Ambition (Effective Altruism Definitions Series)

By ozymandias @ 2025-08-14T00:17 (+17)

One of the most distinctive features of effective altruism is that it requires you to do shit. Effective altruists are constantly donating money, starting nonprofits, donating kidneys, creating conspiracies to infiltrate the highest levels of the U.S. government, etc.

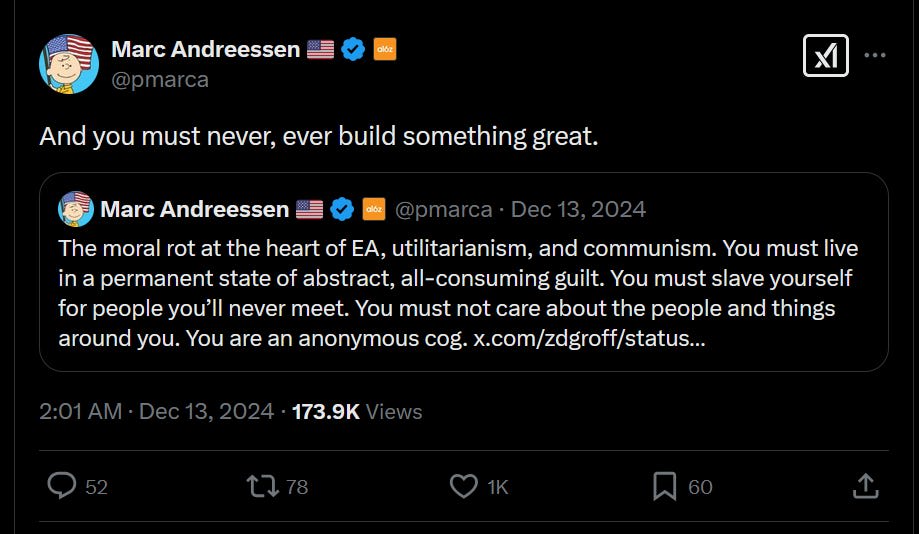

Normally, I see new effective altruists and people who aren’t effective altruists talk about this fact using the language of “guilt” and “moral obligation.” Not donating to effective charities is basically murder, so if you buy a cookie you’re evil. You have to save the drowning child, or you’re a bad person. This shit—

I don’t like this because I don’t think people should be anonymous cog slaves all-consumed by abstract guilt. But, more to the point, the guilt/obligation framing doesn’t match to how any successful, high-achieving effective altruist I know seems to relate to their altruism.

I mulled over the title of this post for days trying to find a word in which to encapsulate the distinction, and finally settled on “ambition.”

We can all think of nonaltruistically ambitious people. Certainly Marc Andreessen does—he’s a venture capitalist. A founder who isn’t content until she has a unicorn startup, and then once it IPOs turns around and starts another one. A chess player trying to become a grandmaster—or a speedrunner trying to set a world record. A novelist who is constantly honing her craft. A lawyer who puts in hundred-hour weeks trying to make partner. A small business owner who plans to pass along her landscaping business to her children. A grad student who sacrifices her twenties to writing about the diets of tanners in 16th century Flanders.

But I think people feel strange about being altruistically ambitious. I think the objection is similar to people’s objection to doing the math about charity effectiveness. You’re supposed to help people in a soft-hearted, emotional way. Ambition is cold and ruthless. The altruism bucket is the Gryffindors, or maybe the Hufflepuffs. The ambitious bucket is Slytherins, and it’s full of evil racists!

The novelist or the startup founder, the grad student or the small business owner, never reach their goal. Your company can always be more successful; your novel, more beautiful; your research, less likely to provoke disdainful scoffing from time-traveling Flemish artisans. But that doesn’t mean that they’re always consumed with guilt or obligation, or that startup founders are sitting there going “if my company is only worth $50 million, I’m the equivalent of Hitler.”

Ambitious people, healthy ones, find high standards exhilarating. There is always another challenge to face, always somewhere higher to climb. If you go to a speedrunner and say “you know, lots of people take fifty hours to play this game and have a great time doing it, you don’t have to hold yourself to the standard of solving it in ten minutes,” the speedrunner would think you’re missing the point.

Ambitious people feel divine discontent:

To me, divine discontent is about cheerfully seeking out dissatisfaction. It’s choosing to ask, What could be better? What can I improve? It’s a feeling that practitioners across many fields—in literature, art, music, performance, film; but also the sciences, engineering, and mathematics—can relate to.

The author elaborates in an anecdote that made me groan with self-recognition:

- I’m preparing dinner at home with my girlfriend. I make the salad, improvising with whatever herbs we have in the refrigerator, and make the vinaigrette without measuring anything. She tries to recreate a pasta dish she tried at a restaurant once. We sit at the table and critique our efforts. The vinaigrette is too sharp, I tell her. Next time I’ll use a rounder, milder vinegar, or balance the acid out with some maple syrup. Meanwhile, she’s evaluating her dish and deciding that it needs better tomatoes, more salt, more tarragon.

There’s a difference, of course, between caring deeply about quality and being excessively critical! But this instinct to critique my own work, to understand what fell short and fix it—that’s the divine discontent. Personally, I find that it’s genuinely fun to live like this. It makes life interesting! It means there is always something to care about and be passionate about.

