A Moral Parliament Tool for Distributing Resources across Farmed Animal Recipients

By Hayley Clatterbuck @ 2025-10-15T20:27 (+26)

Executive Summary

- Our Moral Parliament Tool allows users to navigate normative, metanormative, and empirical uncertainty. It does so by representing diverse worldviews as delegates in a democratic decision-making process about how to distribute resources to various causes or projects.

- We have added functionality to the original Parliament Tool, which allows it to be adapted to novel resource allocation problems. In this sequence, we demonstrate the versatility and utility of the tool by applying it to analyze various types of problems.

- Here, we present a parliament to set funding priorities across different kinds of farmed animals: chickens, fish, shrimp, and insects.

Introduction

In this sequence, we explore how RP’s Moral Parliament Tool can be adapted to support deliberations about a range of resource allocation problems. The original version of the Parliament allows users to compare particular animal welfare projects. Here, we consider how it can be used to address a more general resource allocation question: how much money should be devoted to helping different kinds of animals? We will consider a philanthropic organization that is deciding on strategic priorities among efforts to help farmed chickens, fish, shrimp, or insects. Once it has set these priorities, it can then evaluate specific charitable projects that target each one.

We will consider three factors relevant to this priority setting. The first is the scale: how many individual animals would be affected per dollar of investment? The second risk tolerance: how willing should we be to make investments that might do little or no good? The third is moral weight: how much relative weight should we give to outcomes that affect different kinds of animals? The Parliament illustrates how different answers to these questions will yield different recommendations and how individuals with different views could decide how much to allocate to each group of animals.

Why use the Moral Parliament Tool to answer these questions, as opposed to a cost-effectiveness analysis? Some of the functions the Tool performs are very similar to a CAE, in that you can see how changing assumptions yields changes to a worldview’s assessment of a project. An additional benefit of the Tool is that it yields comparisons across projects. For example, if you change a worldview’s risk aversion, you can see how this changes its assessment of all projects under consideration (rather than having to do separate CAEs for each). The most important unique function of the Tool is that it allows you to aggregate the assessments of different worldviews or assumptions to see what you should do in light of that uncertainty. It’s one thing to know how different participants assess the options. It’s another thing to know what to do when they disagree.

Animal moral weights and projects

Scale

We determined the scale of projects by estimating the number of animals affected by top-level charities per $1 million invested. When the range of estimates was wide, we chose roughly the mean estimate. Please note that if you believe these estimates are inaccurate, you can modify them in the web-based tool. We used the following default scale values:

Chickens: 50 million (sources 1, 2, 3, 4)

Fish: 5 million (sources 1, 2)

Shrimp: 1.5 billion (source 1, 2)

Insects: 1 billion (source 1, 2)

Risk

Worldviews that are risk-averse place less weight on (i.e., they discount) positive outcomes, thereby placing more weight on the worst-case scenarios that could happen. To specify the risk profile of a project (here, money devoted to a type of animal), we estimate the probability that it will result in 0x, 1x, or 10x the estimated scale.[1] That is, will the project help 0 animals, the number of animals in the scale estimate, or 10 times as many animals as estimated? Here, the risk profile is a function of two factors: chance of project success and probability of sentience.

First, we estimate the variance in possible concrete effects of projects in that space. For example, the insect welfare space is relatively new, with few established projects, resulting in a high variance in possible effects. It’s not that unlikely that an insect project could benefit 1% of farmed insects, in which case it would help 10x the estimated scale number. There is also a good chance that insect projects will fail, as best practices in that field are still in development. The best chicken welfare projects are comparatively well-understood and established, resulting in lower variance.

Second, if we devote resources to a kind of animal that turns out not to be a welfare subject at all, then those projects will end up helping 0 animals. Therefore, the chance of the project being unsuccessful must also take into account the probability of sentience. For example, suppose we estimate a 35% chance that affected insect species are sentient. In that case, this contributes to an additional 65% chance that the project yields no effects (on top of the existing chances of project failure, even if they are sentient).

