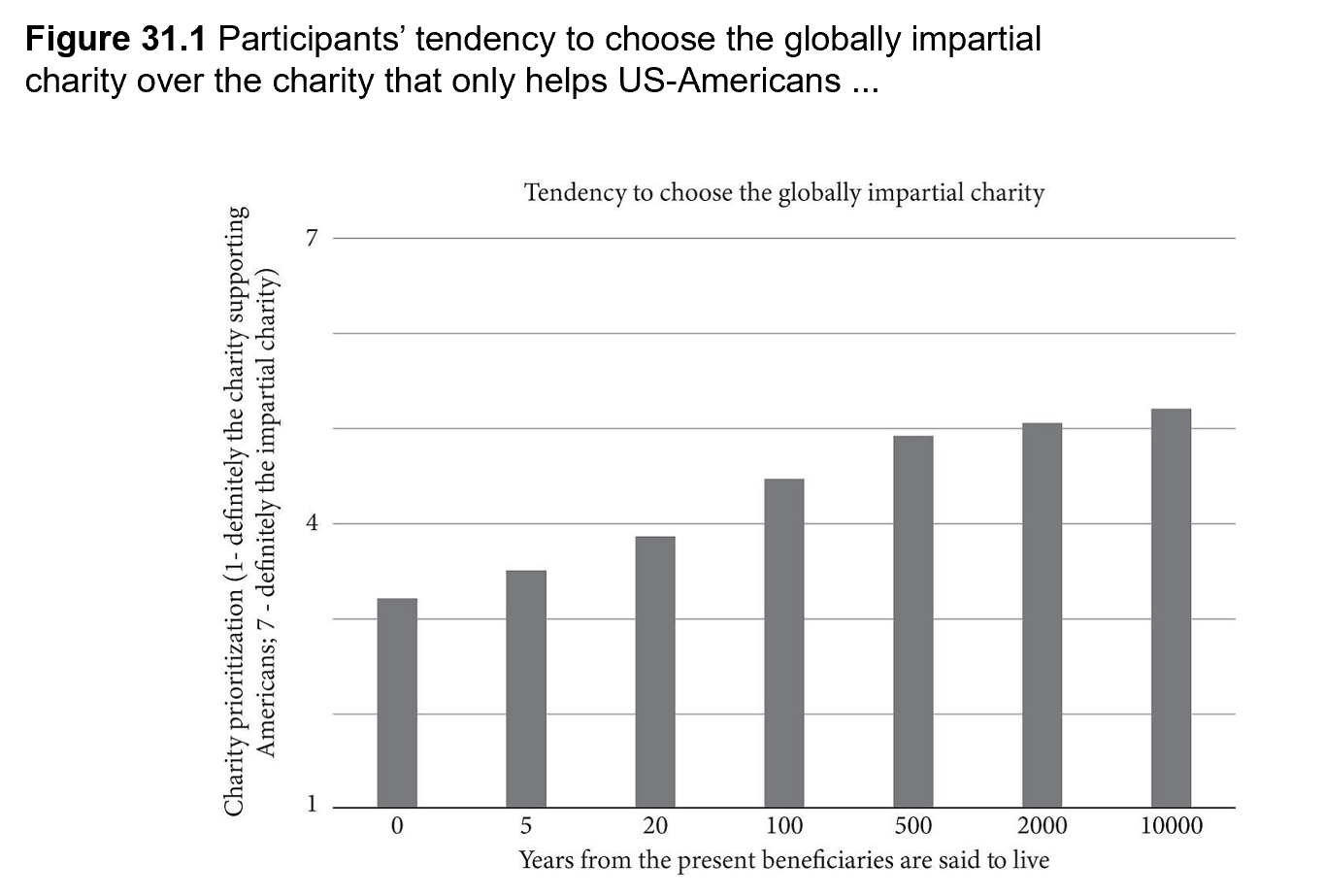

In our first study, we sought to answer that question. We asked American participants whether they would prioritise the national or the global charity, and varied the time at which the beneficiaries were said to live. We found a clear pattern: greater temporal distance meant a stronger tendency to prioritise the global charity.

As we will see, we believe that these results are driven by people’s moral judgements. There is, however, an alternative explanation: that people simply hold the empirical belief that their country won’t exist in the future. In Study 2, we tested this explanation by asking a subset of participants to assume that their country (the US) would still exist 5 or 500 years from now (with the year varying by condition). We found that these participants, too, were less likely to prioritise their compatriots when the beneficiaries lived further into the future. While the assumption reduced the effect somewhat, it persisted – meaning it’s unlikely to be driven by empirical beliefs alone.

Study 3 sought to generalise the findings of Studies 1 and 2 to other forms of partiality besides that for compatriots. We found that temporal distance also weakens people’s inclination to prioritise their local community and their own family and its descendants. These findings further entrench the findings from the previous studies.

Finally, in Study 4, we turned to another potential connection between our two psychological dimensions, relating to individual differences. Are people who are more likely to prioritise their compatriots over foreigners also more likely to prioritise current people over future people? We found that the answer is yes. This result is in line with other research that has found that different types of moral partiality (e.g. racism and speciesism) are psychologically related.

Why is it that temporal distance reduces ingroup favouritism? One way to think about it is in terms of relative differences. In the present, people strongly prefer their compatriots over foreigners. But when we shift attention to the distant future, everyone feels far away, reducing the gap between compatriot and foreigner. The added distance makes national boundaries seem less significant compared to the temporal gulf separating us from all future people.

This raises a further question. If people adopted a more longtermist perspective – if they became more focused on the interests of future beneficiaries – would they thereby become more cosmopolitan? Could longtermism bring the world together? Our findings cannot establish this with certainty, but they suggest it is a possibility. It’s certainly a question that deserves further study. If these results hold up, they would entail that cosmopolitans have instrumental reasons to promote long-term thinking, over and above intrinsic reasons for doing so.