I have been known, after cooking for Friday night family dinner, to announce “it’s time to criticize the meal!”[1] Most effective altruists are more reasonable than me about the quality of their cooking. But I imagine a typical effective altruist going “I’m not really prioritizing improving my cooking right now, what with all the ongoing apocalypses.” And I imagine a normal person going “what the fuck? You’re a crazy person.”

Ambition and divine discontent is linked to a concept that effective altruists call “agency.” I like Neel Nanda’s post about agency, in which he defines the concept:

Our lives are full of constraints, and defaults that we blindly follow, going past this to find a better way of achieving our goals is hard.

And this is a massive tragedy, because agency is incredibly important. The world is full of wasted motion. Most things in both our lives and the world are inefficient and sub-optimal, and it often takes creativity, originality and effort to find better approaches. Just following default strategies can massively hold you back from achieving what you could achieve with better strategies.

Agency can mean:

- Taking personal responsibility for your actions and goals.

- Thinking strategically; having a plan to achieve your aims.

- Noticing greyed out options.

- Having an internal locus of control.

- Being willing to do weird things if they work.

- Experimenting with different approaches to a problem.

- Messing around, taking risks, trying new things; figuring that you can always fix things if they break.

- Failing, picking yourself back up, and doing something else.

- Feeling confidence all the way up.

- Thinking “will this action I’m taking accomplish anything I want, or will it make everything worse?” and then—very important—not doing it if it’s that second thing.

To put it another way, ambition is having the high goals; agency is being the sort of person who might achieve them.

Effective altruists are, I think, careful not to push ambition on everyone. I have been present in a number of conversations where people loudly agree with each other that not all programmers need to be technical AI safety researchers and if you just want to make Facebook Messenger 0.0001% faster that is valid. But the presence of the divinely discontented tends to shift the standards for everyone: they have tricked a number of normal people into thinking that donating nearly six times as much as the average American is the ordinary standard that normal people ought to be holding themselves to. Not in a way where you’re consumed by guilt if you don’t, of course, any more than people who aren’t effective altruists are consumed by guilt if they forget to return a shopping cart or claim to their child that the Leapfrog Phonics Bus’s batteries died and can’t be replaced because doing so was banned by the Geneva Convention.

I see effective altruists saying “oh, I’m not doing anything big, although of course I donate my ten percent” and I want to shake them and go THAT IS BIG! DONATING TEN PERCENT OF YOUR INCOME IS A BIG THING! YOU ARE AT NEGATIVE SIX KILLS AND COUNTING!

But that’s the secret. You don’t have to do anything particularly special to be agentic and ambitious. No matter how good or bad you are, whether you are Gandhi or Hitler, you can always be better tomorrow than you were today.

Ambition and agency aren’t a stick you can beat yourself with because you’re a failure. They aren’t an obligation at all, really. They’re an invitation.

The point is not to achieve some particular standard. The point is not to be better than average (or six times better, specifically). The point is—to quote a certain venture capitalist I know—to build something great.

If you’ve gone as far as you want to, you can sit and rest. If you want to keep going, the path awaits you.

This is, then, the final principle of effective altruism, as I see it: You can do hard things. Not that you have to do hard things; not that you are a bad person who ought to hate yourself if you don’t do hard things; just that you can do hard things, if you want to.

In the next three posts in the series, I’ll discuss the approach of effective altruists to three specific areas: cause evaluation, history, and politics.

- ^

The effective altruist culture of criticism is fascinating but I think belongs in its own post.

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-14T20:12 (+2)

Executive summary: This post argues that the heart of effective altruism is not guilt-driven obligation but “altruistic ambition” — a mindset of agency and “divine discontent” that frames doing good as an open-ended, energizing challenge to build something great, rather than a burdensome moral duty.

Key points:

- Critics like Marc Andreessen frame EA as joyless self-sacrifice, but the author contends successful EAs are motivated by ambition, not guilt.

- “Altruistic ambition” parallels non-altruistic ambition — an ongoing pursuit of excellence and improvement without being consumed by failure.

- The concept of “divine discontent” captures the drive to continually ask “what can be better?” and find satisfaction in striving, not just achieving.

- Ambition is paired with “agency” — the willingness and creativity to act strategically, deviate from defaults, and take personal responsibility for outcomes.

- EA culture can raise collective standards (e.g., donating 10% of income) without turning them into moral cudgels; such actions remain significant achievements.

- The invitation of EA is not that you must do hard things, but that you can — an open path for those who want to keep building and improving.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Kevin Xia 🔸 @ 2025-08-23T11:42 (+1)

Just wanted to drop by and say that I have been really enjoying this sequence, and I deeply resonate with this idea of divine discontent!

idea21 @ 2025-08-14T12:52 (+1)

I don’t think people should be anonymous cog slaves all-consumed by abstract guilt.

Ethical motivation is the key to moral progress. Feeling guilty for not acting correctly, feeling ashamed (before whom?) for not avoiding evil.

Is it deontology? Stoic ethics was largely based on this.

From a utilitarian point of view, any motivation is good as long as it produces the greatest good for the greatest number.

The problem is that the motivation system currently established by the EA community doesn't seem to be effective enough. And it's completely contrary to the cost-benefit principle not to explore other options.

Matrice Jacobine @ 2025-08-14T14:08 (+2)

I've known EAs who have been all-consumed by abstract guilt. It has never led them to producing the greatest good for the greatest number. At best it led them to being chronically depressed and unable to do any stable work. At worst it has led to highly net negative actions like joining a cult.