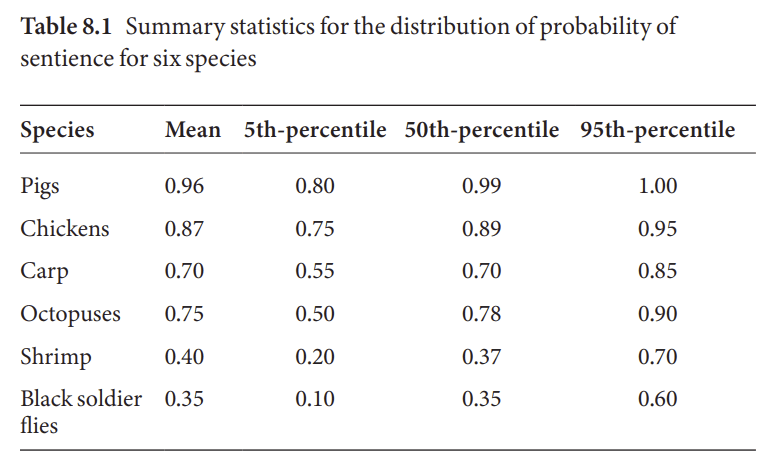

We used the mean estimates of the probability of sentience from Fischer, et al. (2024, 224):[2]

Moral weights

Finally, different worldviews will place different moral weights on the animals under comparison. We include two different sets of worldviews. First, we used RP’s mean welfare ranges. These were not weighted by the probability of sentience, since that was already accounted for in the risk dimension. Second, we used RP’s estimated welfare ranges based purely on neurophysiological proxies (such as neuron count), which give much lower estimates of welfare ranges (ibid.):

| Animal Type | RP welfare range | Neuro welfare range |

| Chickens | 0.46 | 0.037 |

| Fish | 0.34 | 0.00084 |

| Shrimp | 0.2 | 0.00088 |

| Insects | 0.2 | 0.00057 |

Selected Results

Project scores by worldview

The resulting Parliament can be found here (spreadsheet here).

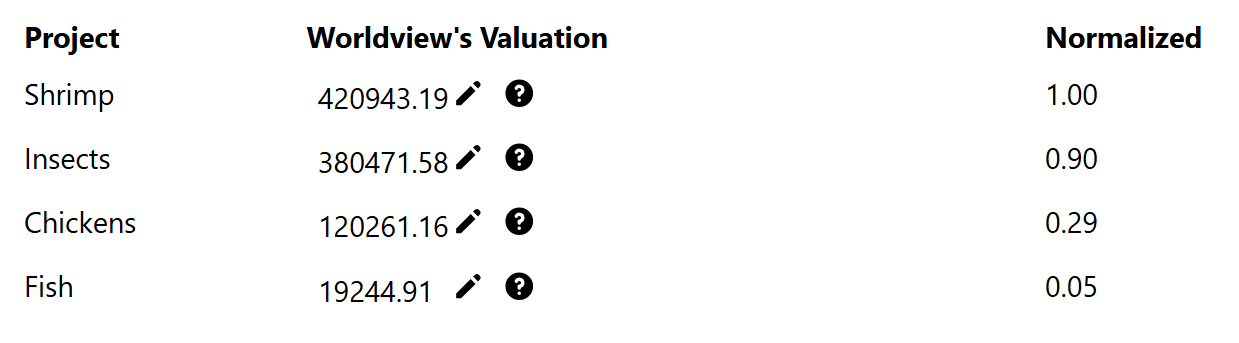

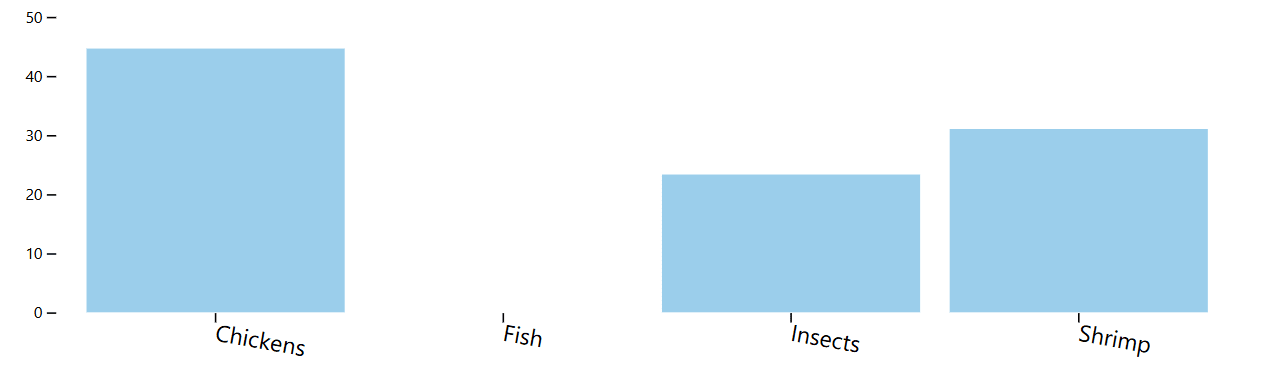

Worldviews that use RP’s welfare ranges favor shrimp and insects by a wide margin. This is especially the case if they are risk neutral, but holds even when highly risk averse:

Project scores for the RP Moral Weights, Strong Risk Aversion worldview.

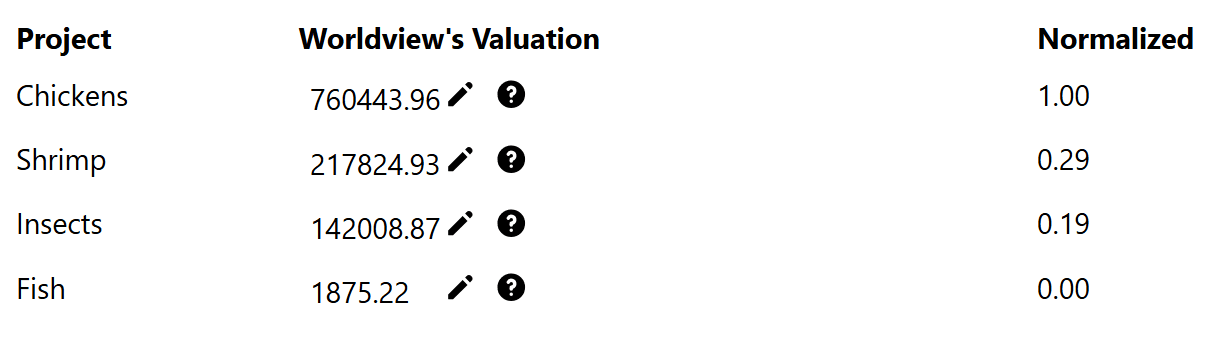

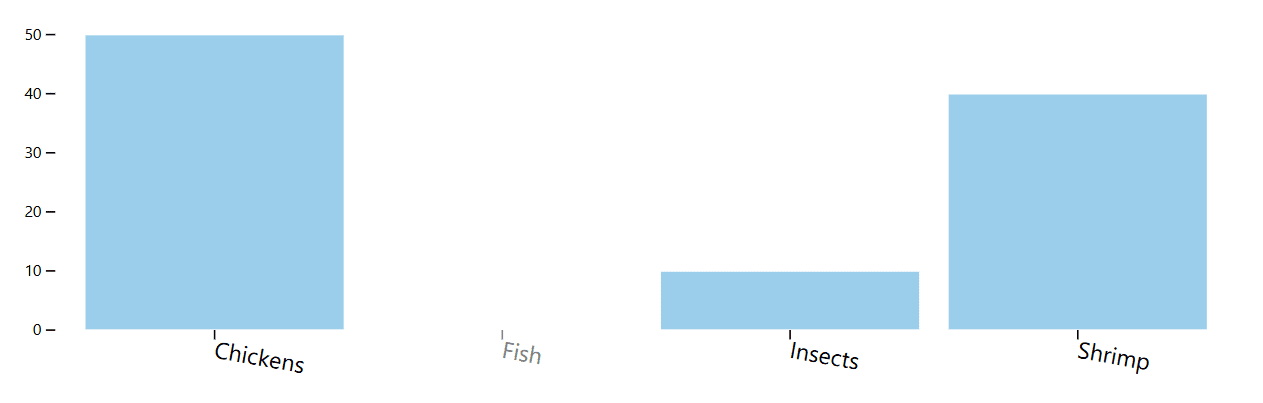

In contrast, worldviews that use the neurophysiological welfare ranges favor chickens by a wide margin. The results are quite robust across all levels of risk aversion:

Project scores for Neurophysiological Moral Weights, Moderate Risk Aversion worldview.

Results of deliberation

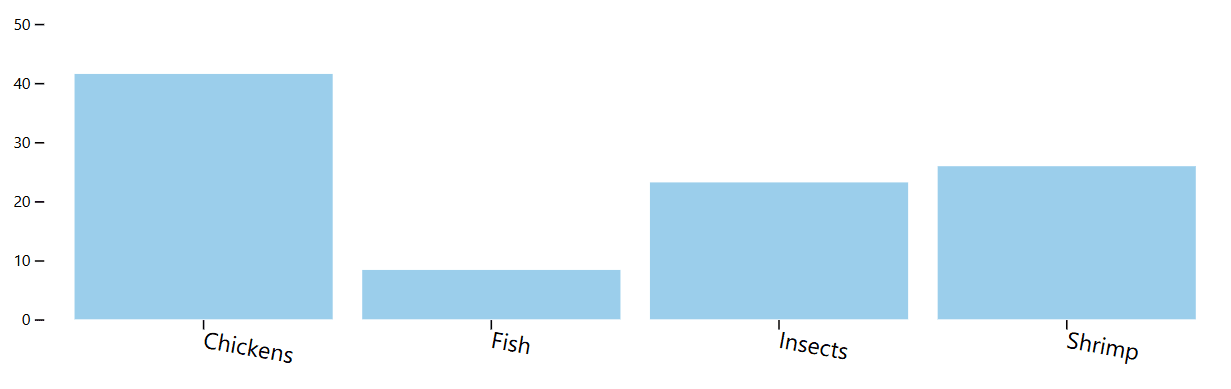

If we populate the parliament with an equal number of delegates for each worldview, most methods recommend fairly diverse allocations across animal types. If we use Moral Marketplace, giving each worldview a share of the budget to spend how it sees fit (and assuming diminishing returns), we get the following allocation:

Results of Moral Marketplace with equal representation of worldviews.

If we allow the worldviews to bargain from this starting position, the worldviews are willing to trade the portion of the budget going to fish to give to the other three buckets:

Results of Nash bargaining with equal representation of worldviews.

Approval voting gives similar results:

Results of approval voting with equal representation of worldviews.

Other allocation methods yield different results. Maximin recommends giving everything to chickens. If we use a Borda vote or ranked choice voting to select a single recipient category, shrimp is the winner.

Conclusion

We intend the examples in this sequence as a proof of concept that the basic framework of the Parliament Tool can be applied to a diverse array of problems. We do not intend them as the final say in modeling these domains. We have made important and contentious assumptions about key parameters in the model, including the probabilities of sentience, project magnitudes, and welfare ranges. We invite users to explore alternatives to these assumptions by constructing their own worldviews and setting their own project estimates.

If you would like assistance in setting up a custom Parliament application for your organization or to make allocation decisions, please contact us.

Acknowledgments

The Moral Parliament Tool is a project of the Worldview Investigation Team at Rethink Priorities. Arvo Muñoz Morán and Derek Shiller developed the tool; Hayley Clatterbuck created the particular parliaments in this sequence. We’d like to thank David Moss and Urszula Zarosa for helpful feedback. If you like our work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can explore our completed public work here.